Abstract

Griffithsin (GRFT) is a broad-spectrum antiviral protein that is effective against several glycosylated viruses. Here, we have evaluated the in vitro and in vivo antiviral activities of GRFT against Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection. In vitro experiments showed that treatment of JEV with GRFT before inoculation of BHK-21 cells inhibited infection in a dose-dependent manner, with 99 % inhibition at 100 μg/ml and a 50 % inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 265 ng/ml (20 nM). Binding assays suggested that binding of GRFT to JEV virions inhibited JEV infection. In vivo experiment showed that GRFT (5 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally before virus infection could completely prevent mortality in mice challenged intraperitoneally with a lethal dose of JEV. Our study also suggested that GRFT prevents JEV infection at the entry phase by targeting the virus. Collectively, our data demonstrate that GRFT is an antiviral agent with potential application in the development of therapeutics against JEV or other flavivirus infections.

Keywords: Antiviral Activity, Japanese Encephalitis Virus, Plaque Assay, Japanese Encephalitis Virus, Japanese Encephalitis Virus Infection

Introduction

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is a mosquito-borne virus belonging to the genus of Flavivirus, family of Flaviviridae. JEV infection causes a broad spectrum of clinical symptoms, ranging from asymptomatic infections to fever, encephalitis, and even death. Encephalitis caused by the infection is estimated to occur in 1 of 20 to 1000 cases [5, 12], with approximately 25 % of encephalitic patients dying and 50 % of the survivors developing permanent neurologic and/or psychiatric sequelae. The JEV genome is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA encoding a polyprotein of approximately 3,400 amino acids that is cleaved into three structural proteins (capsid [C], premembrane [prM] and envelope glycoprotein [E]) and seven nonstructural proteins [23]. The JEV envelope glycoprotein (53–55 kDa) contains two potential glycosylation sites [9] that are important for virus attachment, fusion, penetration, cell tropism, virulence and attenuation [14]. The JEV prM protein also contains one glycosylation site that is important for virus release and pathogenesis [13].

Griffithsin (GRFT), a plant-derived antiviral protein, is isolated from the red alga Griffithsia sp. Due to its lectin activity, GRFT has been shown to have broad-spectrum antiviral activity against several enveloped viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) [16], SARS-CoV [27], and hepatitis C virus (HCV) [15]. Recombinant GRFT produced in E. coli or in the Nicotiana benthamiana expression system does not alter its potent anti-HIV activity and its safety profile compared to native GRFT [16, 17]. GRFT is a dimeric lectin with six principal binding sites that can bind to the SARS-CoV spike glycoprotein (S) and prevent virus entry into target cells [27]. Because of the presence of glycans on the JEV virion, we investigated whether GRFT displays antiviral activity against JEV infection. Here, we demonstrate that GRFT inhibits JEV entry into host cells at nanomolar concentrations. Furthermore, we show that the inhibition was due to the binding ability of GRFT to the glycans on JEV virions. Finally, we show that GRFT protects BALB/c mice from challenge with a lethal dose of JEV. In summary, our data establish that GRFT is an antiviral agent that is potentially applicable in the development of therapeutics against JEV or other flavivirus infections.

Materials and methods

Cell, virus and animal

Baby hamster kidney (BHK)-21 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) containing 10 % heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C and 5 % CO2.

The Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) strain NJ2008 (GenBank accession no. GQ918133) was propagated and titrated by plaque assay in BHK-21 cells.

BALB/c mice (2 weeks old) were purchased from the Animal Center of Nanjing Army Hospital (Nanjing, China) and handled according to the ethical guidelines of Nanjing Agricultural University, China. The 50 % lethal dose (LD50) of JEV in BALB/c mice was determined by the method of Reed and Munech [19].

De novo synthesis, construction, expression and purification of recombinant GRFT

Five pairs of primers were designed (Table 1) based on the GRFT sequence (GenBank ID: FJ594069.1) to synthesize the GRFT gene de novo by the splicing by overlap extension PCR (SOE-PCR) method [7]. The full-length GRFT PCR product (375 bp) was digested with NdeI and XhoI restriction enzymes and ligated into pCold-I vector (Takara Bio Inc.) that had been digested with the same enzymes. The construct was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing analysis.

Table 1.

