Abstract

Receptor recognition and binding is the first step in the viral cycle. It has been established that Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV) interacts with sialylated molecules such as gangliosides and glycoproteins at the cell surface. Nevertheless, the specific receptor(s) that mediate virus entry are not well known. We have analysed the role of the sialic acid linkage in the early steps of the viral infection cycle. Pretreatment of ELL-0 cells with both α2,3 and α2,6 specific sialidases led to the inhibition of NDV binding, fusion and infectivity, which were restored after α2,3(N)- and α2,6(N)-sialyltransferase incubation. Moreover, α2,6(N)-sialyltransferases also restored NDV activities in α2-6-linked sialic acid deficient cells. Competition with α2-6 sialic acid-binding lectins led to a reduction in the three NDV activities (binding, fusion and infectivity) suggesting a role for α2-6- linked sialic acid in NDV entry. We conclude that both α2-3- and α2-6- linked sialic acid containing glycoconjugates may be used for NDV infection. NDV was able to efficiently bind, fuse and infect the ganglioside-deficient cell line GM95 to a similar extent to that of its parental MEB4, suggesting that gangliosides are not essential for NDV binding, fusion and infectivity. Nevertheless, the fact that the interaction of NDV with cells deficient in N-glycoprotein expression such as Lec1 was less efficient prompted us to conclude that NDV requires N-linked glycoproteins for efficient attachment and entry into the host cell.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10719-012-9431-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Virus sialidase, Sialic acid, Viral receptor, NDV, Paramyxovirus

Introduction

The initial step of virus entry into the host cell consists of receptor recognition and binding. For this, most viruses have a receptor binding protein at their surface. Many paramyxoviruses, as well as some orthomyxoviruses, polyomaviruses, rotaviruses, coronavirus, and adenoviruses, use sialic acid containing molecules as receptors at the cell surface [1–7]. Sialic acid residues are found at the outermost ends of gangliosides (glycosphingolipids) and N- and O-glycoproteins bound to Gal residues, with α2-3- or α2-6-linkages. Additionally, sialic acids may be bound to other sialic acid in an α2-8-linkage [8]. The specific linkage of sialic acid residue to glycoconjugates is believed to be one of the major determinants of viral tropism in the above mentioned group of viruses. Different influenza strains vary in their specificities as regards sialic acid linkages (α2-3 or α2-6) and the type of sialic acid residue (NeuAc, NeuGc, or 9-O-Ac-NeuAc) (references in [9]). Influenza A viruses bind to sialic acid-containing molecules with specificities that vary according to the host species [10]; influenza human viruses mainly recognize α2-6-linked sialic acids whereas avian influenza viruses prefer α2-3- [10, 11]. A conversion from α2-3 to α2-6 sialic acid recognition is thought to be one of the changes that must occur before avian influenza viruses can replicate efficiently in humans and acquire the potential to cause a pandemic. In addition, it has been proposed that glycan topology, rather than sialic acid linkages, may be critical in interactions of influenza A with target cells [2, 12]. To add further complexity, influenza viruses are able to infect cells in the absence of any surface sialic acid [13] or independently of cell surface sialic acid content [14].

Among the paramyxoviruses, ganglioside-bearing sialic acids attached in α2-3-linkage have been described as the main receptors for the type-1 murine paramyxovirus virus or Sendai virus [15, 16]. Additionally, the binding of Sendai virus to gangliosides with both terminal α2-3 and α2-6 sialic acid- linkages has been reported [17]. Using a solid-phase binding assay, Suzuki et al. [18] showed that hPIV1 preferably binds to α2-3-linked sialic acids, whereas hPIV3 strongly bound α2-3- and α2-6-linked sialic acids.

Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV), a prototype of paramyxoviruses, is an avian enveloped RNA-negative strand virus that causes respiratory disease in domestic fowl, leading to huge economic losses in the poultry industry. The envelope of NDV contains two associated glycoproteins that mediate viral entry: the haemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN) and fusion (F) proteins. HN is the receptor-binding protein that recognizes and binds to sialoglycoconjugates at the cell surface [1] and also has sialidase activity in separate sites [19]. Based on crystallographic studies of the HN of NDV, two sialic acid-binding sites have been described [20, 21]. Site I would support both receptor-destroying and receptor-binding activities, while site II only receptor-binding activity. It remains unknown whether both sialic acid-binding sites might interact with the same cell surface molecule(s). Site I of hPIV1 binds α2-6-linked sialic acids, whereas site II binds both α2-3- and α2-6-linked sialic acids [22]. A secondary sialic acid-binding site that bind α2,3 sialyllactose in neuraminidase (=sialidase) from avian, human and swine influenza viruses has been described [23].

Although it has long been known that NDV requires sialylated glycoconjugates for binding to cells, the exact nature of the receptor and the specific linkage for the sialic acid have not been well defined. In previous work, Suzuki et al. [24] determined the specificity of NDV for gangliosides with terminal α2-3-linked sialic acids but not terminal α2-6, although only a reduced number of gangliosides were assayed. We have previously reported that in vitro assays NDV binds/recognizes different gangliosides with sialic acids, both terminal and internal [25]; moreover N-glycoproteins, but not O-glycoproteins, were required for optimal viral entry [25]. Additionally, we have shown that the binding of NDV to free gangliosides or to free sialic acids triggers a conformational change in HN protein that exposes hydrophobic sites [26].

The present study focuses on NDV interactions with the sialoglycoconjugates present at the outer plasma membrane of different cell lines, providing new information about NDV receptors. We analyzed the sialyl linkage specificity of NDV using different sialidases and lectins that recognize α2-3 or α2-6 sialyl linkages differently. Sialidase and lectin treatment revealed that NDV uses both α2-3- and α2-6-sialylated glycans. NDV interacts efficiently with the ganglioside-deficient cell line GM95, meaning that other sialylated molecules, i.e. N-linked glycoproteins, may function as effective receptors in the absence of gangliosides. Nevertheless, the interaction of NDV with the Lec1 cell line deficient in N-glycosylation was less efficient as compared with its parental CHO. After comparing the data concerning NDV interactions with both mutant cell lines, GM95 and Lec1, we concluded that glycoproteins seem to be more critical than gangliosides for NDV interactions with the target cell. The data presented here regarding NDV receptor specificity would be relevant for understanding viral tropism and for developing new antiviral strategies targeting viral receptors.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and virus

East Lansing Line (ELL-0) avian fibroblasts and 293T cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC); MEB4 and GM95 were obtained from Riken BRC Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan); ELL-0, MEB4 and GM95 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM); Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) and mutant Lec1 were also purchased from ATCC and maintained in DMEM:F12 and AlphaMEM media respectively. All media were supplemented with L-GlutaMax (580 mg l−1, Invitrogen), penicillin-streptomycin (100 U ml−1–100 μg ml−1) and 10 % heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum (complete medium). The lentogenic “Clone 30” strain of NDV was obtained from Intervet Laboratories (Salamanca, Spain). The virus was grown and purified mainly as described previously [27].

