Abstract

Canine circovirus (canine CV) is an etiological agent associated with diarrhea, hemorrhagic gastroenteritis and vasculitis. Although canine CV has been identified and characterized in southern China in recent years, its epidemiology in other regions of China and its precise molecular characteristics have not been examined. In this study, we examined 141 fecal specimens collected from domestic dogs with or without diarrhea in Heilongjiang province, Northeastern China, during 2014 to 2016. A total of 18 out of 141 samples were found to be positive for canine CV by real-time quantitative PCR. In the diarrhea samples, canine CV was detected in coinfections with canine parvovirus 2. More importantly, two different canine CV strains were detected in one sample. Five canine CV genomes were successfully amplified. Sequence analysis showed that there were two unique amino acid changes in the Rep protein (N39S in the K1 strain, and T71A in the XF16 strain). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that canine CV could be divided into four genotypes, and specific nucleotide mutations could be used for confirming the four genotypes. Moreover, recombination analysis revealed that a total of eight recombination events were found in five genomic sequences. Molecular evolution analysis showed that the canine CV has been under purifying selection. This study provides evidence that at least three genotypes of canine CV are co-circulating in China. Continuous epidemiological surveillance is therefore necessary to understand their importance for the evolution of canine CV.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00705-019-04433-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Circoviruses are small, non-enveloped, spherical viruses that are about 20 nm in diameter and possess a circular, single-stranded DNA genome of approximately 2 kb, in size [1]. The family Circoviridae is divided into two genera: Circovirus and Cyclovirus. Circoviruses have two main inversely arranged ORFs encoding the replicase protein and capsid protein, respectively [2, 3]. Circoviruses have been identified in a number of birds and other animals as well as humans. While some circoviruses cause subclinical infections, others can cause serious diseases with a serious economic impact [4], such as porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2), which affects pigs all over the world [5]. Circoviruses have been confirmed to be associated with vesicular and hemorrhagic and enteric diseases as well as low body weight, poor body condition, and feathering disorders in birds [6, 7]. An immunosuppressive effect has been observed in infections with PCV2, psittacine beak and feather disease virus, pigeon circovirus, and duck circovirus [8, 9].

Canine circovirus (canine CV) was first detected in serum samples from dogs in the United States in 2012 [2]. Canine CV has been reported to be associated with vasculitis, hemorrhage, hemorrhagic enteritis, and diarrhea [10–13]. Canine CV DNA has also been discovered in mesenteric lymph nodes and ileal Peyer’s patches in infected dogs [3, 10]. Furthermore, canine CV may act as a coinfection factor and play a role in the development of disease [14, 15]. In addition to dogs, canine CV has also been detected in wolves and badgers [16]. However, the pathogenicity of canine CV is still controversial. Moreover, little is known about the evolutionary dynamics and genetic variation of this virus. Recently, the prevalence and genetic variation of canine CV in Guangxi, Southwest China, have been reported, but the epidemiology of this virus in other regions of China is still unclear.

In the present study, we collected 141 fecal samples from dogs in Heilongjiang Province, Northeast China, tested them for the presence of canine CV by real-time quantitative PCR, and cloned the complete genome of individual isolates. In addition, genetic variation, polymorphism analysis, and recombination analysis were undertaken, and genotyping based on all known canine CV strains was done using phylogenetic analysis.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

A collection of 141 fecal samples was obtained from domestic dogs in Heilongjiang province, Northeast China, from April 2014 to February 2016. Of these, 96 dogs had diarrhea, and 45 were healthy without clinical symptoms. In the healthy dogs, 21 out of 45 had a history of diarrhea in the past half year, 10 did not have a history of diarrhea, and the status of the others was unknown. Fecal samples were gathered by inserting a swab 2 cm into the rectum. The samples were stored at -20 °C until further handling.

