Abstract

Porcine astrovirus (PAstV) belongs to genetically divergent lineages within the genus Mamastrovirus. In this study, 25/129 (19.4 %) domestic pig and 1/146 (0.7 %) wild boar fecal samples tested in South Korea were positive for PAstV. Positive samples were mainly from pigs under 6 weeks old. Bayesian inference (BI) tree analysis for RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and capsid (ORF2) gene sequences, including Mamastrovirus and Avastrovirus, revealed a relatively geographically divergent lineage. The PAstVs of Hungary and America belong to lineage PAstV 4; those of Japan belong to PAstV 1; and those of Canada belong to PAstV 1, 2, 3, and 5, but not to 4. This study revealed that the PAstVs of Korea belong predominantly to lineage PAstV 4 and secondarily to PAstV 2. It was also observed that PAstV infections are widespread in South Korea regardless of the disease state in domestic pigs and in wild boars as well.

Keywords: Pig, Astrovirus, Phylogeny

Astroviruses are single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses of approximately 7 kb in length, with spherical, non-enveloped virions of about 30 nm in diameter. These viruses generally exhibit a distinctive five- or six-pointed star-shape appearance when viewed by electron microscopy (EM) [1]. As a cause of gastroenteritis in young children, astrovirus infections are currently second only to rotavirus infections in importance, but in animals their association with enteric diseases is not well documented, with the exception of turkey and mink astrovirus infections [2].

Family Astroviridae is separated into two genera. Viruses of the genus Mamastrovirus infect mammals, and those of Avastrovirus infect avian [3]. Avastroviruses include duck astrovirus 1 (DAstV-1), turkey astrovirus 1 and 2 (TAstV-1 and TAstV-2), and avian nephritis virus (ANV) [2]. Mamastroviruses appear to have a broad host range, including human [1], sheep [4], cow [5], pig [6], dog [7], cat [8], red deer [9], mouse [10], mink [11], bat [12], cheetah [13], brown rat [14], roe deer [15], sea lion and dolphin [16], and rabbit [17].

Porcine astrovirus (PAstV) was first detected by EM in the feces of a diarrheic piglet [6] and was later isolated in culture [18]. Molecular characterization of the capsid (ORF2) gene from this isolate followed some years later [19]. Since then, research groups have successfully used PCR approaches to investigate the presence and diversity of PAstV [20–22]. PAstV has been detected in several countries, including South Africa [23], the Czech Republic [20], Hungary [22], Canada [21], and Colombia [24]. In South Korea, there have been studies done on astrovirus but were only limited to its detection in human infection. There has been no attempt yet to know the extent of astrovirus infection in the pig population of the country. It was, therefore, the aim of this study to investigate the genetic groups of Korean PAstV in domestic pigs and wild boars and to identify the incidence of co-infection with other porcine enteric viruses as well.

A total of 129 fecal samples of domestic pigs (60 piglets under 3 weeks old, 45 weaned pigs, 14 growing-finishing pigs, and 10 sows over 1 year old) was collected from six piggery farms with good breeding facilities in four provinces of South Korea from January to June 2011. Out of these collected samples 90 were from diarrheic and 39 were from non-diarrheic pigs. A total of 146 fecal samples of wild boars over 1 year old was collected from the wildlife areas in five provinces of South Korea during the hunting season from December 2010 to January 2011. Out of these collected samples 34 were from diarrheic and 112 were from non-diarrheic boars.

Viral RNA was extracted from the feces using TRIzol LSb according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PAstV was detected in fecal specimens by RT-PCR, as previously described [22], with primers specific for the RdRp and ORF2 regions of PAstV (PAstV-F, 5′-TGACATTTTGTGGATTTACAGTT-3′ and PAstV-R: 5′-CACCCAGGGCTGACCA-3′). The RT-PCR process resulted in the amplification of a 799-nt-long fragment at an annealing temperature of 45 °C. Products of the expected size were cloned with the pGEM-T Vector System II™ (Promega, Cat. No. A3610, USA). The cloned gene was sequenced with T7 and SP6 sequencing primers on an ABI Prism® 3730xi DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at the Macrogen Institute (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea). The sequences of all the positive samples for PAstV were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers JQ696831–JQ696856. The astroviruses used in this study are listed in Table 1 along with their GenBank accession numbers.

