Purpose of work

The non-structural protein 4 (Nsp4) of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) functions as a 3C-like proteinase (3CLpro) and plays a pivotal role in gene expression and replication. We have examined the biochemical properties of PRRSV 3CLpro and identified those amino acid residues involved in its catalytic activity as a prelude to developing anti-PRRSV strategies.

The 3C-like proteinase (3CLpro) of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) was expressed in Escherichia coli and characterized. The optimal temperature and pH for its proteolytic activity were 8°C and 7.5, respectively. Na+ (1000 mM) and K+ (500 mM) were not inhibitory to its activity but Cu2+, Zn2+, PMSF and EDTA were significantly inhibitory. His39, Asp64 and Ser118 residues were identified to form the catalytic triad of PRRSV 3CLpro by a series of site-directed mutagenesis analysis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10529-010-0370-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 3C-like proteinase, Nsp4, Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus

Introduction

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) is an important disease throughout the world, leading to significant economic losses in pig production (Neumann et al. 2005; Tong et al. 2007). PRRS virus (PRRSV) was identified as the etiological agent of the disease (Thiel et al. 1993). PRRSV genome is a positive-strand RNA of approximately 15,000 nucleotides, comprising 8 open reading frames (ORFs). ORF1 is comprised of two large overlapping ORFs, ORF1a and ORF1b (Meulenberg et al. 1993; Thiel et al. 1993). ORF1a is translated directly whereas ORF1b is translated by a ribosomal frame shift, yielding a large ORF1ab polyprotein that is cleaved by virus-encoded proteinases into products related to the virus transcription and replication (Allende et al. 1999). After the autocatalytic release of nonstructural protein 1α (Nsp1α), Nsp1β and Nsp2, the remainder of the ORF1ab polyprotein is cleaved into at least 10 nonstructural proteins (Nsp3–12) by Nsp4 (Ziebuhr et al. 2000). PRRSV Nsp4 belongs to the 3C-like serine proteinases (3CLSP), or 3C-like proteinase (3CLpro). The predicted catalytic triad of PRRSV 3CLpro consists of His39, Asp64, and Ser118 (numbered according to the Nsp4 amino acid sequence) (Snijder et al. 1996). The three-dimensional structure of PRRSV 3CLpro has recently been determined by X-ray crystallography (Tian et al. 2009), which makes it possible to identify amino acid residues on its active site by using site-directed mutagenesis assay.

Ascribing to its important role in the virus life circle, PRRSV 3CLpro has been suggested as a promising target for antiviral drug design (Tian et al. 2009). The objectives of the present study were to characterize the biochemical properties of PRRSV 3CLpro and identify amino acid residues to be essential for maintaining its proteolytic activity.

Materials and methods

PRRSV strain, cell culture and protein expression system

PRRSV HuN4 strain (Tong et al. 2007), Marc-145 cells, pET-32a (+) vector, E. coli DH5α, and BL21 (DE3) were used in the present study.

Construction of plasmids

Viral RNA was isolated from Marc-145 cells infected with PRRSV and reverse transcribed using oligo(dT)18 primer. The cDNA encoding the 3CLpro was amplified by PCR from the reversely transcribed mixture with the primer pairs 3CL-F/3CL-R, in that NdeI and XhoI restriction sites were introduced at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The PCR product was placed downstream of the T7 promoter, and the resultant plasmid designated pT7HisPro. Similarly, the cDNA encoding the Nsp3′4 that covered the last 8 residues of Nsp3 and the whole sequence of Nsp4 was amplified with the primer pairs Nsp3′4-F/Nsp3′4-R, in that KpnI and HindIII restriction sites were introduced at the 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The PCR product was cloned into the pET32a vector, and the resultant plasmid was designated as pET32a-Nsp3′4. The Ser118 to Tyr mutation of the 3CLpro was introduced into pET32a-Nsp3′4 with the primer pairs Ser118 → Tyr-F/Ser118 → Tyr-R by a modified PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis method (Fisher and Pei 1997), and the resultant plasmid was designated as pET32a-Nsp3′4 (Ser118 to Tyr). The primers used in the study are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Expression and purification of PRRSV 3CLpro and pET32a-Nsp3′4 (Ser118 to Tyr)

The plasmids pT7HisPro and pET32a-Nsp3′4 (Ser118 to Tyr) were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3). The transformed cells were grown at 37°C until the concentration at A 600 reached to 0.6–0.8 and then induced with IPTG for 5 h. The purification of recombinant proteins was performed using Ni-NTA column.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Several single amino acid substitutions were introduced into the plasmid pT7HisPro by a modified PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis method (Fisher and Pei 1997). The primers used for site-directed mutagenesis are given in Supplementary Table 1. The pT7HisPro-derived plasmids with amino acid substitutions were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3). These recombinant proteins were also purified using Ni-NTA column.

