Abstract

A divergent rotavirus I was detected using viral metagenomics in the feces of a cat with diarrhea. The eleven segments of rotavirus I strain Felis catus encoded non-structural and structural proteins with amino acid identities ranging from 25 to 79% to the only two currently sequenced members of that viral species both derived from canine feces. No other eukaryotic viral sequences nor bacterial and protozoan pathogens were detected in this fecal sample suggesting the involvement of rotavirus I in feline diarrhea.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11262-017-1440-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Rotavirus, Feces, Diarrhea, Cat, Metagenomics

Introduction

Rotaviruses (RVs) are important enteric pathogens causing gastroenteritis in many mammals and birds [1–3]. RVs, in the family Reoviridae, with double-stranded RNA genomes of 11 segment encoding six structural proteins (VP1-4, VP6, and VP7), and at least five non-structural proteins (NSP1-5) [4]. RVs are classified into eight different species A-H [5, 6]. A new rotavirus species I was recently found in feces of two sheltered dogs in Hungary using deep sequencing [7]. One suckling dog was clinically asymptomatic, while the adult dog had diarrhea [7].

Materials and methods

Viral metagenomics was used to analyze three fecal specimens collected from cats from North America with diarrhea of undetermined etiology. A pool of three fecal specimens was clarified by 15,000×g centrifugation for ten minutes, and then filtered through a 0.45-µm filter (Millipore). The filtrates were treated with a mixture of nuclease enzymes of 14U turbo DNase (Ambion), 3U Baseline-ZERO (Epicenter), and 20U RNase One (Promega) in 1 × DNase buffer (Ambion) at 37 °C for 1.5 h to digest unprotected nucleic acids. Viral nucleic acids were then extracted using a MagMAX Viral RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion). Reverse transcription into cDNA used a primer containing a fixed 18-bp sequence plus a random nonamer at the 3′ end (GCCGACTAATGCGTAGTCNNNNNNNNN) [8]. The 2nd strand DNA was generated using Klenow Fragment (New England Biolabs). PCR was performed using the fixed 18-bp portion (GCCGACTAATGCGTAGTC) [8]. The resulting dsDNA products were used to construct a DNA library with the Nextera XT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) [9]. The library was sequenced using the HiSeq Illumina platform with 150 bases paired ends. An in-house analytical pipeline running on a 36-node Linux cluster was used to analyze sequence data. Raw data are first pre-processed by subtracting duplicate sequences and low-quality reads. The cleaned reads are de novo assembled using the ENSEMBLE assembler [10]. Viral sequences were identified through translated protein sequence similarity search (BLASTx) to annotated viral proteins available in GenBank’s viral database. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using CLUSTAL X [11]. Sequence identity was determined using BioEdit. Phylogenetic trees with bootstrap resampling of the alignment datasets were generated using the maximum likelihood method and visualized using the program MEGA version 6 [12].

