Abstract

Recombination between infectious bronchitis viruses (IBVs), together with point mutations, insertions, and deletions, is thought to be responsible for the emergence of new IBV variants. SAIBK2 is a nephropathogenic strain isolated from layer flocks vaccinated with live attenuated H120 vaccine in Sichuan province, China in 2011. SAIBK2 causes severe kidney lesions and results in 50 % mortality in 30-day-old specific-pathogen-free chickens (with a dose of 105 EID50/0.1 mL SAIBK2 per chicken). The complete genome of SAIBK2 consists of 27669 nucleotides, excluding the poly-A tail at the 3′ end. SAIBK2 has the highest identity to YX10 in terms of complete genome. Phylogenetic analysis of complete sequence showed that SAIBK2 belongs to the most dominant genotype in China. Comparison and recombination analyses with other IBV strains revealed that SAIBK2 may originate from recombination events among a YX10-, a YN-, and a Mass-like strain. Furthermore, whole gene 5 and parts of nsp 3, nsp 4, nsp 16, and N genes are involved in the recombination events, and the uptake of these regions from YN and Mass strains by SAIBK2 may increase its replication efficiency and be responsible for its increased virulence in specific-pathogen-free chickens.

Keywords: Infectious bronchitis virus, Complete genome, Virulent strain, Recombination event

Introduction

Avian infectious bronchitis (IB) is a common, highly contagious, and acute disease of chickens; its pathogen infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) is a member of Gamma-coronavirus of Coronaviridae family. IBV can cause pathological lesions in different organs varying from respiratory tract to kidney and gonads, resulting in heavy economic losses.

IBV is an enveloped, non-segmented, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus, with a genome approximate 27.6 kb in length. In the genome, two-thirds of the 5′ region encodes two polyproteins, polyprotein 1a (pp 1a) and polyprotein 1ab (pp 1ab), in which pp 1ab is an extension of pp 1a by a minus 1 frameshift translation mechanism [1]. These two polyproteins are post-translationally processed into fifteen non-structural proteins (nsp 2–16, IBV does not have nsp 1 that is found in some other coronaviruses). The processing of pp 1a/1ab is performed by two virus-encoded proteases: papain-like protease (PLpro) contained in the nsp 3 and main protease (Mpro) contained in the nsp 5 [2]. Then these fifteen mature non-structural proteins take part in the process of viral RNA replication and other aspects of viral pathogenesis. Recently, some researches in reverse genetics had found that these nsps may play vital roles in pathogenesis [3, 4]. The remaining one-third of IBV genome encodes four structural proteins: spike glycoprotein (S), small membrane protein (E), membrane glycoprotein (M), phosphorylated nucleocapsid protein (N), and four accessory proteins: 3a, 3b, 5a, and 5b. The S glycoprotein has been demonstrated to be the determinant of cell tropism [5], and the S1 subunit of S glycoprotein can induce neutralizing and serotype-specific antibodies [6, 7]. The M and E proteins are two membrane-binding proteins. The N protein has the activity to bind viral RNA forming ribonucleoprotein (RNP). All these four structural proteins together with the viral RNA constitute the enveloped virion. The four accessory proteins have been demonstrated to be dispensable for virus replication; their actual functions are still undefined [8, 9].

IBV was firstly detected in the USA as the Massachusetts (Mass)-type in early 1940s. To date, numerous IBV strains have been defined worldwide. IBV has high mutation frequency. Point mutations, insertions, deletions, and recombination are of common occurrence in the IBV genome, which are responsible for the emergence of new IBV strains [10–14]. In this present study, a novel virulent strain was isolated and designated as SAIBK2 (abbreviation of Sichuan Avian Infectious Bronchitis Kidney 2). To investigate the origin of SAIBK2 and the reason for its increased virulence, the complete genome was sequenced and the complete sequence analyses were performed. The results revealed that SAIBK2 originated from multiple recombination events among a YN-, a YX10-, and a Mass-like strains and these recombination events may account for its increased virulence.

Materials and methods

Virus isolation and amplification

Throughout 2011, 435 layer chickens suspected to be infected with IBV were collected from 15 chicken farms from 8 areas in Sichuan province, China. All these flocks were vaccinated with live attenuated H120 vaccine. 53 of the 435 chickens were confirmed to be infected with IBV. Of the 53 disease chickens, 12 were infected by a novel virulence IBV strain which was designated as SAIBK2. 12 tissue samples of swollen kidneys from diseased chickens, infected with SAIBK2, were prepared as 10 % w/v tissue suspensions in 0.1 % phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then the tissue suspensions were clarified by centrifugation at 1500 g at 4 °C for 10 min, and filtered by 0.22-μm membrane filters. The supernatant was inoculated into the allantoic cavity of 10-day-old embryonated specific-pathogen-free (SPF) eggs. The embryos were incubated at 37 °C and examined twice daily for their viability. The allantoic fluid was collected at 72 h post-inoculation and stored at −80 °C.

Pathogenicity studies

Twenty-one-day-old SPF chicks were used for assessing the pathogenicity of SAIBK2, ten in experiment group and ten in control group, and kept in two isolators with negative pressure. The experiment group was inoculated by oculonasal administration at one-day old with a dose of 105 EID50/0.1 mL SAIBK2 per chick, and chicks of the control group were mock-inoculated with 0.1 mL sterile allantoic fluid. All chicks were observed daily for signs of disease and death for 30 days after infection. Dead chicks were dissected for the observations of organs.

