Abstract

To provide up-to-date information on the occurrence of Cryptosporidium in pre-weaned calves from Sardinia (Italy), the species implicated and their zoonotic potential, 147 faecal samples from 22 cattle herds were microscopically examined for Cryptosporidium oocysts; positive isolates were molecularly characterised. A questionnaire was developed to identify risk factors for Cryptosporidium infection. Overall, the percentage of positive calves and farms was 38.8 and 68.2%, respectively. The SSU rRNA-based PCR identified two Cryptosporidium species, Cryptosporidium parvum (95.8%) and C. bovis (4.2%). Sequence analyses of the glycoprotein (gp60) gene revealed that all C. parvum isolates belonged to the subtype family IIa (IIaA15G2R1 and IIaA16G3R1), with the exception of three isolates that belonged to the subtype family IId (IIdA20G1b and IIdA20). Mixed logistic regression results indicated that calves aged 15–21 days were more likely to be Cryptosporidium-positive. The risk of being positive was also significantly higher in herds from Central Sardinia and in farms using non-slatted flooring. In addition, the application of disinfectants and milk replacers was significantly associated with higher Cryptosporidium prevalence. In contrast, the risk of being positive was significantly reduced in halofuginone-treated calves. Our results reveal that a significant percentage of suckling calves are carriers of zoonotic subtypes of C. parvum. Thus, both healthy and diarrhoeic calves younger than 1 month may represent a risk for the transmission of cryptosporidiosis in humans and animals.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00436-018-6000-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cryptosporidium, Pre-weaned calves, SSU rRNA genotyping, gp60 subtyping, Italy

Introduction

Cryptosporidium spp. are apicomplexan enteropathogens affecting a broad range of vertebrate hosts (Xiao 2010). They are recognised worldwide as a cause of diarrhoeal disease, particularly in ruminants (de Graaf et al. 1999; Santín and Trout 2008). In cattle, cryptosporidiosis causes serious and economically significant outbreaks of neonatal diarrhoea during calving, related to the deterioration of appetite and state of dehydration, growth retardation and, to a lesser extent, mortality (Sanford and Josephson 1982; Naciri et al. 1999). A number of molecular techniques have shown that cattle can be infected with at least sixteen Cryptosporidium species and multiple genotypes. The four most common and widely distributed Cryptosporidium species in cattle have been shown to be age-related. Thus, Cryptosporidium andersoni, C. bovis and C. ryanae are low-pathogenic and host-adapted species which are especially common in post-weaned and adult cattle (Santín and Trout 2008; Xiao 2010). In contrast, C. parvum is the most frequently detected species in pre-weaned calves. Although asymptomatic C. parvum infections have been found in cattle, this species is significantly related with diarrhoeic syndrome in calves (Sanford and Josephson 1982; Naciri et al. 1999). C. parvum is also an important zoonotic species because together with C. hominis, it is involved in most cases of cryptosporidiosis in humans (Xiao 2010). Given that some recent investigations suggest an increasing importance of C. hominis in bovines (Zahedi et al. 2016; Razakandrainibe et al. 2018), cattle may play an important role as reservoirs of Cryptosporidium species causing human cryptosporidiosis. Cryptosporidial infection is transmitted by the faecal-oral route, and the majority of human cases are waterborne (Fayer et al. 2000; Olson et al. 2004). Thus, it has been suggested that cattle facilities, manure runoffs from beef and dairy feedlots, and spraying of liquid manure on fields may be related to the contamination of water supplies by C. parvum and C. hominis oocysts and thus to a significant proportion of cryptosporidiosis outbreaks in humans (Mohammed et al. 1999; Sischo et al. 2000).

In cattle herds, infected animals, above all diarrhoeic calves, and other livestock acting as reservoirs of the protozoan such as lambs and goat kids may act as sources of direct infection (Olson et al. 2004). In addition, indirect transmission by ingesting environmental oocysts contaminating water and food, as well as bedding, cattle sheds, pasture or soil, has been reported as an important form of bovine transmission (Wells and Thompson 2014). Thus, factors related to the presence of Cryptosporidium infection in cattle farms and consequently favouring the occurrence of neonatal diarrhoea outbreaks are mainly associated with environmental contamination by oocysts, and with the immunological status of calves (Duranti et al. 2009). Poor hygienic conditions, intensive rearing systems, communally housed animals, overcrowded livestock facilities or a high number of newborn calves during the calving season are risk factors for cattle cryptosporidiosis (de Graaf et al. 1999).

Nevertheless, significant differences between studies have been shown, probably related to geographical and management differences, or even to the study design. Thus, regional risk factor surveys should be performed to identify the most decisive variables in a particular cattle population.

Epidemiological studies on the presence of Cryptosporidium spp. in Italian cattle farms are still limited; prevalences ranging from 5 to 11.4% (Merildi et al. 2009; Duranti et al. 2009; Di Piazza et al. 2013) have been reported, although the percentage of positives increases (50–62.1%) when only diarrhoeic calves are considered (Grana et al. 2006; Papini et al. 2018). At least five Cryptosporidium species, including C. bovis, C. ryanae, C. ubiquitum and C. hominis, have been identified in cattle from Italy, but C. parvum was the most frequent species found (Grana et al. 2006; Duranti et al. 2009; Merildi et al. 2009; Imre and Dărăbus 2011; Di Piazza et al. 2013).

There is also a notable presence (approx. 30%) of the protozoan in calves from Sardinia (Scala and Garippa 1994; Scala et al. 2007). However, no information on the Cryptosporidium species present in Sardinian calves has been recorded. We thus carried out a survey in cattle dairy farms of Sardinia, Italy. The aim was to provide up-to-date data on the occurrence of Cryptosporidium spp. in both healthy and diarrhoeic pre-weaned calves, the species implicated and their zoonotic potential, as well as to identify the risk factors associated with hygiene and management.