Laboratory investigation

The fecal samples were examined for common pathogens. For detection of bacterial pathogens, the samples were inoculated onto 5% sheep blood agar (Biocell BioTech., Co., Zhengzhou, China) and cultured at 37 °C for 48 h under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Subsequently, bacterial identification was carried out using a Biolog Microbial ID System (GeneIII, Biolog Inc. USA). Meanwhile, the fecal samples were examined for common enteric viral pathogens. DNA and RNA were extracted from each fecal sample using a Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Axygen, Corning Incorporated) or TRIzol LS (Gibco-BRL, Life Tech.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR and RT-PCR assays were used for detection of canine coronavirus, canine parvovirus type 2 (CPV-2), canine distemper virus, rotaviruses, caliciviruses, and astroviruses. Real-time PCR for the detection of canine CV was conducted as described by Hsu et al. [12]. The feces were also examined for intestinal parasites using zinc sulfate flotation.

Amplification, cloning, and full-genome sequencing of canine CV from positive samples

To amplify the complete genome of canine CV from the positive samples, PCR was carried out using KOD FX Neo DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Japan) and four pairs of PCR primers (Table S1). The PCR products were purified using a DNA Purification Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing) and were ligated into the pMD19-T simple vector (TaKaRa Biotech, Dalian, China). Then, the recombinant plasmids were sequenced by Comate BioTech (Changchun) Co., Ltd.

Sequence analysis, polymorphism analysis, and recombination analysis

Nucleotide sequences were analyzed using the programs in the DNAStar software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). The genomic sequences obtained in this study, together with all the available complete genome sequences in the GenBank database (Table S2), were aligned by the Clustal W method. A phylogenetic tree based on the main ORFs (ORF1 plus ORF2) was constructed by the neighbor-joining method in MEGA7 [17], using the aligned data set, and statistical support was evaluated using 1000 bootstrap replicates.

DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of complete genome sequences was carried out using DnaSP ver. 5.10.00 [18]. To examine the neutral theory of evolution, Fu and Li’s D and F [19] tests were used, and the rates of non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) mutations were calculated using DnaSP ver. 5.10.00.

Recombination events in the canine CV strains were detected using the Recombination Detection Program package, which includes the RDP, GENECONV, Maxchi, Chimaera, 3Seq, Bootscan and SiSscan programs (RDP4) [20] to identify putative recombination sites in the among aligned DNA sequences. Recombination events were considered likely only if they were detected by at least four of the seven programs in the package with a P-value ≤ 0.01.

Results

Detection of canine CV as a causative agent of enteritis

In the present study, real-time PCR results showed that 12.8% (18/141) of the samples tested were positive for canine CV (Table 1). In diarrhea samples, 15 out of 96 (15.6%) were identified as canine CV positive, and all of the 15 positive samples were coinfected with CPV-2 and/or other pathogens. About 40% (6/15) of the positive samples had two different pathogens, canine CV and CPV-2; 46.7% (7/15) had a triple infection, and 13.3% (2/15) had a quadruple infection. Correspondingly, in the healthy group, the results showed that three out of 45 samples (6.7%) were positive for canine CV. Two of the dogs that were positive for canine CV were among the 21 that had a history of diarrhea in the preceding half year (9.5%). In the samples from dogs without a history of diarrhea, none were positive for canine CV (0/10). Of the 14 samples from dogs with uncertain history of diarrhea in the preceding six months, only one was positive for canine CV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Canine pathogens detected in the samples

| Sample name | Location | Sampling month | Age (months) | Fecal condition | DogCV | Other enteric pathogens detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Daqing | April/2014 | 46 | Diarrhea | + | CPV+ETEC+Salmonella |

