Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV E gene fragment was cloned and expressed as a recombinant protein fused with a myc tag at the N-terminus in vitro and in Vero E6 cells. Similar to other N-glycosylated proteins, the glycosylation of SARS-CoV E protein occurred co-translationally in the presence of microsomes. The SARS-CoV E protein is predicted to be a double-spanning membrane protein lacking a conventional signal peptide. Both of the transmembrane regions (a.a. 11–33 and 37–59) are predicted to be α-helices, which penetrate into membranes by themselves. As expected, these two transmembrane regions inserted a cytoplasmic protein into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Either of these two transmembrane domains co-localized with M protein. Both the transmembrane domains of E protein are required to interact with M protein, while either of the hydrophilic regions (a.a. 1–10 or 60–76) is dispensable as shown by co-immunoprecipitation assay. These results are important for the study of SARS-CoV assembly.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11262-009-0341-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: SARS-CoV, E protein, Co-translational, Membrane integration, Protein–protein interactions

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), a new infectious disease typically associated with fever, shortness of breath, cough, and pneumonia, first emerged in southern China in November 2002. Within months of the outbreak, SARS had spread globally, affecting over 8,000 patients in 29 countries with 774 fatalities [1]. The etiology of SARS is associated with a newly discovered coronavirus, SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) [2]. Subsequent studies indicate that the SARS-CoV is of animal origin [3], and its precursor is still present in animal populations within the region. Although the global outbreak of SARS was contained, there are serious concerns over its re-emergence. To date, no specific treatment exists for this disease. Thus, further basic and clinical research is required for disease control.

SARS-CoV is phylogenetically distinct, and only distantly related to the other coronavirus clades [4, 5]. Coronaviruses are exceptionally large RNA viruses and employ complex regulatory mechanisms to express their genomes. The genome structure, gene expression pattern, and protein profiles of SARS-CoV are similar to those of other coronaviruses [6]. Previous studies on various coronaviruses indicate that the four structural proteins (S, E, M, and NC) play roles in virion morphogenesis [7, 8]. Moreover, it is reported that co-expression of M and E proteins together can form virus-like particles (VLPs) in different coronaviruses [9, 10]. To develop a VLP vaccine for SARS-CoV, understanding the protein–protein interactions between SARS-CoV M and E proteins is necessary. Differential maturation and subcellular localization of SARS-CoV S, M, and E proteins is also reported [11]. Both SARS-CoV M and E proteins are integral membrane proteins, though neither of them contains a conventional signal peptide [10, 11]. Expression and membrane integration of SARS-CoV M protein was characterized previously [12]. The interacting domains of SARS-CoV M with other structural proteins (S, E, and NC proteins) were also reported previously [13]. The envelope protein of coronaviruses is a small membrane protein with multiple functions. It plays important roles in virion assembly and morphogenesis, alteration of membrane permeability of host cells, and virus–host cell interactions [14]. SARS-CoV E protein also is involved in host-cell apoptosis [15], alteration of host-cell membrane permeability [16–18], and virion assembly [19].

In this report, expression and membrane integration of SARS-CoV E protein and its interaction with M protein were characterized extensively. Results from this study will help us understand more about SARS-CoV viral assembly.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The construction of the full-length membrane protein into the pcDNA3.1/V5-His A vector (Invitrogen, USA) or pcDNA3-myc vector (constructed in our laboratory) was described previously [12, 13, 20]. The construction of the plasmid expressing the full-length envelope protein fused with a myc tag (containing 10 amino acids of the myc epitope and six amino acids of junction sequences) at the N-terminus was also described previously [13].

To link the first 115 amino acids of hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein with a.a. 11–33 of SARS-CoV E protein, PCR primers (HCV-1 and CC115-AS2) were used to amplify the first 115 amino acids of the HCV core gene fragment, while PCR primers (CoE-11S and CoE-33AS3) were used to amplify the DNA fragment encoding a.a. 11–33 of SARS-CoV E protein. After PCR reaction, these two DNA fragments were digested by restriction enzymes (EcoRI/BamHI and BamHI/XbaI separately) and cloned into the pcDNA3.1/V5-His A expression vector (linearized by EcoRI/XbaI). To link the first 115 amino acids of the HCV core protein with a.a. 37–59 of the SARS-CoV E protein, a similar approach was performed, except using primers (CoE-37S2 and CoE-59AS4) to amplify the DNA fragment of SARS-CoV E protein a.a. 37–59. All the primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used for plasmid construction