Table 1.

Astrovirus isolates used in the present study

| Virus strains or name | Place and year | Species | Accession nos. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human astrovirus 1 | South Korea, 2006 | Human | JN887820 |

| Human astrovirus 2 | Human | *L06802 | |

| Human astrovirus 3 | Human | AF292074 | |

| Human astrovirus 4 | China, 2007 | Human | DQ344027 |

| Human astrovirus 5 | Brazil | Human | DQ028633 |

| Human astrovirus 6 | Human | AF292077 | |

| Human astrovirus 7 | Human | AF248738 | |

| Human astrovirus 8 | Human | AF260508 | |

| HMO astrovirus A | Nigeria, 2007 | Human | NC_013443 |

| HMO astrovirus B | Nizeria, 2007 | Human | GQ415661 |

| HMO astrovirus C | Thailand, 2001 | Human | GQ415662 |

| Astrovirus VA1 | USA, 2008 | Human | FJ973620 |

| Astrovirus MLB1 | Australia, 1999 | Human | FJ222451 |

| Feline astrovirus | Cat | *AF056197 | |

| Dog astrovirus | Italy, 2005 | Dog | FM213330 |

| Mink astrovirus | Mink | AY179509 | |

| Rabbit astrovirus | Rabbit | JN052023 | |

| Rat astrovirus | Hong Kong, 2007 | Rat | HM450382 |

| Ovine astrovirus | Sheep | NC_002469 | |

| CcAstV-1 | Denmark, 2010 | Deer | HM447045 |

| CcAstV-2 | Denmark, 2010 | Deer | HM447046 |

| Dolphin AstV1 | USA, 2007 | Dolphin | FJ890355 |

| Cali. sea lion AstV 1 | USA, 2006 | Sea Lion | FJ890351 |

| Cali sea lion AstV 2 | USA, 2008 | Sea Lion | FJ890352 |

| PAstV-2/2007/HUN | Hungary, 2007 | Pig | GU562296 |

| PoAstV12-3 | Canada, 2006 | Pig | HM756258 |

| PoAstV12-4 | Canada, 2006 | Pig | HM756259 |

| PoAstV14-4 | Canada, 2006 | Pig | HM756260 |

| PoAstV16-2 | Canada, 2006 | Pig | HM756261 |

| Porcine astrovirus | Japan | Pig | *Y15938 |

| Porcine astrovirus | Japan, 1983 | Pig | *AB037272 |

| Porcine astrovirus CC12 | Pig | JN088537 | |

| PAstV/1104/MN | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272548 |

| PAstV/1115/MS | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272559 |

| PAstV/1102/IL | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272546 |

| PAstV/1116/PA | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272560 |

| PAstV/1117/MN | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272561 |

| PAstV/1118/NC | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272562 |

| PAstV/1122/MN | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272566 |

| PAstV/1123/MN | USA, 2010 | Pig | *JF272567 |

| PAstV/1124/IL | Pig | JF272568 | |

| PAstV/1128/VA | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272572 |

| PAstV/1125/NE | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272569 |

| PAstV/1134/KS | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272578 |

| PAstV/1137/NE | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272581 |

| PAstV/1138/MEX | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272582 |

| PAstV/1139/NC | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272583 |

| PAstV/1140/OK | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272584 |

| PAstV/1142/MN | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272586 |

| PAstV/1154/IL | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272598 |

| PAstV/1155/IL | USA, 2010 | Pig | JF272599 |

| PAstK4 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696831 |

| PAstK5 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696832 |

| PAstK12 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696833 |

| PAstK21 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696834 |