List of primers used for the de novo synthesis of GRFT by splicing by overlap extension PCR (SOE-PCR)

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| P1 | |

| Forward | CTGAGTCCGACCTTCACCTTTGGATCCGGTGAGTACATCAGCAACATGACCATTCGTAG |

| Reverse | GACCCATGTTGGTTTCAAAGCTGATGTTGTCAATGTAGTCTCCACTACGAATGGTCATG |

| P2 | |

| Forward | CGATCATCATTGATGGTGTACATCACGGTGGCTCTGGTGGTAACCTGAGTCCGACCTTC |

| Reverse | GGTGTTTGCACTGCCACCAGATCCACCATACGGACCAAAGCGACGACCCATGTTGGTTT |

| P3 | |

| Forward | CATTGCAGTTCGTAGTGGCAGCTATCTGGATGCGATCATCATTGATGGTGTACATCACG |

| Reverse | CGTTGATCTGGATGACTTTCACGTTGCTCAGGGTGTTTGCACTGCCACCAGATCCACCA |

| P4 | |

| Forward | GGTGGTAGTGGTGGAAGTCCGTTCAGCGGTCTGAGCAGCATTGCAGTTCGTAGTGGCAG |

| Reverse | GTAGATGTCCAGGCTATCCAGATAGTCACCTGCACTACCGTTGATCTGGATGACTTTCA |

| P5 | |

| Forward | GTAATACATATGAGCCTGACCCATCGCAAGTTCGGTGGTAGTGGTGGAAGTCCGTTCAG |

| Reverse | GGGCGGCGCTCGAGGTACTGTTCATAGTAGATGTCCAGGCTATCCAGATAGTCACC |

The SOE-PCR primers (P1-forwad/P1-reverse, P2-forward/P2-reverse, P3-forward/P3-rerverse, P4-forward/P4-reverse and P5-forward/P5-reverse) for GRFT synthesis are presented in pairs (forward and reverse). The Nde1 and Xho1 restriction enzyme sequences are underlined and were introduced in P5-forward and P5-reverse, respectively

The N-terminal 6-His-tagged GRFT was expressed and purified as a dimer as described previously [11] with minor modifications. Briefly, E. coli Rosetta 2 cells (Novagen) were transformed with pCold-I-GRFT plasmid. A single colony was used to inoculate 10 ml of Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml), and the culture was grown at 37 °C overnight. The cultures were diluted in 1 liter of LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and grown to an A 600 value of 0.8 at 37 °C. Protein expression was induced by treating the cells with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) at 22 °C for 18 h. The cells were then harvested and resuspended in binding buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM PMSF). The cells were lysed by sonication followed by centrifugation at 9000 g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was applied to an immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC) column (Bio-Rad). GRFT was eluted with elution buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole). GRFT was further purified by gel filtration chromatography using a SuperdexTM 75 column (GE Healthcare) that had been equilibrated with PBS (10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, 137 mM NaCl and 2.7 mM KCl). The endotoxins from GRFT were removed using Detoxi-Gel Endotoxin Removing Gel gravity flow columns (Thermo Scientific). Purified GRFT was characterized by SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis. The concentration of GRFT was determined by Bradford assay, and GRFT was stored at -80 °C until use.

Production of anti-GRFT polyclonal antibodies and anti-JEV-EDIII monoclonal antibody

A New Zealand rabbit was inoculated subcutaneously with 500 μg of GRFT emulsified in Freund’s complete adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich). Booster doses were administered at weeks 1, 2 and 3 with 500 μg of GRFT emulsified in Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. Finally, rabbit serum was collected at week 4. Both western blot analysis and ELISA were performed to evaluate the immunoreactivity between GRFT and its polyclonal antibodies.

A monoclonal antibody against the JEV envelope glycoprotein was produced by immunizing mice with purified JEV envelope glycoprotein domain III expressed in E. coli expression system. The monoclonal antibody was generated as described previously [8] and produced as ascites in BALB/c mice by injecting them with the hybridoma. Antibody was purified by protein A chromatography and characterized by western blot analysis and ELISA.

Cytotoxicity assay

BHK-21 cells grown in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well were incubated in the presence of GRFT (1.0-500 μg/ml) for 72 h. The cytotoxicity was assessed by measuring the activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the culture medium using an LDH diagnostic kit (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions and analyzed by regression analysis.

Plaque assay

BHK-21 cells at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well in a 24-well plate were incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h in the presence of GRFT/JEV mixture or supernatant of homogenized mouse brain tissue. The cells were washed and incubated in DMEM containing 2 % FCS (maintenance medium). Forty-eight hours later, the cell supernatant was diluted and used to inoculate BHK-21 cells at a density of 1. 2 × 106 cells/well in a 6-well plate for 1.5 hrs. The medium was then removed and replaced with agar overlay medium containing 2 % agar and 4 % FCS. The plates were incubated for 3-4 days at 37 °C, and the cells were stained with 0.1 % methylene blue to observe plaque formation. The 50 % inhibitory concentration (IC50) was determined.