Materials and methods

Study area and characteristics of studied flocks

The study was performed in Sardinia (38° 51′–41° 18′ N; 8° 8′–9° 50′ E), the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, located to the west of the Italian Peninsula, covering an area of 24,090 km2 (Fig. 1). Sardinia is a major livestock breeding area, particularly for sheep. Cattle breeding is also an important Sardinian farming activity, with 271,083 heads of cattle bred in 2017 (ISTAT 2017). Most of the cattle farms are intensive and located throughout the island. A high density of cattle farms is located in Arborea, an important agro-economical region located in the province of Oristano (western Sardinia) with a substantial production of meat and dairy products and a high genealogy of cattle (Varcasia et al. 2006).

Fig. 1.

Geographic map of the sampling locations in the provinces of Sassari and Oristano (grey areas) of Sardinia (Italy)

Sample collection and microscopic analysis

From February to March 2014, faecal samples were collected directly from the rectum of a total of 147 pre-weaned calves in 22 cattle herds located in the centre (province of Oristano; n = 18) and the north (province of Sassari; n = 4) of Sardinia (Fig. 1). In each farm, all animals younger than 35 days old were sampled. The number of faecal specimens taken ranged from 4 to 13 (mean = 6.68; standard deviation (SD) = 2.41).

A questionnaire requiring no more than 10 min of the farmers’ time was administered regarding general characteristics of the farms, calves’ housing conditions and the hygiene practices probably associated with Cryptosporidium infection risk in cattle herds. All farmers answered the questionnaire at the moment of sampling; it included descriptors of the farm such as herd size, breeding system, type of cattle farming and the presence of other animal species. Detailed information was also gathered on the stalling of calves, type of flooring, drinking water, general hygiene status and the use of disinfectants. Owners were asked about previous diarrhoeic episodes in the farm, vaccination of pregnant dams against other infectious agents causing neonatal diarrhoea, administration of colostrum or use of anti-diarrhoeal compounds in calves. Cattle breed, age and hydration status of each animal were also recorded when sampling.

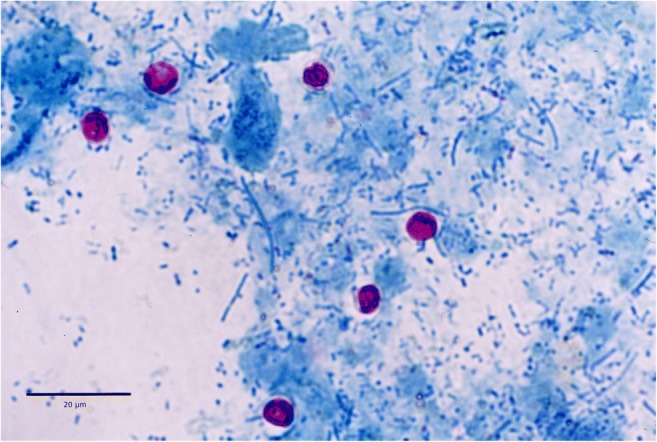

Each faecal specimen was firstly studied macroscopically to establish its consistency as liquid, soft or solid, and the presence of mucus or blood was also noted. Faecal specimens were then examined for the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts by microscopy of stained Ziehl-Neelsen smears (Fig. 2). Infection intensity was estimated semi quantitatively according to the average number of oocysts in 20 fields at × 1000 magnification and expressed as oocysts per field (opf) (Castro-Hermida et al. 2002). All microscopy-positive samples were selected for further genetic characterisation.

Fig. 2.

Cryptosporidium oocysts in Ziehl-Neelsen staining

DNA extraction

Oocysts were purified from faecal specimens by using saturated NaCl solution as previously described (Elwin et al. 2001). Purified oocysts were then resuspended in distilled water and stored at 4 °C prior to use. Total DNA was extracted from 200 μl of oocyst suspensions using the ChargeSwitch® gDNA Micro Tissue Kit (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, preceded by three freezing cycles with liquid nitrogen (1 min) and thawing at 100 °C (5 min). DNA extracts were stored at − 20 °C.

Cryptosporidium species identification and C. parvum subtype analysis

Cryptosporidium species were determined by nested PCR of an SSU rRNA gene fragment and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the secondary PCR products with the endonucleases SspI, VspI and MboII, using primers previously described (Jiang et al. 2005). Species assignment was carried out by comparing RFLP profiles to those reported by Xiao and Ryan (2008). Diagnosis of Cryptosporidium species different from C. parvum was confirmed by DNA sequencing of the SSU rRNA PCR products.

A gp60 gene fragment (800 to 850 bp) was amplified using the nested PCR protocol of Alves et al. (2003) to subtype C. parvum isolates. Those samples testing negative at the gp60 gene were sequenced at the SSUrRNA gene to confirm the PCR-RFLP results. Both selected SSU rRNA and gp60 DNA fragments were purified and sequenced on an ABI 3730xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at the Sequencing and Fragment Analysis Unit of the Santiago de Compostela University. Sequences were aligned and edited using ChromasPro (Technelysium, Brisbane, Australia) and consensus sequences were then scanned against the GenBank database using BLAST. Subtypes were named according to the nomenclature described by Sulaiman et al. (2005). Unique gp60 sequences identified in this study were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MG725620 and MG725621.