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| HCV-1 | (5′-CGGAATTCAGGTCTCGTAGACCG-3′) |

| CC115-AS2 | (5′-CGCGGATCCCCTACGCCGGGGGTCTGT-3′) |

| CoE-11S | (5′-CGCGGATCCACGTTAATAGTTAATA-3′) |

| CoE-33AS3 | (5′-TGCTCTAGAGATGGCTAGTGTGACTAG-3′) |

| CoE-37S2 | (5′-CGCGGATCCCTTCGATTGTGTGCGT-3′) |

| CoE-59AS4 | (5′-TGCTCTAGAGTAGACGTAAACCGTTGG-3′) |

| CoE-11S | (5′-CGCGGATCCACGTTAATAGTTAATA-3′) |

| CoE-AS | (5′-CTAGTCTAGA TTAGACCAGAAGATCAGG-3′) |

| GEXE-S | (5′-CGCGGATCCATGTACTCATTCGTTTC-3′) |

| CoE-59AS | (5′-TGCTCTAGA TTAGTAGACGTAAACCGT-3′) |

| CoE 10/34-S | (5′-CGCGGATCCATGTACTCATTCGTTTCGGAAGAAACAGGTCTTACTGCGCTTC-3′) |

| CoE 36/60-AS | (5′-CAGATTTTTAACACGCGACGCAGTAAGGATGGC-3′) |

| CoE-75AS | (5′-CAGAAGATCAGGAACTCCTTCAGAAGAGTTCAGATTTTTAAC-3′) |

Note: GAATTC, TCTAGA, and GGATCC are the recognition sequences for EcoRI, XbaI, and BamHI, respectively, while nucleotides with bold fonts represent the stop codon (anti-sense of TAA)

In order to construct the plasmid expressing E protein without the first 10 amino acids and fused with a myc tag at the N-terminus, primers (CoE-11S and CoE-AS) were used in order to amplify the DNA fragment of E protein a.a. 11–76. After PCR, this DNA fragment was digested with BamHI/XbaI and cloned into expression vector pcDNA3-cMyc tag [20] linearized by BamHI/XbaI. In order to construct the plasmid expressing E protein without the last 17 amino acids fused with a myc tag at the N-terminus, a similar approach was performed except using primers (GEXE-S and CoE-59AS) to amplify the DNA fragment of SARS-CoV E protein a.a. 1–59. In order to construct the plasmid expressing E protein deleting amino acids 11–33 and fused with a myc tag at the N-terminus, a similar approach was performed except using primers (CoE 10/34-S and CoE-AS) in order to amplify the DNA fragment.

In order to construct the plasmid expressing E protein deleting amino acids 37–59 and fused with a myc tag at the N-terminus, primers (GEXE-S and CoE 36/60-AS) were used in order to amplify the DNA fragment of the first 65 amino acids of E protein without amino acids 37–59. After that, the PCR product was further amplified by the same sense primer (GEXE-S) and another antisense primer (CoE-75AS). After that, the PCR product was further amplified by the same sense primer and another antisense primer (CoE-AS). Then, this DNA fragment was digested with BamHI/XbaI and cloned into expression vector pcDNA3-cMyc tag linearized by BamHI/XbaI.

All the expression plasmids were verified by sequencing.

In vitro transcription/translation

The commercially available TnT system (Promega, USA) was used to perform in vitro transcription/translation assays. The experiments were conducted following the manufacturer’s instructions. About 2 μg of DNA was used in a 50-μl reaction volume. Microsomes were added to study glycosylation. To stop the translation, CaCl2 was added to the reaction mixture at a final concentration of 5 mM [12].