The antiviral activity of GRFT assayed by quantitative real-time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

JEV genomic RNA was extracted from infected cells using TRIzol (Takara) and used to synthesize cDNA by reverse transcription (RT) utilizing PrimeScript® RT Master Mix Perfect Real Time Kit (TaKaRa). Real-time PCR was performed using an SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ Kit (Takara) on ABI PRISM 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The data were analyzed by the 2-ΔΔCt approach, and the quantitative expression of the target gene was normalized to β-actin mRNA in the same samples [20, 24]. The sequences of the primers used in the study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sequences of primers used for real-time PCR

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| JEV (NS1) | Forward: ACACTCGTCAGATCACAGGTTCA |

| Reverse: GCCAGAAACATCACCAGAAGG | |

| β-Actin (BHK-21 cells) | Forward: CATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCCAAC |

| Reverse: ATGGAGCCACCGATCCACA |

NS1, JEV nonstructural gene 1

Measurement of antiviral activity of GRFT by western blot analysis

JEV (MOI = 0.01) was premixed with GRFT (1.0, 3.2, 10, 32 and 100 μg/ml) for 1.5 h. BHK-21 cells at a density of 1.2 × 106 cells/well were then incubated with the mixture for 1.5 h. The cells were washed and incubated in DMEM containing 2 % FCS. After 48 h, the cells were washed, scraped, and lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 % Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1 % SDS, 5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.1 mM PMSF) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 30 min). The proteins in the supernatant were separated by 10 % SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore), blocked, and incubated with anti-JEV monoclonal antibody (1:10) or anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich). The membrane was then incubated with a 1/5000 dilution of horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich), and immunoreactive bands were visualized using ECL (Amersham).

Assay of virucidal activity of GRFT against JEV infection

In the first experiment, 105 PFU of JEV was incubated with medium containing GRFT (0.1, 1 and 10 μg/ml) or with control medium (no GRFT) for 1.5 h at 37 °C. The samples were diluted to reduce the concentration of GRFT below the IC50 value, and the remaining infectivity was determined by plaque assay in BHK-21 cells. The 50 % virucidal concentration (VC50), the concentration required to inactivate virions by 50 %, was calculated. In the second experiment, the cells were incubated with medium containing GRFT (0.1, 1 and 10 μg/ml) or with control medium (no GRFT) for 1.5 h at 37 °C and washed before they were incubated with the virus. A plaque assay was carried out to assess the virucidal activity of GRFT.

The antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV infection at different multiplicities

To evaluate the effect of different viral doses (MOIs) on the antiviral activity of GFRT, we preincubated GRFT at two concentrations with different doses of JEV (32 μg/ml GRFT with JEV [MOI = 0.01, 0.1] or 100 μg/ml GRFT with JEV [MOI = 1, 10]) for 1.5 h. BHK-21 cells were then treated with the mixture for 1.5 h. The cells were washed and incubated either for plaque assay or for western blot analysis.

Pulldown assay

A pulldown assay was performed according to a method described previously with some modifications [25]. His-tagged GRFT (5 μg) was incubated with 50 μl of IMAC beads (Novagen) in 0.5 ml binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5 % NP-40) for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 2000 g for 2 min. The pelleted beads were washed three times to remove the unbound GRFT. For washing, the pelleted beads were resuspended in 0.5 ml washing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 0.1 % Nonidet P-40 [NP-40]) and centrifuged at 2000 g for 2 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The virus (MOI = 0.1) was then incubated with the beads for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were then washed three times with washing buffer to remove the unbound viruses as described above. The beads were boiled in 1 × SDS buffer (25 μl) and subjected to western blot analysis using anti-JEV monoclonal antibody.

Co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP) assay

GRFT (5 μg) was preincubated with the virus (MOI = 0.1) for 2 h at 4 °C with gentle agitation. At the same time, 50 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia) washed with Co-IP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1 % Triton X-100) was incubated with rabbit anti-GRFT polyclonal antibodies (1:100) in PBS for 2 h at 4 °C with gentle agitation. The JEV-GRFT mixture was then incubated with the pretreated protein G-Sepharose beads for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed three times with Co-IP buffer, resuspended in 1 × SDS buffer (25 μl), boiled, and subjected to western blot analysis using anti-JEV monoclonal antibody.

In vivo evaluation of antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV infection

The toxicity of GRFT was first evaluated in 2-week-old BALB/c mice (n = 5) by administering 5 mg/kg GRFT intraperitoneally (i.p.) and evaluating the change in weight for 30 days in comparison to untreated mice.