Statistical analysis

Variables were categorised for statistical analysis as summarised in Table 1. A mixed effects logistic regression was used for risk factor analysis; herd was considered as a random factor. A geographic variable was also included based on the location of the farm (Oristano or Sassari). Several variables were not included in the analysis since all the farms use private water wells for drinking water and all calves were stalled without dam and fed with colostrum for the first 3 days of life. Milk or a milk replacer was always offered via nipple buckets.

Table 1.

Cryptosporidium positivity in calves from Sardinia. Results for the different categories considering the analysed factors

| Variables | Groups | Positivity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| General characteristics of the farm | ||

| Age | < 8 days (n = 32) | 53.1 |

| 8–14 days (n = 33) | 51.1 | |

| 15 to 21 days (n = 65) | 26.2 | |

| > 21 days (n = 17) | 35.3 | |

| Location | Oristano (n = 109) | 41.3 |

| Sassari (n = 38) | 31.6 | |

| Cattle breed/system of breeding | Frisian/dairy (n = 139) | 38.6 |

| Other (n = 9) | 40.0 | |

| Presence of other animals | Yes (n = 35) | 31.4 |

| No (n = 112) | 41.1 | |

| Stalling of calves | Individual (n = 68) | 35.3 |

| Grouped (n = 79) | 41.8 | |

| Type of flooring | Not slatted (n = 93) | 45.2 |

| Slatted (n = 54) | 27.8 | |

| General hygiene | Bad (n = 53) | 37.7 |

| Good (n = 73) | 39.7 | |

| Very Good (n = 21) | 38.1 | |

| Use of disinfectants | Yes (n = 53) | 47.9 |

| No (n = 94) | 33.3 | |

| Previous diarrhoea outbreaks | Yes (n = 98) | 40.8 |

| No (n = 49) | 34.7 | |

| Vaccination against other enteropathogens | Yes (n = 83) | 34.9 |

| No (n = 64) | 43.8 | |

| Halofuginone | Yes (n = 23) | 13.0 |

| No (n = 124) | 43.5 | |

| Macroscopic characteristics of faeces | ||

| Faecal consistency | Solid (n = 82) | 31.7 |

| Soft (n = 49) | 42.9 | |

| Watery (n = 16) | 62.5 | |

| Presence of mucus | Yes (n = 22) | 36.4 |

| No (n = 125) | 39.2 | |

| Presence of blood | Yes (n = 3) | 33.3 |

| No (n = 144) | 38.9 | |

The frequency of disinfection of calf pens was not included in the analysis since most farmers only disinfect calf pens before putting in a new batch of calves; only in one farm, where four faecal samples were collected, did the owner disinfect calf pens fortnightly. Since C. parvum infection can be asymptomatic or cause diarrhoea in calves, the relationship between the presence of this species and the macroscopic characteristics of faeces (faecal consistency, presence of mucus or blood) was also analysed using the same multivariate test. In both cases, factors were eliminated from the initial model using a backward conditional method based on the AIC value (Akaike Information Criterion) until the best model was built. Next, all pairwise interactions that were biologically plausible were evaluated. Odds ratios were computed by raising e to the power of the logistic coefficient over the first category of each factor (reference category), not over the last.

The existence of significant differences in oocyst excretion intensity considering the macroscopic characteristics of faeces was analysed using ANOVA. Tukey’s HSD test was used to detect differences between pairs. For these analyses, the dependent variable—oocysts per field—was log-transformed beforehand, Ln (opf + 1). In all analyses, associations were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with the glmer () function from lme4 package (Bates et al. 2014) in the R statistical package (R v.3.1.1; R Development Core Team).

Results

Prevalence

Microscopic analysis of 147 faecal samples revealed the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts in 57 (38.8%) specimens (Fig. 2). The mean intensity of oocyst shedding was 3.38 opf (SD = 5.85). Fifteen of 22 cattle farms (68.2%) harboured infected animals; the mean intra-herd prevalence was 51.8%, whereas the percentage of calves shedding oocysts in each positive farm ranged from 20.0 to 85.7%.

Risk factor analysis

Mixed logistic regression results indicated that calf positivity to Cryptosporidium spp. was mainly determined by the animals’ age, farm location, type of flooring and use of disinfectants, halofuginone and milk replacer (Table 2). Thus, calves younger than 2 weeks showed the lowest prevalence values; animals aged 1–7 days presented a 1.6- to 4.6-fold higher probability of being positive to the protozoan than other age groups. The location and type of flooring can also be considered determining factors since the risk of being positive was 4.7- and 6.0-fold higher in herds from Oristano and in farms using non-slatted flooring, respectively. The application of disinfectants and milk replacers was significantly associated with higher Cryptosporidium prevalences (Table 2). In contrast, the risk of being positive to the protozoan was lower (OR = 0.27; 95% CI 0.05–1.06) when calves were treated with halofuginone.

Table 2.

Final outcome of a backward (conditional) mixed logistic regression for risk factor analysis. Factors had been eliminated step by step (AIC) until best model was built

| Estimate | S.E. | p | OR | C.I. 95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Intercept | − 0.947 | 0.909 | 0.297 | 0.388 | 0.059 | 2.187 |

| Age | ||||||

| < 7 days | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7–14 days | − 0.461 | 0.638 | 0.470 | 0.631 | 0.176 | 2.187 |

| 14–21 days | − 1.527 | 0.579 | 0.008 | 0.217 | 0.007 | 0.660 |

| > 21 days | − 0.732 | 0.715 | 0.306 | 0.481 | 0.113 | 1.922 |

| Slatted flooring | ||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | − 1.795 | 0.548 | 0.001 | 0.166 | 0.052 | 0.456 |

| Farm location | ||||||

| Sassari | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Oristano | 1.553 | 0.678 | 0.022 | 4.724 | 1.335 | 19.761 |

| Use of disinfectants | ||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 1.923 | 0.653 | 0.003 | 6.841 | 2.048 | 27.400 |

| Use of halofuginone | ||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | − 1.294 | 0.741 | 0.080 | 0.274 | 0.054 | 1.064 |

| Milk replacer feeding | ||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 1.279 | 0.596 | 0.032 | 3.592 | 1.157 | 12.193 |

