Abstract

Background

Various beneficial effects derived from neuraxial blocks have been reported. However, it is unclear whether these effects have an influence on perioperative mortality and major pulmonary/cardiovascular complications.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to summarize Cochrane systematic reviews that assess the effects of neuraxial blockade on perioperative rates of death, chest infection and myocardial infarction by integrating the evidence from all such reviews that have compared neuraxial blockade with or without general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia alone for different types of surgery in various populations. Our secondary objective was to summarize the evidence on adverse effects (an adverse event for which a causal relation between the intervention and the event is at least a reasonable possibility) of neuraxial blockade. Within the reviews, studies were selected using the same criteria.

Methods

A search was performed in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews on July 13, 2012. We have (1) included all Cochrane systematic reviews that examined participants of any age undergoing any type of surgical (open or endoscopic) procedure, (2) compared neuraxial blockade versus general anaesthesia alone for surgical anaesthesia or neuraxial blockade plus general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia alone for surgical anaesthesia and (3) included death, chest infection, myocardial infarction and/or serious adverse events as outcomes. Neuraxial blockade could consist of epidural, caudal, spinal or combined spinal‐epidural techniques administered as a bolus or by continuous infusion. Studies included in these reviews were selected on the basis of the same criteria. Reviews and studies were selected independently by two review authors, who independently performed data extraction when data differed from one of the selected reviews. Data were analysed by using Review Manager Version 5.1 and Comprehensive Meta Analysis Version 2.2.044.

Main results

Nine Cochrane reviews were selected for this overview. Their scores on the Overview Quality Assessment Questionnaire varied from four to six of a maximal possible score of seven. Compared with general anaesthesia, neuraxial blockade reduced the zero to 30‐day mortality (risk ratio [RR] 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.53 to 0.94; I2 = 0%) based on 20 studies that included 3006 participants. Neuraxial blockade also decreased the risk of pneumonia (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.79; I2 = 0%) based on five studies that included 400 participants. No difference was detected in the risk of myocardial infarction between the two techniques (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.37; I2 = 0%) based on six studies with 849 participants. Compared with general anaesthesia alone, the addition of a neuraxial block to general anaesthesia did not affect the zero to 30‐day mortality (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.51; I2 = 0%) based on 18 studies with 3228 participants. No difference was detected in the risk of myocardial infarction between combined neuraxial blockade‐general anaesthesia and general anaesthesia alone (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.09; I2 = 0%) based on eight studies that included 1580 participants. The addition of a neuraxial block to general anaesthesia reduced the risk of pneumonia (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.98; I2 = 9%) after adjustment for publication bias and based on nine studies that included 2433 participants. The quality of the evidence was judged as moderate for all six comparisons.

No serious adverse events (seizure or cardiac arrest related to local anaesthetic toxicity, prolonged central or peripheral neurological injury lasting longer than one month or infection secondary to neuraxial blockade) were reported. The quality of the reporting score of complications related to neuraxial blocks was nine (four to 12 (median range)) of a possible maximum score of 14.

Authors' conclusions

Compared with general anaesthesia, a central neuraxial block may reduce the zero to 30‐day mortality for patients undergoing surgery with intermediate to high cardiac risk (level of evidence, moderate). Further research is required.

Keywords: Humans; Review Literature as Topic; Anesthesia, Epidural; Anesthesia, Epidural/adverse effects; Anesthesia, Epidural/methods; Anesthesia, General; Anesthesia, General/adverse effects; Anesthesia, Spinal; Anesthesia, Spinal/adverse effects; Anesthesia, Spinal/methods; Heart Arrest; Heart Arrest/prevention & control; Myocardial Infarction; Myocardial Infarction/mortality; Myocardial Infarction/prevention & control; Pneumonia; Pneumonia/mortality; Pneumonia/prevention & control; Postoperative Complications; Postoperative Complications/mortality; Postoperative Complications/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Effects of spinals and epidurals on perioperative death, myocardial infarction and pneumonia: an overview of Cochrane systematic reviews

Epidurals and spinals are anaesthetic techniques that block the transmission of painful stimuli from a surgical site to the brain at the level of the spinal cord. They allow the surgeon to perform surgery on the lower part of the abdomen (below the umbilicus) or on the lower limbs with no painful sensation while the person remains conscious. In this Cochrane overview, we summarized relevant randomized controlled trials from nine Cochrane systematic reviews, in which epidurals or spinals were compared as a method of replacing general anaesthesia or were added to general anaesthesia to reduce the quantity of narcotics or muscle relaxants required during general anaesthesia. The types of surgery included were caesarean section, abdominal surgery, repair of hip fracture, replacement of hip and knee joints and surgery to improve circulation in the legs.

When epidurals or spinals were used to replace general anaesthesia, the risk of dying during the surgery or within the following 30 days was reduced by approximately 29% (from 20 studies with 3006 participants). Also, the risk of developing pneumonia (chest infection) was reduced by 55% (from five studies with 400 participants). However, the risk of developing a myocardial infarction (heart attack) was the same for both anaesthetic techniques (from six studies with 849 participants).

When epidurals (and less frequently spinals) were used to reduce the quantity of other drugs required while general anaesthesia was used, the risk of dying during the surgery or within 30 days was the same for both anaesthetic techniques (from 18 studies with 3228 participants). Also, a difference was not detected for the risk of developing myocardial infarction (from eight studies with 1580 participants). The risk of developing pneumonia was reduced by approximately 30% when a correction was made for possible missing studies (from nine studies with 2433 participants).

No serious side effects (seizures, cardiac arrest, nerve damage lasting longer than one month or infection) were reported from the use of epidurals or spinals in these studies.

The quality of the evidence for all six comparisons was rated as moderate because of some imperfections in how the studies were carried out. Therefore further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in these results and may even change the results.

.

Background

Description of the condition

Despite major improvements in overall patient care (including anaesthetics and surgical techniques), postoperative death remains a reality. Death may occur following major infectious (superficial, deep, urinary tract or organ infection or sepsis), haematological (postoperative bleeding requiring transfusion, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus), cardiovascular (myocardial infarction, stroke), respiratory (pneumonia, unplanned intubation, prolonged mechanical ventilation), renal (acute kidney injury) and surgical (wound dehiscence, vascular graft loss) complications.

Description of the interventions

Regional blockade is commonly used to provide intraoperative anaesthesia and/or postoperative analgesia, with or without general anaesthesia, to patients undergoing surgery. Regional blockade refers to techniques in which conduction of painful stimuli is blocked at the level of the sensory nerve, the plexus or the spinal cord. Regional blockade at the level of the spinal cord is also described as neuraxial blockade. Unconsciousness and amnesia do not occur during regional blockade in the absence of complications or without sedation or general anaesthesia. For surgery, regional blockade may be used as an alternative to general anaesthesia or in combination with general anaesthesia as a replacement for opioids or neuromuscular blocking agents or to decrease the required doses of these two types of drugs. This overview examines neuraxial blockade used as a replacement for general anaesthesia during surgery or as a supplement to general anaesthesia during surgery.

How the intervention might work

Neuraxial blockade with or without general anaesthesia may reduce the incidence of some major complications that can lead to death such as pulmonary complications (Nishimori 2012), time to tracheal extubation (Guay 2006a; Nishimori 2012), cardiac dysrhythmias (Guay 2006a), venous thromboembolism (Parker 2004), blood transfusion (Guay 2006b), surgical site infection (Chang 2010) and acute kidney injury (Guay 2006a; Nishimori 2012). Maximal blood concentrations of stress response markers, such as epinephrine, norepinephrine, cortisol and glucose, are lower in patients for whom epidural analgesia is added to general anaesthesia (Guay 2006a).