| 2 | Daqing | April/2014 | 2 | Diarrhea | + | CPV+ETEC |

| 3 | Daqing | May/2014 | 17 | Diarrhea | + | CPV |

| 4 | Daqing | November/2014 | 35 | Diarrhea | + | CPV |

| 5 | Qiqihar | November/2014 | 120 | Diarrhea | + | CPV |

| 6 | Daqing | November/2014 | 18 | Diarrhea | + | CPV+caliciviruses |

| 7 | Daqing | February/2015 | 9 | Diarrhea | + | CPV |

| 8 | Mudanjiang | February/2015 | 3 | Diarrhea | + | CPV+ETEC |

| 9 | Mudanjiang | June/2015 | 14 | Diarrhea | + | CPV+ETEC |

| 10 | Harbin | June/2015 | 28 | Diarrhea | + | CPV+ETEC |

| 11 | Mudanjiang | June/2015 | 48 | Diarrhea | + | CPV+caliciviruses |

| 12 | Qiqihar | June/2015 | 5 | Diarrhea | + | CPV+ETEC |

| 13 | Mudanjiang | November/2015 | 10 | Diarrhea | + | CPV+ETEC+STEC |

| 14 | Harbin | November/2015 | 52 | Diarrhea | + | CPV |

| 15 | Harbin | November/2015 | 13 | Diarrhea | + | CPV |

| 16 | Harbin | February /2016 | 28 | Healthy(Diarrheic in recent half a year) | + | _ |

| 17 | Harbin | February /2016 | 33 | Healthy(Diarrheic in recent half a year) | + | _ |

| 18 | Harbin | February /2016 | 84 | Healthy(Unknown situation in recent half a year) | + | _ |

There was a significant difference in the rate of detection of canine CV between the diarrheic group and the healthy group (P = 0.009); however, there was no significant difference between samples from dogs with diarrhea history and those without a history of diarrhea in the healthy group (P > 0.05).

Full-genomic characterization of the canine CV strain

Although 18 positive samples were detected, unfortunately, only five complete genome sequences were obtained, namely, those of canine CV isolates XF16, K1, C79, C24 and C85 (GenBank ID MF797786, MK731982, MK944079, MK731981 and MK944080). It should be noted that the isolates C79 and C24 were obtained from the same positive sample. Similar to other canine CV isolates, the length of the genome of the new strains was 2,063 nt.

The sequence identity among the complete genomic sequences of canine CVs in this study ranged from 98.7% (strain C24 vs. C85) to 93.2% (strains C24 and C85 vs. XF16). A comparison using just the replicase sequences revealed identities of 92.1-98.6% at the nt level and 95.7-98.7% at the aa level. A comparison of capsid sequences showed 93.7-98.9% identity at the nt level and 95.9-98.7% at the aa level.

A comparison of the five sequences in this study with published sequences in the GenBank database revealed overall sequence identities of 85.2-96%. Comparisons of the replicase sequences and capsid sequences with published sequences in the GenBank database showed that the replicase sequences had 84.5-98.7% nt sequence identity and 90.5-98.7% aa sequence identity, and the capsid sequences showed identities of 80.7-97.3% and 91.1-98.5-% at the nt and aa level, respectively. In the replicase protein, there were two amino acid changes that were unique to strain K1 (N39S) and strain XF16 (T71A).

