Abstract

Although gene fusions are recognized as driver mutations in a wide variety of cancers, the general molecular mechanisms underlying oncogenic fusion proteins are insufficiently understood. Here, we employ large-scale data integration and machine learning and (1) identify three functionally distinct subgroups of gene fusions and their molecular signatures; (2) characterize the cellular pathways rewired by fusion events across different cancers; and (3) analyze the relative importance of over 100 structural, functional, and regulatory features of ∼2200 gene fusions. We report subgroups of fusions that likely act as driver mutations and find that gene fusions disproportionately affect pathways regulating cellular shape and movement. Although fusion proteins are similar across different cancer types, they affect cancer type-specific pathways. Key indicators of fusion-forming proteins include high and nontissue specific expression, numerous splice sites, and higher centrality in protein-interaction networks. Together, these findings provide unifying and cancer type-specific trends across diverse oncogenic fusion proteins.

Keywords: gene fusions, cancer genomics, machine learning

Gene fusions are formed via the joining of two previously independent genes, which typically results from structural rearrangements such as translocation. Gene fusions can lead to a deregulation of the involved genes (e.g., overexpression), the formation of a novel fusion protein (e.g., a constitutively active kinase), or the truncation of protein products. The total number of known gene fusions is increasing rapidly, and a growing number of gene fusions have been found to act as driver mutations across diverse cancer types.1,2 For example, gene fusions drive the majority of lymphomas and leukemias,3 and one specific gene fusion (TMPRSS2-ERG) is the most common driver mutation in prostate cancer.4 In accord with their importance to cancer-related processes, gene fusions and their products have been useful as drug targets, as well as diagnostic, prognostic, and cancer subtype biomarkers.5,6 A recent analysis of over 25000 fusions present in the TCGA database estimates that fusions drive the development of 16.5% of cancer cases (functioning as solve drivers in over 1% of cases), and that 6.0% are potentially druggable by fusion-targeted treatments.7

Several studies have sought to broadly characterize the functional trends present in gene fusions and fusion proteins. For example, studies have addressed fusion protein interactions and regulation,8 domain content,9−14 intrinsic structural disorder,15,16 expression levels,2,11,17−21 and fusion pairing networks.9−11,22,23 Such work has shed light on a variety of functional trends, such as the tendency of fusions to involve kinases,24,25 chromatin modifying proteins,26,27 and highly expressed “parent” genes that are involved in the fusion.11 However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has sought to identify the molecular signatures or functional subgroups of gene fusion events, or the hallmarks of gene fusion in terms of describing the trends in the rewiring of cellular pathways resulting from fusion.

Here, we first compile a genome-wide, protein-centric feature set of over 100 attributes–including data on gene function, protein structure, molecular interactions, gene expression, regulatory sites and tissue-specificity–in order to ask a series of questions about the functions of gene fusion events (Figure 1A). We focus exclusively on the properties of parent proteins and fusion proteins, and hence do not consider DNA or RNA-level features (promoter architectures, epigenetic states, miRNA targets, UTRs, etc.). To infer the molecular signatures and hallmarks of fusion proteins, we use unsupervised clustering to find groups of functionally similar gene fusions (Figure 1B) and identify the pathway rewiring trends of known fusions (Figure 1C). We also use statistical learning algorithms to infer feature importance (Figure 1D) across a variety of predictive tasks, for example, to find attributes predictive of proteins involved in fusion events, fusion recurrence, etc. Only a handful of previous studies have used machine learning techniques to model or predict any aspect of gene fusion biology,13,28−30 all focusing on distinguishing driver and passenger fusion events. The specific findings, general trends, and predictive framework presented here will be useful for (i) facilitating a deeper molecular understanding of the role of gene fusions in cancer and (ii) identifying novel therapeutic strategies for developing pharmacological agents, targeting specific pathways to counter the oncogenic effects of diverse cancer gene fusions.

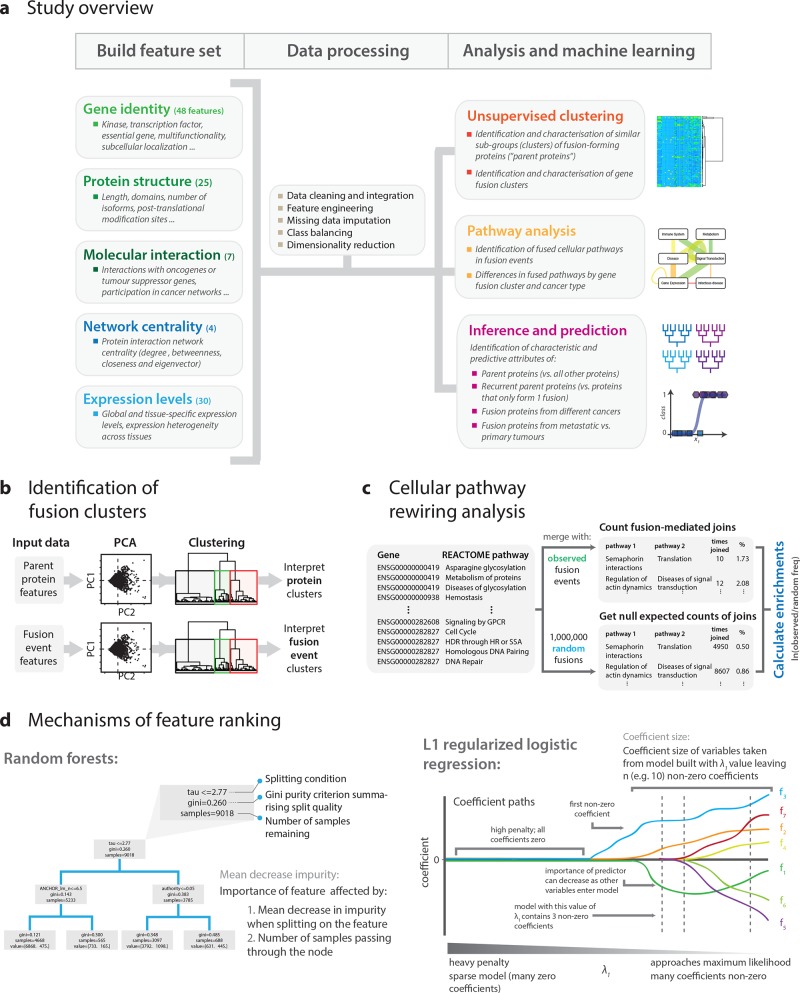

Figure 1.

Study overview. (a) Data sets describing the function, structure, interactions, and expression of human proteins were integrated with a gene fusion data set in order to identify the molecular signatures, hallmarks, and investigate the functional molecular biology of fusion events in cancer. (b) Clusters of fusion-forming proteins (i.e., “parent proteins”) and fusion proteins (each composed of two parent proteins) were identified by principal components analysis followed by agglomerative hierarchical clustering. (c) Cellular pathways significantly rewired by fusion events were identified using randomization tests that compared pathway fusion frequencies to expected null counts. (d) Random forest (RF) and regularized logistic regression (RLR) models were used to infer feature importance across a variety of classification tasks, such as ranking which properties best distinguish between parent proteins and nonfusion forming proteins. The mechanisms of feature importance ranking by the two models are outlined (see Online Methods in the Supporting Information for details).

Results

Feature Space Construction

We curated and integrated genome-wide data from 25 data sets and papers to compose a feature set of 119 variables (names, descriptions, and data sources in Table S1) that may influence fusion protein function, as suggested by a review of current literature.5 Only protein-coding genes (n = 20295) were considered. A gene fusion data set containing 2371 in-frame fusion events, resulting from a recent transcriptomic screen of 675 human cancer cell lines,31 was used as the known gene fusion set. For prediction tasks, the data set was balanced according to outcome class frequencies (see Online Methods) before being input to learning algorithms.