Why it is important to do this overview

In 2000, Rodgers and colleagues published an extensive meta‐analysis that included data from 141 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 9559 participants and reported that intraoperative neuraxial blockade, with or without general anaesthesia, reduced the all‐cause mortality rate within 30 days of randomization (odds ratio (OR) 0.70; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54 to 0.90) compared with general anaesthesia alone (Rodgers 2000). The reported effect of neuraxial blockade on mortality from the meta‐analysis by Rodgers et al. may not reflect current practice. Furthermore, although Rodgers et al. concluded that a one‐third reduction in mortality rate would occur when a neuraxial block was added to general anaesthesia or when a neuraxial block was used to replace general anaesthesia, a wide CI (95% CI 0.53 to 1.41) around the former estimate of treatment effect precludes the conclusion that adding a neuraxial block to general anaesthesia reduces the mortality rate. Several Cochrane reviews have evaluated the effects of neuraxial blockade for various types of surgical populations. No synthesis of these reviews has been reported in an overview.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to summarize Cochrane systematic reviews that assess the effects of neuraxial blockade on perioperative rates of death, chest infection and myocardial infarction by integrating the evidence from all such reviews that have compared neuraxial blockade with or without general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia alone for different types of surgery in various populations. Our secondary objective was to summarize the evidence on adverse effects (an adverse event for which a causal relation between the intervention and the event is at least a reasonable possibility) of neuraxial blockade. Within the reviews, studies were selected using the same criteria.

Methods

Criteria for considering reviews for inclusion

We considered all Cochrane systematic reviews that:

included RCTs;

examined participants of any age undergoing any type of surgical (open or endoscopic) procedure;

compared neuraxial blockade versus general anaesthesia alone for the surgical anaesthesia, or compared neuraxial blockade plus general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia alone for the surgical anaesthesia; and

included death, chest infection, myocardial infarction or serious adverse events as outcomes.

Neuraxial blockade consisted of epidural, caudal, spinal or combined spinal‐epidural techniques administered as a bolus or by continuous infusion.

Search methods for identification of reviews

We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews on July 13, 2012, using the following terms:

#1 MeSH descriptor Anesthesia, Epidural explode all trees

#2 MeSH descriptor Nerve Block explode all trees

#3 MeSH descriptor Anesthetics, Local explode all trees

#4 MeSH descriptor Anesthesia, Intravenous explode all trees

#5 MeSH descriptor Analgesia, Epidural explode all trees

#6 MeSH descriptor Anesthesia, Caudal explode all trees

#7 ((epidural or caudal or spinal or spinal?epidural) near (techniq* or administ* or bolus* or infusion*)) or an?esthesia

#8 (an?esthesia or block* or analgesia) near (regional or local or neuraxial or nerve or caudal or spinal or epidural or lumbar or general)

#9 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8)

Data collection and analysis

We analysed the data using RevMan 5.1 (Review Manager Version 5.1) and Comprehensive Meta Analysis Version 2.2.044 (www.Meta‐Analysis.com).

Selection of reviews

One review author (JG) screened all abstracts of reviews identified by the search. The full reports of the potential reviews were obtained. Two review authors (JG, SK, NA, PC or SS) independently reviewed each report for inclusion.

Data extraction and management

From the included studies of selected reviews, studies were selected independently by two review authors (JG, SK, NA, PC or SS) using the same criteria as were used for the selection of reviews, with no language restriction. Data of selected studies were reextracted by one review author (JG) and were compared with the data included in the corresponding review. Any discrepancy was checked by a second review author (SK, NA, PC or SS).

Assessment of methodological quality of included reviews

Two of the review authors (JG and SK, NA, SS or PC) independently assessed the methodological quality of included reviews using a 10‐item index, the Overview Quality Assessment Questionnaire (OQAQ) (Oxman 1991). As the latest version of the risk of bias tool was unavailable when some of the Cochrane reviews were carried out, the methodological quality of included RCTs was reassessed using the current Cochrane tool for risk of bias.

Data synthesis

Studies were classified into two groups.

Neuraxial blockade versus general anaesthesia for the surgery.

Neuraxial blockade added to general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia alone for the surgery.

Random‐effects models were used, and the effects were expressed as risk ratios (RRs). Heterogeneity was quantified by the I2 statistic, with the data entered in the direction (benefit or harm) yielding the lowest value. A value > 25% was used as the cutoff point for exploration. A priori factors chosen included the following.

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status (1 or 2 vs 3 or higher).

Age (< 18 years vs 18 to < 70 years vs 70 years or older).

Type of surgery (high vs intermediate cardiac risk vs low cardiac risk) (ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines).

Type of neuraxial blockade (spinal vs epidural; lumbar vs thoracic epidural vs caudal).

Type of neuraxial drug (long‐acting opioid alone vs local anaesthetic alone vs local anaesthetic plus long‐acting opioid vs other adjuvants (e.g. clonidine, neostigmine, ketamine)).

Duration of neuraxial blockade (intraoperative only vs infusion continued for at least 48 hours after surgery).

Use of thromboprophylaxis (appropriate or not according to current standards).

Type of thromboprophylaxis (low‐molecular‐weight heparin, ximelagatran, fondaparinux or rivaroxaban vs regional blockade, pneumatic compression and aspirin vs warfarin).

Pregnancy.

Mode of analgesia in the control group (intravenous analgesia vs other routes).

For results in which the intervention produced an effect, a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or a number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) was calculated that was based on the odds ratio (http://www.nntonline.net/visualrx/).

Publication bias was assessed by using a funnel plot followed by Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill technique, a classical fail‐safe number (alpha 0.05, two‐tails) or the regtest for each outcome.

The quality of the body of evidence for each outcome was judged as high, moderate or low according to the system developed by the GRADE Working Group (Atkins 2004; Guyatt 2011). The first consideration is the study design, with RCTs considered of higher quality than observational studies. The quality of the body of evidence is lower if the risk of bias of included studies is serious/very serious, some inconsistency is noted (I2 value), the demonstration of effect is indirect, imprecision in the results is evident (95% CI around the effect size) or a risk of publication bias is identified (classical fail‐safe number or funnel plot). The quality of the evidence is higher if the amplitude of the effect size is large/very large (< 0.5 or > 2.0 being large), evidence suggests a dose response or the possible effect of confounding factors would reduce a demonstrated effect or suggest a spurious effect when results show no effect. With high quality of evidence, further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the estimated effect. When the quality is moderate, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Three review authors (JG, SK and NLP) independently applied these criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

For adverse effects of neuraxial blockade, all selected studies were assessed according to the seven criteria proposed by Stojadinovic A et al.: method of accrual, duration of data collection, definition of complication, morbidity and mortality rates, grade of complication severity, exclusion criteria and study follow‐up (Stojadinovic 2009). The following complications related to neuraxial blockade were sought specifically.

Mortality (anytime up to five years).

Seizure or cardiac arrest related to local anaesthetic toxicity (any significant prolonged neurological sequelae related to these events were to be described).

Prolonged central or peripheral neurological injury lasting longer than one month.

Infection secondary to neuraxial blockade.