Reagents and antibodies

FITC-Maackia amurensis lectin (FITC-MALI), CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-NeuAc), GM1, GM3, GT1b, GD1a and AsialoGM1 gangliosides, Arthrobacter ureafaciens-, Clostridium perfringens- and Vibrio cholerae- sialidases were from Sigma-Aldrich; α2,3(N)-, α2,6(N)- and α2,3(O)-sialyltransferases (STs) were from Calbiochem; octadecyl rhodamine B chloride (R18), Hoechst 33258, and Alexafluor 488 donkey anti-mouse antibody were from Molecular Probes. FITC-SNA and MALI lectins were from Vector Laboratories; monoclonal anti-F (2A6) antibody was generous gift from Dr. Adolfo García-Sastre (Emerging Pathogens Institute, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, USA); monoclonal anti-HN 14f and 1b antibodies were kindly provided by Dr. Ronald M. Iorio (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, USA).

Virus titration

Virus titres were calculated in plaque-formation assays in ELL-0 cells, as described [28]. Plaque numbers were counted under a light microscope and NDV infectivity was expressed as plaque forming units (pfu) ml−1.

Virus-binding assays

Virus binding was assayed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Plated cells were washed three times with ice-cold OptiMEM, and incubated with NDV at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 1 or 5 for 1 h at 4 °C. Then, the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS to remove unbound virus and were collected by scraping or by incubation with 1 ml EDTA (520 μM) at 37 °C for performing FACS analyses mainly as previously described [29] probing with both anti-F and anti-HN mAbs. Data were analyzed with the WinMDI 2.9 software.

NDV-cell fusion assays

Purified NDV was labelled with the fluorescent probe R18 essentially as described previously [30]. Cells plated in 35-mm plates treated or untreated with lectins, sialidases or sialyltranferases were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C on ice with 3 μg of R18-NDV per plate. Then, cells were washed four times with cold PBS and incubated in complete medium containing Hoechst 33258 (10 μg ml−1) for 1 h at 37 °C. They were fixed with 2 % formaldehyde in PBS and the transfer of the rhodamine probe to cells was observed under an Olympus IX51 inverted fluorescence microscope. The percentage of fusion was calculated as the number of positive red-stained cells in 10 random fields with respect to the total number of cells in these areas of the well.

NDV infectivity assays

Monolayers of cells were infected for 1 h at room temperature with different dilutions of a recombinant NDV derived from the Hitchner B1lentogenic strain (rNDV-F3aa-mRFP [31]), that expresses a monomeric red-fluorescent protein [32], kindly provided by Dr. Adolfo García-Sastre. After 24 h at 37 °C, the cells were observed under an Olympus IX51 inverted fluorescence microscope with a 10 x objective. The percentage of infectivity was calculated as the number of red-fluorescent cells out of the total number of cells in six random fields.

Sialidase treatment of cells

Cell monolayers at 80 % confluence in 24-well plates were washed with OptiMEM and incubated in the presence of sialidases (25 mU/ml for V.cholerae- and A.ureafaciens-sialidases and 50 mU/ml for C.perfringens- sialidase) for 1 h at 37 °C. For V.cholerae- sialidase incubations, OptiMEM was adjusted to pH 5.7 and supplemented with 4 mM CaCl2. After sialidase treatments, cells were washed once with OptiMEM and analysed in binding, fusion and infectivity assays.

Sialyltransferase treatment of cells

Cell monolayers in 24-well plates at 80 % confluence were washed once with OptiMEM and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in the presence of V.cholerae- sialidase at 25 mU/ml. After washing once with OptiMEM, the CMP-NeuAc substrate and α2,3(N)-, α2,6(N)- and α2,3(O)- STs were added to sialidase-treated cells. For fusion experiments, the concentration of STs was 50 mU/ml except for experiments with α2,6(N)-ST in MEB4 and Lec1 in which the enzyme was added at 25 mU/ml; for infectivity experiments the concentration of STs was 25 mU/ml. All samples (untreated cells, sialidase-treated cells and sialidase-ST-treated cells) were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Then, cells were washed once in OptiMEM and used in fusion or infectivity assays.

Lectin inhibition and staining assays

For lectin inhibition experiments, cell monolayers at 80 % confluence in 24-well plates were washed once with OptiMEM and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with increasing concentrations of SNA, MALI or lentil lectins. Cells were washed once with OptiMEM and analysed in binding, fusion or infectivity assays.

Lectin staining of cells was performed by incubation of the cells with FITC-labelled lectins, FITC-MALI, FITC-SNA, and FITC-Arachis hypogaea lectin, which recognizes Gal residues. For fluorescence microscopy assays, cells growing on 24-well plates were chilled to 4 °C, and then lectin (10 μg/ml for A.hypogaea lectin or 20 μg/ml for MALI and SNA lectins) was added in OptiMEM. Cultures were incubated at 4 °C for 30 min and washed once with OptiMEM. Lectin binding to cells was observed under an Olympus IX51 inverted fluorescence microscope with a 10 x objective or by FACS as above.

Ganglioside purification from MEB4 and GM95 cells

Total gangliosides were extracted from MEB4 y GM95 cells by total lipid extraction, diisopropylether (DIPE)/1-butanol/aqueous phase partition and Sephadex G-50 gel filtration, according to [33, 34] mainly as previously described [25].

TLC

Gangliosides from MEB4 and GM95 cells and individual gangliosides were separated by HPTLC on plastic silica gel 60 plates (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) using chloroform/methanol/water (50:45:10, v/v/v) containing 0.02 % CaCl2 as the mobile phase. Chemical staining to visualize sialic acid- containing glycoconjugates (gangliosides) was achieved by resorcinol (resorcinol-hydrochloric acid) staining [35], which stains sialic acid a bluish purple colour.

Statistics

The two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was used to determine statistical significance between two groups. Probability values of p < 0.001 were considered extremely statistically significant: p < 0.01 extremely significant and p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with the QuickCalcs program from GraphPad software.

Results and discussion

To obtain further information about the nature of the NDV receptor, we analysed the interaction of NDV with five target cell lines that differ in their surface glycoconjugate expression: ELL-0, a chicken fibroblast from the natural host of the virus; GM95, a glycosphingolipid-deficient cell line due to the lack of the enzyme glycosylceramide synthetase and its parental cell line MEB4 [36]; CHO and their mutant Lec1, a N-glycoprotein-deficient cell line caused by a mutation in N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase I gene [37, 38]. Lec1 is deficient in complex N-linked glycosylation but is not deficient in glycosphingolipids or O-glycoproteins [39].

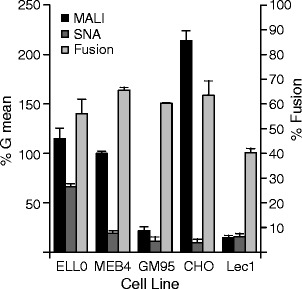

The relative levels of α2-3- and α2-6-linked sialic acid expression at the cell surface were analyzed by fluorescent lectin staining in a FACS assay, as detailed in Methods. Cells were probed with FITC-MALI, which binds α2-3-linked sialic acids [40], or FITC-SNA, which recognizes α2-6-linked sialic acids [41]. Data summarized in Fig. 1 (left axis of ordinates) and Supplementary Fig. S1 showed high level of α2-3-linked sialic acid residues present in cell membrane glycoconjugates in three of the cell lines (ELL-0, MEB4 and CHO), whereas GM95 and Lec1 cells showed low levels of such linkages; a significant amount of α2-6 linked sialic acid was only detected in ELL-0 cells. In spite of these differences, NDV fused efficiently with the five cell lines (Fig. 1, right axis of ordinates). Accordingly, it may be concluded that there was no correlation between the sialic acid level and the level of NDV fusion.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of the relative levels of α2-3 and α2-6-linked sialic acids on the cell surface and the degree of NDV fusion. Left ordinate axis: the relative surface levels of α2-3 and α2-6-linked sialic acids was measured by FACS analysis using FITC-MALI (specific for α2-3 sialic acids) or FITC-SNA (specific for α2-6 sialic acids). Data represent geometric means±standard deviations of three independent experiments. Right ordinates axis: Degree of NDV fusion. R18-labeled NDV (3 μg) was bound to cells for 1 h at 4 °C, after which they were allowed to fuse for 1 h at 37 °C. Fusion was assessed by transfer of the R18 red dye to the cell membrane and was quantified as detailed in Methods. Data are means±standard deviations of three independent experiments