Viral RNA extraction, RACE, and RT-PCR

Primers were designed on the base of IBV complete genome sequences from GenBank (Table 1). 5 primers were used for RACE PCR to amplify 5′ and 3′ terminal sequences, and 17 pairs of primers were used to amplify the remaining parts of SAIBK2 genome (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sequences used in this study

| Strains | GenBank accession no. | Strains | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| California_99a,b | AY514485.1 | CK/CH/LSD/05Ia | EU637854.1 |

| Arkansas_DPIa,b | GQ504720.1 | ck/CH/LHLJ/140906a | KP036502.1 |

| ck/CH/LJL/111054a,c | KC506155.1 | Connecticut_vaccinea,b | KF696629.1 |

| Delaware_072a,b | GU393332.1 | IBVUkr27-11a | KJ135013.1 |

| Georgia_1998a,b | GQ504722.1 | 4/91_vaccinea,b | KF377577.1 |

| H120a,b,c | FJ888351.1 | YNa,b,c | JF893452.1 |

| ck/CH/LHB/121040a | KJ425495.1 | ck/CH/LDL/97Ia | JX195177.1 |

| H52a,b | EU817497.1 | ck/CH/LHB/100801a | JF330898.1 |

| Peafowl/GD/KQ6/2003a | AY641576.1 | JMKa | GU393338.1 |

| M41a | DQ834384.1 | Holtea,b | GU393336.1 |

| ck/CH/LHLJ/100902a | JF828980.1 | Graya,b | GU393334.1 |

| CK/CH/XDC-_2/2013a | KM213963.1 | BJa | AY319651.1 |

| SDZB0808a | KF853202.1 | CQ04-1a | HM245924.1 |

| Beaudetteb | AJ311317.1 | DY07a | HM245923.1 |

| SDIB821/2012a | KF574761.1 | ITA/90254/2005a | FN430414.1 |

| GX-NN09032a | JX897900.1 | A2a | EU526388.1 |

| YX10a,b,c | JX840411.1 | SAIBKa,b | DQ288927.1 |

| GX-YL9a | HQ850618.1 | Mass41_1985b | FJ904723.1 |

| Sczy3a | JF732903.1 | ck/ZA/3665/11a | KP662631.1 |

| CK/SWE/0658946/10a | JQ088078.1 | Mass41_2006b,c | FJ904713.1 |

| TW2575/98a | DQ646405.2 | HKU11-934d | FJ376619.2 |

| SC021202a | EU714029.1 | HKU13-3514e | NC_011550.1 |

aIBV sequences involved in phylogenetic analysis

bIBV sequences involved in sequence identity analysis

cIBV sequences involved in recombination analysis

dBulbul coronavirus sequence

eMunia coronavirus sequence

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primers | Location | Forward primer (5′–3′) | Reverse primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 218-1526 | CATCCGTTGCTTGGGCTACCTAG | GCAGACCAACCTTCTGGTTCC |

| 2 | 1439-3082 | CACAAGTTGTTGTTCGTGGC | GAGCGTCCTTATGAACTATAC |

| 3 | 2545-3801 | GCGGGTGGCAAGACTGTCAC | AATGCCTTTGACATAAGAAGG |

| 4 | 3738-5606 | GGACTATGTTAAGAAACATGG | CCATCTCCTACTTTATCGGC |

| 5 | 5434-7340 | GTTGATGGTGTAACTATGGGC | GTACCACTAACGATACCACC |

| 6 | 7219-9220 | TCAGCGACTGTCAAGTCAGG | TACCACCATAAGAGCAAGC |

| 7 | 9171-10949 | GAAAGCAAATTGTGGTGATAG | GAGGGAATGTGTGAAAACTC |

| 8 | 10815-12586 | GGACAATTTGTTGGGTATGC | GTTCATAATTACTAGGAGTGG |

| 9 | 12412-14028 | CCTGATGTTGTAGAGCGAGCC | AAGAATGGACACACCTGCCAC |

| 10 | 13780-15652 | TTTGAATGTTATGAAGGTGG | TAGTCTTACCAGGTTCCCACG |

| 11 | 15520-16868 | TCATTAAGACGCTTTGCTG | ATGACTACAAGTATACCACGC |

| 12 | 16738-19004 | GTAGACTCTTCACAAGGTTC | TAAACATACAGATTCGCTCC |

| 13 | 18402-20306 | GGCTTCTTATAATGCAGCTG | AAATTCACAACTGGTGTTGC |

| 14 | 20070-22284 | CAAGATTGTGCATGGTGGAC | TATGTTATCACAAACAGGACC |

| 15 | 21262-22963 | ACACAAACAGCTCAGAGTGG | CTTGAATTGCATCAAGTTGC |

| 16 | 22788-24887 | CATTGGTCATATGCAGGAAGG | GGAGTATTGAACCTACGGCATTA |

| 17 | 24627-27112 | TGGATACGCAACTAGGAGTCG | CATCATCAAATTCCAGCTGTGC |

| 5′ regiona | 1-449 | CATGGCTACATGCTGACAGCCTA | TACAAACGTCGTATAGCCGACC |

| 3′ regionb | 26942-27669 | GTAAGACCAAAATCACGCCCAAG | AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT |

| 3′ RTc | poly-A | AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGTAC(T)30 |

aPCR Primers used in 5′ RACE

bPCR Primers used in 3′ RACE

cRT Primer used in 5′ RACE

Viral RNA was extracted from virus-infected allantoic fluid with TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and reverse transcription were performed using 3′/5′ RACE kit (TaKaRa, Japan) and SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