The in vivo efficacy of GRFT against JEV infection was evaluated in BALB/c mice using a peripheral challenge model [18, 26]. The first group (negative control, n = 12) was injected intraperitoneally with PBS, followed by intracerebral injection of 30 μl of 1 % sterile starch 2 h later [22]. The second group (GRFT treated, n = 12) was first injected intraperitoneally with GRFT (5 mg/kg), and the third group (virus control, n = 12) was first injected intraperitoneally with PBS, and 4 h later, both the second and the third group were challenged i.p. with a 100 % lethal dose (2 × LD50) of JEV followed by intracerebral injection with 30 μl of starch (to breach the blood-brain barrier) 2 h later. In GRFT-treated mice, the level of GRFT was maintained by administering two doses of GRFT (2.5 mg/kg) i.p. daily for 4 days [18]. The mice were examined daily for the development of symptoms and death. Mice were sacrificed randomly, and their brains were collected on day 4 postinfection (negative control, virus control and GRFT-treated mice) and at the end of the observation (GRFT-treated mice). The mouse brain was removed aseptically, homogenized manually in sterile PBS (2 ml) and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was harvested, filtered, diluted, and subjected to western blot analysis and plaque assay.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained from different experiments were recorded as the mean ± standard deviation (S. D.) and subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the SPSS data analysis software (version 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences between means were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

De novo synthesis, construction, expression and purification of recombinant GRFT

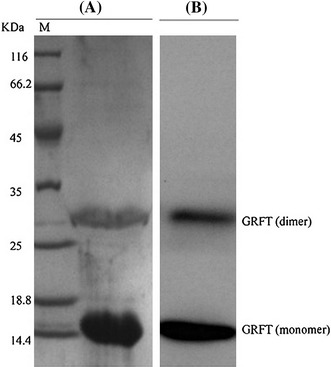

The GRFT gene was synthesized de novo using the SOE-PCR method (data not shown). The GRFT gene was ligated to the expression vector pCold-I. GRFT was expressed and purified from E. coli expression system. The purified protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Coomassie blue staining) and western blot analysis using an anti-His monoclonal antibody. We observed a dimer of GRFT in SDS-PAGE and western blot (Fig. 1A, B), which is consistent with a previous report [11].

Fig. 1.

Analysis of purified GRFT. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified GRFT. M indicates the marker sizes (kDa). Note the presence of dimeric (29 kDa) and monomeric (14.5 kDa) forms of GRFT. (B) Western blot analysis of purified GRFT using anti-His monoclonal antibody

In vitro evaluation of antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV infection

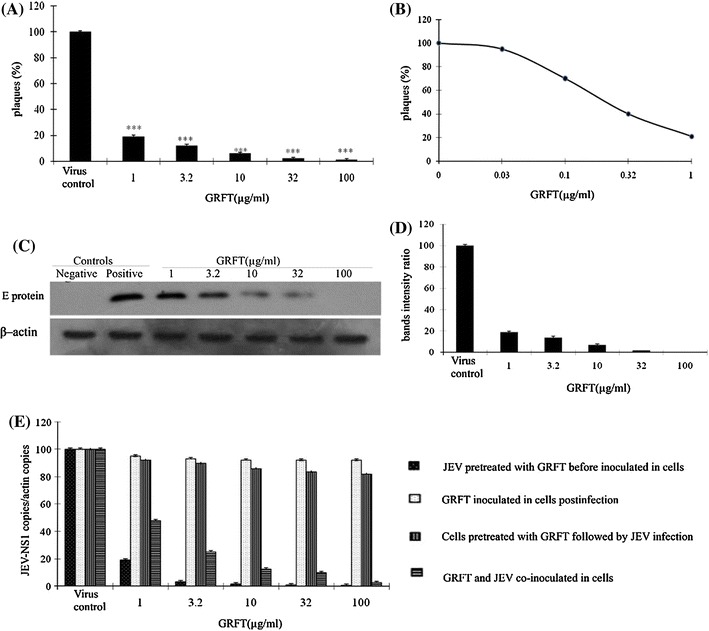

To investigate the ability of GRFT to inhibit JEV infection in BHK-21 cells, we first performed a plaque assay. Our results revealed that incubation of BHK-21 cells with premixed JEV/GRFT reduced virus infection in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). The percentage of inhibition was 82 % (P < 0.05) and 99 % (P < 0.001) at 1.0 μg/ml and 100 μg/ml GRFT, representing a 50 % inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 265 ng/ml (20 nM) (Fig. 2B) without in vitro toxicity (up to 500 μg/ml) (data not shown). Treatment of JEV with GRFT before inoculation of BHK-21 cells also reduced the expression level of the viral envelope protein in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2C) as revealed by western blot analysis using an anti-JEV envelope protein monoclonal antibody. The expression level of the viral envelope protein was below the level of detection when JEV was premixed with 100 μg/ml GRFT. The western blot signals were quantified using ImageJ 1.45 software and plotted versus GRFT concentrations (Fig. 2D). These results indicated that GRFT could significantly prevent JEV infection in BHK-21 cells.

Fig. 2.