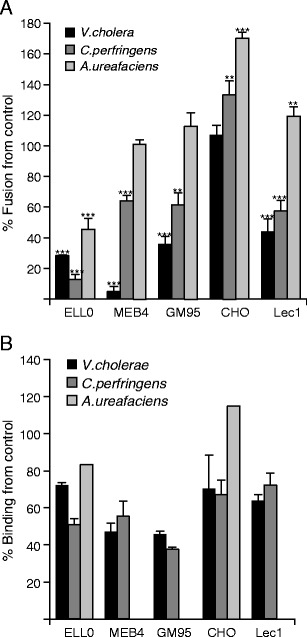

Enzymatic removal of cell surface sialic acid residues was achieved by treatment with sialidases from V.cholera and C.perfringens, both of which preferably cleave α2-3-linked sialic acid from glycolipids and glycoproteins (manufacturer’s specifications); and sialidase from A.ureafaciens, which has a preference for cleaving α2-6-linked sialic acids [42]. The efficiency of sialic acid removal after enzymatic treatment was tested by fluorescent lectin staining (Supplementary Fig. S2). Surprisingly, we detected an increase in the FITC-MALI staining of CHO cells after C.perfringens sialidase treatment (Supplementary Fig. S2B), suggesting that the removal of several sialic acids might unmask some sialoglycoconjugates at the cell surface recognized by this lectin. We analyzed the effect of the depletion of receptors caused by sialidases on NDV binding, fusion and infectivity in enzyme-treated cells. The fusion activity of NDV with enzyme-treated cells was analysed by a fluorescent assay, as detailed in Methods. As expected, the removal of α2-3-linked sialic acid afforded a significant reduction in viral fusion in four of the five cell lines (Fig. 2a); pretreatment of cells with the α2,6 sialidase afforded a 50 % NDV fusion inhibition only in ELL-0 cells. Similarly, the fusion of hPIV3, another paramyxovirus, was also inhibited after both α2,3 and α2,6 sialidase treatments [43]. Additionally, NDV efficiently fuses and infects 293 T cells (data not shown) that preferably have α2-6-linked sialic acids at their plasma membrane [44] . This result strongly suggests that, if present at the cell surface, NDV may use α2-6-linked sialic acids as receptors. C.perfringens sialidase treatment increased 1.3 fold the efficiency of NDV fusion with CHO cells (Fig. 2a), in accordance with the observed enhancement of MALI lectin staining in C.perfringens sialidase-treated CHO cells (Supplementary Fig. 2B) suggesting that the unmasking of some sialoglycoconjugates at the CHO cell surface by sialidases would allow NDV to fuse more efficiently.

Fig. 2.

Effect of sialic acid depletion on NDV fusion and binding. a Cells were incubated in the presence of V.cholerae- (25 mU/ml), C.perfringens- (50 mU/ml) or A. ureafaciens- (25 mU/ml) sialidases for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing, 3 μg of R18-labeled NDV was bound to cells for 1 h at 4 °C, after which they were allowed to fuse for 1 h at 37 °C. Fusion was assessed by the transfer of the R18 red dye to the cell membrane and is referred to as the percentage of fusion in comparison with the control. Data are means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments. b Cells were incubated with one of the three sialidases as in a, and the binding of NDV to target cells was analyzed by a FACS-based immunoassay, as detailed in Methods. Data referring to binding percentages of the controls are means±standard deviations of three independent experiments, except those of sialidase from A.ureafaciens. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired t test: **, p < 0.01, highly statistically significant; ***, p < 0.001, extremely significant

The binding of NDV to target cells was also sensitive to sialic acid removal (Fig. 2b); including GM95 and Lec1, the treatment of cells with both α2,3 sialidases reduced the level of viral binding from 30 % to 50 %, depending on the cell line. A.ureafaciens sialidase treatment of ELL-0 cells also elicited the reduction of NDV binding by about 20 % in comparison with the controls. In general, binding reduction after sialidase treatments was lower than the inhibition of fusion (Fig. 2b versus Fig. 2a) suggesting the absence of a total correlation between the receptors involved in binding with those that promote fusion. Another possibility lies in the differences in the methodology used to analyze both activities. Moreover, the incomplete inhibition of NDV binding after sialidase treatment of cells would potentially indicate a role for additional molecules, sialylated or not, since not all sialic acids are accessible to sialidases [45]. Using an in vitro assay, we have previously reported the interaction of NDV with gangliosides with sialic acid residues attached to internal sugars, such as in GM1 or GD1b [25]. The hydrolysis therefore of external sialic acid from disialo- or trisialo- gangliosides such as GD1a or GT1b would afford gangliosides such as GM1 and GD1b respectively (for a schematic representation of ganglioside structures, see Supplementary Fig. S3), which might be used for NDV binding but, hypothetically, not for fusion. Owing to the increase in the FITC-MALI staining of CHO cells (Supplementary Fig. S2B) after α2,3 sialic acid removal as well as the increase in NDV fusion (Fig. 2a), an increase in viral binding was also expected. However, the data revealed a reduction in NDV binding of about 30 % as compared with the controls after sialidase treatments (Fig. 2b) of this cell line. It could be speculated that certain non-productive binding sites could have been removed after sialidase treatment, and then new productive binding sites could have been unmasked to allow viral fusion to occur more effectively. Major differences in fusion after α2,6 sialidase treatment were observed in ELL-0 and CHO cells (Fig. 2a). In spite of the low level of α2-6-linked sialic acids in CHO cells (Fig. 1), the fusion and binding of NDV to A.ureafaciens sialidase-treated CHO cells increased. The enzyme shows a preference for α2-6-linkages, although it may also hydrolyze α2-3-, α2-8- and α2-9-linked sialic acids [42], and hence NDV would have more opportunities to bind to receptor-depleted CHO cells without competition from the sialic acid moieties removed by the sialidase on the same cell surface.