PCR was conducted with 2 μL cDNA as template in a total of 25 μL reaction volume containing 2.5 μL of 10 × LA buffer, 5 μL of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 2 μL of 25 mM MgCl2, 10 pmol of each primer, and 0.3 μL of LA Taq polymerase (TaKaRa, Japan). The PCR parameters included an initial denaturation for 5 min at 94 °C followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 50 s, annealing at 53 °C for 50 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1–3 min depending on the sizes of the products and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

Cloning and sequencing of the genome sequence

17 overlapped PCR fragments spanning the entire genome, 5′ and 3′ terminal sequences (19 fragments altogether) were purified from 0.8 % agarose gel with QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, CA). The purified products were cloned into the pMD19-T Vector (TaKaRa, Japan). Nucleotide sequences of each fragment were determined by consensus sequence of three, at least, positive clones. The nucleotide sequences of the positive clones were determined by Sangon Biological Engineering Technology and Services Co., Ltd. Sequences were assembled into complete genome sequence using SeqMan II program of DNAstar software package (DNAStar, Madison, WI).

Genome sequence comparison, phylogenetic, and recombination analysis

42 IBV sequences and 2 bird coronavirus strains (as outgroup) downloaded from GenBank were used in this study. Sequence comparisons and nucleotide identities of complete or partial genome were computed using MegAlign clustal V method. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MEGA version 6 with the neighbor-joining method. The bootstrap values were determined from 1000 replicates of the original data. The IBV sequences were used in this study and their accession numbers are listed in Table 1.

To identify recombination events, complete genomic sequence of SAIBK2 were compared with those of YX10, YN, and three Mass-type strains (H120, Mass41 2006, and ck/CHLJL/111054), and the results were used for Similarity Plotting analysis using the SimPlot program version 3.5.1 with a window size of 200 bp and a step size of 20 bp. Pairwise comparisons between SAIBK2 and those above-mentioned five viruses were performed to confirm the precise recombination breakpoints. Phylogenetic trees based on every recombinant fragments were constructed to avoid phylogenetic biases derived from ignoring recombination events.

Results

Pathogenicity studies

Obvious clinical signs were observed in all SAIBK2-infected chicks from 3–19 days postinfection (dpi), including ruffled feathers and huddled together. Five of the ten chicks died: one on 4 dpi, two on 6 dpi, and two on 7 dpi, in the SAIBK2-infected group. Gross lesions in the dead chicks were confined mainly to the kidneys. No overt disease was observed and none of the chicks died in control group.

Genome organization of isolate SAIBK2

To obtain the genome sequence of SAIBK2 strain, 17 overlapping large fragments, ranging from 1309 to 2486 bp, were sequenced and assembled using DNAstar software.

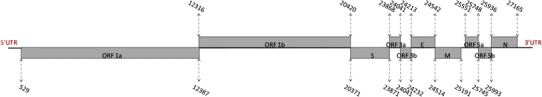

The complete genome sequence of SAIBK2 obtained in this study was submitted to Genbank database under the accession number of KU317090. The complete genome of SAIBK2 strain consists of 27669 nt, excluding the poly-A tail at the 3′ end, which encodes 6 genes. Gene 1 has a length of 19892 nt, consisting of 2 overlapping ORFs, ORF1a, and ORF1b which are separately 11859 and 8105 nt in length. There are 50 nt overlap between Gene 1 and Gene 2. Gene 2 with a length of 3501 nt has a single ORF, encoding S glycoprotein which is cleavaged into 2 subunits S1 and S2 with 1620 and 1881 nt in length, respectively (encoding 540 and 626 aa). Between Gene 2 and Gene 3, there are 4 nt overlap. Gene 3 has 675 nt consisting of 3 overlapping ORFs, encoding 2 accessory proteins (3a and 3b), and structural protein E with 174, 192, and 330 nt in length, respectively (encoding 57, 62, and 109 aa). Between 3a and 3b, 3b and E, there are 1 and 20 nt overlap, respectively. There are 29 nt overlap between Gene 3 and Gene 4. Gene 4 contains 678 nt, encoding M protein of 225 aa. A 361 nt non-encoding region is detected between Gene 4 and Gene 5. Gene 5 containing 443 nt consists of 2 overlapping ORFs, ORF5a and ORF5b, which are 198 and 249 nt in length, respectively (encoding 65 and 82 aa). There are 58 nt overlap between Gene 5 and Gene 6. Gene 6, encoding N protein, contains 1230 nt (encoding 409 aa). Untranslated regions (UTRs) at 5′-end and 3′ end of the genome are 528 and 505 nt in length, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Expression of ten ORFs of the SAIBK2 genome. The gray boxes represent ORFs, and the numbers above or under them show the positions in SAIBK2 genome