Molecular Signatures of Parent Proteins Involved in Gene Fusions

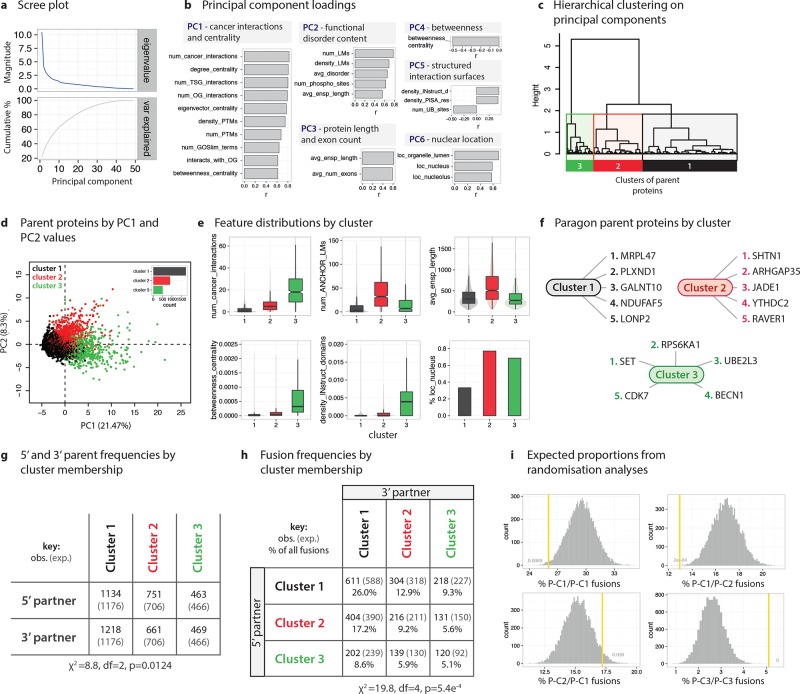

Gene fusions generally involve two genes (i.e., two “parent genes” or “parent proteins”). We first examine whether natural subgroups of parent proteins can be identified, and what characterizes each subgroup (or “cluster”). Principal components analysis (PCA) was conducted on parent protein features (Figure 2A) to identify axes on which parent proteins vary most (Figure 2B). The largest axis of variance (principal component 1, PC1; 21.5% of total variance) captures aspects of a parent protein’s position in protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks (using different measures of “centrality” to a network) and its interactions with cancer proteins (e.g., oncoproteins and tumor suppressor proteins), such that proteins with high PC1 values have higher network centrality and more interactions with cancer proteins; PC2 (8.3%) reflects elements associated with intrinsic structural disorder, such as the presence of linear peptide binding motifs (LMs), etc. (see Figure 2B for PC3 to PC6 correlations). We identify three clusters of parent proteins (Figure 2C,D). These groups are described by their functional and structural properties (Figure 2E), by average cases or “paragons” (Figure 2F), and by functional enrichments by cluster (Figure S1). The three parent protein clusters are

-

1.

Structured and isolated proteins (P1). A large cluster (n = 1742; parent cluster 1 or P1) of poorly interactive, structurally ordered proteins, which are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and are isolated from oncogenic processes, that is, have few interactions with cancer proteins (Figure 2D,E). P1 proteins have few interaction-mediating elements (such as certain domains and LMs) and relatively rarely localize to the nucleus. Functionally, P1 proteins are most dramatically enriched for protein localization and protein transport (Figure S1). Paragon P1 proteins (Figure 2F) include the mitochondrial ribosomal protein L47 (MRPL47) and the cell–cell signaling and migration protein plexin D1 (PLXND1).

-

2.

Disordered, nuclear cell cycle proteins (P2). An intermediate-sized cluster (n = 898) of large, disordered, LM and post-translation modification (PTM) rich proteins with low/intermediate PPI centrality and number of cancer interactions. P2 proteins are enriched for cell division, cell cycle, and transcription functions. Paragon P2 proteins (Figure 2F) include the neurite outgrowth and cytoskeletal organization protein shootin 1 (SHTN1) and the DNA binding factor Rho GTPase activating protein 35 (ARHGAP35).

-

3.

Central connector and cancer interactor proteins (P3). A small cluster (n = 504) of highly central, PTM-dense, multifunctional, nucleus-localized proteins with numerous interactions with cancer proteins. P3 proteins are smaller, more ordered, and much more interaction-prone and central in PPI networks than P2 parents. P3 proteins are highly enriched for roles in protein production and processing, for example, translation and RNA splicing, as well as cell division, cell cycle, and cell death. Interestingly, alteration of splicing has been demonstrated as a key oncogenic mechanism of the PPI network hub EWS-FLI1 fusion protein, an important oncoprotein in Ewing sarcoma.32 Paragon P3 proteins (Figure 2F) include the SET nuclear proto-oncogene, and the mitogen-activating RPS6KA1 kinase (involved in cell proliferation and survival).

Figure 2.

Molecular Signatures of Fusion: Identification and characterization of parent protein subgroups. (a) Scree plot showing the eigenvalues and cumulative variance explained by successive principle components (PCs). (b) Loadings on the PCs showing the correlations (r) between features and the first 6 PCs. Headers to PC boxes conceptually summarize the correlations. Variable names, descriptions, and data sources are available as Table S1. Shortened variable names used for display purposes: num_LMs, num_ANCHOR_LMs; density_LMs, density_ANCHOR_LMs; density_INstruct_d, density_INstruct_domains. (c) Hierarchical clustering was performed on the values of the first 10 PCs, yielding three clusters of parent proteins. (d) Parent proteins plotted by PC1 and PC2 values, colored by cluster. (e) Distributions of key features by cluster. The features chosen highly correlate with the first six PCs. (f) Paragon parent proteins are instances closest to cluster centroids, and therefore represent “average” cases for the cluster. Five paragon examples (i.e., the five points closest to the centroid) are provided for each cluster. (g) Frequencies of parent proteins acting as either the 5′ or 3′ parent by cluster. (h) Fusion frequencies by cluster membership and 5′ versus 3′ parent status. (i) Expected proportions of intercluster fusions derived from randomization analyses. Random fusions were generated by sampling twice from the three parent cluster gene sets.

For the majority of enriched molecular functions, there is a clear functional separation by cluster; for example, only P3 parents are significantly enriched in translation, splicing, and cell death functions (Figure S1A, S1B). The data used for clustering did not include specific GO function annotation. Certain functions, such as mitosis, the cell cycle, and nitrogen metabolism, are enriched across multiple clusters (P2 and P3). The sole biological process enriched across all parent clusters is “RNA metabolic processes”, which encompasses RNA synthesis, modification, and processing.

Parent proteins from each cluster act as 5′ or 3′ parent genes at approximately statistically expected rates, though P1 proteins tend toward being 3′ parents and P2 toward 5′ parents (Figure 2G; χ2 = 8.8, df = 2, p = 0.0124). P2 and P3 parents are much more likely to be recurrent (i.e., participate in multiple fusions), a marker of driver mutations (% recurrent parents in P1, 24.7%; P2, 32.6%; P3, 41.1%; χ2 = 55.5, df = 2, p = 8.9e–13). Overall, the largest proportion of fusion events (30.2%) fuse P1 and P2 proteins (P1 + P2 or P2 + P1); P1 + P1 fusions are also abundant (26.0%) (Figure 2H). Fusion frequencies by parent cluster deviate from expected values, suggesting preferential pairing between certain clusters (Figure 2H; χ2 = 19.8, p = 5.4e–4). A follow-up randomization analysis (see Online Methods) showed that P1 + P1 fusions and P1 + P2 fusions occur less often than expected, while P3 + P3 and P2 + P1 fusions are disproportionately common. Hence, there exist functionally distinct clusters of parent proteins with observable pairing biases between them.

