Abstract

Infections by type II feline coronaviruses (FCoVs) have been shown to be significantly correlated with fatal feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). Despite nearly six decades having passed since its first emergence, different studies have shown that type II FCoV represents only a small portion of the total FCoV seropositivity in cats; hence, there is very limited knowledge of the evolution of type II FCoV. To elucidate the correlation between viral emergence and FIP, a local isolate (NTU156) that was derived from a FIP cat was analyzed along with other worldwide strains. Containing an in-frame deletion of 442 nucleotides in open reading frame 3c, the complete genome size of NTU156 (28,897 nucleotides) appears to be the smallest among the known type II feline coronaviruses. Bootscan analysis revealed that NTU156 evolved from two crossover events between type I FCoV and canine coronavirus, with recombination sites located in the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and M genes. With an exchange of nearly one-third of the genome with other members of alphacoronaviruses, the new emerging virus could gain new antigenicity, posing a threat to cats that either have been infected with a type I virus before or never have been infected with FCoV.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11262-012-0864-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Type II feline coronavirus, Feline infectious peritonitis, Genome analysis, Virus recombination, Virus evolution

Introduction

Feline coronaviruses (FCoVs) are large, enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses with a genome of approximately 29,200 nucleotides [1–3]. The FCoVs belong to the genus Alphacoronavirus, family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales. Other members of this subgroup include canine coronavirus (CCoV), transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), raccoon dog CoV (RDCoV/GZ43/03), and Chinese ferret badger CoV (CFBCoV/DM95/03) [4].

FCoVs are associated with diseases that range from subclinical and/or mild enteric infections to fatal infectious peritonitis [5]. Despite the high prevalence of FCoVs in feline populations around the world, only 5–12 % of seropositive cats develop feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). FIP is a chronic, progressive, immune-mediated disease in domestic and nondomestic fields. The typical histopathological finding of this disease is systemic perivascular necrotizing pyogranulomatous inflammation [6]. Two serotypes that differ in their growth characteristics in tissue culture and in their genetic relationship to CCoV and TGEV have been identified [7, 8]. Type II FCoV is significantly correlated with FIP when compared to type I viruses [9, 10]. However, unlike the ubiquity of type I FCoV, infection by type II virus encompasses only a small percentage of the total number of FCoV-seropositive cats in different studies [9–16].

Type II FCoV is estimated to have diverged from alphacoronavirues in 1953 [4]. Based on partial genomic sequence analysis, type II FCoVs were suggested to result from a double recombination between type I FCoV and CCoV [17]. Like most RNA viruses, CoVs mutate at a high frequency due to the high error rate of RNA polymerization. In addition, a unique feature of CoV genetics is the high frequency of RNA recombination in the natural evolution of this virus [18]. Recombination among CoVs is an attribute of the genus and is thought to contribute to the emergence of new pathotypes, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome CoV [19, 20], human CoV NL63 (HCoV NL63) [21], HCoV HKU1 [22], and avian infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) [23–26]. To gain better evolutionary insight into type II FCoVs, we analyzed the complete genome of a novel type II FCoV isolate. Taking our data together with data from other strains, we discuss the evolution of type II FCoV.

Materials and methods

Virus and isolation of viral RNA

FCoV NTU156 was isolated in 2007 from a kitten with naturally occurring FIP by the co-cultivation of pleural effusion with feline fcwf-4 cells [27]. After three rounds of purification by limited dilution, the virus was propagated and titrated. All of the viruses used in this study for the sequencing of complete genome came from a stock virus passaged six times. NTU156 is relatively fast-growing, induces a coronavirus-typical syncytial cytopathic effect and is a type II FCoV [10].

