Abstract

Several pathways increase the concentrations of cellular free zinc(II) ions. Such fluctuations suggest that zinc(II) ions are signalling ions used for the regulation of proteins. One function is the inhibition of enzymes. It is quite common that enzymes bind zinc(II) ions with micro- or nanomolar affinities in their active sites that contain catalytic dyads or triads with a combination of glutamate (aspartate), histidine and cysteine residues, which are all typical zinc-binding ligands. However, for such binding to be physiologically significant, the binding constants must be compatible with the cellular availability of zinc(II) ions. The affinity of inhibitory zinc(II) ions for receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase β is particularly high (K i = 21 pM, pH 7.4), indicating that some enzymes bind zinc almost as strongly as zinc metalloenzymes. The competitive pattern of zinc inhibition for this phosphatase implicates its active site cysteine and nearby residues in the coordination of zinc. Quantitative biophysical data on both affinities of proteins for zinc and cellular zinc(II) ion concentrations provide the basis for examining the physiological significance of inhibitory zinc-binding sites in proteins and the role of zinc(II) ions in cellular signalling. Regulatory functions of zinc(II) ions add a significant level of complexity to biological control of metabolism and signal transduction and embody a new paradigm for the role of transition metal ions in cell biology.

Keywords: Zinc, Enzyme inhibition, Enzyme active sites

Introduction

The functions of zinc in proteins are generally referred to as catalytic, structural, and regulatory. The coordination environments of catalytic and structural sites are rather well defined (Auld 2001). However, a consensus is lacking on what defines regulatory zinc sites structurally. Binding of zinc to such sites has to occur in a range of physiological zinc(II) ion concentrations. Only now are concepts emerging to indicate how cellular zinc is buffered and what the physiologically relevant concentrations of zinc(II) ions are. With this knowledge, one can begin to discuss the significance of what are presumed to be regulatory zinc sites in proteins.

In the cell, each metal ion is maintained in a certain range of concentrations in order not to interfere with the functions of other metal ions (Maret 2010). Once metal ions exceed their normal physiological concentrations, they bind at sites where they normally do not bind. The ranges of physiological free metal ion concentrations are largely determined by the relative affinities of divalent metal ions for proteins as described by the Irving–Williams series in inorganic chemistry: Mg < Ca < Mn < Fe < Co < Ni < Zn > Cu. Consequently, zinc(II) ions bind much stronger to proteins than transition metal ions such as iron(II) and manganese(II) or alkaline earth metal ions such as Mg(II) and Ca(II). The total cellular zinc concentrations are rather high, i.e. hundreds of micromolar. Cellular buffering of zinc results in free zinc(II) ion concentrations in the range of tens to hundreds of picomolar (often given as the “zinc potential”, pZn = −log[Zn2+] = 10–11) (Colvin et al. 2010). These concentrations are commensurate with the affinities of zinc(II) ions for cytosolic zinc-requiring metalloproteins, which are picomolar or lower (Maret and Li 2009). Accordingly, reported micromolar zinc inhibition of cytosolic enzymes is not physiologically significant because the free zinc(II) ion concentrations are the determining factor and not the total zinc concentrations.

There is renewed interest in the question of how zinc modulates protein function because zinc(II) ions are released both inter- and intracellularly (Haase and Maret 2010; Taylor et al. 2012). None of the targets of the released zinc(II) ions has been characterized structurally. These recent developments, in particular quantitative data about cellular zinc(II) ion concentrations, the control of cellular zinc homeostasis, and the role of zinc(II) ions as cellular signalling ions, led us to re-examine the structure and function of putative regulatory zinc sites in proteins.

