Abstract

Background

Evidence from animal models and observational studies in humans has suggested that there is an inverse relationship between dietary intake of omega 3 long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) and risk of developing age‐related macular degeneration (AMD) or progression to advanced AMD.

Objectives

To review the evidence that increasing the levels of omega 3 LCPUFA in the diet (either by eating more foods rich in omega 3 or by taking nutritional supplements) prevents AMD or slows the progression of AMD.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Trials Register) (2015, Issue 1), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to February 2015), EMBASE (January 1980 to February 2015), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS) (January 1982 to February 2015), the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 2 February 2015.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) where increased dietary intake of omega 3 LCPUFA was compared to placebo or no intervention with the aim of preventing the development of AMD, or slowing its progression.

Data collection and analysis

Both authors independently selected studies, assessed them for risk of bias and extracted data. One author entered data into RevMan 5 and the other author checked the data entry. We conducted a meta‐analysis for one primary outcome, progression of AMD, using a fixed‐effect inverse variance model.

Main results

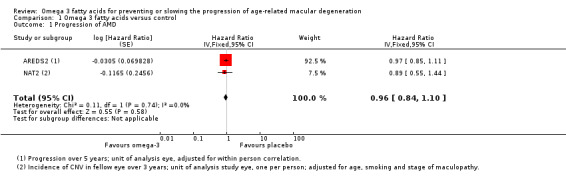

We included two RCTs in this review, in which 2343 participants with AMD were randomised to receive either omega 3 fatty acid supplements or a placebo. The trials, which had a low risk of bias, were conducted in the USA and France. Overall, there was no evidence that people who took omega 3 fatty acid supplements were at decreased (or increased risk) of progression to advanced AMD (pooled hazard ratio (HR) 0.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.84 to 1.10, high quality evidence). Similarly, people taking these supplements were no more (or less) likely to lose 15 or more letters of visual acuity (USA study HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.10; French study at 36 months risk ratio (RR) 1.25, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.26, participants = 230). The number of adverse events was similar in the intervention and placebo groups (USA study participants with one or more serious adverse event RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.09, participants = 2080; French study total adverse events RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.13, participants = 263).

Authors' conclusions

This review found that omega 3 LCPUFA supplementation in people with AMD for periods up to five years does not reduce the risk of progression to advanced AMD or the development of moderate to severe visual loss. No published randomised trials were identified on dietary omega 3 fatty acids for primary prevention of AMD. Currently available evidence does not support increasing dietary intake of omega 3 LCPUFA for the explicit purpose of preventing or slowing the progression of AMD.

Keywords: Humans; Disease Progression; Fatty Acids, Omega‐3; Fatty Acids, Omega‐3/adverse effects; Fatty Acids, Omega‐3/therapeutic use; Macular Degeneration; Macular Degeneration/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Omega 3 fatty acids for preventing and slowing the progression of age‐related macular degeneration

Review question We asked the question whether increased dietary intake of omega 3 fatty acids prevented or slowed the progression of age‐related macular degeneration.

Background Age‐related macular degeneration (AMD) is an eye condition that affects the central area of the retina (light‐sensitive tissue at the back of the eye). AMD is associated with a loss of detailed vision and adversely affects tasks such as reading, driving and face recognition. In the absence of a cure, there has been considerable interest in the role of modifiable risk factors to prevent or slow down the progression of AMD. Evidence from population studies suggests that people who have a diet with relatively high levels of omega 3 fatty acids (such as those derived from fish oils) are less likely to develop AMD.

Study characteristics We searched for studies up to 2 February 2015. We identified two trials with a total of 2343 participants. The trials were conducted in the USA and France and investigated the use of fish oil supplements in people with AMD who were at high risk of progressing to advanced disease. We judged the studies to be at low risk of bias. One study was funded by government grants and the other study was funded by the manufacturer of the dietary supplement.

Key results These studies found that omega 3 supplementation for periods up to five years did not reduce the rate of progression to advanced AMD or reduce significant visual loss compared to a placebo. The incidence of adverse effects was similar in the intervention and placebo groups.

Quality of the evidence We judged the quality of the evidence on rate of progression to AMD to be high, and the quality of the evidence for other outcomes to be moderate because the estimates were imprecise.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Omega 3 fatty acids compared to placebo for slowing the progression of age‐related macular degeneration.

| Omega 3 fatty acids compared to placebo for slowing the progression of age‐related macular degeneration | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with AMD Settings: community Intervention: omega 3 fatty acids Comparison: no omega 3 fatty acids (placebo) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No omega 3 fatty acids (placebo) | Omega 3 fatty acids | |||||

| Loss of 3 or more lines of VA at 24 months | 100 per 1000 | 114 per 1000 (53 to 245) | RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.45 | 236 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Loss of 3 or more lines of VA at 36 months | 150 per 1000 | 187 per 1000 (104 to 339) | RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.26) | 230 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Incidence of CNV at 24 months | 100 per 1000 | 106 per 1000 (47 to 240) | RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.40 | 224 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Incidence of CNV at 36 months | 150 per 1000 | 168 per 1000 (80 to 357) | RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.38 | 195 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Progression of AMD over 5 years | 300 per 1000 | 290 per 1000 (259 to 325) | HR 0.96 (0.84 to 1.1) | 2343 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | |

| Adverse effects | 500 per 1000 | 505 per 1000 (470 to 545) | RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.09 | 2343 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | AREDS2 reported participants with one or more serious adverse events (AE). NAT‐2 reported total AE including treatment emergent and serious non‐ocular events |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded for imprecision

Background

Description of the condition

Age‐related macular degeneration (AMD) is the most common cause of blindness and visual impairment in developed countries, accounting for over 50% of blind and partially sighted certifications in the UK (Bunce 2010). Since the disease predominantly affects individuals aged 55 years and over, its prevalence continues to rise as the population is living longer. AMD is characterised by degenerative changes within the macula, the central area of the retina responsible for detailed vision and colour perception (Lim 2012). The early stage of AMD is associated with an accumulation of small focal yellowish deposits (drusen) under the retinal pigment epithelium, often with an associated pigmentary disturbance. At this stage the patient is generally asymptomatic, however, as the disease progresses large focal areas of retinal pigment epithelial cell loss can occur, referred to as geographic atrophy, which leads to a progressive worsening of central vision. In approximately 10% of cases, an acute neovascular response arises under the retina, with associated blurring or distortion of vision. If untreated, the resulting haemorrhagic and exudative pathology disrupts normal retinal anatomy, eventually leading to the formation of a dense fibrous scar. When both eyes are affected, late AMD causes significant visual impairment, with difficulties in reading, driving and recognising faces. It can, therefore, severely impact on vision‐related quality of life. The estimated prevalence of late AMD in populations of European ancestry is 1.4% at age 70 years, increasing to 5.6% at 80 and 20.1% at 90 years of age (Rudnicka 2012). In the UK, the annual incidence of late AMD in the population aged 50 years and above is 4.1 per 1000 women and 2.6 per 1000 men (Owen 2012).