Proteolytic reaction

The proteolytic enzyme (5 μM) and substrate (5 μM) were reacted in 50 μl of 50 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 100 mM NaCl for 24 h at 8°C. Details of the reaction mixtures are described in the respective sections. The reaction was stopped by the addition of a quarter volume of 5× sample buffer. The proteins were analyzed by 17.5% (v/v) SDS-PAGE. To estimate the efficiency of proteolytic cleavage, the densities of individual stained bands were scanned and calculated using BandScan version 5.0. The data of cleavage efficiency were expressed as the average values of three replicate experiments.

Results and discussion

Construction of plasmids

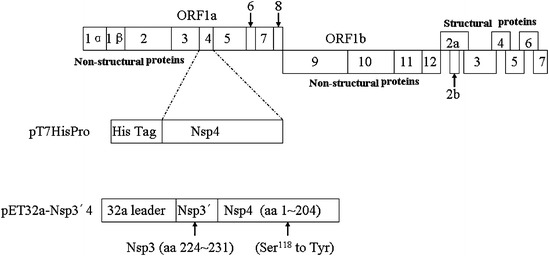

To express PRRSV 3CLpro, the plasmid pT7HisPro encoding the proteinase with His6-tag at N-terminus was constructed (Fig. 1). The 3CLpro had a calculated molecular mass of 22.4 kDa. To observe proteolysis at the cleavage site between the Nsp3 and Nsp4, pET32a-Nsp3′4 (Ser118 to Tyr) mutant protein with calculated molecular mass of 42.8 kDa) was used as the substrate, which included the N-terminal pET32a vector leader fragment, and Nsp3′4 fragment with the Tyr substitution of predicted active site Ser118 (Fig. 1). Although this protein had the 3CLpro sequence, autocatalytic cleavage did not occur because of the Ser118 to Tyr mutation. If the substrate had been cleaved at the Nsp3 and Nsp4 junction (E/G) by the active 3CLpro, pET32a-Nsp3′ moiety of 20.4 kDa and Nsp4 (Ser118 to Tyr) moiety of 22.4 kDa would be expected.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the PRRSV genome and construction of expression plasmids. ORF1a and 1b polyproteins are predicted to be cleaved into Nsp1α, Nsp1β and Nsp2 through Nsp12. The plasmid pT7HisPro was designed to encode PRRSV 3CLpro. The plasmid pET32a-Nsp3′4 was designed to cover the last 8 residues of Nsp3 and the whole sequence of Nsp4

Optimal temperature and pH for proteolytic activity

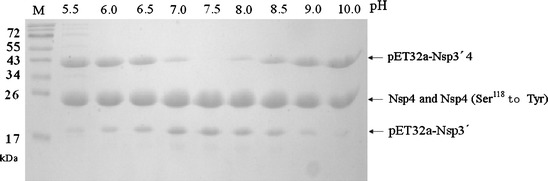

The proteolytic activity was optimal at 8°C (Fig. 2). At 4, 16, 28, 37, and 48°C, the proteolytic activity was measured as 89, 88, 87, 56, and 50% of that at 8°C, respectively. The proteolytic activity was maximal at pH 7.5 (Fig. 3); the activities were at pH 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 8.0, 8.5, 9.0 and 10.0, and were 33, 34, 56, 83, 92, 61, 34, and 22% respectively, of that at pH 7.5. These results indicated that the proteolytic enzyme had a relatively low tolerance for pH variation.

Fig. 2.

Effect of temperature on proteinase activity. The enzyme (5 μM) and substrate (5 μM) were incubated in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.0) buffer containing 100 mM NaCl for 24 h at the indicated temperatures

Fig. 3.

Effect of pH on proteinase activity. The enzyme (5 μM) and substrate (5 μM) were incubated for 24 h at 8°C in the following buffers (50 mM) containing 100 mM NaCl: citrate (pH 5.5–6.5); Tris/HCl (pH 7.0–9.0); sodium bicarbonate (10.0)

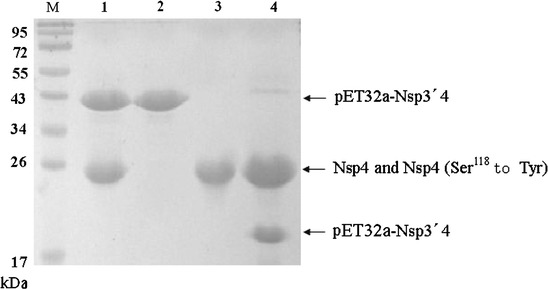

To provide further evidence that the proteolytic activity that was observed was mediated by the 3CLpro rather than by residual E. coli proteinase, the 3CLpro with the mutation of Ser118 to Tyr was incubated with the substrate for 24 h at the optimal temperature and pH. Although the substrate contained the sequence recognized by wild-type 3CLpro, it was not cleaved by the mutant proteinase (Fig. 4, lane 1), demonstrating that the proteolytic activity was mediated by PRRSV 3CLpro. Moreover, the Ser118 to Tyr mutation caused a complete loss of cleavage activity, confirming the importance of Ser118 residue as a functional element. In addition, no cleavage activity was observed in other two control reactions without either the substrate or the enzyme (Fig. 4, lane 2, 3).