The effect of sialic acid removal on NDV infectivity was also studied. Before infection, cells were treated with sialidase from V.cholerae, which showed the highest fusion inhibition effect in most of the cell lines of this study (Fig. 2a). Following this, control and desialylated cells were infected with three different concentrations of rNDV-F3aa-mRFP recombinant NDV. As detailed in Methods, infectivity was monitored at 24 h post-infection, calculating the percentage of the red-fluorescent infected cells from the total number of cells. The results are summarized in Fig. 3. At the highest viral concentration assayed (10−2 dilution), the control cells were fully infected whereas no inhibition of infectivity was observed, except in ELL-0 and Lec1 cells (Fig. 3a). Nevertheless, at the lowest viral concentration (10−4 dilution) infectivity was almost completely inhibited in the five cell lines (Fig. 3c). The effect of A.ureafaciens sialidase treatment of ELL-0 cells on NDV infectivity was also analyzed showing about 50 % of inhibition at both 10−3 and 10−4 viral dilutions (Fig. 3d). The reduction in viral infectivity exerted by sialidase treatment was dependent on the viral concentration: the higher the viral titre the lower the inhibition of infectivity. It has been established that at low viral concentrations viruses use more specific routes for entry [46, 47]; our results would suggest that the requirement of specific sialic acid residues in the initial interactions of NDV with cells may be bypassed in the presence of large concentrations of virus, as reported before for influenza virus [13]. In the N-glycoprotein-deficient cell line Lec1, it could be speculated that in the absence of specific glycoproteins the virus would always use less specific routes entry, being negatively affected by sialic acid removal at both low and at high viral concentrations. Moreover, it has been recently published that NDV may efficiently fuse and infect Lec1 cells suggesting that hybrid and complex-type N-glycans are not essential for NDV infection [48].

Fig. 3.

Effect of sialic acid depletion on NDV infectivity. Cells were previously incubated in the presence of 25 mU/ml of V.cholerae- (a, b, c) or A. ureafaciens- (d) sialidases for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, several dilutions of rNDV-F3aa-mRFP recombinant NDV were added to the cells and infectivity was analyzed at 24 h post-infection by calculating the percentage of red-fluorescent cells (infected cells) out of the total number of cells in six random fields. a Dilution 10−2 (approximately a moi of 100); b Dilution 10−3 (approximately a moi of 10); c Dilution 10−4 (approximately a moi of 1). d Ell-0 cells were incubated in the presence of A.ureafaciens- sialidase and then infected with 10−3 or 10−4 dilution of rNDV-F3aa-mRFP. Data are means±standard deviations of three independent experiments

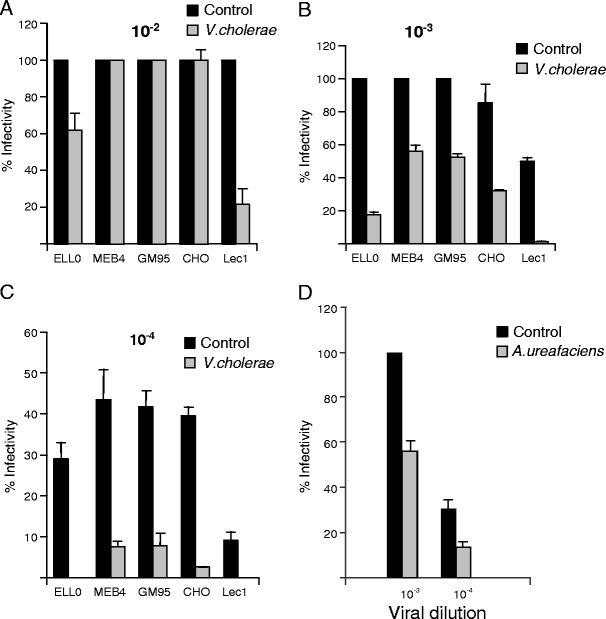

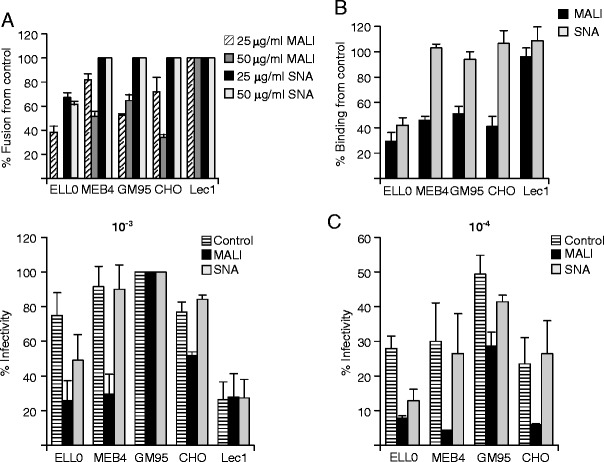

We also carried out some lectin competition assays, analyzing the effect of the preincubation of target cells with specific lectins on NDV binding, fusion and infectivity (Fig. 4). The lectin from MALI, specific for α2-3-linked sialic acids, inhibited fusion in four of the cells lines assayed in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4a). In general, these data correlate with those of sialidase fusion inhibition (Fig. 2a). Unlike the data concerning the effect of sialic acid removal on NDV fusion in CHO cells (Fig. 2a), we did detect an inhibitory effect of MALI preincubation of this cell line, observing about 70 % of fusion inhibition at the highest dose assayed. These data confirmed that α2-3-linked sialic acid-linked glycoconjugates are involved in NDV interaction with CHO cells. As expected from the data of α2-6-linked sialic acid composition and removal (Figs. 1 and 2), SNA lectin, which recognizes α2-6-linked sialic acids, only exerted a significant inhibitory effect on NDV fusion with pretreated ELL-0 cells (Fig. 4a). As a control, lentil lectin, which shows specificity for high mannose cores [49], was ineffective at blocking NDV fusion (data not shown) in any of the five cell lines studied. The data concerning viral binding after lectin preincubation were similar to those of viral fusion inhibition, showing that MALI lectin reduced NDV binding in ELL-0, MEB4 and GM95 and CHO cells (Fig. 4b), whereas no inhibition of binding was observed in Lec1 cells. Moreover, preincubation of ELL-0 cells with SNA lectin prior to NDV binding resulted in a strong reduction in viral binding, whereas, as expected, very little or no effect was seen in the other four cell lines. The negative effect of lectin preincubation on NDV infectivity shown in Fig. 4c was stronger at the lowest viral concentration (10−4 dilution), like the data concerning the effect of sialidase on NDV infectivity (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4.

Lectin competition of NDV interaction with cells. Cells were incubated in the presence 25 or 50 μg/ml of lectin from MALI or from SNA for 1 h at 4 °C, after which virus fusion - (a), see legend to Fig. 2a-, binding -(b), see legend to Fig. 2b- and infectivity –(c), see legend to Fig. 3- were analyzed. Data are means±standard deviations of three independent experiments. The observed slight reduction in viral infectivity in GM95 cells after SNA preincubation at 10−4 viral concentration was not statistically significant (p = 0.072 in the Student’s t test)

