Viral pathogens such as respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus and influenza virus are the most frequent causes of acute respiratory tract infection and hospitalization in infants and young children. However, no pathogen can be identified in about 30% of suspected respiratory infections [1]. Recently, a new human virus belonging to the Bocavirus genus of the subfamily Parvovirinae was cloned from pooled human respiratory samples and its pathogenic potential was proposed according to its association with respiratory illness [2]. Later studies suggested human bocavirus (HBoV) may be causative for lower respiratory tract disease in young children [3–6]. In this report, we describe the detection by quantitative real-time PCR of HBoV DNA in the nasopharyngeal aspirates of two German children hospitalized for pneumonia. Sequencing of an NP-1 gene fragment and phylogenetic analysis revealed high sequence identity for this HBoV strain compared with the prototype strain HBoV st1 [2] and other strains worldwide [2–6]. Our finding of a high viral load combined with symptoms of acute respiratory tract infection may support the assertion of others that HBoV is an important emerging pathogen [2–6].

In March 2004, a 32-month-old boy presented with a 3-day history of high fever and cough. He was treated with corticosteroids and bronchodilators to control acute bronchoconstriction. No antibiotics were administered. Due to increasing tachypnea and dyspnea, the child was hospitalized. Clinical examination upon admission revealed a body temperature of 39°C, tachypnea and dyspnea, as well as subcostal retractions. Wheezing and dry bilateral fine rales were present upon lung auscultation. Transcutaneously measured oxygen saturation was decreased to 87% and the patient required oxygen supplementation (4 l/min) for 6 days and intravenous treatment with corticosteroids for persistent bronchoconstriction. Laboratory tests showed a leukocyte count of 7.7 × 109/l, a blood pH level of 7.4, base excess of −4.7 mmol/l, and a C-reactive protein value of 5.6 mg/l. Chest radiograph revealed beginning right paracardial pulmonary infiltration without pleural effusion, indicating pneumonia. Under antiobstructive therapy with sultanol and intravenous corticosteroids, the boy’s respiratory condition improved. On day 4 after admission, he developed rotavirus gastroenteritis, probably of nosocomial origin, which rapidly improved under symptomatic therapy. By discharge on day 9, his general condition was good, although a mild fever (38°C) was still present.

In the same period, an 18-month-old boy presented with a 2-day history of increasing dyspnea, fever (39.5°C), and cough. Clinical examination revealed a weakened general condition, tachypnea, a body temperature of 38.8°C, and modest wheezing as well as bilateral basal rales upon auscultation. The patient required oxygen supplementation (2 l/min) for 4 days. Initial laboratory tests showed an elevated leukocyte count of 12.5 × 109/l, a blood pH level of 7.36, base excess of –5.9 mmol/l, and a C-reactive protein value of 21 mg/l. On admission, chest radiograph demonstrated diffuse central and basal infiltrates with pleural effusion in the right costodiaphragmal recessus, indicating pleuropneumonia. Moraxella catarrhalis was cultured, although only in moderate quantities, from nasopharyngeal aspirate together with other resident normal respiratory flora, and antibiotic treatment with ampicillin was started following sensitivity testing. After 4 days of hospitalization, the patient was discharged in good general condition.

To assess the etiology of acute respiratory infection, nasopharyngeal aspirate was recovered from both patients upon admission in a standard volume of buffered saline and, in addition to bacterial culture, analyzed by multiplex PCR for relevant viral and bacterial respiratory pathogens. The panel included respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus (types 1–4), influenza virus (types A and B), coronavirus, reovirus, enterovirus, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis, Bordetella parapertussis, and Legionella pneumophila (http://www.pid-ari.net/). No infectious agent could be detected except for a bacterial culture positive for M. catarrhalis in case 2. Retrospectively, the samples were analyzed by a new quantitative real-time PCR for HBoV DNA developed in our laboratory. PCR primers specific for the viral NP-1 gene and a fluorescence-labeled TaqMan probe were designed on the basis of previously published sequence data [2]: HBoV-UP 5′-AGGAGCAGGAGCCGCAGCC-3′, HBoV-DP 5′-CAGTGCAAGACGATAGGTGGC-3′, HBoV-P 5′-FAM-ATGAGCCCGAGCCTCT CTCCCCACTGTGTC-TAMRA-3′. Amplification was performed using a LightCycler instrument (Roche Applied Science) with a reaction profile of 40°C for 10 min, 95°C for 10 min, 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 30 s, followed by a final cooling step of 40°C for 1 min. Serial dilutions of the linearized plasmid NPSC3.1 were used as a quantification standard and the detection limit proved to be ten copies per PCR reaction, corresponding to 500 viral genomes per ml of source material. Each sample was tested for the presence of inhibitory substances in a parallel reaction and cycle threshold values of the standard used for quantification were monitored. High viral loads (1011 genome equivalents/ml in case 1 and 107 genome equivalents/ml in case 2) were detected in the samples of both patients; specificity was confirmed by sequencing a 354-bp fragment of the NP-1 gene using primers described previously [2]. The sequences obtained (GER 327-05 and GER175-04) were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm with sequences retrieved from GenBank for the HBoV prototype strain st1 as a reference (DQ000495) and further sequences from Japan (DQ296620, DQ296618), Jordan (AB243570, AB243569, AB243568), Canada (DQ267761) and France (AM109963).

