Abstract

Sanquisorba officinalis has been used internally for the treatment of intestinal infections and duodenal ulcers, as well as hemorrhoids, phlebitis and varicose veins and female disorders, and topically to heal wounds, burns, and ulcers. In our study, the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, as well as quantitative analysis of polyphenols (phenolic acids, flavonoids and total polyphenols) in methanol and aqueous extracts from S. officinalis herbs are presented. A correlation between the antioxidant activity and composition of tested extracts indicates that flavonoids are the major compounds causing scavenging of free radicals. Higher content of flavonoids was found in the methanol extract, while the content of total phenolics was higher in the aqueous extract. Both extracts from S. officinalis herbs showed antioxidant activity and high antimicrobial activity in a wide spectrum of test strains.

Keywords: Sanguisorba officinalis, phenolics, flavonoids, antioxidant activity, antimicrobial activity

Introduction

Sanguisorba officinalis L. (great burnet) from the family Rosaceae is a well-known perennial plant indigenous to central and southern Europe and northern Africa, but also naturalized in North America and Asia [1, 2]. The medicinal herbs represent both aerial parts and roots. The roots of S. officinalis contain 12 – 17% tannins (mainly hydrolysable ellagitannins and gallotanins) [3], e.g., sanguisorbic acid dilactone (a trimeric gallic acid structure), and ellagitannins sanguiins H-1, H-2, and H-3 [4], galloylhamameloses I and II [5, 6], and proanthocyanidins (7-O-galloyl-(+)catechin and 3-O-galloylprocyanidin-B-3) [3, 7]. Triterpene glycosides, derivatives of the ursolic and oleanolic acids (e.g. ziyu-glycoside I and II), flavonoids, phenolic acids, disaccharide, and neolignans are also present in the roots of great burnet [1, 8–11].

The herbs of S. officinalis have been used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) for thousands of years due to hemostatic, analgesic, and astringent properties. This plant has been used internally for the treatment of chronic intestinal infections, duodenal ulcers, diarrhea, as well as hemorrhoids, phlebitis and varicose veins, and female disorders such as menorrhagia during menopause [12]. Topically, it has been also applied to heal wounds, burns, and ulcers, and to treat bleeding, e.g., nosebleeds [2].

Previous studies confirmed that ethanol and aqueous extracts of the aerial parts and roots of S. officinalis possess numerous pharmacological activities. The ethanol extract in in vitro studies exhibits anti-inflammatory properties and can therefore be effective against bronchial asthma associated with allergic diseases [13]. The aqueous extract and disaccharides isolated from S. officinalis roots inhibited immediate- type allergic reactions [9, 14]. The mechanism of the anti-inflammatory activity of S. officinalis roots was related to blocking the production of NO and PGE2 on transcriptional levels [12]. The methanol extract of great burnet showed a protective effect against carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity in rats [15]. An immunomodulatory effect of the polysaccharide fraction of S. officinalis extract was also demonstrated [10, 16]. Triterpene glycosides displayed antioxidant properties, including suppression of lipid peroxide and hydroxyl radical generation and upregulation of the superoxide dismutase activity [17]. Terpene glycosides exhibited hemostatic activity, the strongest one being shown by ziyu-glycoside I [18]. The aqueous extract of S. officinalis showed neuroprotective effects on the transient focal ischemia in rats, and the methanol extract also exhibited neuroprotective effect on the oxidative stress induced by amyloid beta protein [19–21]. The S. officinalis extracts demonstrated a great antithrombin effect and exhibited inhibitory activity against murine leukemia cells [13, 22]. Gallocatechin isolated from the roots showed a significant impact on tacrine induced cytotoxicity in Hep G2 cells [23]. Some of the triterpene glycosides from the roots were found to be cytotoxic against human oral squamous cell carcinoma (HSC-2) cells and human stomach tumor cells [8]. The ziyu-glucoside II showed an anticancer effect on the human gastric carcinoma BGC-823 cells [24], and an antiproliferative effect on human breast tumor cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB 231 [25]. The methanol extract of S. officinalis inhibited the growth of prostate cancer cell PC 3 and induced apoptotic cell death by downregulation of McI-1 protein expression and Bax oligomerization [18]. The aqueous extract of S. officinalis turned out to be effective in in vitro inhibition of the hepatitis B virus DNA polymerase activity and suppressed the hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) [26, 27]. The methanol extract of S. officinalis radix reduced coronavirus (CoV) replication [28]. The ethanol extract from the aerial part and rhizome of S. officinalis showed antibacterial activity [29]. The S. officinalis extract inhibited endothelin- 1 production in human keratinocytes, which plays an important role in UV-B induced pigmentation and fibroblastderived elastase, hence influencing the formation of wrinkles induced by UV-B [30, 31]. Ziyu-glycoside I was shown to be responsible for this activity [32]. Currently, both roots and aerial parts of great burnet are used in cosmetology. The S. officinalis root extract is classified as cleansing, refreshing, skin conditioning and tonic agent [33].