Genome sequence analyses

Genome sequence comparison

BLAST searches with the complete genome sequence of SAIBK2 showed that it is most similar to that of YX10, sharing 96.1 % nucleotide identity. Compared with YX10, there are a 3-nt insertion at 341-343 nt, a 3-nt deletion at 3269-3298 nt, and a 4-nt deletion at 25554-25557 nt in SAIBK2 genome. To further evaluate the nucleotide sequence identities between isolate SAIBK2 and other IBV strains, sequence alignments between the complete or partial genomic sequences of SAIBK2 and 16 IBV strains from GenBank (Table 1) were performed. As shown in Table 3, SAIBK2 shows the highest similarity with YX10 in most regions (nsp 2, nsp 5–10, nsp 12–15, Gene 2, Gene 3, and Gene 4). Nsp 3, nsp 4, nsp 11, and nsp 16 of SAIBK2 were most similar to those of YN. ORF5a of SAIBK2 is completely the same as that of Gray, Connecticut vaccine, Mass41_2006, California_99, and Arkansas_DPI. ORF5b of SAIBK2 is completely the same as that of Connecticut vaccine and Georgia_1998_Vaccine. Gene 6 of SAIBK2 is most similar to that of Connecticut vaccine and Mass41_2006.

Table 3.

Percentage of sequence identities of different regions of SAIBK2 compared with other IBV strains

| Strain | Complete genome | Gene 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene 1 | Nsp2 | Nsp3 | Nsp4 | Nsp5 | Nsp6 | Nsp7 | ||

| Beaudette | 86.7 | 87.3 | 85.2 | 85.8 | 85.6 | 86.8 | 85.8 | 92.4 |

| Gray | 87.0 | 87.5 | 84.3 | 86.1 | 87.5 | 87.2 | 85.9 | 92.0 |

| Holte | 85.7 | 87.6 | 86.0 | 85.9 | 86.4 | 86.6 | 85.4 | 92.4 |

| YN | 90.8 | 91.9 | 92.8 | 93.9 | 92.5 | 85.3 | 86.7 | 94.4 |

| Mass41_1985 | 86.5 | 87.3 | 84.9 | 86.0 | 85.2 | 87.8 | 84.8 | 92.0 |

| 4/91_vaccine | 86.3 | 86.7 | 85.3 | 84.3 | 86.0 | 85.6 | 84.0 | 92.4 |

| Connecticut_vaccine | 87.1 | 87.3 | 84.5 | 85.6 | 86.2 | 86.9 | 85.3 | 92.4 |

| Mass41_2006 | 87.2 | 87.3 | 84.3 | 85.6 | 86.7 | 86.9 | 85.3 | 92.4 |

| California_99 | 86.9 | 87.2 | 85.4 | 85.2 | 87.0 | 86.2 | 85.1 | 92.0 |

| Arkansas_DPI | 87.1 | 87.4 | 85.3 | 85.1 | 86.8 | 86.9 | 86.1 | 92.0 |

| Delaware | 84.6 | 86.8 | 85.5 | 84.1 | 86.8 | 85.6 | 84.2 | 92.4 |

| Georgia_1998_Vaccine | 85.0 | 87.2 | 85.0 | 85.4 | 86.7 | 83.4 | 85.9 | 92.0 |

| H52 | 86.4 | 87.0 | 85.5 | 84.6 | 86.9 | 85.6 | 84.5 | 92.0 |

| H120 | 86.5 | 87.1 | 85.3 | 84.7 | 86.6 | 85.6 | 84.2 | 92.0 |

| YX10 | 96.1 | 96.1 | 97.2 | 93.6 | 91.8 | 99.7 | 98.2 | 96.8 |

| SAIBK | 89.1 | 90.2 | 93.0 | 92.7 | 86.5 | 86.6 | 86.4 | 92.0 |

| Strain | Gene 1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nsp8 | Nsp9 | Nsp10 | Nsp11 | Nsp12 | Nsp13 | Nsp14 | Nsp15 | Nsp16 | |

| Beaudette | 86.5 | 89.5 | 90.8 | 90.9 | 88.7 | 89.6 | 91.6 | 86.7 | 85.8 |

| Gray | 87.8 | 88.9 | 90.1 | 92.4 | 88.8 | 89.4 | 91.2 | 87.8 | 86.6 |

| Holte | 88.3 | 87.4 | 89.4 | 92.4 | 89.6 | 89.6 | 90.3 | 87.3 | 88.6 |

| YN | 87.6 | 91.3 | 91.5 | 97.0 | 95.3 | 89.9 | 89.1 | 88.8 | 94.7 |

| Mass41_1985 | 87.0 | 88.9 | 90.1 | 95.5 | 89.7 | 89.3 | 90.4 | 86.5 | 86.2 |

| 4/91_vaccine | 87.1 | 88.6 | 90.1 | 89.4 | 89.2 | 89.3 | 88.8 | 86.2 | 86.7 |

| Connecticut_vaccine | 88.1 | 89.8 | 88.7 | 93.9 | 89.3 | 89.9 | 90.4 | 87.6 | 85.8 |

| Mass41_2006 | 87.0 | 89.2 | 91.3 | 92.4 | 89.1 | 89.8 | 90.0 | 88.1 | 86.6 |

| California_99 | 87.6 | 88.3 | 88.3 | 93.9 | 89.3 | 89.6 | 90.2 | 87.4 | 85.3 |

| Arkansas_DPI | 88.1 | 89.8 | 89.9 | 92.4 | 88.8 | 89.9 | 90.3 | 87.5 | 88.2 |

| Delaware | 87.1 | 88.3 | 91.3 | 89.4 | 89.1 | 88.8 | 89.3 | 87.2 | 86.8 |

| Georgia_1998_Vaccine | 87.8 | 89.8 | 91.3 | 93.9 | 88.9 | 89.5 | 90.5 | 87.6 | 85.9 |