Functional and Molecular Clustering of Fusion Events

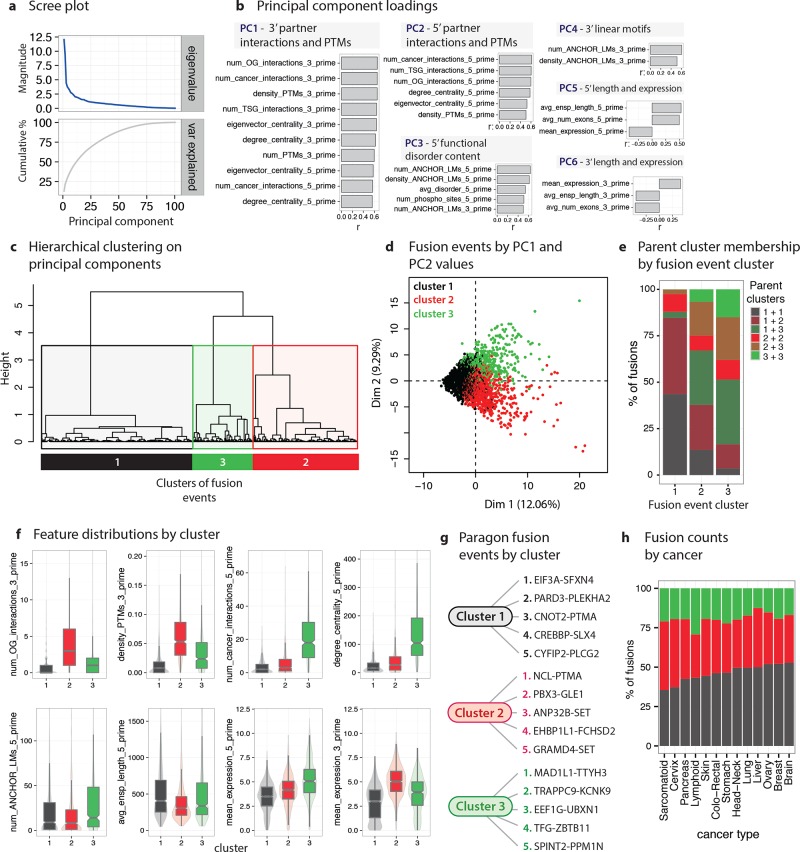

Next, subgroups of entire fusion proteins (consisting of two fusion parents; see above) were identified. Specifically, PCA and clustering analyses were conducted on the features of 2362 fusion events detected in 675 cancer cell lines. Interestingly, the axes on which fusion events differ most are nearly perfectly separated into 5′ versus 3′ parent features. Fusion principal component 1 (F-PC1; 12.1% of variance; Figure 3A) captures 3′ parent PPI network centrality and interactions with cancer proteins (Figure 3B) while F-PC2 (9.3%) captures the 5′ parent version of F-PC1, correlating with the centrality and cancer interactions of 5′ parents. F-PC3 (4.4%) quantifies 3′ parent functional disorder, and F-PC4 (3.7%) captures 5′ linear motifs (strongly associated with disorder). From these PCs, three clusters of fusion events were identified (Figure 3C,D), which incorporate parent protein clusters at different rates (Figure 3E), namely:

Figure 3.

Molecular signatures of fusion: Identification and characterization of gene fusion subgroups. (a) Scree plot showing the eigenvalues and cumulative variance explained by successive PCs. (b) Loadings for the first 6 PCs. (c) Clusters of gene fusion events emerging from hierarchical clustering on the first 10 PCs. (d) Fusion proteins plotted by PC1 and PC2 values, colored by cluster. (e) Composition trends of fusion events by cluster. For each of the three fusion event clusters, the proportions of fusions arising from different combinations of proteins from the previously identified parent protein clusters (see Figure 2) are shown. (f) Distributions of key features of fusion events colored by cluster. (g) Paragon gene fusion events by cluster. (h) Prevalence of the three gene fusion clusters among a range of cancer types.

(1) Structured, peripheral fusion proteins (F1): A large cluster (n = 1126; fusion cluster 1 or F1) of fusions composed of large, relatively structurally ordered, functionally specialized 5′ and 3′ proteins characterized by low PPI centrality, few interactions with cancer proteins, few PTMs, and low, tissue-specific expression (Figure 3D,F). F1 fusions are most often composed of parents from the P1 and P2 clusters (specifically, P1/P1 and P1/P2 combinations make up 84.6% of F1 fusions; see above for parent cluster descriptions), with almost no involvement of P3 parents. Paragon F1 fusions are diverse (Figure 3G), and include fusions between a translation initiation factor (EIF3A) and mitochondrial membrane protein (SFXN4); a cell division (PARD3) and a signaling (PLEKHA2) protein; an mRNA processing (CNOT2) and cell survival and proliferation (PTMA) protein; and a transcriptional coactivation (CREBBP) and DNA repair (SLX4) protein.

(2) Fusion proteins with central, regulated, and cancer-associated 3′ parents (F2). An intermediate-sized cluster (n = 778) of fusions in which the 3′ parents are characterized by high PPI centrality, connectivity to cancer proteins, and multifunctionality. F2 3′ parents have high and broad expression, and many PTMs and interaction-mediating regions. The 5′ parents in F2 fusions do not have such extreme features, and more resemble P1 parents. Typical F2 fusions include a ribosome maturation protein (NCL) with PTMA; a transcription regulator involved in leukaemogenesis33 (PBX3) and an mRNA export mediator (GLE1); cell cycle progression protein (ANP32B) and the SET proto-oncogene.

(3) Fusion proteins with central, regulated, and cancer-associated 5′ parents (F3). Conversely, in the final small cluster (n = 448) of fusions, the 5′ but not the 3′ parents are characterized by high centrality, cancer interactions, high PTM densities, expression levels, etc. (Figure 3B,F). Prototypical F3 fusions often involve proteins functioning in processes classically associated with cancer,34 for example, a mitotic checkpoint protein (MAD1L1) and a chloride anion channel (TTYH3); an activator of NF-kappa-B signaling (TRAPPC9) and a potassium channel (KCNK9); and a translation elongation factor (EEF1G) and a regulator of NF-kappa-B signaling (UBXN1).35

These results demonstrate the existence of distinct subgroups of fusion events that share common functional and structural themes, especially with respect to 5′ versus 3′ parent properties. F1 and F3 fusions are slightly more likely to be detected in metastatic tumors (% of fusions classed as metastatic in F1:9.7%; F2:7.0%; F3:12.1%; χ2 = 9.3, df = 2, p = 9.4e–3; see Online Methods). Although cancer types have different proportions of fusions from each cluster (Figure 3H; for example, brain cancers have the highest proportion of F1 fusions; sarcomatoid cancers F2 fusions; lymphoid cancers F3 fusions, etc.), these differences do not reach significance (χ2 = 19.2, df = 16, p = 0.26).

Fusions Disproportionately Rewire Signaling and Cell Movement Pathways

To investigate fusion hallmarks, that is, which pairs of cellular pathways are most often joined by fusions, REACTOME gene pathway annotation was mapped onto parent proteins in fusion events. Across all fusions, signal transduction pathways are the most frequently rewired (Table S2), with “signal transduction” often being paired with “immune system” (in 14.7% of fusions), “metabolism” (12.3%), other “signal transduction” (11.7%), “gene expression” (11.5%), and “disease” (10.5%) pathways. To identify which pairs of pathways are fused more than expected by chance, empirical frequencies were compared to frequencies derived from 1 000 000 randomly generated gene fusions (see Online Methods).

