Abstract

Objective

To assemble infectious bronchitis virus (IBV)-like particles bearing the recombinant spike protein and investigate the humoral immune responses in chickens.

Results

IBV virus-like particles (VLPs) were generated through the co-infection with three recombinant baculoviruses separately encoding M, E or the recombinant S genes. The recombinant S protein was sufficiently flexible to retain the ability to self-assemble into VLPs. The size and morphology of the VLPs were similar to authentic IBV particles. In addition, the immunogenicity of IBV VLPs had been investigated. The results demonstrated that the efficiency of the newly generated VLPs was comparable to that of the inactivated M41 viruses in eliciting IBV-specific antibodies and neutralizing antibodies in chickens via subcutaneous inoculation.

Conclusions

This work provides basic information for the mechanism of IBV VLP formation and develops a platform for further designing IBV VLP-based vaccines against IBV or other viruses.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10529-015-1973-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Baculovirus, Bronchitis virus, Infectious bronchitis virus, Recombinant spike protein, Spike protein, Virus-like particles

Introduction

Avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), which belongs to gamma-coronavirus genus, contains four structural proteins: the spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins.

The S protein is post-translationally cleaved into two distinct functional subunits: an N-terminal subunit (S1) that is an immunodominant protein carrying epitopes eliciting virus-neutralizing antibodies (Gallagher and Buchmeier 2001); and a membrane-anchored subunit (S2) that is noncovalently attached to S1 having a transmembrane domain that spans the viral membrane and anchors the S protein in the virion (Bosch et al. 2003). Not surprisingly most new vaccine candidates against IBV are S1-targeted (Chen et al. 2010; Shil et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2012). Both M and E proteins are critical factors in virion assembly and budding and interactions between the two seem to be the minimum requirements for coronavirus VLP (virus-like particles) formation (Vennema et al. 1996; Masters 2006; Masters et al. 2006). The S protein, however, is was not essential but is incorporated into VLP by interactions with the M protein when present (Ho et al. 2004; Bosch et al. 2005).

IBV is responsible for an acute and contagious upper-respiratory tract disease in commercial chickens and is a severe economic burden on the poultry industry worldwide. Vaccination with live attenuated or inactivated vaccines is still the most effective way to control IBV. Unfortunately, current vaccines are unable to provide chickens with sufficient protection because of the limitations of traditional vaccines and multiple serotypes of epidemic IBV strains. Consequently, it is essential to find a feasible way for developing a more safe and effective vaccine strategy. Compared with either whole-virus vaccines or recombinant subunit vaccines, VLPs have some prominent advantages to become promising vaccine candidates. As they lack viral genetic material, VLPs are non-infective and thus are safe. Furthermore, VLPs are highly immunogenic due to their structure being similar to authentic viruses with highly repetitive antigenic epitopes (Kushnir et al. 2012). Although there has been some research on coronavirus VLPs, few studies have focused on IBV. Therefore, in this work novel IBV VLPs have been constructed through the co-infection with three recombinant baculoviruses separately expressing M, E and the recombinant S protein containing the S1 subunit fused to the transmembrane domain and the cytoplasmic tail (TM/CT) of S2 subunit. Additionally, as a vaccine to inoculate specific-pathogen-free chickens, the humoral immunity was evaluated.

Materials and methods

Cells and viruses

Sf9 insect cells were cultured in serum-free Sf-900 III SFM at 27 °C. The Massachusetts 41 (M41) strain of IBV was purchased from China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control.