There is currently no cure for AMD. Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors that are injected directly into the vitreous humour of the eye can stabilise vision in neovascular AMD, however no effective treatment is available for geographic atrophy. In the absence of a cure, research has focused on preventing or slowing the progression of AMD through the control of modifiable risk factors, for example smoking or dietary modification (including the use of nutritional supplements).

Description of the intervention

This review considers the evidence for the role of omega 3 fatty acids in the primary prevention and treatment of AMD. Fatty acids are divided into three broad categories, saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated. Although humans can synthesise saturated and monounsaturated fats, they do not have the enzyme systems required to synthesise polyunsaturated fatty acids and therefore dietary sources are essential. Long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) are classified according to their chemical structure. They have a methyl group at one end of the molecule and a carboxyl group at the other, separated by a chain of 18 or more carbon atoms that contains two or more double bonds. The n‐3 variety of LCPUFA (designated ω‐3 or omega 3) has a double bond positioned three carbon atoms from the methyl end of the molecule. Omega 3 LCPUFA are obtained principally from dietary sources, however they can be synthesised from the short‐chain omega 3 fatty acid alpha linolenic acid, although endogenous synthesis in humans is limited (Burdge 2002).

The omega 3 LCPUFA docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is present in high concentrations in retinal photoreceptors and is therefore essential for visual function. Although a diet rich in oily fish, eggs, nuts and particular vegetable oils provides a plentiful supply of omega 3 fatty acids, there has been a great deal of interest in the health benefits of omega 3 supplementation, and commercially available supplements in the form of oils and capsules are widely available. Capsules typically contain a mixture of DHA and its precursor eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), often in combination with antioxidant vitamins and minerals.

How the intervention might work

There is a plausible biological rationale for increasing omega 3 LCPUFA in AMD. DHA accounts for 50% to 60% of the total fatty acid content of the outer segments of photoreceptors. The constant turnover of outer segment membranes requires a continuous dietary supply of DHA, or its precursors, and a deficiency may predispose a person to the development of AMD. Omega 3 LCPUFA may also confer protection against the oxidative, inflammatory and vasogenic processes that play a key role in the pathogenesis of AMD (Kishan 2011; SanGiovanni 2005). In a mouse model that develops a range of AMD‐like retinal lesions, progression of the disease was slowed and in some cases reversed in a group of mice fed on a diet rich in DHA and EPA (Tuo 2009). The protective effect of omega 3 LCPUFA was associated with a reduction in pro‐inflammatory mediators and an increase in the levels of anti‐inflammatory metabolites. An EPA rich diet has also been shown to suppress experimental choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) and CNV‐related inflammatory molecules both in vitro and in vivo (Koto 2007).

Epidemiological studies in humans have provided some evidence that consumption of fish and foods rich in omega 3 LCPUFA could reduce the risk of developing AMD (Chong 2009; Christen 2011; Hodge 2006; Tan 2009). Similarly, a nested cohort study within the Age‐Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) found that participants at moderate to high risk of progressing to late AMD who reported the highest consumption of omega 3 LCPUFA were 30% less likely to develop geographic atrophy and neovascular AMD when compared to those reporting the lowest consumption (SanGiovanni 2009).

Why it is important to do this review

The high prevalence of AMD and the limited availability of effective treatments for the majority of sufferers highlights the need to search for new treatment strategies to prevent or slow the progression of the disease. There is significant interest in the role of diet and nutritional supplementation in AMD. There is evidence that antioxidant vitamins (beta‐carotene, vitamin C and vitamin E) and zinc supplementation slow down the progression to advanced AMD (Evans 2012b), but there is no evidence to support the use of these supplements in primary prevention (Evans 2012a). Although observational studies have suggested a protective role for omega 3 LCPUFA in the prevention and treatment of AMD, these results may be confounded by other dietary or lifestyle factors. Therefore, a systematic review of randomised controlled trials that examines the effect of increasing dietary intake of omega 3 LCPUFA in AMD was needed. The review considered evidence for both atrophic and neovascular AMD.

Objectives

To review the evidence that increasing the levels of omega 3 LCPUFA in the diet (either by eating more foods rich in omega 3 or by taking nutritional supplements) prevents or slows the progression of AMD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) where increased dietary intake of omega 3 fatty acids was compared to placebo or no intervention.

Types of participants

People from the general population with or without AMD. The definition of AMD was taken as defined by study investigators (for example using a standardised grading scheme, or AMD leading to a reduction in visual acuity).

Types of interventions

Any type and any dose of omega 3 fatty acids, either as fish oil capsules or dietary manipulation (for example increased consumption of oily fish). The intervention could be delivered either as monotherapy or in combination with other measures, where the study design allowed for the effect of the omega 3 treatment to be isolated. We imposed no restriction on the duration of treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

We defined the primary outcomes as follows:

risk of developing incident AMD or new visual loss attributed to AMD; and

risk of progression of AMD in people previously diagnosed with the disease.

Secondary outcomes

We defined the secondary outcomes as follows:

quality of life; and

any adverse outcomes reported.

We assessed primary and secondary outcomes as reported by study authors either in the short term (less than two years) or following a longer‐term intervention (more than two years).

We used the following definitions in the review.

AMD: there are a number of internationally recognised classification systems that rely on photographic grading of fundus images, e.g. Wisconsin Age‐related Maculopathy Grading System (Klein 1991) or the Age‐Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) Classification System (AREDS 1999) which encompasses five categories of increasing severity from 'early' to 'advanced' AMD. However, study‐specific definitions may also be used, e.g. following ophthalmoscopic examination of the retina or confirmation from medical records of participant self reporting of AMD.

AMD progression: may be defined by a change in severity based on fundus appearance or progressive visual loss due to AMD.

Visual loss: any well‐defined outcome based on visual acuity measured using a standardised measurement technique.

Quality of life: any validated measurement scale which aims to measure vision functioning or vision‐specific quality of life.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group Trials Register) (2015, Issue 1), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE (January 1946 to February 2015), EMBASE (January 1980 to February 2015), Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature Database (LILACS) (January 1982 to February 2015), the ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch), ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en). We did not use any date or language restrictions in the electronic searches for trials. We last searched the electronic databases on 2 February 2015.

See: Appendices for details of search strategies for CENTRAL (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Appendix 3), LILACS (Appendix 4), mRCT (Appendix 5), ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 6) and the ICTRP (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We reviewed the reference list of included studies to identify additional trials for this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We screened the titles and abstracts of articles retrieved by the searches independently. We obtained full‐text copies of articles that definitely or potentially met the inclusion criteria. We independently reviewed these and selected studies according to the definitions in the Criteria for considering studies for this review. We documented reasons for excluding studies at this stage and resolved any disagreements by discussion.

We wrote to authors of included studies to ask if they were aware of any published or unpublished studies on omega 3 acids in relation to AMD.