Reverse transcription and PCR amplification of viral sequences

Eleven microliters of isolated RNA was added to the premix, consisting of 4 μl of 5× RT buffer, 2.5 mmol dNTPs (GeneTeks Bioscience, Inc., Taipei), 50 pmol random primer, 0.2 mol dithiothreitol, and 1 μl of 200 U Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, CA, USA) in a 0.6 ml reaction tube. This reaction mixture was then briefly centrifuged and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, then at 72 °C for 15 min, and finally at 94 °C for 5 min. A total of 120 primers for PCR were chosen from a relatively conserved region of the FCoV genome. Following reverse transcription, 1 μl of the RT reaction mixture was added to 49 μl of the PCR mixture, which consisted of 5 μl of 10× Taq buffer, each primer (10 pmol), dNTP (2.5 mmol), 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (GeneTeks, BioScience, Inc., Taipei), and 39 μl of 0.1 % DEPC water. An ABI-2720 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA) consisted of 3 min of preheating at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The viral RNA termini were amplified using 3′- and 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (Invitrogen, USA).

Analysis of PCR-amplified products and sequencing

A total of 10 μl of PCR products from each PCR mixture was analyzed using a 1 % agarose gel (Viogene, Taipei) for electrophoresis. Amplification products were visualized using UV illumination after ethidium bromide staining. The nucleotide sequences of the targeted DNA fragments were purified (Geneaid Biotech, Taipei) and sequenced in both directions using an auto sequencer (ABI 3730XL, USA). Full-length genome sequencing of NTU156 was performed by single-round PCR with a set of overlapping PCR products (average size 750 bp) that encompassed the entire genome.

Sequence analysis

The complete sequences of NTU156 were then compared with other alphacoronaviruses and the results are summarized in Table 1. Multiple alignments of nucleic acid sequences were performed by the Clustal W method using the MegAlign program (DNASTAR Inc., WI, USA). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using MEGA, version 4.0. Similarity graphs were prepared with SimPlot 2.5 software [28]. Potential recombination sites were identified using the Recombination Detection Program (RDP) [29].

Table 1.

Isolation dates and accession numbers of NTU156 and other alphacoronavirses

| Isolation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Host | Year | Country | References | GenBank accession no. |

| FCoV NTU156a | Cat | 2007 | Taiwan | Lin [10] | GQ152141 |

| FCoV NTU2 | Cat | 2003 | Taiwan | Unpublished | DQ160294 |

| FCoV 79-1146a | Cat | 1979 | USA | McKeirnan (1981) | DQ010921 |

| FCoV Blacka | Cat | 1980 | USA | Black (1980) | EU186072 |

| FCoV UU2a | Cat | 1993 | USA | Unpublished | FJ938060 |

| FCoV DF-2a | Cat | 1981 | USA | Everman (1981) | JQ408981 |

| FCoV C1Jea | Cat | 2007 | UK | Dye [2] | DQ848678 |

| FCoV 79-1683a | Cat | 1979 | USA | McKeirnan (1981) | JN634064 |

| FCoV KU-2 | Cat | 1991 | Japan | Hohdatsu (1991) | D32044 |

| FCoV Yayoi | Cat | 1981 | Japan | Hayashi (1981) | AB695067 |

| FCoV C3663 | Cat | 1994 | Japan | Mochizuki (1997) | AB535528 |

| CCoV NTU336a | Dog | 2008 | Taiwan | Unpublished | GQ477367 |

| CCoV 1-71a | Dog | 1971 | Germany | Binn (1974) | JQ404409 |

| CCoV TN-449a | Dog | 1980s | USA | Unpublished | JQ404410 |

| CCoV 174/06 | Dog | 2006 | Italy | Decaro (2009) | EU856362 |

| TGEV Purduea | Pig | 1946 | USA | Doyle (1946) | DQ811789 |

| TGEV M6a | Pig | 1965 | USA | Bohl (1965) | DQ811785 |

| TGEV TSa | Pig | 2004 | China | Cheng (2004) | DQ201447 |

| HCoV 229Ea | Human | 1963 | Hamre (1966) | AF304460 | |

aFull genome available

Results

Genomic sequence of FCoV NTU156

The full genomic RNA sequence of FCoV NTU156 comprises 28,897 nucleotides (nts), excluding the 3′ polyadenylated nts. Sequence analysis revealed that NTU156 contains conserved open reading frames with an overall genome organization similar to known FCoVs (Table 2). The overall nucleotide composition is as follows: A, 29.3 %; C, 17.3 %; G, 21.0 %; and T, 32.4 %. The G+C content is 38.3 %. NTU156 possesses the putative transcription regulatory sequence (TRS) motif, 5′-CUAAAC-3′, at the 3′ end of the leader sequence and preceding each ORF (Table 2).