The purpose of this study was to analyze the effect of the extraction solvent type on the amount of extracted phenolic acids, flavonoids, and total phenolics, as well as on the antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of S. officinalis herb extracts.

Experimental Part

Plant Material

Commercial samples of S. officinalis herbs were used for this study (Dary Natury Miros3aw Angielczyk, Koryciny 73, Grodzisk). They had been purchased in one of the pharmacies in Poznañ in 2013.

Chemicals

Acetone, methanol, ethyl acetate, hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide, sodium carbonate, sodium molybdate, and sodium nitrite were obtained from POCh (Gliwice, Poland). Caffeic and gallic acids were purchased from Carl Roth GmbH Co., Germany; Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and aluminum chloride were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany), dimethylosulfoxide (DMSO) from Ubichem Ltd. (Hampshire, England), p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet (INT) dye and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical from Sigma-Aldrich (United States), and butylhydroxyanisole (BHA) from Fluka (France). The absorbance was measured using a Lambda 35 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer, United States).

Preparation of Extracts

Dried and powdered herbs of great burnet were extracted twice with methanol (10.0 g raw material and 30 mL solvent treated for 30 min in ultrasonic bath at 50°C) or once with water (10.0 g raw material with 200 mL boiling water added and left to stay for 30 min after being covered). The extracts were filtered through a Whatman no. 1 filter and the filtrates were concentrated to dryness. The quantitative analyses and antioxidant studies were conducted for stock solutions, which were prepared from the dry extracts diluted with water to 50 mL to obtain MeOH extract (I) and H2O extract (II). For antimicrobial testing, 1% (w/v) stock solutions of both extracts were prepared in pure DMSO.

Determination of Phenolic Acids (TPAC)

The total content of phenolic acids (TPAC) was determined by a spectrophotometric method with Arnov’s reagent (10.0 g sodium molybdate, 10.0 g sodium nitrite in 100.0 mL water) as described in Polish Pharmacopoeia VI [34]. An aliquot (1 mL) of the stock solution of extract I or II was mixed with 5 mL water, 1.0 mL HCl (18 g/L), 1.0 mL Arnov’s reagent, and 1.0 mL NaOH (40 g/L) and diluted to 10.0 mL with water. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm against a blank. The TPAC, expressed as percentage of caffeic acid (% CA), was calculated according to the following formula: TPAC (%) = A × 0.877/m, where A is the absorbance of the sample solution and m is the mass (expressed in grams) of the dry herbal material.

Determination of Flavonoids (TFC)

The total content of flavonoids (TFC) was determined spectrophotometrically according to the procedure described in European Pharmacopoeia VIII [35] with slight modifications. The absorbance of yellow complexes between aluminum chloride and carbonyl and hydroxyl groups of the flavonoids in the extracts was measured spectrophotometrically at 425 nm. The TFC, expressed as percentage of quercetin (% Q), was calculated using the following formula: TFC (%) = A × 0.875/m, where A is the absorbance of the sample solution and m is the mass (expressed in grams) of the dry herbal material.