Protein expression in Vero E6 cells

The Vero E6 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 1% glutamine (200 mM, Biological Industries, USA), and 100 μg/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco BRL, USA). The cells were plated at the concentration of 2.5–2.7 × 105 cells/35-mm tissue culture dish. After an overnight incubation, cells were infected with a recombinant vaccinia virus carrying the T7 phage RNA polymerase gene [21]. Two hours after infection, cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of plasmid DNA using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen, Germany). Twenty-one hours after transfection, recombinant proteins in the cells were analyzed using immunoprecipitation assay or Western blotting analysis. The mRNAs, transcribed from either the CMV (cytomegalovirus) promoter or the T7 promoter in this expression system, used the same AUG start codon to initiate translation (in either pcDNA3.1/V5-His A or pcDNA3-myc expression vector).

Immunoprecipitation assay

The Vero E6 cells (1 × 106) were harvested 21 h after transfection and lysed in RIPA (radio-immunoprecipitation assay) buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% deoxychloic acid, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5). After full-speed centrifugation for 5 min in a microcentrifuge, the supernatant was incubated with mouse anti-V5 monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen) or mouse anti-myc monoclonal antibody (Oncogene, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight with shaking. The antigen–antibody complex was separated with pansorbin (Merck, Germany). The immunoprecipitated pellet was boiled for 10 min in sample buffer and then analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Western blotting. In each experiment, 10% of the cell lysates were used for expression analysis (by Western blotting assay directly) while 90% of the cell lysates were used for the co-immunoprecipitation assay.

Western blotting analysis

For Western blotting analysis, the cells were dissolved in sample preparation buffer after washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) twice. SARS-CoV M protein could not be detected with SDS-PAGE after regular boiling treatment [22]. Therefore, non-heated treatments were used in antigen preparations (sample buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 100 mM dithiothreitol, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol; no boiling) to detect the expression of SARS-CoV M protein [12]. After electrophoresis, the SDS-PAGE gel was transferred to a PVDF (polyvinylidene difluoride) membrane (Pall Corporation, USA). All the procedures were then carried out at room temperature according to the procedures described previously [23].

Confocal microscopy

About 2.5 × 105 cells were seeded into 35-mm culture dishes. After overnight incubation, the cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of plasmids using the Effectene transfection kit (Qiagen); 48 h after transfection, cells were fixed with acetone/methanol (1:1) at 0°C for 10 min. Fixed cells were washed twice with incubation buffer (0.05% NaN3, 0.02% saponin, 1% skim milk in PBS) for 5 min each time, then (Fig. 2) incubated with mouse anti-V5 monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen) at a concentration of 5 μg/ml at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were washed with PBS three times (5 min each time at room temperature), then incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G antibody at a final concentration of 25 μg/ml at 37°C for 30 min. Samples were washed with PBS three times (5–10 min each time at room temperature). Cells were co-transfected with the dsRED-ER plasmid (BECTON DICKENSEN, USA) when the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) needed to be localized. Experiments were repeated three times. To quantitate the average percentage of co-localization, similar to our previous reports [12, 13], Image J (NIH web) program was used. P values were calculated by t test. In Fig. 3, cells were stained with anti-V5 antibody (directly conjugated with FITC), mouse anti-myc monoclonal antibody, and then rhodamine ITC-conjugated anti-mouse antibody. DAPI (4′6-DIAMIDINO-2-PHENYLINDOLE HCl) (Merck) was used to stain the DNA for localization of the nucleus. Recombinant proteins encoded from expression vector pcDNA3.1/V5-His A contain a V5 tag fused to the C-terminus of the recombinant proteins.

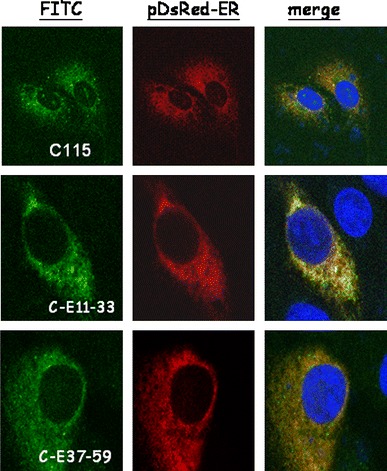

Fig. 2.