| PAstK22 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696835 |

| PAstK29 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696836 |

| PAstK31 | Korea/Gy, 2011 | Wild boar | JQ696837 |

| PAstK32 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696838 |

| PAstK37 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696839 |

| PAstK54 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696840 |

| PAstK60 | Korea/Ka, 2011 | Pig | JQ696841 |

| PAstK63 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696842 |

| PAstK65 | Korea/Gy, 2011 | Pig | JQ696843 |

| PAstK73 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696844 |

| PAstK76 | Korea/Gy, 2011 | Pig | JQ696845 |

| PAstK78 | Korea/Ka, 2011 | Pig | JQ696846 |

| PAstK103 | Korea/Ka, 2011 | Pig | JQ696847 |

| PAstK110 | Korea/Ka, 2011 | Pig | JQ696848 |

| PAstK114 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696849 |

| PAstK118 | Korea/Ka, 2011 | Pig | JQ696850 |

| PAstK119 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696851 |

| PAstK120 | Korea/Ka, 2011 | Pig | JQ696852 |

| PAstK123 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696853 |

| PAstK124 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696854 |

| PAstK126 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696855 |

| PAstK127 | Korea/Ch, 2011 | Pig | JQ696856 |

| WBAstV-1 | Hungary, 2011 | Wild boar | JQ340310 |

| AFCD11 | Hong Kong, 2005 | Bat | EU847145 |

| AFCD57 | Hong Kong, 2005 | Bat | EU847144 |

| LD38 | China, 2007 | Bat | FJ571065 |

| LD77 | China, 2007 | Bat | FJ571066 |

| LD71 | China, 2007 | Bat | FJ571067 |

| LS11 | China, 2007 | Bat | FJ571068 |

| Chicken astrovirus1 | Chicken | NC_003790 |

Most of the isolates were used for both RdRp and ORF2 analysis. Few others (with asterisk (*) on the corresponding accession number) were used only for ORF2 analysis. The new sequences are marked in bold fonts

Ch Chungchung, Gy Gyunggi, Ka Kangwon

To investigate the relationship between Astroviruses and other economically important viral diseases that cause diarrhea in piglets in Asia, screening tests were conducted to detect Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus (PEDV), Transmissible Gastroenteritis Virus (TGEV), and Porcine Group A Rotavirus (GAR), as previously described [25]. The primer pairs used in this study were P1 (TTCTGAGTCA CGAACAGCCA, 1466–1485) and P2 (CATATGCAGCCTGCTCTGAA, 2097–2116) for the S gene of PEDV, T1 (GTGGTTTTGGTYRTAAATGC, 16–35) and T2 (CACTAACCAACGTGGARCTA, 855–874) for the S gene of TGEV, and rot3 (AAAGATGCTAGGGACAAAATTG, 57–78) and rot5 (TTCAGATTGT GGAGCTATTCCA, 344–365) for the segment 6 region of group A Rotavirus. The sizes of the expected products of multiplex RT-PCR were 859 bp for TGEV, 651 bp for PEDV, and 309 bp for rotavirus, which could be differentiated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Out of the 129 domestic pig fecal samples tested, 25 were positive for PAstV. Prevalence of PAstV in weaned pigs (35.6 %, 16/45) was higher than that in suckling piglets (15.0 %, 9/60) and in growing-finishing pigs (9.1 %, 1/14) (Table 2). Only one wild boar which is coming from the province of Gyunggi tested positive for PAstV (0.7 %, 1/146). The low prevalence of PAstV in wild boars might have been due to the fact that usually older animals (over 1 year old) have lesser susceptibility to infection and generally wild pigs are more resistant to many diseases than the domesticated ones.

Table 2.

