The detection of respiratory viruses in many prospective clinical studies has relied upon detection with standard laboratory assays, such as antigen detection, viral culture, or serology. Data describing the relative importance of community-acquired respiratory viruses, such as rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus (HMPV) [1], and newly described human coronavirus (HCV) subtypes [2], which are not detectable by these standard assays, in healthy young children who are not admitted to the hospital is limited.

We developed a novel respiratory real-time reverse transcription (RT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel to detect the presence of HMPV, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza virus (PIV) 1, 2, and 3, adenovirus, human coronaviruses Group 1 (229E and NL63) and Group 2 (OC43 and HKU1), and rhinovirus. We conducted a one-year prospective outpatient community-based study of respiratory tract infections (RTIs) in a healthy infant cohort. Our goals were to determine the proportion of viral RTIs caused by these 13 viruses in symptomatic but otherwise healthy infants, as well as to characterize the clinical features of the identified viral infections and quantify the decline in viral load of patients infected with HMPV in this outpatient population.

This cohort surveillance study in a population of healthy infants followed for 13 months was conducted between 1 April 2004 and 1 May 2005. Infants between the ages of 0–6 months were enrolled from the Well Child Clinic at the Madigan Army Medical Center (MAMC) in Tacoma, WA. All subjects were evaluated at each RTI visit by one of three study physicians. Infections were determined to be lower RTIs if bronchiolitis or pneumonia were diagnosed clinically or radiographically by a study physician. We also assessed the presence of a secondary infection requiring antibiotics.

During the 13 months of the study, parents called for an appointment in our study clinic if their infant had any respiratory tract symptoms. The clinical data obtained at the study visits for RTIs and by phone follow-up included the duration and complications of the illness, and missed days of work or daycare. Those infants with new onset of at least 2 of 5 respiratory tract symptoms (cough, rhinorrhea, wheezing, fever, and nasal congestion) had a physical examination performed, and respiratory secretions sampled with a nasal swab of the posterior nasal pharynx using Dacron flocked swabs with a nylon shaft (Copan Diagnostics, Corona, CA).

The swab was rinsed in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer using previously described techniques [3] and was then discarded. The buffer containing the specimen was stored for up to 72 h at room temperature prior to transport to the University of Washington Virology Laboratory at the Seattle Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center. Previous testing had demonstrated that respiratory viral RNA was stable at room temperature in this buffer solution for up to one week. Total nucleic acid was extracted from 200 μL of lysis buffer as described for nasal washes [3] and tested for HMPV, RSV, PIV 1, 2, and 3, influenza A and B, rhinovirus, human coronaviruses Group 1 (229E and NL63) and Group 2 (OC43 and HKU1), and adenovirus by real-time RT-PCR using previously described techniques [4, 5]. Samples from infants who had HMPV detected had quantification of the viral loads performed, with a repeat nasal swab obtained 7–10 days after the initial sample.

All data was analyzed using STATA 8.0 (College Station, TX). Frequency rates were calculated for all of the study viruses. Descriptive analysis was performed to evaluate the demographic characteristics of the study population. Univariate analyses were performed to assess the associations between demographic and clinical characteristics and infection with study viruses. All comparisons were done using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate for contingency tables. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Ninety-two infants were enrolled in the study. Ten subjects did not complete the study, leaving a total of 82 evaluable subjects. The mean age at enrollment was 2.1 months (range 0–6 months), and only 16 (19.5%) of the subjects attended full-time daycare. Tobacco use was admitted in seven (8.5%) households and older siblings were present in 41 (50%) households.