Intracellular zinc-binding sites

Because of their relatively strong interactions with the side chains of Asp, Glu, Cys, and His, zinc(II) ions are recognized as inhibitors of many enzymes, and they have been employed widely in protein purification and crystallization. In search for enzymes that are strongly zinc-inhibited, several were found to be inhibited much tighter than reported (Maret et al. 1999). Many, but not all of them, contain a catalytic cysteine residue, e.g. caspases, protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), aldehyde dehydrogenases, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Zinc at nanomolar concentrations inhibits these enzymes. Among the ones investigated, caspase-3 was found to be inhibited the strongest with 50 % inhibition at concentrations below 10 nM zinc (Maret et al. 1999).

There are multiple experimental issues in measuring the affinity of inhibitory zinc(II) ions and in defining the structures of inhibitory sites. Most of the enzymes that rely on a catalytic cysteine are stored in buffers containing both a reducing agent and a chelating agent to preserve their activities. For assaying zinc inhibition, these agents must be removed. Thiols bind metal ions and can be replaced with the reducing agent triscarboxyethylphosphine. The enzymatic assay to detect zinc inhibition has to be sufficiently sensitive to perform measurements at enzyme concentrations near or below the inhibition constants. Zinc(II) ion concentrations cannot be readily controlled below nanomolar concentrations unless metal-buffering agents are employed. The zinc content of buffers and other reagents, the zinc concentrations of chelating and reducing agents, and the pH all need to be known. Without control of these parameters unexpected results can be obtained: either zinc ions are found in 3D structures of proteins when none are expected or inhibitory zinc ions are absent in 3D structures despite of experimental evidence for zinc inhibition.

Initially, IC50 values of 200 nM for zinc inhibition of human T cell phosphatase and 15 nM for human PTP-1B were obtained (Maret et al. 1999; Haase and Maret 2003; Krezel and Maret 2008), much lower than values reported previously. However, these values are based on activity assays that are usually performed above the K m value for the substrate to attain maximum velocities. If the substrate and zinc compete for the same site, there will be significant competition at high substrate concentrations and the measured K i value will be quite different from the true K i value. In the case of human receptor PTP β, an inhibition analysis at varying concentrations of both substrate and zinc gave a K i of 21 pM (pH 7.4) for zinc (Wilson et al. 2012). The inhibition is competitive, indicating binding of zinc in the active site containing the catalytic cysteine (residue 1094). Additional ligands of zinc could be an aspartate (1870) and/or a histidine (1871) located on the conformationally flexible WPD loop.

In order for zinc to bind strongly, there must be several zinc-binding ligands in the active site. Fortuitously, there is information on the structures of zinc inhibitory sites in other enzymes to indicate how zinc binds in their active sites (Table 1).

Table 1.

Structurally characterized mononuclear inhibitory zinc sites in enzymes

| Enzymes | Zinc coordination | RCSB PDB |

|---|---|---|

| Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase | His-172, Cys-273a | 2CI7 |

| PRRSV protease Nsp1α | Cys-70, Cys-76, His-146, COOH of Met-180 | 3IFU |

| Cathepsin S | Cys-25, His-164b | 2HH5 |

| Caspase-6 | Lys-36, Glu-244, His-287c | 4FXO |

| His-121, Glu-123, Cys-163 | ||

| Caspase-9 | His-237, Cys-239, Cys-287 | – |

| Glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Lys-204, Asp-260d | 1X0V |

| Phosphoglucomutase (cadmium) | Ser-116, Asp-287, 289, 291 | 1LXT |

| Aconitase | His-692, Asp-695, His-717e | – |

| Ornithine transcarbamoylase | His-168, Cys-303f | 1EP9 |

| Angiogenin-2 and -3 | Asp-41 (Glu-41 in Ang-3), His-82g | 3ZBV/3ZBW |

| Trypsin | His-57, Ser-195h | 1C2E |

| 3C proteases from Coxsackie, Corona and SARS viruses | His-40(41), Cys-144(145, 147)i | 2ZTX |

aAnd three water molecules, two of which are held in place by Glu-77 and Asp-78

bAnd a nitrogen from the inhibitor and a chloride ion

cAnd a water molecule

dInferred as metal ligands from the apostructure of the human enzyme

eNo RCSB PDB entry but the structure is discussed (Costello et al. 1997)