Porcine astrovirus infection status of diarrheic and healthy pigs and its association with other viruses

| Animal species | Age | Province | No. of diarrheic and healthy pigs | Reverse transcript (RT)-PCR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAstV | PGAR | PEDV | TGEV | ||||

| Domestic pigs |

Suckling pigs (≤ 3 weeks; n = 60) |

Gyunggi and Chungchung | Diarrheic (n = 33) | 4/33 (12.1 %) | 10/33 (30.3 %) | 0 | 0 |

| Healthy (n = 27) | 5/27 (18.5 %) | 7/27 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Weaned pigs (≤ 6 weeks; n = 45) | Kangwon and Chungchung | Diarrheic (n = 39) | 13/39 (33.3 %) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Healthy (n = 6) | 3/6 (50 %) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

|

Growth-finishing pigs (≤ 22 weeks; n = 14) |

Gyunggi | Diarrheic (n = 11) | 1/11 (9.1 %) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Healthy (n = 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Sows (≥1 year, n = 10) | Gyungsang | Diarrheic (n = 7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Healthy (n = 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Wild boar | Wild boar (≥1 year, n = 146) | Kangwon | Diarrheic (n = 4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Healthy (n = 17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Gyunggi | Diarrheic (n = 14) | 1/48 (2.1 %) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Healthy (n = 34) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Gyungsang | Diarrheic (n = 4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Healthy (n = 21) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Jena | Diarrheic (n = 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Healthy (n = 15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Chungchung | Diarrheic (n = 9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Healthy (n = 25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | n = 275 | 27/275 (9.8 %) | 17/275 (6.2 %) | ||||

The total number of diarrheic and healthy domestic pigs with PAstV was 18/90 (20.0 %) and 8/39 (20.5 %), respectively

PAstV porcine astrovirus, PGAR porcine group A rotavirus, PEDV porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, TGEV transmissible gastroenteritis virus

The percentage of samples that were PAstV-positive differed among the six pig farms: Chungchong A, 28.6 % (10/35); Chungchong B, 22.9 % (8/35); Kangwon, 20.0 % (4/20); Gyunggi A, 7.1 % (1/14); Gyunggi B, 20.0 % (3/15), and Gyungsang, 0 % (0/10). The low or no incidence of PAstV in Gyunggi A (growing-finishing pigs) and Gyungsang (sows) can likewise be attributed to the lesser susceptibility of adult pigs to infection. The proportion of non-diarrheic and diarrheic pig fecal samples was 14.0 % (18/129) and 6.2 % (8/129), respectively. These results suggest that PAstV is widespread in South Korea regardless of the disease status (with or without clinical manifestations) of pigs. Although Astroviruses are highly prevalent in young pigs and are mostly present in diarrheic pigs, PAstV is a common finding as well in the fecal samples of apparently healthy pigs [21, 22]. The clinical significance of PAstV infection remains to be clarified.

The clinical symptoms of diarrhea are frequently reported to be associated with Rotavirus, Coronavirus, and Calicivirus-like infections in piglets [6, 18, 20, 21, 26]. Although PEDV and TGEV infections were not identified in any of the fecal samples, porcine GAR infection was identified in 6.2 % (17/275) of the samples collected from suckling pigs under 3 weeks old (Table 2). Furthermore, coinfection with PAstV and GAR was observed in two cases (one in diarrheic and one in non-diarrheic pig fecal samples). However, it is not cleared yet if GAR is directly associated with astrovirus infection in pigs.

All Astrovirus sequences were aligned initially with the ClustalX 1.8 program [27]. The nucleotide sequences were translated and the nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities among the astrovirus strains were calculated with BIOEDIT 7.053 [28]. Bayesian trees were generated with MrBayes 3.1.2 [29, 30] using best-fit models which were selected with ProtTest 1.4 [31] for amino acid alignment. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analyses were run with 1,000,000 generations for each amino acid sequence.

Bayesian posterior probabilities by MrBayes 3.1.2 were estimated on the basis of a 70 % majority rule consensus of the trees. For each analysis, a chicken astrovirus (NC_003790) was specified as the outgroup and a graphic output was produced with TreeView 1.6.1 [32]. The best modelssof the RdRp and ORF2 amino acid sequences were obtained using ProTest 1.4, which showed WAG + I + G and WAG + G + F, respectively, according to the results of the Akaike information criterion (AIC).