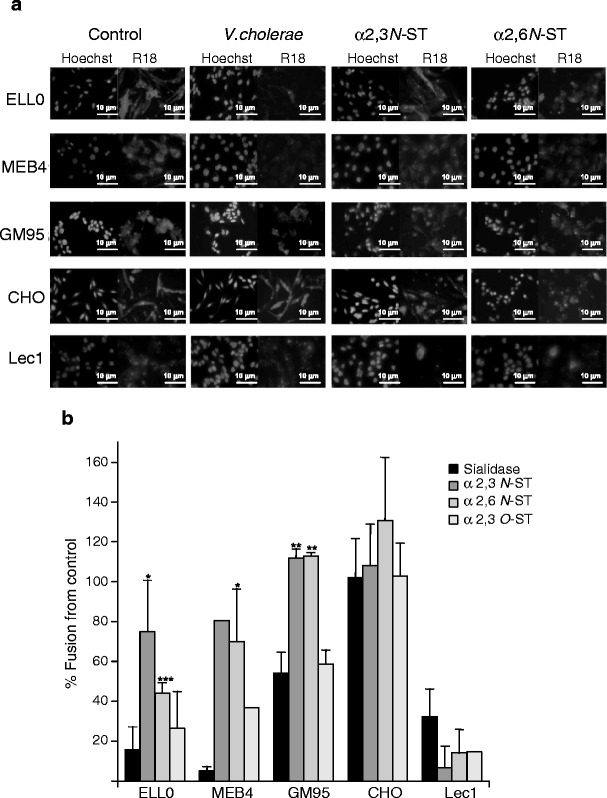

To further confirm the role of α2-3- and α2-6-linked sialic acid linkages in NDV specificity, we assayed the effect of the restoration of sialic acid by treatment of sialic acid depleted- cells with different STs in the presence of CMP-NeuAc acting as a sialic acid donor. After sialidase treatment, cells were incubated with α2,3N-, α2,6N- or α2,3O- STs to attach free sialic acid residues to the terminal position of the oligosaccharide chain with different specificities [50, 51]. The efficiency of resialylation was assessed in ELL-0 cells (Supplementary Fig. S4). The fusion of NDV with STs-treated cells was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5). The resialylation of ELL-0 cells with both α2,3N- and α2,6(N)-STs elicited a significant increase in NDV fusion, confirming the role of α2-6 sialic acid linkages NDV interactions with this cell line. Moreover, the increase in α2-6-linked sialic acids after ST resialylation in MEB4 and GM95 cells also afforded a partial restoration of the degree of NDV fusion, which would indicate that, if present, NDV may efficiently use these glycans. Resialylation with α2-3(O) ST did not restore NDV fusion, as expected from our previous data, which indicated that O-glycoproteins were not essential for NDV activities [25]. The effect of sialic acid restoration on NDV infectivity was also analyzed in ELL-0 cells. The data (Supplementary Fig. S5) show that viral infectivity was partially recovered after both ST treatments, recovery after α2,6N ST incubation being even higher. The observed differences of NDV fusion recovery in Ell-0 cells after α2,3(N)- ST treatment (75 %, Fig. 5) compared with infectivity recovery (30 %, Fig. S5) might be due to the different enzyme concentration used in both assays. Taken together, these results strengthen the conclusion that sialic acids attached with both α2-3- and α2-6- linkages are involved in NDV interactions with target cells. The interaction of NDV with α2-3- and/or α2-6-linked sialic acids might depend on the cell line, which may account for the broad cell tropism of NDV.

Fig. 5.

Effect of sialyltransferase treatments on NDV fusion. Monolayers of cells were previously desialylated by incubating them with sialidase from V.cholerae at 25 mU/ml for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, cells were incubated with α2,3(N)-, α2,6(N)- or α2,3(O)- STs at 50 mU/ml in the presence of CMP-NeuAc for 4 h at 37 °C, as detailed in Methods. Following this, 3 μg of R18-NDV was allowed to fuse for 1 h at 37 °C. a Representative microphotographs: Hoechst, nuclei staining; R18, NDV-fused cells b Percentage of fusion with respect to the controls, quantified by calculating the percentage of red-labelled cells and referred to control untreated cells. Data are means±standard deviations of three independent experiments, except those of α2,3(O)- ST for MEB4 and Lec1 cells, which are data from one experiment. Statistical analyses were performed using the paired t test: * p < 0.05 statistically significant: ** p < 0.01 very significant; *** p < 0.001 extremely significant

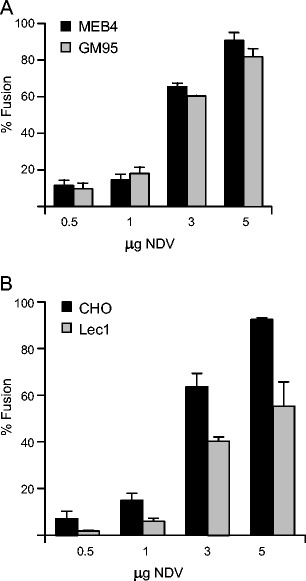

As shown in Fig. 1, MEB4 expressed approximately 4.5-fold as much α2-3-linked sialic acid as GM95, whereas Lec1 expressed 14.5-fold less sialic acids than CHO. Despite the low level of α2,3 and α2,6 sialic acid expression at the cell surface, GM95 and Lec1 cells showed a significant degree of fusion (Fig. 1) and infectivity (Fig. 3) as compared with those of their parental cell lines, MEB4 and CHO respectively. Accordingly, NDV does not appear to require a large amount of sialic acids on the cell surface to interact efficiently with the target cell. Moreover, the rate of NDV fusion with the ganglioside-deficient cell line GM95 and with its parental MEB4 was similar at different viral concentrations (Fig. 6a); the same levels of viral infectivity (Fig. 3 and data not shown) and binding (Supplementary Fig. S6A) were also observed. GM95 cells were selected from the parent MEB4 cells of B16 mouse melanoma using antibodies against ganglioside GM3 [36]. Nevertheless, it has been reported that this mutant cell line may incorporate gangliosides from serum-containing medium in the cell culture [52]. To exclude this possibility, glycolipid extraction and TLC analyses of both MEB4 and GM95 cells were performed (Supplementary Fig. S7). As reported previously [36], ganglioside GM3 was detected in MEB4 cells but we failed to detect any gangliosides in the lipid extract obtained from GM95 cells nor in GM95 cells adapted for growth in serum-free medium (data not shown), confirming that GM95 was deficient in the expression of gangliosides. These results lead us to conclude that gangliosides are not an absolute requirement for NDV fusion and infection; the fusion of NDV with GM95 cells might be dependent on N-glycoproteins or other additional factors, which would be sufficient to allow correct viral-cell interactions in the absence of glycolipids. Additionally, the fusion of NDV with the N-glycoprotein-deficient cell line Lec1 was about 30 % or 60 % lower than that seen for CHO cells, depending on the viral concentration (Fig. 6b); binding was also less efficient in the mutant cell line than in CHO (Supplementary Fig. S6B); moreover, in the absence of N-glycoproteins NDV infectivity was more dependent on sialic acid residues (Fig. 3). Upon comparing the data of NDV interactions with both mutant cell lines, GM95 and Lec1, it may be concluded that glycoproteins seem to be more critical than gangliosides for NDV interactions with the target cell. Similarly, it has been shown that influenza virus cannot infect Lec1 cells, despite undergoing binding and fusion [39]. This was interpreted in terms of the idea that influenza virus specifically requires N-linked glycoproteins for infection, gangliosides being an attachment factor that is insufficient for infection.

