Abstract

Shigella dysenteriae causing shigellosis is one of the diseases that threaten the health of human society in the developing countries. In Shigella, IpaD gene is one of the key pathogenic genes causing strong mucosal immune system reactions. Anthrax disease is caused by Bacillus anthracis. PA protective antigen is one of the subunits in anthrax toxin complex responsible for the transfer of other subunits into the cytosol of host cells. The 20 kDa subunit of PA (PA20) has the property of immunogenicity. CTxB or B subunit of Vibrio cholerae toxin (CT) is a non-toxic protein and has the function to transfer toxic subunit into cytosol of the host cells by binding to GM1 receptor. The aim of this study was to fuse PA20, ipaD and CTxB and transform tomato plants by this cassette in order to produce an oral vaccine against shigellosis, anthrax and cholera. CTxB was used for these two antigens as an immune adjuvant. IpaD and PA20 genes were cloned in pBI121 containing the CTxB gene and Extensin signal peptide. In order to evaluate the transient expression of Shigellosis, Anthrax and Cholera antigens, agro-infiltrated tomato tissues were inoculated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens containing the gene cassette. Cloning was confirmed by PCR, enzymatic digestion and sequencing techniques. Expression of the antigens was examined by SDS-PAGE, dot blot and ELISA. Maturate green fruits demonstrated the highest expression of the recombinant proteins. The first phase of this study was carried out for cloning and expressing of CtxB, ipaD and PA20 antigens in tomato. In the next phase, we aim to analyze the immunogenicity of this vaccine candidate in laboratory animals.

Keywords: Anthrax, Cholera, Tomato, Edible vaccine, Shigellosis, Agro-infiltration

Background

Shigella is a genus from Escherichia order and the Enterobacteriaceae family that is a small, non-aerobic bacilli form, gram-negative, non-sedentary and non-sporulating bacterium. In terms of biochemical and serological properties Shigella is classified into four different categories including Shigella dysenteriae, Shigella flexneri, Shigella boydii and Shigella sonnei [1]. The main part of the mechanism of molecular pathogenesis of Shigella is the infection of host intestinal epithelial cells and intracellular survival in the epithelial environment. Pathogenesis controlling factors are coded by both plasmids and chromosomes of bacteria [2, 3]. Ipa operon contains ipA, B, C and D genes. The product of these genes are very important antigens, causing the host to show strong immune responses against Shigella. ipaD is a 37 kDa protein that recruits ipaB protein on the cell surface and triggers the invasion. This protein has been located on top of the third type of Shigella secretion system.

Bacillus anthracic is a rod-shaped Gram-positive bacterium with sporulation power. It is sedentary and grows rapidly at 37 °C [4]. Anthrax three main symptoms include skin, respiratory and digestive systems that 95% of cases reported worldwide is skin symptoms [5]. About 80% of skin type of anthrax is not an important issue and will spontaneously improve within a few weeks [6]. While 10–20% of cases, if not going to the clinical treatment, will lead to death [7].

Anthrax toxin consists of three proteins which are non-toxic in the monomeric form and when create a trimeric complex on the surface of mammalian cells, toxic form occurs. Edema factor (EF) and lethal factor (LF) enzymes are transported by the third unit called protective antigen protein (PA) to the cytosol of mammalian cells. EF is an adenylate cyclase causing Edema and impaired immune response to infection when combined with PA and injected to mammals [8, 9]. LF is a protease that cuts some of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases [10, 11]. Association of toxin subunits begins when the PA binds to a cellular receptor called receptor of anthrax toxin, a membrane protein with high expression. Then PA is cleaved into two fragments by a protease from the Furin proteases group. This enzyme removes the 20 kDa fragment of the N-terminal, while carboxyl end of the 63 kDa fragment remains attached to the cell receptors [12]. Unlike the native PA, the 63 kDa PA is oligomerized and comes in the form of a heptamer ring [13, 14]. While native PA remains on the cell surface the heptamer is transported into the cell with endocytosis [15]. Transferring non-toxic complexes to the low pH of endosomal vesicles causes 63 kDa heptamer to attach to the membrane to form a channel [16, 17]. EF and LF passing through the channel to reach the cytosol [18].