Determination of Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC)

The total content of phenolic compounds (TPC) in the extracts was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent [36]. Briefly, 0.2 mL of extracts I or II was put into a 10.0 mL volumetric flask containing 4.0 mL water; then, 0.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent and, in 1 min, 2.0 mL of 20% aqueous solution of sodium carbonate were added. The mixture was diluted to 10.0 mL with distilled water and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 760 nm. A mixture of 0.5 mL Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent, 2.0 mL 20% aqueous solution of sodium carbonate diluted to 10.0 mL with water was used as a blank. The TPC was calculated using a calibration curve (y = 13.37542x; R 2 = 0.9991) constructed using gallic acid (within 0.001 – 0.006 mg/mL) as a standard. The results were expressed as percentage of gallic acid (% GA).

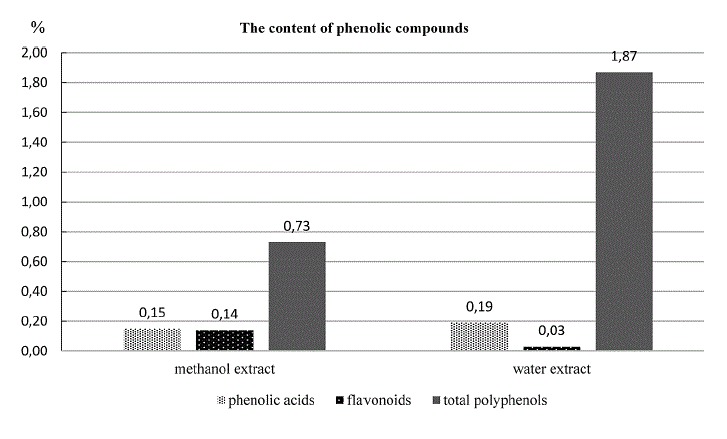

Data on the TPAC, TFC, and TPC in extracts I and II are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Table 1.

The content of phenolic acids (TPAC), flavonoids (TFC) and total phenolic compounds (TPC) and the ratio of TPAC, TFC to TPC in different extracts (I – MeOH; II – H2O) from S. officinalis herb, n = 6

| Content (%) | Extract | |

|---|---|---|

| I | II | |

| TPAC (% CA) | 0.153 ± 0.004 | 0.193 ± 0.001 |

| TFC (% Q) | 0.030 ± 0.001 | 0.143 ± 0.004 |

| TPC (% GA) | 1.871 ± 0.029 | 0.726 ± 0.007 |

| Ratio (%) | I | II |

| TPAC / TPC | 21.1 | 10.3 |

| TFC / TPC | 19.9 | 1.6 |

| (TPAC + TFC) / TPC | 42.0 | 11.9 |

CA – caffeic acid, Q – quercetin, GA – galic acid

Fig. 1.

The content of phenolic acids, flavonoids and total phenolic compounds in methanol (I) and water (II) extracts from S. officinalis herb.

Antioxidant Activity

The free radical scavenging capacity of the samples was determined using the DPPH method [37–39]. For this purpose, an aliquot (200 μL) of extract I or II was dissolved in water to various concentrations (0.5 – 20.0 mg/mL) and mixed with 1.4 mL DPPH solution (0.0062 g/100 mL MeOH). After 30 min incubation in darkness at room temperature, the absorbance (A) was measured at 517 nm against a blank.

The free radical activity was calculated as percentage inhibition using the following formula:

where A blank is the absorbance of the control solution (containing all reagents except the tested extracts) and A sample is the absorbance of the sample. The results were also expressed in terms of the IC50 parameter defined as the concentration of antioxidant that causes 50% DPPH loss in the DPPH radical scavenging activity test. The IC50 values were determined by linear regression. BHA solution (0.01 – 1.00 mg/mL) was used as the positive control. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) of methanol (I) and water extract (II) from the herb of S. officinalis and BHA

| Concentration (mg/ml) | DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| methanol extract (I) | water extract (II) | BHA | |