Phylogeny analysis

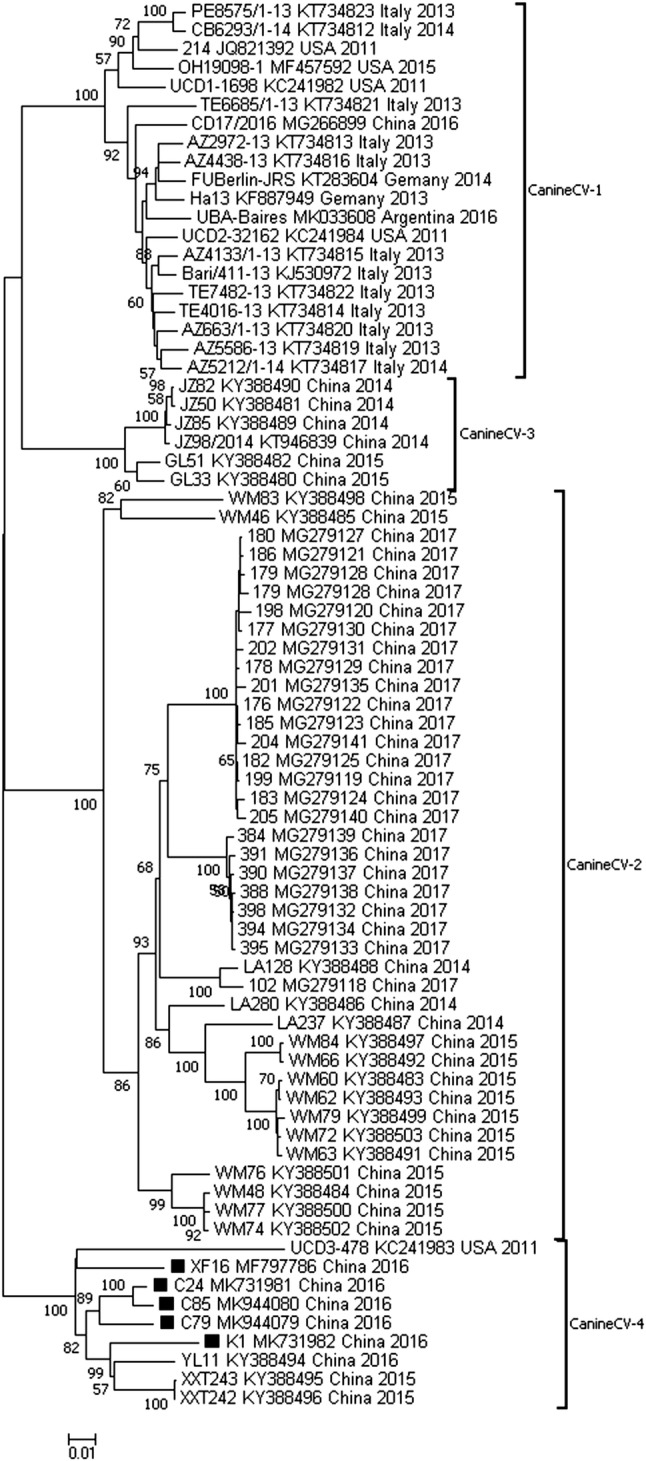

A phylogenetic tree based on the combined ORF1 and ORF2 nucleotide sequences available in the GenBank database (n = 75), is shown in Fig. 1. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the 75 genes of global canine CV strains were segregated into four distinct groups with strong (100%) bootstrap support, namely, canine CV 1, canine CV 2, canine CV 3 and canine CV 4. The canine CV 1 group consisted of 12 strains from Italy, two from Germany, one from Argentina, one from China and four from the USA, including the first canine CV strain that was discovered (JQ821392). The canine CV 2 group consisted of most of the Chinese strains investigated as well as three strains that were detected in the year 2014, 13 strains from 2015 and 24 strains from 2017. The canine CV 3 group included six strains from China detected in the years 2014 and 2015. The other nine strains, including the USA UCD3-478 strain (KC241983), belonged to the canine CV 4 group, which included five strains from this study and three strains isolated from Guangxi Province, China, in 2015–2016.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of canine circovirus. Neighbor-joining trees based on the combined ORF1 and ORF2 regions. The reference strains and GenBank accession numbers are listed in Table S2. Statistical support was provided by bootstrapping with 1,000 replicates. The scale bars indicate the estimated numbers of nucleotide or amino acid substitutions. Filled squares indicate strains that were first mentioned in this article

Some individual nucleotide sequence polymorphisms could be used for differentiating the four genotypes. The nucleotide substitutions specific to the genotype canine CV 2 were mainly localized at positions 525 (G to T), 579 (G to A), 1066 (A to G), 1219 (T to A), 1258 (A to G), 1281 (T to A), 1489 (G to T), 1509 (G to A), 1513 (G to A), 1558 (C to A), 1638 (A to T) and 1639 (T to C). The nucleotide variations at six positions 891 (C to T), 961 (T to A), 970 (G to A), 1021 (C to T), 1129 (A to G) and 1192 (A to T) were unique for the genotype canine CV 3. Finally, five positions, 1212 (T to G), 1213 (T to C), 1219 (T to C), 1372 (T to G) and 1435 (G to A) contained variations that were unique to the genotype canine CV 4.

A neighbor-joining tree constructed based on the complete genome, replicase protein gene and capsid protein gene are shown in Fig. S1.