Fig. 6.

a Comparison of the rate of NDV fusion between MEB4 and GM95. Different concentrations of R18-NDV were bound to cells for 1 h at 4 °C, after which they were allowed to fuse for 1 h at 37 °C. Data are means±standard deviations of three independent experiments. b Comparison of the rate of NDV fusion between CHO and Lec1as in a

Virus attachment and entry into the target cells have been described as a multistep process involving interactions of viruses with different molecules at the cell surface, attachment factors, correceptors and receptors with different affinities. The use of multistage binding and entry pathways is a common feature of many viruses, where primary receptors recruit virus particles to facilitate interaction with a more specific receptor that mediates viral entry. Many viruses use sialic acid- containing glycoconjugates as attachment molecules and then bind to additional receptors for entry [53]. The recognition and binding to typical sialic acid linkages is believed to be the major determinant of viral tropism for some viruses. Viruses that bind to sialic acid show a preference for α2-3-linked sialic acids or α2-6-linked sialic acids: in influenza viruses, avian species preferentially bind to α2-3-linked sialic acids whereas human and swine viruses bind to α2-6-linked sialic acids [11, 54]. It has also been suggested that avian species may serve as potential intermediate hosts for the interspecies transmission of viruses between birds and humans [55]. It has previously been determined that sialic acid is a determinant receptor for NDV infection of the host cell (revised in [1]). Here, we have shown that NDV can productively use both α2-3- and α2-6-linked sialic acids present at the cell surface glycoconjugates. The presence of both α2-3- and α2-6-linked sialic acids in tissues from the upper respiratory tract of chickens [56] indicates that, in vivo, NDV might use both receptors to initiate infection. Different viruses also recognize both sialic acid linkages: paramyxovirus hPIV1 and hPIV3[18, 43, 57, 58]; polyomaviruses [4, 59], adeno-associated viruses [60], and even several influenza strains [61, 62]. For some viruses that recognize sialoglycoconjugates, a different role of gangliosides and glycoproteins has been proposed, and it has been suggested that binding to gangliosides is a previous, less stable and transient step than binding more specifically to N-glycoproteins [39, 52]. Nevertheless, for polyomaviruses, Qian and Tsai [63] have proposed that glycoproteins and gangliosides play opposite roles in virus entry, gangliosides being functional receptor glycoproteins acting as decoy receptors.

Knowledge of the receptors used by NDV and related viruses may be very useful for a better understanding of viral tropism and for the potential development of efficient antiviral strategies. Accordingly, the design of sialic acid-based antiviral drugs to inhibit the sialidase and/or receptor binding activity of viral attachment proteins is an important antiviral strategy for preventing virus entry.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Analysis of relative surface levels of α2,3 and α2,6 sialic acids. Cells were detached from the plates by incubation with EDTA (520 μM) at 37 °C, pelleted by centrifugation and fixed with 2.5 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing, cells were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C, either with 10 μg/ml FITC-MALI, or with FITC- FITC-SNA. Control: cells without staining. Lectin binding to cells was detected by FACS as described in Methods. A representative experiment is shown (PDF 28 kb)

Lectin binding to sialidase-treated cells. (A) Untreated (Control) and V.cholerae- (25 mU/ml) or C.perfringens- (50 mU/ml) treated cells were stained with FITC-labelled lectin from A.hypogea, which recognizes β-gal(1,3)galNAc motifs. (B) Untreated (Control) and V.cholerae- (25 mU/ml) or C.perfringens- (50 mU/ml)-treated ELL-0 and CHO cells were stained with FITC-MALI, which recognizes α2,3 sialic acids. (C) Untreated (Control) and A.ureafaciens- (25 mU/ml)-treated ELL-0 and MEB4 cells were stained with FITC- SNA, which recognizes α2,6 sialic acids (PDF 169 kb)

Schematic representation of gangliosides from the ganglio-series. ▭, Galactose; △, Glucose; ○, N.acetylgalactosamine; ▼, sialic acid; Cer, Ceramide (PDF 12 kb)

Efficiency of α2,6N ST resialylation. Monolayers of ELL-0 cells were previously desialylated by incubation with sialidases from V.cholerae or A.ureafaciens (both at 25 mU/ml) for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, cells were incubated with α2,6N ST in the presence of CMP-NeuAc for 4 h at 37 °C. After washing, cells were stained with FITC-SNA (20 μg/ml), which recognizes α2,6-bound sialic acids. Controls: untreated cells. Representative microphotographs are shown (40x) (PDF 36 kb)

Effect of sialyltransferase treatments on NDV infectivity. After V.cholerae sialic acid removal, monolayers of ELL-0 cells were incubated with α2,3N- or α2,6N- STs at 25 mU/ml for 4 h at 37 °C in the presence of CMP-NeuAc. After washing, cells were infected with rNDV-F3aa-mRFP recombinant NDV at a dilution of 10−3(approximately a moi of 10) and viral infectivity was analyzed 24 h later. Data are means of two independent experiments (PDF 96 kb)

Comparison of the rate of NDV binding to MEB4 and GM95 (A) and to CHO and Lec1 (B) cells. Monolayers of cells were incubated with 1 moi of NDV for 1 h at 4 °C. Then, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS to remove unbound virus and were detached by incubation with 1 ml EDTA (520 μM) at 37 °C to perform FACS analysis as detailed in Methods. A representative experiment is shown (PDF 20 kb)

Ganglioside composition of MEB4 and GM95 cells. After ganglioside extraction and separation by HPTLC, as detailed in Methods, gangliosides from MEB4 and GM95 cells were visualized by spraying the plates with resorcinol reagent; St, standard mixture of commercial gangliosides GM3, GM1, GD1a and GT1b (PDF 25 kb)

Acknowledgments

L.S-F received a fellowship from the Junta de Castilla y León. This work was partially supported by grants from Junta de Castilla y León (SA009A08) to I.M.B. and from the Fondo de InvestigacionesSanitarias (FIS) (PI08/1813) cofinanced by FEDER funds from the EU to E.V. We thank Dr. Adolfo García-Sastre for providing recombinant rNDV-F3aa-mRFP NDV, and anti-F antibody; and Dr. Ronald M. Iorio for providing anti-HN monoclonal antibodies. We also thank the RIKEN cell bank for MEB4 and GM95 cell lines. Thanks are also due to N.Skinner for language corrections.

Abbreviations

- CMP-NeuAc

CMP-N-Acetylneuraminic acid

- MALI

Maackia amurensis lectin I

- MOI

Multiplicity of infection

- R18

Octadecylrhodamine B chloride

- SNA

Sambucus nigra

- ST

Sialyltransferase

- (N)

Sialyltransferase transfers sialic acid to N-linked glycans

- (O)