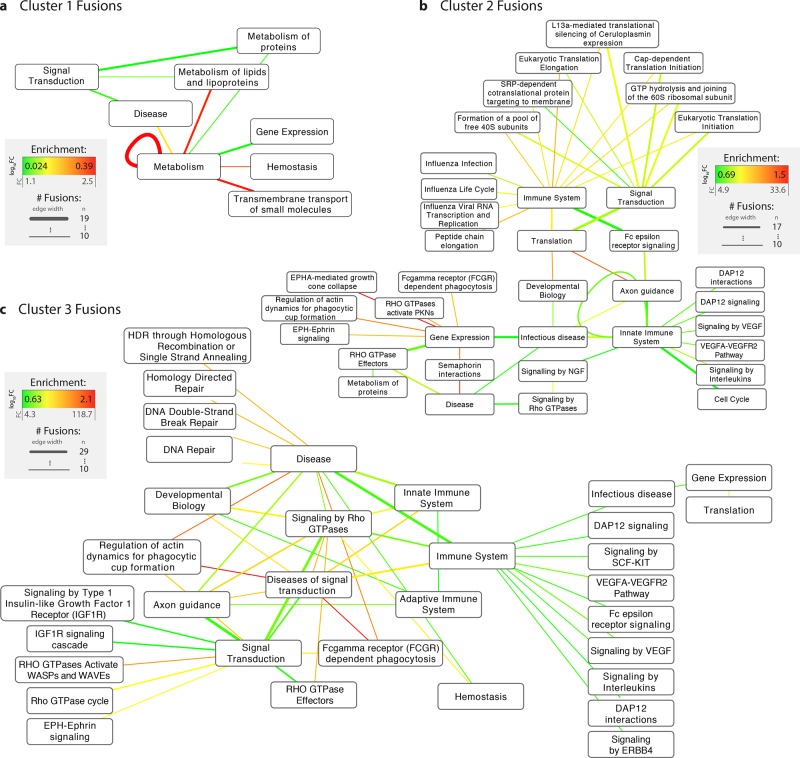

Signaling and cell movement pathways—especially RHO GTPase and semaphorin signaling, and actin dynamics—are the most disproportionately frequently rewired by fusions (Figure S2; Table S2). For example, the pairing of “diseases of signal transduction” and “RHO GTPases Activate WASPs and WAVEs” (involved in cytoskeletal signaling) is expected to occur at a rate of 0.0273% by chance (∼1 in 3663 fusions) while the observed rate is 1.748% (∼1 in 57), giving an enrichment of over 64 (log10 enrichment of 1.8). We observe an abundance of rewired pathways involving semaphorins (which regulate cell adhesion, motility, and tumor progression), semaphorin 4D (“sema4D” or “CD100”; a transmembrane semaphore involved in cell migration as well as immune signaling and angiogenesis), and other pathways relating to actin dynamics and cell movement. Pathway fusions were recalculated by fusion event clusters (Figure 4), showing the following:

-

1.

F1 fusions are minor contributors to cellular pathway rewiring. The largest cluster of fusion events has the smallest number of enriched pathway fusions. The existing enrichments are slight and largely related to metabolism.

-

2.

F2 fusions link cell movement with gene expression and rewire translation. F2 fusions connect cell movement (actin dynamics, growth cone collapse, EPH-Ephrin signaling, phagocytosis) with gene expression pathways, and fuse translation-related pathways with signal transduction and immune signaling processes.

-

3.

F3 fusions affect cell movement, signaling, and DNA repair. F3 fusions also highly affect phagocytosis, actin dynamics, and cell movement, in addition to DNA repair processes and other signaling pathways. Both F2 and F3 fusions combine immune system signaling with VEGF (promoter of angiogenesis) and DAP12 (immune cell activation) signaling.

Figure 4.

Fusion hallmarks: trends in cellular pathways fusions by fusion event cluster. REACTOME gene pathway annotation was mapped onto parent proteins in fusion events and enrichment was assessed using randomization analyses. Nodes indicate pathways, and edges indicate the occurrence of a fusion between them (i.e., between two genes which participate in the pathways). Edge widths denote the number of unique fusion events associated with a specific pathway fusion, and edge colors represent enrichments, whereby enrichments are calculated as the log10 fold change between observed fusion frequencies and expected frequencies derived by randomly pairing any two human protein-coding genes 1 000 000 times (see Online Methods). Using only parent proteins as the sampling set for generating background frequencies results in highly similar results (see Figure S2). Only pathways that were fused in 10 or more different fusion events are shown.

Specific cases of fused pathways can be used to generate mechanistic hypotheses; for example, the fusion between translation and pathways related to cell movement (e.g., semaphorin interactions) could relate to the localized translation of proteins involved in cell motility at the cell movement boundary,36,37 while the fusion of gene expression pathways to PAK signaling could influence PAK-related oncogenic signaling.38

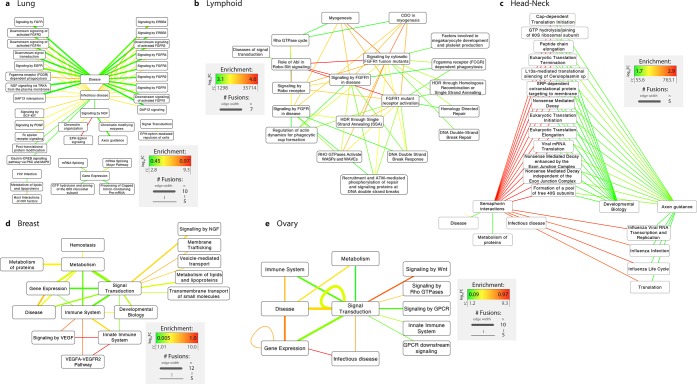

Cancer Type Specific Similarities and Differences in Pathways Affected by Fusion

Fusion protein properties (e.g., expression, protein domains, regulatory sites) do not significantly differ across eight cancer types, as evidenced by a low overall accuracy of classification algorithms trained on these properties (see Table S4). Despite this protein-level similarity, the fusion-mediated pathway rewiring trends vary substantially by cancer type (Figure 5):

-

1.

Lung cancer fusions commonly link signaling pathways with processes labeled as being related to disease, such as the fusions involving various fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR; often targetable mutations, including FGFR fusion proteins39,40) pathways and fusions involving DAP12 immune signaling.41 Fusions between NGF signaling and EPH-Ephrin signaling pathways are also highly enriched.

-

2.

Lymphoid cancer fusions most substantially rewire Slit-Robo (cell guidance and angiogenesis) and FGFR signaling (cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival), as well as affecting DNA repair processes and cell adhesion.

-

3.

Head-neck cancer fusions frequently pair cell movement with translation and mRNA decay pathways. Interestingly, pathways related to infectious disease (particularly, influenza) are also frequently affected, which may relate to the link between inflammation, infection, and carcinogenesis.42,43

-

4.

Breast cancer fusions are most enriched for connecting VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor; an established promoter of angiogenesis and metastasis in breast cancer44,45) pathways with immune system pathways, and also affect membrane trafficking.

-

5.

Ovarian cancer fusions tend to affect gene expression pathways, Wnt signaling (ovarian cancer initiation and development), and Rho GTPase signaling.

Figure 5.

Fusion hallmarks: trends in cellular pathway fusions by cancer type. Enrichments in pathway fusions were calculated as before. Only pathways that were fused in five or more different fusion events are shown. The five displayed cancer types were chosen due to their availability of pathway annotation and of a sufficiently high number of gene fusions.

Hence, although fusion protein characteristics are broadly similar across cancer types (and across primary vs metastatic tumors; see Figure S5), the pathways they affect are specific to the cancer type.