fInferred as metal ligands from the apostructure of the human enzyme

gHis-113 from the catalytic triad binds from a symmetry-related molecule in Ang-2, and two water molecules

hAnd two nitrogen atoms from the inhibitor

iAnd two sulfur atoms from the inhibitor

Zinc inhibits bovine dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (isoform 1) with a K i of 4 nM (pH 7.4) (Knipp et al. 2001). In the protein crystals at pH 9, the zinc(II) ion is bound to the catalytic Cys-273 and His-172. The active site also contains Asp-78 and Glu-77, which are involved in hydrogen bonding to two water molecules that are also ligands of zinc. A third water molecule is held in place by hydrogen bonding to His-172 yielding an overall coordination of the type SNO3 (Frey et al. 2006).

The crystal structure of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) protease Nsp1α revealed a zinc(II) ion in the active site (Sun et al. 2009). The donor set is S2NO2 with Cys-70, -76, His-146, and two oxygen atoms of the carboxy group of the C-terminal Met-180 as ligands. Cys-76 and His-146 form the catalytic dyad. The investigators did not add any zinc during crystallization of the protein. They do not comment on the significance of finding zinc in the active site for the enzymatic activity.

Many cathepsins are also cysteine proteinases. Zinc(II) ions inhibit human cathepsin B very tightly with an IC50 value of about 160 nM (pH 7.4) (Hao et al. 2007). A complex of cathepsin S with the sulfone derivative of an arylaminoethyl amide contains a zinc(II) ion in the active site. Zinc is bound to the catalytic Cys-25, His-164, a chloride ion, and a nitrogen atom from the inhibitor resulting in an SN2Cl coordination (Tully et al. 2006). The protein crystals were grown in 0.2 M zinc acetate. The investigators consider the presence of zinc not important for the inhibition of the enzyme by the synthetic compounds. However, the assay and co-crystallization conditions are most likely significantly different as the enzyme was assayed in 100 mM sodium acetate pH 5.5 while the crystallization was performed in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH not reported). A structure in the absence of zinc (RCSB PDB 2HHN) was also reported. It was obtained after the crystals were soaked with 4 mM dithiothreitol to reduce the catalytic cysteine. In fact, dithiothreitol is a rather strong chelating agent and therefore is expected to remove zinc from the enzyme.

Another family of cysteine proteinases are caspases. Zinc inhibition of caspase-3 was noted with a K i value of about 100 nM (Perry et al. 1997), but the inhibition occurs with an IC50 of <10 nM zinc (Maret et al. 1999). The compound PAC-1 binds zinc with a K d of 42 nM and activates procaspase-3 by removing the inhibitory zinc(II) ions (Petersen et al. 2009). Caspase-6 is also an executioner caspase. Zinc inhibits the human enzyme allosterically at a site involving Lys-36, Glu-244, and His-287 as ligands with a K i of 150 nM (pH 7.5) (Velazquez-Delgado and Hardy 2012). When zinc binds to the allosteric site and locks the enzyme in the helical conformation, the histidine and cysteine residues in the catalytic dyad are 9 Å apart and hence do not bind zinc. However, when the enzyme adopts the canonical conformation, zinc is thought to bind to the catalytic dyad. Recruitment of the ε-amino group of lysine as a ligand is quite unusual. It may also occur in zinc-inhibited glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, where a catalytic lysine, an aspartate and another lysine are part of the active site (Ou et al. 2006). The enzyme is inhibited with an IC50 of 100 nM, but only at slightly alkaline pH 8.4 (Maret et al. 2001). This pH effect could indicate the ionization of the lysine(s) in the active site. Zinc inhibition of caspase-6 at two sites demonstrates that zinc inhibition of enzymes is more subtle than presently acknowledged and can regulate activity at least at two levels on the same enzyme—without accounting for the interaction of caspases with zinc-binding domains of inhibitory proteins. The zinc inhibition constant of the executioner caspase-9 is 300 nM (pH 7.5). Caspase-9 binds two zinc ions. The model indicates that His-237, Cys-239, both forming the catalytic dyad, and Cys-287 bind one zinc and that His-224, Cys-229, -230 and -272 bind a second zinc (Huber and Hardy 2012). The second site has the characteristics of a structural zinc site. Caspases-3, -6, -7, -8, -9 are all involved in apoptosis and have the catalytic Cys–His dyad, but they differ with regard to the third active site residue possibly involved in metal binding, which is Asp, Glu, or Cys. Based on sequence homology among caspases, the zinc-binding site in caspase-3 comprises His-121, Asp-123, and Cys-163.