Table 2.

Coding potentials and putative transcription regulatory sequences (TRS) of FCoV NTU156

| ORFs | Start–end (nucleotide position) | No. of nucleotides | No. of amino acids | Putative TRS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide position | TRS sequences | ||||

| ORF 1a | 313–2,417 | 12,105 | 4,035 | 94 | GAACUAAACGAA210AUG |

| ORF 1ab |

313–20,417 (shift at 12,381) |

20,105 | 6,701 | ||

| S | 20,414–24,775 | 4,362 | 1,453 | 20,382 | UUACUAAACUUU23AUG |

| ORF 3a | 24,840–25,076 | 237 | 78 | 24,832 | GAACUAAACUUAUG |

| ORF 3b | 25,021–25,236 | 216 | 71 | ||

| ORF 3c | 25233–25,433 | 201 | 66 | ||

| E | 25,512–25,760 | 249 | 82 | 25,469 | GUUCUAAACGAA37AUG |

| M | 25,771–26,556 | 786 | 261 | 25,762 | GAACUAAACAAAAUG |

| N | 26,569–27,687 | 1,119 | 372 | 26,557 | UAACUAAACUUCUAAAUG |

| ORF 7a | 27,692–27,997 | 306 | 101 | 27,684 | GAACUAAACGCAUG |

| ORF 7b | 28,002–28,622 | 621 | 206 | ||

5′, 3′ Untranslated regions (UTRs) and open reading frames (ORFs)

The 5′-UTR of FCoV NTU156 comprises 312 nts—one or two nts more than other known FCoVs (79–1146: 311 nts, black: 311 nts, C1Je: 310 nts)—whereas the 3′-UTR of our virus comprises 275 nts, which is identical to other FCoVs. The 5′ two-thirds of the genome contain the 1a (nt 313–12,417) and 1ab (nt 313–20,417) genes that encode the nonstructural polyproteins. A typical coronavirus “slip site,” 5′-UUUAAAC-3′ (nt 12,381–12,387) is located within this gene. These genes are followed by genes encoding the four structural proteins: spike (nt 20,414–24,775), envelope (nt 25,512–25,760), membrane (nt 25,771–26,556), and nucleocapsid (26,569–27,687) (Table 2). The two strings of accessory genes identified in all of the known FCoVs, i.e., ORF 3ab and ORF 7ab, were found in NTU156 as well (Table 2). However, an in-frame deletion of 442 nucleotides in ORF 3c was identified, which resulted in a relatively short gene comprising only 201 nts.

