Abstract

Mononuclear leukocytes of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and regional lymphoid organs (RLOs) play a critical role in primary BTV replication and subsequent viral dissemination to distant systemic organs. The lesions in animals develop primarily as a result of vascular insult, presumably induced by the activity of viral and/or proinflammatory vasoactive mediators. Hence, the current study was designed in sheep to investigate the responses of potent vasoactivators, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and/or nitric oxide (NO) in mononuclear leukocytes of PBMCs and RLOs. The results show that BTV infection of sheep led to enhanced transcription of iNOS in PBMCs and in particular RLOs. The BTV RNAs and/or antigens were readily demonstrable in these mononuclear leukocytes, suggesting the possible role of BTV in iNOS induction. Moreover, upon in vitro infection of PBMCs with BTV-23, iNOS was up-regulated in time-dependent fashion and correlated with increased NO production. The results from these in vivo and in vitro studies thus suggest iNOS and NO produced by mononuclear leukocytes may potentially contribute to vascular-related pathology of BT.

Keywords: Bluetongue virus – 23, Inducible nitric oxide synthase, Nitric oxide, Peripheral blood mononuclear cells, Regional lymphoid organs, Pathogenesis

Introduction

Bluetongue (BT) is a non-contagious re-emerging disease of sheep, cattle and other ruminants (MacLachlan and Guthrie 2010). It is caused by bluetongue virus (BTV), which belongs to the genus Orbivirus and family Reoviridae (Maan et al. 2007). BT transmission usually occurs by the bite of Culicoides vector. At present, 26 serotypes have been identified worldwide (Maan et al. 2012). In the last decade, partly due to climatic changes, at least nine serotypes in Europe and eight serotypes in America have caused outbreaks (MacLachlan et al. 2009; MacLachlan and Guthrie 2010). BT is endemic in India, and more than 21 serotypes have been identified with BTV-23 being the most prevalent one (Dahiya et al. 2004; Maan et al. 2007; Ramakrishnan et al. 2006). As BT is an economically important disease and factored in the international movement of animals and trade (MacLachlan and Osburn 2006), Indian Council of Agricultural Research has launched an All India Network Program on BT to study its pathogenesis, epidemiology, prevention and control.

Despite BTV’s widespread distribution and recent re-emergence, BT pathogenesis is less defined. Upon intradermal inoculation by Culicoides vector, BTV infects mononuclear leukocytes, such as dendritic cells, and travel to regional lymphoid organs where primary replication occurs (Barratt-Boyes and MacLachlan 1995; Hemati et al. 2009; Umeshappa et al. 2011b). Through infected mononuclear leukocytes, BTV disseminates systemically to different organs and undergoes second round of replication principally in endothelial cells of distant systemic organs, which likely results in vascular insult and its associated lesions in multiple organs (Drew et al. 2010a, b; Hemati et al. 2009; MacLachlan et al. 2009). As mononuclear leukocytes chiefly involve in BTV primary replication and its systemic dissemination, the molecules, particularly proinflammatory and vasoactive mediators secreted by these cells more likely contribute to BT pathogenesis. Indeed, previously it was reported from both in vivo and in vitro studies that BTV-infected mononuclear leukocytes (dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes and some lymphocytes) secrete numerous proinflammatory cytokines, including IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-12, TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-8 (Channappanavar et al. 2011; Drew et al. 2010b; Hemati et al. 2009; Schwartz-Cornil et al. 2008; Umeshappa et al. 2010a, b, 2011a). Although such response is required for viral clearance, depending on type of disease, it may also damage tissues in severe cases, contributing to the disease pathogenesis (Reiss and Komatsu 1998).

Previously, the in vitro study in bovine primary cultures has shown that endothelial cells may be important source of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) (DeMaula et al. 2002a, b). Although NOS produced by endothelial cells is normally required for vascular homeostasis (Moncada and Higgs 2006), studies have suggested that BTV-induced NOS may be an important contributor for BT pathogenesis (DeMaula et al. 2002a, b). In addition to this source, inducible NOS (iNOS) produced by BTV-infected immune cells could also contribute to BT pathogenesis since it mediates variety of vascular-related pathological changes in organs (Koh et al. 2004; Reiss and Komatsu 1998). Hence, to understand the potential role of immune cell-derived iNOS and nitric oxide (NO) in BT pathogenesis, we performed both in vivo and in vitro studies in mononuclear leukocytes of natural host, sheep.