Results

A total of 1158 titles/abstracts were screened. Of these, 304 were protocols, 844 were not relevant to neuraxial blockade used during surgery and one did not contain a control group with general anaesthesia. Therefore we retrieved and kept nine systematic reviews. These nine reviews included 117 trials. For Afolabi 2006, only three of 16 trials were retained (Dyer 2003; Hodgkinson 1980; Wallace 1995). Thirteen were excluded because they did not include any outcome of interest (Sener 2003; Datta 1983; Dick 1992; Hong 2003; Kavak 2001; Kolatat 1999; Korkmaz 2004; Lertakyamanee 1999; Mahajan 1992; Pence 2002; Petropoulos 2003; Yegin 2003) or had inadequate randomization (epidural and general anaesthesia used in alternate participants; Hollmen 1978). For Barbosa 2010, all four trials were retained (Bode 1996; Christopherson 1993; Cook 1986; Dodds 2007). For Choi 2003, of the 13 trials available, 12 were excluded because they evaluated different interventions (Bertini 1995; Capdevila 1999; Gustafsson 1986; Hendolin 1996; Hommeril 1994; Klasen 1999; Sharrock 1994; Weller 1991) or lacked any outcome of interest (D'Ambrosio 1999; Jorgensen 1991; Moiniche 1994; Singelyn 1998). Only one trial was retained (Wulf 1999). For Craven 2003, all four trials were excluded because they evaluated different interventions (William 2001) or lacked any outcome of interest (Krane 1995; Somri 1998; Welborn 1990). All 10 trials from Cyna 2008 were excluded because they did not include any outcome of interest (Bramwell 1982; Concha 1994; Gauntlett 2003; Lunn 1979; Mak 2001; Martin 1982; May 1982; Vater 1985; Weksler 2005; White 1983). For Jorgensen 2000, four of the 22 trials were retained (Cuschieri 1985; Liu 1995; Riwar 1992; Scheinin 1987). The remainder were excluded because they did not contain any outcome of interest (Ahn 1988; Cullen 1985; Rutberg 1984; Scott 1989; Wallin 1986; Wattwil 1989), studied different interventions (Asantila 1991; Beeby 1984; Brodner 2000; Cooper 1996; Delilkan 1993; Geddes 1991; George 1992; Lee 1988; Thoren 1989; Thorn 1992; Thorn 1996) or had inadequate randomization (Bredtmann 1990; anaesthetic technique attributed according to the date of surgery (even vs odd days)). For Nishimori 2012, one trial was excluded because it lacked any outcome of interest (Barre 1989). The remaining 12 trials were retained (Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Broekema 1998; Davies 1993; Garnett 1996; Kataja 1991; Norman 1997; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Reinhart 1989; Yeager 1987). For Parker 2004, 13 of the 26 trials were retained (Berggren 1987; Bigler 1985; Couderc 1977; Davis 1981; Davis 1987; Juelsgaard 1998; McKenzie 1984; McLaren 1978; Racle 1986; Tasker 1983; Ungemach 1993; Valentin 1986; White 1980), and 13 were excluded for inappropriate randomization (Adams 1990; by the date of operation), lack of any outcome of interest (Biffoli 1998; Bredahl 1991; Brichant 1995; Brown 1994; Casati 2003; Kamitani 2003; Maurette 1988; Svartling 1986; Wajima 1995) or lack of any intervention of interest (de Visme 2000; Eyrolle 1998; Spreadbury 1980). For Werawatganon 2005, of the nine trials available, four were excluded because they did not include any outcome of interest (Allaire 1992; George 1994; Kowalski 1992; Tsui 1997), and two (Bois 1997; Boylan 1998) were already included from another review. Three new trials were added (Carli 2001; Paulsen 2001; Seeling 1991). Altogether, we retained 40 studies for the new analysis (Afolabi 2006: n = 3; Barbosa 2010: n= 4; Choi 2003: n = 1; Craven 2003: n = 0; Cyna 2008: n = 0; Jorgensen 2000: n = 4; Nishimori 2012: n = 12; Parker 2004: n = 13; Werawatganon 2005: n = 3). Half of these studies compared a neuraxial block versus general anaesthesia (Berggren 1987; Bigler 1985; Bode 1996; Christopherson 1993; Cook 1986; Couderc 1977; Davis 1981; Davis 1987; Dodds 2007; Dyer 2003; Hodgkinson 1980; Juelsgaard 1998; McKenzie 1984; McLaren 1978; Racle 1986; Tasker 1983; Ungemach 1993; Valentin 1986; Wallace 1995; Wulf 1999), and half compared neuraxial block plus general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia alone (Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Broekema 1998; Carli 2001; Cuschieri 1985; Davies 1993; Garnett 1996; Kataja 1991; Liu 1995; Norman 1997; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Paulsen 2001; Peyton 2003; Reinhart 1989; Riwar 1992; Scheinin 1987; Seeling 1991; White 1980; Yeager 1987). All retained trials studied adult participants undergoing surgery with an intermediate (Berggren 1987; Bigler 1985; Carli 2001; Couderc 1977; Cuschieri 1985; Davis 1981; Davis 1987; Dyer 2003; Hodgkinson 1980; Juelsgaard 1998; Liu 1995; McKenzie 1984; McLaren 1978; Paulsen 2001; Racle 1986; Riwar 1992; Scheinin 1987; Tasker 1983; Ungemach 1993; Valentin 1986; Wallace 1995; White 1980; Wulf 1999) or high (Bode 1996; Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Christopherson 1993; Cook 1986; Davies 1993; Dodds 2007; Garnett 1996; Kataja 1991; Norman 1997; Norris 2001; Reinhart 1989) cardiac risk or with a mixture of both (Broekema 1998; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Seeling 1991; Yeager 1987). These surgeries were performed on the lower limb (Berggren 1987; Bigler 1985; Bode 1996; Christopherson 1993; Cook 1986; Couderc 1977; Davis 1981; Davis 1987; Dodds 2007; Juelsgaard 1998; McKenzie 1984; McLaren 1978; Racle 1986; Tasker 1983; Ungemach 1993; Valentin 1986; White 1980; Wulf 1999), in the intra‐abdominal cavity (Bois 1997; Boylan 1998; Broekema 1998; Carli 2001; Cuschieri 1985; Davies 1993; Dyer 2003; Garnett 1996; Hodgkinson 1980; Kataja 1991; Liu 1995; Norman 1997; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Paulsen 2001; Peyton 2003; Reinhart 1989; Riwar 1992; Scheinin 1987; Seeling 1991; Wallace 1995) or at various parts of the body (Yeager 1987). Three trials studied pregnant women undergoing caesarean section (Dyer 2003; Hodgkinson 1980; Wallace 1995).

Description of included reviews

We included nine Cochrane reviews in this overview (Appendix 1). The first Cochrane review (Afolabi 2006) reported on 16 studies that included 1586 pregnant women undergoing caesarean section under epidural‐spinal anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia. Neuraxial blockade reduced maternal blood loss, but general anaesthesia was chosen preferentially for a further surgery by a higher number of participants. No maternal deaths were reported. The second review (Barbosa 2010) included four studies and 696 participants undergoing lower limb revascularization under epidural/spinal anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia. Neuraxial blockade reduced the incidence of pneumonia. The third review (Choi 2003) included 13 studies with 606 participants undergoing total hip or knee replacement with epidural or systemic analgesia. Epidural analgesia reduced early postoperative pain scores and the incidence of sedation but increased the rates of urinary retention, itching and low blood pressure. The fourth review (Craven 2003) included three studies with 108 preterm infants undergoing inguinal hernia repair under spinal versus general anaesthesia. When sedated infants were excluded, spinal anaesthesia reduced the incidence of postoperative apnoea. The fifth review (Cyna 2008) included 10 studies with 721 male children undergoing circumcision with the addition of a caudal block, a penile block or systemic analgesia. Compared with a penile block, a caudal block increased the incidence of leg weakness (motor block). The sixth review (Jorgensen 2000) included 22 studies with 1023 participants undergoing abdominal surgery with the addition of an epidural containing a local anaesthetic versus systemic or epidural opioids. An epidural with a local anaesthetic may have hastened the return of bowel function. The seventh review (Nishimori 2012) included 13 studies with 1224 participants undergoing elective open aortic abdominal surgery with the addition of epidural analgesia or systemic opioids. Epidural analgesia reduced the duration of tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation by approximately 20%, and the overall risk of cardiovascular complications, myocardial infarction, acute respiratory failure (defined as extended need for mechanical ventilation), gastrointestinal complications and acute kidney injury, as well as pain scores, for up to three days. The eighth review (Parker 2004) included 22 studies with 2567 participants undergoing repair of a hip fracture. In this subpopulation, neuraxial blockade reduced the 30‐day mortality rate. The last review (Werawatganon 2005) included nine studies with 711 participants undergoing intra‐abdominal surgery with the addition of epidural analgesia or patient‐controlled intravenous opioids. Epidural analgesia reduced the six‐hour pain scores but increased the incidence of pruritus.

Methodological quality of included reviews

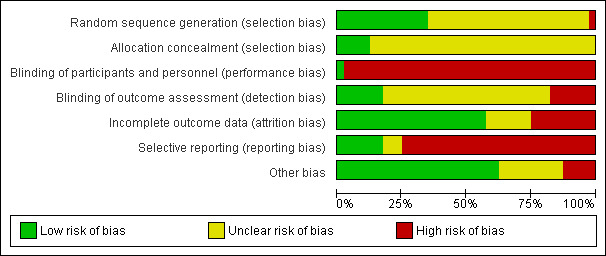

The overall quality of included reviews was average (Table 1). The quality of the 40 studies retained for reanalysis can be found in Figure 1.