Gene cloning and generation of recombinant baculoviruses

To obtain the recombinant S (rS) gene, S1 and TM/CT fragments of S gene were fused by means of restriction enzyme digestion and ligation (Fig. 1). Then, the rS, M and E genes were individually cloned into transfer vector pFastBac 1 to generate pFB-rS, pFB-M and pFB-E. The construction of these recombinant transfer vectors is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram for construction of the recombinant S gene. The S1 and TM/CT genes were amplified by RT-PCR with primers shown in Supplementary Table 1. The products of S1 and TM/CT genes were digested with BamHI, respectively, and then ligated together to generate the rS gene. Additionally, a linker was inserted between S1 and TM/CT to ensure their own structures and functions. “SS” indicates the signal peptide sequence (amino acid positions 1-16) of IBV M41 S protein. “S1” indicates the S1 subunit (amino acid positions 17-537) of S protein without signal peptide. “TM/CT” indicates the transmembrane domain and the cytoplasmic tail (amino acid positions 1092-1162) of S protein. “Linker” indicates the flexible peptide (–GlyGlySerSer–), among which the coding sequence for “GlySer” is just the recognition sequence of BamHI

The transfer vectors were separately transformed into DH10Bac E. coli cells (Invitrogen) to construct recombinant shuttle plasmids rBac-rS, rBac-M and rBac-E via site-specific transposition. Three recombinant baculoviruses, designated rBV-rS, rBV-M and rBV-E were subsequently generated through lipofectin-mediated transfection. A plaque assay was used to purify and determine the titers of the recombinant baculoviruses. The procedures of transfection and plaque assay were performed according to the manual of baculovirus expression system (Invitrogen).

Analysis of recombinant protein expression

Sf9 cells were respectively infected with the recombinant baculoviruses rBV-rS, rBV-M and rBV-E at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5. Expression of the recombinant proteins was detected by indirect immunofluorescence assay. Subsequently, western blot was performed to further analyze the recombinant proteins in culture supernatants and cell lysates.

Preparation and analysis of virus-like particles (VLPs)

For preparation of VLPs, Sf9 cells were co-infected with the three recombinant baculoviruses at an MOI of 5 for 96 h. The culture media were collected and filtered. The supernatants were ultracentrifuged at 80,000×g for 1.5 h at 4 °C. After the sediments were resuspended in PBS, the solution was further purified by centrifuging at 80,000×g for 5 h at 4 °C through a discontinuous sucrose gradient. Purified VLPs at the interface between 40 and 30 % (w/v) sucrose were collected.

A transmission electron microscope was used to analyze the formation of IBV VLPs. Purified VLPs were loaded onto a carbon-coated copper grid for 5 min, and then negatively-stained with 2 % (w/v) phosphotungstic acid for 1 min. The VLPs were observed under the EM. For further confirmation of the viral proteins presented in these VLPs, Western blot was performed to analyze the VLPs samples.

Chicken immunization

Two groups of 10-day-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chickens (n = 20) were subcutaneously (s.c.) inoculated twice (day 0 and 14) with IBV VLPs or inactivated M41 viruses. The inoculation dose of VLPs or inactivated M41 contained 2 μg S1 proteins. 20 more SPF chickens were immunized with PBS as a negative control. Sera were collected via the jugular vein before initial immunization (day 0) and at 14 days after each immunization (day 14 and 28) for analysis.

Detection of the antibodies in chicken sera

To determine the IBV-specific antibody levels in sera (day 0, 14 and 28) with an indirect ELISA, the inactivated M41virosomes were used as coating antigen. Sera samples were diluted at 1:80 with PBS containing 5 % (v/v) skimmed milk. HRP-conjugated donkey anti-chicken antibody was used as the secondary antibody. Moreover, IBV-neutralizing antibody titers in sera (day 28) were detected by a virus neutralization test performed on chicken embryos. Sera samples were heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 min and then two-fold serially diluted. Diluted sera were incubated with 102 EID50 of IBV M41 viruses at 37 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, the mixture was inoculated into 9-day-old SPF chicken embryos.

The data among groups were statistically analyzed by Student’s two-tailed t test. p values less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Expression of recombinant proteins in Sf9 cells

The results were shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

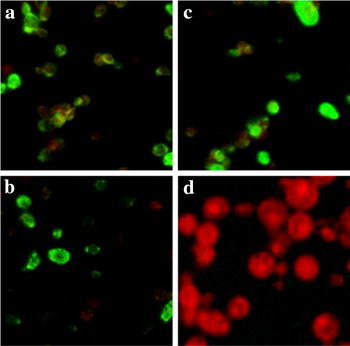

Fig. 2.