Materials and methods

Experimental approach

A detailed experimental design being followed has been reported previously (Umeshappa et al. 2011b). In brief, 6 ml of eleventh-passaged BTV-23 of sheep origin, having titer 105.5 TCID50/ml, was inoculated intravenously (n = 8; GrIV) or intradermally (n = 8; GrID) to healthy, adult sheep of both sexes. Four animals were injected similarly with sterile PBS and kept as negative controls (GrC). All the sheep used were tested sero-negative by c-ELISA (Bluetongue Antibody Test Kit, c-ELISA, VMRD, USA). The experiments were performed as per the guidelines of the Institute Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC).

One sheep from each test group on 4, 8, 16 and 22 days post-infection (DPI) and two sheep from control group on 8 and 22 DPI were sacrificed by humane method and subjected to systemic necropsy, particularly of lung, pulmonary artery, pre-scapular draining lymph node (PDLN), spleen and skin. The representative tissue pieces from spleen in GrIV and PDLN in GrID were separately collected in 10 % buffered formalin for histopathology, buffered glycerin for virus isolation, and RNAlater for RNA extraction. At different intervals, the blood samples were collected in EDTA (1–2 mg/ml) for gene expression, and virus detection and isolation studies.

Quantification of iNOS mRNA expression in PBMCs, and RLOs by qRT-PCR

At each interval (0, 1, 3, 7, 15 and 21 days post-infection), 5 ml of heparinized blood was collected aseptically from jugular vein of GrID, GrIV and GrC animals. PBMCs were separated using Histopaque-1.077 (Sigma Diagnostics Inc., USA), treated with RBC lysis buffer to remove residual RBCs and stored in TRIZOL® Reagent (1 × 106 cells/sample) (Life Technology, USA) at −80 °C until further use. Small pieces (30 mg) covering medulla and cortex region of PDLN from GrID and spleen from GrIV were collected and stored in RNA stabilizationn reagent (RNAlater, Ambion, USA) and stored at −80 °C until further use.

To further validate whether iNOS expression by leukocytes in the infected animals is virus-specific response and its biological effect of inducing NO, we carried out in vitro study as described previously (Umeshappa et al. 2011a). Briefly, PBMCs were purified from naïve sheep peripheral blood (n = 5). PBMC samples from 3 sheep were infected with BTV-23 at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 while PBMC samples from 2 sheep were kept as negative controls. Each sample was used in triplicates in the experiment. The samples were harvested at different time points, and stored in TRIZOL® Reagent at −80 °C until further use. Using the same animals, the experiment was repeated on the following day.

Total RNA extraction was carried out from PBMCs and tissue samples (PDLN and spleen) using TRIZOL® Reagent and QIAGEN tissue RNA isolation kit (Qiagen RNeasy kit, USA), respectively. The possible traces of genomic DNA in samples were removed by treating with 5 U of RNase-free DNase (Promega, USA). 2 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed using Reverse Transcription System and random primers (Promega, USA) following manufacturer’s protocols. Using β-actin primers, some of the cDNA samples were randomly selected from control and infected groups and tested for their quality and integrity.

For relative quantification of iNOS expression, quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out in Mx3000P™ system (Stratagene, USA) using 1 μl of cDNA with 0.6 μM of each primer in a final reaction volume of 25 μl containing 1× QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR master mix (QIAGEN GmBH, Germany). The primers used to amplify ovine iNOS (forward, TCTGTGCTTTTGCTCACGAC and reverse, GGGATCTCAATGTGGTGCTT) were designed from GenBank-published accession number AF223942.1. The primers used to amplify house-keeping gene, β-actin, PCR cycling conditions, and other procedures were as previously described (Umeshappa et al. 2010b). The relative expression of iNOS in BTV-23-infected tissues or PBMCs were calculated relative to un-infected control samples after normalizing to β-actin as previously described (Umeshappa et al. 2010b).