Regarding the binding of zinc at active sites, there is at least one other general principle. Zinc inhibits rabbit muscle phosphoglucomutase by binding at a site that is normally occupied by a catalytic magnesium ion. The K i value of the enzyme for zinc is 4 pM (pH 8.5) (Peck and Ray 1971). The 3D structure has been determined with cadmium in the active site. The ligands are three carboxylates from aspartates, each binding monodentate, and the oxygen from the Ser-16 side chain. The free zinc(II) ion concentration in muscle of 32 pM (Ray 1969) indicates that zinc inhibits the enzyme under physiological conditions and that the enzyme needs to be activated by removing the inhibitory zinc.

Zinc(II) ions inhibit human erythrocyte Ca2+-ATPase with a K i of 80 pM (pH 7.4) (Hogstrand et al. 1999). The binding site is not known. Free zinc(II) ion concentrations in human erythrocytes are 24 pM (Simons 1991). Therefore, zinc is expected to inhibit this enzyme at least partially under physiological conditions.

Extracellular and vesicular zinc-binding sites

The situation is quite different for extracellular enzymes and enzymes that are secreted from cells (Maret 2008). Since free thiols are rare in extracellular enzymes, the amino acids involved in metal binding of extracellular proteins are mainly glutamate (aspartate) and histidine. Some subcellular vesicles have relatively high free zinc(II) ion concentrations. Micromolar zinc(II) ion concentrations inhibit bovine carboxypeptidase A at a second zinc-binding site next to the catalytic zinc (K i = 0.5 μM). Zinc also inhibits serine proteases such as kallikreins with inhibition constants ranging from 10 nM to about 10 μM. In the case of carboxypeptidase A, the inhibitory zinc binds to only one protein ligand (Glu-270) but is also held in place by a hydroxy bridge to the catalytic zinc ion. In the kallikreins, the zinc ligands are either two histidines or a histidine and a glutamate. A third ligand may further stabilize the zinc/protein interaction. A case can be made for physiological significance of these interactions because some kallikreins are found in seminal and prostatic fluids, which contain about 10 mM zinc. Presumably, the inhibitory zinc dissociates when these enzymes are secreted and diluted. Secreted zinc(II) ions are also involved in intercellular zinc signalling. Zinc(II) ions released into the synapse from zinc-rich neurons inhibit the N-methyl d-aspartate receptor postsynaptically. The inhibition constant is <10 nM (pH 7.3) (Paoletti et al. 1997).

Bacteria

Whether zinc(II) ion fluctuations are used for biological control in bacteria is not known. Free zinc(II) ion concentrations in bacteria were estimated to be femtomolar based on the sensitivity of zinc-responsive transcription factors (Outten and O’Halloran 2001). Direct measurements, however, suggest that they are not much different from those in Eukarya (Wang et al. 2011; Haase et al. 2013). Escherichia coli adenylosuccinate synthase has a K i of 29 nM (pH 7.7) for zinc, which is a competitive inhibitor for both magnesium and aspartate binding (Kang and Fromm 1995).