1. Overview Quality Assessment Questionnaire.

| Item | Afolabi 2006 | Barbosa 2010 | Choi 2003 | Craven 2003 | Cyna 2008 | Jorgensen 2000 | Nishimori 2012 | Parker 2004 | Werawatganon 2005 |

| 1. Were the search methods reported? |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Was the search comprehensive? |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | Partially |

| 3. Were the inclusion criteria reported? |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4. Was selection bias avoided? |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | Yes | Partially |

Yes | Partially | Yes |

| 5. Were the validity criteria reported? |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6. Was validity of the included studies assessed appropriately? |

Partially | Yes | Partially | Partially | Partially | Partially | Yes | Partially | Yes |

| 7. Were the methods used to combine studies reported? |

Yes | Yes | Partially | Partially |

Partially |

Partially |

Yes | Yes | Partially |

| 8. Were the findings combined appropriately? |

Partially | Yes | Partially | Partially | Partially | Partially |

Partially | Partially | Yes |

| 9. Were the conclusions supported by the reported data? |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Partially | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. What was the overall scientific quality of the overview? (Likert scale from one to seven) |

Five | Six | Five | Four | Four | Five | Six | Five | Five |

Afolabi 2006: Recent studies are not included. “We updated the search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register on 1 October 2009 and added the results to the awaiting classification section". Did not use the new Cochrane scale, but the validity of the included trials was assessed appropriately. Nausea (I2 = 84%) and vomiting (I2 = 91%) should have been analysed with random‐effects models, and used/lack of prophylaxis and type of induction agent (propofol vs thiopental) could have been explored. For APGAR scores at one minute (I2 = 87%) and five minutes (I2 = 91%), the type of anaesthetic agents used (e.g. use of pancuronium in Kotalat’s study for one minute APGAR score of 6.7 ± 2.8) might have deserved to be mentioned. Publication bias assessment not performed.

Barbosa 2010: Publication bias assessment not performed.

Choi 2003: Last search in 2001. The quality of the studies was assessed with the JADAD score. High amount of heterogeneity for VAS scores at rest at four to six hours (I2 > 90%) analysed with fixed models. Publication bias assessment not performed.

Craven 2003: Last search in 2002. The definition for apnoea used in all studies differs from the protocol of the review. Moderate amount of heterogeneity (I2 = 60% and I2 = 65%) for apnoea/bradycardia analysed with fixed models. No exploration for heterogeneity because P value for heterogeneity not statistically significant (P value 0.20 and 0.06). Publication bias assessment not performed.

Cyna 2008: Last search 2008. Heterogeneity > 50% not explored. Publication bias assessment not performed.

Jorgensen 2000: Last search 1999, according to method section; inclusion of one study published in 2000. Inclusion of quasi‐randomized studies (as opposed to randomized studies only) in method section. The method section says: “Where heterogeneity in methodology, dosage of used drugs and type of surgery, across the reviewed studies prohibited a quantitative review, we restricted to perform a qualitative review.” Forest plots include quantitative analysis with I2 > 90%. Publication bias assessment not performed.

Nishimori 2012: Last search in 2010. For this review, the cutoff to use a random‐effects model was set at 30%, while the criterion prespecified for this overview was 25%. Publication bias assessment not performed.

Parker 2004: Last search 2004. The search for CENTRAL was limited to a part of it. Use of random‐effects models versus fixed‐effect models based on P value < 0.1 instead of on I2 values. Exclusion of studies on the basis of “neuroleptic technique” that could be considered total intravenous anaesthesia could be considered controversial. Publication bias assessment not performed.

Werawatganon 2005: Last search 2002. As the review title is “...for pain after intra‐abdominal surgery”, the reasons for inclusion of the term “labor” in the search (as opposed to caesarean section) are not obvious. It also is not obvious why studies with patient‐controlled epidural analgesia (which most of the time include a portion of basal continuous rate) were excluded instead of being studied as a subgroup, especially given the fact that IVPCA with and without a background infusion was included. Criteria to use a fixed‐effect or a random‐effects model or to decide when it was appropriate to explore heterogeneity were not predefined. Publication bias assessment not performed.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Appendix 2 contains details supporting the judgement of the quality of included studies. Appendix 3 gives the reasons for exclusion of studies included in the previous reviews but excluded from our analysis.

Effect of interventions

Neuraxial blockade compared with general anaesthesia

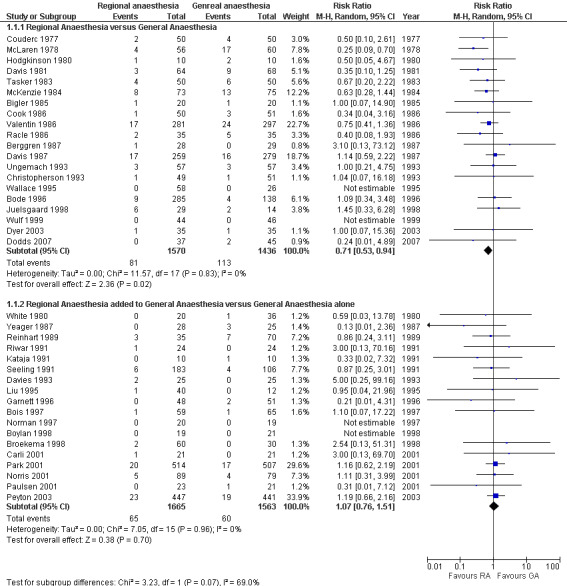

Compared with general anaesthesia, neuraxial blockade reduced the zero to 30‐day mortality (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.94; I2 = 0%; classical fail‐safe number = seven). The NNTB calculated on the OR was 44 (95% CI 27 to 228) for an incidence of 7.9% for general anaesthesia versus 5.2% for neuraxial blockade, based on 3006 participants (1570 for neuraxial blockade and 1436 for general anaesthesia). Cardiac risk was classified as intermediate for 76.5% (2300/3006) (intraperitoneal or orthopaedic surgery) and high for 23.5% (706/3006) (aortic or peripheral vascular surgery) of participants (Figure 2). With Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis, the adjusted RR was 0.72 (95% CI 0.54 to 0.95) while looking for missing studies to the right and was unchanged while looking for missing studies to the left. Egger's regression intercept did not indicate a small‐study effect. Mortality data were available for 896 participants for the one to six‐month follow‐up (RR 1.52, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.62) and for 726 participants at six to 12‐month follow‐up (RR 1.27, 95% CI 0.74 to 2.17).

2.

Forest plots for mortality zero to 30 days.

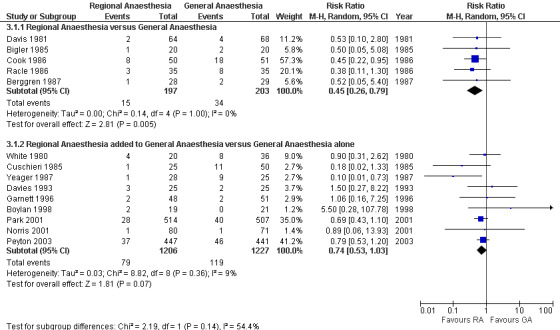

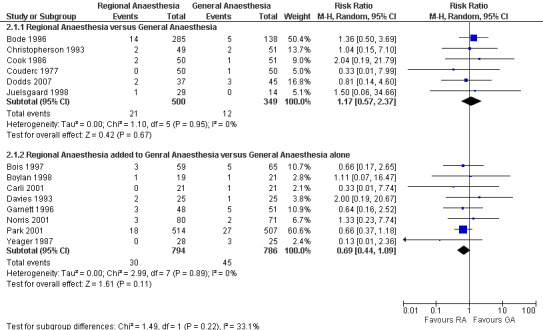

Neuraxial blockade also decreased the risk of pneumonia (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.79; I2 = 0%; classical fail‐safe number = three) (Figure 3) based on 400 participants in studies published between 1981 and 1987. The NNTB was 11 (95% CI 8 to 27) for incidences of 7.6% and 16.8% for neuraxial blockade and general anaesthesia, respectively. Egger’s regression intercept did not indicate a small‐study effect. The RR adjusted for a possible publication bias was 0.44 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.73). No difference in the risk of myocardial infarction was noted between neuraxial blockade and general anaesthesia (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.37; I2 = 0%) (Figure 4) based on 849 participants. No evidence of publication bias was found for this comparison.