| 0.01 | – | – | 3.26 ± 0.31 |

| 0.05 | – | – | 21.42 ± 0.30 |

| 0.10 | – | – | 27.18 ± 0.36 |

| 0.25 | – | – | 55.70 ± 0.42 |

| 0.50 | 9.45 ± 0.38 | 9.07 ± 1.13 | 60.60 ± 0.27 |

| 1.00 | 18.73 ± 0.51 | 26.97 ± 0.17 | 65.23 ± 0.56 |

| 2.00 | 28.12 ± 0.62 | 42.27 ± 0.46 | – |

| 5.00 | 61.27 ± 0.31 | 61.20 ± 0.46 | – |

| 10.00 | 68.53 ± 0.16 | 63.79 ± 0.31 | – |

| 20.00 | 71.88 ± 0.37 | 65.49 ± 0.47 | – |

| IC50 (mg/ml) | 2.95 | 3.65 | 0.20 |

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained in this study were expressed as the mean of six replicate, plus or minus the confidence interval. The differences were considered significant for p ≤ 0.05. Correlation between the antioxidant capacity and TPC was analyzed using the simple linear regression, and the coefficient of determination (R 2) was calculated. The statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2007 software.

Antimicrobial Activity

A series of diluted extracts with concentrations ranging from 0.07 to 2.50 mg mL-1 were studied. The test organisms used in this study were as follows: Gram-positive strains Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 953825923, Staphylococcus epidermidis NCTS 11047, Microccocus luteus ATCC 9341, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 14428; Gram-negative strains Escherichia coli ATCC 8196, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 27736, Psedomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853; and fungal strain Candida albicans ATCC 10231.

The test strains were maintained and tested on the Mueller-Hinton broth (bacteria) and Sabouraud chloramphenicol broth (mycetes) media purchased from Bio-Merieux (France). Twenty-hour cultures of the reference strains of bacteria and fungi were diluted 1 : 1 according to the McFarland scale (i.e., 0.5) in a sterile normal saline solution at a concentration of 106 CFU/mL.

An aliquot (1 mL) of a suspension of the reference microbe strain was added to each concentration of the extracts and diluted in the liquid medium. Then the mixture was incubated at 35 – 37°C (bacteria) or 25°C (fungi) for 24 h and examined. A clear medium indicated inhibition of the micro-organism growth, while turbidity development or precipitate formation in the medium confirmed its growth.

When turbidity appeared after dilution of the plant extract fraction in the liquid medium, some amount of the aqueous solution of INT at a concentration of 2 mg/mL was added. After incubation, the growth of micro-organisms was evidenced by red colour appearance in the sample. Following this procedure, the lowest concentration of the extract inhibiting the visible growth of each micro-organism (denoted as MIC) was determined (Table 3).

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity of tested extracts from the herb and root of Sanquisorba officinalis and gentamicin and nystatin

| Microorganisms | MIC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (mg ml–1) | (μg ml–1) | ||

| methanol | water | gentamicin | |

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||

| Staphylococcs aureus | 0.07 | 0.15 | 2.0 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.0 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 2.50 | 2.50 | 32.0 |

| Micrococcus luteus | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.0 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 0.07 | 0.07 | 8.0 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | |||

| Escherichia coli | 0.30 | 0.30 | 2.0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 0.30 | 0.30 | 2.0 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 0.30 | 0.30 | 20.0 |

| Fungi | nystatin | ||

| Candida albicans | 0.60 | 0.60 | 16.0 |

Tests with DMSO used as a negative control and gentamycin for the bacteria or nystatin for the fungi as a positive control were carried out in parallel. All tests were performed in duplicate and the antibacterial activity was expressed as the mean value.

Results and Discussion

In this study, the content of phenolic acids, flavonoids, and total phenolics in methanol and aqueous extracts from S. officinalis herbs was investigated. The content of phenolic acids and flavonoids was determined by the colorimetric methods recommended by the FP VI [34] and Ph. Eur. VIII [35]. The total phenolics content was determined by the analysis with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent [36]. The results of these determinations are presented in Table 1 and graphically illustrated in Fig. 1. Table 1 gives the TPAC/TPC and TFC/TPC ratios, as well as the ratio of the TPAC+TFC sum to TPC.

Phenolic acids are present in the herb of great burnet in low amounts. No considerable differences in TPC between the studied extracts were observed. The results also showed that phenolic acids constituted about 10% of total polyphenols in the aqueous extract and about 20% in the methanol extract.