Perspectives

In general, metal–protein interactions have been categorized as metalloproteins or metal–protein complexes (Vallee and Wacker 1970). The definition is based on apparent stability constants. In metalloproteins, the metal is so tightly bound that it is not removed during isolation of the protein unless the isolation employs strong chelating agents or acidic pH values. However, this definition is not a way of identifying regulatory zinc sites in cytosolic enzymes as the difference in affinities for zinc between the two categories is very small.

A major role of zinc as an inhibitory ion in biology was discussed about 30 years ago (Williams 1984). At least three different principles now demonstrate how zinc(II) ions inhibit enzymes: inhibition through binding at the active site of enzymes that are not zinc metalloenzymes or are magnesium metalloenzymes, allosteric inhibition, and inhibition of zinc enzymes such as carboxypeptidase by binding of a second zinc(II) ion near the catalytic zinc(II) ion. An inhibitory role may seem counterintuitive as zinc activates proteins in the form of zinc metalloenzymes. However, regulatory activation is generally not considered because zinc enzymes are thought to always contain their metal ion. This tenet is based on the observation that isolated zinc enzymes usually have a full complement of zinc. The issue whether or not the zinc content of zinc metalloenzymes varies dependent on physiological conditions has not been tested rigorously, in particular because zinc proteins are now rarely isolated from their original tissues but instead prepared from heterologous expression systems. Zinc(II) ions may also modulate (activate or inhibit) catalytic activity in co-catalytic zinc sites of zinc enzymes with dinuclear sites.

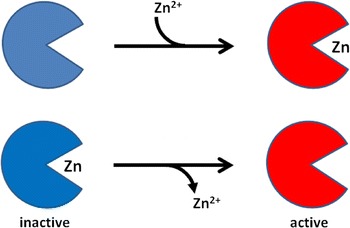

The data and their discussion suggest that enzymes that are not recognized as zinc enzymes because they are kept active in buffers containing chelating agents are indeed zinc enzymes in their inhibited state. The K i values are in the range of the K d values for zinc in zinc enzymes. Active sites of many enzymes contain two metal-binding amino acid side chains, i.e. catalytic dyads of Cys–Cys, His–His, Glu(Asp)–Glu(Asp), Cys–His, Glu(Asp)–His, Cys–Glu(Asp), and sometimes catalytic triads with three of these amino acids. Enzymes such as serine and cysteine proteinases or ribonucleases, e.g. angiogenins (Iyer et al. 2013) (Table 1) are therefore prone to be metal inhibited. From the limited number of structures available (Table 1), the coordination environments of inhibitory sites at the active sites or allosteric sites of enzymes do not appear to differ significantly from the typical ligand environments of catalytic zinc in zinc metalloenzymes except for a tendency for lower coordination numbers in regulatory zinc sites. It appears that zinc binding is employed to keep some enzymes in an inactive state and that they need to be activated by removing the inhibitory zinc(II) ions, i.e. a function opposite from that of catalytic zinc (Fig. 1). One can also argue that the composition of the active sites of many enzymes makes it necessary to control free zinc(II) ions at very low concentrations to avoid wide-spread zinc inhibition at active sites. Therefore, weak interactions of zinc with cytosolic proteins are thought not to be physiologically relevant and reference to free cellular zinc(II) ions as weakly or loosely bound zinc is misleading.

Fig. 1.

Activation and inhibition of enzymes by zinc(II). Apoenzymes are activated by binding of zinc(II) ions to become zinc metalloenzymes (upper). In this article, another mechanism is discussed, namely that enzymes that are not recognized as zinc metalloenzymes masquerade as zinc enzymes in their inhibited state and are activated by removing the inhibitory zinc(II) ions (lower)

With the remarkably low free cellular zinc(II) ion concentrations, it becomes a major challenge to distinguish physiological and pathophysiological significance of zinc inhibitory sites with affinities ranging from micro- to picomolar. Micromolar binding of zinc may be important for extracellular proteins. Cellular zinc is buffered and zinc(II) ion concentrations can fluctuate and reach about 1 nM globally but it is unknown how much they can increase locally (Krezel and Maret 2006; Li and Maret 2009). Above concentrations of about 1 nM they become cytotoxic, indicating the threshold between physiological and pathophysiological concentrations. The description of a structure alone does not prove that the metal site is physiologically relevant.