3.

Forest plots for pneumonia zero to 30 days.

4.

Forest plots for myocardial infarction zero to 30 days.

Neuraxial blockade plus general anaesthesia compared with general anaesthesia alone

Adding a neuraxial blockade to general anaesthesia did not affect the mortality risk (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.51; I2 = 0%) (Figure 2) based on 3228 participants (1665 with a neuraxial block and 1563 without). With Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis, the effect was almost unchanged (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.59). The risk of myocardial infarction was not different between the two anaesthetic techniques (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.09; I2 = 0%) (Figure 4) based on 1580 participants (794 with a neuraxial block and 786 without). The power to detect a 25% reduction in incidence from 5.7% was only 0.25 (α = 0.05, two‐sided test). With an adjustment for a possible publication bias, the RR would be 0.72 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.13).

Likewise, the addition of a neuraxial block did not change the risk of pneumonia when a random‐effects model was used (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.03; I2 = 9%) (Figure 3) and was marginally suggestive of an effect when a fixed‐effect model was used (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.98) based on 2433 participants. For the random‐effects model, the power to detect a 25% reduction is 0.58 (α = 0.05, two‐sided test) from an incidence of 9.5%. For the fixed‐effect model, the NNTB was 40 (95% CI 24 to 387). Egger’s regression intercept did not indicate a small‐study effect. The funnel plot revealed that two studies might be missing on the left side. With Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis, the adjusted RR was 0.69 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.98) with a random‐effects model. If only studies with an a priori definition for the diagnosis of pneumonia were included (Cuschieri 1985; Davies 1993; Garnett 1996; Norris 2001; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Yeager 1987), then adding a neuraxial block to general anaesthesia reduced the risk of pneumonia (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.00). For the effect of neuraxial blockade on the risk of pneumonia by type of neuraxial block, the RR was 0.90 (95% CI 0.31 to 2.62) for spinal anaesthesia (White 1980), 5.5 (95% CI 0.28 to 107.78) for lumbar epidural analgesia (Boylan 1998), 0.64 (95% CI 0.17 to 2.47) for thoracic epidural analgesia (Cuschieri 1985; Davies 1993; Norris 2001) and 0.69 (95% CI 0.45 to 1.06) when lumbar or thoracic epidural analgesia could be used (Garnett 1996; Park 2001; Peyton 2003; Yeager 1987). All studies for this comparison included a local anaesthetic in the neuraxial block. No correlation was noted between the effect size (RR) and the mean age of participants included in the studies. A summary of the new findings is provided in Table 2.

2. Summary of new findings.

| Neuraxial blockade compared with general anaesthesia for perioperative mortality, myocardial infarction or chest infection | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients of any age requiring surgery Settings: in‐hospital or ambulatory surgery Intervention: neuraxial blockade (RA) Comparison: general anaesthesia (GA) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| General anaesthesia (GA) | Neuraxial blockade (RA) | |||||

| RA versus GA: mortality Follow‐up: 30 days | Study population | RR 0.71 (0.53 to 0.94) | 3006 (20 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 79 per 1000 | 56 per 1000 (42 to 74) | |||||

| Low‐risk population | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (11 to 19) | |||||

| High‐risk population | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 71 per 1000 (53 to 94) | |||||

| RA versus GA: myocardial infarction Follow‐up: 30 days | Study population | RR 1.17 (0.57 to 2.37) | 849 (six studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 34 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (19 to 81) | |||||

| Low‐risk population | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 23 per 1000 (11 to 47) | |||||

| High‐risk population | ||||||

| 60 per 1000 | 70 per 1000 (34 to 142) | |||||

| RA versus GA: pneumonia Follow‐up: 30 days | Study population | RR 0.45 (0.26 to 0.79) | 400 (five studies2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,3,4 | ||

| 167 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (43 to 132) | |||||

| Low‐risk population | ||||||

| 40 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (10 to 32) | |||||

| High‐risk population | ||||||

| 200 per 1000 | 90 per 1000 (52 to 158) | |||||

| RA added to GA versus GA: mortality Follow‐up: 30 days | Study population | RR 1.07 (0.76 to 1.51) | 3228 (18 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 38 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 (29 to 57) | |||||

| Low‐risk population | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 21 per 1000 (15 to 30) | |||||

| High‐risk population | ||||||

| 60 per 1000 | 64 per 1000 (46 to 91) | |||||

| RA added to GA versus GA: myocardial infarction Follow‐up: 30 days | Study population | RR 0.69 (0.44 to 1.09) | 1580 (eight studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 57 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (25 to 62) | |||||

| Low‐risk population | ||||||

| 20 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (nine to 22) | |||||

| High‐risk population | ||||||

| 80 per 1000 | 55 per 1000 (35 to 87) | |||||

| RA added to GA versus GA: pneumonia Follow‐up: 30 days | Study population | RR 0.74 (0.53 to 1.03) | 2433 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 95 per 1000 | 70 per 1000 (50 to 98) | |||||

| Low‐risk population | ||||||

| 40 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (21 to 41) | |||||

| High‐risk population | ||||||

| 120 per 1000 | 89 per 1000 (64 to 124) | |||||

| *The assumed risk is based on the mean control group risk across studies. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; RA: Regional anaesthesia; GA: General anaesthesia. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

| 1Blinding. 2For the comparison RA versus GA, outcome pneumonia, studies were published between 1981 and 1987. 3Classical fail‐safe number = three. 4RR < 0.5. | ||||||

Adverse events

No serious adverse events were reported. The quality score for the reporting of complications related to neuraxial blockade was nine (median) (four to 12) (range) of a possible maximal score of 14.

Grade of evidence

The quality of the evidence was rated as moderate for all six comparisons (Table 2). Risk of bias introduced by study design was the reason for downgrading the quality from high to moderate, with the absence of blinding of outcome assessors being the most serious potentially avoidable concern. For the effect on pneumonia of the comparison of neuraxial blockade versus general anaesthesia, the small fail‐safe number (possibility of publication bias) was compensated for by the large (< 0.5) effect size.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Compared with general anaesthesia, neuraxial blockade reduced the mortality rate by approximately 2.5% (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.95; I2 = 0%) (Figure 2) and the risk of perioperative pneumonia (RR 0.44, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.73; I2 = 0%) (Figure 3). Adding a neuraxial block to general anaesthesia may reduce the incidence of pneumonia (adjusted RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.98); however, this is less conclusive, as the results varied depending on whether the effect size was adjusted for a possible publication bias. We decided to use only random‐effects models regardless of the amount of heterogeneity, as we wanted to reduce the possibility of finding an effect where there was none. When heterogeneity is present, a random‐effects model will usually widen the confidence interval. The only comparison in which we saw statistical heterogeneity was the effect on the risk of pneumonia when a neuraxial block was added to general anaesthesia compared with the use of general anaesthesia alone (I2 = 9%). If data were pooled with a fixed‐effect model, then adding a neuraxial block to general anaesthesia reduced the incidence of pneumonia (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.98), whereas no effect was detected if data were pooled with a random‐effects model (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.03). However, when we included only the studies for which an a priori definition for the diagnosis of pneumonia was reported, the addition of neuraxial blockade to general anaesthesia reduced the risk of pneumonia regardless of the model used. None of the interventions (neuraxial blockade compared with general anaesthesia or neuraxial blockade added to general anaesthesia vs general anaesthesia alone) reduced the risk of myocardial infarction (Figure 4), but the power to detect a 25% risk reduction from the addition of an epidural to general anaesthesia was only 0.25 (α = 0.05, two‐sided test).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

When deciding which intervention to choose for a patient, one has to balance the benefits versus the risks. Although many studies provided an appropriate description of the techniques used, a clear mention of the presence or absence of complications related to the techniques with an adequate duration of follow‐up was lacking in many of the reports (median Stojadinovic's score nine/14). There is no doubt for the authors of this overview that complications will need to be evaluated in future trials. Currently, we have to rely on the data provided by the most recent large prospective studies to estimate the incidence of complications related to neuraxial blockade.