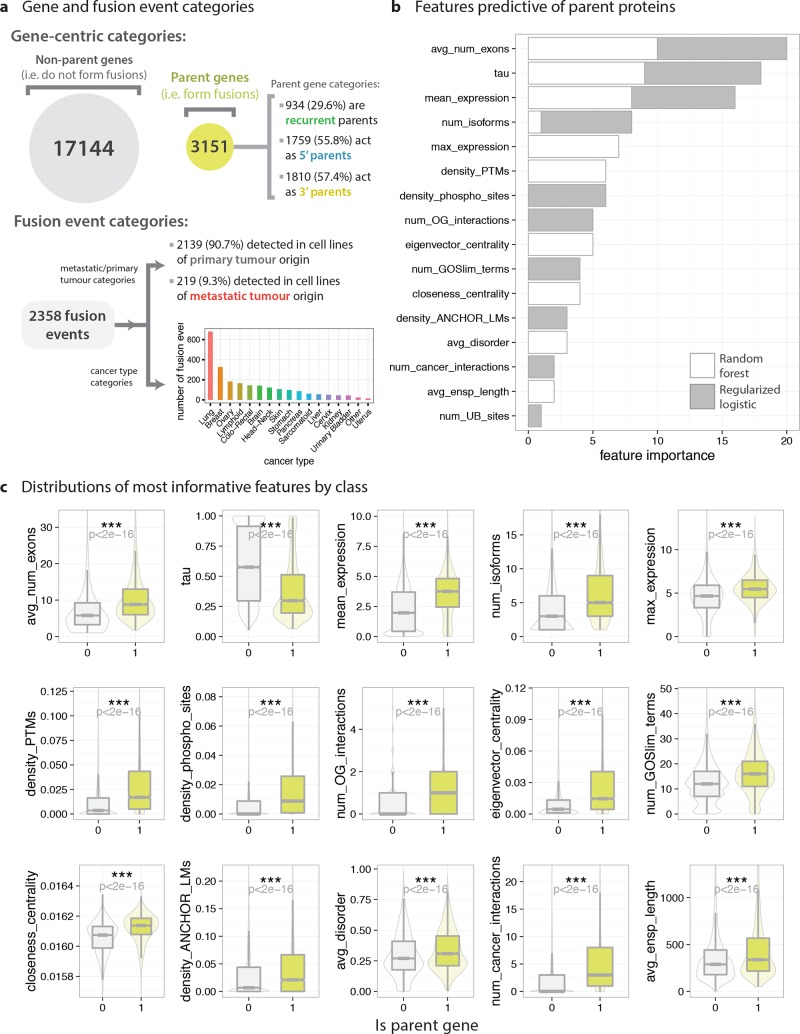

Features Distinguishing Parent and Nonparent Genes

Random forest (RF) and regularized logistic regression (RLR) classifiers, chosen for their different formulations and ability to generate interpretable feature rankings, were trained to distinguish parent and nonparent proteins on a balanced data set (Figure 6A; nparent = nnonparent = 3151). The most influential features were aggregated across both models (Figure 6B; variable definitions are available in Table S1), and distributions of these key features were visualized (Figure 6C). Models trained on the gathered feature set can differentiate between parent and nonparent genes moderately well (overall accuracy: RF = 0.674, RLR = 0.683 with 10 features, RLR = 0.686 with CV-optimized λ1), with both models ranking similar features as highly predictive of parent proteins. As a baseline,46 predicting parent proteins using cancer gene labels achieves 52.1% accuracy (random chance: 50.0% accuracy). Parent proteins have more exons and isoforms, are more highly expressed, expressed across more tissues, more molecular functions, higher PPI network centrality, interact with many oncogenes and other cancer proteins, and contain many disorder-associated elements such as PTMs and LMs. Several of these features have not been previously implicated in a significant manner with fusion protein functionality (e.g., multifunctionality).

Figure 6.

Predictive characteristics of fusion parent proteins. RF and RLR models were trained to distinguish between parent proteins and all other proteins on the basis of their gene- and protein-level properties (or features) on a balanced data set. (a) Categories of parent genes and fusion events within the data set, used as target labels for subsequent classification tasks. (b) Most informative features for distinguishing parent proteins from nonparent proteins, as ranked by the random forest and regularized logistic regression models. Higher values in stacked bar plots indicate higher predictive importance (see Figure 1d and Online Methods for details). Feature rankings are returned in highly different formats by the RF and RLR models, but were made comparable by considering ordinal rankings only. (c) Distributions of most predictive variables for parent proteins (lime green) and nonparent proteins (light gray). Boxplots (with outliers removed) are overlaid on violin plots. Differences in distributions were quantified using nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum tests (for numerical variables), chi-squared tests (categorical data), and Fisher’s exact tests (categorical data where any cell count is less than 30).

All human proteins were ranked by their “similarity” to known parent proteins (Table S3) on the basis of the RF and RLR model predictions—which agree on 79% of parent/nonparent labels in the human proteome, despite highly different model formulations. For example, the three most “fusion parent-like” proteins (Table S3) are SRRM2 (serine/arginine repetitive matrix 2; pre-mRNA splicing, associated with papillary thyroid carcinoma), APP (amyloid beta precursor protein; protein synthesis, cell proliferation, and cancer cell migration), and MACF1 (microtubule-actin cross-linking factor 1; cytoskeleton organization protein facilitating peripheral actin-microtubule interactions and regulating cell migration). Examples of predicted highly “parent-like” proteins not currently classified as parents (in this data set), include CTNND1 (catenin delta 1; cell–cell adhesion, and signal transduction), NUMA1 (nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1; cell division), EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor; a receptor tyrosine kinase involved in cell proliferation signaling), TLN1 (talin 1; actin filament assembly, cell adhesion and cell migration), and TOP2B (topoisomerase DNA II beta; nuclear enzyme which alters DNA topology during transcription). As a brief validation of these rankings, we note that CTNND1,47 NUMA1,48 EGFR,49 and TOP2B50 gene fusions have indeed been described in the literature.

5′ and 3′ Parent Proteins Are Functionally and Structurally Similar

Gene fusion generally involves two different parent genes, one acting as the 5′ parent and the other as the 3′ parent. The pairing of genes in fusion events has been suggested to be nonrandom at the level of genes and domains.11 We trained models to distinguish between 1341 5′ and 1392 3′ parents (excluding genes which act as both 5′ and 3′ parents; Figure S4A) and analyzed features most predictive of each category (Figure S4B). Despite some differences in properties (Figure S4C; for example, 3′ parents are expressed at lower levels and more tissue-specifically), models could classify 5′ and 3′ parent genes at a rate only slightly higher than chance (accuracy: RF = 0.554, RLR = 0.550 with 10 features, RLR = 0.552 with CV-optimized λ1). This indicates the absence of a strong difference between 5′ and 3′ parent genes at the level of protein features and gene functions. However, DNA- or RNA-level features such as promoter strength may still separate 5′ and 3′ parents, as has been previously suggested.11

Observed 5′–3′ Fusion Pairings Are Not Distinguishable from Random 5′–3′ Pairings

To examine whether the specific pairing pattern between 5′ and 3′ parent genes is nonrandom, models were trained to distinguish between real and random combinations of known 5′ and 3′ parents. Random events were generated by sampling from a matrix of all possible fusion events (Figure S5A; Online Methods) and models were trained. In line with our previous result that 5′ and 3′ parent proteins are largely identical (Figure S5B–D), the classifiers performed comparably to random chance. For example, both the random and real fusions possessed an oncogene 5′ parent and a nononcogene 3′ parent in ∼2.4% of the cases, and had a kinase 5′ parent and nonkinase 3′ parent in ∼4.3% of the cases. This suggests that fusion events may simply incorporate two “parent-like” genes, with the specific genes and 5′-3′ ordering being relatively unimportant (at the protein level), though the order is undoubtedly important for specific individual cases and for their expression level in different cancer types.22

Characteristic Features of Recurrent versus Nonrecurrent Parent Genes

Recurrence has been suggested to be a marker of driver fusion mutations.25,51 Within the set of parent genes (n = 3151), 934 (29.6%) are recurrent parents (i.e., they form more than 1 fusion within the data set; Figure S6A). Recurrent parents are much more likely to participate in fusions detected in cell lines derived from metastatic (versus primary) tumors (Fisher’s exact test odds ratio = 2.46, p < 2.2e–16), suggesting a link between recurrence and cancer progression (Figure S6B). On the basis of protein features, recurrent parent proteins are relatively poorly distinguishable from genes that form two or more fusions (overall accuracy: RF = 0.561, RLR = 0.546 with 10 features, RLR = 0.560 with CV-optimized λ1). The list of predictive features is largely the same as the collection of features that best split parent genes from nonparents (e.g., higher and broader expression, more exons and isoforms; Figure S6C,D), suggesting that recurrent parent genes are “more extreme” versions of parent genes. Indeed, certain properties gradually increase with how many fusions a gene forms, including expression heterogeneity, expression levels, PTM density, interaction-mediating domains, and interactions with cancer proteins (Figure S7A), and increasingly recurrent genes are therefore easier to identify (classification accuracies in Figure S7B; recurrence class sample sizes in Figure S7C). Genes that form 5+ fusions are as highly distinct from nonrecurrent parents as parents are from nonparents, when judged by classification accuracies (Figure S7B).

