Introduction

The hype about the swine-flu pandemic is over. Should we, therefore, forget about this episode? We feel that there is a need to evaluate on a national as well as international level the events which have occurred and the mistakes which have been made.

The announcement of the swine-flu pandemic on June 11, 2009 by the World Health Organization (WHO) was a real precedent. In May 2009 WHO eliminated the severity of disease from the definition of stage six of a pandemic and demanded as sole criterion the swift and worldwide spread of a new virus against which the population has no immunity.

For the first time expensive measures against a pandemic such as the production of vaccines and mass vaccination were initiated worldwide. The pandemic stage six has been kept until August 2010, although there was neither any indication for serious health threats from A/H1N1 influenza, nor was the virus “new”.

A historical perspective

Neither WHO nor national pandemic expert committees nor governments have informed the public that the A/H1N1 virus has been known for decades. In the 1970ies soldiers coming from Vietnam brought the virus as the so called Asian swine flu to the US. In 1976 a vaccination campaign was started and about 40 million US-citizens were vaccinated, because the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) feared, that the A/H1N1 virus might be similar to the virus of the Spanish influenza in 1918–1920 with 25–40 million deaths [1]. The A/H1N1 vaccination campaign was stopped abruptly when it was realized that the virus produced only a mild disease, while the vaccine produced a number of severe neurological side effects, namely Guillain-Barre-Syndrome [2].

In their report “The epidemic that never was” Neustadt and Fineberg [3, 4] concluded that

“ overconfidence by specialists in theories extrapolated from meagre evidence

conviction fuelled by a conjunction of some pre-existing personal agendas

premature commitment to deciding more than had to be decided

failure to address uncertainties in such a way as to prepare for reconsideration

insufficient questioning of scientific logic and of implementation prospects”

were all points that were detrimental in the decision making process in 1976. Obviously, these lessons were not learned.

The 2009/2010 A/H1N1 pandemic

A similarly benign evolvement of the 2009/2010 A/H1N1 pandemic has been observed around the world. In Germany about 260 000 people were supposed to be infected and only a very small number of deaths could be attributed to the A/H1N1 pandemic, namely 258 [5] which corresponds to a case fatality of 0.1% (see Table 1). Hardly any infection with A/H1N1 has been found among people aged 60 and over, a clear indication that older people had already been in contact with the A/H1N1 virus and/or with vaccines containing A/H1N1 virus antigen [6].

Table 1.

Case fatality of known influenza viruses

| Influenza type | Case fatality (%) |

|---|---|

| Spanish flu | 3.0 |

| A/H5N1 (avian flu) | 68.0 |

| SARS (corona) | 9.6 |

| Seasonal influenza | 0.4 |

| A/H1N1 (swine flu) | 0.1 |

In spite of unconvincing data from Mexico, WHO followed the advice of its emergency committee and declared the A/H1N1 pandemic on June 11, 2009, thus triggering a cascade of national actions that had been prepared after the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and avian flu pandemic fears.

In Germany 50 million doses of vaccine were ordered by the government costing more than 500 million Euro. Finally, less than 7 million doses were used for vaccination. Interestingly, the contracts with the vaccine manufacturer for Germany, “GlaxoSmithKline”, were signed already in 2007 after a new pandemic mock-up vaccine (Pandemrix), based on the avian flu A/H5N1 viral antigen, had been licensed. There were no changes made to the contract for the swine flu pandemic in 2009.

WHO based its evaluations merely on the re-assortment theory promoted by molecular virologists, specifically that two different viruses infecting a host at the same time may merge (=re-assort) into a new highly pathogenic killer virus. These killer virus scenarios, first propagated by government agencies and vaccine producers for SARS, avian flu, and swine-flu, and predicting millions of deaths, call on deeply rooted fears in humans with respect to plagues, such as the Spanish Influenza (1918–1920). They never became true and not a single death from SARS or avian flu occurred in Germany, and the swine flu pandemic (258 deaths) did by far not reach the usual death toll of the seasonal flu epidemics.