Quality of the evidence

The results of this overview are based on nine Cochrane reviews. The 40 studies retained for analysis are of good quality except for two criteria. First, blinding usually was not used in these studies. Given the potentially serious (although rare) side effects that can be associated with the insertion of an epidural catheter, many clinicians would consider insertion of an epidural catheter to be unethical if it is not used to provide neuraxial blockade. Some authors have tried to insert a "sham" catheter subcutaneously to circumvent this problem. Also, the need to administer opioids both epidurally and systemically would require extra vigilance for side effects. For the comparison of neuraxial blockade versus general anaesthesia, blinding of participants is not feasible and blinding of study personnel is unrealistic, at least for the intraoperative and immediate postanaesthetic periods.

Second, many of our studies suffered from the absence of reporting of side effects of neuraxial blocks, which resulted in degrading of the quality of the studies. Our goal was to invite the trial authors to make a clear statement on the complications of the techniques that they were studying.

Potential biases in the overview process

Using systematic reviews to find relevant studies to answer a question could be considered an unusual technique, but we do not think that this led us to "biased" results. First, all of the included systematic reviews used very comprehensive search strategies. Second, by using Duval and Tweedie's trim and fill analysis, we were able to quantify the effect sizes while taking any potential publication bias into account. Publication bias occurs when medical journals publish more studies favouring one intervention than studies favouring another one or a placebo. Publication bias would be particularly frequent for studies with a small sample size. When no publication bias is noted, if a graph is constructed with the standard error or the precision (one/standard error) on the y‐axis and the logarithm of the odds ratio on the x‐axis, then studies should be equally distributed on both sides of a vertical line passing through the effect size found (log odds ratio), and the entire graph should have the shape of a reversed funnel. Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill analysis corrects the asymmetry by removing extremely small studies from the positive side (recomputing the effect size at each iteration until the funnel plot is symmetrical around the new effect size). The algorithm then adds the original studies back into the analysis and imputes a mirror image for each. The latter step does not modify the “new effect size” but corrects the variance that was falsely reduced by the first step. Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill analysis yields an estimate of what would be the effect size (odds ratio, risk ratio, etc.) if no publication bias was present (Borenstein 2009).

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

In their meta‐analysis published in 2000, Rodgers et al. (Rodgers 2000) concluded that neuraxial blockade reduced the overall 30‐day mortality by approximately one‐third and that this would apply to trials in which neuraxial blockade was combined with general anaesthesia, as well as to trials in which neuraxial blockade was used alone. We, on the other hand, demonstrated that these two interventions are not equivalent (I2 for heterogeneity between the two interventions = 69%) (Figure 2). Using a neuraxial block as the sole anaesthetic technique reduced the 30‐day mortality rate, but adding a central neuraxial block to general anaesthesia did not have this effect.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The findings of the present overview suggest that, compared with general anaesthesia, neuraxial block may reduce the 30‐day mortality rate (level of evidence: moderate) for adults undergoing a procedure with intermediate to high cardiac risk (peripheral vascular, intraperitoneal, orthopaedic and prostate surgery). The magnitude of this effect requires further exploration, as the overall quality of the included trials was moderate.

Implications for research.

Large high‐quality trials will be required to confirm or refute our results on effects on the mortality rate of using a neuraxial block as opposed to general anaesthesia. A larger sample size is required before any conclusions can be drawn regarding effects on the risk of myocardial infarction of adding an epidural to general anaesthesia. These trials should include appropriate follow‐up and descriptions of side effects to allow the reader to balance the risks and benefits of each technique.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 May 2016 | Amended | Co‐publication cited in 'Other published versions of this review' |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 9, 2012 Review first published: Issue 1, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 27 January 2014 | Amended | Formatting problem sorted out in summary of new findings table |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr Karen Hovhannisyan, Trials Search Co‐ordinator for the Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group (CARG), for designing the search, and the University of Montreal for providing access to electronic databases and major medical journals. We also thank Dr Stephan Schwarz for providing translations of the two German articles in our systematic overview, Dr Helen Handoll for providing translations of some Japanese and Italian articles and Dr Mina Nishimori for granting us access to her data extraction sheets. Finally, we are indebted to Drs Mark Neuman (content editor), Marialena Trivella (statistical editor) and Lorne Becker, Denise Thompson, Jørn Wetterselv and Mina Nishimori (peer reviewers) for their help and editorial advice provided during the preparation of this overview.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Summary of major findings of the reviews included in this overview

| Authors | Date assessed as up‐to‐date | Number of studies/Number of participants | Population | Interventions and comparison interventions |

Major findings |

| Neuraxial blockade versus general anaesthesia | |||||

| Afolabi 2006 | 14 August 2006 | 16 1586 |

Pregnant women Caesarean section for any indication |

Epidural anaesthesia or Spinal anaesthesia versus General anaesthesia |

Neuraxial blockade reduces:

General anaesthesia:

|

| Barbosa 2010 | 9 June 2008 | Four 696 |

Adults Lower limb revascularization |

Epidural anaesthesia or Spinal anaesthesia versus General anaesthesia |

No difference:

Neuraxial blockade reduces:

|

| Craven 2003 | 31 March 2003 | Three 108 |

Preterm infants Inguinal herniorrhaphy |

Spinal anaesthesia versus General anaesthesia |

No difference in:

Excluding infants who received preoperative sedatives, neuraxial blockade:

|

| Parker 2004 | 10 June 2004 | 22 2567 |

Adults Hip fracture |

Epidural anaesthesia or Spinal anaesthesia versus General anaesthesia |

Neuraxial blockade:

|

| Neuraxial blockade added to general anaesthesia | |||||

| Choi 2003 | 13 May 2003 | 13 606 |

Adults Hip or knee replacement |

Epidural analgesia versus Systemic analgesia |

Neuraxial blockade:

|

| Cyna 2008 | 13 April 2008 | 10 721 |

Male children Circumcision |

Caudal epidural block versus Systemic analgesia or Dorsal nerve penile block |

Neuraxial blockade versus parenteral analgesia.

Neuraxial blockade versus dorsal nerve penile block.

Neuraxial blockade versus rectal or intravenous analgesia.

|

| Jorgensen 2000 | 31 August 2000 | 22 1023 |

Adults Abdominal surgery |

Epidural local anaesthetic versus Systemic opioids or Epidural opioids |

Substantial heterogeneity Neuraxial blockade with local anaesthetic versus systemic opioids:

Neuraxial blockade with local anaesthetic versus epidural opioid:

|

| Nishimori 2012 | 16 January 2011 | 13 1224 |

Adults Elective open abdominal aortic surgery |

Epidural analgesia versus Systemic opioid–based pain relief |

Neuraxial blockade (especially thoracic epidural):

|

| Werawatganon 2005 | 13 October 2004 | Nine 711 |

Adults Intra‐abdominal surgery |

Epidural analgesia versus Patient‐controlled analgesia with intravenous opioids |

Neuraxial blockade:

|

MD: mean difference; SMD: standardized mean difference.