Fig. 4.

Proteolytic reaction is mediated by PRRSV 3CLpro. The enzyme (5 μM) and substrate (5 μM) were incubated for 24 h at 8°C in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5) buffer containing 100 mM NaCl. Lanes 1 through 4, 3CLpro with Ser118 to Tyr mutation, substrate alone, wild-type 3CLpro alone and wild-type 3CLpro

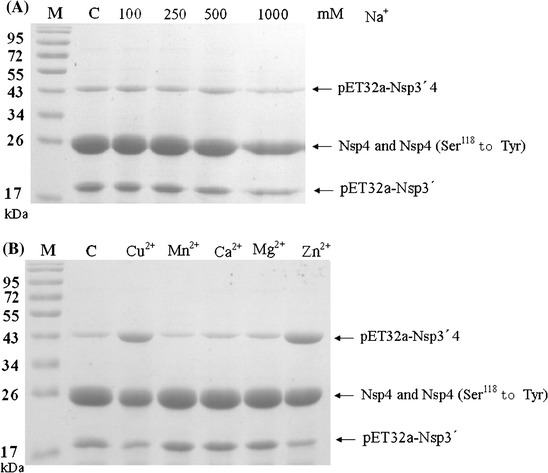

Effect of ions on proteolytic activity

The enzyme was relatively insensitive to Na+ between 100 and 500 mM. More than 83% activity was retained even at 1000 mM Na+ (Fig. 5a). In contrast with this finding in PRRSV, high concentrations of Na+ strongly inhibited the proteolytic activity of 3CLpros of the Chiba strain of Norovirus and equine arteritis virus (Someya et al. 2005; van Aken et al. 2006). K+ (500 mM) did not inhibit proteolytic activity either (data not shown). Neither did Mn2+, Mg2+ or Ca2+ at 5 mM (102, 95, and 103%, respectively), suggesting that PRRSV 3CLpro might be located or work in a confined environment inside infected cells rather than spreading throughout the whole cells. Further study is necessary to elucidate where and how PRRSV 3CLpro works in infected cells. Cu2+ and Zn2+ at 5 mM decreased the proteolytic activity to 62 or 50% (Fig. 5b). Cu2+ and Zn2+ inhibit several viral proteinases, such as 3CLpros of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus and norovirus (Hsu et al. 2004; Someya et al. 2005). These results may facilitate designing anti-PRRSV drugs that contain metal ion-conjugated compounds, which have been used in 3CL protease inhibitors for SARS-CoV (Hsu et al. 2004).

Fig. 5.

Effect of NaCl concentrations (a) and divalent cations (b) on proteinase activity. The effect of metal ions was examined by preincubating the enzyme with the compound of interest for 2 h at 8°C. Thereafter, the substrate (5 μM final concentration) was added, and the extent of cleavage was calculated after 24 h incubation at 8°C. The activity was compared with that using 50 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 7.5) without cations. (a) The reaction mixtures with the indicated NaCl concentration. (b) The reaction mixtures with 5 mM of the indicated inons. Lane C, reactions without cations

Effect of proteinase inhibitors on proteolytic activity

PMSF inhibited the proteolytic activity of PRRSV 3CLpro up to 25% (Fig. 6). EDTA showed even higher inhibitory effect (40% inhibition) than PMSF. The proteolytic activity of exfoliative toxin A, which is also a serine proteinase, has been reported to depend on Cu2+ (Sakurai and Kondo 1978). The proteolytic activity of PRRSV 3CLpro may also depend on the presence of some divalent cations. Antipain, leupeptin, TPCK, E-64 and benzamidine did not show significant inhibitory effect.

Fig. 6.

