Abstract

Two genetically different porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) strains have been identified in the USA: US prototype (also called non-S INDEL) and S INDEL PEDVs. In February 2017, a PEDV variant (USA/OK10240-8/2017) was identified in a rectal swab from a sow farm in Oklahoma, USA. Complete genome sequence analyses indicated this PEDV variant was genetically similar to US non-S INDEL strain but had a continuous 600-nt (200-aa) deletion in the N-terminal domain of the spike gene compared to non-S INDEL PEDVs. This is the first report of detecting PEDV bearing large spike gene deletion in clinical swine samples in the USA.

Keywords: PEDV, Variant, Large S gene deletion, Clinical swine sample

Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is the causative agent of porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) that was first recorded in Europe in the 1970s [1, 2]. PEDV spread to Asia during the 1980s and 1990s and became endemic in pigs in Asian countries [3]. In 2010, a severe PED outbreak occurred in China characterized by high morbidity in pigs of all ages and high mortality in neonatal piglets [4, 5]. In 2013, PED outbreaks were reported for the first time in the USA [6] and caused substantial economic losses [7]. Subsequently, US-like PEDVs were identified in other American countries and also emerged or re-emerged in some Asian and European countries [8]. Global PEDVs exhibit significant genetic diversities. Recently, Lin et al. [8] proposed to categorize global PEDV strains into Classical, S INDEL, emerging North American non-S INDEL, and emerging Asian non-S INDEL strains. In the USA, at least two genetically different PEDV strains have been identified: the highly virulent PEDV first identified in April 2013 associated with severe PED outbreaks was referred to as ‘US prototype’ or ‘US original’ or ‘non-S INDEL’ strain [9, 10]; a clinically milder PEDV variant identified in the USA in January 2014 which was different from the original highly virulent PEDV strains, as reflected by insertions and deletions in the spike (S) gene, was designated as ‘S INDEL’ PEDV [10, 11]. In this case report, we describe, for the first time, identification of a PEDV variant with a large spike gene N-terminal domain deletion from a clinical swine sample in the USA.

Results and discussion

At the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (ISU VDL), a nucleocapsid (N) gene-based real-time RT-PCR (rRT-PCR) is routinely used for the screening detection of PEDV from clinical specimens [12–14]. If positive, a spike gene-based multiplex rRT-PCR can be further used to differentiate non-S INDEL from S INDEL PEDV strains. In February 2017, rectal swabs collected from a sow farm in Oklahoma, USA, were submitted to the ISU VDL for PEDV PCR testing. The samples were positive for PEDV by the N gene-based rRT-PCR. Subsequent PEDV S gene-based differential rRT-PCR revealed that these samples were negative for S INDEL PEDV (CT > 40) but positive for non-S INDEL PEDV. Generally, the PEDV S gene-based differential rRT-PCR gave 2–3 CT higher than the N gene-based rRT-PCR on the same sample. However, the sample #8 gave unexpected results: strong positive by N gene-based rRT-PCR (CT 15.5) but weak positive for non-S INDEL PEDV by the differential rRT-PCR (CT 36.8). To determine the possible reasons for this observation, the sample #8 and another control sample #6 (CT 18.2 by N gene-based rRT-PCR and CT 20.8 for non-S INDEL by the S gene-based differential rRT-PCR) were sequenced using next-generation sequencing technology following previously described procedures [15, 16]. The PEDV in the sample #6 (USA/OK10240-6/2017) and the sample #8 (USA/OK10240-8/2017) had whole genome sequences of 28,038 and 27,438 nucleotides in length, respectively. The sequences of these two PEDVs have been deposited into GenBank (MG334554 and MG334555). Phylogenetic analyses based on the whole genome sequences and the spike gene indicated that both OK10240-6 and OK10240-8 belong to the US non-S INDEL cluster (Fig. 1). However, compared to the OK10240-6 and other non-S INDEL PEDV strains, the OK10240-8 PEDV had a large continuous deletion of 600-nt (200-aa) in the spike gene/protein (nt ∆91–690; aa ∆31–230; Fig. 2). The remaining genome of the OK10240-8 PEDV, other than the S deletion region, had approximately 99.7% nt identity to other non-S INDEL PEDV strains. A gel-based RT-PCR [17] was used to differentiate the OK10240-8 PEDV from non-S INDEL PEDV. Twenty more samples were collected from the same farm; all of them contained non-S INDEL PEDV but none of them contained OK10240-8-like PEDV, indicating the prevalence of OK10240-8-like PEDV in swine populations may be very low. Virus isolation attempts on the sample #8 in Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) were unsuccessful. The remaining sample #8 (250 µl diluted in 2250 µl culture medium) was orally inoculated into two 10-day-old PEDV-negative piglets (10 ml/pig) but did not result in active infection.