Results

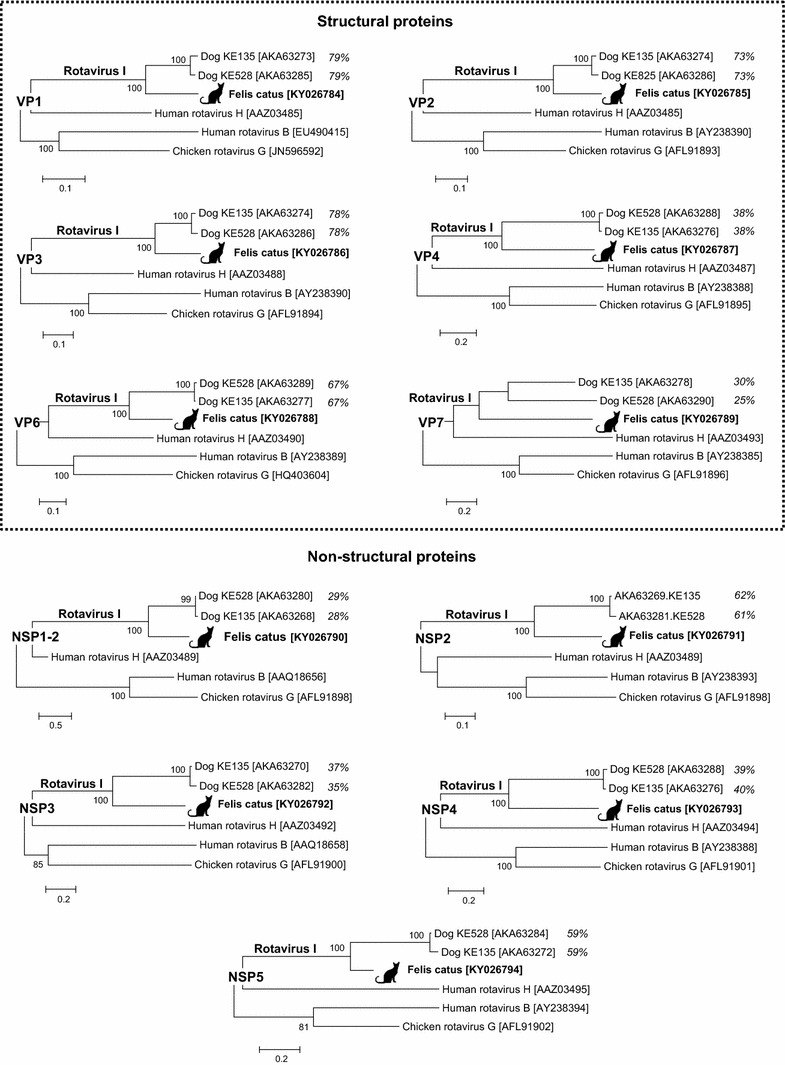

5,015,275 unique sequence reads were generated from the fecal pool. Using BLASTx, twelve sequence reads related to rotavirus (E scores <3.5 × 10−6) were found. Total nucleic acids of individual specimens within that pool were extracted, and one individual specimen containing the rotavirus RNA was identified by RT-PCR. The diarrheic animal was a 7-month old, in-house only, domestic short hair with no dog contact sampled in Canada in 2016. This animal had tested negative for the following bacteria: Campylobacter coli, Campylobacter jejuni, Salmonella spp, and Clostridium perfringens alpha toxin gene; viruses: feline coronavirus and feline panleukopenia virus, and protozoans: Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia spp., Toxoplasma gondii, and Tritrichomonas foetus (IDEXX Laboratories, Inc., diarrhea RealPCR™ panel comprehensive, test code 2627). In order to test for the presence of other viruses, the rotavirus positive specimen was then individually deep sequenced using the same metagenomics strategy described in the materials and methods. Out of 1,660,059 unique sequence reads generated from the rotavirus positive specimen, there were a total of 32,407 rotavirus reads (Supplemental Table 1). De novo assembly using the ENSEMBLE assembler [10] successfully acquired 17,234 nucleotides of the divergent rotavirus I strain Felis catus, encoding the complete proteins of all 11 genome segments (GenBank KY026784-KY026794) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Its VP1-4, VP6, and VP7 proteins showed best hits to rotavirus strains KE135 and KE528, the only two sequenced members in the newly proposed rotavirus species I [7], sharing 27–79% identities at the amino acid level (Fig. 1). The VP7 protein of rotavirus I strain Felis catus had five conserved cysteine residues required for protein structure stabilization. Similar to rotavirus species A and C, the VP7 also contained the motif 121NST123 glycosylation site [13], which was not found in the other two species I rotaviruses. Like rotavirus species I, the NSP1 gene had two ORFs encoding a minor peptide and a major peptide labeled as NSP1-1 (80-aa) and NSP1-2 (424-aa), respectively. While the NSP1-1 did not show any significant similarities in GenBank, the NSP1-2 shared the closest match to KE135 with 28% amino acid identity and KE528 with 29% amino acid identity (Fig. 1). Similarly, the four non-structural proteins (NSP2-5) had the greatest amino acid sequence hits (37–62%) to homologous proteins from canine rotavirus I KE135 and KE528. The NSP2 possessed a conserved motif HGXGHXRXV [321HGRKHIRSV329] located at the RNA-binding domain [14]. Phylogenetic analyses also showed that rotavirus I strain Felis catus shared a monophyletic root, being most closely related to the two currently known rotavirus species I strains both from dogs (Fig. 1). The strain was named RVI/Cat-wt/CAN/Felis catus/2016/G3P2 according to recent guidelines [15].

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analyses. Phylogenetic trees were generated using six structural (VP1-4, VP6, and VP7) and five non-structural proteins (NSP1-5) of the rotavirus I strain Felis catus, the two species I strains (KE135 and KE528), and representatives of other species in the Rotavirus genus. The scale indicates amino acid substitutions per position. Bootstrap values (based on 100 replicates) for each node are given if >70. The amino acid identity (%) between rotavirus I strain Felis catus and KE135 or KE528 are included in the trees

Discussion

Members of a rotavirus species share >53% amino acid identity in VP6 [15]. The pair-wise comparison revealed that the sequence of the VP6-encoding genome segment had 67% amino acid identity to rotavirus species I. Therefore, rotavirus I strain Felis catus is the third sequenced rotavirus genome from species I, and the first from a species other than dog.

No other eukaryotic viral sequences nor bacterial or protozoan pathogens were detected in the individually sequenced fecal sample. A causative role of this rotavirus strain for this cat’s diarrhea is therefore possible, but further studies will be required to determine the pathogenicity and epidemiology of rotavirus I in cats and dogs.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge support from IDEXX Laboratories, Inc.

Author contributions

TP, CL, and ED: designed the study; TP and CL: performed experiments; TP, CL, and ED: wrote the manuscript; and CL and RC: provided clinical information and samples.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Martella V, Banyai K, Matthijnssens J, Buonavoglia C, Ciarlet M. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;140:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein DI. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2009;28:S50–S53. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181967bee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhama K, Saminathan M, Karthik K, Tiwari R, Shabbir MZ, Kumar N, Malik YS, Singh RK. Vet. Q. 2015;35:142–158. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2015.1046014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desselberger U. Virus Res. 2014;190:75–96. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kindler E, Trojnar E, Heckel G, Otto PH, Johne R. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2013;14:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trojnar E, Otto P, Roth B, Reetz J, Johne R. J. Virol. 2010;84:10254–10265. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00332-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mihalov-Kovacs E, Gellert A, Marton S, Farkas SL, Feher E, Oldal M, Jakab F, Martella V, Banyai K. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:660–663. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Deng X, Mee ET, Collot-Teixeira S, Anderson R, Schepelmann S, Minor PD, Delwart E. J. Virol. Methods. 2015;213:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan TG, Mori D, Deng X, Rajindrajith S, Ranawaka U, Fan Ng TF, Bucardo-Rivera F, Orlandi P, Ahmed K, Delwart E. Virology. 2015;482:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng X, Naccache SN, Ng T, Federman S, Li L, Chiu CY, Delwart EL. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e46. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saitou N, Nei M. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arias CF, Lopez S, Bell JR, Strauss JH. J. Virol. 1984;50:657–661. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.2.657-661.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar M, Jayaram H, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Jiang X, Taraporewala ZF, Jacobson RH, Patton JT, Prasad BV. J. Virol. 2007;81:12272–12284. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00984-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthijnssens J, Otto PH, Ciarlet M, Desselberger U, Van Ranst M, Johne R. Arch. Virol. 2012;157:1177–1182. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.