Polymorphism analysis

DNA sequences were compared to evaluate the genetic diversity of canine CV, and the average number of pairwise nucleotide differences (K) was 211.881. The nucleotide sequence diversity (π) was 0.10275, and the overall haplotype diversity (Hd) for the 75 canine CV sequences was 1.000 ± 0.002. The highest peak of nucleotide sequence diversity was within the region of nucleotide positions 301-400, whereas the most conserved region was within the region of nucleotide positions 901–1050. Of the 734 polymorphic sites, 239 were singleton variable sites and 496 were parsimony-informative sites. Te Fu and Li’s D and F values for canine CV were also negative: -0.32754 (P > 0.10) and -0.20165 (P > 0.10), respectively. The rate of non-synonymous (Ka) to synonymous mutations (Ks) was estimated. Ka (0.05637) was found to be lower than Ks (0.32477) and the Ka/Ks ratio was 0.17357, indicating that canine CV is spreading within the population and/or is under purifying selection pressure.

Recombination analysis

Eight potential recombination events were discovered in the five sequences in this study by seven methods (RDP, GENECONV, BootScan, MaxChi, Chimaera, SiScan, 3Seq) in RDP4. As shown in Table 2, two putative recombination sites were found in each of the isolates XF16, C24 and C85, and one was found in each of the isolates K1 and C79. The reliability of these results is supported by p-values less than 0.01 for at least four of the seven methods used.

Table 2.

Putative recombination events amongst the five canine CV genomes sequenced, detected by the RDP, GeneConv, BootScan, MaxChi, Chimaera, SiScan and 3SEQ algorithms

| Event number | Strain | Major parent | Minor parent | Position(in alignment) | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDP | GENECONV | BootScan | MaxChi | Chimaera | SiScan | 3SEQ | |||||

| 1 | C79 | 102 | FUBerlin-JRS | 1205–1690 | 4.470×10−5 | 2.197×10−4 | 1.858×10−4 | 3.377×10−5 | 3.748×10−5 | 4.850×10−6 | 1.337×10−6 |

| 2 | C24 | 102 | FUBerlin-JRS | 1205–1690 | 4.470×10−5 | 2.197×10−4 | 1.858×10−4 | 3.377×10−5 | 3.748×10−5 | 4.850×10−6 | 1.337×10−6 |

| 3 | C24 | GL33 | C79 | 60–1828 | 7.662×10−4 | 9.737×10−3 | 1.909×10−3 | 2.200×10−8 | - | 8.831×10−27 | 4.794×10−24 |

| 4 | K1 | 102 | FUBerlin-JRS | 1206–1598 | 4.470×10−5 | 2.197×10−4 | 1.858×10−4 | 3.377×10−5 | 3.748×10−5 | 4.850×10−6 | 1.337×10−6 |

| 5 | C85 | 102 | FUBerlin-JRS | 1205–1690 | 4.470×10−5 | 2.197×10−4 | 1.858×10−4 | 3.377×10−5 | 3.748×10−5 | 4.850×10−6 | 1.337×10−6 |

| 6 | C85 | GL33 | C79 | 100–1750 | 7.662×10−4 | 9.737×10−3 | 1.909×10−3 | 2.200×10−8 | – | 8.831×10−27 | 4.794×10−24 |

| 7 | XF16 | CB6293/1-14 | YL11 | 974–1860 | 7.885×10−14 | 2.183×10−11 | 3.158×10−12 | 8.700×10−14 | 2.571×10−9 | 1.365×10−23 | 1.199×10−35 |

| 8 | XF16 | UCD1-1698 | WM46 | 114–659 | – | 1.697×10−9 | 1.136×10−11 | 3.648×10−10 | – | 7.725×10−17 | 1.670×10−25 |

The sites of event 1 in isolate C24 and event 2 in strain C79, which were detected by all the seven algorithms, are located between nt 1205 and 1690, with strain 102 and FUBerlin-JRS as the major and minor parent, respectively. The site of event 3 in strain C24, which was detected by all methods except Chimaera, is located between nt 60 and 1828, with strain GL33 as the major parent. The site of event 4 in strain K1, which was detected by all methods, is located between nt 1206 and 1598, with strain 102 as the major parent. The sites of events 5 and 6 in strain C85 are located at nucleotide positions 1205-1690 and 100-1750, respectively, with strains 102 and GL33 as the respective major parents. In XF16, two sites of recombination events were identified, one from nt 974 to 1860 for event 7, with CB6293/1-14 as the major parent, and the other from nt 114 to 695 for event 8, with UCD1-1698 as the major parent. Most of the putative recombination events occurred within or close to the coding regions for the cap and rep proteins; one was located near the rep gene (Table 2, event 8), and five were located near the cap gene (Table 2, events 1, 2, 4, 5, and 7).