Molecular analysis

Amplicons of the SSU rRNA gene were obtained in 84.2% of the microscopic-positive samples (Table 3). PCR-RFLP analysis revealed the presence of two Cryptosporidium species in Sardinian calves, C. parvum and C. bovis. The former was the most frequent species, with a prevalence of 31.3%, and was present in both diarrhoeic and healthy animals. In fact, faeces from positive C. parvum calves were mostly solid (45.6%) and did not show mucus (86.0%) or blood (98.2%); only 17.5% of positive faecal samples were watery. Mixed logistic regression results indicated that the prevalence of C. parvum was significantly influenced by the faecal consistency (Table 1); thus, calves with watery diarrhoea presented a C. parvum-positive probability that was 3.59-fold higher (95% CI 1.18–10.94; p = 0.025) than those excreting solid faeces. The model showed that the presence of mucus or blood in faeces is not associated with C. parvum oocyst shedding. In addition, the mean C. parvum oocyst shedding intensity was 4.13 opf (SD = 6.29). The ANOVA test showed that oocyst counts were significantly higher (F = 12.178; p < 0.001) in watery samples (8.73 opf; SD = 6.13) than in those with a soft (3.23 opf; SD = 6.89) or solid consistency (1.45 opf; SD = 3.11). The post-hoc Tukey test showed that the differences were significant between liquid and solid faecal specimens (p < 0.001) and between liquid and soft samples (p = 0.001). Oocyst shedding was also higher in samples showing mucus (6.36 vs 2.89 opf) or blood (14.9 vs 3.18 opf), but these differences were not significant (p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Cryptosporidium species and C. parvum gp60 subtypes identified in pre-weaned calves from Sardinia

| Samples (n = 147) | Farms (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | 57/147 (38.8%) | 15/22 (68.2%) |

| Positive by SSU rRNA | 48/57 (84.2%) | 15/15 (100%) |

| C. parvum | 46/48 (95.8%) | 14/15 (93.3%) |

| C. bovis | 2/48 (4.2%) | 2/15 (13.3%) |

| Positive for C. parvum by gp60 | 38/46 (82.6%) | 12/14 (80.0%) |

| IIaA15G2R1 | 31/38 (81.6%) | 10/12 (83.3%) |

| IIaA16G3R1 | 2/38 (5.3%) | 2/12 (16.7%) |

| IId A20 | 2/38 (5.3%) | 1/12 (8.3%) |

| IIdA20G1b | 1/38 (2.6%) | 1/12 (8.3%) |

| Not readable | 2/38 (5.3%) | 2/12 (16.7%) |

C. bovis was only identified in two solid faecal samples from calves aged 7 and 16 days (1.4%). Both samples were then sequenced to confirm RFLP results, showing 100% homology with the reference C. bovis sequence MF074602 (Supplementary data). The intensity of C. bovis oocyst excretion was low, ranging between 0.05 and 1.10 opf.

A monospecific infection was identified in all animals and farms, except for one herd where both C. parvum and C. bovis were detected.

Cryptosporidium parvum subtyping analysis

Thirty-eight of 46 (82.6%) C. parvum isolates identified by PCR-RFLP of the SSU rRNA gene were positive to gp60 PCR. Sequencing gave 36 readable traces. SSU rRNA amplicons of the gp60-negative C. parvum isolates were sequenced to confirm the RFLP results. Four subtypes belonging to the families IIa and IId were identified, including the novel subtype IIdA20 (Table 3). IIaA15G2R1 was the most frequent and distributed subtype and was identified in 83.3% of C. parvum-positive farms. In contrast, the rest of the identified subtypes were occasional findings. It is worth noting that all IId subtypes were detected in calves from a single farm. All IIaA15G2R1 and IIdA20G1b isolates were 100% homologous to reference sequences MF142042, KY990913 and KU852712 (see Supplementary data). Both IIaA16G3R1 specimens were identical and exhibited a transversion (A instead T) in the non-repeating region when compared to the reference sequence HQ005741, resulting in a change from lysine to histidine. Likewise, the novel subtype IIdA20 exhibited a single nucleotide transition (C instead of T) downstream of the repeat region when compared to IIdA19G1 (GenBank accession number KY711525), resulting in a change from Val to Ala.

A single C. parvum subtype was identified in most farms, except for two herds where two gp60 alleles (IIaA15G2R1 + IIaA16G3R1 and IIdA20 and IIdA20G1b) were found.

Discussion

Our findings revealed that Cryptosporidium spp. are prevalent and widely distributed parasites in cattle farms from Sardinia. The individual percentage of infection is in line with previous investigations carried out in suckling calves from Sardinia, with values close to 33% (Scala and Garippa 1994; Scala et al. 2007). These results show that the percentage of Cryptosporidium-positive calves has remained high and constant in Sardinia during the last 20 years, suggesting that the control/preventive measures adopted have not been fully effective. In addition, the percentage of cryptosporidial infection was higher than those found in pre-weaned calves from other Italian regions, such as Central Italy (Duranti et al. 2009) or Sicily (Di Piazza et al. 2013), where prevalences did not exceed 25%.