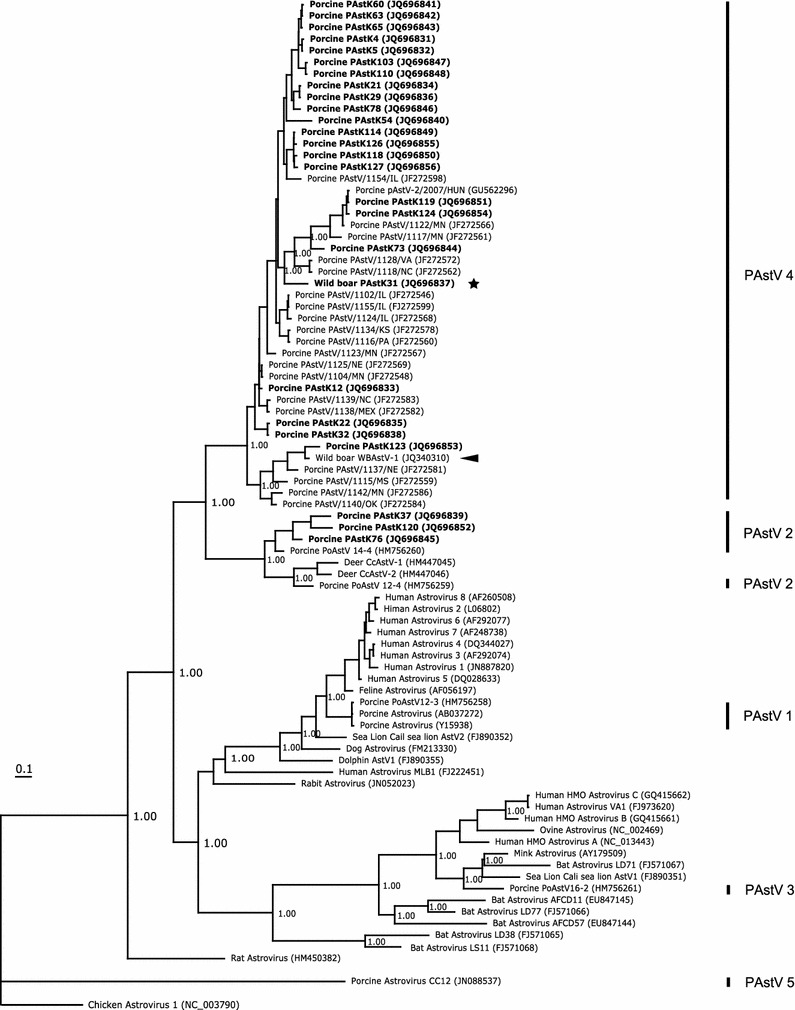

BI trees for the RdRp (Fig. 1) and ORF2 (Fig. 2) amino acid sequences revealed the presence of five unrelated PAstV lineages. The first lineage (PAstV 1) contained the PoAstV12-3 strain (HM756258) from Canadian pig and two porcine strains (Y15938 and AB037272) derived from Japanese pigs, and it adjoined the lineage of the human and feline astrovirus strains. The second lineage (PAstV 2) contained three Korean strains (JQ696839, JQ69845, and JQ69852), two Canadian strains (HM756259 and HM756260), and deer strains (HM447045 and HM447046). The third lineage (PAstV 3) contained the PoAstV16-2 strain (HM756261) from Canadian pig, and it adjoined the lineage containing human astrovirus. The fourth lineage (PAstV 4) contained only strains of domestic pigs and of a wild boar, including 1 Hungarian (GU562296), 22 Korean, and 19 American strains (Figs. 1, 2). The fifth lineage (PAstV 5) contained the PoAstV CC12 strain (JN088537) derived from Canadian pig.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationship of porcine astrovirus and prototypical astrovirus species based on the partial RdRp (ORF1b) amino acid sequence analysis. The best model of the RdRp amino acid sequence by ProTest 1.4 was WAG + I + G (deltAIC: 0.00, AIC: 7839.43, AICw: 0.53, −lnL: −3760.72). The tree was constructed using the BI method to show the phylogenetic relationship between the global Mamastrovirus strains and the Avastrovirus strain as the outgroup. Korean PAstVs are shown in bold prints, and strains isolates from Korean and Hungarian wild boar are marked with a star and an arrow, respectively. The scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship of porcine astrovirus and prototypical astrovirus species based on the partial capsid (ORF2) amino acid sequence analysis. The best model of the ORF2 amino acid sequence by ProTest 1.4 was WAG + G + F (deltAIC: 0.00, AIC: 19367.21, AICw: 0.66, −lnL: −9496.61). Korean PAstVs are shown in bold prints, and strains isolates from Korean and Hungarian wild boar are marked with a star and an arrow, respectively. The numbers above the nodes represent posterior probabilities