Genetic comparison and phylogenetic analysis with other alphacoronaviruses

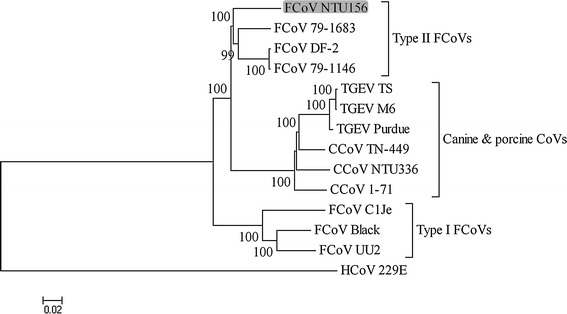

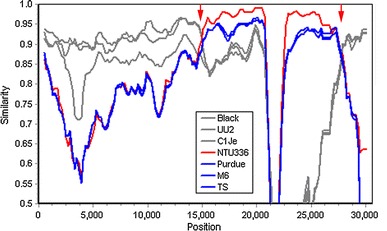

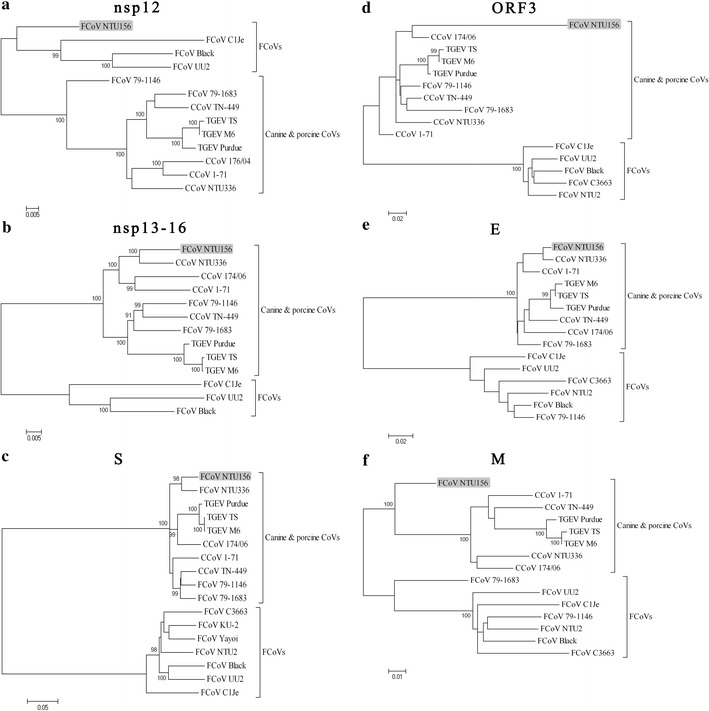

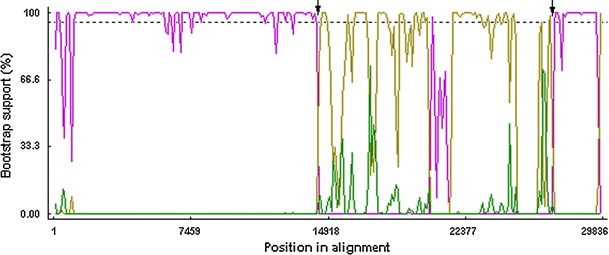

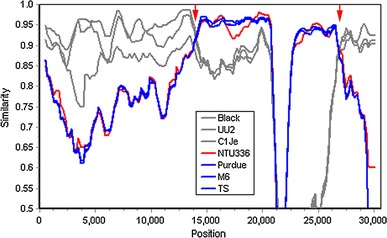

The overall sequence comparison revealed that NTU156 was more closely related to known subgroup 1a CoV but not 1b within alphacoronaviruses (Fig. 1). Nucleotide sequences similarity graphs of NTU156 with known type I FCoVs, CCoVs, and TGEVs were created by the Simplot software. The results showed that NTU156 was more closely related to type I FCoVs from the 5′ end of the genome to position 15,000 and from position 27,500 to 3′-UTR (Fig. 2). Genes located at the 5′ end (nsp1-11) and 3′ end (the N gene through ORF7) of NTU156 show consistently high similarity to type I FCoVs, whereas from nsp13 through the E sequence, the similarity to canine and porcine CoVs varies dramatically (Fig. 3). These data indicate that NTU156 might have arisen from recombination events between different strains of CoVs from species other than cats. Two possible recombination sites, at approximate positions 14,300 and 27,300, corresponding to the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and the M gene, respectively (Fig. 4), were further analyzed.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships constructed using the complete genome sequences of FCoV NTU156 and other alphacoronaviruses. Analysis was performed using MEGA 4 software and neighbor-joining methods based on 1,000 replicates. Bootstrap support values greater than 90 are shown

Fig. 2.

Nucleotide sequence similarity of the complete genome of FCoV NTU156 with other alphacoronaviruses. A similarity plot was constructed to identify the sequence homology between type I FCoVs black, C1Je, and UU2 (gray); CCoV NTU336 (red); and TGEV purdue, M6, and TS (blue). Red arrows represent putative recombination regions. A similarity of 1.0 indicates regions that share 100 % nucleotide identity. The similarity calculation was performed using the following parameters: a window size of 1,000 bp and a step size of 200 bp for the full-length sequence

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationships constructed using nsp12 (a), nsp13-16 (b), S gene (c), ORF3 gene (d), E gene (e), and M gene (f) sequences of FCoV NTU156 and other alphacoronaviruses. Analysis was performed using MEGA 4 software and neighbor-joining methods based on 1,000 replicates. Bootstrap support values greater than 90 are shown

Fig. 4.