In vitro evaluation of the antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV infection in BHK-21 cells. (A) Plaque assay. Virus was treated with different concentrations of GRFT before inoculation of the cells. (B) The IC50 value of GRFT. The virus was treated with GRFT (0.03, 0.1, 0.32 and 1.0 μg/ml) for 2 h before inoculating the cells for 2 h. A plaque assay was performed to determine the IC50 of GRFT. (C) GRFT antiviral activity assayed by western blot analysis using anti-JEV monoclonal antibody. (D) Densitometric analysis of the western blot was performed with ImageJ 1.45 m (National Institutes of Health (NIH) and plotted versus GRFT concentration. (E) The antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV infection evaluated by qRT-PCR, normalized with β-actin. Data are represented as mean ± SD. * = P < 0.001

To determine whether the anti-JEV activity of GRFT was due to its interaction with the viral particle as previously suggested [10], we evaluated the changes in the JEV genomic RNA level using qRT-PCR. We found that the viral genomic RNA level was significantly reduced in a dose-dependent manner up to 99 % reduction at 100 μg/ml of GRFT (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2E) when BHK-21 cells were incubated in the presence of premixed JEV/GRFT, suggesting that GRFT could interact directly with virus particles and thereby reduce their infectivity. We further investigated whether GRFT inhibits JEV infection by interacting with the cells. BHK-21 cells were incubated with GRFT for 1.5 h before virus infection. The result showed that preincubation of BHK-21 cells with GRFT had no significant inhibitory effect on JEV infection (Fig. 2E), demonstrating that GRFT did not interact with the receptors required for the virus entry. To determine if GRFT is effective after infection has already been established, we first inoculated the cells with the virus for 1.5 h. The cells were then washed three times with PBS and incubated in the presence of GRFT for 1.5 hrs. We did not observe any changes in the level of JEV genomic RNA at 48 hpi (Fig. 2E), suggesting that GRFT acts at early steps in the life cycle of the virus. Finally, we added GRFT simultaneously with JEV in BHK-21 cells to investigate whether GRFT initiates antiviral activity immediately upon contact with JEV. As shown in Fig. 2E, GRFT inhibited JEV infection in BHK-21 cells, which is consistent with the immediate effect of GRFT on HIV-1 infection [10].

Assay of virucidal activity of GRFT against JEV infection

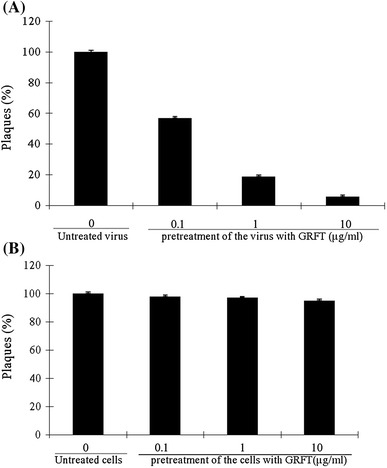

To assess the effect of GRFT on viral infectivity, a virucidal assay was performed. The result revealed that GRFT exhibited concentration-dependent virucidal activity as well as a significant inhibitory effect on residual infectivity compared to the controls (Fig. 3A). The VC50 was 105 ng/ml, and this value was below the IC50, suggesting that GRFT possesses a potent virucidal capacity. Conversely, no protection was observed when BHK-21 cells were first treated with GRFT, washed and then infected with the virus (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that GRFT acts as a virucide, similar to its effect on HIV-1 infection [16].

Fig. 3.

Assay of the virucidal activity of GRFT against JEV infection. (A) The virus was pretreated with different concentrations of GRFT for 1.5 h, and the mixture was diluted below the IC50 of GRFT before inoculating the cells. The remaining infectivity was determined by plaque assay. (B) The cells were pretreated with GRFT for 1.5 hrs and washed three times with PBS before inoculated with the virus for 1.5 h. The plaque assay was performed, and the results were analyzed. The bars represent the means and SD

The antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV infection at different multiplicities of infection

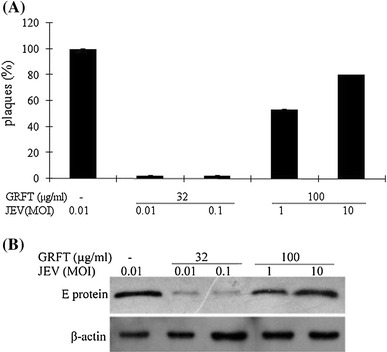

The plaque assay results showed that GRFT exhibited greater inhibition of virus infection when the cells were infected at a lower MOI (0.01 and 0.1) (Fig. 4A). Conversely, when the cells were infected at a higher MOI (1 and 10), a substantial amount of virus was released even when the GRFT concentration was increased to as high as 100 μg/ml. Western blot analysis also confirmed this (Fig. 4B). Therefore, the efficacy of GRFT was inversely related to the multiplicity of infection, suggesting that a high MOI reduced the anti-JEV activity of GRFT. For this reason, the continuous supplement of GRFT might be necessary to exert its antiviral activity.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of the effect of the MOI on the antiviral activity of GRFT in BHK-21 cells. Different concentrations of GRFT were incubated with virus at different MOIs for 1.5 h. BHK-21 cells were then incubated in the presence of the GRFT/JEV mixture for 1.5 h. The cells were washed before adding DMEM containing 2 % FCS and re-culturing. Plaque assay (A) and western blot analysis (B) were performed at 48 hpi