Total nitric oxide quantification by Griess reaction method

After in vitro infection of PBMCs with BTV-23, the culture supernatants were collected at different intervals and stored at −80 °C until further use. Total NO concentration in the medium was quantified by a colorimetric assay based on the Griess reaction following manufacturer’s protocol (R&D Systems, Inc., USA). Briefly, 50 μL of diluted nitrate standard or samples were added to 96-well plate, followed by 25 μL of NADH and diluted nitrate reductase, and incubated for 30 min at 37 ° C. Later, 50 μL of Griess Reagent I followed by 50 μL of Griess Reagent II were added to all the wells, and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Optical density (OD) of each well was read using a microplate reader at 540 nm wavelengths.

Results and discussion

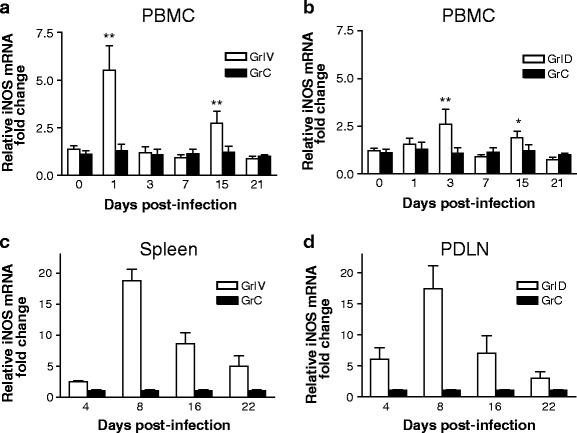

To better understand the potential role of iNOS in BT pathogenesis, PBMCs were collected from BTV-23-inoculated sheep and assessed for iNOS expression. In addition, to investigate the participation of local immune responses in RLOs, one sheep from intravenous group for spleen and one from intradermal group for PDLN collection were sacrificed on 4 critical time points, day 4, day 8, day 12 and day 16 of BTV infection. Both PBMCs and RLOs showed increased transcriptional activity of iNOS at various time points (Fig. 1a–d). Early increased expression of iNOS (>24 h) in PBMCs of GrIV is possibly due to response of blood-derived, directly infected antigen-presenting cells (APCs) owing to IV route of inoculation (Fig. 1a). In contrast, PBMCs from GrID had relatively increased iNOS expression on 3 DPI (Fig. 1b), perhaps due to reactive APCs that have disseminated from PDLN. It is not known why iNOS expression decreased considerably on 7 DPI and increased modestly on 15 DPI in both the groups. It is likely due to biological phenomenon rather than individual sheep variation. It is possible that infected reactive APCs and other mononuclear leukocytes might migrate into RLOs from circulation or die by 7 DPI owing to their shorter lifespan. On the other hand, by 15 DPI, BTV-activated CD8± T cells, which reach peak during 10 to 15 DPI (Umeshappa et al. 2010b), might contribute to increased levels of iNOS. In support of these, Ag-specific CD8± T cells have shown to express iNOS to mediate their effector functions (Choy et al. 2007, 2008). Indeed, during this period, both the groups showed rapid decrease in the clinical scores (Umeshappa et al. 2011b), and reduced positivity of BTV, suggesting iNOS and NO could influence adaptive cellular immune responses against BTV.

Fig. 1.

BTV-23 induces iNOS expression in PBMCs, and RLOs (PDLN and spleen). Following BTV-23 inoculation, the expression of iNOS was studied in PBMCs (a) and spleen (c) of GrIV, and PBMCs (b) and PDLN (d) of GrID at the indicated time points. In a and b, graphs represent relative fold changes (mean ± S.D) of iNOS in PBMCs of BTV-23-infected sheep relative to the un-infected control sheep. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism 3.0. The means of infected test (n = 5) and naïve control (n = at least 4) PBMCs were compared by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Note For statistical analysis purpose, PBMCs collected before BTV inoculation from some of the test groups were also used as uninfected control samples. In c and d, graphs represent relative fold changes (mean ± S.D) of iNOS in spleen of GrIV (c) and PDLN of GrID (d)