Bootscan analysis of the complete genome of FCoV NTU156 with other alphacoronaviruses (type I FCoV UU2: pink; CCoV NTU336: yellow; TGEV purdue: green). Analysis was performed using RDP software and neighbor-joining methods based on 1,000 replicates. Putative recombination regions are indicated with arrow. The boostrap support calculation was undertaken using a window size of 1,000 bp and a step size of 200 bp. Dashed line indicates the 95 % bootstrap support threshold values

Phylogenetic trees using the nucleotide sequence of genes for putative proteins and polypeptides of alphacoronaviruses were further constructed. At nsp 1 through nsp 11 (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and from N gene (Supplementary Fig. 1b) to the ORF 7ab gene (Supplementary Fig. 1c), NTU156 was more closely related to type I FCoVs. At the nsp 12 (RdRp) and the M gene, NTU156 was not clustered with any known alphacoronavirues (Fig. 3a, f). From the nsp13 through the E gene, NTU156 was clustered with CCoV (Fig. 3b–e). Taken together, these data indicated that NTU156 might have evolved from two recombination events with CCoV, with the sites of recombination located in the RdRp and M genes.

Discussion

A unique feature of CoV genetics is the high frequency of RNA recombination both in vivo and in vitro [18]. Here, an interspecies recombination between feline and canine CoV was identified in a viral strain NTU156, which was isolated from the pleural effusion of a FIP cat. This is the first time that evidence for natural recombination has been documented through the complete genome sequence analysis of type II FCoV. In 1998, Herrewegh et al., based on partial sequence analysis, first determined that type II FCoVs 79-1146 and 79-1683 originated from a homologous RNA recombination event between type I FCoV and CCoV [17]. The complete sequence of strain 79-1146 was later published in 2005 [1]. When comparing strain 79-1146, 79-1683, DF-2, and our NTU156 strain, the only four type II FCoVs that have had their full-length genomes sequenced to date, a common phenomenon was found; both viruses arose from a double recombination event between type I FCoV and coronaviruses from other species.

NTU156 appears to have evolved from a recombination between type I feline and canine CoV; however, when we aligned the genes in which recombination took place with other type II FCoVs, genome crossovers with other alphacoronavirus were noted. When the sequences around the putative recombination sites were examined, i.e., one located in the 5′ region (strain 79-1146) and two in the 3′ region (strain 79-1146, and 79-1683), porcine coronavirus (TGEV) was also found to contribute to the evolution of type II FCoV (in addition to CCoV) (Figs. 3b, 5). This finding is not surprising because the receptor for type II FCoV, feline aminopeptidase N, has been found to serve as a receptor for several CoVs, including canine, porcine, and human CoVs [30]. Therefore, the interspecies recombination of type I FCoV with any of the above viruses might occur in nature. The recombination of type I FCoV in cats living in the same household with dogs or living close to pig farms could give rise to type II FCoV.

Fig. 5.

Nucleotide sequence similarity of the complete genome of FCoV 79-1146 with other alphacoronaviruses. A similarity plot was constructed to identify the sequence homology between type I FCoVs black, C1Je, and UU2 (gray); CCoV NTU336 (red); and TGEV purdue, M6, and TS (blue). Red arrows represent putative recombination regions. A similarity of 1.0 indicates regions that share 100 % nucleotide identity. The similarity calculation was performed using the following parameters: a window size of 1,000 bp and a step size of 200 bp for full-length sequences

Based on the analysis of the four full genomes of type II FCoV available at present (NTU156, 79-1146, 79-1683, and DF-2), type II FCoVs appear to retain type I FCoV sequences in their 5′ and 3′ ends. We asked whether the genes located in these regions are indispensable for FCoV replication in cats. To answer that question, the amino acid sequence of genes retained at both ends of FCoVs, CCoVs, and TGEVs, i.e., nsp 1 through nsp 11 and the N and ORF7 genes, were further aligned and compared (Table 3). In contrast to the greater than 90 % of amino acid homology between different strains of FCoVs, the nsp 2, 3, and 6, as well as the N gene and the ORF7a gene of FCoVs, when compared with CCoVs or TGEVs, exhibited similarity of less than 80 %. This finding indicates that these gene products might possess irreplaceable functions for FCoV replication. This might explain why type II FCoVs found in nature harbor genomes that evolved from a double recombination.