| H52 | 86.7 | 88.6 | 90.1 | 95.5 | 89.7 | 89.2 | 90.2 | 86.6 | 86.4 |

| H120 | 87.3 | 89.5 | 91.5 | 89.4 | 89.1 | 89.6 | 90.2 | 88.0 | 86.6 |

| YX10 | 94.9 | 97.3 | 98.6 | 95.5 | 97.7 | 98.0 | 99.0 | 97.1 | 93.7 |

| SAIBK | 86.7 | 88.9 | 90.8 | 89.4 | 89.4 | 89.9 | 88.8 | 88.7 | 93.1 |

| Strain | Gene 2 | Gene 3 | Gene 4 | Gene 5 | Gene 6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | 3a | 3b | E | M | 5a | 5b | N | |

| Beaudette | 77.4 | 85.4 | 83.3 | 76.9 | 87.9 | 90.1 | 92.9 | 97.6 | 89.1 |

| Gray | 75.3 | 86.6 | 85.6 | 74.9 | 86.1 | 89.2 | 100.0 | 98.0 | 89.5 |

| Holte | 76.1 | 86.0 | 79.9 | 74.4 | 87.9 | 88.2 | 93.4 | 95.2 | 89.0 |

| YN | 79.8 | 93.2 | 93.1 | 75.9 | 87.6 | 91.3 | 83.8 | 96.0 | 87.6 |

| Mass41_1985 | 77.4 | 85.8 | 83.3 | 77.4 | 88.2 | 90.1 | 89.9 | 97.2 | 90.4 |

| 4/91_vaccine | 78.1 | 85.1 | 84.5 | 72.3 | 81.2 | 90.6 | 89.9 | 97.2 | 88.5 |

| Connecticut vaccine | 76.6 | 86.4 | 82.2 | 73.3 | 86.1 | 90.9 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 90.9 |

| Mass41_2006 | 77.4 | 86.1 | 82.2 | 73.3 | 85.8 | 91.0 | 100.0 | 99.2 | 90.9 |

| California_99 | 75.5 | 85.4 | 82.2 | 73.3 | 88.8 | 91.6 | 100.0 | 98.8 | 89.9 |

| Arkansas_DPI | 75.6 | 86.4 | 86.2 | 73.8 | 85.8 | 90.7 | 100.0 | 99.6 | 90.7 |

| Delaware | 57.9 | 75.0 | 82.2 | 73.3 | 87.0 | 89.4 | 98.0 | 99.2 | 89.5 |

| Georgia_1998_Vaccine | 58.6 | 74.8 | 82.8 | 74.4 | 88.8 | 90.4 | 99.5 | 100.0 | 90.8 |

| H52 | 77.7 | 85.4 | 82.8 | 77.4 | 87.6 | 90.3 | 93.9 | 96.8 | 88.7 |

| H120 | 77.4 | 85.6 | 83.3 | 77.4 | 86.7 | 90.0 | 94.4 | 97.2 | 88.3 |

| YX10 | 98.7 | 98.0 | 99.4 | 93.8 | 97.3 | 97.5 | 83.8 | 92.8 | 90.1 |

| SAIBK | 80.3 | 93.1 | 91.4 | 76.9 | 86.7 | 90.1 | 84.3 | 96.4 | 88.2 |

The highest nucleotide identities of different regions are indicated in bold values