Data extraction and management

We independently extracted data from eligible studies using a standardised form developed by the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group. We compared the results and resolved any discrepancies by discussion. One author cut and pasted the data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014) and the other checked that this was done correctly.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the 'risk of bias' assessment tool developed by Cochrane, described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) to assess the quality of included studies. The tool uses the following criteria.

Sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding (masking).

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting.

Other sources of bias.

We performed the 'risk of bias' assessment independently and resolved any discrepancies by discussion.

Measures of treatment effect

In general for binary outcomes we used the risk ratio (RR). For the analysis of progression to advanced AMD, the available data were reported from Cox proportional hazard models and therefore for this outcome the results were expressed as a hazard ratio.

Unit of analysis issues

The majority of studies in this area are parallel‐group RCTs. Cluster randomisation (where individuals are randomised in groups) and cross‐over trials are unlikely to be used to investigate the role of omega 3 LCPUFA in AMD but will be considered in the future if these studies become available.

We analysed the results by person since the individual is the unit of randomisation (as the intervention is applied to the individual, not the eye).

Dealing with missing data

The data included in this review represented an 'available case analysis'. This makes the assumption that data are missing at random. We recorded the amount of missing data and reasons for exclusions and attrition, where available, and contacted investigators for clarification. We did not impute missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity by examining the forest plot, along with the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic.

Assessment of reporting biases

There were insufficient numbers of studies to carry out a funnel plot analysis to investigate the relationship between treatment effect and study size.

Data synthesis

For data on progression of AMD, log hazard ratios and standard errors were obtained from Cox proportional hazards regression models. These results were combined using the generic inverse‐variance method and since only two trials were available for analysis, a fixed‐effect model was used.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Insufficient data were available to perform any subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

No sensitivity analysis was planned.

Results

Description of studies

See: the Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables for more information.

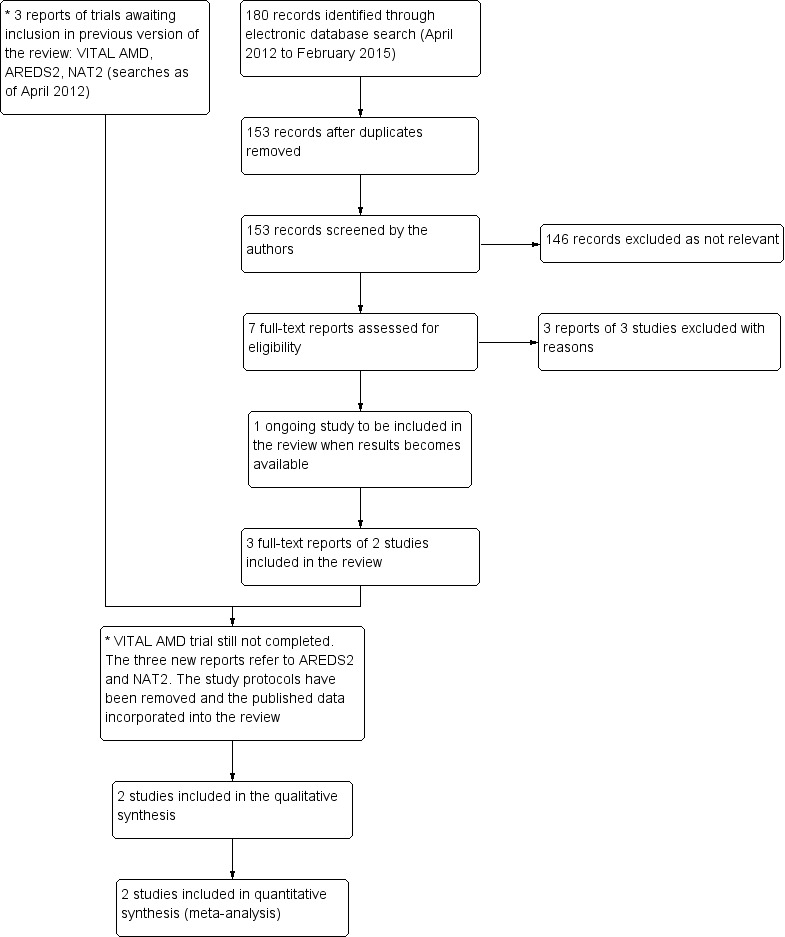

Results of the search

The electronic searches run in January 2012 yielded a total of 337 references. The Trials Search Co‐ordinator scanned the search results, removed duplicates and removed 135 references which were not relevant to the scope of the review. We screened the remaining 116 reports to identify potentially relevant studies. We obtained full‐text copies of four studies and excluded them after reading the full reports (Feher 2005; Huang 2008; Johnson 2008; Scorolli 2002). We also excluded two studies after reading their unpublished reports (NCT01258335; OPAL). We identified two ongoing studies (AREDS2; VITAL‐AMD) and another completed trial (ISRCTN98246501/NAT2) was awaiting publication. These studies were to be assessed for inclusion in the review when data became available.

An update search run in February 2015 identified a further 180 references (Figure 1). After de‐duplication we screened 153 references and discarded 146 as not being relevant to the scope of the review. We obtained seven full‐text reports for potential inclusion in the review. After assessment we included three reports of two trials (AREDS2; NAT2) and excluded three trials (Arnold 2013; García Layana 2013; Ziegler 2013). We have identified an ongoing trial (NCT02264938) and will assess this trial when results become available. In the previous version of this review there were three trials awaiting assessment, which would be included when data became available. The VITAL‐AMD trial has not yet been completed and is still classed as ongoing. The study protocols for AREDS2 and NAT2 have been removed from the review as the results of these trials have now been published and incorporated into the review as the two new included studies.

1.

Results from searching for studies for inclusion in the review.

Included studies

Below is a summary of the two trials included in this review. See Characteristics of included studies for detailed information on individual trials.

Types of participants

Both trials included participants at high risk of developing advanced AMD; with either bilateral large drusen or large drusen in one eye and advanced AMD in the fellow eye (AREDS2), or early AMD in the study eye and CNV in the fellow eye (NAT2). The mean age for people participating in the trials was 74 years. On average, slightly more women than men were recruited (mean percentage that were female 56%). People taking part in the trials were either recruited from a single hospital clinic (NAT2), recruited from specialist retinal clinics or were volunteers from the general population (AREDS2).

Types of intervention

AREDS2 compared a daily dose of 650 mg EPA and 350 mg DHA to placebo. All participants were additionally instructed to take the original AREDS formula of antioxidant vitamins and zinc (AREDS 1999) or were entered into a secondary randomisation to investigate the effects of variations of this formula. NAT2 compared 840 mg DHA and 270 mg EPA daily to placebo (olive oil capsules). In AREDS2 the duration of supplementation was five years and for NAT2 participants were supplemented for three years.