Expression of rS, M and E proteins in Sf9 cells detected by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA). a, b and c indicate Sf9 insect cells individually infected with rBV-rS, rBV-M and rBV-E. d shows negative control cells infected with wild type baculoviruses (wBV). An indirect immunofluorescent assay was used to analyze the foreign proteins with chicken-derived anti-IBV hyperimmune serum (China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control) at 3 days post-infection. FITC-conjugated goat anti-chicken antibody was used as the secondary antibody, and the cells were negatively stained with Evans blue. Expression of rS, M and E proteins was indicated by the specific green fluorescence

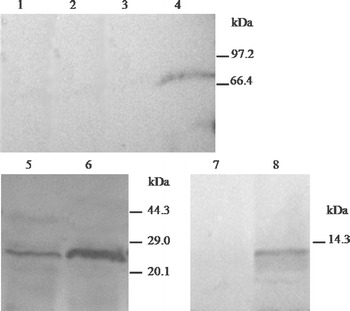

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of rS, M and E proteins in culture supernatants and cell lysates. Lanes 1 and 2: culture supernatants and cell lysates from negative control cells infected with wBV. Lanes 3, 5 and 7: western blot analysis of the supernatants from cells infected with rBV-rS, rBV-M and rBV-E, respectively. Lanes 4, 6 and 8: western blot analysis of the lysates from cells separately infected with rBV-rS, rBV-M and rBV-E. Chicken-derived anti-IBV hyperimmune serum and HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-chicken antibody were used to conduct western blot. Three separate bands of approximately 67, 25 and 12 kDa corresponding to the molecular weight of rS, M and E proteins were detected in the cell lysates, while only one specific band corresponding to M protein was detected in the supernatant samples, which may demonstrate that M protein could be secreted to extracellular space when expressed alone

Characterization and analysis of VLPs

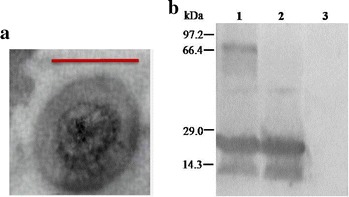

Electron microscopy of the visible VLPs was shown in Fig. 4a and the results of further analysis were shown in Fig. 4b.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of IBV VLPs. a Electron microscopy analysis of VLPs. The formation of IBV VLPs from Sf9 cells co-infected with rBV-rS, rBV-M and rBV-E was examined by an electron microscope after the VLPs-included culture media were purified by ultra-centrifugation with a discontinuous sucrose density gradient. The visible VLPs were similar to authentic IBV particles in size and spherical morphology. Bar = 100 nm. b Western blot analysis of VLPs. Lane 1: purified VLPs samples. Lane 2: purified culture media from cells co-infected by rBV-M and rBV-E with the only difference that rBV-rS was absent. Lane 3: negative control samples from cells infected with wBV. Chicken-derived anti-IBV hyperimmune serum was used to detect the viral proteins. The results demonstrate that when rS and E proteins are co-expressed with M protein, all the three viral proteins can be detected in culture media by the formation of VLPs. In addition, the total protein concentration of purified VLPs samples was determined by a modified Bradford protein assay kit; and the amount of rS protein presented in the VLPs samples was estimated by densitometry of Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel with BSA as standard (data not shown). The percent of rS protein in the VLPs was calculated as 28.4 % (w/w)

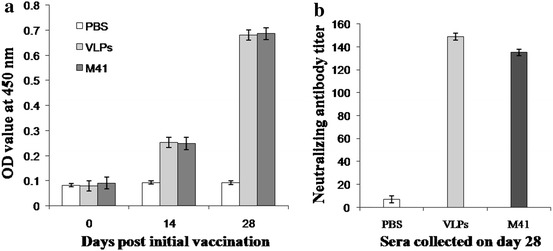

Evaluation of IBV-specific antibodies and neutralizing antibodies

The results demonstrate that the VLPs are competent to induce significant IBV-specific antibodies and neutralizing antibodies in chicken via s.c. administration. Further details are shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