Subcellular localization of the recombinant fusion proteins C-E11-33-V5 and C-E37-59-V5. The dsRED-ER plasmid was used to define the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (red color), while DAPI was used to mark the localization of the nucleus (blue color). The recombinant fusion proteins, C115-V5, C-E11-33-V5, and C-E37-59-V5 were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibody (green color). The top panels are Vero cells co-transfected with dsRED-ER and C115-V5 plasmids, the middle panels are Vero cells co-transfected with dsRED-ER and C- E11-33-V5 plasmids and the lower panels are Vero cells co-transfected with dsRED-ER and C-E37-59-V5 plasmids. The orange color represents the localization of the fusion protein in the ER

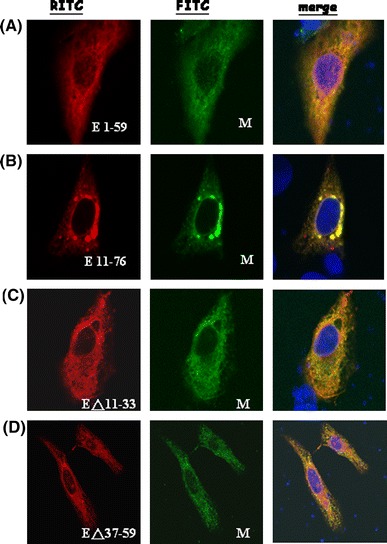

Fig. 3.

Co-localization of SARS-CoV M protein and the various E deletion mutants. Vero cells were co-transfected with M-V5 and myc-E1-59 (a), myc-E11-76 (b), EΔ11-33 (c), and EΔ37-59 (d) plasmids. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) stains for M protein while rhodamine ITC stains for the various E mutant proteins. Orange color (red color merged with green color) represents the co-localization of M protein and the various E deletion mutants

Results

Glycosylation of SARS-CoV E protein

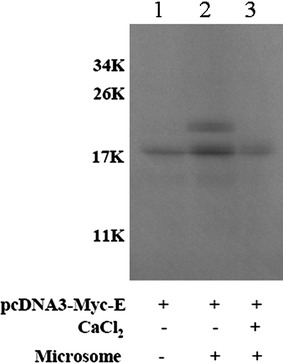

SARS-CoV E protein could be N-glycosylated at Asn 66 in mammalian cells [24]. Full-length SARS-CoV E gene fragment was cloned and expressed as a recombinant protein (76 a.a.) with an N-terminal myc tag (16 a.a.) in vitro translated in the reticulocyte lysate (Fig. 1). In the absence of microsomes (lane 1), an unglycosylated E protein (about 18 kDa), with the size larger than expected (92 a.a., about 10 kDa), was detected. An expected N-glycosylated E protein about 22 kDa (unglycosylated protein plus 4 kDa) was detected in the presence of microsomes (lane 2). Moreover, the N-glycosylated product was detected only when microsomes were added before, but not after, the translation reaction (lane 3). Thus, the glycosylation of SARS-CoV E protein occurs co-translationally.

Fig. 1.

SARS-CoV E protein was translated in vitro in reticulocyte lysate. Lane 1, only the plasmid expressing SARS-CoV E protein was added; Lane 2, microsomes and the plasmid expressing SARS-CoV E protein were added together in the lysate. Lane 3, after the translation of SARS-CoV E protein, CaCl2 was added to stop the translation reaction and then, the microsomes were added. After the reaction, the immunoprecipitation assay using anti-myc antibody was performed to remove hemoglobin protein before SDS-PAGE

Cytoplasmic protein insertion into the endoplasmic reticulum membrane

SARS-CoV E protein targets the ER membrane though it lacks of a conventional signal peptide [24]. There are two predicted transmembrane domains in the SARS-CoV E protein: a.a. 11–33 and a.a. 37–59 (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Both of these two transmembrane regions are predicted to be α-helices [25] (Supplemental Fig. 1A). In order to determine which transmembrane domain is responsible for the integration of SARS-CoV E protein into the ER, each of these two transmembrane domains (Supplemental Fig. 2) was linked with a cytoplasmic protein (a.a. 1–115 of hepatitis-C-virus core protein) and the fusion protein was expressed in Vero E6 cells. Co-localization of these recombinant proteins within the ER was demonstrated by confocal microscopy (Fig. 2). The average R values of pDsRed-ER + C115, pDsRed-ER + CE11-33, and pDsRed-ER + CM37-59 were 0.3379 ± 0.0723, 0.7537 ± 0.0535 (P = 0.0001), and 0.7926 ± 0.0406 (P = 0.0000002), respectively. Thus, either one of these two transmembrane regions could insert a cytoplasmic protein into the ER membrane efficiently.