Types of outcome measures

The main outcome measures for both trials were the development of advanced AMD and loss of visual acuity corresponding to 15 letters or more from baseline. For AREDS2 advanced AMD was defined as central geographical atrophy (GA) or choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) and was assessed by grading stereoscopic fundus images using masked graders. For NAT2 the AMD outcome was the occurrence of CNV in the study eye (confirmed by angiography). In both trials visual acuity was measured using a standard ETDRS chart (15 letters corresponds to a loss of 3 lines on the chart and is equivalent to a doubling of the visual angle).

Excluded studies

We excluded nine studies in total. Four randomised trials were identified with AMD endpoints (Arnold 2013; Feher 2005; García Layana 2013; Scorolli 2002), however these were excluded since the supplement used contained additional antioxidants and it was not possible to isolate the effects of the omega 3 LCPUFA. One study (Ziegler 2013) was a commentary. Two further trials (Huang 2008; Johnson 2008) investigated the bioavailability of omega 3 LCPUFA following supplementation with DHA and EPA with or without the xanthophylls lutein and zeaxanthin. Another study (NCT01258335) used multifocal electroretinograms to assess the safety of high‐dose omega 3 fatty acids, but did not report AMD outcomes. Similarly for the OPAL study, which investigated omega 3 LCPUFA supplements for cognitive impairment, eye data were collected in a subset of participants but no AMD outcomes were available.

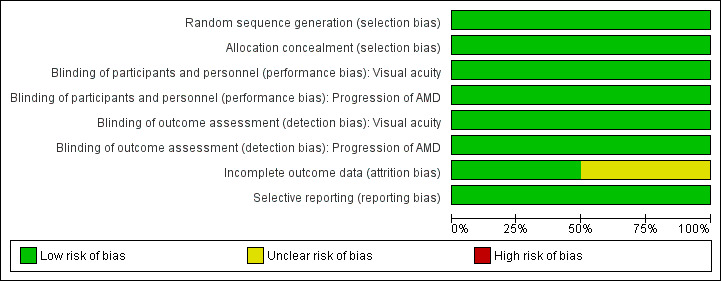

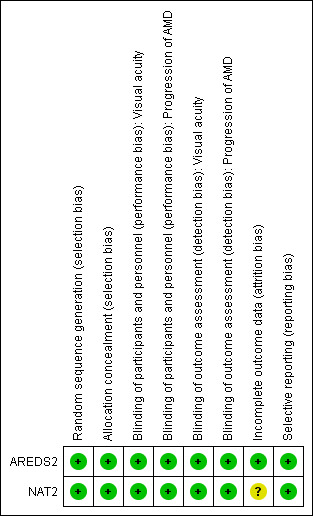

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 and Figure 3 summarise the 'risk of bias' assessment. Overall, we considered the trials to be at low risk of bias for the main types of bias.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

AREDS2 randomised participants using a random block design, which was conducted by the AREDS2 Co‐ordinating Centre. NAT2 used a computer generated random sequence that was carried out by an independent auditor.

Masking

In AREDS2 and NAT2 participants and investigators were masked to the treatment assignment during the study. In AREDS2 the study supplements were identical in appearance, size, smell and taste to their placebo counterparts. In NAT2 the placebo contained olive oil and had the same appearance and weight as the active treatment.

Incomplete outcome data

In AREDS2 missing outcome data were balanced in numbers across the intervention and placebo groups with similar reasons for missing data. NAT2 used a per protocol analysis. The main reason for protocol deviation was premature withdrawal, which occurred at a similar rate in the DHA and placebo groups. Other protocol deviations included ‘non‐compliance with study medication or use of non‐permitted medication’. Two hundred and sixty three of the original 300 participants randomised were included in the analysis.

Selective reporting

For both trials all outcomes that are of interest in this review were reported in the pre‐specified way.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Prevention of AMD

We did not identify any trials of omega 3 fatty acids in people without AMD.

Slowing the progression of AMD

New visual loss attributed to AMD

Visual acuity data was reported by both trials as a dichotomous outcome (loss of 3 or more lines of visual acuity).

NAT2 reported visual acuity outcomes at 12, 24 and 36 months. At each of these time points there was no evidence of a protective effect of omega 3 fatty acids, but the estimates were uncertain with wide confidence intervals (CIs): at 12 months, RR 6.57, 95% CI 0.82 to 52.65, participants = 254; at 24 months, RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.45, participants = 236; and at 36 months, RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.26, participants = 230.

AREDS2 reported visual acuity outcomes at 60 months (adjusted for baseline AMD status) as a hazard ratio (HR). Again there was no little or no evidence of an effect: HR 0.96 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.10, participants = 2080).

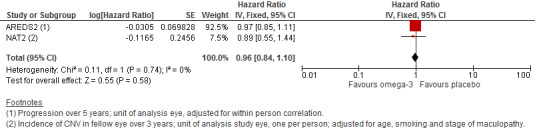

Progression of AMD

Both of the included trials reported data on progression of AMD as time to occurrence of advanced AMD. This was defined as either GA or CNV in either eye in AREDS2 and CNV in the study eye in NAT2. The pooled analysis included 2343 people who experienced 1071 advanced AMD events. The results were reasonably consistent and provided no evidence of any beneficial effect of omega 3 supplementation, pooled HR 0.96 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.10) (Figure 4).

4.

Forest plot of comparison (Analysis 1.1): 1 Omega 3 fatty acids versus control, outcome: 1.10 Progression of AMD.

NAT2 reported the incidence of CNV at 12, 24 and 36 months. At each of these time points there was no evidence of a protective effect of omega 3 fatty acids, but the estimates were uncertain with wide CIs (at 12 months, RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.34, participants = 263; at 24 months, RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.40, participants = 224; and at 36 months, RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.38, participants = 195).

Quality of life

Neither of the trials reported data on quality of life.

Adverse effects

AREDS2 reported 'serious' adverse events only (Table 3). The number of events was similar in the intervention and placebo groups (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.09, participants = 2080). In NAT2, the frequency of adverse events similarly did not differ between the two arms of the study (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.13, participants = 263). Five participants (3.7%) in the omega 3 group and two participants (1.6%) in the placebo group experienced adverse reactions that were considered by the authors to be potentially treatment‐related (including gastrointestinal disorders, allergic dermatitis and breath odour).