GRFT interacts with JEV virions

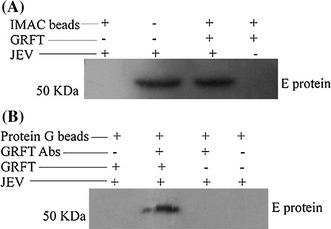

We performed a pulldown assay to demonstrate the mechanism of the anti-JEV activity of GRFT, as GRFT can bind to N-linked glycans present on virus glycoproteins [27, 28]. We used anti-JEV envelope protein antibody to detect the interaction between GRFT and JEV virions. The JEV envelope glycoprotein (53 kDa) was detected only in the presence of GRFT (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, co-immunoprecipitation of GRFT-JEV complexes with anti-GRFT polyclonal antibodies conjugated with protein-G Sepharose beads demonstrated that JEV could be co-immunoprecipitated in the presence of GRFT, but not in the absence of GRFT (Fig. 5B). These data suggested that the antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV was due to its interaction with the virus particle.

Fig. 5.

GRFT interacts with JEV virions. (A) Pulldown assay. IMAC beads (50 μl) were preincubated with His-tagged GRFT (5 μg), washed, and incubated with the virus (MOI = 0.1) for 1.5 h. The beads were washed, and the JEV envelope protein was detected by western blot analysis using an anti-JEV monoclonal antibody. The JEV envelope protein could only be detected in the presence of GRFT. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation assay. GRFT (5 μg) was preincubated with the virus (MOI = 0.1) for 2 h. Protein G-Sepharose beads (50 μl) were incubated with rabbit anti-GRFT polyclonal antibodies for 2 h. The JEV/GRFT mixture was then incubated with the pretreated protein G-Sepharose beads for 2 h. The beads were washed, and JEV envelope protein was detected by western blot analysis using anti-JEV monoclonal antibody. The JEV envelope protein could only be co-immunoprecipitated in the presence of GRFT

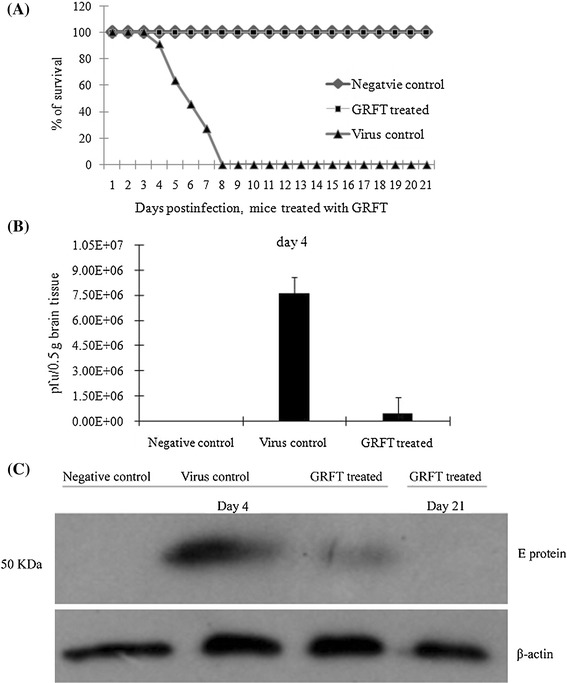

In vivo evaluation of the antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV infection

GRFT (5 mg/kg) administered i.p. in BALB/c mice did not show in vivo toxicity (data not shown). Thus, we further evaluated the in vivo antiviral capacity of GRFT. We observed 100 % survival of mice treated with GRFT before challenging with a lethal dose of JEV compared to the death of all of the mice between days 4 and 8 postinfection in the virus control group (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B, GRFT treatment significantly reduced the virus titers in mouse brain on day 4 postinfection (4.2 × 105 pfu/0.5 g brain tissue) compared to the virus control (7.6 × 106 pfu/0.5 g brain tissue). In agreement with this observation, mice treated with GRFT also had reduced viral antigen load in the brain tissue as revealed by western blot analysis using anti-JEV envelope protein antibody (Fig. 6C). No virus envelope glycoprotein was detected in brain tissue of surviving mice on day 21 in the GRFT-treated group (Fig. 6C). These results showed that treatment with GRFT completely protected mice from the challenge of a lethal dose of JEV.

Fig. 6.