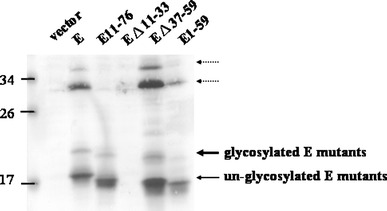

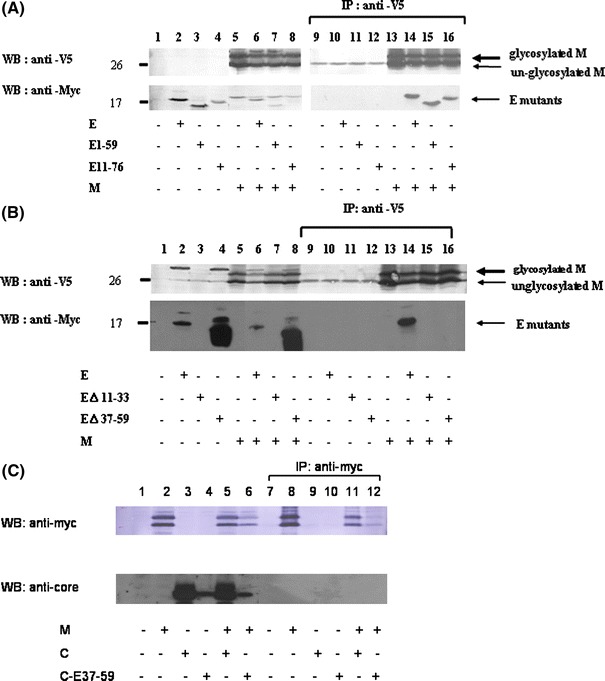

Both of the transmembrane domains of SARS-CoV E protein are required to interact with M protein

The interactions between SARS-CoV M and E proteins play an essential role in the viral particle assembly [19]. Multiple regions in the M protein are able to interact with E protein [13]. In order to determine which region/s of E protein is/are important for interaction with M protein, different regions of E protein were deleted individually (E11-76, EΔ11-33, EΔ37-59, E1-59). All the four E deletion mutants co-localized with M protein as demonstrated by confocal microscopy (Fig. 3). Similar to the results of in vitro translation (Fig. 1), the unglycosylated E protein was detected with mobility corresponding to about 18 kDa (Fig. 4). E protein without the first transmembrane domain (EΔ11-33) is a labile protein (Fig. 4), though it was detected by confocal microscopy in a limited number of cells (Fig. 3). Both of the E protein deletion mutants containing the two transmembrane domains (E11-76, E1-59) were pulled down by M protein using the co-immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 5a). However, E protein without the second transmembrane domain (EΔ37-59) was not pulled-down by M protein using co-immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 5b). Moreover, the second transmembrane domain of E protein alone was not pulled down by M protein using co-immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 5c). Thus, both of the transmembrane domains of SARS-CoV E protein are required to interact with M protein.

Fig. 4.

Expression of the various E deletion mutants in Vero cells. Cells were transfected with the expression vector (lane 1), myc-E (lane 2), myc-E11-76 (lane 3), EΔ11-33 (lane 4), EΔ37-59 (lane 5), and myc-E1-59 (lane 6) plasmid. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were lysed and the whole cellular proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-myc antibody. The unglycosylated E proteins are marked by a thin arrow, while the glycosylated ones are marked with a thick arrow. The two unidentified proteins (marked by dotted arrows) are larger than 30 kDa

Fig. 5.