Cholera is a lethal diarrheal disease caused by a Gram-negative bacterium of Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms of cholera are mainly due to the secretion of cholera toxin called CT. The toxin is a pentameric protein with a molecular weight of 85 kDa composed of two subunits called A and B. The subunit B of cholera toxin (CTxB) with a molecular weight of 11.6 kDa binds to ganglioside GM1 receptor and facilitates the endocytosis of cholera toxin into the host cells. CTxB protein is known as an effective immunogen in the intestinal mucosa. This protein has a variety of applications including usage as an adjuvant in vaccines in which the mucosal immune response is important. It is also known as a suitable vaccine adjuvant for oral and inhalation [19, 20].

Tomato is a valuable vegetable in the Middle East and economically is in the second place in the world after potato. Original homeland of tomato is central and South America and more likely the west coast of South America. Tomato belongs to the Solanum Genus. Domestic tomato is Lycopersicum sp. Transgenic plants are a good alternative to the animal cells and prokaryotic expression systems. Transgenic plants are produced with different purposes, such as to obtain higher yield, improved quality and resistance to pests and diseases. Therefore, similarly transgenic plants can be created to express synthetic and medicinal proteins including monoclonal antibodies, antigens, vaccines, therapeutic enzymes, blood proteins, cytokines, growth factors and hormones [21]. The most important advantage of using transgenic plants is healthy aspect of their products. Transgenic plants are not host to human pathogens. Thus human pathogens such as contaminated products to hepatitis, HIV, carcinogens and bacterial toxins, etc. will not exist in transgenic plants [22]. Peptide antigens that are expressed in the edible and delicious parts of plants have led to the idea of the synthesis of active edible vaccines [23].

With this background we aimed to conjugate three pathogenic bacteria antigens to express a conjugated vaccine against three diseases in tomato plants. For this purpose, after cloning of the genes in pBI121 binary expression vector, transient gene expression evaluated by agroinfiltrated tomato leaves and fruit inoculated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens containing the genes construct. Expression of the gene cassette was examined by dot blot and ELISA techniques.

Materials and methods

Vectors used

A plant binary expression vector, pBI121 containing the Extensin signal peptide and CTxB (Fig. 1) and a pET28 plasmid containing ipaD and PA20 genes (both dedicated by University of Imam Hussain, Iran) were used in this study. These two plasmids were used for the PCR-based amplification of the three genes and further on for cloning in a single cassette and eventually, agroinfiltration experiments.

Fig. 1.

Linear and circular map of pBI_Ex-CTxB plasmid

Cloning of ipaD

A 321 bp fragment of the N-terminal region of ipaD gene was amplified by PCR using the forward and reverse primers (Table 1) harboring the restriction sites of BamHI and XhoI. Digestion of amplified ipaD and pBI_Ex-CTxB vector performed with BamHI and XhoI (Fermentase). Gel extraction was carried out with GeneAll gel extraction kit. Ligation performed by T4 DNA Ligase (Fermentase). E. coli strain DH5α competent cells prepared [24] and transformed by the recombinant plasmid. Transgenic colonies selected from the selection medium containing 50 mg/l kanamycin. Individual colonies were picked up and processed for the presence of the ipaD fragments by sequencing and digestion.

Table 1.

Primers used for amplifying and cloning of PA20 and ipaD. The underlined sequence in PA20 forward primer is relate to Linker and the red colored sequences is related to the added restriction site to the primers

| Primer | Tm | Enzyme site | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ipaD-F | 62 | BamHI | TGGGATCCCGTACCACCAACC |

| ipaD-R | 62 | XhoI | AGCTCGAGGGTGTAAGAAGACACCGCGTGC |

| PA20-F | 59 | BamHI | AGGGATCCGAAGTTAAACAGGAGAACCGG |

| PA20-R | 59 | BamHI | AGGGATCCGGTCCTGGTCCTCTTGAGTTCGAAGATTTTTGTTTTAATT |

| CTGGC |

Cloning of PA20

A 535 bp fragment of a-1 domain of PA20 was amplified by PCR with the forward and reverse primers (Table 1) containing BamHI restriction sites. The amplified fragment and plasmid were digested by BamHI. The linearized plasmid was treated with alkaline phosphatase (Fast-AP Fermentase, 1U for 1 µg plasmid) and extracted from gel (GeneAll gel extraction kit). Following transformation of the ligation product, kanamycin-resistant colonies were selected. To confirm the presence of PA20 in pBI_Ex-CTxB-PA20-ipaD vector, sequencing, PCR amplification and restriction digestion were used (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Amplification of ipaD by PCR and digestion of the recombinant plasmid. a 321 bp length of ipaD amplified by PCR and b lane 1 and 2 recombinant plasmid extracted from E. coli after cloning and lane 3 digested recombinant pBI_Ex-CTxB-ipaD plasmid with BamHI and XhoI and separation of ipaD (321 bp) from plasmid