Discussion

Given the rapidly growing evidence that gene fusions are frequent driver mutations across a wide variety of cancer types,5,7,22 a deeper understanding of the molecular and functional signatures of fusion is essential. We hope that the functional trends in this manuscript will be useful for both exploratory and translational efforts such as the detection and prioritization of novel gene fusions,5 studies of the druggability of gene fusions,7 cancer-focused knowledge bases supporting translational research52 and more broadly, network- and proteomics-based approaches to identifying new therapeutics and therapeutic avenues.53−55 As pharmacological agents are developed against specific fusion transcripts and proteins6 and the medical targeting of entire pathways is refined, the broad overview of the types of processes affected by numerous gene fusions provided in this study could help guide and focus research efforts.

In this work, we integrated large data sets of gene- and protein-level features and mined information on fusion protein functionality, such as the major classes of fusion proteins (e.g., two groups of fusions with characteristics of oncogenic driver mutations were identified; Figures 2 and 3), their effects on cellular pathways (e.g., high impact on cellular shape and movement pathways; Figures 4 and 5, Figure S2), and which features are predictive of a protein’s involvement in fusions (e.g., higher propensity for splicing, central positioning in protein interaction networks; Figure 6). The properties of the largest fusion event cluster (F1) are not traditionally associated with cancer-related proteins. This may point toward underexplored oncogenic mechanisms, or may simply reflect neutral passenger fusions (potentially due to the cell line origin of the fusions). Gene fusions from different cancer types were placed within the three functional clusters at comparable rates, suggesting that type-specific proportions of driver versus passenger fusions are similar. Despite the largest cluster of fusion proteins being relatively inert (e.g., lowly expressed, few interactions, sparsely regulated), certain structural and interactomic features (e.g., phosphorylation sites, ubiquitination sites, linear motifs, the number of interactions with cancer proteins) were key predictors of a gene’s involvement in fusion events, more so even than whether the gene is itself a cancer gene. This is reflective of the extreme characteristics of fusion proteins from the two remaining clusters (Figure 2, Figure 6). Previous work has shown that many interaction-mediating modules and PTM sites of parent proteins are excluded from fusion proteins due to fusion breakpoint placement,8 suggesting a loss-of-function theme to fusion mutations and aligning with previous work of disease mutations leading to a loss of regulatory56 and interaction-mediating sites.57,58 Future work can elucidate feature gain/loss patterns across clusters of fusion events.

While gene and transcript fusion occurs at the DNA and RNA level, selection generally operates at the protein level (provided that transcripts are viable and undergo translation). Therefore, in this study, protein-level features of fusion events were studied. The specific questions for which no significant differences were found (e.g., the high similarity between 5′ and 3′ parents, and the randomness of 5′/3′ pairing patterns) could point toward DNA and RNA level properties (e.g., promoter properties, 3D nuclear location, replication timing, epigenetic states, etc.) taking precedence over protein-level features in the underlying phenomena.

Finally, despite evidence that point mutation patterns differ across cancer types,59−63 and gene fusions in many cases being cancer type specific,3 we find that fusion proteins from different cancer types are highly similar at the function and pathway levels (Figure 5). However, different pathways specific to cancer type are rewired by fusions. Future work could in more detail study how fusion protein functionality is affected across human tissues and cancer stages, thereby building on the expanding body of research surrounding tissue-specific interactomes in disease58,64,65 and cancer subtype specific trends in driver genes.62,66

In conclusion, the specific findings and general trends presented in this work provide molecular insights into the functional patterns present across diverse oncogenic fusion proteins, which may help elucidate the roles that the thousands of known (and yet to be detected) fusion mutations play in cancer.

Methods

Methods and any associated references are available in the Supporting Information files that accompany this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank the MRC for funding our research (MC_U105185859). We thank Nadezda Kryuchkova and Marc Robinson-Rechavi for early access to the expression breadth calculations from their tissue-specificity methods benchmarking paper; Joelle Goeman for a patched version of “penalized” R package prior to release on CRAN; and Charles Ravarani for helpful discussions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CV

cross-validation

- LM

linear peptide binding motif

- PCA

principal components analysis

- PPI

protein–protein interaction

- PTM

post-translational modification

- RF

random forest

- RLR

regularized logistic regression

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsptsci.9b00019.

Table of contents, the online methods, online methods references, legends for supporting figures and supporting Figures S1−S7 (PDF)

Table S1: Data set description. Table S2: Cellular pathway fusions. Table S3: Parent protein predictions. Table S4: Cancer type prediction from fusion protein features (ZIP)