Phylogenetic analysis

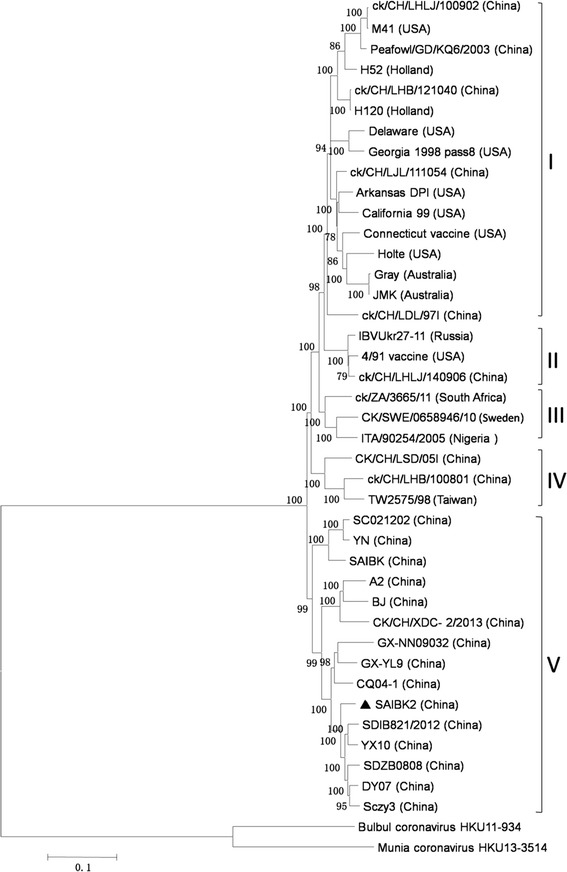

In order to study the genetic relatedness between SAIBK2 and other IBV strains, the sequence of SAIBK2 was compared with complete genomic sequences of 39 IBV and 2 bird coronavirus from GenBank (Table 1) to construct phylogenetic tree. Based on the Phylogenetic tree, we grouped IBV strains into 5 clades (Fig. 1). Group I was constituted by Mass-genotype strains. Group II was 4/91 genotype. The third group is constituted of two Africa strains and one Europe strain. The fourth group was formed by two China strains and one Taiwan strain. Isolate SAIBK2 was clustered into group V, which was exclusively formed by China strains. This result revealed that SAIBK2 belongs to the most predominant genotype in China (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree by neighbor-joining method (bootstrapping for 1000 replicates with its value >70 %) based on complete genome. Sequence of SAIBK2 was labeled by filled triangle