Agroinfilteration

The recombinant vector was transformed into competent Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV-3101 strain by heat shock [25]. Kanamycin and rifampin were used to select colonies harboring recombinant plasmid and Agrobacterium (and not other possible bacteria contamination like transformed E. coli), respectively. A colony of Agrobacterium was first cultured in the LB medium containing 200 µM acetocyringone and 50 mg/l kanamycin overnight and the bacteria was pelleted at 3500 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. Pelleted bacteria were then resuspended in a 100 ml inoculation buffer and remained on the desk for 3–4 h. To evaluate the transient expression of the genes, agro-infiltration was carried out on the two-month-old tomato plant leaves, maturate green and completely red state fruits, grown in the green house. Leaves and fruits were inoculated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens via agro-injection method. In this assay inoculation medium containing 10 mM MgSo4, 10 mM MES and 200 µM acetosyringone (pH adjusted to 5.6) used for injection of Agrobacterium with a syringe. The Agrobacterium solution was injected smoothly with a needleless syringe to leaf and with a needle containing syringe to fruit pericarp tissues. Fortunately, in the injection area, Agrobacterium solution movement inside the leaf and fruit tissue was clearly seen. We tried to inject the parts (about 2 cm in diameter) of the leaf and fruit with Agrobacterium completely until saturated level, that we could not inject anymore. Finally, the areas where the solution completely injected, was carefully marked. For protein extraction assay, the places where Agrobacterium was injected and marked was precisely and carefully sampled to eliminate the non-Agrobacterium injected parts. The inoculated samples were kept in a growth chamber at 26 °C in a 16/8 h dark and light condition for 5–7 days.

Protein extraction

Inoculated leaves and fruits were sampled and used for protein extraction. The lysis buffer was prepared (Tris–HCL 0.1 M, pH = 8, Ascorbic acid 15 mM, DTT 2 mM and PVP 3%). 1 g of fine powdered samples in liquid nitrogen was poured in 3 ml of lysis buffer and completely vortexed and kept in 4 °C for 1 h. The lysate centrifuged in 4 °C for 20 min at 15,000 rpm. The supernatant retrieved and for every 1 ml supernatant 300 µl glycerol was added and stored in − 80 °C.

SDS-PAGE and dot blotting

To evaluate the transient expression of antigenes in agro-injected and intact (as control) samples, SDS-PAGE and dot blot analysis were carried out. Anti-ipaD [26] polyclonal antibodies were used as primary antibody against ipaD and goat Anti-Rabbit HRP conjugated (thermofisher, 65-6120) were used as secondary antibody against FC segment of anti-ipaD antibody. Total proteins were extracted from agro-injected leaves and fruits. Recombinant proteins were purified by Co2++ column using His-Tag present at the C-terminal of the recombinant protein and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and dot blotting.

ELISA

To perform an ELISA assay Anti-ipaD Rabbit polyclonal and goat Anti-Rabbit HRP conjugated antibodies were used as primary and secondary antibodies respectively in the presence of TMB substrate. In this experiment the ipaD protein (one of our vaccine peptide) were used to detect indirectly by two antibodies. First, the recombinant protein was coated in ELISA wells and the unbounded sites were blocked by skim milk. Anti-ipaD and further anti-human (anti-FC) antibodies used respectively for detecting the ipaD and providing signal. TMB substrate added to the reaction and after color change, reaction stopped by NaOH. Results were analyzed by ELISA reader (BioTek USA).

Results

Cloning of ipaD

A 321 bp fragment of N-terminal of ipaD was amplified using forward and reverse primers by PCR (Table 1) and analyzed on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel (Fig. 2). Figure 2b (lane 3) shows the 321 bp fragment related to ipaD that was pulled out from the recombinant pBI_Ex-CTxB-ipaD plasmid by digestion with BamHI and XhoI restriction enzymes.