Author Contributions

N.S.L. designed the study, performed the analyses, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript; M.M.B. contributed to study design, interpretation of the results, manuscript writing, and supervised the project. N.S.L. and M.M.B. read and approved the final version of the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Watson I. R.; Takahashi K.; Futreal P. A.; Chin L. (2013) Emerging Patterns of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14 (10), 703–718. 10.1038/nrg3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara K.; Wang Q.; Torres-Garcia W.; Zheng S.; Vegesna R.; Kim H.; Verhaak R. G. W. (2015) The Landscape and Therapeutic Relevance of Cancer-Associated Transcript Fusions. Oncogene 34 (37), 4845–4854. 10.1038/onc.2014.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobato M. N.; Metzler M.; Drynan L.; Forster A.; Pannell R.; Rabbitts T. H. (2008) Modeling Chromosomal Translocations Using Conditional Alleles to Recapitulate Initiating Events in Human Leukemias. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 39, 58–63. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam R. K.; Sugar L.; Yang W.; Srivastava S.; Klotz L. H.; Yang L.-Y.; Stanimirovic A.; Encioiu E.; Neill M.; Loblaw D. A.; et al. (2007) Expression of the TMPRSS2:ERG Fusion Gene Predicts Cancer Recurrence after Surgery for Localised Prostate Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 97 (12), 1690–1695. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latysheva N. S.; Babu M. M. (2016) Discovering and Understanding Oncogenic Gene Fusions through Data Intensive Computational Approaches. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (10), 4487–4503. 10.1093/nar/gkw282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar-Sinha C.; Kalyana-Sundaram S.; Chinnaiyan A. M. (2015) Landscape of Gene Fusions in Epithelial Cancers: Seq and Ye Shall Find. Genome Med. 7 (1), 129. 10.1186/s13073-015-0252-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q.; Liang W.-W.; Foltz S. M.; Mutharasu G.; Jayasinghe R. G.; Cao S.; Liao W.-W.; Reynolds S. M.; Wyczalkowski M. A.; Yao L.; et al. (2018) Driver Fusions and Their Implications in the Development and Treatment of Human Cancers. Cell Rep. 23 (1), 227. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latysheva N. S.; Oates M.; Maddox L.; Flock T.; Gough J.; Buljan M.; Weatheritt R. J.; Babu M. M. (2016) Molecular Principles of Gene Fusion Mediated Rewiring of Protein Interaction Networks in Cancer. Mol. Cell 63, 579. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Mendíbil I.; Vizmanos J. L.; Novo F. J. (2009) Signatures of Selection in Fusion Transcripts Resulting from Chromosomal Translocations in Human Cancer. PLoS One 4 (3), e4805 10.1371/journal.pone.0004805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman F.; Johansson B.; Mertens F. (2007) The Impact of Translocations and Gene Fusions on Cancer Causation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7 (4), 233–245. 10.1038/nrc2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shugay M.; Ortiz de Mendíbil I.; Vizmanos J. L.; Novo F. J. (2012) Genomic Hallmarks of Genes Involved in Chromosomal Translocations in Hematological Cancer. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8 (12), e1002797 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel-Morgenstern M.; Valencia A. (2012) Novel Domain Combinations in Proteins Encoded by Chimeric Transcripts. Bioinformatics 28 (12), i67–74. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-S.; Prensner J. R.; Chen G.; Cao Q.; Han B.; Dhanasekaran S. M.; Ponnala R.; Cao X.; Varambally S.; Thomas D. G.; et al. (2009) An Integrative Approach to Reveal Driver Gene Fusions from Paired-End Sequencing Data in Cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 27 (11), 1005–1011. 10.1038/nbt.1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S.; Sasaki S.; Morita H.; Oki Y.; Turiya D.; Ito T.; Misawa H.; Ishizuka K.; Nakamura H. (2010) The Role of the Amino-Terminal Domain in the Interaction of Unliganded Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma-2 with Nuclear Receptor Co-Repressor. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 45 (3), 133–145. 10.1677/JME-10-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi H.; Buday L.; Tompa P. (2009) Intrinsic Structural Disorder Confers Cellular Viability on Oncogenic Fusion Proteins. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5 (10), e1000552 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korla P. K.; Cheng J.; Huang C.-H.; Tsai J. J. P.; Liu Y.-H.; Kurubanjerdjit N.; Hsieh W.-T.; Chen H.-Y.; Ng K.-L. (2015) FARE-CAFE: A Database of Functional and Regulatory Elements of Cancer-Associated Fusion Events. Database 2015, bav086. 10.1093/database/bav086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacu S.; Yuan W.; Kan Z.; Bhatt D.; Rivers C. S.; Stinson J.; Peters B. A.; Modrusan Z.; Jung K.; Seshagiri S.; Wu T. D. (2011) Deep RNA Sequencing Analysis of Readthrough Gene Fusions in Human Prostate Adenocarcinoma and Reference Samples. BMC Med. Genomics 4 (1), 11. 10.1186/1755-8794-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J.; An J.; Seim I.; Walpole C.; Hoffman A.; Moya L.; Srinivasan S.; Perry-Keene J. L.; Wang C.; Lehman M. L.; et al. (2015) Fusion Transcript Loci Share Many Genomic Features with Non-Fusion Loci. BMC Genomics 16 (1), 1021. 10.1186/s12864-015-2235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F.; Song Z.; Babiceanu M.; Song Y.; Facemire L.; Singh R.; Adli M.; Li H. (2015) Discovery of CTCF-Sensitive Cis-Spliced Fusion RNAs between Adjacent Genes in Human Prostate Cells. PLoS Genet. 11 (2), e1005001 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel-Morgenstern M.; Lacroix V.; Ezkurdia I.; Levin Y.; Gabashvili A.; Prilusky J.; del Pozo A.; Tress M.; Johnson R.; Guigo R.; Valencia A. (2012) Chimeras Taking Shape: Potential Functions of Proteins Encoded by Chimeric RNA Transcripts. Genome Res. 22 (7), 1231–1242. 10.1101/gr.130062.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingeras T. R. (2009) Implications of Chimaeric Non-Co-Linear Transcripts. Nature 461 (7261), 206–211. 10.1038/nature08452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens F.; Johansson B.; Fioretos T.; Mitelman F. (2015) The Emerging Complexity of Gene Fusions in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 15 (6), 371–381. 10.1038/nrc3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höglund M.; Frigyesi A.; Mitelman F. (2006) A Gene Fusion Network in Human Neoplasia. Oncogene 25 (18), 2674–2678. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davare M. A.; Tognon C. E. (2015) Detecting and Targetting Oncogenic Fusion Proteins in the Genomic Era. Biol. Cell 107 (5), 111–129. 10.1111/boc.201400096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stransky N.; Cerami E.; Schalm S.; Kim J. L.; Lengauer C. (2014) The Landscape of Kinase Fusions in Cancer. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–10. 10.1038/ncomms5846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helin K.; Dhanak D. (2013) Chromatin Proteins and Modifications as Drug Targets. Nature 502 (7472), 480–488. 10.1038/nature12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman F.; Johansson B.; Mertens F. (2004) Fusion Genes and Rearranged Genes as a Linear Function of Chromosome Aberrations in Cancer. Nat. Genet. 36 (4), 331–334. 10.1038/ng1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.-C.; Kannan K.; Lin S.; Yen L.; Milosavljevic A. (2013) Identification of Cancer Fusion Drivers Using Network Fusion Centrality. Bioinformatics 29 (9), 1174–1181. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shugay M.; Ortiz de Mendíbil I.; Vizmanos J. L.; Novo F. J. (2013) Oncofuse: A Computational Framework for the Prediction of the Oncogenic Potential of Gene Fusions. Bioinformatics 29 (20), 2539–2546. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abate F.; Zairis S.; Ficarra E.; Acquaviva A.; Wiggins C. H.; Frattini V.; Lasorella A.; Iavarone A.; Inghirami G.; Rabadan R. (2014) Pegasus: A Comprehensive Annotation and Prediction Tool for Detection of Driver Gene Fusions in Cancer. BMC Syst. Biol. 8 (1), 97. 10.1186/s12918-014-0097-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klijn C.; Durinck S.; Stawiski E. W.; Haverty P. M.; Jiang Z.; Liu H.; Degenhardt J.; Mayba O.; Gnad F.; Liu J.; et al. (2015) A Comprehensive Transcriptional Portrait of Human Cancer Cell Lines. Nat. Biotechnol. 33 (3), 306–312. 10.1038/nbt.3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvanathan S. P.; Graham G. T.; Erkizan H. V.; Dirksen U.; Natarajan T. G.; Dakic A.; Yu S.; Liu X.; Paulsen M. T.; Ljungman M. E.; et al. (2015) Oncogenic Fusion Protein EWS-FLI1 Is a Network Hub That Regulates Alternative Splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112 (11), E1307–E1316. 10.1073/pnas.1500536112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Zhang Z.; Li Y.; Arnovitz S.; Chen P.; Huang H.; Jiang X.; Hong G.