Discussions

In this study, for the first time, the prevalence of canine CV in northeastern China was investigated. The overall prevalence was found to be 12.8%, which was somewhat higher than the rate in Guangxi (8.75%, 81/926) but lower than the rate in Taiwan (28.02%, 58/207) [12, 21]. These differences might have been due to differences in sample types and geographic distribution. Our results indicated that the prevalence of canine CV among diarrheic dogs was 15.6%, while it was 6.7% among clinically healthy dogs. There were significant statistical differences between the two types of samples, as was also found in a study conducted in Taiwan [12], showing that the prevalence of canine CV in diarrheal dogs was significantly higher than that in healthy dogs (P < 0.001). However, this was inconsistent with a study in the USA that showed that the difference in prevalence between healthy dogs and diarrheic dogs was not significant [3].

At the same time, we also surveyed common pathogens in canine CV-positive samples and found that the most prevalent pathogen involved in coinfections with canine CV was CPV-2, which is consistent with the results of previous studies in Taiwan [12] and Italy [15].

Interestingly, we detected two different canine CV strains in one sample. Whether coinfection with different canine CV strains affects the pathogenesis and outcome of infection deserves further investigation.

Phylogenetic analysis based on the main coding sequences of the canine CV genome (ORF1 + ORF2), as was done previously with PCV3 [22], displayed clear clusters, providing evidence that canine CV can be divided into four genotypes. These results were supported by high bootstrap values and the presence of unique nucleotide mutations. Two of the four genotypes identified, canine CV 1 and canine CV 2 corresponded to groups identified previously by Sun et al. [21]. The groups canine CV 3 and canine CV 4, however, are newly emerging genotypes, which provides evidence that at least three genotypes of canine CV are co-circulating in China. Furthermore, these findings imply an association between genotypes and specific geographic locations. The genotypes canine CV 2 and canine CV 3 included all of the strains discovered in southwestern China, the genotype canine CV 4 mainly included strains from northeastern China, and all of the canine CV sequences that were not from China belonged to the genotype canine CV 1.

Using the RDP package, a total of eight recombination events were detected in the canine CV sequences in this study. Previous studies have shown that recombination events can occur not only in the replicase gene [23] but also in other parts of the genome [22], which is in agreement with our results. In addition, this study also confirmed that intra-genotypic and inter-genotypic recombination events have occurred. The major parent sequences that were identified were not only from China but also from abroad, suggesting that various strains have been prevalent in China.

In summary, we have investigated the prevalence of canine CV and coinfection of this virus with other enteropathogens in dogs in northeastern China. Two unique amino acid changes and new recombination events were found, and the virus was found to be under purifying selection. This study provides evidence that at least three genotypes of canine CV are co-circulating in China. However, our understanding of the pathogenic mechanism of this virus and its possible synergistic effects on other pathogens is still very limited. Continuous epidemiological surveillance is therefore necessary to understand the importance and evolution of canine CV.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the “Academic Backbone” Project of Northeast Agricultural University (No. 17XG10), State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Biotechnology Foundation (SKLVBF201611) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31672532). We would like to thank the owners who provided access to the animals examined in this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or live animals performed by any of the authors. Samples were collected only from animals for laboratory analyses, avoiding unnecessary pain and suffering of animals. The owners gave their written consent for sample collection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hongyan Chen, Email: chenhongyan@caas.cn.