Similarly, BTV-23 infection led to considerable expression of iNOS in RLOs up to 16 DPI both in GrID and GrIV (Fig. 1c and d). The iNOS appeared to follow similar kinetics in both the groups on all time points except on 4 DPI, where PDLN from GrID had substantial iNOS expression when compared to spleen of GrIV. In both the groups, the expression was peaked on 8 DPI and declined later. In contrast to PBMCs, RLOs had considerably enhanced persistent activity, suggesting they may form important contributors of iNOS and possibly NO in BTV infection. The upregulation of iNOS in RLOs is likely due to preferential homing of mononuclear leukocytes, which once infected migrate to lymphoid organs where primary BTV replication and initiation of immune responses occur. Indeed, it has been shown that, during early infectious period, NO produced by iNOS, perhaps in innate immune cells, modulates adaptive immune responses by favoring Th1 and effector CD8+ T cells generation (Diefenbach et al. 1999; Vig et al. 2004). Consistent with iNOS expression, spleen in GrIV and PDLN in GrID had gross and microscopic lesions characteristics of vascular changes (Umeshappa et al. 2011b). Briefly, the lesions reached peak degree on 8 DPI in both the groups. Grossly, spleens of both the groups were congested and slightly enlarged. On the other hand, only PDLN from GrID showed mild to moderate degrees of enlargement and congestion. Microscopically, the affected spleen and PDLN were characterized by relatively increased MNC infiltration, congestion and edematous changes when compared to control ones. Furthermore, these RLOs were positive for BTV by isolation and/or real time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR), and direct FAT methods (Umeshappa et al. 2011b). Although the results of RLOs are derived from a single sheep on a given interval, they still indicate some degree of association between BTV presence, clinical lesions and iNOS expression in mononuclear leukocytes as hight iNOS expression was observed only after BTV inoculation when peak clinical signs were observed, and its level declined at later stages of infection where BTV was no longer detected consistently (Umeshappa et al. 2011b). It is not sure why route of inoculation, intradermal or intravenous, appeared to have little influence on the iNOS differential expression in MNCs. One possibility could be the use of only regional lymphoid organs’ iNOS expression for comparison in this study (Umeshappa et al. 2011b). In future studies, more reliable conclusion can only be made by comparing the spleen of GrIV with spleen of GrID or PDLN of GrID with PDLN of GrIV. Since endothelial-derived iNOS is also implicated in the BT pathogenesis (DeMaula et al. 2002a, b), it is also possible that endothelial-derived iNOS might be influenced more by route of inoculation as we observed efficient dissemination of virus to different organs in GrID compared to GrIV (Umeshappa et al. 2011b).