The significant intra-herd prevalence values are a reflection of the high morbidity of this protozoan. It has been reported that some hygienic and management factors may favour dissemination of the protozoan in the farm, increasing the risk of infection (de Graaf et al. 1999; Castro-Hermida et al. 2002). Multivariate analysis of our data revealed several risk factors for calf positivity to Cryptosporidium spp. The risk of being positive was significantly higher in herds from Oristano, where the density of intensive cattle farms is far higher than in Sassari (Varcasia et al. 2006). The proximity of farms may favour oocyst dissemination and indirect transmission by fomites such as clothes or footwear (particularly by farmers or veterinary surgeons), shared farm tools or even insects (Graczyk et al. 1999; Bihn and Gravani 2006; Bouzid et al. 2013).

Although cryptosporidial infection is considered especially common in animals living in overcrowded and oocyst-contaminated environments (Mohammed et al. 1999; Castro-Hermida et al. 2002), general calf cleanliness and stalling of calves were not identified as decisive factors. Our results show that the risk of being positive was significantly higher in herds using straw on earth or cement flooring. Although deep and regular straw bedding seems to keep calves clean from faeces (Wells and Thompson 2014), poor or infrequent bedding maintenance was very common in the cattle farms studied, leading to an increase in the faecal contamination of stalls and thus the risk of infection. In contrast, Muhid et al. (2011) found that calves kept in pens with slatted floors had an increased risk compared with those in pens with cement floors. Surprisingly, the application of disinfectants was significantly associated with higher prevalence of the protozoan, suggesting the use of incorrect cleaning and disinfection routine practices. Several investigations have proved that thick-walled Cryptosporidium oocysts are highly resistant to adverse external conditions, including those disinfectants most commonly used in animal husbandry (Fayer 2008). In our study, 36.1% of farmers stated that they disinfected calf pens using ammonia, iodine or lime, but only ammonia has shown good efficacy against the protozoan (Fayer 2008). Our results also suggest that farmers used concentrations of disinfectants insufficient to reduce oocyst infectivity. Moreover, their pre-disinfection cleaning methods failed to remove organic soiling, consequently reducing disinfectant efficacy and increasing the likelihood of oocyst survival in the environment (Fotheringham 1995). Thus, most farmers using disinfectants did not achieve effective removal or inactivation of oocysts, but a dispersion of oocysts favouring calf infection.

A significant preventive effect of halofuginone treatment was also identified in the risk factor analysis. These results are consistent with several investigations that found halofuginone is an effective drug for the prophylactic treatment of Cryptosporidium infections, causing a reduction in oocyst shedding and diarrhoeal disease (Trotz-Williams et al. 2011; Delafosse et al. 2015). The association of Cryptosporidium positivity and use of milk replacers might be related to oocyst contamination due to the milk replacer being prepared or stored in unhygienic conditions (McGuirk 2003). In addition, since poor nutrition is also related to immunosuppression, using poor-quality milk replacers could negatively influence leukocyte responses and resistance to different enteropathogens (Ballou et al. 2015; Hammon et al. 2018), thereby favouring cryptosporidial infection.

In summary, effective control and preventive measures including correct cleaning and disinfection routine practices, administration of halofuginone and good quality milk replacers or the use of slatted flooring should be adopted, particularly in farms from Central Sardinia, to reduce the protozoan’s presence in farms and consequently lower the cryptosporidiosis outbreak risk. All these findings could be very useful to Sardinian cattle farmers since they strongly suggest that suitable control measures would reduce both the impact and risk of the disease on animal health.

Only two Cryptosporidium species were identified: C. parvum was clearly predominant, whereas C. bovis was found only occasionally. These results endorse previous molecular studies carried out in cattle from Europe and North America which found that C. parvum is the main Cryptosporidium species affecting both diarrhoeic and healthy suckling calves (Santín et al. 2004, 2008; Trotz-Williams et al. 2006; Quílez et al. 2008; Díaz et al. 2010; Castro-Hermida et al. 2011; Imre and Dărăbus 2011; Duranti et al. 2009).

Shedding of C. parvum oocysts was significantly associated with watery diarrhoea, mainly in calves younger than 2 weeks, which presented a higher probability of being positive than other animals; these results are in line with previous studies (Kváč et al. 2006; Duranti et al. 2009; Garro et al. 2016). C. parvum is broadly recognised as the most pathogenic species for cattle, since it is responsible for the appearance of important neonatal diarrhoea outbreaks in farms (Santín et al. 2004; Fayer et al. 2006; Santín and Trout 2008; Quílez et al. 2008; Díaz et al. 2010; Imre and Dărăbus 2011), although in some studies, it has also been identified as the major or the only species in healthy cattle (Santín et al. 2004; Castro-Hermida et al. 2011; Trotz-Williams et al. 2006; Fayer et al. 2007; Duranti et al. 2009).

The presence of mucus or blood in faeces was not related to the presence of C. parvum due to its superficial location in the intestinal epithelium (Aurich et al. 1990; Castro-Hermida et al. 2002). Nevertheless, some bloody and mucous faecal samples tested positive to the protozoan, suggesting co-infection with other bacterial, viral or parasitic enteropathogens such as rotavirus, coronavirus, Escherichia coli or Giardia duodenalis (Castro-Hermida et al. 2002; García-Meniño et al. 2015). Since C. parvum is considered the most important Cryptosporidium zoonotic species (Xiao 2010), the high occurrence of the parasite in Sardinian cattle farms may have significant public health implications.