Junwei Ge, Email: gejunwei@neau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Todd D, Mcnulty MS, Adair BM, Allan GM. Animal circoviruses. Adv Virus Res. 2001;57:1–70. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(01)57000-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amit K, Dubovi EJ, Jose Angel HR, Ian WL. Complete genome sequence of the first canine circovirus. J Virol. 2012;86:7018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00791-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linlin L, Sabrina MG, Kevin Z, Leutenegger CM, Marks SL, Steven K, Patricia G, Cruz FN, Dela CW, Eric D. Circovirus in tissues of dogs with vasculitis and hemorrhage. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:534–541. doi: 10.3201/eid1904.121390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alarcon P, Rushton J, Wieland B. Cost of post-weaning multi-systemic wasting syndrome and porcine circovirus type-2 subclinical infection in England—an economic disease model. Prevent Vet Medicine. 2013;110:88–102. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allan GM, Ellis JA. Porcine circoviruses: a review. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000;12:3–14. doi: 10.1177/104063870001200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fogell DJ, Martin RO, Groombridge JJ. Beak and feather disease virus in wild and captive parrots: an analysis of geographic and taxonomic distribution and methodological trends. Adv Virol. 2016;161:2059–2074. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2871-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hattermann K, Schmitt C, Soike D, Mankertz A. Cloning and sequencing of Duck circovirus (DuCV) Adv Virol. 2003;148:2471–2480. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0181-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X, Chen L, Yuan W, Li Y, Li L, Li T, Li H, Song Q. Effect of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) on the function of splenic CD11c+ dendritic cells in mice. Adv Virol. 2017;162:1289–1298. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todd D. Circoviruses: immunosuppressive threats to avian species: a review. Avian Pathol. 2000;29:373–394. doi: 10.1080/030794500750047126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, McGraw S, Zhu K, Leutenegger CM, Marks SL, Kubiski S, Gaffney P, Dela Cruz FN, Wang C, Delwart E, Gaffney P. Circovirus in tissues of dogs with vasculitis and hemorrhage. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:534–541. doi: 10.3201/eid1904.121390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decaro N, Martella V, Desario C, Lanave G, Circella E, Cavalli A, Elia G, Camero M, Buonavoglia C. Genomic characterization of a circovirus associated with fatal hemorrhagic enteritis in dog, Italy. PLos One. 2014;9:e105909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu HS, Lin TH, Wu HY, Lin LS, Chung CS, Chiou MT, Lin CN. High detection rate of dog circovirus in diarrheal dogs. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12:116. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0722-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson A, Hartmann K, Leutenegger CM, Proksch AL, Mueller RS, Unterer S. Role of canine circovirus in dogs with acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea. Vet Rec. 2017;180:542. doi: 10.1136/vr.103926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thaiwong T, Wise AG, Maes RK, Mullaney T, Kiupel M. Canine circovirus 1 (CaCV-1) and canine parvovirus 2 (CPV-2): recurrent dual infections in a papillon breeding colony. Vet Pathol. 2016;53:1204–1209. doi: 10.1177/0300985816646430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowgier G, Lorusso E, Decaro N, Desario C, Mari V, Lucente MS, Lanave G, Buonavoglia C, Elia G. A molecular survey for selected viral enteropathogens revealed a limited role of Canine circovirus in the development of canine acute gastroenteritis. Vet Microbiol. 2017;204:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaccaria G, Malatesta D, Scipioni G, Di Felice E, Campolo M, Casaccia C, Savini G, Di Sabatino D, Lorusso A. Circovirus in domestic and wild carnivores: an important opportunistic agent? Virology. 2016;490:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis Version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu YX, Li WH. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics. 1993;133:693–709. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. RDP4: detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evolut. 2015;1:vev003. doi: 10.1093/ve/vev003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun W, Zhang H, Zheng M, Cao H, Lu H, Zhao G, Xie C, Cao L, Wei X, Bi J. The detection of canine circovirus in Guangxi, China. Virus Res. 2019;259:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li G, He W, Zhu H, Bi Y, Wang R, Xing G, Zhang C, Zhou J, Yuen KY, Gao GF. Origin, genetic diversity, and evolutionary dynamics of novel porcine circovirus 3. Adv Sci. 2018;5:1800275. doi: 10.1002/advs.201800275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piewbang C, Jo WK. Novel canine circovirus strains from Thailand: Evidence for genetic recombination. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7524. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25936-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.