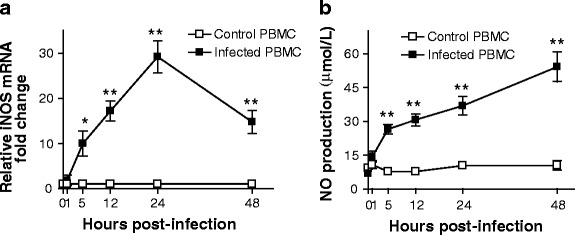

The enhanced transcriptional activity of iNOS in mononuclear leukocytes was also associated with the presence of BTV-23 as determined by isolation and/or rRT-PCR assays on the same samples (Umeshappa et al. 2011b). It was also confirmed by in vitro studies, where iNOS upregulation was observed in the infected but not in naïve ovine PBMCs (Fig. 2a). Recent study by Drew et al. (2010b) also suggested the involvement of bovine macrophages in the production of iNOS following in vitro BTV infection. Indeed, many viruses, including poxviruses, picornaviruses, retroviruses, flaviviruses, coronaviruses, etc., have known to induce iNOS and NO from immune cells (Reiss and Komatsu 1998). Mechanistically, as iNOS is only inducible from immune cells, BTV might upregulate iNOS in mononuclear leukocytes by inducing various other proinflammatory mediators, such as TNF-α and IFNs, which are potent inducers of iNOS in immune cells (Reiss and Komatsu 1998). In support of these observations, previously we and other groups have showed the increased activity of proinflammatory mediators, including IFN-γ, IFN-α, TNF-α, IL-12 and IL-1, by both in vivo and in vitro experiments (Channappanavar et al. 2011; Hemati et al. 2009; Umeshappa et al. 2010a, b, 2011a;). In particular, BTV is potent inducer of IFN-α (Foster et al. 1991; Jameson et al. 1978; Umeshappa et al. 2010a) and thus might mediates iNOS and NO production via upregulating IFN-α (Mattner et al. 2000; Rothfuchs et al. 2001). The considerable reduction in BTV viral load was also observed in some of these experiments on 15 DPI onwards, suggesting the involvement of one or several proinflammatory cytokines and other mediators in viral clearance (Umeshappa et al. 2010a, 2011b). Future work should focus on determining the relative contributions of innate versus adaptive immune cells for viral defense or organ pathology.

Fig. 2.

BTV-23-induced iNOS correlates with NO production in PBMCs. PBMC cultures from BTV-sero-negative sheep were infected with BTV-23 at 0.1 MOI, and the iNOS expression (a) and NO production (b) were studied at the indicated intervals. Graphs represent cumulative relative fold changes (mean ± S.D) in iNOS expression (a), or NO production (b) in BTV-23-infected PBMCs (n = 3) relative to the un-infected control (n = 2) samples of two independent experiments. In each experiment, PBMCs of each sheep were used in triplicates. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using GraphPad Prism 3.0. The means of infected test and naïve control PBMCs were compared by Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01

To confirm whether iNOS expression correlates with NO production, PBMCs were harvested from naïve sheep and infected with BTV-23 in vitro. At different intervals, PBMCs and their culture supernatants were harvested and analyzed for iNOS expression and NO production, respectively. Similar to in vivo responses, BTV-23 induced significant up-regulation of iNOS in PBMCs from 5 through 48 h post-infection (HPI) (Fig. 2a). Consisting with these results, Drew et al. (2010b) also reported the production of iNOS in bovine monocyte-derived macrophages although studied only up to 24 HPI. However, the level of iNOS expression appears to be slightly higher in their studies, presumably due to use of purified population of macrophages in contrast to the use of PBMCs, which contains only fraction of iNOS-producing mononuclear leukocytes (Monocytes, CD8± T cells etc.,) in our study. It appears that there is some degree of association between in vitro and in vivo studies (at least with GrIV) in the kinetics of iNOS in PBMCs. Similar to in vivo response, PBMCs of GrIV showed peak response on 24 DPI, perhaps due to direct infection of these cells. On the other hand, late iNOS expression in PBMCs of GrID is possibly due to late entry and infection of PBMCs as intradermally infected BTV has to multiply and amplify locally in lymphoid organs in DCs and other APCs before reaching circulation (Hemati et al. 2009). Finally, it is worth noting that NO production was also observed, and it was correlated well with the iNOS expression in PBMCs (Fig. 2), suggesting the possible role of iNOS in NO production from BTV-infected mononuclear leukocytes.