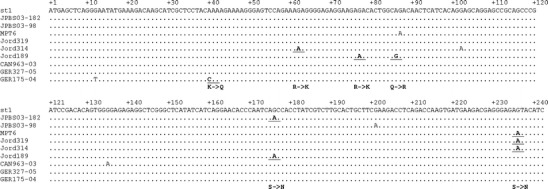

Alignment revealed high conservation of the HBoV genome, since only a few single base-pair substitutions were observed among the selected sequences (Fig. 1). GER 327-05 (GenBank accession number DQ513331) was 100% identical to the reference strain HBoV st1, whereas GER175-04 (GenBank DQ513330) had two nucleotide substitutions (99.2% identity on the nucleotide level): 9G to T without amino acid change and 39A to C resulting in an amino acid exchange (Lys to Glu; 98.8% identity on the amino acid level with HBoV st1). These data confirmed the high degree of bocavirus genome stability reported previously [3, 5].

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of HBoV strains. Sequences of a 240-bp fragment of the NP-1 gene of GER327-05 and GER175-04 (GenBank accession numbers DQ513331 and DQ513330) were compared to those of published sequences of HBoV. Nucleotide changes resulting in amino acid substitution are indicated

In both cases described here, a causal relationship between viral infection and clinical symptoms may be supposed. In fact, clinical symptoms were similar and real-time PCR for HBoV DNA indicated high viral loads, while no other viral pathogen was found. In case 2, the bacterial culture was positive for M. catarrhalis, a commensal organism rarely causing lower respiratory tract infections in immunocompetent children. Accordingly, the number of colonies was moderate in this case. Resident normal respiratory flora was also present and C-reactive protein was only slightly elevated. Thus, M. catarrhalis is unlikely to have caused the patient’s severe lung disease.

This brief report describes HBoV detection by real-time PCR in two children hospitalized for lower respiratory tract infection. We suggest that quantification of viral load might be instrumental in elucidating the correlation between virological data and clinical features. Two very recent studies, although retrospective as all previous ones, strongly support the association of the virus with respiratory disease by showing for the first time a zero or very low incidence of HBoV infection among control infants of the same age group [7, 8]. Although this finding argues against the possibility of an asymptomatic HBoV carrier state in the respiratory tract of healthy individuals, the situation in the immunodeficient patient has yet to be clarified, as do other aspects of bocavirus/host interaction. Certainly, future prospective studies are needed to establish the pathogenic potential of HBoV in respiratory tract disease.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by PID-ARI.net grant 01KI9910/2 from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. T. Allander kindly provided the NPSC3.1 plasmid as positive control for bocavirus PCR. We are indebted to our collaborators W. Puppe and J. Weigl for providing multiplex PCR results, as well as O. Haller for continued support. We thank Gudrun Woywodt for excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1.Williams JV. Human metapneumovirus: an important cause of respiratory disease in children and adults. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2005;7:204–210. doi: 10.1007/s11908-005-0036-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allander TM, Tammi T, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12891–12896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sloots TP, McErlean P, Speicher DJ, Arden KE, Nissen MD, Mackay IM. Evidence of human coronavirus HKU1 and human bocavirus in Australian children. J Clin Virol. 2006;35:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bastien N, Brandt K, Dust K, Ward D, Li Y. Human bocavirus infection, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:848–850. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.051424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma X, Endo R, Ishiguro N, Ebihara T, Ishiko H, Ariga T, Kikuta H. Detection of human bocavirus in Japanese children with lower respiratory tract infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1132–1134. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1132-1134.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissbrich B, Neske F, Schubert J, Tollmann F, Blath K, Blessing K, Kreth HW. Frequent detection of bocavirus DNA in German children with respiratory tract infections. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:109–116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kesebir D, Vazquez M, Weibel C, Shapiro ED, Ferguson D, Landry ML, Kahn JS. Human bocavirus infection in young children in the United States: molecular epidemiological profile and clinical characteristics of a newly emerging respiratory virus. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1276–1282. doi: 10.1086/508213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manning A, Russell V, Eastick K, Leadbetter GH, Hallam N, Templeton K, Simmonds P. Epidemiological profile and clinical associations of human bocavirus and other human parvoviruses. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1283–1290. doi: 10.1086/508219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]