Cloning of PA20

The PCR-based amplified fragment with the length of 535 bp related to PA20 gene was inserted into pBI_Ex-CTxB-ipaD plasmid between the CTxB and ipaD genes using BamHI restriction site (Fig. 3a). In order to prevent self-ligation (due to single digestion), the 5′ phosphate was removed by the alkaline phosphatase treatment. Correct cloning of PA20 in pBI_Ex-CTxB-ipaD was confirmed by sequencing and digestion (Fig. 3b). Figure 3b lane 1 shows the result of digestion of the new engineered plasmid (pBI_Ex-CTxB-PA20-ipaD) with BamHI and the presence of 535 bp fragment (PA20). Since the cloning was carried out with the single digestion, checking the orientation of insertion was necessary. Therefore, plasmids were digested with HindIII. There are two HindIII restriction sites, one in PA20 and the other in the plasmid backbone. The digestion of the recombinant plasmid led to the appearance of a 1800 bp fragment and the linearized plasmid on the agarose gel. This digestion procedure shows that the fragment had inserted into the plasmid in a correct orientation (Fig. 3b lane 2). However, digestion of non-recombinant plasmid with HindIII, led only to the conversion of circular plasmid to a linear form (Fig. 3b lane 3).

Fig. 3.

Amplification and cloning of PA20. a 535 bp of PA20 gene that amplified with PCR and b digestion of pBI_Ex-CTxB-PA20-ipaD with BamHI (lane 1) and HinDIII (lane 3). In lane 1, 535 bp of PA20 fragment separated from recombinant plasmid. In lane 3, 1800 bp fragment separated from recombinant plasmid because there was two recognition site for HinDIII, one site in PA20 and another in plasmid. Lane 4, undigested recombinant plasmid and lane 5, 535 bp PA20 amplified with PCR loaded as control

In this experiment each steps of cloning were checked and confirmed by PCR. Based on the agarose gel electrophoresis results, all fragments were exactly equal in size to predicted ones (Fig. 4; Table 2). The results on the agarose gel shows the right assembly of all inserts in the gene cassette. List of primer sequences used in this study were shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Fig. 4.

Amplification of different fragments of gene cassette. a 321 bp of ipaD (lane 1), 535 bp 0f PA20 (lane2), b PA20-ipaD 856 bp (lane 1–4), and c 1692 bp of promoter to ipaD (lane1), 1372 bp of promoter to PA20 (lane2) and 535 bp of PA20 as control (lane3)

Table 2.

The primers used in PCR reaction

| Primer | Fragment to be amplified | Size (base pair) |

|---|---|---|

| ipaD F | ||

| ipaD | 321 | |

| ipaD R | ||

| PA20 F | ||

| PA20 | 535 | |

| PA20 R | ||

| PA20 F | ||

| PA20-ipaD | 856 | |

| ipaD R | ||

| CAMV35s F | ||

| CAMV-Ex-CTxB-PA20 | 1371 | |

| PA20 R | ||

| CAMV35s F | ||

| CAMV-Ex-CTxB-PA20-ipaD | 1692 | |

| ipaD F |

Agrobacterium transformation

Recombinant plasmid was transferred into A. tumefaciens strain GV-3101 by heat shock method (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens colonies containing recombinant plasmid grown in Kanamycin (50 mg/l) and riphampin (50 mg/l) containing medium

Transient expression of recombinant protein

Greenhouse grown tomato plants were used to inject Agrobacterium into their leaves and fruits (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Injected leaves of tomato plant with Agrobacterium tumefaciens harboring the recombinant plasmid

Recombinant protein analysis

Protein extraction

Total protein was extracted from the Agrobacterium injected tomato leaves and fruits after five days from the injection (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

The method of sampling of inoculated region (pericarp) of tomato fruits for protein extraction