C. bovis was of little significance in pre-weaned calves since it was only identified in two asymptomatic calves aged 7–13 days. Our results endorse most Cryptosporidium investigations in cattle reporting C. bovis as a host-specific and low-pathogenic species particularly common in post-weaned calves and heifers (Santín et al. 2008; Šlapeta et al. 2013). In contrast, C. bovis has also been reported as the most common Cryptosporidium species in pre-weaned calves from the five continents (Ayinmode et al. 2010; Silverlås et al. 2010; Ng et al. 2011; Budu-Amoako et al. 2012; Abeywardena et al. 2014), although its presence is especially important in suckling calves in China (Wang et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2015; Ma et al. 2015; Fan et al. 2017). The sporadic detection of this species in the present study may be a consequence of the low-intensity oocyst excretion values observed, usually below the detection limit of diagnostic tests. In addition, considering the high prevalence and oocyst shedding of C. parvum in pre-weaned calves, the exponential amplification of PCR methods could mask the presence of C. bovis in animals showing mixed infections. In addition, C. bovis is considered a non-zoonotic species, although it has been detected sporadically in humans from Australia (Ng et al. 2012), Egypt (Helmy et al. 2013) and India (Khan et al. 2010).

When the genetic diversity within C. parvum was analysed, four subtypes belonging to the subtype families IIa and IId were found. Our results are consistent with previous investigations reporting these two subtype families as the most common in cattle worldwide, particularly IIa, although other subtype families, such as IIj and IIl, have also been sporadically found (Xiao 2010). The low genetic diversity observed may be due to the low number of isolates subtyped or to a genetic isolation because of insularity. Both IIa subtypes identified, IIaA15G2R1 and IIaA16G3R1, have zoonotic potential; thus, the former is considered the most common C. parvum subtype in humans (Trotz-Williams et al. 2006; Xiao and Ryan 2008; Xiao 2010). C. parvum subtype family IId has been involved in a significant number of human cryptosporidiosis cases (Cui et al. 2014; Ibrahim et al. 2016). The two IId subtypes identified in the present study are not common; in fact, IIdA20 is a novel C. parvum subtype in cattle. They both originated from the northwesternmost farm studied, geographically distant from the other farms. Both subtypes were detected in asymptomatic calves, and the intensity of oocyst excretion was low, ranging from 0.1 to 4.6 opf. Finally, the finding of a single C. parvum gp60 subtype in most positive farms indicates that molecular subtyping techniques are useful tools for identifying and tracking cryptosporidiosis outbreaks in humans and animals.

In conclusion, our results reveal that a significant percentage of healthy and diarrhoeic suckling calves in Sardinia are carriers of zoonotic subtypes of C. parvum, representing a risk for the appearance of cryptosporidiosis outbreaks not only in animals but also in humans.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 18 kb)

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Project AGL2016-76034-P (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spain) and by a grant for Consolidating and Structuring Competitive Research Groups (GRC2015/003, Xunta de Galicia). The authors would like to thank Mr. F. Salis, Technician, Parasitology Laboratory, University of Sassari for technical assistance during the study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Organism in charge for the Animal Welfare and Experimentation of the University of Sassari (approval number 50657).

References

- Abeywardena H, Jex AR, Koehler AV, Rajapakse RP, Udayawarna K, Haydon SR, Stevens MA, Gasser RB. First molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from bovines (Bos taurus and Bubalus bubalis) in Sri Lanka: unexpected absence of C. parvum from pre-weaned calves. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:75. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves M, Xiao L, Sulaiman I, Lal AA, Matos O, Antunes F. Subgenotype analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from humans, cattle, and zoo ruminants in Portugal. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2744–2747. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2744-2747.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurich JE, Dobrinski I, Grunert E. Intestinal cryptosporidiosis in calves on a dairy farm. Vet Rec. 1990;127:380–381. doi: 10.1136/vr.127.15.380.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayinmode AB, Olakunle FB, Xiao L. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in native calves in Nigeria. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:1019–1021. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1972-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballou MA, Hanson DL, Cobb CJ, Obeidat BS, Sellers MD, Pepper-Yowell AR, Carroll JA, Earleywine TJ, Lawhon SD. Plane of nutrition influences the performance, innate leukocyte responses, and resistance to an oral Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium challenge in Jersey calves. J Dairy Sci. 2015;98:1972–1982. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2014) lme4: linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4 R Package Version 1. 1–7, URL: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4.