In vivo evaluation of the antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV infection. Three groups of BALB/c mice (negative control, virus control and GRFT-treated) were used in the study. (A) Virus challenge experiment. Note the 100 % survival in the GRFT-treated group compared to the mice in the virus control group, which died between days 4 and 8 postinfection. (B) The virus titers in mouse brain tissue evaluated by plaque assay. (C) JEV envelope protein expression in the mouse brain tissue (days 4 and 21) detected by western blot analysis using anti-JEV monoclonal antibody

Discussion

It has been reported that GRFT has distinct antiviral activity against several viruses, and the antiviral activity of recombinant GRFT is similar to that of native GRFT [11]. Therefore, in this study we evaluated the antiviral activity of recombinant GRFT against JEV infection in vitro and in vivo.

Our in vitro results showed that the interaction between GRFT and JEV virions resulted in a significant inhibition of virus infection in BHK-21 cells at nanomolar concentrations. A monomer of GRFT contains three carbohydrate-binding sites that bind to N-linked glycans on virus glycoproteins [27]. GRFT exists as a domain-swapped homodimer; it has six separate binding sites that are important for its antiviral potency [27]. Binding of GRFT to virus glycoproteins may inhibit the conformational change required for virus–target cell attachment and subsequent fusion. It has been reported that there is a difference in the antiviral activity of GRFT against SARS-CoV and HIV-1, which is likely due to the differences in the binding affinity between GRFT and viral envelope glycoproteins [18]. Therefore, despite GRFT exerting its antiviral activity using similar mechanisms, the mode by which GRFT interacts with different viral glycoproteins is the main factor that influences the antiviral activity of GRFT against different viruses.

GRFT administered at 5 mg/kg before JEV infection could provide 100 % protection in mice challenged with a lethal dose of JEV, indicating the ability of GRFT to saturate the circulating JEV and restrain virus infectivity. This finding is consistent with what has been observed in a study on SARS-CoV [18]. The absence of JEV proteins in mice at day 21 postchallenge indicated that the virus is cleared over time [21], suggesting a prophylactic value of GRFT against JEV infection. An in vivo study on the antiviral activity of GRFT against HCV (a flavivirus) infection demonstrates that GRFT can delay the kinetics of infection when injected subcutaneously [15]. In our mice experiment, we observed that the intraperitoneal administration of GRFT provided a survival advantage to mice infected with a lethal dose of JEV.

It has been shown that the presence of N-glycans in HIV-1 and HCV restricts the antibody neutralizing response and protects the virus from being recognized by animal immune systems [3]. One study has demonstrated that GRFT can also interact with glycans on HIV-1 gp120, exposing the CD4 binding site (CD4bs) and increasing the sensitivity to CD4bs antibodies [2]. The conformational alteration caused by the interaction of GRFT with JEV glycoproteins [6] may expose hidden epitopes of the JEV glycoprotein, allowing the immune system to become actively involved in inhibiting JEV infection [3]. This is an additional property of GRFT that makes it a novel antiviral agent against JEV infection.

The broad-spectrum antiviral activity of GRFT against taxonomically distinct viruses is due to its ability to bind a broader spectrum of oligosaccharides [16] than other antiviral lectins such as cyanovirin-N (CV-N) [4] and scytovirin (SVN) [1]. This indiscriminate activity of GRFT represents a challenge for developing GRFT as an antiviral agent. However, in some ways, the broad-spectrum antiviral activity of GRFT may be an advantage, because it will exert its activity against most threatening viruses possessing a glycosylated envelope protein. In conclusion, this study demonstrates the antiviral activity of GRFT against JEV infection in vitro and in vivo. Future work on the pharmacokinetics of GRFT may lead to the development of GRFT as antiviral agent against the infection of JEV or other flaviviruses.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the priority academic program development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