SDS-PAGE and dot blotting

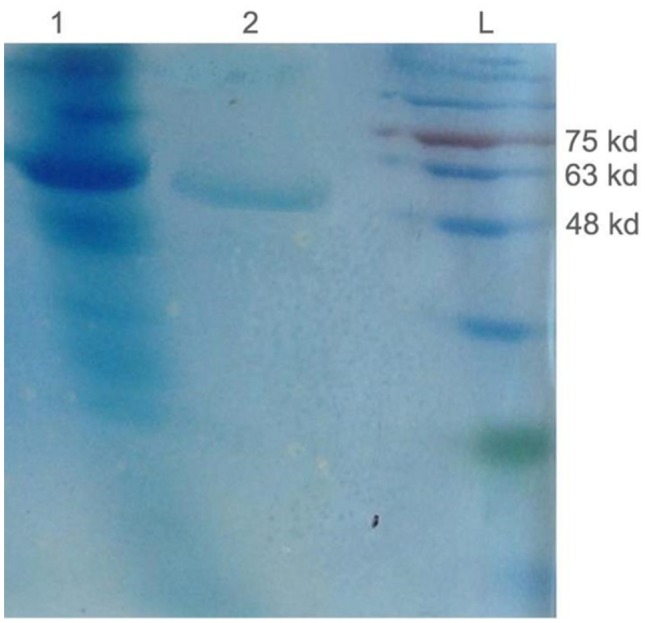

Total protein was extracted from injected and intact (as control) tissues, then recombinant proteins were purified by Co2++ column and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The 50 KD protein on the SDS-Page shows the purified recombinant protein (Fig. 8). Figure 9 shows the nitrocellulose paper with the blotted protein. The maximum coloring was detected for F. Green (green fruit). In the red fruit sample, the coloring was lower than the green fruit. This experiment revealed that recombinant protein production rate is much higher in green fruits than leaves and red fruits.

Fig. 8.

SDS-PAGE of protein. Total protein (lane 1) and recombinant protein purified with Co2+ column (lane 2) and extracted of tomato fruit, L molecular weight marker

Fig. 9.

Dot blotting of extracted protein of tomato tissues with anti-ipaD antibody

ELISA assay

The highest expression (signal) was related to the conjugation of antibody to antigen occurred in tomato green fruit in the 1/100 dilution (Fig. 10). Expression of recombinant protein in tomato red fruit and leaves are the same. No signal can observe in the control sample of non-inoculated leaves and fruits (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Data diagram obtained from ELISA reader

Discussion

Undoubtedly vaccination is an integral part of public and individual health of human in the present day. According to the pandemic and epidemic diseases like shigellosis, anthrax and cholera, vaccination against these diseases is essential for their eradication.

To produce a vaccine for these diseases, the first step is to produce the antigen. Many studies have shown that plant expression systems are quite suitable for the production of proteins. Edibility, nature friendly and no disadvantages to humans, surpasses plants compared to other expression systems such as bacteria and animal. In the present study, first ipaD and PA20 were conjugated and attached to an antigen called CTxB with adjuvant properties. Plants such as tobacco, tomato, and lettuce have been used as model plants to express various recombinant proteins. Tomato is one of the most consumed vegetables in the world with high biomass per hectare that make it a good option for production of high-scale recombinant proteins or antigens.

The reason for using tomato in this study was edibility of its fruit. Undoubtedly, the importance of the prevention of acute bloody diarrhea or shigellosis is not a secret. Strains of Shigella dysentery affect many people every year, especially childrens in developing countries.

Here we used ipaD protein that used in various studies and its immunogenicity have been demonstrated. Since Shigella have the ability to attack only to epithelial cells [27], therefore, one can immunize epithelial system by oral administration of this bacterial antigen. Studies showed that ipaD protein has the immunogenicity property and also the potential of vaccine candidate and evaluated its in-vivo immunogenicity by orally administration [28, 29].

Various studies have examined the effect of adjuvant fusion to ipaD. For example, RTB is a plant-derived adjuvant and it was used to promote the immunogenicity of ipaD [30]. RTB specially delivers the ipaD to the mucosal associated lymph tissues (MALTs). The B subunit of cholera toxin or CTxB is a pentameric, non-toxic unit of cholera toxin responsible for binding of CT to its receptor, GM1. Studies revealed that the CTxA1 subunit of CT is responsible for CT toxicity. Binding of CT to CTxB subunit makes a route that CTxA1 can move via translocation through the central channel of CTxB in the clatrin and caveolin coated vesicles to the cytosol of host cells. Most of the mammalian cells, like red blood cells and leucocytes expresses the GM1 receptor on their surface [20]. It has been shown that the CTxB acts as an adjuvant for immune system and genetically fusing this protein to an antigen improves the immune response of the host to that antigen [20, 31]. Therefore, CTxB can deliver the antigens to MALTs and facilitate its uptake by APC (antigen presenting cells). The second role for CTxB is that it can immunize the host to Vibrio cholerae. The anthrax toxin produced by Bacillus anthracic has three subunits that are not toxic to the host cells.