NO is produced in two distinct NOS isoforms: a constitutive form, predominantly in endothelial (NOS-3) and neuronal cells (NOS-1); and an inducible form, predominantly in macrophases, DCs and Ag-activated CD8+ T cells (NOS-2) (Li and Forstermann 2000; Reiss and Komatsu 1998). In contrast to many other viral infections, where immune cells alone generally contribute to iNOS, in BT and perhaps in many other hemorrhagic viral diseases, both BTV-infected endothelial and immune cells appear to contribute to significant source of iNOS. In our study, iNOS expression in RLOs is likely derived from both mononuclear leukocytes and endothelial cells as our RLO sampling included both types of cells in the RNA preparation. Being endotheliotropic, BTV could also modulate endothelium for iNOS production. Indeed, in addition to monocyte-derived macrophages (Drew et al. 2010b), the involvement of endothelial cells as a source of iNOS has been previously shown (DeMaula et al. 2002a, b). Thus, excessively produced NO in these diseases may likely mediate range of biological responses. For instance, NO, produced by iNOS in innate immune cells, is known to modulate adaptive immune responses by favoring Th1 and effector CD8+ T cells generation (Diefenbach et al. 1999; Vig et al. 2004). On the other hand, excessive NO may also lead to severe vascular damage, leading to congestion, hemorrhage, infarction and edema of multiple organs. Indeed, the infected sheep showed mild to moderate levels of clinical signs, and gross and histopathological lesions characteristics of vascular insult in various organs, including pulmonary artery, lungs, lymphoid organs and heart muscle (Umeshappa et al. 2011b). Thus, the results of both in vivo and in vitro studies in natural host sheep suggest that iNOS and NO produced by mononuclear leukocytes in BT may modulate various aspects of BT pathogenesis, including vascular-related pathology, modulation of cellular immune responses, and clearance of BTV.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by research funding from CADRAD, IVRI, India. We thank Director, Joint Directors and Department Head, Veterinary Pathology, IVRI for providing all the facilities to carry out this research work. Financial support in the form of Junior Research Fellowship from the ICAR, New Delhi, India, to Drs. Umeshappa C.S and Channappanavar R is duly acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not have any financial conflict of interests.

Contributor Information

Channakeshava Sokke Umeshappa, Phone: +1-306-6552601, FAX: +1-306-6552635, Email: chs221@mail.usask.ca.

Karam Pal Singh, Phone: +91-581-2302188, FAX: +91-581-2302188, Email: karam.singh@rediffmail.com.