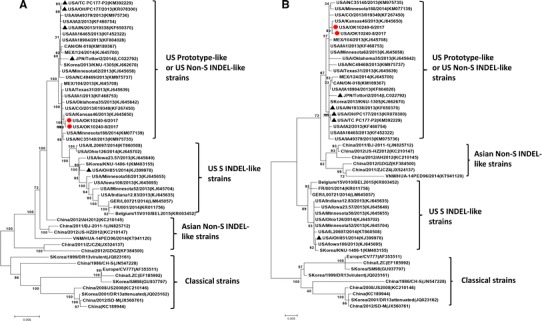

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analyses of the full-length genome (a) and partial spike gene (b) nucleotide sequences. Sequences of 50 global PEDVs were aligned using Muscle method of the software MEGA 6.06 and the maximum likelihood trees were constructed with a bootstrap analysis of 1000 replicates using MEGA 6.06 software. The number on each branch indicates the bootstrap value. The scale represents the nucleotide substitutions per site. The PEDVs OK10240-6 and OK10240-8 identified in this study are indicated with circles. The PEDV strains USA/IN19938/2013, USA/OH/PC177/2013, USA/OH851/2014, USA/TC-PC177-P2, and Japan/Tottori2/2014 included in Fig. 2 analysis are indicated with triangles

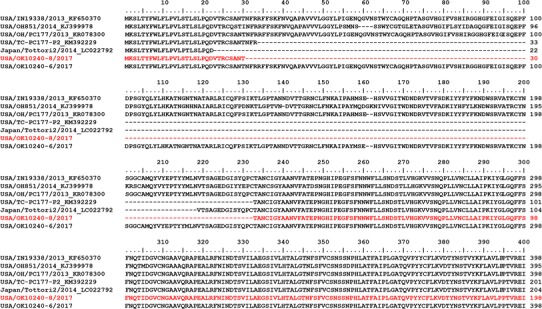

Fig. 2.

Amino acid sequence alignments of partial S protein (aa 1–398) of 7 representative PEDV strains. GenBank accession numbers are shown after each strain name. OK10240-6 and OK10240-8 are two PEDV strains identified in this study. USA/IN19938/2013, USA/OH/PC177/2013, and USA/OK10240-6/2017 are non-S INDEL PEDVs with intact S gene. USA/OH851/2014 is S INDEL PEDV. USA/TC-PC177-P2 is a cell culture-adapted PEDV isolate with 197-aa S gene deletion. Japan/Tottori2/2014 is a PEDV strain with 194-aa S gene deletion. USA/OK10240-8/2017 is a PEDV with 200-aa S gene deletion identified in a clinical swine sample

PEDV spike (S) protein is a type I membrane glycoprotein with a signal peptide (amino acid residues 1–18), a large extracellular region (aa 19–1327), a single transmembrane domain (aa 1328–1350), and a short cytoplasmic tail (aa 1351–1386) (aa positions based on PEDV strain CO13 S sequence, GenBank accession no. KF272920) [18]. The S protein assembles into homotrimers that form the club-shaped projections (spikes) on the virion surface. PEDV S protein has multiple functions including (1) mediating receptor binding through its S1 subunit (aa 1–729) and fusion of the viral and cellular membranes during cell entry through its S2 subunit (aa 730–1386); (2) harboring neutralization epitopes. Specifically, the N-terminal domain (aa 19–233) exhibits sialic acid binding activity; the receptor-binding domain (aa 501–629) is believed to interact with a protein receptor; and a fusion peptide domain (aa 891–908) mediates virus–cell membrane fusion during cell entry [18]. Neutralization epitopes have been reported within the amino acid residues 1–219, 499–638, 636–789, and 1371–1377 [19–22]. The aminopeptidase N protein (APN) serves as a receptor for several alphacoronaviruses such as canine coronavirus type II, feline coronavirus type II, transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV), and human coronavirus 229E [18]. Porcine APN was considered to be the putative receptor of PEDV with some supporting evidence [23–26]; however, some recent studies indicate that porcine APN may not be a functional receptor for PEDV [27, 28].