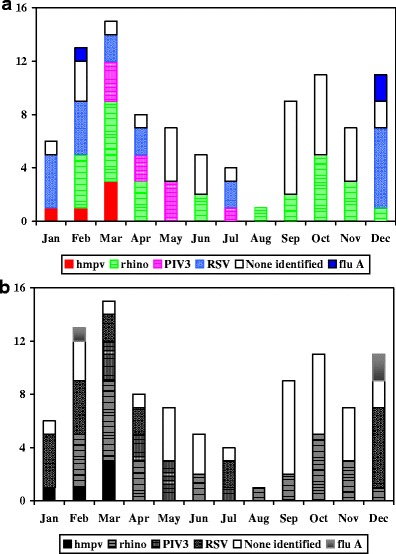

Of the 99 episodes evaluated, there was a mean of 1.2 RTI/subject/year (range 0–6). Study viruses were identified in 57 of the 99 episodes (57.6%). The most common viruses were RSV (20/57, 35%) and rhinovirus (26/51, 51%). There were two cases of adenovirus, but human coronaviruses, influenza B, and PIV 1 and 2 were not detected at all. Respiratory viruses were most likely to be detected in the winter and the spring (Fig. 1). Dual infections peaked in March (3/7, 43%). Rhinovirus was the most common pathogen to be found in a dual infection (5/7, 71%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Commonly identified respiratory viruses in young children with respiratory symptoms. The x-axis represents the month and the y-axis the number of infections identified for each virus

Rhinovirus, followed by RSV and PIV 3, were the most frequently identified viruses associated with upper respiratory tract disease. Subjects with lower respiratory tract disease, 26/99 (26%) cases, were most commonly infected with RSV and rhinovirus. When identified in a lower RTI, rhinovirus predominantly occurred as a co-infection (4/7, 57%). Overall, viral co-infections were significantly more likely than single-virus infections to result in lower tract disease (p < 0.01) (6/7 (86%)). Fever was more often present in lower RTIs with an identified virus (12/19, 63%) than in those without a pathogen (2/7, 29%). HMPV closely resembled RSV in clinical presentation. However, the duration of illness for HMPV was significantly longer than for RSV (p < 0.01).

Antibiotics use was more common in HMPV infections (4/5, 80%, p < 0.01) than with all of the other study viruses combined. Three of the HMPV-infected children were diagnosed with otitis media and one with otitis and pneumonia. The only hospitalizations occurred in children infected with RSV (1/20; 5%) and PIV 3 (1/9; 11%).

The measurement of viral load in the five HMPV-infected subjects revealed the mean peak viral load to be 106 copies/ml during the first week of the illness. Sequential testing demonstrated a mean 3 log drop in viral load by the end of the second week in 80% of subjects.

Our study provides additional evidence that rhinovirus is the most common viral pathogen detected during acute respiratory tract disease in very young children who had respiratory disease identified by their parents in their homes. Rhinovirus was, additionally, the most common co-pathogen in dual infections. Our study also corroborates the heightened importance of rhinovirus as a factor in lower RTIs, as recently described by Legg et al. [6], and the growing recognition of rhinovirus as an important pathogen in children, especially children <1 year of age [7] and children less than 5 years of age [8].

Our study agrees with other studies describing a lower frequency of HMPV infection as compared to RSV [9]. Our data also demonstrated a duration of HMPV shedding of at least 7–10 days, followed by a substantial drop in viral load. This suggests that the virus peaks during the first week of the illness, and, therefore, may have implications for infection control practices. We were also able to quantify the HMPV viral load by using weekly nasal swabs and real-time RT-PCR methods. We believe that the data presented here are unique to address the serial quantitative viral load associated with HMPV infection. By looking at repeated viral loads during an acute illness and showing a significant drop in levels over time, it may suggest a decrease in infectivity specifically for HMPV. The same data also suggests that, similar to RSV, young children could have a sufficient amount of virus to be potentially contagious even after 2 weeks of infection.

We did not detect any human coronavirus in our patients, in contrast to a recent study using the same PCR methods in a children’s hospital-based setting conducted during the same time period. In this hospital-based study evaluating children from all age groups, coronaviruses were detected in 66/1,043 (6.3%) pediatric patients with acute RTI [4]. However, the patients in this hospital-based study were more seriously ill, as based on the fact that they were hospitalized or seen in the emergency department, and were also more likely to have underlying chronic diseases. These findings suggest that, perhaps, some coronavirus subtypes may be less prevalent in a healthy community cohort of young infants.