Sialyltransferase transfers sialic acid to O-linked glycans

References

- 1.Villar E, Barroso IM. Role of sialic acid-containing molecules in paramyxovirus entry into the host cell: a minireview. Glycoconj. J. 2006;23(1–2):5–17. doi: 10.1007/s10719-006-5433-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viswanathan K, Chandrasekaran A, Srinivasan A, Raman R, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. Glycans as receptors for influenza pathogenesis. Glycoconj. J. 2010;27(6):561–570. doi: 10.1007/s10719-010-9303-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neu U, Stehle T, Atwood WJ. The Polyomaviridae: Contributions of virus structure to our understanding of virus receptors and infectious entry. Virology. 2009;384(2):389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dugan AS, Gasparovic ML, Atwood WJ. Direct correlation between sialic acid binding and infection of cells by two human polyomaviruses (JC virus and BK virus) J. Virol. 2008;82(5):2560–2564. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02123-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delorme C, Brussow H, Sidoti J, Roche N, Karlsson KA, Neeser JR, Teneberg S. Glycosphingolipid binding specificities of rotavirus: identification of a sialic acid-binding epitope. J. Virol. 2001;75(5):2276–2287. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2276-2287.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schultze B, Cavanagh D, Herrler G. Neuraminidase treatment of avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus reveals a hemagglutinating activity that is dependent on sialic acid-containing receptors on erythrocytes. Virology. 1992;189(2):792–794. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90608-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dechecchi MC, Melotti P, Bonizzato A, Santacatterina M, Chilosi M, Cabrini G. Heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans are receptors sufficient to mediate the initial binding of adenovirus types 2 and 5. J. Virol. 2001;75(18):8772–8780. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.18.8772-8780.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levery SB. Glycosphingolipid structural analysis and glycosphingolipidomics. Methods Enzymol. 2005;405:300–369. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)05012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schnaar RL. Glycosphingolipids in cell surface recognition. Glycobiology. 1991;1(5):477–485. doi: 10.1093/glycob/1.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connor RJ, Kawaoka Y, Webster RG, Paulson JC. Receptor specificity in human, avian, and equine H2 and H3 influenza virus isolates. Virology. 1994;205(1):17–23. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers GN, Paulson JC. Receptor determinants of human and animal influenza virus isolates: differences in receptor specificity of the H3 hemagglutinin based on species of origin. Virology. 1983;127(2):361–373. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(83)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholls JM, Chan RW, Russell RJ, Air GM, Peiris JS. Evolving complexities of influenza virus and its receptors. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16(4):149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stray SJ, Cummings RD, Air GM. Influenza virus infection of desialylated cells. Glycobiology. 2000;10(7):649–658. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.7.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Londrigan SL, Turville SG, Tate MD, Deng YM, Brooks AG, Reading PC. N-linked glycosylation facilitates sialic acid-independent attachment and entry of influenza A viruses into cells expressing DC-SIGN or L-SIGN. J. Virol. 2011;85(6):2990–3000. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01705-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markwell MA, Svennerholm L, Paulson JC. Specific gangliosides function as host cell receptors for Sendai virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1981;78(9):5406–5410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markwell MA, Moss J, Hom BE, Fishman PH, Svennerholm L. Expression of gangliosides as receptors at the cell surface controls infection of NCTC 2071 cells by Sendai virus. Virology. 1986;155(2):356–364. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muthing J, Unland F. A comparative assessment of TLC overlay technique and microwell adsorption assay in the examination of influenza A and Sendai virus specificities towards oligosaccharides and sialic acid linkages of gangliosides. Glycoconj. J. 1994;11(5):486–492. doi: 10.1007/BF00731285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki T, Portner A, Scroggs RA, Uchikawa M, Koyama N, Matsuo K, Suzuki Y, Takimoto T. Receptor specificities of human respiroviruses. J. Virol. 2001;75(10):4604–4613. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4604-4613.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira L, Munoz-Barroso I, Marcos F, Shnyrov VL, Villar E. Sialidase, receptor-binding and fusion-promotion activities of Newcastle disease virus haemagglutinin-neuraminidase glycoprotein: a mutational and kinetic study. J. Gen. Virol. 2004;85(Pt 7):1981–1988. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79877-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crennell S, Takimoto T, Portner A, Taylor G. Crystal structure of the multifunctional paramyxovirus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7(11):1068–1074. doi: 10.1038/81002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaitsev V, von Itzstein M, Groves D, Kiefel M, Takimoto T, Portner A, Taylor G. Second sialic acid binding site in Newcastle disease virus hemagglutinin-neuraminidase: implications for fusion. J. Virol. 2004;78(7):3733–3741. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3733-3741.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alymova IV, Portner A, Mishin VP, McCullers JA, Freiden P, Taylor GL. Receptor-binding specificity of the human parainfluenza virus type 1 hemagglutinin-neuraminidase glycoprotein. Glycobiology. 2012;22(2):174–180. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai JC, Garcia JM, Dyason JC, Bohm R, Madge PD, Rose FJ, Nicholls JM, Peiris JS, Haselhorst T, von Itzstein M. A secondary sialic acid binding site on influenza virus neuraminidase: fact or fiction? Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(9):2221–2224. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki Y, Suzuki T, Matsunaga M, Matsumoto M. Gangliosides as paramyxovirus receptor. Structural requirement of sialo-oligosaccharides in receptors for hemagglutinating virus of Japan (Sendai virus) and Newcastle disease virus. J Biochem. 1985;97(4):1189–1199. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira L, Villar E, Munoz-Barroso I. Gangliosides and N-glycoproteins function as Newcastle disease virus receptors. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004;36(11):2344–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreira L, Villar E, Munoz-Barroso I. Conformational changes of Newcastle disease virus envelope glycoproteins triggered by gangliosides. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271(3):581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2003.03960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cantin C, Holguera J, Ferreira L, Villar E, Munoz-Barroso I. Newcastle disease virus may enter cells by caveolae-mediated endocytosis. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88(Pt 2):559–569. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.San Roman K, Villar E, Munoz-Barroso I. Mode of action of two inhibitory peptides from heptad repeat domains of the fusion protein of Newcastle disease virus. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002;34(10):1207–1220. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin JJ, Holguera J, Sanchez-Felipe L, Villar E, Munoz-Barroso I. Cholesterol dependence of Newcastle Disease Virus entry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818(3):753–761. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connolly SA, Lamb RA. Paramyxovirus fusion: real-time measurement of parainfluenza virus 5 virus-cell fusion. Virology. 2006;355(2):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mibayashi M, Martinez-Sobrido L, Loo YM, Cardenas WB, Gale M, Jr, Garcia-Sastre A. Inhibition of retinoic acid-inducible gene I-mediated induction of beta interferon by the NS1 protein of influenza A virus. J. Virol. 2007;81(2):514–524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01265-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99(12):7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladisch S, Gillard B. A solvent partition method for microscale ganglioside purification. Anal. Biochem. 1985;146(1):220–231. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90419-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rueda R, Tabsh K, Ladisch S. Detection of complex gangliosides in human amniotic fluid. FEBS Lett. 1993;328(1–2):13–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80955-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svennerholm L. Quantitative estimation of sialic acids. II. A colorimetric resorcinol-hydrochloric acid method. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1957;24(3):604–611. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ichikawa S, Nakajo N, Sakiyama H, Hirabayashi Y. A mouse B16 melanoma mutant deficient in glycolipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91(7):2703–2707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanley P, Chaney W. Control of carbohydrate processing: the lec1A CHO mutation results in partial loss of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1985;5(6):1204–1211. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.6.1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen W, Stanley P. Five Lec1 CHO cell mutants have distinct Mgat1 gene mutations that encode truncated N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I. Glycobiology. 2003;13(1):43–50. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu VC, Whittaker GR. Influenza virus entry and infection require host cell N-linked glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101(52):18153–18158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405172102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imberty A, Gautier C, Lescar J, Perez S, Wyns L, Loris R. An unusual carbohydrate binding site revealed by the structures of two Maackia amurensis lectins complexed with sialic acid-containing oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(23):17541–17548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shibuya N, Goldstein IJ, Broekaert WF, Nsimba-Lubaki M, Peeters B, Peumans WJ. The elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) bark lectin recognizes the Neu5Ac(alpha 2-6)Gal/GalNAc sequence. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(4):1596–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uchida Y, Tsukada Y, Sugimori T. Enzymatic properties of neuraminidases from Arthrobacter ureafaciens. J. Biochem. 1979;86(5):1573–1585. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ah-Tye C, Schwartz S, Huberman K, Carlin E, Moscona A. Virus-receptor interactions of human parainfluenza viruses types 1, 2 and 3. Microb. Pathog. 1999;27(5):329–336. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1999.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo Y, Rumschlag-Booms E, Wang J, Xiao H, Yu J, Guo L, Gao GF, Cao Y, Caffrey M, Rong L. Analysis of hemagglutinin-mediated entry tropism of H5N1 avian influenza. Virol. J. 2009;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo CT, Nakagomi O, Mochizuki M, Ishida H, Kiso M, Ohta Y, Suzuki T, Miyamoto D, Hidari KI, Suzuki Y. Ganglioside GM(1a) on the cell surface is involved in the infection by human rotavirus KUN and MO strains. J. Biochem. 1999;126(4):683–688. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeTulleo L, Kirchhausen T. The clathrin endocytic pathway in viral infection. EMBO J. 1998;17(16):4585–4593. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stuart AD, Eustace HE, McKee TA, Brown TD. A novel cell entry pathway for a DAF-using human enterovirus is dependent on lipid rafts. J. Virol. 2002;76(18):9307–9322. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.9307-9322.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun Q, Zhao L, Song Q, Wang Z, Qiu X, Zhang W, Zhao M, Zhao G, Liu W, Liu H, Li Y, Liu X. Hybrid- and complex-type N-glycans are not essential for Newcastle disease virus infection and fusion of host cells. Glycobiology. 2012;22(3):369–378. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kornfeld K, Reitman ML, Kornfeld R. The carbohydrate-binding specificity of pea and lentil lectins. Fucose is an important determinant. J Biol Chem. 1981;256(13):6633–6640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams MA, Kitagawa H, Datta AK, Paulson JC, Jamieson JC. Large-scale expression of recombinant sialyltransferases and comparison of their kinetic properties with native enzymes. Glycoconj. J. 1995;12(6):755–761. doi: 10.1007/BF00731235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee YC, Kojima N, Wada E, Kurosawa N, Nakaoka T, Hamamoto T, Tsuji S. Cloning and expression of cDNA for a new type of Gal beta 1,3GalNAc alpha 2,3-sialyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269(13):10028–10033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matrosovich M, Suzuki T, Hirabayashi Y, Garten W, Webster RG, Klenk HD. Gangliosides are not essential for influenza virus infection. Glycoconj. J. 2006;23(1–2):107–113. doi: 10.1007/s10719-006-5443-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith AE, Helenius A. How viruses enter animal cells. Science. 2004;304(5668):237–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1094823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gambaryan A, Yamnikova S, Lvov D, Tuzikov A, Chinarev A, Pazynina G, Webster R, Matrosovich M, Bovin N. Receptor specificity of influenza viruses from birds and mammals: new data on involvement of the inner fragments of the carbohydrate chain. Virology. 2005;334(2):276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wan H, Perez DR. Quail carry sialic acid receptors compatible with binding of avian and human influenza viruses. Virology. 2006;346(2):278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pillai SP, Lee CW. Species and age related differences in the type and distribution of influenza virus receptors in different tissues of chickens, ducks and turkeys. Virol. J. 2010;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang L, Bukreyev A, Thompson CI, Watson B, Peeples ME, Collins PL, Pickles RJ. Infection of ciliated cells by human parainfluenza virus type 3 in an in vitro model of human airway epithelium. J. Virol. 2005;79(2):1113–1124. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1113-1124.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amonsen M, Smith DF, Cummings RD, Air GM. Human parainfluenza viruses hPIV1 and hPIV3 bind oligosaccharides with alpha2-3-linked sialic acids that are distinct from those bound by H5 avian influenza virus hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 2007;81(15):8341–8345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00718-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen MH, Benjamin T. Roles of N-glycans with alpha2,6 as well as alpha2,3 linked sialic acid in infection by polyoma virus. Virology. 1997;233(2):440–442. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu Z, Miller E, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. Alpha2,3 and alpha2,6N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J. Virol. 2006;80(18):9093–9103. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00895-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suzuki Y. Sialobiology of influenza: molecular mechanism of host range variation of influenza viruses. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005;28(3):399–408. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamada S, Suzuki Y, Suzuki T, Le MQ, Nidom CA, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Muramoto Y, Ito M, Kiso M, Horimoto T, Shinya K, Sawada T, Usui T, Murata T, Lin Y, Hay A, Haire LF, Stevens DJ, Russell RJ, Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ, Kawaoka Y. Haemagglutinin mutations responsible for the binding of H5N1 influenza A viruses to human-type receptors. Nature. 2006;444(7117):378–382. doi: 10.1038/nature05264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qian M, Tsai B. Lipids and proteins act in opposing manners to regulate polyomavirus infection. J. Virol. 2010;84(19):9840–9852. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01093-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Analysis of relative surface levels of α2,3 and α2,6 sialic acids. Cells were detached from the plates by incubation with EDTA (520 μM) at 37 °C, pelleted by centrifugation and fixed with 2.5 % paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing, cells were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C, either with 10 μg/ml FITC-MALI, or with FITC- FITC-SNA. Control: cells without staining. Lectin binding to cells was detected by FACS as described in Methods. A representative experiment is shown (PDF 28 kb)