The N-terminal domain of PEDV S protein is one of the most variable regions in the PEDV genome. The insertions and deletions of S INDEL PEDV strains and the large deletion (aa ∆31–230) of the PEDV variant (OK10240-8) identified in this study are all located in the N-terminal domain region. It is predicted that deletion of 200-aa at this region would not interfere with either the protein receptor binding or the neutralization epitopes 499–638, 636–789, and 1371–1377. 3-D structural analyses of the S protein also suggest that this 200-aa deletion may not interfere with trimer formation. However, the neutralization epitope within residues 1–129 and the sialic acid binding activity of the virus may be affected by this 200-aa deletion. In fact, some studies have shown that PEDV strains having variations in the N-terminal domain of S protein exhibited different sialic acid binding activities [18, 29]. It remains to be determined whether the activity of sialic acid binding by the S protein affects virus entry into cells, replication in cells, and pathogenicity in pigs. In addition, 200-aa deletion in the OK10240-8 PEDV variant may affect virus virulence and pathogenicity. Construction of a recombinant PEDV carrying 200-aa deletion in this region using reverse genetics approach may help elucidate the exact effects of this 200-aa deletion.

It was previously reported [30] that a cell culture-adapted US PEDV isolate TC-PC177-P2 contained 591-nt (197-aa) deletion in the S protein (aa ∆34–230) but such deletions were not present in the original clinical sample OH/PC177/2013 (Fig. 2). A Japanese PEDV strain Tottori2/2014, identified in a clinical sample, contained 582-nt (194-aa) deletion in the S protein (aa ∆23–216) [31]. A Korean PEDV strain MF3809/2008, identified in a clinical sample, contained a 612-nt (204-aa) deletion in the S protein but in a different location (aa ∆713–916) [32]. A recent study reported the coexistence of PEDV with a large S gene deletion and PEDV with intact S gene in domestic pigs in Japan [33]. It has been demonstrated that the USA/TC-PC177-P2 and JPN/Tottori2/2014 isolates harboring a large S gene deletion are less virulent than non-S INDEL PEDVs in experimentally inoculated pigs [8, 29, 34]. In terms of TGEV, a large (224-aa) deletion in the spike gene changed the viral tropism from intestinal to respiratory and this TGEV mutant was later renamed as PRCV [35]. In contrast, the PEDV variant TC-PC177-P2 with large S gene deletion did not change intestinal tropism [8, 29].

In summary, a new PEDV variant strain (USA/OK10240-8/2017) belonging to the non-S INDEL cluster but with a 600-nt deletion (200-aa deletion) in the N-terminal domain of the S gene was identified in this study. This is the first report of a PEDV strain with a large deletion in the S gene identified in clinical swine samples in the USA. This PEDV with large S gene deletion was present on the same farm where non-S INDEL PEDV with intact S gene was detected but it appeared that the prevalence of OK10240-8-like PEDV in swine populations may be low. Additional molecular epidemiological studies are needed to monitor the emergence of novel PEDV variants and determine their prevalence levels in US swine.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory.

Author contributions

JZ supervised the work, conducted data analyses, and composed the manuscript. WYI performed RT-PCR testing. QC, YZ, and GL performed next-generation sequencing. HH attempted virus isolation. LS, WYI, and QC performed pig inoculation study. PG and KH collected clinical information of the case. WYI, QC, YZ, LS, HH, PG, KH, and GL edited the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human participants and/or animals

No human subjects were used in this study. Pigs were used in this study and the animal study protocol was approved by the Iowa State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approved number 5-17-8515-S; approved on May 12, 2017).

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Jianqiang Zhang, Phone: 1 515 2948024, Email: jqzhang@iastate.edu.

Ganwu Li, Email: liganwu@iastate.edu.