- Bihn E, Gravani R. Role of good agricultural practices in fruit and vegetable safety microbiology of fresh produce. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzid M, Hunter PR, Chalmers RM, Tyler KM. Cryptosporidium pathogenicity and virulence. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:115–134. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00076-12.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budu-Amoako E, Greenwood SJ, Dixon BR, Barkema HW, McClure JT. Giardia and Cryptosporidium on dairy farms and the role these farms may play in contaminating water sources in Prince Edward Island, Canada. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26:668–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2012.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Hermida JA, González-Losada YA, Ares-Mazas E. Prevalence of and risk factors involved in the spread of neonatal bovine cryptosporidiosis in Galicia (NW Spain) Vet Parasitol. 2002;106:1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00036-5.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Hermida JA, García-Presedo I, Almeida A, González-Warleta M, Correia Da Costa JM, Mezo M. Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis in two areas of Galicia (NW Spain) Sci Tot Environ. 2011;409:2451–2459. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Wang R, Huang J, Wang H, Zhao J, Luo N, Li J, Zhang Z, Zhang L. Cryptosporidiosis caused by Cryptosporidium parvum subtype IIdA15G1 at a dairy farm in North-western China. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:529. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0529-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf DC, Vanopdenbosch E, Ortega-Mora LM, Abbassi H, Peeters JE. A review of the importance of cryptosporidiosis in farm animals. Int J Parasitol. 1999;29:1269–1287. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00076-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delafosse A, Chartier C, Dupuy MC, Dumoulin M, Pors I, Paraud C. Cryptosporidium parvum infection and associated risk factors in dairy calves in western France. Prev Vet Med. 2015;118:406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz P, Quílez J, Chalmers RM, Panadero R, López CM, Sánchez-Acedo C, Morrondo P, Díez-Baños P. Genotype and subtype analysis of Cryptosporidium isolates from calves and lambs in Galicia (NW Spain) Parasitology. 2010;137:1187–1193. doi: 10.1017/S0031182010000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Piazza F, Di Benedetto MA, Maida CM, Glorioso S, Adamo G, Mazzola T, Firenze A. A study on occupational exposure of Sicilian farmers to Giardia and Cryptosporidium. J Prev Med Hyg. 2013;54:212–217. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranti A, Cacciò SM, Pozio E, Di Egidio A, De Curtis M, Battisti A, Scaramozzino P. Risk factors associated with Cryptosporidium parvum infection in cattle. Zoonoses Public Health. 2009;56:176–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwin K, Chalmers RM, Roberts R, Guy EC, Casemore DP. Modification of a rapid method for the identification of gene-specific polymorphisms in Cryptosporidium parvum and its application to clinical and epidemiological investigations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5581–5584. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5581-5584.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Wang T, Koehler AV, Hu M, Gasser RB. Molecular investigation of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in pre- and post-weaned calves in Hubei Province, China. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:519. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2463-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer Ronald. Cryptosporidium and Cryptosporidiosis, Second Edition. 2007. General Biology; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R, Morgan U, Upton SJ. Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium: transmission, detection and identification. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:1305–1322. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R, Santin M, Trout JM, Greiner E. Prevalence of species and genotypes of Cryptosporidium found in 1-2-year-old dairy cattle in the eastern United States. Vet Parasitol. 2006;135:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R, Santin M, Trout JM. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium species and genotypes in mature dairy cattle on farms in eastern United States compared with younger cattle from the same locations. Vet Parasitol. 2007;145:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham VJC. Disinfection of livestock production premises. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epiz. 1995;14:191–205. doi: 10.20506/rst.14.1.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Meniño I, Díaz P, Gómez V, Prieto A, Fernández G, Díez-Baños P, Morrondo P, Mora A. Estudio de la prevalencia de enteropatógenos implicados en las diarreas del ternero en Galicia. Boletín de ANEMBE. 2015;108:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Garro CJ, Morici GE, Utgés ME, Tomazi ML, Schnittger DL. Prevalence and risk factors for shedding of Cryptosporidium spp. oocysts in dairy calves of Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2016;1:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graczyk TK, Fayer R, Cranfield MR, Mhangami-Ruwende B, Knight R, Trout JM, Bixler H. Filth flies are transport hosts of Cryptosporidium parvum. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:726–727. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grana L, Lalle M, Habluetzel A, Silvestri S, Traldi G, Tonanti D, Pozio E, Caccio SM. Distribution of zoonotic and animal specific genotypes of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in calves of cattle farms in the Marche region. Parassitologia. 2006;48:208. [Google Scholar]

- Hammon HM, Frieten D, Gerbert C, Koch C, Dusel G, Weikard R, Kühn C. Different milk diets have substantial effects on the jejunal mucosal immune system of pre-weaning calves, as demonstrated by whole transcriptome sequencing. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1693):1693. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19954-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmy YA, Krücken J, Nöckler K, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Zessin KH. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium in livestock animals and humans in the Ismailia province of Egypt. Vet Parasitol. 2013;193:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MA, Abdel-Ghan AE, Abdel-Latef GK, Abdel-Aziz SA, Aboelhadid SM. Epidemiology and public health significance of Cryptosporidium isolated from cattle, buffaloes, and humans in Egypt. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2439–2448. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-4996-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imre K, Dărăbus G. Distribution of Cryptosporidium species, genotypes and C. parvum subtypes in cattle in European countries. Sci Parasitol. 2011;12:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT, Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (2017) Annual Report on Bovine consistence in Sardinia. http://agri.istat.it/sag_is_pdwout/jsp/dawinci.jsp?q=plB010000030000103200&an=2017&ig=1&ct=201&id=8A|10A|71A|47A|9A. Accessed 08 April 2018

- Jiang J, Alderisio KA, Xiao L. Distribution of Cryptosporidium genotypes in storm event water samples from three watersheds in New York. App Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:4446–4454. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4446-4454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM, Debnath C, Pramanik AK, Xiao L, Nozaki T, Ganguly S. Molecular characterization and assessment of zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium from dairy cattle in West Bengal, India. Vet Parasitol. 2010;171:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kváč M, Kouba M, Vitovec J. Age-related and housing-dependence of Cryptosporidium infection of calves from dairy and beef herds in South Bohemia, Czech Republic. Vet Parasitol. 2006;137:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Li P, Zhao X, Xu H, Wu W, Wang Y, Guo Y, Wang L, Feng Y, Xiao L. Occurrence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in dairy cattle, beef cattle and water buffaloes in China. Vet Parasitol. 2015;207:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuirk SM (2003). Solving calf morbidity and mortality problems. 36th Annual Conference of the American Association of Bovine Practitioners, September 15–17, 2003- Columbus, OH.

- Merildi V, Mancianti F, Lamioni H, Passantino A, Papini R (2009) Preliminary report on prevalence and genotyping of Cryptosporidium spp. in cattle from Tuscany (Central Italy). III-rd International Giardia and Cryptosporidium Conference, Orvieto, Italy, Abstract Book 84.