Effect of proteinase inhibitors on proteolytic activity. The 3CLpro (5 μM) in 50 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 100 mM NaCl was preincubated with different proteinase inhibitors (5 mM final concentration) for 2 h at 8°C. Thereafter, the substrate (5 μM final concentration) was added, and the extent of cleavage was calculated after 24 h incubation at 8°C. The cleavage activity in the absence of inhibitors was defined as 100%. Lane C, reaction without proteinase inhibitors. Lanes 1 through 7, reactions with antipain, PMSF, leupetin, TPCK, benzamidine, E-64 and EDTA

Mutational analysis of the catalytic site

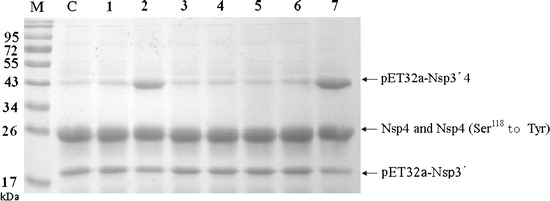

Seven single amino acid substitutions (His39 to Pro, His39 to Asn, Asp64 to Ala, Asp64 to Glu, Ser118 to Phe, Ser118 to Cys and Ser118 to Pro) were introduced into PRRSV 3CLpro by site-directed mutagenesis. The proteolytic activities of these mutant proteins were measured in the trans-cleavage assay described above. As expected, all the substitutions of amino acids His39, Asp64 and Ser118 abolished the proteolytic activity (Fig. 7). In a previous study, substitution of the predicted nucleophilic Ser118 with Ala in PRRSV 3CLpro produced an inactive enzyme (Tian et al. 2009). The X-ray crystal structure of PRRSV 3CLpro revealed that the protein folded into two β-barrel structures (domains I and II), typical of the catalytic domain of chymotrypsin-like proteinases. The canonical catalytic site was located at the opening of the cleft between domains I and II and consisted of residues His39, Asp64 and Ser118 (Tian et al. 2009). Taken together, these results supported the prediction that His39, Asp64 and Ser118 formed the catalytic triad of PRRSV 3CLpro (Snijder et al. 1996).

Fig. 7.

Mutational analysis of the predicted active site residues of PRRSV 3CLpro. The substrate was incubated for 24 h at 8°C with wild-type PRRSV 3CLpro or mutants in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5) buffer containing 100 mM. Lane C, wild-type PRRSV 3CLpro; H39P, His39 to Pro mutant; H39B, His39 to Asn mutant; D64A, Asp64 to Ala mutant; D64E, Asp64 to Glu mutant; S118F, Ser118 to Phe mutant; S118C, Ser118 to Cys mutant; S118P, Ser118 to Pro mutant

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by grants from NSFC-Guangdong Joint Foundation (U0931003), the Excellent Scientist Program of Shanghai (09XD1405400), and the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (No. 2005CB523200).

Footnotes

Ao-Tian Xu and Yan-Jun Zhou contributed equally to this study.

References

- Allende R, Lewis TL, Lu Z, et al. North American and European porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses differ in non-structural protein coding regions. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 2):307–315. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-2-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CL, Pei GK. Modification of a PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis method. Biotechniques. 1997;23:570–574. doi: 10.2144/97234bm01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JT, Kuo CJ, Hsieh HP, et al. Evaluation of metal-conjugated compounds as inhibitors of 3CL protease of SARS-CoV. FEBS Lett. 2004;574:116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulenberg JJ, Hulst MM, de Meijer EJ, et al. Lelystad virus, the causative agent of porcine epidemic abortion and respiratory syndrome (PEARS), is related to LDV and EAV. Virology. 1993;192:62–72. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann EJ, Kliebenstein JB, Johnson CD, et al. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome on swine production in the United States. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227:385–392. doi: 10.2460/javma.2005.227.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai S, Kondo I. Characterization of staphylococcal exfoliatin A as a metallotoxin, with special reference to determination of the contained metal by radioactivation analysis [proceedings] Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1978;31:208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder EJ, Wassenaar AL, van Dinten LC, et al. The arterivirus nsp4 protease is the prototype of a novel group of chymotrypsin-like enzymes, the 3C-like serine proteases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4864–4871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Someya Y, Takeda N, Miyamura T. Characterization of the norovirus 3C-like protease. Virus Res. 2005;110:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel HJ, Meyers G, Stark R, et al. Molecular characterization of positive-strand RNA viruses: pestiviruses and the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) Arch Virol Suppl. 1993;7:41–52. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9300-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X, Lu G, Gao F, et al. Structure and cleavage specificity of the chymotrypsin-like serine protease (3CLSP/nsp4) of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV) J Mol Biol. 2009;392:977–993. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong GZ, Zhou YJ, Hao XF, et al. Highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1434–1436. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.070399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Aken D, Benckhuijsen WE, Drijfhout JW, et al. Expression, purification, and in vitro activity of an arterivirus main proteinase. Virus Res. 2006;120:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebuhr J, Snijder EJ, Gorbalenya AE. Virus-encoded proteinases and proteolytic processing in the Nidovirales. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:853–879. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-4-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.