About 3,000 human proteins are estimated to be zinc proteins based on ligand signatures that define zinc-binding motifs in the amino acid sequences of proteins (Andreini et al. 2006). There is no knowledge on whether or not zinc is regulatory in any of these proteins. Without insight into the structure of regulatory sites, such sites are not accounted for in bioinformatics approaches. Ligands of regulatory (inhibitory) zinc sites cannot be readily identified in the primary sequences of proteins. The reason is that such sites often do not have the relatively short amino acid spacers between the ligands that made the recognition of signatures and prediction of catalytic and structural sites so successful. The active sites of proteins are often made from amino acids that are brought into proximity in the 3D structure but are distant in the primary structure. Thus, the recognition of inhibitory zinc sites faces the same challenges as the identification of active sites in proteins. Therefore, it is impossible to estimate the number of such sites from bioinformatics approaches but it appears that zinc/protein interactions are even more numerous than indicated by the estimate of about 3,000 human proteins. For identification of regulatory sites, several approaches need to be employed and combined, namely quantitative data about binding constants, structural characterizations, investigations of the zinc(II) ion concentrations and their fluctuations in the cell, and correlations with functional outcomes and metabolic effects for zinc-inhibited enzymes such as aconitase (Costello et al. 1997) and ornithine transcarbamoylase (Shi et al. 2001) (Table 1).

Two protein ligands seem to be essential for providing at least micromolar affinities for a zinc(II) ion. In the case of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase, zinc is bound to only two protein ligands but further stabilized through hydrogen bonding of water molecules that are also ligands of zinc. Stabilization afforded by the water ligands seems to lower the affinity by several orders of magnitude. Zinc-binding sites in proteins have been stabilized by employing zinc-binding inhibitors, e.g. by adding two ligands from the inhibitor to the two active site residues in serine proteinases (His, Ser in trypsin) or cysteine proteinases (His, Cys in viral C3 proteinases) to form tetracoordinate zinc complexes (Table 1) (Katz et al. 1998; Lee et al. 2009). It is not known whether regulatory zinc sites in proteins are stabilized in a similar way by forming ternary complexes with biological zinc-binding ligands.

Regulation requires a mechanism for reversible binding of zinc(II) ions to proteins. How reversibility is achieved is not known but metallothionein has been implicated in this process of removing inhibitory zinc(II) ions from proteins (Maret et al. 1999). The reversibility of zinc binding at regulatory sites indicates coordination dynamics associated with conformational changes of the protein similar to mechanisms in transient zinc-binding sites of transporter and sensor proteins (Maret 2011, 2012). For the sake of being comprehensive, coordination dynamics are essential for another mechanism of zinc enzyme inhibition. In metalloproteinases, a fourth zinc ligand, either a cysteine or an aspartate, is employed to keep the enzyme inhibited (Springman et al. 1990; Guevara et al. 2010). Dissociation of the fourth ligand activates the enzyme. Perhaps, a third ligand in inhibitory zinc sites acts as a similar hinge for modulating affinity and making metal association and dissociation in the cell possible.

Our knowledge remains incomplete with regard to the extent of regulation of proteins by reversible zinc binding, the types of principles, the structural details, and the functional implications for metabolism and signal transduction. Such knowledge is critical for understanding the roles of zinc(II) ions in signalling.

Acknowledgments

The work in this laboratory is supported by the BBSRC (Grant BB/K001442/1). I t

hank Prof. Christer Hogstrand (King’s College London) for stimulating discussions.