References

- 1.Adams EW, Ratner DM, Bokesch HR, McMahon JB, O’Keefe BR, Seeberger PH. Oligosaccharide and glycoprotein microarrays as tools in HIV glycobiology: glycan-dependent gp120/protein interactions. Chem Biol. 2004;11:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexandre KB, Gray ES, Pantophlet R, Moore PL, McMahon JB, Chakauya E, O’Keefe BR, Chikwamba R, Morris L. Binding of the mannose-specific lectin, griffithsin, to HIV-1 gp120 exposes the CD4-binding site. J Virol. 2011;85:9039. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02675-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balzarini J. Targeting the glycans of glycoproteins: a novel paradigm for antiviral therapy. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:583–597. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolmstedt AJ, O’Keefe BR, Shenoy SR, McMahon JB, Boyd MR. Cyanovirin-N defines a new class of antiviral agent targeting N-linked, high-mannose glycans in an oligosaccharide-specific manner. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:949–954. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt WE. From the World Health Organization: development of dengue and Japanese encephalitis vaccines. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:577–583. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.3.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bressanelli S, Stiasny K, Allison SL, Stura EA, Duquerroy S, Lescar J, Heinz FX, Rey FA. Structure of a flavivirus envelope glycoprotein in its low-pH-induced membrane fusion conformation. EMBO J. 2004;23:728–738. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y, Qiao J, Li Y, Lu W. De novo synthesis, constitutive expression of Aspergillus sulphureus β-xylanase gene in Pichia pastoris and partial enzymic characterization. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:579–585. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0978-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu YH, Chan Y-L, Li T-L, Wu CJ. Inhibition of Japanese encephalitis virus infection by the sulfated polysaccharides extracts from Ulva lactuca. Mar Biotechnol. 2011;12:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10126-011-9428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutta K, Rangarajan PN, Vrati S, Basu A. Japanese encephalitis: pathogenesis, prophylactics and therapeutics. Curr Sci. 2010;98:326. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emau P, Tian B, O’keefe B, Mori T, McMahon J, Palmer K, Jiang Y, Bekele G, Tsai C. Griffithsin, a potent HIV entry inhibitor, is an excellent candidate for anti-HIV microbicide. J Med Primatol. 2007;36:244–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2007.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giomarelli B, Schumacher KM, Taylor TE, Sowder RC, 2nd, Hartley JL, McMahon JB, Mori T. Recombinant production of anti-HIV protein, griffithsin, by auto-induction in a fermentor culture. Protein Expres Purif. 2006;47:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang C. Studies of Japanese encephalitis in China. Adv Virus Res. 1982;27:71–101. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60433-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JM, Yun SI, Song BH, Hahn YS, Lee CH, Oh HW, Lee YM. A single N-linked glycosylation site in the Japanese encephalitis virus prM protein is critical for cell type-specific prM protein biogenesis, virus particle release, and pathogenicity in mice. J Virol. 2008;82:7846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00789-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindenbach BD, Thiel H-Ju, Rice CM. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2007. pp. 1108–1109. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meuleman P, Albecka A, Belouzard S, Vercauteren K, Verhoye L, Wychowski C, Leroux-Roels G, Palmer KE, Dubuisson J. Griffithsin has antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus. Antimicrob Agents Ch. 2011;55:5159–5167. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00633-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori T, O’Keefe BR, Sowder RC, 2nd, Bringans S, Gardella R, Berg S, Cochran P, Turpin JA, Buckheit RW, Jr, McMahon JB, Boyd MR. Isolation and characterization of griffithsin, a novel HIV-inactivating protein, from the red alga Griffithsia sp. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9345–9353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Keefe BR, Vojdani F, Buffa V, Shattock RJ, Montefiori DC, Bakke J, Mirsalis J, d’Andrea AL, Hume SD, Bratcher B. Scaleable manufacture of HIV-1 entry inhibitor griffithsin and validation of its safety and efficacy as a topical microbicide component. PNAS. 2009;106:6099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901506106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Keefe BR, Giomarelli B, Barnard DL, Shenoy SR, Chan PKS, McMahon JB, Palmer KE, Barnett BW, Meyerholz DK, Wohlford-Lenane CL. Broad-spectrum in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the antiviral protein griffithsin against emerging viruses of the family Coronaviridae. J Virol. 2010;84:2511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02322-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Epidemiol. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmittgen TD, Zakrajsek BA, Mills AG, Gorn V, Singer MJ, Reed MW. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction to study mRNA decay: comparison of endpoint and real-time methods. Anal Biochem. 2000;285:194–204. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sebastian L, Desai A, Shampur MN, Perumal Y, Sriram D, Vasanthapuram R. N-methylisatin-beta-thiosemicarbazone derivative (SCH 16) is an inhibitor of Japanese encephalitis virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Virol J. 2008;5:64. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sebastian L, Desai A, Madhusudana SN, Ravi V. Pentoxifylline inhibits replication of Japanese encephalitis virus: a comparative study with ribavirin. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sumiyoshi H, Mori C, Fuke I, Morita K, Kuhara S, Kondou J, Kikuchi Y, Nagamatu H, Igarashi A. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Japanese encephalitis virus genome RNA. Virology. 1987;161:497–510. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winer J, Jung CKS, Shackel I, Williams PM. Development and validation of Real-Time quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for monitoring gene expression in cardiac myocytesin vitro. Anal Biochem. 1999;270:41–49. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan Y, Kang B. Regulation of Vid-dependent degradation of FBPase by TCO89, a component of TOR Complex 1. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:361. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Y, Ye J, Yang X, Jiang R, Chen H, Cao S. Japanese encephalitis virus infection induces changes of mRNA profile of mouse spleen and brain. Virol J. 2011;8:80. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziolkowska NE, O’Keefe BR, Mori T, Zhu C, Giomarelli B, Vojdani F, Palmer KE, McMahon JB, Wlodawer A. Domain-swapped structure of the potent antiviral protein griffithsin and its mode of carbohydrate binding. Structure. 2006;14:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziółkowska NE, Wlodawer A. Structural studies of algal lectins with anti-HIV activity. Acta Biochim Pol. 2006;53:617–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]