A decade of angst campaigns

In recent years we have been witnessing angst campaigns with regard to SARS in 2002/2003, with regard to avian flu in 2005/2006 and now we have experienced the so called swine flu pandemic. The probable worldwide toll for SARS amounts to 8,098 cases of which 774 died (case fatality 9.6%) [7]. Avian flu so far has affected some 496 individuals, killing 293 of them [8]. (see Table 1) It is important to know that avian flu is only contracted by close contact between birds and humans and therefore remains a regional zoonosis. Nevertheless, avian flu became the model for pandemic flu scenarios.

What have we learned from the swine-flu-affair?

What needs to be done?

Firstly The current concept of pandemics has to be reconsidered and it should be accepted that the spread and severity of infectious diseases is generally more dependent on social conditions of populations than on the properties of the infectious agent [9].

Most people including scientists and politicians are hardly aware of the fact, that the A/H1N1 virus of the Spanish Influenza has hit populations stricken by war and hunger: Poor, frail and undernourished people paid the highest death toll. According to Murray, Lopez et al [10] mortality figures from the Spanish flu showed a 31-fold variability according to the nutritional- and social status of the respective populations; in a hypothetical re-occurrence of the Spanish Influenza pandemic, 96% of all deaths would occur in the developing countries and only 4% in the developed world [10]. Therefore, the swine-flu vaccination campaigns in Europe and North America were especially inappropriate.

Obviously, the most effective way to prevent any infectious disease pandemic is to invest in the improvement of social conditions [9, 11]. Tuberculosis is an excellent example. This major scourge was very prevalent and produced a high death toll at the time, when the mycobacterium tuberculosis was detected by Robert Koch [12]. Although there was no effective treatment, the disease declined dramatically with the improvement of social conditions. When streptomycin appeared on the scene (1952) the epidemic in Europe had nearly disappeared.

Secondly Sound infectious disease epidemiology must be applied to the surveillance of influenza epidemics, e.g. define the target population, draw appropriate random samples from the respective population to obtain unbiased estimates of the incidence of flu like symptoms and of the viral status of the sample. Such methodology allows for proper inference of the spread and the virulence of the respective infectious agent. Data currently provided by the Global Influenza Surveillance Network are insufficient; they are not population based and therefore do not provide reliable data on disease severity, nor on case fatality. The data on the seasonal influenza show similar weaknesses and the estimates of disease frequency, mortality, and case fatality are similarly vague [13]. Consequently, the effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination campaigns and of anti-viral medication is more than questionable [13].

Thirdly Conflicts of interest of scientific advisors to WHO or to other international and national public health institutions regarding connections with the respective pharmaceutical industry must be disclosed and acted upon in a similar fashion as is the case for employees of and advisors to WHO regarding the tobacco industry [14].

Fourthly To blame the media alone for the horror scenarios pertaining to the swine-flu pandemic is too simple. The media most often conveyed messages they received from scientists (with hidden links to vaccine producers), representatives of government agencies close to those experts, and WHO. However, contrary to WHO and its experts there were a number of critical journalists questioning the pandemic scenarios. Also not all countries in Europe were following WHO’s advice: The minister of health of Poland decided not to buy any swine-flu vaccine. Consequently, there was no vaccination campaign against A/H1N1 in Poland; however, the course of the disease there was similarly mild as in the other European countries.

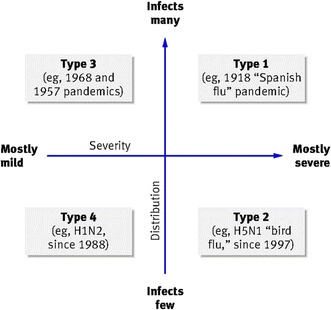

Fifthly WHO failed to give appropriate guidance in the swine flu pandemic. To prevent this from recurring, new strategies for the evaluation of the impact of new infectious diseases are needed. According to the figure by Doshi [15] (see Fig. 1) four scenarios are conceivable: a severe disease infecting many (Type 1), a severe disease infecting few (Type 2), a mild disease infecting many (Type 3) and a mild disease infecting few (Type 4). So far WHO has misclassified SARS, avian flu and swine flu as Type 1 diseases, which produced a hat trick of false alarms within less than a decade [16]. Future WHO emergency committees must comprise scientists from a wide range of disciplines thus diminishing the chance of misclassification of future infectious disease epidemics. Advice from disease experts, e.g. molecular virologists, is important, but final policy recommendations must come from scientists trained in evaluation, priority setting, and public health and being fully independent [17].