The content of flavonoids was about three times greater in the methanol extract than in the aqueous extract (0.143% and 0.030%, respectively, expressed as quercetin). The study showed that flavonoids constituted about 20% of total polyphenols in the methanol extract and only 1.6% in the aqueous extract.

The concentration of total phenolic compounds in extracts also depends on the type of extractant. The highest level of phenolics was found in the aqueous extract (1.871% expressed as gallic acid), while the lowest content (about 2.5 times as small) was observed in the methanol extract from S. officinalis herbs.

In the methanol extract, the content of the sum of phenolic acids and flavonoids constituted 42% of the total polyphenols, whereas in the aqueous extract it amounted to about 12%. These results suggest the presence of some groups of compounds (e.g., tannins) other than phenolic acids and flavonoids in the aqueous extract [3, 6].

The antioxidant activity of the tested extracts, expressed as the ability to scavenge DPPH free radicals (percentage of the DPPH decrease) and the IC50 parameter defined as the concentration of the extract that scavenges 50 % of the DPPH free radical, have been shown in Table 2.

The antioxidant activity of S. officinalis extracts increased with the amount of extracted raw plant material. Greater activity was shown by the methanol extract (IC50 = 2.95 mg/mL), while the aqueous extract had a slightly weaker ability to scavenge free radicals (IC50 = 3.65 mg/mL); however, IC50 of the BHA solution (used as a standard antioxidant) was 0.20 mg/mL.

The TFC in the methanol extract was 5 times higher than in the aqueous extract. This, rather than the TPC which was greater in H2O extract, most likely explains the higher antioxidant activity of the methanol extract (IC50 = 2.95 mg/mL) as compared to the aqueous extract (IC50 = 3.65 mg/mL).

In our study, a positive correlation was observed between the antioxidant activity and total flavonoid content, while there was inverse correlation between the antioxidant activity and TPC. A correlation between the antioxidant activity and TFC was also demonstrated in the case of alcohol and aqueous extracts from the aerial parts of S. minor [40]. In previous studies carried out with aqueous extracts, (+)-gallocatechin and methyl 6-O-galloyl-β-glucopyranoside isolated from the roots of S. officinalis showed high antioxidant activity (1940 μmol Trolox equivalent/g dry extract) [23, 41].

The antimicrobial activity was studied on standard strains of five Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus, S. epidermidis, M. luteus, B. subtilis, E. faecalis), three Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa), and fungi (C. albicans). All herbal extracts showed antimicrobial activity with MIC = 0.07 – 2.50 mg/mL. The MIC values obtained are listed in Table 3. The methanol and aqueous extracts from S. officinalis herbs revealed a high bacteriostatic activity against all Gram-positive bacteria (except for E. faecalis) and against Gram-negative bacteria (K. pneumoniae, E. coli, P. aeruginosa). The analyzed extracts were moderately active against C. albicans. Gentamycin used as a positive control showed MIC within 1 – 32 μg/mL against Gram-positive and MIC = 2 μg/mL against Gram-negative bacteria; MIC of nystatin against C. albicans ranged from 16 to 32 μg/mL.

Conclusion

In the study dependence activities and the type of extracts of the S. officinalis herb were presented. Studies of correlation between the antioxidant activity and extracted compounds indicated that flavonoids were the major compounds producing scavenging of free radicals, since the content of flavonoids found in the methanol extract was higher than that in the aqueous extract.

The results presented above indicate a wide spectrum and high antimicrobial activity of both methanol and aqueous extracts obtained from S. officinalis herbs. The established antimicrobial activity, in particular inhibition of the growth of micro-organisms causing inflammation of the skin and mucous membrane, fully justifies the use of S. officinalis in traditional medicine.