Appendix 2. Characteristics of included studies

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 57 patients undergoing emergent femoral fracture repair (< 72 hours) |

| Interventions |

Epidural anaesthesia (n = 28): test dose 5 mL followed by 9 to 21 mL of 2% prilocaine with epinephrine 5 mcg/mL through a catheter inserted at L3‐L4 or L4‐L5, then half the volume of 0.5% bupivacaine or prilocaine with epinephrine 75 minutes later. The catheter was removed at the end of the surgery General anaesthesia (n = 29): thiopental 3 to 4 mg/kg, succinylcholine, nitrous oxide, halothane and succinylcholine infusion |

| Outcomes | Mortality: One participant in the epidural group died on postoperative day one; three (group unspecified) died around five months after the surgery, for a total of four/57 deaths at one year Pneumonia: no a priori definition (x‐ray performed preoperatively and treated after the surgery) |

| Notes | Dextran and mobilization at postoperative day one used as thromboprophylaxis. No mention about presence/absence of complications related to regional or general anaesthesia |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomly allocated: no details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unlikely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessors (for POCD) were blinded to the anaesthetic technique |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Four participants lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Mortality given up to one year (although exact group not given). Presence/absence of complications related to the anaesthetic techniques not reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Higher proportion of Ischaemic heart disease (18 vs 11) and of cerebrovascular disease (four vs two) in the epidural group |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 40 patients undergoing emergent femoral fracture repair (< 48 hours) |

| Interventions |

Spinal anaesthesia (n = 20): 3 mL of 0.75% bupivacaine at L3‐L4 General anaesthesia (n = 20): diazepam, fentanyl, nitrous oxide and pancuronium bromide |

| Outcomes | Mortality: The two deaths reported occurred early Pneumonia: no a priori criteria mentioned; diagnostic criteria unspecified |

| Notes | Early ambulation, no other thromboprophylaxis |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomly allocated: no details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unlikely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High risk | Assessor (POCD) blinded to the anaesthetic technique used. Unspecified for the other outcomes |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | No dropout or failed block reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear whether results apply to all enrolled participants |

| Other bias | Low risk | Groups well balanced for ASA physical status |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 423 patients undergoing elective peripheral vascular surgery (femoral or distal) |

| Interventions |

Spinal anaesthesia (n = 107): 16 to 20 mg of hyperbaric 1% tetracaine with 3 to 5 mg of phenylephrine at L3‐L4 or L4‐L5 Epidural anaesthesia (n = 96): at L2‐3 or L3‐4; 2% lidocaine followed by 0.5% bupivacaine to maintain a sensory level between T8 and T10. Epidural morphine was administered for the first 12 to 24 hours in 40% of participants General anaesthesia (n = 112): thiopental 2 to 4 mg/kg, fentanyl, succinylcholine, nitrous oxide, isoflurane or enflurane and vecuronium |

| Outcomes | Mortality: death occurring during the participant's hospitalization Myocardial infarction: ECG after surgery and daily for four days; CK every eight hours for 24 hours, then daily for three days; defined as new Q‐waves > 0.03 seconds with ↑ ST ≥ 1 mm in ≥ two leads or new ↓ ST ≥ 1 mm in ≥ two leads with ↑ CPK with > 5% MB fraction 68% (13/19) were silent, all occurred within four days. The study authors mention in the discussion that the rate of myocardial infarction might have been overestimated in light of the underlying pathology (CK‐MB elevation) Mortality was defined as cardiac death occurring during postoperative hospitalization |

| Notes | Unfractionated heparin 5000 units every 12 hours until ambulation and oral aspirin 81 mg daily until discharge thereafter. Presence/absence of complications from the anaesthetic technique are not mentioned |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization was done by computer program |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Placed in sealed envelopes. The envelopes were not opened until after eligible patients consented to participate in the study |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unlikely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Outcome assessor (cardiologist) blinded to the anaesthetic technique used for myocardial infarction |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Comment: no missing outcome data reported in Bode 1996 (for 423 participants until hospital discharge or death). Missing data (surgical outcome) are not relevant to this overview |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | 423 participants selected from 705 consecutive eligible patients. Comment: no missing outcome data reported in Bode 1996 (for 423 participants until hospital discharge or death). Data analysed in intention‐to‐treat and per‐protocol. 32 failed blocks. Presence/absence of complications related to the anaesthetic techniques not reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | From the review: "The Pierce 1997 was a post‐hoc analysis of the population recruited in Bode 1996 publication. Pierce presented graft function at 30 days in 264 of the 423 participants recruited into the original article." But for this overview, this does not apply. Slighlty less prior CHF (18.8% vs 27.3% and 28%) in the general anaesthesia group; otherwise, groups well matched |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia added to general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 124 patients undergoing elective abdominal aortic surgery |

| Interventions |

General anaesthesia in both groups: midazolam, fentanyl, nitrous oxide, isoflurane and vecuronium Thoracic epidural anaesthesia (n = 59): T6‐T7 or T7‐T8 with 3 mL of 1.5% lidocaine with epinephrine 5 mcg/mL, followed (at completion of surgery) by 0.1 mL/kg of 0.125% bupivacaine with fentanyl 10 mcg/mL and an infusion adjusted for VAS scores ≦ three/10 (rest or movement) for 48 hours Morphine IVPCA (n = 65): adjusted for VAS scores ≦ three/10 (rest) for 48 hours |

| Outcomes | Mortality: during hospitalization Myocardial infarction: new Q‐waves ≧ 0.04 seconds' duration and ↓ ≧ 1 mm on the 12‐lead ECG, or CK‐MB ≧ 50 IU/L. Two‐lead Holter for 24 hours (validated by a cardiologist) |

| Notes | Heparin 0.5 mg/kg before infrarenal aortic cross‐clamping |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized: no details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unlikely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Four with TEA and six with IV PCA excluded because of failure of Holter monitoring or epidural analgesia, or because of the use of analgesia not included in the protocol. One non‐Q myocardial infarction among the excluded TEA participants; no other complications in the excluded participants. This participant was included in the analysis of the overview |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data entered in intention‐to‐treat analysis for this overview. Presence/absence of complications related to the anaesthetic techniques not reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Slightly fewer smokers (33% vs 46%) in the epidural group; otherwise, groups well matched |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia added to general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 40 patients undergoing elective abdominal aortic surgery |

| Interventions |

General anaesthesia in both groups: thiopental, fentanyl, nitrous oxide, isoflurane and neuromuscular blocking agents Lumbar epidural anaesthesia (n = 19): L2‐L3 or L3‐L4 with 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 5 mcg/mL, followed by 0.25% bupivacaine with morphine during the surgery and 0.125% bupivacaine with 0.1 mg/mL of morphine after the surgery adjusted for VAS scores four/10 (rest or movement) ≦ 48 hours Morphine IV PCA (n = 21) |

| Outcomes | Death: during hospitalization Myocardial infarction: no a priori definition. For the participant in the IVPCA group, MI with cardiogenic shock on the second postoperative day. For the participant in LEA, arm pain and elevated cardiac enzyme (value not provided) Pneumonia: no definition and no details (during hospitalization) |

| Notes |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Open randomized: no details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Open study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | ST depression verified by a blinded assessor |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Failure to proceed to surgery as planned led to withdrawal. Two participants in LEA discontinued because of severe pruritus: One received bupivacaine‐fentanyl and the other IV PCA with meperidine at 30 hours. Naloxone for one participant in each group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Not in intention‐to‐treat (see above). Presence/absence of complications related to the anaesthetic techniques not reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Higher blood loss (1610 mL vs 1017 mL) and longer surgical time (227 minutes vs 188 minutes) for IVPCA group |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia added to general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 90 patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery |

| Interventions |

General anaesthesia in both groups: thiopental or etomidate, sufentanil, nitrous oxide, isoflurane and vecuronium Thoracic epidural anaesthesia (n = 60): T7‐T8 or T8‐T9 with 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 5 mcg/mL, followed by 0.125% bupivacaine with sufentanil (n = 30) or morphine (n = 30) adjusted for VAS scores ≦ four at rest or six at movement for 48 hours Fentanyl infusion followed by IM injections (n = 30) |

| Outcomes | Mortality during hospitalization |

| Notes | Complications of epidural techniques recorded: no neurological sequelae |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomly assigned: no details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Not blinded to epidural or IM |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Low risk | Observer blinded to the route of administration. Sham epidural catheter on the skin, connected to an empty syringe in an infusion pump, which was covered to shield its content. The same cover was used for participants in the TEA group |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | No participant lost to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Intention‐to‐treat for this overview |

| Other bias | Low risk | Groups well balanced |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia added to general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 42 patients undergoing elective open colorectal surgery |

| Interventions |

General anaesthesia in both groups: thiopental, fentanyl, nitrous oxide, isoflurane and vecuronium Thoracic epidural anaesthesia (n = 21): T8 or T9 with 15 to 20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine for a sensory block from T4 and S5, followed by 5 mL of 0.5 bupivacaine every hour during the surgery and epidural analgesia with 0.1% bupivacaine and fentanyl 2 mcg/mL adjusted for VAS scores < five/10 at rest for up to four days after the surgery Morphine IV PCA (n = 21): adjusted for VAS scores < five/10 at rest |