Table 3.

Percent similarity with respect to the amino acid sequences of FCoV NTU156 and other alphacoronaviruses

| Gene | FCoV | CCoV | TGEV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTU2 | Black | C1Je | NTU336 | 174/06 | Purdue | TS | |

| ORF1 | |||||||

| nsp1 | –a | 93.6 | 92.7 | 91.8 | – | 92.7 | 91.8 |

| nsp2 | – | 93.6 | 91.7 | 80.2 | – | 79.1 | 78.7 |

| nsp3 | – | 91.5 | 84.9 | 79.2 | – | 78.8 | 78.3 |

| nsp4 | – | 96.3 | 93.5 | 88.8 | – | 88.2 | 87.1 |

| nsp5 | – | 97.4 | 96.7 | 93.4 | 93.4 | 93.0 | 92.7 |

| nsp6 | – | 93.9 | 91.5 | 77.9 | 76.5 | 77.9 | 77.2 |

| nsp7 | – | 97.6 | 97.6 | 97.6 | 96.4 | 96.4 | 96.4 |

| nsp8 | – | 97.9 | 96.4 | 92.8 | 90.8 | 92.8 | 92.3 |

| nsp9 | – | 95.5 | 96.4 | 86.5 | 91.0 | 89.2 | 89.2 |

| nsp10 | – | 98.5 | 97.8 | 95.6 | 95.6 | 95.6 | 94.8 |

| nsp11 | – | 94.7 | 100 | 84.2 | 84.2 | 84.2 | 84.2 |

| N | 93.3 | 92.0 | 91.7 | 77.5 | 77.2 | 76.4 | 76.9 |

| ORF7 | |||||||

| 7a | 99.0 | 97.1 | 96.1 | 81.4 | 81.4 | 78.5 | 74.7 |

| 7b | 88.9 | 86.9 | 86.7 | 59.9 | 61.8 | – | – |

aNot available

Although the prevalence of type II FCoV is consistently lower (2–11 %) than type I virus around the world (88–98 %) [9–16], our previous study indicates that infection of type II FCoV correlates significantly with FIP when compared to type I [10]. As shown in the present study, type II FCoV arises by exchanging a large genome fragment (approximately 12 kb) of type I FCoV with other members of alphacoronaviruses. The genes exchanged through this double recombination include nsp 13–16, structure protein S (spike), and accessory protein 3abc. The nsp 13–16 proteins are replication proteins with functions such as helicase activity (nsp 13), nucleoside triphosphatase activity (nsp 13), RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity (nsp 13), 3′–5′ exoribonuclease activity (nsp 14), RNA cap formation (nsp 14 and nsp 16), and endonuclease activity (nsp 15) [31]. It has ben reported that the function of the 3c protein might be crucial for viral replication in the gut but is dispensable for systemic FCoV replication [32]. However, S proteins play a crucial role in receptor binding and eliciting protective immunity [33]. Through the replacement of nearly one-third of the genome, the new virus might gain new antigenicity, posing a threat to cats that either have been infected with a type I virus before or never have been infected with FCoV.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Fig. 1 Phylogenetic relationships constructed using nsp1-11 (a), N gene (b), and ORF7 (c) sequences of FCoV NTU156 and other alphacoronaviruses. Analysis was performed using MEGA 4 software and neighbor-joining methods based on 1,000 replicates. Bootstrap support values greater than 90 are shown (JPEG 1680 kb)