IBV-specific antibodies and neutralizing antibodies detected in chicken sera. a IBV-specific antibody titers in sera (day 0, 14 and 28) were analyzed by indirect ELISA. Some higher but not statistically different levels of IBV-specific antibody titers were detected both in VLPs and the inactivated M41 groups after the initial vaccination (day 14) as compared to the control group (p > 0.05). The antibody titers of the two experimental groups increased notably after the booster vaccination (day 28) and were very significantly higher than that of the control group (p < 0.01). In addition, the levels of antibody titers in chickens that after the booster vaccinated with VLPs and inactivated M41 viruses were significantly higher in contrast to that after the initial vaccination (p < 0.05). Data represent the mean antibody titer ± SD for 20 chickens. b IBV-neutralizing antibody titers detected in sera. After booster vaccination (day 28), the neutralizing antibody titers in each group of chickens were detected by a virus neutralization test performed on chicken embryos. IBV VLPs were competent to elicit considerable neutralizing antibodies comparable to that of the inactivated M41 viruses, and the antibody titers of the both groups were significantly higher in contrast with that of the negative control group (p < 0.01). Neutralizing antibody titer was calculated as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution that neutralized 50 % of 102 EID50 of viruses in SPF chicken embryos

Discussion

Most research concerned with the construction of coronavirus VLPs tend to support the view that the interactions between the M and E proteins are the minimum requirements for the efficient formation of VLPs (Ho et al. 2004; Hsieh et al. 2005). While the S protein is dispensable, it can be incorporated when present. However, there are still some controversies concerning the mechanism of coronavirus VLPs formation although it widely accepted that the existence of the major antigen is critical for the successful design of a genetic-engineered vaccine. In view of these considerations, IBV VLPs were assembled through co-infection with three recombinant baculoviruses separately encoding M, E or the recombinant S genes.

A recombinant S protein was used in current research rather than the traditional whole S protein, as a consequence of the following considerations. The S1 protein is sufficient to elicit good protective immunity against IBV (Cavanagh 2007; Lin et al. 2012). The incorporation of coronavirus S protein into VLPs is closely related to the interactions between the TM/CT domain of S protein and the CT domain of M protein, (de Haan et al. 1999; Bosch et al. 2005). In addition, the heterologous expression of the full-length S protein is difficult as it is a large protein (180 kDa) with intensive hydrophobicity and is highly glycosylated. Accordingly, a recombinant S protein was constructed with a flexible peptide inserted between the two elements to keep their own structures and functions. Moreover, it would be convenient to replace the S1 subunit with other foreign epitopes or target molecules when exploiting this newly establised VLP as an universal platform.

There are two main strategies commonly used to produce VLPs composed of more than one structural proteins in insect systems: co-infection and co-expression (Sokolenko et al. 2012). However, the former was the more accepted strategy in the current study because co-infection is flexible for further comprehensive studies on the molecular and dynamic mechanism of VLP formation. In addition, the present study demonstrated that IBV VLPs could elicit robust humoral immune responses in specific-pathogen-free chickens that were comparable to the inactivated M41 viruses. More importantly, after booster vaccination, the VLPs even induced slightly higher neutralizing antibody titers than the inactivated M41 viruses (p > 0.05). This was mainly due to the S1 subunit that was carrying most of the neutralizing epitopes, and part of S proteins in M41, had lost their native structures during inactivation. This result further confirmed the incorporation of the modified S protein in VLPs.

In conclusion, IBV VLPs composed of rS, M and E proteins were produced in Sf9 insect cells and the humoral immune responses in chicken have been investigated. The findings demonstrate that the modified S protein is sufficiently flexible to retain the ability to self-assemble into VLPs. The VLPs may serve as a promising strategy to control IBV. This work provides basic information for the mechanism of IBV VLP formation and develops a platform for further design of IBV VLP-based vaccines against IBV or other viruses.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Chinese National Programs for High Technology Research and Development (2011AA10A209), Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System (CARS-41-K09), Applied Basic Research Program of Sichuan Province (2013JY0027), Basic Condition Platform Project of Science and Technology of Sichuan Province (14010136), and Natural Science Foundation of China (31302094).