Lectin binding to sialidase-treated cells. (A) Untreated (Control) and V.cholerae- (25 mU/ml) or C.perfringens- (50 mU/ml) treated cells were stained with FITC-labelled lectin from A.hypogea, which recognizes β-gal(1,3)galNAc motifs. (B) Untreated (Control) and V.cholerae- (25 mU/ml) or C.perfringens- (50 mU/ml)-treated ELL-0 and CHO cells were stained with FITC-MALI, which recognizes α2,3 sialic acids. (C) Untreated (Control) and A.ureafaciens- (25 mU/ml)-treated ELL-0 and MEB4 cells were stained with FITC- SNA, which recognizes α2,6 sialic acids (PDF 169 kb)

Schematic representation of gangliosides from the ganglio-series. ▭, Galactose; △, Glucose; ○, N.acetylgalactosamine; ▼, sialic acid; Cer, Ceramide (PDF 12 kb)

Efficiency of α2,6N ST resialylation. Monolayers of ELL-0 cells were previously desialylated by incubation with sialidases from V.cholerae or A.ureafaciens (both at 25 mU/ml) for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, cells were incubated with α2,6N ST in the presence of CMP-NeuAc for 4 h at 37 °C. After washing, cells were stained with FITC-SNA (20 μg/ml), which recognizes α2,6-bound sialic acids. Controls: untreated cells. Representative microphotographs are shown (40x) (PDF 36 kb)

Effect of sialyltransferase treatments on NDV infectivity. After V.cholerae sialic acid removal, monolayers of ELL-0 cells were incubated with α2,3N- or α2,6N- STs at 25 mU/ml for 4 h at 37 °C in the presence of CMP-NeuAc. After washing, cells were infected with rNDV-F3aa-mRFP recombinant NDV at a dilution of 10−3(approximately a moi of 10) and viral infectivity was analyzed 24 h later. Data are means of two independent experiments (PDF 96 kb)

Comparison of the rate of NDV binding to MEB4 and GM95 (A) and to CHO and Lec1 (B) cells. Monolayers of cells were incubated with 1 moi of NDV for 1 h at 4 °C. Then, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS to remove unbound virus and were detached by incubation with 1 ml EDTA (520 μM) at 37 °C to perform FACS analysis as detailed in Methods. A representative experiment is shown (PDF 20 kb)

Ganglioside composition of MEB4 and GM95 cells. After ganglioside extraction and separation by HPTLC, as detailed in Methods, gangliosides from MEB4 and GM95 cells were visualized by spraying the plates with resorcinol reagent; St, standard mixture of commercial gangliosides GM3, GM1, GD1a and GT1b (PDF 25 kb)