Abbreviation

- PTP

Protein tyrosine phosphatase

References

- Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. Counting the zinc-proteins encoded in the human genome. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:196–201. doi: 10.1021/pr050361j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auld D. Zinc coordination sphere in biochemical zinc sites. Biometals. 2001;14:271–313. doi: 10.1023/A:1012976615056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin RA, Holmes WR, Fontaine CP, Maret W. Cytosolic zinc buffering and muffling: their role in intracellular zinc homeostasis. Metallomics. 2010;2:306–317. doi: 10.1039/b926662c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello LC, Liu Y, Franklin RB, Kennedy MC. Zinc inhibition of mitochondrial aconitase and its importance in citrate metabolism of prostate epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28875–28881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey D, Braun O, Briand C, Vašák M, Grütter MG. Structure of the mammalian NOS regulator dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. The basis for the design of specific inhibitors. Structure. 2006;14:901–911. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara T, Yiallouros I, Kappelhoff R, Bissdorf S, Stoecker W, Gomis-Rueth FX. Proenzyme structure and activation of astacin metallopeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13958–13965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.097436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase H, Maret W. Intracellular zinc fluctuations modulate protein tyrosine phosphatase activity in insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling. Exp Cell Res. 2003;291:289–298. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase H, Maret W. The regulatory and signaling functions of zinc ions in human cellular physiology. In: Zalups R, Koropatnick J, editors. Cellular and molecular biology of metals. London: Taylor and Francis; 2010. pp. 179–210. [Google Scholar]