Protective antigen (PA) translocate Edema and lethal factors to host cell cytosol [8, 9]. PA is cleaved into two parts, including PA20, by the cell surface proteases. After this cleavage, PA20 releases into the plasma and it seems not to have any roles in disease pathogenesis or bacterial virulence. However, this protein has a diagnostic value for anthrax and can be used to induce immunity against Bacillus anthracis [32]. PA20 immunogenicity was confirmed through multiple studies in-vivo in laboratory animals [33–35]. Reason et al. showed that more than 62% of antibodies against PA antigen were specific for a-1 domain of PA or PA20 fragment and this suggest the potential of this fragment to develop as a vaccine candidate [36] even in treatment of cancer due to its capability to induce apoptosis in host cells [37] We expressed these three mentioned antigens in tomato to achieve an edible vaccine. Various studies in this field have been carried out. Demurtas et al. expressed two corona virus antigens responsible for pandemic sever acute respiratory syndrome or SARS in tobacco [38]. Chowdhury and Bagasra presented a theory that could express different life cycle antigens of malaria parasite (about 12 antigens) in tomato plant. They introduced tomato as a healthy and natural friendly plant. The suitability of the use of plants for expressing antigens and the production of edible vaccines by plant expression systems shows a bright future [39]. The first studies that were conducted on potato and tobacco and now other plants such as tomato, banana and lettuce have been put into research on the edible vaccines. Due to the short lifetime for consumption, these plants have a considerable disadvantage. The way suggested is not so complicated; drying and powdering the fresh fruits or plant tissues. In this regard, the tomato fruits expressing a particular antigen could be kept for 1 year without any decrease in the activity of the antigen [40]. Nowadays, bioinformatics analysis of proteins and antigens became an integrated steps in proteins and antigens identification [41]. Prior to experimental approaches, in a study using bioinformatics tools, we also, determined the most stable chimeric form of these three antigens (ipaD, PA20 and CTxB) in different eukaryotes and prokaryotes cells [42]. In the experimental phase of our study, in the first step, a 321 bp fragment of ipaD was inserted into plant expression binary plasmid. The second fragment (PA20) was inserted into the plasmid between ipaD and CTxB. Reverse primer of PA20 included a sequence of 12 nucleotides (proline and glycine) as a linker that was added to the C-terminal of PA20 through PCR amplification. Various investigations have used the proline-glycine linker to form a separator between two fused proteins. This sequence (linker) could be identified as the site of cleavage by the cell surface proteases like furin proteases. Delivering the fused antigens to the host cell surface by CTxB protein, makes the linker accessible to the cell surface proteases. Cleavage of this site by the proteases leads to the separation of PA20 and ipaD antigens. After the cloning procedures, we confirmed the correct sequence of recombinant plasmid by sequencing. We expressed the recombinant protein in tomato different tissues through an agro-infiltration assay. Based on the ELISA results, the expression of recombinant proteins in green fruits was 4 times higher than leaves and red fruits. Two assumptions can be made for this result. First, obviously, tomato fruits are more suitable than leaves for agro-injection by syringe, i.e. greater amounts of Agrobacterium can be injected into its pericarp tissues than leaves. Secondly, green tomato pericarp tissue is likely to be very active in protein biosynthesis. This is due to the fast growth of fruit in the green stage. In the end of fruit biomass production of tomato, development of fruit stops and ripening begins. At the ripening state protein metabolism decreases in fruits. However, our results showed that tomato fruit is a suitable choice for the expression of recombinant proteins. Since the maximum expression of antigens was observed in the green tomato fruits. The noteworthy point is that tomato fruit is consumed in a ripe and red state. the production of recombinant proteins in green fruit or leaves will not be so useful. However, it should be noted that in our gene construct a general CaMV35S promoter was used. Thus, as a suggestion for the specific expression of these proteins, a tomato fruit-specific promoter involved in ethylene biosynthesis can be used, so that these genes are activated and expressed at the time of fruit ripening.

Acknowledgement

This work was done in Agricultural Biotechnology Department of Imam Khomeini International University. We appreciate all staffs on their good collaborations.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval and informed consent were not required for this type of study.

Research involving human participants or animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Jafari Davod, Email: Jafari.dt@gmail.com.

Dehghan Nayeri Fatemeh, Phone: +982833901175, Email: nayeri@ut.ac.ir.