Recombination analysis

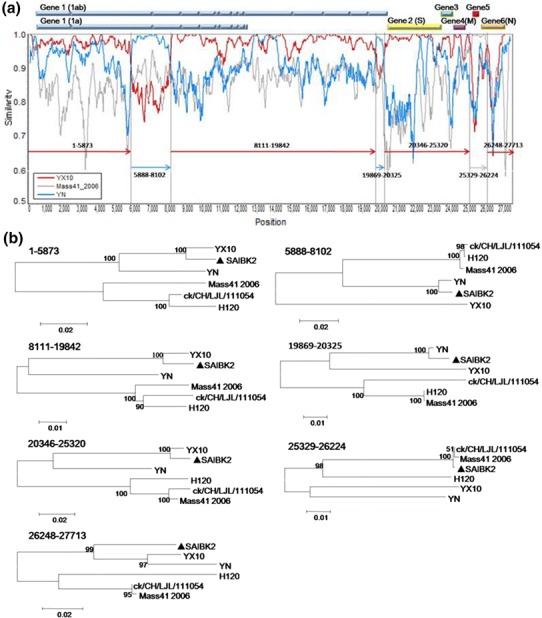

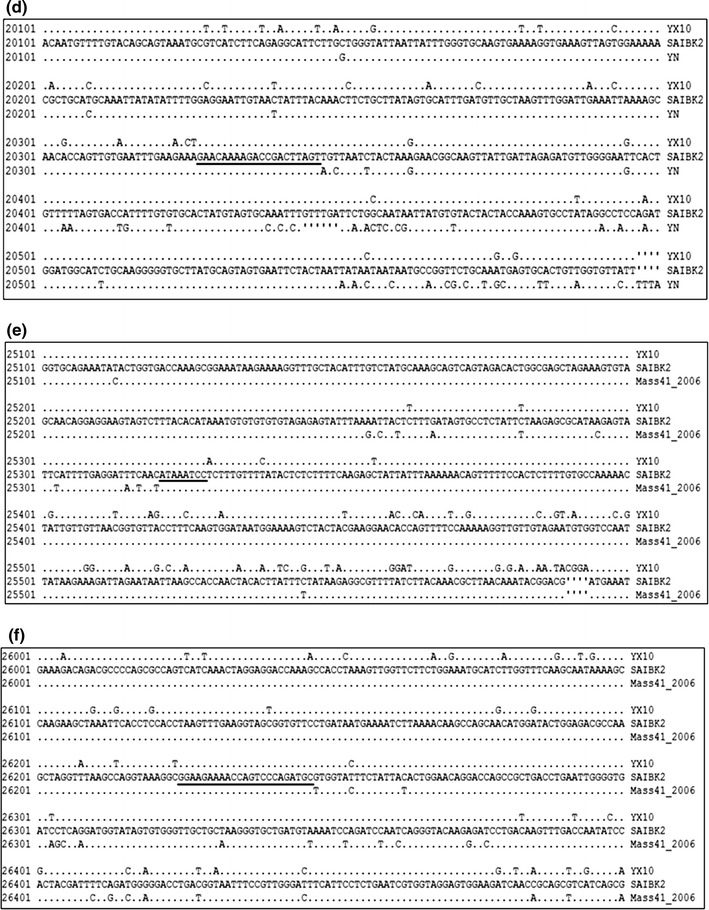

To detect possible recombination events within SAIBK2 genomic sequence, SimPlot analysis was used to show the consecutive nucleotide identity between SAIBK2 and other IBV complete sequences from GenBank. The results indicated that SAIBK2 may be a mosaic formed by a YX10-, a YN-, and a Mass-like strain (Fig. 3). To find out the regions where the template switches (breakpoint) have taken place, pairwise comparison between the complete genomic sequences of SAIBK2, YX10, YN, and Mass41_2006 was performed, and six breakpoints were found as shown in Fig. 4. The first recombination breakpoint is located in the nsp 3 (5874-5887 nt), the second is located in the nsp 4 (8103-8116), the third and fourth breakpoints are located in nsp 16 (19843-19868 and 20326-20345 nt, respectively), the fifth breakpoint is located in the non-coding region between ORF4 and ORF5 (25321-25328 nt), the last is located in N gene (26225-26247 nt). These results revealed that the YX10-like strain is the major parent of SAIBK2 and the first two recombinant regions (5888-8102 and 19869-20325 nt) are from the YN-like strain, the third region (25329-26224 nt) is from the Mass-like strain. To further verify these three above-mentioned recombinant events, the sequence identity (Table 4) and phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 3b) among corresponding regions of SAIBK2, YN, YX10, and three Mass-like strains were performed. The results showed that SAIBK2 has higher similarity with YX10 than YN and Mass-like viruses in the regions of 1-5873, 8111-19842, 20346-25320, and 26248-27713 nt. In contrast, SAIBK2 is more similar to YN than YX10 and Mass-type strains in the regions of 5888-8102 and 19869-20325 nt, and is more similar to Mass-like strains in the region of 25329-26224 nt (Table 4). In line with the results obtained from the Simplot analysis and identity analysis (Table 4), phylogenetic trees constructed using the corresponding gene fragments also showed the same results (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Recombination analysis of isolate SAIBK2. SimPlot analysis was performed using SAIBK2 as the query sequence (a). Bars at the top represent relative positions of Genes of IBV. The dummy lines show the deduced breakpoints. The arrows show different regions and their colors are the same as those of the parent viruses. The numbers above those arrows show corresponding nucleotide positions in the alignment. The y axis shows the percentage similarity within a sliding window of 200 bp centered on the position plotted, with a step size between plots of 20 bp. Phylogenetic trees of genome positions 1-5873, 5888-8102, 8111-19842, 19869-20325, 20346-25320, 25329-26224, and 26248-27713 among SAIBK2, YX10, YN, and three Mass-type viruses (H120, ck/CH/LJL/111054, and Mass41_2006) (b). Phylogenetic trees were constructed by neighbor-joining method (bootstrapping for 1000 replicates). Sequence of SAIBK2 was labeled by filled triangle

Fig. 4.

Analysis of breakpoint. a–d are breakpoint analysis between SAIBK2, YX10, and YN. e, f are breakpoint analysis between SAIBK2, YX10, and Mass41 2006. Numbers in the left show the nucleotide position in the alignment. Only the nucleotides which differ from those of SAIBK2 are listed. The breakpoints are underlined. The deleted nucleotides are indicated by prime

Table 4.

Percentage of sequence identity of corresponding regions as indicated among SAIBK2, YX10, YN, and three Mass-type viruses (H120, ck/CH/LJL/111054, and Mass41_2006)

| Virus | Position in alignment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-5873 | 5888-8102 | 8111-19842 | 19869-20325 | 20346-25320 | 25329-26224 | 26248-27713 | |

| YX10 | 97.5 | 84.2 | 98.0 | 89.9 | 98.1 | 86.8 | 93.2 |

| YN | 92.0 | 98.6 | 90.3 | 98.9 | 87.2 | 86.3 | 90.1 |

| H120 | 84.6 | 88.7 | 88.4 | 88.0 | 83.1 | 90.4 | 83.8 |

| ck/CH/LJL/111054 | 85.5 | 88.6 | 88.5 | 86.7 | 83.0 | 99.9 | 86.6 |

| Mass41_2006 | 85.0 | 88.8 | 88.6 | 88.0 | 83.3 | 99.7 | 87.7 |

These results suggested that SAIBK2 arose from a series of homologous RNA recombination events from multiple template switches involving a YX10-, a YN-, and a Mass-like strain, and that nsp3, nsp4, nsp12, ORF5, and N gene are involved in the three recombinant events.

Discussion

According to the result of sequence identity analysis based on complete genome, SAIBK2 was most similar to YX10. Subsequently, sequence identity analyses based on partial genomic regions showed that SAIBK2 shared higher similarities with other reference strains than YX10 in some partial genomic regions, as shown in Table 3. These results implicated that recombination events might happen during the evolution of SAIBK2.

In coronaviruses, including IBV, recombinant events efficiently happen and it has been well documented to be responsible for the emergence of new variants [11, 14–16]. To investigate whether recombination events took place during the evolution of SAIBK2. SimPlot analyses were conducted and three recombination events were illustrated in the results (Fig. 3a). The study of sequence identities (Table 4) and phylogenetic analyses (Fig. 3b) based on corresponding regions both further confirmed the results of SimPlot analyses. As the results of sequence identity and SimPlot analyses exhibited, YX10 is the major parent of SAIBK2. YX10 was isolated in Zhejiang province, China in 2010, and caused 25 % mortality in SPF chicken [17, 31]. Compared with YX10, mortality in SPF chicken caused by SAIBK2 was higher (50 %). Considering the recombination events that happened in the procedure of formation of SAIBK2 genome, it is with reason to speculate that the acquisition of the regions from the YN- and Mass-like strains should account for the increased virulence of SAIBK2 compared with YX10. YN was isolated in Yunnan province, China in 2005. It can result in 65 % mortality in SPF chickens [18]. According to the result of SimPlot analyses, SAIBK2 genomic regions of 5888-8102 and 19869-20325 nt were from YN-like strain, and these two regions encode several highly hydrophobic stretches and S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferases (MTase), respectively [19–23]. Meanwhile, Mass-based live attenuated IBV vaccines, including H120, are used extensively in China, and SAIBK2 genomic region of 25329-26224 nt was from Mass-like strain; this region contains Gene 5 and N-terminal domain of N protein. All the three regions above-mentioned involved in recombination events have been documented to act important roles in virus replication [24–30]. Nevertheless, IBV pathogenicity is regulated by multiple genes; these above-mentioned recombination events, together with mutations in the SAIBK2 genome, altered the replication efficiency and resulted in the increased virulence, as observed. However, further investigations by reverse genetic system should provide more profound insight into this issue and increase the understanding of IBV pathogenesis.