Interactions between SARS-CoV M and the various E deletion mutants. a Vero E6 cells were transfected with the vector alone (lanes 1 and 9), the plasmid encoding myc-E (lanes 2 and 10), myc-E1-59 (lanes 3 and 11), myc-E11-76 (lanes 4 and 12), M-V5 (lanes 5 and 13), or co-transfected with the plasmids encoding myc-E and M-V5 (lanes 6 and 14), myc-E1-59 and M-V5 (lanes 7 and 15), myc-E11-76 and M-V5 (lanes 8 and 16). Cell lysates were directly analyzed by Western blotting (lanes 1–8) or immunoprecipitated with the anti-V5 antibody prior to Western blotting (lanes 9–16). b Vero E6 cells were transfected with the vector alone (lanes 1 and 9), the plasmid encoding myc-E (lanes 2 and 10), myc-EΔ11-33 (lanes 3 and 11), myc-EΔ37-59 (lanes 4 and 12), M-V5 (lanes 5 and 13), or co-transfected with the plasmids encoding myc-E and M-V5 (lanes 6 and 14), myc-EΔ11-33 and M-V5 (lanes 7 and 15), myc-EΔ37-59 and M-V5 (lanes 8 and 16). Cell lysates were directly analyzed by Western blotting (lanes 1–8) or immunoprecipitated with the anti-V5 antibody prior to Western blotting (lanes 9–16). c Vero E6 cells were transfected with the vector alone (lanes 1 and 7), the plasmid encoding myc-M (lanes 2 and 8), C115 (lanes 3 and 9), C-E37-59 (lanes 4 and 10), or co-transfected with the plasmids encoding myc-M and C115 (lanes 5 and 11), myc-M and C-E37-59 (lanes 6 and 12). Cell lysates were directly analyzed by Western blotting (lanes 1–6) or immunoprecipitated with the anti-myc antibody prior to Western blotting (lanes 7–12)

Discussion

In this study, the SARS-CoV E gene fragment was cloned and expressed as a recombinant protein fused with a myc tag at the N-terminus in vitro and in Vero E6 cells (Figs. 1, 4). The SARS-CoV E protein forms homodimers and homotrimers under nonreducing conditions in E. coli [17]. The transmembrane domain (a.a. 9–35) of SARS-CoV E protein forms SDS-resistant dimers, trimers, and pentamers [26]. The protein (about 18 kDa) that we detected was unglycosylated monomeric E protein with an unusual mobility on SDS-PAGE. This protein should not be a dimer since the glycosylated E protein is 4 kDa, but not 8 kDa larger than the unglycosylated form (Figs. 1, 4). Furthermore, the mobility of various E protein deletion mutants on the gel supports this argument (Fig. 4). Two unidentified protein bands (marked by dotted arrows in Fig. 4) greater than 30 kDa may not be the oligomeric form of this protein since they migrate similarly between the wild type and the deletion mutants of E protein (Fig. 4). These two bands are probably two unidentified cellular proteins interacting with E protein so extensively that they are resistant to treatments of SDS and boiling.

Similar to other N-glycosylated proteins [27], the glycosylation of SARS-CoV E protein occurred co-translationally but not post-translationally (Fig. 1). The E protein of SARS-CoV is a double-spanning membrane protein [24]. Which of these two hydrophobic domains in the SARS-CoV E protein contains the insertion and anchoring signals for ER-integration is not known. Both of these two transmembrane regions (a.a. 11–33 and 37–59) are predicted to be α-helices, which penetrate into the membrane by themselves (supplemental Fig. 1A). However, in another report, SARS-CoV E protein was predicted to have only one putative transmembrane α-helical hydrophobic domain (corresponding to the first transmembrane domain, a.a. 11–33, mentioned in our study) which is responsible for the membrane permeabilizing activity of this protein [16]. In order to determine which transmembrane domain is responsible for the integration of SARS-CoV E protein into the ER, each of these two transmembrane domains was linked with a.a. 1–115 of hepatitis C virus core protein which localizes in the cytoplasm [12]. Both of the single transmembrane regions were able to insert a cytoplasmic protein into the ER membrane (Fig. 2). These results suggest that either of the transmembrane regions is able to target SARS-CoV E protein into ER. Thus, there exists the second transmembrane region (a.a. 37–59) in the SARS-CoV E protein though this region is less hydrophobic than the first transmembrane region (a.a. 1–33) (supplemental Fig. 1B). Whether the second transmembrane region performs as the first one does in oligomer formation [26] and membrane permeabilization [16] needs further investigation. Figures 1 and 2 also imply that a nascent peptide of SARS-CoV E protein after the synthesis of the first or second transmembrane domains could integrate the peptide into the ER membrane, after which glycosylation occurs.