Our study is also unique in that a simple sampling and transport method was developed permitting obtaining swabs in a primary care setting and storage and transport of the noninfectious RNA and DNA in a stable viral lysis buffer at room temperature. Previous studies that we have conducted have required the careful monitoring of temperature and expensive methods of transport on ice from the primary care clinic to the reference laboratory. The methods described in this study take advantage of improved types of nasal swabs and direct inoculation into the transport lysis buffer without dilution or potential contamination in viral transport media, and are suitable for viral epidemiology studies in areas where ice or immediate transportation are not available.

Our study may have had an underrepresentation of RTIs, since we relied on the parents of subjects to contact us. However, the illnesses that we missed were likely to have been of decreased severity, since our cohort of military dependents depend on the free and readily available medical care that we provide and do not have access to care at any other medical facility. In addition, we had a low rate of daycare attendance, which could have contributed to this low rate of RTIs.

In conclusion, rhinovirus was the most common cause of RTIs and co-infected RTIs in our healthy outpatient cohort of infants. RSV and rhinovirus were most commonly associated with lower RTIs, and human coronavirus was not detected as a pathogen in this setting. HMPV infection was less common than RSV infection as a cause of community-acquired respiratory disease in these healthy infants, but HMPV infection appeared to be an important contributor to antimicrobial use. We utilized newly available quantitative molecular techniques to characterize the relative importance of common and newly identified respiratory viruses in young children in the primary care setting. The knowledge gained in this study may assist health care providers in giving reassurance to parents and can be used to decrease the unnecessary use of antibiotics in this population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Troy Patience, Madigan Army Medical Center, and Emily Martin, Seattle Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, for their assistance in the data analysis.

Abbreviations

- RTI

respiratory tract infection

- RSV

respiratory syncytial virus

- HMPV

human metapneumovirus

Footnotes

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the author(s) and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Defense. The investigators have adhered to the policies for the protection of human subjects as prescribed in 45 CFR 46.

References

- 1.van den Hoogen BG, de Jong JC, Groen J, Kuiken T, de Groot R, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD. A newly discovered human pneumovirus isolated from young children with respiratory tract disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:719–724. doi: 10.1038/89098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Hoek L, Pyrc K, Jebbink MF, Vermeulen-Oost W, Berkhout RJ, Wolthers KC, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, Kaandorp J, Spaargaren J, Berkhout B. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004;10:368–373. doi: 10.1038/nm1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuypers J, Wright N, Morrow R. Evaluation of quantitative and type-specific real-time RT-PCR assays for detection of respiratory syncytial virus in respiratory specimens from children. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuypers J, Martin ET, Heugel J, Wright N, Morrow R, Englund JA. Clinical disease in children associated with newly described coronavirus subtypes. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e70–e76. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuypers J, Wright N, Ferrenberg J, Huang ML, Cent A, Corey L, Morrow R. Comparison of real-time PCR assays with fluorescent-antibody assays for diagnosis of respiratory virus infections in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2382–2388. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00216-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legg JP, Warner JA, Johnston SL, Warner JO. Frequency of detection of picornaviruses and seven other respiratory pathogens in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:611–616. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000168747.94999.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusel MM, de Klerk NH, Holt PG, Kebadze T, Johnston SL, Sly PD. Role of respiratory viruses in acute upper and lower respiratory tract illness in the first year of life: a birth cohort study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:680–686. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000226912.88900.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller EK, Lu X, Erdman DD, Poehling KA, Zhu Y, Griffin MR, Hartert TV, Anderson LJ, Weinberg GA, Hall CB, Iwane MK, Edwards KM, New Vaccine Surveillance Network Rhinovirus-associated hospitalizations in young children. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(6):773–781. doi: 10.1086/511821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams JV, Harris PA, Tollefson SJ, Halburnt-Rush LL, Pingsterhaus JM, Edwards KM, Wright PF, Crowe JE., Jr Human metapneumovirus and lower respiratory tract disease in otherwise healthy infants and children. N Eng J Med. 2004;350(5):443–450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]