References

- 1.Liu X, Cui Y, Yu Q, Yu B. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1671–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gruenwald J, Brendler T, Jaenicke MD. PDR for Herbal Medicines. 3. Montvale, NJ: Thomson PDR; 2004. pp. 404–405. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popov IV, Andreeva IN, Gavrilin MV. Pharm. Chem. J. 2003;37:360–363. doi: 10.1023/A:1026319524715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nonaka G, Tanaka T, Nishioka I, Chem J. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1982;1:1067–1073. doi: 10.1039/p19820001067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka T, Nonaka G, Nishioka I. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1984;32:117–121. doi: 10.1248/cpb.32.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nonaka G, Ishimaru K, Tanaka T, Nishioka I. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1984;32:483–489. doi: 10.1248/cpb.32.483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka T, Nonaka G, Nishioka I. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:2575–2578. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(83)80168-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mimaki Y, Fukushima M, Yokosuka A, et al. Phytochemistry. 2001;57:773–779. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.K. H. Park, D. Koh., K. Kim, et al., Phytother. Res.,18, 658 – 662 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Zhang S, Liu X, Zhang ZL, et al. Molecules. 2012;17:13917–13922. doi: 10.3390/molecules171213917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu J, Shi XD, Chen JG, Li CS, Asian Nat J. Prod. Res. 2012;14:171–175. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2011.634803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu T, Lee YJ, Yang HM, et al. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee NH, Lee MY, Lee JA, et al. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2010;26:201–208. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.T. Y. Shin, K. B Lee, and S. H. Kim, Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol., 24, 455 – 68 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Jeong CS, Suh IO, Hyun JE, Lee EB. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2003;9:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai Z, Li W, Wang H, et al. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012;51:484–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.J. Choi, M. Y. Kim, B. C Cha, et al., Planta Med.,78, 12 – 17 (2012).

- 18.Sun W, Zhang ZL, Liu X, et al. Molecules. 2012;25:7629–7636. doi: 10.3390/molecules17077629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh JK, Jung JW, Ahn NY, et al. Korean J. Pharmacogn. 2003;34:335–338. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ban JY, Nguyen HTT, Lee HJ, et al. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008;31:149–153. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen TT, Cho SO, Ban JY, et al. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008;31:2028–2035. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goun EA, Petrichenko VM, Solodnikov SU, et al. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002;81:337–342. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.An RB, Tian YH, Oh H, Kim YC. Nat. Prod. Sci. 2005;11:119–122. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu AK, Zhou H, Xia JZ, et al. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2013;46:670–675. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20133050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu X, Wang K, Zhang K, et al. Toxicol. Lett. 2014;16:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.T. H. C. Chung, Y. Kim, M. K, C. Moon, et al., Phytother. Res.,11, 179 – 182 (1997).

- 27.Kim TG, Kang SY, Jung KK, et al. Phytother. Res. 2001;15:718–720. doi: 10.1002/ptr.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HY, Eo EY, Park H, et al. Antivir. Ther. 2010;15:697–709. doi: 10.3851/IMP1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kokoska L, Polesny Z, Rada V, et al. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82:51–53. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hachiya A, Kobayashi A, Ohuchi A, et al. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2001;24:688–692. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsukahara K, Moriwaki S, Fujimura T, Takema Y. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2001;24:998–1003. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim YH, Chung CB, Kim JG, et al. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008;72:303–11. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.http: // www.ec.europa.eu, International Nomenclature of Cosmetic Ingredients (INCI).

- 34.Polish Pharmacopoeia VI, Polish Pharmaceutical Society, Warszawa, Poland (2002).

- 35.European Pharmacopoeia VIII. Council of Europe. European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines. Strasbourg, Council of Europe (2014).

- 36.Djeridane A, Yousfi M, Nadjemi B, et al. Food Chem. 2006;97:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.04.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A. Gawron-Gzella, M. Dudek-Makuch, and I. Mat3awska, Acta Biol. Cracoviensia Ser. Botanica, 54, 32 – 38 (2012).

- 38.Assimopoulou AN, Sinakos Z, Papageorgiou VP. Phytother. Res. 2005;19:997–1000. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molyneux P. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2004;25:211–219. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferreira AC, Proenc C, Serralheiro MLM, Araujo MEM. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;108:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao H, Banbury LK, Leach DN. Evid. Based Complem. Altern. Med. 2008;5:429–434. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]