China has a large number of chickens and most of them are kept at a rather high density; this situation increased the odds of chicken multiple-infection by several IBV strains. In this case of SAIBK2, YX10- and YN-like strains are very likely to spread in chicken flocks simultaneously; meanwhile, Mass-type live attenuated vaccine was used in the flocks from which we got the disease chickens. Overall, current results provide convincing evidence that SAIBK2 originated from recombination events, in which a YX10-like strain is the major parent and another two strains, a YN- and a Mass-like strains, are the minor parents.

In conclusion, this work implicates that recombination between IBV strains may account for the increasing of IBV virulence. In addition, multiple IBV infection may be a requirement for IBV recombination. Consequently, it continues to be important to put emphasis on surveillance for better control of IBV.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the earmarked fund for Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System (CARS-41-K09), Project for Science and Technology Support Program of Sichuan province (2014NZ0020), and Natural Science Foundation of China (31302094).

Footnotes

Xuan Wu and Xin Yang have contributed equally to the research.

References

- 1.Brierley I, Boursnell ME, Binns MM, Bilimoria B, Blok VC, Brown TD, Inglis SC. EMBO J. 1987;6:3779. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziebuhr J, Thiel V, Gorbalenya AE. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33220–33232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104097200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armesto M, Cavanagh D, Britton P. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodgson T, Casais R, Dove B, Britton P, Cavanagh D. J. Virol. 2004;78:13804–13811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13804-13811.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casais R, Dove B, Cavanagh D, Britton P. J. Virol. 2003;77:9084–9089. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.9084-9089.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavanagh D, Davis PJ, Cook JK, Li D, Kant A, Koch G. Avian Pathol. 1992;21:33–43. doi: 10.1080/03079459208418816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parr RL, Collissor EW. Arch. Virol. 1993;133:369–383. doi: 10.1007/BF01313776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hodgson T, Britton P, Cavanagh D. J. Virol. 2006;80:296–305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.296-305.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casais R, Davies M, Cavanagh D, Britton P. J. Virol. 2005;79:8065–8078. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8065-8078.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Wang H, Wang T, Fan W, Zhang A, Wei K, Tian G, Yang X. Virus Genes. 2010;41:377–388. doi: 10.1007/s11262-010-0517-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang T, Han Z, Xu Q, Wang Q, Gao M, Wu W, Shao Y, Li H, Kong X, Liu S. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015;32:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masters PS. Adv. Virus Res. 2006;66:193–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Ma H, Xu Q, Sun N, Han Z, Sun C, Guo H, Shao Y, Kong X, Liu S. Vet. Microbiol. 2013;162:429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S, Xu Q, Han Z, Liu X, Li H, Guo H, Sun N, Shao Y, Kong X. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014;23:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thor SW, Hilt DA, Kissinger JC, Paterson AH, Jackwood MW. Viruses. 2011;3:1777–1799. doi: 10.3390/v3091777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackwood MW, Boynton TO, Hilt DA, McKinley ET, Kissinger JC, Paterson AH, Robertson J, Lemke C, McCall AW, Williams SM, Jackwood JW, Byrd LA. Virology. 2010;398:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue Y, Xie Q, Yan Z, Ji J, Chen F, Qin J, Sun B, Ma J, Bi Y. J. Virol. 2012;86:13812–13813. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02575-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng J, Hu Y, Ma Z, Yu Q, Zhao J, Liu X, Zhang G. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:1994–2001. doi: 10.3201/eid1812.120552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oostra M, Hagemeijer MC, van Gent M, Bekker CPJ, Te Lintelo EG, Rottier PJM, de Haan CAM. J. Virol. 2008;82:12392–12405. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01219-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanjanahaluethai A, Chen Z, Jukneliene D, Baker SC. Virology. 2007;361:391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Worm SH, Knoops K, Zevenhoven-Dobbe JC, Beugeling C, van der Meer Y, Mommaas AM, Snijder EJ. J. Virol. 2011;85:5669–5673. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00403-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai MM, Baric RS, Brayton PR, Stohlman SA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1984;81:3626–3630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, Su C, Ke M, Jin X, Xu L, Zhang Z, Wu A, Sun Y, Yang Z, Tien P, Ahola T, Liang Y, Liu X, Guo D. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002294. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis JD, Izaurralde E. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;247:461–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwer B, Mao X, Shuman S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2050–2057. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.9.2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuo S, Kao H, Hou M, Wang C, Lin S, Su H. Vet. Microbiol. 2013;162:408–418. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayaram H, Fan H, Bowman BR, Ooi A, Jayaram J, Collisson EW, Lescar J, Prasad BVV. J. Virol. 2006;80:6612–6620. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00157-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurst KR, Ye R, Goebel SJ, Jayaraman P, Masters PS. J. Virol. 2010;84:10276–10288. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01287-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grossoehme NE, Li L, Keane SC, Liu P, Dann CE, Leibowitz JL, Giedroc DP. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;394:544–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Martinez-Sobrido L, Frieman M, Baric RA, Palese P. J. Virol. 2006;81:548–557. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01782-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng K, Xue Y, Wang J, Chen W, Chen F, Bi Y, Xie Q. Vaccine. 2015;33:1113–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]