Results from the co-immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 5) showed that both the transmembrane domains of SARS-CoV E protein are required to interact with M protein, while either of the hydrophilic regions (a.a. 1–10 or a.a. 60–76) is dispensable. Thus, the interactions between SARS-CoV M and E proteins reside mainly in the E.R. membrane, which is supported by our previous study using M deletion mutants [13].

In summary, the N-glycosylation of SARS-CoV E protein is a co-translational event. Either of the two transmembrane regions in the E protein is able to insert a cytoplasmic protein into the ER membrane. Both of the transmembrane regions of E protein are required to interact with M protein. These findings are important for better understanding of SARS-CoV assembly and developing VLP vaccines for SARS-CoV.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

The predicted topology (a) and hydropathy profile (b) of SARS-CoV E protein. Program at (http://bp.nuap.nagoya-u.ac.jp/sosui/) was used to do the prediction. (TIFF 382 kb)

The various constructs to link the hydrophobic domains of SARS-CoV E protein with a.a. 1–115 of hepatitis C virus core protein. (TIFF 102 kb)

The construction of various SARS-CoV E protein deletion mutants.(TIFF 135 kb)

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants (TCIRP96004-02, TCIRP95002-01, and TCIRP96004-05) from Tzu Chi University to Drs. Hui-Chun Li and Shih-Yen Lo, and grant (NSC 96-3112-B-320-001) from the National Science Council of Taiwan to Dr. Shih-Yen Lo.

References

- 1.Poon LL, Guan Y, Nicholls JM, Yuen KY, Peiris JS. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004;4:663. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01172-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donnelly CA, et al. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004;4:672. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01173-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enserink M. Science. 2003;300:1351. doi: 10.1126/science.300.5624.1351a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes KV, Enjuanes L. Science. 2003;300:1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai M. J. Biomed. Sci. 2003;10:664. doi: 10.1007/BF02256318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satija N, Lal SK. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1102:26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1408.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen VP, Hogue BG. J. Virol. 1997;71:9278. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9278-9284.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen VP, Hogue BG. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998;440:361. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5331-1_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vennema H, Godeke GJ, Rossen JW, Voorhout WF, Horzinek MC, Opstelten DJ, Rottier PJ. EMBO J. 1996;15:2020. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho Y, Lin PH, Liu CY, Lee SP, Chao YC. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;318:833. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nal B, et al. J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:1423. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80671-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma HC, et al. J. Biomed. Sci. 2008;15:301. doi: 10.1007/s11373-008-9235-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh YC, Li HC, Chen SC, Lo SY. J. Biomed. Sci. 2008;15:707. doi: 10.1007/s11373-008-9278-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu DX, Yuan Q, Liao Y. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:2043. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7103-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, et al. Biochem. J. 2005;392:135. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torres J, et al. Biophys. J. 2006;91:938. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao Y, Lescar J, Tam JP, Liu DX. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;325:374. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson L, McKinlay C, Gage P, Ewart G. Virology. 2004;330:322. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Y. L. Siu et al., J Virol, (Aug 27, 2008)

- 20.Ma HC, Ku YY, Hsieh YC, Lo SY. J. Biomed. Sci. 2007;14:31. doi: 10.1007/s11373-006-9127-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuerst TR, Niles EG, Studier FW, Moss B. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:8122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YN, et al. J. Virol. Methods. 2005;129:152. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma HC, et al. J. Biomed. Sci. 2008;15:417. doi: 10.1007/s11373-008-9248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan Q, Liao Y, Torres J, Tam JP, Liu DX. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3192. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirokawa T, Boon-Chieng S, Mitaku S. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:378. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torres J, Wang J, Parthasarathy K, Liu DX. Biophys. J. 2005;88:1283. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewin B. GENES VIII. Chapter 27: Protein Trafficking. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2004. pp. 788–789. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The predicted topology (a) and hydropathy profile (b) of SARS-CoV E protein. Program at (http://bp.nuap.nagoya-u.ac.jp/sosui/) was used to do the prediction. (TIFF 382 kb)

The various constructs to link the hydrophobic domains of SARS-CoV E protein with a.a. 1–115 of hepatitis C virus core protein. (TIFF 102 kb)

The construction of various SARS-CoV E protein deletion mutants.(TIFF 135 kb)