Interestingly, rat astrovirus (HM450382) and porcine PoAstV CC12 (JN088537) have formed two different lineages on the Bayesian trees for the RdRp and ORF2 amino acid sequences (Figs. 1, 2). Astrovirus strains contained in Group 1 (G1), 2 (G2), and 4 (G4) on the two Bayesian trees showed similar topologies. However, Astrovirus strains in Group 3 (G3) on the Bayesian tree for the ORF2 amino acid sequence were divided into G3 and Group 5 (G5) on the Bayesian tree for the RdRp amino acid sequence (Figs. 1, 2). A strain isolated from a Hungarian wild boar in 2011 [33] belonged to PAstV 4 or Group 4 (G4) that also contained PAstK31 derived from Korean wild boar.

A previous study suggested that the number of PAstV lineages extends to a total of five, all of which most likely represent distinct species of different origins [34]. However, with the available AstVs research data from countries around the world, future studies could unveil diverse genetic lineages. In this study, the porcine astrovirus strains appeared to be phylogenetically related to not only prototypical human astroviruses (as was already known) but also the recently discovered novel human strains. This finding suggests the existence of multiple cross-species transmission events between the hosts and the other animal species.

Several recent studies have shown that bats form multiple independent lineages [35, 36]. Bat astrovirus strains in this study also showed independent lineages and specifically, the LD71 (FJ571067) strain had a close relationship with astrovirus strains of human, sheep, mink, and sea lion (Figs. 1, 2).

A previous study suggested that porcine AstVs have played an active role in pigs in the evolution and ecology of the Astroviridae [21]. Recent studies have shown evidence of multiple recombination events between distinct PAstV strains and between PAstV and human astrovirus (HAstV) in the variable region of ORF2 [24], as well as interspecies recombination between porcine and deer astroviruses [37].

A study of the molecular epidemiology and genetic diversity of human astrovirus in South Korea from 2002 to 2007 revealed genotype 1 to be the most prevalent, accounting for 72.19 % of strains, followed by genotypes 8 (9.63 %), 6 (6.95 %), 4 (6.42 %), 2 (3.21 %), and 3 (1.6 %) [38]. This finding suggests that little interspecies (between human and pig) transmission has occurred until now in South Korea.

In conclusion, this study extends current knowledge of PAstV in wild boar and domestic pig. A more extensive study should be done on wild life PAstVs to further elucidate their potential role in the epidemiological landscape of the astrovirus infection in domestic pig population. To a greater length, continuous surveillance on the prevalence of both PAstVs will provide a wider understanding of the possible cross-species or human transmissions, in particular.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr. Min-Heg Lim and Ms. Sa-Ra Choi for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Madeley CR, Cosgrove BP. Lancet. 1975;2:451–452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90858-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Benedictis P, Schultz-Cherry S, Burnham A, Cattoli G. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011;11:1529–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.S.S. Monroe, Astroviridae, in Virus Taxonomy. Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, ed. by M.J. Carter, J. Herrmann, J.K. Mitchel, A. Sanchez-Fauquier (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2005), p. 859–864