1. Adverse effects.

| Adverse effects |

Omega 3 N (%) |

Placebo N (%) |

| AREDS 2 | ||

| Total number of participants | N = 1068 | N = 1012 |

| Participants with ≥ 1 adverse event · Cardiac disorders · Gastrointestinal disorders · Infections · Neoplasms · Nervous system disorders · Respiratory and chest disorders |

505 (47.3) 119 (11.1) 58 (5.4) 103 (9.6) 83 (7.8) 72 (6.7) 37 (3.5) |

479 (47.3) 96 (9.5) 76 (7.5) 90 (8.9) 80 (7.9) 66 (6.5) 44 (4.3) |

| NAT‐2 | ||

| Total number of participants | N = 134 | N = 129 |

| Total adverse events · Treatment emergent adverse events* · Ocular · Serious non‐ocular |

125 (83.3) 5 (4.7) 88 (58.4) 31 (23.1) |

115 (77.7) 2 (1.6) 74 (50.0) 30 (23.6) |

* As defined by the study authors (including gastrointestinal disorders, allergic dermatitis and breath odour)

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review provides evidence that dietary omega 3 LCPUFA supplementation does not slow the progression of AMD or reduce the risk of developing moderate to severe visual loss. The review included data from two RCTs that randomised 2343 individuals with AMD to receive either omega 3 fatty acid supplements or placebo. Duration of supplementation ranged from three to five years. No statistically significant effect on incidence of advanced AMD, progression to advanced AMD or on moderate to severe visual loss were observed. The number of adverse events was similar between the intervention and placebo groups.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The results from both trials were reasonably consistent although the main evidence for a null effect comes from the AREDS2 trial. This was a large well‐conducted randomised study and therefore any potential biases would have been minimised. There are still some unanswered questions, for example we do not know whether the effects of the intervention differ in different populations (for example different ethnicities, nutritional states) or stage of the disease, and whether the composition (EPA:DHA ratio) or source of omega 3 PUFA (oily fish versus fish oil supplements) is important.

We did not identify any trials of supplementation in the general population, that is we do not know whether omega 3 supplementation prevents AMD.

Quality of the evidence

Overall we judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate or high. We downgraded some outcomes for imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

We followed standard procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A systematic review of the effect of dietary omega 3 fatty acids on progression of AMD, including only one RCT and one prospective cohort study, found inconclusive evidence for a beneficial effect (Hodge 2007). Although two systematic reviews (Chong 2009; Hodge 2006) of omega 3 fatty acids for primary prevention of AMD found some evidence based on observational studies that consumption of fish and foods rich in omega 3 LCPUFA was associated with a lower risk of AMD, the authors of both reviews concluded that the lack of evidence from RCTs precluded recommending increasing dietary intake omega 3 fatty acids specifically for AMD prevention.

Omega 3 fatty acids have been extensively studied for their potential health benefits. However, there is continuing controversy regarding their effectiveness. For example, a Cochrane review (Hooper 2004) which included data from 48 RCTs and 41 cohort studies concluded that dietary or supplemental omega 3 fats did not alter total mortality, combined cardiovascular events or cancers in people with, or at high risk of, cardiovascular disease or in the general population. Randomisation to omega 3 fats increased the risk of dropping out due to side effects (RR 1.62, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.40). The most common side effects included a bad or fishy taste or belching (RR 3.63, 95% CI 1.97 to 6.67) and nausea (RR 3.88, 95% CI 1.42 to 10.58).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Although observational studies have shown that the consumption of dietary omega 3 fatty acids or increased fish intake may confer protection against age‐related macular degeneration (AMD) and reduce the risk of progression to advanced AMD, there is no evidence from RCTs to support increasing omega 3 intake for the explicit purpose of preventing or slowing the progression of AMD.

Implications for research.

The lack of an effective treatment for the majority of individuals with AMD represents a major public health problem. Reducing the risk of developing AMD or slowing its progression through dietary modification remains an important area for future research. In nutritional cohort studies, residual confounding from other dietary or lifestyle variables is always a problem. Such confounding can be avoided in RCTs. The trials reported in this review failed to demonstrate any protective effects of omega 3 supplementation in people with AMD who were at high risk of progressing to advanced disease. However, there are still some unanswered questions in terms of target population and the composition and timing of the intervention. RCTs are expensive to conduct and a more cost‐effective approach would be to include AMD outcomes in large trials of other morbidities for example cancer or cardiovascular disease. One such trial, VITAL‐AMD, is ongoing.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 April 2015 | Amended | Table 3 reformatted |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 8, 2012 Review first published: Issue 11, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 April 2015 | Amended | Amended confidence interval in abstract |

| 11 March 2015 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Issue 4, 2015: Two trials were identified that met the inclusion criteria (AREDS2; NAT2) |

| 11 March 2015 | New search has been performed | Issue 4, 2015: Electronic searches updated |

Notes

None

Acknowledgements

We thank Catey Bunce, Andrew Law and William G Christen for their comments on this review. We are grateful to Iris Gordon from the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (CEVG) for preparing the electronic searches for this review and to Anupa Shah, Managing Editor for CEVG for her assistance throughout the review process.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Macular Degeneration #2 MeSH descriptor Retinal Degeneration #3 MeSH descriptor Retinal Neovascularization #4 MeSH descriptor Choroidal Neovascularization #5 MeSH descriptor Macula Lutea #6 macula* near lutea* #7 (macula* or retina* or choroid*) near/4 degenerat* #8 (macula* or retina* or choroid*) near/4 neovascul* #9 maculopath* #10 AMD or ARMD or CNV #11 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10) #12 MeSH descriptor Fatty Acids, Omega‐3 #13 fatty near/2 acid* #14 omega 3 #15 polyunsaturated #16 LCPUFA* or PUFA* #17 docosahexaenoic or DHA* #18 eicosapentaenoic or EPA* #19 (#12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18) #20 (#11 AND #19)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (OvidSP) search strategy

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. (randomized or randomised).ab,ti. 3. placebo.ab,ti. 4. dt.fs. 5. randomly.ab,ti. 6. trial.ab,ti. 7. groups.ab,ti. 8. or/1‐7 9. exp animals/ 10. exp humans/ 11. 9 not (9 and 10) 12. 8 not 11 13. exp retinal degeneration/ 14. retinal neovascularization/ 15. choroidal neovascularization/ 16. exp macula lutea/ 17. maculopath$.tw. 18. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 degener$).tw. 19. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 neovasc$).tw. 20. (AMD or ARMD or CNV).tw. 21. or/13‐20 22. Fatty Acids, Omega‐3/ 23. (fatty adj2 acid$).tw. 24. omega 3.tw. 25. polyunsaturated.tw. 26. (LCPUFA$ or PUFA$).tw. 27. (docosahexaenoic or DHA$).tw. 28. (eicosapentaenoic or EPA$).tw. 29. or/22‐28 30. 21 and 29 31. 12 and 30

The search filter for trials at the beginning of the MEDLINE strategy is from the published paper by Glanville et al (Glanville 2006).