- Haase H, Hebel S, Engelhardt G, Rink L. Application of Zinpyr-1 for the investigation of zinc signals in Escherichia coli. Biometals. 2013;26:167–177. doi: 10.1007/s10534-012-9604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Q, Hong S-H, Maret W. Lipid raft-dependent endocytosis of metallothionein in HepG2 cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:428–435. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogstrand C, Verbost PM, Wendelaar Bonga SE. Inhibition of human Ca2+-ATPase by Zn2+ Toxicology. 1999;133:139–145. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(99)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KL, Hardy JA. Mechanism of zinc-mediated inhibition of caspase-9. Protein Sci. 2012;21:1056–1065. doi: 10.1002/pro.2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S, Holloway DE, Acharya KR. Crystal structures of murine angiogenins-2 and-3-probing “structure–function” relationships amongst angiogenin. FEBS J. 2013;280:302–318. doi: 10.1111/febs.12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C, Fromm HJ. Identification of an essential second metal ion in the reaction mechanism of Escherichia coli adenylosuccinate synthase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15539–15544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz BA, Clark JM, Finer-Moore JS, Jenkins TE, Johnson CR, Ross MJ, Luong C, Moore WR, Stoud RM. Design of potent selective zinc-mediated serine protease inhibitors. Nature. 1998;391:608–612. doi: 10.1038/35422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipp M, Charnock JM, Garner CD, Vasak M. Structural and functional characterization of the Zn(II) site in dimethylargininase-1 (DDAH-1) from bovine brain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40449–40456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krezel A, Maret W. Zinc buffering capacity of a eukaryotic cell at physiological pZn. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:1049–1062. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krezel A, Maret W. Thionein/metallothionein control Zn(II) availability and the activity of enzymes. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2008;13:401–409. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0330-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C-C, Kuo C-J, Ko T-P, Hsu M-F, Tsui Y-C, Chang S-C, Yang S, Chen S-J, Chen H-C, Hsu M-C, Shih S-R, Liang P-H, Wand AHJ. Structural basis of inhibition specificities of 3C and 3C-like proteases by zinc-coordinating and peptidomimetic compounds. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7646–7655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807947200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Maret W. Transient fluctuations of intracellular zinc ions in cell proliferation. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:2463–2470. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. Zinc proteomics and the annotation of the human zinc proteome. Pure Appl Chem. 2008;80:2679–2687. doi: 10.1351/pac200880122679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. Metalloproteomics, metalloproteomes, and the annotation of metalloproteins. Metallomics. 2010;2:117–125. doi: 10.1039/b915804a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. Metals on the move: zinc ions in cellular regulation and in the coordination dynamics of zinc proteins. Biometals. 2011;24:411–418. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W. New perspectives of zinc coordination environments in proteins. J Inorg Biochem. 2012;111:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W, Li Y. Coordination dynamics of zinc in proteins. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4682–4707. doi: 10.1021/cr800556u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W, Jacob C, Vallee BL, Fischer EH. Inhibitory sites in enzymes: zinc removal and reactivation by thionein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1936–1940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maret W, Yetman CA, Jiang L-J. Enzyme regulation by reversible zinc inhibition: glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase as an example. Chem Biol Interact. 2001;130–132:893–903. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou X, Ji C, Han X, Zhao X, Li X, Mao Y, Wong L-L, Bartlam M, Rao Z. Crystal structures of human glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 (GPD1) J Mol Biol. 2006;357:858–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outten CE, O’Halloran TV. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science. 2001;292:2488–2492. doi: 10.1126/science.1060331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Ascher P, Neyton J. High-affinity zinc inhibition of NMDA NR1–NR2A receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5711–5725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05711.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck EJ, Ray WJ. Metal complexes of phosphoglucomutase in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:1160–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry DK, Smyth MJ, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Duriez P, Porier GG, Hannun YA. Zinc is a potent inhibitor of the apoptotic protease caspase-3. A novel target for zinc in the inhibition of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18530–18533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen QP, Goode DR, West DC, Ramsey KN, Lee J, Hergenrother PJ. PAC-1 activates procaspase-3 in vitro through relief of zinc-mediated inhibition. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:144–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray WJ. Role of bivalent cations in the phosphoglucomutase system. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:3740–3747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi D, Morizono H, Yu X, Tong L, Allewell NM, Tuchman M. Human ornithine transcarbamoylase: crystallographic insights into substrate recognition and conformational changes. Biochem J. 2001;354:501–509. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons TJB. Intracellular free zinc and zinc buffering in human red blood cells. J Membr Biol. 1991;123:63–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01993964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springman EB, Angleton EL, Birkedal-Hansen H, Van Wart HE. Multiple modes of activation of latent human fibroblast collagenase: evidence for the role of a Cys73 active-site zinc complex in latency and a “cysteine switch” mechanism for activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:364–368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Xue F, Guo Y, Ma M, Hao N, Zhang XC, Lou Z, Li X, Rao Z. Crystal structure of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) leader protease Nsp1α. J Virol. 2009;83:10931–10940. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02579-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KM, Hiscox S, Nicholson RI, Hogstrand C, Kille P. Protein kinase CK2 triggers cytosolic zinc signaling pathways by phosphorylation of zinc channel Zip7. Sci Signal. 2012;5(210):ra11. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully DC, Liu H, Chatterjee AK, Alper PB, Epple R, Williams JA, Roberts MJ, Woodmansee DH, Masick BT, Tumanut C, Li J, Spraggon G, Hornsby M, Chang J, Tuntland T, Hollenbeck T, Gordon P, Harris JL, Karanewsky DS. Synthesis and SAR of arylaminoethyl amides as noncovalent inhibitors of cathepsin S: P3 cyclic ethers. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:5112–5117. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallee BL, Wacker WEC. Metalloproteins. In: Neurath H, editor. The proteins. 2. New York: Academic Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez-Delgado EM, Hardy JA. Zinc-mediated allosteric inhibition of caspase-6. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:36000–36011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.397752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Hurst TK, Thompson RB, Fierke CA. Genetically encoded ratiometric biosensors to measure intracellular exchangeable zinc in Escherichia coli. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16(8):087011. doi: 10.1117/1.3613926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RJP. Zinc: what is its role in biology? Endeavor. 1984;8:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0160-9327(84)90040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M, Hogstrand C, Maret W. Picomolar concentrations of free zinc(II) ions regulate receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase beta activity. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:9322–9326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.320796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]