References

- Barratt-Boyes SM, MacLachlan NJ. Pathogenesis of bluetongue virus infection of cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1995;206:1322–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channappanavar R, Singh KP, Singh R, Umeshappa CS, Ingale SL, Pandey AB. Enhanced proinflammatory cytokines activity during experimental Bluetongue virus-1 infection in Indian native sheep. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2011;145:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy JC, Wang Y, Tellides G, Pober JS. Induction of inducible NO synthase in bystander human T cells increases allogeneic responses in the vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1313–1318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607731104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy JC, Yi T, Rao DA, Tellides G, Fox-Talbot K, Baldwin WM, 3rd, Pober JS. CXCL12 induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase in human CD8 T cells. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1333–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya S, Prasad G, Kovi RC. VP2 gene based phylogenetic relationship of Indian isolates of Bluetongue virus serotype 1 and other serotypes from different parts of the world. DNA Seq. 2004;15:351–361. doi: 10.1080/10425170400012941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaula CD, Leutenegger CM, Bonneau KR, MacLachlan NJ. The role of endothelial cell-derived inflammatory and vasoactive mediators in the pathogenesis of bluetongue. Virology. 2002;296:330–337. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaula CD, Leutenegger CM, Jutila MA, MacLachlan NJ. Bluetongue virus-induced activation of primary bovine lung microvascular endothelial cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2002;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(02)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach A, Schindler H, Rollinghoff M, Yokoyama WM, Bogdan C. Requirement for type 2 NO synthase for IL-12 signaling in innate immunity. Science. 1999;284:951–955. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5416.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew CP, Gardner IA, Mayo CE, Matsuo E, Roy P, MacLachlan NJ. Bluetongue virus infection alters the impedance of monolayers of bovine endothelial cells as a result of cell death. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2010;136:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew CP, Heller MC, Mayo C, Watson JL, Maclachlan NJ. Bluetongue virus infection activates bovine monocyte-derived macrophages and pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2010;136:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster NM, Luedke AJ, Parsonson IM, Walton TE. Temporal relationships of viremia, interferon activity, and antibody responses of sheep infected with several bluetongue virus strains. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:192–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemati B, Contreras V, Urien C, Bonneau M, Takamatsu HH, Mertens PP, Breard E, Sailleau C, Zientara S, Schwartz-Cornil I. Bluetongue virus targets conventional dendritic cells in skin lymph. J Virol. 2009;83:8789–8799. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00626-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson P, Schoenherr CK, Grossberg SE. Bluetongue virus, an exceptionally potent interferon inducer in mice. Infect Immun. 1978;20:321–323. doi: 10.1128/iai.20.1.321-323.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh KP, Wang Y, Yi T, Shiao SL, Lorber MI, Sessa WC, Tellides G, Pober JS. T cell-mediated vascular dysfunction of human allografts results from IFN-gamma dysregulation of NO synthase. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:846–856. doi: 10.1172/JCI21767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Forstermann U. Nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. J Pathol. 2000;190:244–254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3<244::AID-PATH575>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maan S, Maan NS, Samuel AR, Rao S, Attoui H, Mertens PP. Analysis and phylogenetic comparisons of full-length VP2 genes of the 24 bluetongue virus serotypes. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:621–630. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maan NS, Maan S, Belaganahalli MN, Ostlund EN, Johnson DJ, Nomikou K, Mertens PP. Identification and differentiation of the twenty six bluetongue virus serotypes by rt-PCR amplification of the serotype-specific genome segment 2. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclachlan NJ, Guthrie AJ. Re-emergence of bluetongue, African horse sickness, and other orbivirus diseases. Vet Res. 2010;41:35. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLachlan NJ, Osburn BI. Impact of bluetongue virus infection on the international movement and trade of ruminants. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;228:1346–1349. doi: 10.2460/javma.228.9.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclachlan NJ, Drew CP, Darpel KE, Worwa G. The pathology and pathogenesis of bluetongue. J Comp Pathol. 2009;141:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattner J, Schindler H, Diefenbach A, Rollinghoff M, Gresser I, Bogdan C. Regulation of type 2 nitric oxide synthase by type 1 interferons in macrophages infected with Leishmania major. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2257–2267. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2000)30:8<2257::AID-IMMU2257>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada S, Higgs EA. The discovery of nitric oxide and its role in vascular biology. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S193–S201. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan MA, Pandey AB, Singh KP, Singh R, Nandi S, Mehrotra ML. Immune responses and protective efficacy of binary ethylenimine (BEI)-inactivated bluetongue virus vaccines in sheep. Vet Res Commun. 2006;30:873–880. doi: 10.1007/s11259-006-3313-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss CS, Komatsu T. Does nitric oxide play a critical role in viral infections? J Virol. 1998;72:4547–4551. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4547-4551.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothfuchs AG, Gigliotti D, Palmblad K, Andersson U, Wigzell H, Rottenberg ME. IFN-alpha beta-dependent, IFN-gamma secretion by bone marrow-derived macrophages controls an intracellular bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2001;167:6453–6461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Cornil I, Mertens PP, Contreras V, Hemati B, Pascale F, Breard E, Mellor PS, MacLachlan NJ, Zientara S. Bluetongue virus: virology, pathogenesis and immunity. Vet Res. 2008;39:46. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2008023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeshappa CS, Singh KP, Nanjundappa RH, Pandey AB. Apoptosis and immuno-suppression in sheep infected with bluetongue virus serotype-23. Vet Microbiol. 2010;144:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeshappa CS, Singh KP, Pandey AB, Singh RP, Nanjundappa RH. Cell-mediated immune response and cross-protective efficacy of binary ethylenimine-inactivated bluetongue virus serotype-1 vaccine in sheep. Vaccine. 2010;28:2522–2531. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeshappa CS, Singh KP, Ahmed KA, Pandey AB, Nanjundappa RH. The measurement of three cytokine transcripts in naive and sensitized ovine peripheral blood mononuclear cells following in vitro stimulation with bluetongue virus serotype-23. Res Vet Sci. 2011;90:212–214. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeshappa CS, Singh KP, Channappanavar R, Sharma K, Nanjundappa RH, Saxena M, Singh R, Sharma AK. A comparison of intradermal and intravenous inoculation of bluetongue virus serotype 23 in sheep for clinico-pathology, and viral and immune responses. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2011;141:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M, Srivastava S, Kandpal U, Sade H, Lewis V, Sarin A, George A, Bal V, Durdik JM, Rath S. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in T cells regulates T cell death and immune memory. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1734–1742. doi: 10.1172/JCI20225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]