- Mohammed HO, Wade SE, Schaaf S. Risk factors associated with Cryptosporidium parvum infection in dairy cattle in southeastern New York State. Vet Parasitol. 1999;83:1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00032-1.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhid A, Robertson I, Ng J, Ryan U. Prevalence and management factors contributing to Cryptosporidium sp. infection in pre-weaned and post-weaned calves in Johor, Malaysia. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127:534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naciri M, Lefay MP, Mancassola R, Poirier P, Chermette R. Role of Cryptosporidium parvum as a pathogen in neonatal diarrhoea complex in suckling and dairy calves in France. Vet Parasitol. 1999;85:245–257. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng J, Yang R, McCarthy S, Gordon C, Hijjawi N, Ryan U. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in pre-weaned calves in Western Australia and New South Wales. Vet Parasitol. 2011;176:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng JS, Eastwood K, Walker B, Durrheim DN, Massey PD, Porigneaux P, Kemp R, McKinnon B, Laurie K, Miller D, Bramley E, Ryan U. Evidence of Cryptosporidium transmission between cattle and humans in northern New South Wales. Exp Parasitol. 2012;130:437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson ME, O’Handley RM, Ralston BJ, McAllister TA, Thompson RC. Update on Cryptosporidium and Giardia infections in cattle. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papini R, Bonelli F, Montagnani M, Sgorbini M (2018) Evaluation of three commercial rapid kits to detect Cryptosporidium parvum in diarrhoeic calf stool. Ital J Anim Sc:1–6. 10.1080/1828051X.2018.1452055

- Quílez J, Torres E, Chalmers RM, Robinson G, del Cacho E, Sánchez-Acedo C. Cryptosporidium species and subtype analysis from dairy calves in Spain. Parasitology. 2008;135:1613–1620. doi: 10.1017/S0031182008005088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razakandrainibe R, Diawara EHI, Costa D, Le Goff L, Lemeteil D, Ballet JJ, Gargala G, Favennec L. Common occurrence of Cryptosporidium hominis in asymptomatic and symptomatic calves in France. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford SE, Josephson GK. Bovine cryptosporidiosis: clinical and pathological findings in forty-two scouring neonatal calves. Can Vet J. 1982;23:343–347. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santín M, Trout JM (2008) Livestock. In: Fayer R, Xiao L (eds.) Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis, 2nd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 437–449

- Santín M, Trout JM, Xiao L, Zhou L, Greiner E, Fayer R. Prevalence and age-related variation of Cryptosporidium species and genotypes in dairy calves. Vet Parasitol. 2004;122:103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santín M, Trout JM, Fayer R. A longitudinal study of cryptosporidiosis in dairy cattle from birth to 2 years of age. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scala A, Garippa G. Rilievi epidemiologici sulla criptosporidiosi bovina in Sardegna. Atti Sisvet. 1994;48:1279–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Scala A, Basciu M, Tanda B, Arias M, Cortinas J, Diaz P, Sanchez-Andrade R, Paz-Silva A (2007) Prevalence of bovine cryptosporidiosis in Sardinia (Italy). 21st international conference of the World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology: 484

- Silverlås C, Näslund K, Björkman C, Mattsson JG. Molecular characterisation of Cryptosporidium isolates from Swedish dairy cattle in relation to age, diarrhoea and region. Vet Parasitol. 2010;169:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sischo WM, Atwill ER, Lanyon LE, George J. Cryptosporidia on dairy farms and the role these farms may have in contaminating surface water supplies in the Northeastern United States. Prev Vet Med. 2000;43:253–267. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(99)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šlapeta J. Cryptosporidiosis and Cryptosporidium species in animals and humans: a thirty colour rainbow? Int J Parasitol. 2013;43:957–970. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2013.07.005.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman IM, Hira PR, Zhou L, Al-Ali FM, Al-Shelahi FA, Shweiki HM, Iqbal J, Khalid N, Xiao L. Unique endemicity of cryptosporidiosis in children in Kuwait. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2805–2809. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2805-2809.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotz-Williams LA, Martin DS, Gatei W, Cama V, Peregrine AS, Martin SW. Genotype and subtype analyses of Cryptosporidium isolates from dairy calves and humans in Ontario. Parasitol Res. 2006;99:346–352. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotz-Williams LA, Jarvie BD, Peregrine AS, Duffield TF, Leslie KE. Efficacy of halofuginone lactate in the prevention of cryptosporidiosis in dairy calves. Vet Rec. 2011;168:509. doi: 10.1136/vr.d1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varcasia A, Capelli G, Ruiu A, Ladu M, Scala A, Bjorkman C. Prevalence of Neospora caninum infection in Sardinian dairy farms (Italy) detected by iscom ELISA on tank bulk milk. Parasitol Res. 2006;98:264–267. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-0044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Wang H, Sun Y, Zhang L, Jian F, Qi M, Ning C, Xiao L. Characteristics of Cryptosporidium transmission in preweaned dairy cattle in Henan, China. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1077–1182. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02194-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells B, Thompson S (2014). Cryptosporidiosis in cattle. The Moredun Foundation News Sheet 6.

- Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Ryan UM (2008) Molecular epidemiology. In: Fayer R, Xiao L (eds). Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. 2nd edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 119–172.

- Zahedi A, Monis P, Aucote S, King B, Paparini A, Jian F, Yang R, Oskam C, Ball A, Robertson I, Ryan U. Zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in animals inhabiting Sydney water catchments. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0168169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XX, Tan QD, Zhou DH, Ni XT, Liu GX, Yang YC, Zhu XQ. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in dairy cattle, northwest China. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:2781–2787. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 18 kb)