Appendix 3. EMBASE (OvidSP) search strategy

1. exp randomized controlled trial/ 2. exp randomization/ 3. exp double blind procedure/ 4. exp single blind procedure/ 5. random$.tw. 6. or/1‐5 7. (animal or animal experiment).sh. 8. human.sh. 9. 7 and 8 10. 7 not 9 11. 6 not 10 12. exp clinical trial/ 13. (clin$ adj3 trial$).tw. 14. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj3 (blind$ or mask$)).tw. 15. exp placebo/ 16. placebo$.tw. 17. random$.tw. 18. exp experimental design/ 19. exp crossover procedure/ 20. exp control group/ 21. exp latin square design/ 22. or/12‐21 23. 22 not 10 24. 23 not 11 25. exp comparative study/ 26. exp evaluation/ 27. exp prospective study/ 28. (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).tw. 29. or/25‐28 30. 29 not 10 31. 30 not (11 or 23) 32. 11 or 24 or 31 33. exp retina degeneration/ 34. retina neovascularization/ 35. subretinal neovascularization/ 36. exp retina macula lutea/ 37. maculopath$.tw. 38. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 degener$).tw. 39. ((macul$ or retina$ or choroid$) adj3 neovasc$).tw. 40. (AMD or ARMD or CNV).tw. 41. or/33‐40 42. omega 3 fatty acid/ 43. (fatty adj2 acid$).tw. 44. omega 3.tw. 45. polyunsaturated.tw. 46. (LCPUFA$ or PUFA$).tw. 47. docosahexaenoic acid/ 48. (docosahexaenoic or DHA$).tw. 49. icosapentaenoic acid/ 50. (eicosapentaenoic or EPA$).tw. 51. or/42‐50 52. 41 and 51 53. 32 and 52

Appendix 4. LILACS search strategy

macular degenerat$ or AMD or AMRD or CNV and omega or fatty acid or polyunsaturated or docosahexaenoic or eicosapentaenoic

Appendix 5. metaRegister of Controlled Trials search strategy

(macular degeneration) AND omega

Appendix 6. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

(Macular Degeneration) AND Omega 3

Appendix 7. ICTRP search strategy

(Macular Degeneration) AND Omega 3

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Omega 3 fatty acids versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Progression of AMD | 2 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.84, 1.10] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega 3 fatty acids versus control, Outcome 1 Progression of AMD.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

AREDS2.

| Methods | Parallel group RCT, 2 x 2 factorial design Both eyes included in the trial, both eyes received same treatment, adjustment made for within person correlation |

|

| Participants | Country: USA Setting: community Number of participants: 2080, 55% women Average age: 74 years Age range: 50 to 85 years Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

Approximately 90% of participants were taking an additional multivitamin supplement |

|

| Interventions |

Omega 3 fatty acids were DHA (350 mg per day) and EPA (650 mg per day). Composition of placebo not specified All participants were asked to take the original AREDS formulation (vitamin C 500 mg, vitamin E 400 IU, beta‐carotene 15 mg, zinc oxide 80 mg, cupric oxide 2 mg). Those who agreed to take AREDS and consented to a second randomisation were assigned as follows

The participants who did not agree to a secondary randomisation largely took the AREDS formula: omega 3 fatty acids group n = 305 (28.6%); placebo group n = 265 (26.2%) Participants who were current smokers or former smokers who had stopped smoking within the year before enrolment were randomly assigned to 1 of the 2 arms without beta‐carotene Duration: 5 years |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome:

Secondary outcomes:

Follow‐up: annually |

|

| Dates participants recruited | 10/2006 to 09/2008 | |

| Declaration of interest | Yes ‐ reported in paper. Including patent for AREDS formula | |

| Sources of funding | This study was supported by the intramural program funds and contracts from the National Eye Institute (NEI), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, Maryland (contract HHS‐N‐260‐2005‐00007‐C; ADB contract N01‐EY‐5‐0007). Funds were contributed by the following NIH institutes: Office of Dietary Supplements; National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine; National Institute on Aging; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The study medications and raw materials were provided by Alcon, Bausch & Lomb, DSM, and Pfizer | |

| Notes | In the primary randomisation 84% of participants took 75% of the study medications http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00345176 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “A random block design was implemented using the AREDS2 Advantage Electronic Data Capture system by the AREDS2 Coordinating Center (The EMMES Corporation, Rockville, MD) and stratified by clinical center and AMD status (large drusen both eyes or large drusen in 1 eye and advanced AMD in the fellow eye) to ensure approximate balance across centers over time.” Page 2285 of protocol paper |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Placebo‐controlled study “Participants and study personnel were masked to treatment assignment in both randomizations.” Page E2 of main study report |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Visual acuity | Low risk | “Participants and study personnel were masked to treatment assignment in both randomizations.” Page E2 of main study report |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Progression of AMD | Low risk | “Participants and study personnel were masked to treatment assignment in both randomizations.” Page E2 of main study report |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Visual acuity | Low risk |

“Participants and study personnel were masked to treatment assignment in both randomizations.” Page E2 of main study report |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Progression of AMD | Low risk |

“Participants and study personnel were masked to treatment assignment in both randomizations.” Page E2 of main study report CNV was determined by masked readers from stereoscopic fundus photographs |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Follow‐up was high and balanced across groups

|

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Not detected |

NAT2.

| Methods | Parallel‐group RCT One eye only included, study eye was selected on the basis of early AMD with neovascular AMD (CNV) in the fellow eye |

|

| Participants | Country: France Setting: community Number of participants: 300, 65% women Average age: 74 years Age range: 55 to 85 years Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions |

Omega 3 fatty acids were 3 fish oil capsules, each capsule contained: DHA (280 mg), EPA (90 mg) and vitamin E (2 mg) (Reti‐Nat, provided by Bausch & Lomb, Montpellier, France) Placebo contained 602 mg of olive oil Duration: 3 years |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome:

Secondary outcome:

Follow‐up: annually |

|

| Dates participants recruited | 12/2003 to 10/2005 | |

| Declaration of interest | Eric H Souied: Consultant and lecturer—Laboratoire Bausch & Lomb Chauvin

Pascale Benlian: Financial support and lecturer—Laboratoire Bausch & Lomb Chauvin Cécile Delcourt: Consultant and financial support—Laboratoire Bausch & Lomb Chauvin; Consultant and financial support—Laboratoires Théa; Consultant—Novartis |

|

| Sources of funding | Sponsored by Laboratoire Bausch & Lomb Chauvin, Montpellier | |

| Notes | http://www.controlled‐trials.com/ISRCTN98246501 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk |

"QL‐Ranclin software (Qualilab, Olivet, France) was used to generate the randomization list before enrolment." Souied et al 2013 p3 |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk |

"The patients and the study personnel both were blinded to the treatment assignment." Souied et al 2013 p3 |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Visual acuity | Low risk | Not well reported. However, Qualilab provides an independent trial auditing service (not clear if this was the case here). No information provided regarding the outcome assessors (?study personnel), however it is likely that they remained masked as to the allocation |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) Progression of AMD | Low risk | Not well reported. However, Qualilab provides an independent trial auditing service (not clear if this was the case here). No information provided regarding the outcome assessors (?study personal), however it is likely that they remained masked as to the allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Visual acuity | Low risk | Not well reported. However, Qualilab provides an independent trial auditing service (not clear if this was the case here). No information provided regarding the outcome assessors (?study personal), however it is likely that they remained masked as to the allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) Progression of AMD | Low risk | Not well reported. However, Qualilab provides an independent trial auditing service (not clear if this was the case here). No information provided regarding the outcome assessors (?study personal), however it is likely that they remained masked as to the allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Used a per protocol analysis. Main reason for protocol deviation was premature withdrawal which occurred at a similar rate in DHA and placebo groups. Other protocol deviations included ‘non‐compliance with study medication or use of non‐permitted medication’; 263 of the original 300 patients randomised were included in the analysis |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All pre‐specified primary outcomes reported. All secondary outcomes (with the exception of mERG listed in trial protocol) were reported |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Arnold 2013 | Omega 3 fatty acids combined with carotenoids. Not able to isolate the effect of omega 3 treatment |

| Feher 2005 | A total of 106 participants with early AMD were randomised to receive a supplement containing acetyl‐L‐carnitine, co‐enzyme Q10 and omega 3 fatty acids or placebo for 12 months. The outcomes measured were change in visual field defect, visual acuity and AMD grading from baseline. This study was excluded since it was not possible to isolate the specific effects of the omega 3 treatment |

| García Layana 2013 | Omega 3 fatty acids combined with carotenoids. Not able to isolate the effect of omega 3 treatment |

| Huang 2008 | This was a bioavailability study for the AREDS2 trial; 40 participants with AMD were randomly assigned to receive lutein and zeaxanthin, DHA/EPA or placebo for 6 months. Serum levels of lutein, zeaxanthin, DHA and EPA were measured in addition to macular pigment optical density. This study was excluded since no data on AMD outcomes were reported |

| Johnson 2008 | A total of 49 participants recruited from the general population were randomly assigned to placebo, lutein or lutein plus DHA. Supplements were taken for 4 months. The outcomes were serum levels of lutein and DHA and macular pigment optical density. This study was excluded since no data on AMD outcomes were reported |

| NCT01258335 | The ‘Short Term Ocular Safety Assessment of High Dose Omega 3 Supplementation for Age‐Related Macular Degeneration’ study was a RCT that used multifocal ERGs to establish the safety of omega LCPUFA supplements. The trialists confirmed that no AMD outcomes were collected and safety data or quality of life data were not available |

| OPAL | The ‘Older People And n‐3 Long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids’ study was a randomised trial to assess the effects of oral supplementation with omega 3 LCPUFAs on cognitive decline. The effect of the supplement on visual function was also investigated in a sub‐set of participants by assessing rod photoreceptor response to light and visual‐cortical integration. Trialists confirmed that no AMD outcomes were collected and the study was therefore excluded. Reporting of minor adverse events was similar between trial arms |

| Scorolli 2002 | A total of 35 participants with bilateral late AMD were randomly assigned to either receive (20 patients) or not receive (15 patients) a supplement containing vitamin E and polyunsaturated fatty acid for 60 days after photodynamic therapy. The outcomes measured were visual acuity (logMAR) and retinal metabolic function. This study was excluded since it was not possible to isolate the specific effects of the omega 3 treatment |

| Ziegler 2013 | Commentary |

AMD: age‐related macular degeneration DHA: docosahexaenoic acid EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid ERG: electroretinogram LCPUFA: long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids logMAR: logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution RCT: randomised controlled trial

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

NCT02264938.

| Trial name or title | Drusen morphology changes in non‐exudative age‐related degeneration after oral antioxidants supplementation |

| Methods | Randomised unmasked controlled trial of oral supplementation with a preparation containing antioxidants and omega 3 fatty acids for one year compared to no supplement (observation) |

| Participants | People with AREDS category 2 and 3 AMD |

| Interventions | Daily dose of a AREDS‐like supplement containing lutein (12 mg), zeaxanthin (2 mg), astaxanthin (8 mg), omega 3 fatty acids (DHA 540 mg and EPA 360 mg), vitamin C (40 mg), vitamin E (20 mg), zinc (16 mg) and copper (2 mg) |

| Outcomes | Changes in drusen morphology (volume and area) measured automatically with Topcon 3D OCT‐2000 at baseline and 12 months |

| Starting date | January 2013. Final data collection date for primary outcome measure July 2014 |

| Contact information | See ClinicalTrials.gov website for details |

| Notes | http://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02264938 |

VITAL‐AMD.

| Trial name or title | Ancillary AMD study to the vitamin D and omega 3 trial (VITAL) |

| Methods | VITAL is a randomised, double‐masked, placebo‐controlled, 2 x 2 factorial trial of vitamin D and marine omega 3 fatty acid (eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)) supplements in the primary prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease |

| Participants | The study planned to enrol 20,000 male or female participants aged 50 years without cancer or cardiovascular disease at baseline |

| Interventions | The intervention groups received oral supplementation with vitamin D (cholecalciferol; 2000 IU) or marine omega 3 fatty acid (EPA + DHA, 1 g/d) supplements. Control groups received an inactive placebo |

| Outcomes | The AMD endpoint will be based on medical record‐confirmed self reports and retinal photographs |

| Starting date | July 2010 End date: June 2016 |

| Contact information | See ClinicalTrials.gov website for details |

| Notes | http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01169259 |

AMD: age‐related macular degeneration LCPUFA: long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids

Differences between protocol and review

None

Contributions of authors

JL assessed studies for inclusion and exclusion, assessed risk of bias, extracted data, entered data and authored the first draft of the review JE assessed studies for inclusion and exclusion, assessed risk of bias, extracted data, entered data reviewed and commented on the text of the review

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

National Institute for Health Research, UK.

- Richard Wormald, Co‐ordinating Editor for the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (CEVG) acknowledges financial support for his CEVG research sessions from the Department of Health through the award made by the National Institute for Health Research to Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology for a Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology.

- The NIHR also funds the CEVG Editorial Base in London.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health.

Declarations of interest

JL: none known JE: none known

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

AREDS2 {published and unpublished data}

- Age‐Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. Lutein + zeaxanthin and omega‐3 fatty acids for age‐related macular degeneration: the Age‐Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;309(19):2005‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew EY, Clemons T, SanGiovanni JP, Danis R, Domalpally A, McBee W, et al. The Age‐Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2): study design and baseline characteristics (AREDS2 report number 1). Ophthalmology 2012;119(11):2282‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NAT2 {published data only}

- Souied EH, Delcourt C, Querques G, Bassols A, Merle B, Zourdani A, et al. Oral docosahexaenoic acid in the prevention of exudative age‐related macular degeneration: the Nutritional AMD Treatment 2 study. Ophthalmology 2013;120(8):1619‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Arnold 2013 {published data only}

- Arnold C, Winter L, Fröhlich K, Jentsch S, Dawczynski J, Jahreis G, et al. Macular xanthophylls and ω‐3 long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in age‐related macular degeneration: a randomized trial. JAMA Ophthalmology 2013;131(5):564‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Feher 2005 {published data only}

- Feher J, Kovacs B, Kovacs I, Schveoller M, Papale A, Balacco Gabrieli C. Improvement of visual functions and fundus alterations in early age‐related macular degeneration treated with a combination of acetyl‐L‐carnitine, n‐3 fatty acids, and coenzyme Q10. Ophthalmologica 2005;219(3):154‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

García Layana 2013 {published data only}

- García‐Layana, A, Recalde S, Alamán AS, Robredo PF. Effects of lutein and docosahexaenoic acid supplementation on macular pigment optical density in a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2013;5(2):543‐51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Huang 2008 {published data only}

- Huang LL, Coleman HR, Kim J, Monasterio F, Wong WT, Schleicher RL, et al. Oral supplementation of lutein/zeaxanthin and omega‐3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in persons aged 60 years or older, with or without AMD. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 2008;49(9):3864‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Johnson 2008 {published data only}

- Johnson EJ, Chung HY, Caldarella SM, Snodderly DM. The influence of supplemental lutein and docosahexaenoic acid on serum, lipoproteins, and macular pigmentation. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008;87(5):1521‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NCT01258335 {published and unpublished data}

- NCT01258335. Short term ocular safety assessment of high dose omega‐3 supplementation for age‐related macular degeneration. clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01258335 (accessed 8 June 2012).