Fig. 1.

Proposed classification of impact of new infectious diseases [15]

Resume

In light of the fact, that life expectancy in the western world has been increasing by 2–2.5 years per decade for the last halve century, the angst campaigns concerning influenza pandemics triggered by virologists are out of range and irresponsible. It is ironic, that during the decade of continuous alarms for pandemics, with millions of deaths predicted from SARS, avian flu and swine-flu, life expectancy e.g. in Germany increased by nearly 3 years for both men and women, reaching more than 77 and 82 years for men and women, respectively [18].

Public health perspective

It is now time to re-evaluate public health strategies and to ask the question what really helps to reduce the burden of morbidity and mortality in Europe and worldwide? Fortunately, we know the great killers, namely cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancers and chronic respiratory diseases [19] (plus malaria, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis in a number of developing countries). And we also know that 90% of diabetes mellitus type II, 85% of lung cancer, 80% of coronary heart disease, 70% of stroke and 70% of colon cancer are preventable by life style modification and public health measures [20] such as improved social conditions, healthy nutrition, increased physical activity and a strict ban on smoking [19].

However, governments and public health services are often paying only lip service to the prevention of these great killers and are instead wasting money on pandemic scenarios whose evidence base is weak. According to the pharmaceutical industry, their worldwide earnings from selling vaccines against the swine flu pandemic amounted to 18 billion Euro. [21].

References

- 1.Retrospective: what happened with swine flu in 1976? http://blogs.sciencemag.org/scienceinsider/2009/04/retrospective-w.htlm. Accessed 27 April 2009.

- 2.Kindy K. Officials are urged to heed lessons of 1976 flu outbreak.www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/05/08/.

- 3.Neustadt RE, Fineberg HV. The epidemic that never was. Policy making and the swine flu scare. New York: Vintage Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fineberg HV. Swine flu of 1976: lessons from the past. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:414–415. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.040609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arbeitsgemeinschaft Influenza:http://influenza.rki.de/saisonberichte_aspx. Accessed 23 Jan 2010.

- 6.NN: Im Blickpunkt Schweinegrippe: alles im griff? arznei-telegramm 2009; 40:93–5.

- 7.World Health Organization. WHO SARS assessment and preparedness framework. WHO, Geneva, 2004.

- 8.www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/cases_table_2009_12_30/en/.

- 9.Ackerknecht EH. Rudolf Virchow. In: Epidemiology and public health. New York: Arno Press; 1981. p. 123–137.

- 10.Murray CJL, Lopez AD, Chin B, Feehan D, Hill KH. Estimation of potential global pandemic influenza mortality on the basis of vital registry data from the 1918–20 pandemic: a quantitative analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:2211–2218. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Commission on social determinants of health final report. Closing the Gap in a Generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Koch R. Die Aetiologie der Tuberculose. Berliner Klin Wschr. 1882;19:221–30.

- 13.Jefferson T. Influenza vaccination: policy versus evidence. BMJ. 2006;333:912–915. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38995.531701.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: WHO; 2003.

- 15.Doshi P. How should we plan for pandemics? BMJ. 2009;339:603–605. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkes N. Why we went over the top in the swine flu battle. BMJ. 2010;340:c789. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonneux L, Van Damme W. Preventing pandemics of panic in a NICE way. BMJ. 2010;340:1308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistisches Bundesamt. Todesursachenstatistik. www.gbe-bund.de Accessed 1 Nov 2010.

- 19.World Health Organization. 2008–2013 Action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

- 20.Willet WC. Balancing life-style and genomics research for disease prevention. Science. 2002;296:695–698. doi: 10.1126/science.1071055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassel L. European Vaccine Manufacturers. Hearing on “The handling of the H1N1 pandemic:more transparency needed?” Council of Europe, Strasbourg, January 26, 2010, http://www.coe.int/t/dc/files/events/2010_H1N1/default_en.asp.