Supporting information

Supplementary Table 1—Primers used in this work.

Supplementary Figure 1—Schematic diagram for construction of the transfer vectors. pFB-rS encoding rS gene, pFB-M encoding M gene, pFB-E encoding E gene. The rS, M and E genes were under the control of PPH, individually.

Footnotes

Peng-wei Xu and Xuan Wu have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Peng-wei Xu, Email: mengzhonren@163.com.

Xuan Wu, Email: 1109453509@qq.com.

Hong-ning Wang, Phone: 86-28-8547-1599, Email: whongning@163.com.

Bing-cun Ma, Email: 412744272@qq.com.

Meng-die Ding, Email: dingmengdie1987@126.com.

Xin Yang, Email: 6682631@qq.com.

References

- Bosch BJ, van der Zee R, de Haan CA, Rottier PJ. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J Virol. 2003;77:8801–8811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch BJ, de Haan CA, Smits SL, Rottier PJ. Spike protein assembly into the coronavirion: exploring the limits of its sequence requirements. Virology. 2005;334:306–318. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh D. Coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. Vet Res. 2007;38:281–297. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HY, Yang MF, Cui BA, Cui P, Sheng M, Chen G, Wang SJ, Geng JW. Construction and immunogenicity of a recombinant fowlpox vaccine coexpressing S1 glycoprotein of infectious bronchitis virus and chicken IL-18. Vaccine. 2010;28:8112–8119. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan CA, Smeets M, Vernooij F, Vennema H, Rottier PJ. Mapping of the coronavirus membrane protein domains involved in interaction with the spike protein. J Virol. 1999;73:7441–7452. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7441-7452.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher TM, Buchmeier MJ. Coronavirus spike proteins in viral entry and pathogenesis. Virology. 2001;279:371–374. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y, Lin PH, Liu CY, Lee SP, Chao YC. Assembly of human severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like particles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:833–838. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh PK, Chang SC, Huang CC, Lee TT, Hsiao CW, Kou YH, Chen IY, Chang CK, Huang TH, Chang MF. Assembly of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus RNA packaging signal into virus-like particles is nucleocapsid dependent. J Virol. 2005;79:13848–13855. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.13848-13855.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir N, Streatfield SJ, Yusibov V. Virus-like particles as a highly efficient vaccine platform: diversity of targets and production systems and advances in clinical development. Vaccine. 2012;31:58–83. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KH, Hsu AP, Shien JH, Chang TJ, Liao JW, Chen JR, Lin CF, Hsu WL. Avian reovirus sigma C enhances the mucosal and systemic immune responses elicited by antigen-conjugated lactic acid bacteria. Vaccine. 2012;30:5019–5029. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters PS. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 2006;66:193–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters PS, Kuo L, Ye R, Hurst KR, Koetzner CA, Hsue B. Genetic and molecular biological analysis of protein-protein interactions in coronavirus assembly. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;581:163–173. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-33012-9_29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shil PK, Kanci A, Browning GF, Markham PF. Development and immunogenicity of recombinant GapA(+) Mycoplasma gallisepticum vaccine strain ts-11 expressing infectious bronchitis virus-S1 glycoprotein and chicken interleukin-6. Vaccine. 2011;29:3197–3205. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolenko S, George S, Wagner A, Tuladhar A, Andrich JM, Aucoin MG. Co-expression vs. co-infection using baculovirus expression vectors in insect cell culture: benefits and drawbacks. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30:766–781. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennema H, Godeke GJ, Rossen JW, Voorhout WF, Horzinek MC, Opstelten DJ, Rottier PJ. Nucleocapsid-independent assembly of coronavirus-like particles by co-expression of viral envelope protein genes. EMBO J. 1996;15:2020–2028. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.