| Outcomes | Mortality Myocardial infarction: no definition provided |

| Notes | Antibiotic prophylaxis, early feeding and mobilization starting the day after surgery |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Allocated at random: no details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unlikely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Data provided for all participants |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Data provided for measurements specified in the method section |

| Other bias | Low risk | Group well balanced |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 100 patients undergoing elective lower extremity revascularization |

| Interventions |

Lumbar epidural anaesthesia (n = 49): L2‐L3 or L3‐L4 with 3 mL of 1.5% lidocaine with epinephrine, followed by 7 mL of 0.75% bupivacaine through the needle and additional doses through a catheter during the surgery for sensory level at T8. Epidural fentanyl infusion for 24 hours after the surgery General anaesthesia (n = 51): with thiamylal, fentanyl, morphine, succinylcholine, tracheal lidocaine spray, nitrous oxide, enflurane and pancuronium. Morphine IV PCA after the surgery |

| Outcomes | Mortality: Data are available for zero to seven days and for zero to six months. For this overview, the zero to seven days was taken as zero to 30 days, and the difference between zero to seven and zero to six months was taken as one to six months Myocardial infarction (MI): based on preoperative 12‐lead ECG, day of surgery and on postoperative days one, two, three and seven; CK‐MB every six hours during ICU stay, then daily through postoperative day three; information on chest pain during the first seven days; autopsies/death certificates (blinded). MI diagnosed on Lipid Research Clinic, ECG according to Minnesota Code Pneumonia: defined as a new infiltrate on a chest x‐ray combined with the appearance of two of the following conditions within 24 hours of the radiological abnormality: a temperature greater than 38ºC, a leukocyte count above the normal range or the identification of a pathogen by sputum Gram stain or culture. Data not provided separately from sepsis |

| Notes | IV heparin according to the surgeon. When an infusion of IV heparin was given before the surgery, it was stopped four hours before the participant's arrival to the operating theatre. After surgery, heparin was administered to participants with diminished blood flow The trial was stopped prematurely by a monitoring committee (120 planned) on the basis of lower rate of regrafting/embolectomy in the epidural group (two vs nine) and no apparent benefit of general anaesthesia |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization was stratified (cardiac risk by the surgeon) within blocks of variable sizes arranged in random order |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Participants were randomly assigned in the operating room immediately before surgery. Allocation was done immediately before the procedure, but unclear how sequence was concealed |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Open study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Cardiologists assessing cardiac outcomes were blinded to the anaesthetic technique; all other outcomes were assessed openly |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High risk | Overall rate of missing data was 1.9% in participants assigned to the general anaesthesia regimen and 3.1% in participants assigned to epidural anaesthesia and analgesia |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Intention‐to‐treat. Presence/absence of complications related to the anaesthetic techniques not reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Group well balanced, except slightly more diabetic participants in the GA group (41% vs 29%) |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 101 patients undergoing lower limb vascular surgery |

| Interventions |

Spinal anaesthesia (n = 50): 1.4 to 1.6 mL of hyperbaric 0.5% cinchocaine with 0.1 to 0.2 mL of epinephrine 1:1000 for a sensory level ≧ T10 General anaesthesia (n =51): thiopental, fentanyl, nitrous oxide, halothane and alcuronium or pancuronium bromide |

| Outcomes | Mortality: until discharge (all those deaths occurred within 30 days) Myocardial infarction: significant myocardial Ischaemic episode defined as ST segment depression > 1.0 mm on a correctly calibrated paper; followed for occurrence of chest pain consistent with Ischaemic heart disease. Real definition of myocardial infarction not provided Pneumonia: fever plus productive sputum or chest x‐ray changes |

| Notes | Heparin 5000 U IV before vascular clamping |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomly allocated: no details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unlikely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | All data are available for the outcomes retained for this overview |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The outcome data were reported adequately. |

| Other bias | Low risk | Groups well balanced for ASA physical status scores and age (67.1 vs 66.4 years of age) |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 100 patients > 80 years of age undergoing emergent femoral fracture repair (< 24 hours of admission) |

| Interventions | Lumbar epidural anaesthesia (n = 50): single shot (n = 34) or continuous (n =16) with 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine 5 mcg/mL (with 2% lidocaine in some participants) General anaesthesia (n = 50): thiopental, nitrous oxide, dextromoramide or methoxyflurane, succinylcholine or pancuronium bromide |

| Outcomes | Mortality: Data are provided for zero to 11 days (kept as zero to 30 days) and at 11 days to three months (not kept) Myocardial infarction: ECG (ECG before and after [3 hours] the surgery and at 1, 3 and 10 days). New waves compatible with necrosis |

| Notes | Early mobilization and anti‐vitamin K from third postoperative day |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Drawing" (tirage au sort) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unlikely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Data are given for all participants |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Data provided for measurements specified in the method section. Presence/absence of complications related to the anaesthetic techniques not reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | Groups well balanced for age, hypertension, abnormal ECG, vasculitis, chronic bronchitis with respiratory insufficiency, cerebrovascular accident, senility and Parkinson |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia added to general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 75 consecutive patients < 75 years of age undergoing open cholecystectomy |

| Interventions | General anaesthesia in all participants with thiopental, intravenous narcotics and inhalational agents Thoracic epidural anaesthesia (n = 25): at the lower thoracic region, with an age‐related dose of 0.5% bupivacaine and kept for 12 hours Morphine IV infusion (n = 25) or IM (n = 25) |

| Outcomes | Pneumonia: Preoperative respiratory status was established by a questionnaire, a clinical examination and chest radiography. Chest infection was defined as pyrexia, production of purulent sputum, clinical signs of infection and radiological evidence of collapse persisting for longer than 72 hours. Antibiotics were given at the discretion of the clinician involved |

| Notes | 1.5 g cefuroxime was given intravenously before skin incision H Influenzae or S pneumoniae were isolated from eight/12 participants who developed chest infection No serious complications occurred in the epidural group |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized: no other details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unlikely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Participants were assessed daily during the postoperative period by a single observer |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Unclear risk | No loss to follow‐up reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Attempts to insert the epidural catheter failed in four participants, who therefore received intermittent intramuscular morphine 10 mg as required. Data from these four participants were included in the epidural group for the purpose of analysis. The single chest infection of the TEA group developed in one of these technical failures |

| Other bias | Low risk | The groups were comparable in terms of physical characteristics, history of respiratory disease, smoking habits and duration of anaesthesia. Smokers 24/50 versus 11/25 and respiratory disease 20/50 and 11/25 (IV/IM and TEA, respectively) |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia added to general anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |

| Participants | 50 consecutive patients scheduled for elective abdominal aortic surgery |

| Interventions | General anaesthesia in all participants with thiopental, fentanyl, nitrous oxide, enflurane and pancuronium bromide Thoracic epidural analgesia (n = 25): at T9‐T10 with 2 mL of 1.5% lidocaine with epinephrine 5 mcg/mL, followed by 5 mL hourly during surgery and 0.5% bupivacaine after surgery for 72 hours IV morphine analgesia (n = 25): 2 to 5 mg/h |

| Outcomes | Death Myocardial infarction: new Q‐waves, 0.04 seconds' duration, 1 mm amplitude; or increased CPK (MB) considered to be diagnostic of myocardial damage with/without ECG changes; or recent myocardial infarction at autopsy. CK‐MB die for three days Pneumonia: infiltatres on chest x‐ray, plus two of temperature > 38ºC, raised white blood cell count or positive sputum. Chest x‐ray for three days |

| Notes |

Risk of bias table

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomized: no details |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unclear |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | High risk | Unlikely |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Unclear risk | Independent anaesthetist |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Low risk | Data provided for all participants |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | One failed epidural kept in intention‐to‐treat. Presence/absence of complications related to the anaesthetic techniques not reported |

| Other bias | High risk | Groups well balanced for age, ASA physical status and preoperative coexisting diseases except chronic airways disease (five/25 vs 16/25 for control and TEA, respectively). |

| Methods | Regional anaesthesia versus general anaesthesia |