Hossein Honari, Email: honari.hosein@gmail.com.

Ramin Hosseini, Email: raminh_2001@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Gangarosa EJ, Perera DR, Mata LJ, Morris CM, Guzman G, Reller LB. Epidemic Shiga bacillus dysentery in Central America. II. Epidemiologic studies in 1969. J Infect Dis. 1970;122:181–190. doi: 10.1093/infdis/122.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sansonetti PJ. Rupture, invasion and inflammatory destruction of the intestinal barrier by Shigella, making sense of prokaryote–eukaryote cross-talks. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2001;25:3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasakawa C, Kamata K, Sakai T, Murayama SY, Makino S, Yoshikawa M. Molecular alteration of the 140-megadalton plasmid associated with loss of virulence and Congo red binding activity in Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun. 1986;51:470–475. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.2.470-475.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lisanby MW. Examination of the capacity of cathelicidins to control Bacillus anthracis pathogenesis. Ann Arbor: ProQuest; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnett J. Anthrax. Cuitis. 1991;48:113–114. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longfield R. Anthrax. In: Strickland GT, editor. Hunter’s tropical medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991. pp. 434–438. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lakshmi N, Kumar A. An epidemic of human anthrax—a study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1992;35:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leppla SH. Anthrax toxin edema factor: a bacterial adenylate cyclase that increases cyclic AMP concentrations of eukaryotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:3162–3166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoover D, Friedlander A, Rogers L, Yoon I, Warren R, Cross A. Anthrax edema toxin differentially regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced monocyte production of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 by increasing intracellular cyclic AMP. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4432–4439. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4432-4439.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duesbery NS, Webb CP, Leppla SH, Gordon VM, Klimpel KR, Copeland TD, Ahn NG, Oskarsson MK, Fukasawa K, Paull KD. Proteolytic inactivation of MAP-kinase-kinase by anthrax lethal factor. Science. 1998;280:734–737. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitale G, Pellizzari R, Recchi C, Napolitani G, Mock M, Montecucco C. Anthrax lethal factor cleaves the N-terminus of MAPKKs and induces tyrosine/threonine phosphorylation of MAPKs in cultured macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:706–711. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molloy S, Bresnahan P, Leppla SH, Klimpel K, Thomas G. Human furin is a calcium-dependent serine endoprotease that recognizes the sequence Arg-XX-Arg and efficiently cleaves anthrax toxin protective antigen. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16396–16402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott JL, Mogridge J, Collier RJ. A quantitative study of the interactions of Bacillus anthracis edema factor and lethal factor with activated protective antigen. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6706–6713. doi: 10.1021/bi000310u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mogridge J, Cunningham K, Lacy DB, Mourez M, Collier RJ. The lethal and edema factors of anthrax toxin bind only to oligomeric forms of the protective antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7045–7048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052160199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beauregard KE, Collier RJ, Swanson JA. Proteolytic activation of receptor-bound anthrax protective antigen on macrophages promotes its internalization. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:251–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milne JC, Collier RJ. pH-dependent permeabilization of the plasma membrane of mammalian cells by anthrax protective antigen. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:647–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blaustein RO, Koehler TM, Collier RJ, Finkelstein A. Anthrax toxin: channel-forming activity of protective antigen in planar phospholipid bilayers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2209–2213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wesche J, Elliott JL, Falnes P, Olsnes S, Collier RJ. Characterization of membrane translocation by anthrax protective antigen. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15737–15746. doi: 10.1021/bi981436i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arêas APM, Oliveira MLS, Miyaji EN, Leite LCC, Aires KA, Dias WO, Ho PL. Expression and characterization of cholera toxin B—pneumococcal surface adhesin A fusion protein in Escherichia coli: ability of CTB-PsaA to induce humoral immune response in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odumosu O, Nicholas D, Yano H, Langridge W. AB toxins: a paradigm switch from deadly to desirable. Toxins. 2010;2:1612–1645. doi: 10.3390/toxins2071612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu X, Gan Q, Clough RC, Pappu KM, Howard JA, Baez JA, Wang K. Hydroxylation of recombinant human collagen type I alpha 1 in transgenic maize co-expressed with a recombinant human prolyl 4-hydroxylas. BMC Biotechnol. 2011;11:69. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-11-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Muynck B, Navarre C, Boutry M. Production of antibodies in plants: status after twenty years. Plant Biotechnol J. 2010;8:529–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giddings G. Transgenic plants as protein factories. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2001;12:450–454. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Russell DWS (2006) The condensed protocols from molecular cloning: a laboratory manual