- 4.Snodgrass DR, Gray EW. Arch. Virol. 1977;55:287–291. doi: 10.1007/BF01315050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woode GN, Bridger JC. J. Med. Microbiol. 1978;11:441–452. doi: 10.1099/00222615-11-4-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridger JC. Vet. Rec. 1980;107:532–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams FP., Jr Arch. Virol. 1980;66:215–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01314735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoshino Y, Zimmer JF, Moise NS, Scott FW. Arch. Virol. 1981;70:373–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01320252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tzipori S, Menzies JD, Gray EW. Vet. Rec. 1981;108:286. doi: 10.1136/vr.108.13.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kjeldsberg E, Hem A. Arch. Virol. 1985;84:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01310560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Englund L, Chriel M, Dietz HH, Hedlund KO. Vet. Microbiol. 2002;85:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(01)00472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu DK, Poon LL, Guan Y, Peiris JS. J. Virol. 2008;82:9107–9114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00857-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkins A, Wellehan JF, Jr, Childress AL, Archer LL, Fraser WA, Citino SB. Vet. Microbiol. 2009;136:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu DK, Chin AW, Smith GJ, Chan KH, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Poon LL. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:2457–2462. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.022764-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smits SL, Van LM, Kuiken T, Hammer AS, Simon JH, Osterhaus AD. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:2719–2722. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.024067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivera R, Nollens HH, Venn-Watson S, Gulland FM, Wellehan JF., Jr J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:166–173. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martella V, Moschidou P, Lorusso E, Mari V, Camero M, Bellacicco A, Losurdo M, Pinto P, Desario C, Banyai K, Elia G, Decaro N, Buonavoglia C. J. Gen. Virol. 2011;92:1880–1887. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.029025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu M, Shirai J, Narita M, Yamane T. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990;28:201–206. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.201-206.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jonassen CM, Jonassen TO, Saif YM, Snodgrass DR, Ushijima H, Shimizu M, Grinde B. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82:1061–1067. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Indik S, Valicek L, Smid B, Dvorakova H, Rodak L. Vet. Microbiol. 2006;117:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo Z, Roi S, Dastor M, Gallice E, Laurin MA, L’homme Y. Vet. Microbiol. 2011;149:316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reuter G, Pankovics P, Boros A. Arch. Virol. 2011;156:125–128. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0827-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geyer A, Steele AD, Peenze I, Lecatsas G, Afr JS. Vet. Assoc. 1994;65:164–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulloa JC, Gutierrez MF. Can. J. Microbiol. 2010;56:569–577. doi: 10.1139/W10-042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song DS, Kang BK, Oh JS, Ha GW, Yang JS, Moon HJ, Jang YS, Park BK. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2006;18:278–281. doi: 10.1177/104063870601800309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirai J, Shimizu M, Fukusho A. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi. 1985;47:1023–1026. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.47.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall TA. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Posada D, Buckley TR. Syst. Biol. 2004;53:793–808. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Page RD. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reuter G, Nemes C, Boros A, Kapusinszky B, Delwart E, Pankovics P. Arch. Virol. 2012;157:1143–1147. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1272-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao J, Li J, Hu G, Chen Z, Wu Y, Chen Y, Chen Z, Liao Y, Zhou J, Ke X, Ma L, Liu S, Zhou J, Dai Y, Chen H, Yu S, Chen Q. Arch. Virol. 2011;156:1415–1423. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu HC, Chu DK, Liu W, Dong BQ, Zhang SY, Zhang JX, Li LF, Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ, Chen HL, Poon LL, Peiris JS, Guan Y. J. Gen. Virol. 2009;90:883–887. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.007732-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurin MA, Dastor M, L’homme Y. Arch. Virol. 2011;156:2095–2099. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1088-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lan D, Ji W, Shan T, Cui L, Yang Z, Yuan C, Hua X. Arch. Virol. 2011;156:1869–1875. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1050-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeong AY, Jeong HS, Jo MY, Jung SY, Lee MS, Lee JS, Jee YM, Kim JH, Cheon DS. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011;17:402–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]