References

- 1.Oldham J. Pig Farm. 1972;10(Oct suppl):72–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pensaert MB, de Bouck P. Arch. Virol. 1978;58:243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF01317606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song D, Park B. Virus Genes. 2012;44:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0713-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li W, Li H, Liu Y, Pan Y, Deng F, Song Y, Tang X, He Q. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:1350–1353. doi: 10.3201/eid1803.120002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun RQ, Cai RJ, Chen YQ, Liang PS, Chen DK, Song CX. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:161–163. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.111259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevenson GW, Hoang H, Schwartz KJ, Burrough ER, Sun D, Madson D, Cooper VL, Pillatzki A, Gauger P, Schmitt BJ, Koster LG, Killian ML, Yoon KJ. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2013;25:649–654. doi: 10.1177/1040638713501675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cima G. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2014;245:166–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin CM, Saif LJ, Marthaler D, Wang Q. Virus Res. 2016;226:20–39. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Q, Gauger PC, Stafne MR, Thomas JT, Madson DM, Huang H, Zheng Y, Li G, Zhang J. J. Gen. Virol. 2016;97:1107–1121. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vlasova AN, Marthaler D, Wang Q, Culhane MR, Rossow KD, Rovira A, Collins J, Saif LJ. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1620–1628. doi: 10.3201/eid2010.140491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Byrum B, Zhang Y. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:917–919. doi: 10.3201/eid2005.140195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madson DM, Magstadt DR, Arruda PH, Hoang H, Sun D, Bower LP, Bhandari M, Burrough ER, Gauger PC, Pillatzki AE, Stevenson GW, Wilberts BL, Brodie J, Harmon KM, Wang C, Main RG, Zhang J, Yoon KJ. Vet. Microbiol. 2014;174:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas JT, Chen Q, Gauger PC, Gimenez-Lirola LG, Sinha A, Harmon KM, Madson DM, Burrough ER, Magstadt DR, Salzbrenner HM, Welch MW, Yoon KJ, Zimmerman JJ, Zhang J. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0139266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Tsai YL, Lee PY, Chen Q, Zhang Y, Chiang CJ, Shen YH, Li FC, Chang HF, Gauger PC, Harmon KM, Wang HT. J. Virol. Methods. 2016;234:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J, Zheng Y, Xia XQ, Chen Q, Bade SA, Yoon KJ, Harmon KM, Gauger PC, Main RG, Li G. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2017;29:41–50. doi: 10.1177/1040638716673404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Q, Li G, Stasko J, Thomas JT, Stensland WR, Pillatzki AE, Gauger PC, Schwartz KJ, Madson D, Yoon KJ, Stevenson GW, Burrough ER, Harmon KM, Main RG, Zhang J. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52:234–243. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02820-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Wang Q. J. Virol. Methods. 2016;234:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W, van Kuppeveld FJM, He Q, Rottier PJM, Bosch BJ. Virus Res. 2016;226:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C, Li W, de Esesarte EL, Guo H, van den Elzen P, Aarts E, van den Born E, Rottier PJM, Bosch BJ. J. Virol. 2017;91:e00273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00273-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang SH, Bae JL, Kang TJ, Kim J, Chung GH, Lim CW, Laude H, Yang MS, Jang YS. Mol. Cells. 2002;14:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun D, Feng L, Shi H, Chen J, Cui X, Chen H, Liu S, Tong Y, Wang Y, Tong G. Vet. Microbiol. 2008;131:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cruz DJ, Kim CJ, Shin HJ. Virus Res. 2008;132:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cong Y, Li X, Bai Y, Lv X, Herrler G, Enjuanes L, Zhou X, Qu B, Meng F, Cong C, Ren X, Li G. Virology. 2015;478:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li BX, Ge JW, Li YJ. Virology. 2007;365:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nam E, Lee C. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;144:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shan Z, Yin J, Wang Z, Chen P, Li Y, Tang L. J. Gen. Virol. 2015;96:2656. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li W, Luo R, He Q, van Kuppeveld FJM, Rottier PJM, Bosch BJ. Virus Res. 2017;235:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shirato K, Maejima M, Islam MT, Miyazaki A, Kawase M, Matsuyama S, Taguchi F. J. Gen. Virol. 2016;97:2528–2539. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou Y, Lin CM, Yokoyama M, Yount BL, Marthaler D, Douglas AL, Ghimire S, Qin Y, Baric RS, Saif LJ, Wang Q. J. Virol. 2017;91:e00227. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00227-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oka T, Saif LJ, Marthaler D, Esseili MA, Meulia T, Lin CM, Vlasova AN, Jung K, Zhang Y, Wang Q. Vet. Microbiol. 2014;173:258–269. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masuda T, Murakami S, Takahashi O, Miyazaki A, Ohashi S, Yamasato H, Suzuki T. Arch. Virol. 2015;160:2565–2568. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2522-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S, Kim S, Song D, Park B. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:2089–2092. doi: 10.3201/eid2012.131642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diep NV, Norimine J, Sueyoshi M, Lan NT, Yamaguchi R. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0170126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki T, Shibahara T, Yamaguchi R, Nakade K, Yamamoto T, Miyazaki A, Ohashi S. J. Gen. Virol. 2016;97:1823–1828. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pensaert M, Callebaut P, Vergote J. Vet. Quart. 1986;8:257–261. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1986.9694050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]