- 25.Hesaraki M, Saadati M, Honari H, Olad G, Heiat M, Malaei F, Ranjbar R. Molecular cloning and biologically active production of IpaD N-terminal region. Biologicals. 2013;41:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finlay BB, Falkow S. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:136–169. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.136-169.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Safaei S, Honari H, Mousavy SJ, Esmaeili A, Ghofrani M. Isolation, cloning and fusion of N-terminal region of ipaD Shigella dysenteriea and Ricin toxin B subunit. Genet 3rd Millenn. 2013;10:2880–2889. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honari H, Amlashi I, Minaee ME, Safaee S. Immunogenicity in Guinea pigs by IpaD-STxB recombinant protein. HBI J. 2013;16:83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heine SJ, Diaz-McNair J, Martinez-Becerra FJ, Choudhari SP, Clements JD, Picking WL, Pasetti MF. Evaluation of immunogenicity and protective efficacy of orally delivered Shigella type III secretion system proteins IpaB and IpaD. Vaccine. 2013;31:2919–2929. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmgren J, Lönnroth I, Månsson J, Svennerholm L. Interaction of cholera toxin and membrane GM1 ganglioside of small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:2520–2524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.7.2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmadi A, Honari H, Minaei M (2014) Cloning and expression of fusion genes of domain A-1 protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis and Shigella enterotoxin B Subunit (Stxb) in E. coil. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci 22

- 32.Demurtas OC, Massa S, Illiano E, De Martinis D, Chan PK, Di Bonito P, Franconi R. Antigen production in plant to tackle infectious diseases flare up: the case of SARS. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:54. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abboud N, Casadevall A. Immunogenicity of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen domains and efficacy of elicited antibody responses depend on host genetic background. Clin Vaccine Immunol CVI. 2008;15:1115–1123. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00015-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q, Peachman KK, Sower L, Leppla SH, Shivachandra SB, Matyas GR, Peterson JW, Alving CR, Rao M, Rao VB. Anthrax LFn-PA hybrid antigens: biochemistry, immunogenicity, and protection against lethal ames spore challenge in rabbits. Open Vaccine J. 2009;2:92–99. doi: 10.2174/1875035400902010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iyer V, Hu L, Schanté CE, Vance D, Chadwick C, Jain NK, Brey RN, Joshi SB, Volkin DB, Andra KK, Bann JG, Mantis NJ, Middaugh CR. Biophysical characterization and immunization studies of dominant negative inhibitor (DNI), a candidate anthrax toxin subunit vaccine. Hum Vaccine Immunother. 2013;9:2362–2370. doi: 10.4161/hv.25852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reason D, Ullal A, Liberato J, Sun J, Keitel W, Zhou J. Domain specificity of the human antibody response to Bacillus anthracis protective antigen. Vaccine. 2008;26:4041–4047. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hammamieh R, Ribot WJ, Abshire TG, Jett M, Ezzell J. Activity of the Bacillus anthracis 20 kDa protective antigen component. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pogrebnyak N, Golovkin M, Andrianov V, Spitsin S, Smirnov Y, Egolf R, Koprowski H. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) S protein production in plants: development of recombinant vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci Koprowski. 2005;102:9062–9067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503760102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chowdhury K, Bagasra O. An edible vaccine for malaria using transgenic tomatoes of varying sizes, shapes and colors to carry different antigens. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sala F, Rigano MM, Barbante A, Basso B, Walmsley AM, Castiglione S. Vaccine antigen production in transgenic plants: strategies, gene constructs and perspectives. Vaccine. 2003;21:803–808. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00603-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jafari D, Dehghan NF. Isolation and bioinformatics study of TbJAMYC transcription factor involved in biosynthesis of taxol from Iranian yew. Rangel For Plant Breed Genet Res. 2018;26:12–22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jafari D, Dehghan Nayeri F, Honari H, Hoseini R, Jafari R. Bioinformatic analysis of different fusions of ipaD, PA20 and CTxB antigens: a preliminary analysis for vaccine design. Genet 3rd Millenn. 2016;14:4234–4241. [Google Scholar]