-M.; Kunjamma R. B.; Ren H.; et al. (2013) PBX3 Is an Important Cofactor of HOXA9 in Leukemogenesis. Blood 121 (8), 1422–1431. 10.1182/blood-2012-07-442004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D.; Weinberg R. A. (2011) Hallmarks of Cancer: The next Generation. Cell 144 (5), 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-B.; Tan B.; Mu R.; Chang Y.; Wu M.; Tu H.-Q.; Zhang Y.-C.; Guo S.-S.; Qin X.-H.; Li T.; et al. (2015) Ubiquitin-Associated Domain-Containing Ubiquitin Regulatory X (UBX) Protein UBXN1 Is a Negative Regulator of Nuclear Factor ΚB (NF-ΚB) Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 290 (16), 10395–10405. 10.1074/jbc.M114.631689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G.; Mingle L.; Van De Water L.; Liu G. (2015) Control of Cell Migration through MRNA Localization and Local Translation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 6 (1), 1–15. 10.1002/wrna.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardakheh F. K.; Paul A.; Kümper S.; Sadok A.; Paterson H.; Mccarthy A.; Yuan Y.; Marshall C. J. (2015) Global Analysis of MRNA, Translation, and Protein Localization: Local Translation Is a Key Regulator of Cell Protrusions. Dev. Cell 35 (3), 344–357. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu M.; Semenova G.; Kosoff R.; Chernoff J. (2014) PAK Signalling during the Development and Progression of Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14 (1), 13–25. 10.1038/nrc3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touat M.; Ileana E.; Postel-Vinay S.; André F.; Soria J.-C. (2015) Targeting FGFR Signaling in Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 21 (12), 2684–2694. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.-M.; Su F.; Kalyana-Sundaram S.; Khazanov N.; Ateeq B.; Cao X.; Lonigro R. J.; Vats P.; Wang R.; Lin S.-F.; et al. (2013) Identification of Targetable FGFR Gene Fusions in Diverse Cancers. Cancer Discovery 3 (6), 636–647. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull I. R.; Colonna M. (2007) Activating and Inhibitory Functions of DAP12. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7 (2), 155–161. 10.1038/nri2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendramini-Costa D. B.; Carvalho J. E. (2012) Molecular Link Mechanisms between Inflammation and Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18 (26), 3831–3852. 10.2174/138161212802083707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip M.; Rowley D. A.; Schreiber H. (2004) Inflammation as a Tumor Promoter in Cancer Induction. Semin. Cancer Biol. 14 (6), 433–439. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender R. J.; Mac Gabhann F. (2013) Expression of VEGF and Semaphorin Genes Define Subgroups of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. PLoS One 8 (5), e61788 10.1371/journal.pone.0061788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skobe M.; Hawighorst T.; Jackson D. G.; Prevo R.; Janes L.; Velasco P.; Riccardi L.; Alitalo K.; Claffey K.; Detmar M. (2001) Induction of Tumor Lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C Promotes Breast Cancer Metastasis. Nat. Med. 7 (2), 192–198. 10.1038/84643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh I.; Pollastri G.; Tosatto S. C. E. (2016) Correct Machine Learning on Protein Sequences: A Peer-Reviewing Perspective. Briefings Bioinf. 17, 831. 10.1093/bib/bbv082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totoki Y.; Tatsuno K.; Yamamoto S.; Arai Y.; Hosoda F.; Ishikawa S.; Tsutsumi S.; Sonoda K.; Totsuka H.; Shirakihara T.; et al. (2011) High-Resolution Characterization of a Hepatocellular Carcinoma Genome. Nat. Genet. 43 (5), 464–469. 10.1038/ng.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagopoulos I.; Gorunova L.; Bjerkehagen B.; Lobmaier I.; Heim S. (2015) LAMTOR1-PRKCD and NUMA1-SFMBT1 Fusion Genes Identified by RNA Sequencing in Aneurysmal Benign Fibrous Histiocytoma with t(3;11)(P21;Q13). Cancer Genet. 208 (11), 545–551. 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konduri K.; Gallant J.-N.; Chae Y. K.; Giles F. J.; Gitlitz B. J.; Gowen K.; Ichihara E.; Owonikoko T. K.; Peddareddigari V.; Ramalingam S. S.; et al. (2016) EGFR Fusions as Novel Therapeutic Targets in Lung Cancer. Cancer Discovery 6 (6), 601–611. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebral K.; Schmidt H. H.; Haas O. A.; Strehl S. (2005) NUP98 Is Fused to Topoisomerase (DNA) IIbeta 180 KDa (TOP2B) in a Patient with Acute Myeloid Leukemia with a New t(3;11)(P24;P15). Clin. Cancer Res. 11 (18), 6489–6494. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyana-Sundaram S.; Shankar S.; Deroo S.; Iyer M. K.; Palanisamy N.; Chinnaiyan A. M.; Kumar-Sinha C. (2012) Gene Fusions Associated with Recurrent Amplicons Represent a Class of Passenger Aberrations in Breast Cancer. Neoplasia 14 (8), 702–708. 10.1593/neo.12914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tym J. E.; Mitsopoulos C.; Coker E. A.; Razaz P.; Schierz A. C.; Antolin A. A.; Al-Lazikani B. (2016) CanSAR: An Updated Cancer Research and Drug Discovery Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (D1), D938–D943. 10.1093/nar/gkv1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y.; Tripathi L. P.; Prathipati P.; Mizuguchi K. (2017) Network Analysis and in Silico Prediction of Protein–Protein Interactions with Applications in Drug Discovery. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 44, 134–142. 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanhaiya K.; Czeizler E.; Gratie C.; Petre I. (2017) Controlling Directed Protein Interaction Networks in Cancer. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 10327. 10.1038/s41598-017-10491-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Ivanov A. A.; Su R.; Gonzalez-Pecchi V.; Qi Q.; Liu S.; Webber P.; McMillan E.; Rusnak L.; Pham C.; et al. (2017) The OncoPPi Network of Cancer-Focused Protein-Protein Interactions to Inform Biological Insights and Therapeutic Strategies. Nat. Commun. 8, 14356. 10.1038/ncomms14356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimand J.; Wagih O.; Bader G. D. (2013) The Mutational Landscape of Phosphorylation Signaling in Cancer. Sci. Rep. 3, 2651. 10.1038/srep02651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland T.; Taşan M.; Charloteaux B.; Pevzner S. J.; Zhong Q.; Sahni N.; Yi S.; Lemmens I.; Fontanillo C.; Mosca R.; et al. (2014) A Proteome-Scale Map of the Human Interactome Network. Cell 159 (5), 1212–1226. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahni N.; Yi S.; Taipale M.; Fuxman Bass J. I.; Coulombe-Huntington J.; Yang F.; Peng J.; Weile J.; Karras G. I.; Wang Y.; et al. (2015) Widespread Macromolecular Interaction Perturbations in Human Genetic Disorders. Cell 161 (3), 647–660. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman C.; Stephens P.; Smith R.; Dalgliesh G. L.; Hunter C.; Bignell G.; Davies H.; Teague J.; Butler A.; Stevens C.; et al. (2007) Patterns of Somatic Mutation in Human Cancer Genomes. Nature 446 (7132), 153–158. 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M. S.; Stojanov P.; Polak P.; Kryukov G. V.; Cibulskis K.; Sivachenko A.; Carter S. L.; Stewart C.; Mermel C. H.; Roberts S. A.; et al. (2013) Mutational Heterogeneity in Cancer and the Search for New Cancer-Associated Genes. Nature 499 (7457), 214–218. 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway L. A.; Lander E. S. (2013) Lessons from the Cancer Genome. Cell 153 (1), 17–37. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence M. S.; Stojanov P.; Mermel C. H.; Robinson J. T.; Garraway L. A.; Golub T. R.; Meyerson M.; Gabriel S. B.; Lander E. S.; Getz G. (2014) Discovery and Saturation Analysis of Cancer Genes across 21 Tumour Types. Nature 505 (7484), 495–501. 10.1038/nature12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes S. A.; Beare D.; Gunasekaran P.; Leung K.; Bindal N.; Boutselakis H.; Ding M.; Bamford S.; Cole C.; Ward S.; et al. (2015) COSMIC: Exploring the World’s Knowledge of Somatic Mutations in Human Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (D1), D805–D811. 10.1093/nar/gku1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeger-Lotem E.; Sharan R. (2015) Human Protein Interaction Networks across Tissues and Diseases. Front. Genet. 6, 257. 10.3389/fgene.2015.00257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magger O.; Waldman Y. Y.; Ruppin E.; Sharan R. (2012) Enhancing the Prioritization of Disease-Causing Genes through Tissue Specific Protein Interaction Networks. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8 (9), e1002690 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamborero D.; Gonzalez-Perez A.; Perez-Llamas C.; Deu-Pons J.; Kandoth C.; Reimand J.; Lawrence M. S.; Getz G.; Bader G. D.; Ding L.; Lopez-Bigas N. (2013) Comprehensive Identification of Mutational Cancer Driver Genes across 12 Tumor Types. Sci. Rep. 3, 2650 10.1038/srep02650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.