OPAL {published and unpublished data}

- ISRCTN72331636. The OPAL study: older people and n‐3 long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. controlled‐trials.com/ISRCTN72331636 (accessed 11 June 2012).

Scorolli 2002 {published data only}

- Scorolli L, Scalinci SZ, Limoli PG, Morara M, Vismara S, Scorolli L, et al. Photodynamic therapy for age related macular degeneration with and without antioxidants [La phototherapie dynamique de la degenerescence maculaire liee a l'age avec ou sans therapie aux antioxydants]. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology 2002;37(7):399‐404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ziegler 2013 {published data only}

- Ziegler R. Supplementary carotinoids and omega‐3‐fatty acids are ineffective [Zusatzliche carotinoide und omega‐3‐fettsauren wirkungslos]. Medizinische Monatsschrift fur Pharmazeuten 2013;36(9):348‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

NCT02264938 {published and unpublished data}

- NCT02264938. Drusen morphology changes in nonexudative age‐related degeneration using spectral domain optical coherence tomography after oral antioxidants supplementation: one‐year results. ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02264938 (accessed 9 February 2015).

VITAL‐AMD {published and unpublished data}

- NCT01169259. Vitamin D and Omega‐3 Trial (VITAL). clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01169259 (accessed 9th February 2015).

Additional references

AREDS 1999

- Anonymous. The Age‐Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS): design implications. AREDS report no. 1. Controlled Clinical Trials 1999;20(6):573‐600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bunce 2010

- Bunce C, Xing W, Wormald R. Causes of blind and partial sight certifications in England and Wales: April 2007‐March 2008. Eye 2010;24(11):1692‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burdge 2002

- Burdge GC, Jones AE, Wootton SA. Eicosapentaenoic and docosapentaenoic acids are the principal products of alpha‐linolenic acid metabolism in young men. British Journal of Nutrition 2002;88(4):355‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chong 2009

- Chong EW, Robman LD, Simpson JA, Hodge AM, Aung KZ, Dolphin TK, et al. Fat consumption and its association with age‐related macular degeneration. Archives of Ophthalmology 2009;127(5):674‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Christen 2011

- Christen WG, Schaumberg DA, Glynn RJ, Buring JE. Dietary omega‐3 fatty acid and fish intake and incident age‐related macular degeneration in women. Archives of Ophthalmology 2011;129(7):921‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Evans 2012a

- Evans JR, Lawrenson JG. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for preventing age‐related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000253.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Evans 2012b

- Evans JR, Lawrenson JG. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplements for slowing the progression of age‐related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000254.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Glanville 2006

- Glanville JM, Lefebvre C, Miles JN, Camosso‐Stefinovic J. How to identify randomized controlled trials in MEDLINE: ten years on. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2006;94(2):130‐6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hodge 2006

- Hodge WG, Schachter HM, Barnes D, Pan Y, Lowcock EC, Zhang L, et al. Efficacy of omega‐3 fatty acids in preventing age‐related macular degeneration: a systematic review. Ophthalmology 2006;113(7):1165‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hodge 2007

- Hodge WG, Barnes D, Schachter HM, Pan YI, Lowcock EC, Zhang L, et al. Evidence for the effect of omega‐3 fatty acids on progression of age‐related macular degeneration: a systematic review. Retina 2007;27(2):216‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hooper 2004

- Hooper L, Thompson RL, Harrison RA, Summerbell CD, Moore H, Worthington HV, et al. Omega 3 fatty acids for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003177.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kishan 2011

- Kishan AU, Modjtahedi BS, Martins EN, Modjtahedi SP, Morse LS. Lipids and age‐related macular degeneration. Survey of Ophthalmology 2011;56(3):195‐213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klein 1991

- Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, Segal P, Klein BE, Hubbard L. The Wisconsin age‐related maculopathy grading system. Ophthalmology 1991;98(7):1128‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koto 2007

- Koto T, Nagai N, Mochimaru H, Kurihara T, Izumi‐Nagai K, Satofuka S, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid is anti‐inflammatory in preventing choroidal neovascularization in mice. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 2007;48(9):4328‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lim 2012

- Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, Holz FG, Wong TY. Age‐related macular degeneration. Lancet 2012;379(9827):1728‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Owen 2012

- Owen CG, Jarrar Z, Wormald R, Cook DG, Fletcher AE, Rudnicka AR. The estimated prevalence and incidence of late stage age related macular degeneration in the UK. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2012;96(5):752‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Rudnicka 2012

- Rudnicka AR, Jarrar Z, Wormald R, Cook DG, Fletcher A, Owen CG. Age and gender variations in age‐related macular degeneration prevalence in populations of European ancestry: a meta‐analysis. Ophthalmology 2012;119(3):571‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SanGiovanni 2005

- SanGiovanni JP, Chew EY. The role of omega‐3 long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in health and disease of the retina. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2005;24(1):87‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

SanGiovanni 2009

- SanGiovanni JP, Agron E, Clemons TE, Chew EY. Omega‐3 long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acid intake inversely associated with 12‐year progression to advanced age‐related macular degeneration. Archives of Ophthalmology 2009; Vol. 127, issue 1:110‐2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Tan 2009

- Tan JS, Wang JJ, Flood V, Mitchell P. Dietary fatty acids and the 10‐year incidence of age‐related macular degeneration: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Archives of Ophthalmology 2009;127(5):656‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tuo 2009

- Tuo J, Ross RJ, Herzlich AA, Shen D, Ding X, Zhou M, et al. A high omega‐3 fatty acid diet reduces retinal lesions in a murine model of macular degeneration. American Journal of Pathology 2009;175(2):799‐807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Lawrenson 2012a

- Lawrenson JG, Evans JR. Omega 3 fatty acid supplementation for preventing and slowing the progression of age‐related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010015] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lawrenson 2012b

- Lawrenson JG, Evans JR. Omega 3 fatty acids for preventing or slowing the progression of age‐related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010015.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]