References

- 1.Dye C, Siddell SG. J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:2249–2253. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80985-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dye C, Siddell SG, Feline J. Med. Surg. 2007;9:202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tekes G, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Stallkamp I, Thiel V, Thiel HJ. J. Virol. 2008;82:1851–1859. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02339-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ, Zhang JX, Peiris JS, Chen H, Guan Y. J. Virol. 2007;81:4012–4020. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02605-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedersen NC, Boyle JF, Floyd K, Fudge A, Barker J. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1981;42:368–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedersen NC, Feline J. Med. Surg. 2009;11:225–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen NC, Black JW, Boyle JF, Evermann JF, McKeirnan AJ, Ott RL. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1984;173:365–380. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9373-7_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen NC, Ward J, Mengeling WL. Arch. Virol. 1978;58:45–53. doi: 10.1007/BF01315534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hohdatsu T, Okada S, Ishizuka Y, Yamada H, Koyama H. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1992;54:557–562. doi: 10.1292/jvms.54.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin CN, Su BL, Wang CH, Hsieh MW, Chueh TJ, Chueh LL. Vet. Microbiol. 2009;136:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Addie DD, Schaap IA, Nicolson L, Jarrett O. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84:2735–2744. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benetka V, Kubber-Heiss A, Kolodziejek J, Nowotny N, Hofmann-Parisot M, Mostl K. Vet. Microbiol. 2004;99:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duarte A, Veiga I, Tavares L. Vet. Microbiol. 2009;138:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kummrow M, Meli ML, Haessig M, Goenczi E, Poland A, Pedersen NC, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Lutz H. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2005;12:1209–1215. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.10.1209-1215.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiba N, Maeda K, Kato H, Mochizuki M, Iwata H. Vet. Microbiol. 2007;124:348–352. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vennema H. Vet. Microbiol. 1999;69:139–141. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(99)00102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrewegh AA, Smeenk I, Horzinek MC, Rottier PJ, de Groot RJ. J. Virol. 1998;72:4508–4514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4508-4514.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai MMC, Perlman S, Anderson LJ. In: Fields Virology. Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SEE, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1305–1335. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hon CC, Lam TY, Shi ZL, Drummond AJ, Yip CW, Zeng F, Lam PY, Leung FC. J. Virol. 2008;82:1819–1826. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01926-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stavrinides J, Guttman DS. J. Virol. 2004;78:76–82. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.1.76-82.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pyrc K, Dijkman R, Deng L, Jebbink MF, Ross HA, Berkhout B, van der Hoek L. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;364:964–973. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo PC, Lau SK, Yip CC, Huang Y, Tsoi HW, Chan KH, Yuen KY. J. Virol. 2006;80:7136–7145. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00509-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks JE, Rainer AC, Parr RL, Woolcock P, Hoerr F, Collisson EW. Virus Res. 2004;100:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia W, Karaca K, Parrish CR, Naqi SA. Arch. Virol. 1995;140:259–271. doi: 10.1007/BF01309861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kusters JG, Jager EJ, Lenstra JA, Koch G, Posthumus WP, Meloen RH, van der Zeijst BA. J. Immunol. 1989;143:2692–2698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Junker D, Collisson EW. Virology. 1993;192:710–716. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin CN, Su BL, Wu CW, Hsieh LE, Chueh LL. Taiwan Vet. J. 2009;35:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lole KS, Bollinger RC, Paranjape RS, Gadkari D, Kulkarni SS, Novak NG, Ingersoll R, Sheppard HW, Ray SC. J. Virol. 1999;73:152–160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.152-160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin DP, Lemey P, Lott M, Moulton V, Posada D, Lefeuvre P. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2462–2463. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tresnan DB, Levis R, Holmes KV. J. Virol. 1996;70:8669–8674. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8669-8674.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perlman S, Netland J. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:439–450. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang HW, de Groot RJ, Egberink HF, Rottier PJ. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:415–420. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.016485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du L, He Y, Zhou Y, Liu S, Zheng BJ, Jiang S. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1 Phylogenetic relationships constructed using nsp1-11 (a), N gene (b), and ORF7 (c) sequences of FCoV NTU156 and other alphacoronaviruses. Analysis was performed using MEGA 4 software and neighbor-joining methods based on 1,000 replicates. Bootstrap support values greater than 90 are shown (JPEG 1680 kb)