Abstract

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV) came to attention as an emerging pathogen causing severe respiratory illness in patients from the Middle East in September 2012. As of 14 June 2013, 58 human cases of MERS CoV infection have been confirmed, including 33 deaths (case fatality rate of 57%). MERS CoV is a beta-coronavirus, in the same family as SARS-CoV, and shares a probable origin from bats. No animal reservoir or intermediates have been definitely implicated in transmission. Limited human-to-human transmission has occurred within several clusters, as individuals without a recent travel history have become infected after exposure to an ill returned traveler.

Keywords: Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV), Coronavirus, Respiratory illness, SARS

Epidemiology

In September 2012, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV) came to attention as a cause of severe respiratory illness in patients from the Middle East [1, 2]. As of 14 June 2013, 58 human cases of MERS CoV infection have been confirmed resulting in 33 deaths [3]. No animal reservoir or intermediates have been definitely implicated in transmission. Limited human-to-human transmission has occurred within several clusters of cases in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the UK, France, Tunisia, and Italy [4]. The UK cluster provides the clearest evidence for human-to-human transmission. Two individuals with no history of recent travel became infected shortly after exposure to a relative infected with MERS CoV who had returned from travel [5]. However, human-to-human transmissibility of MERS CoV appears to be low, as close monitoring of health-care workers and household contacts has not revealed large numbers of secondary infections [5].

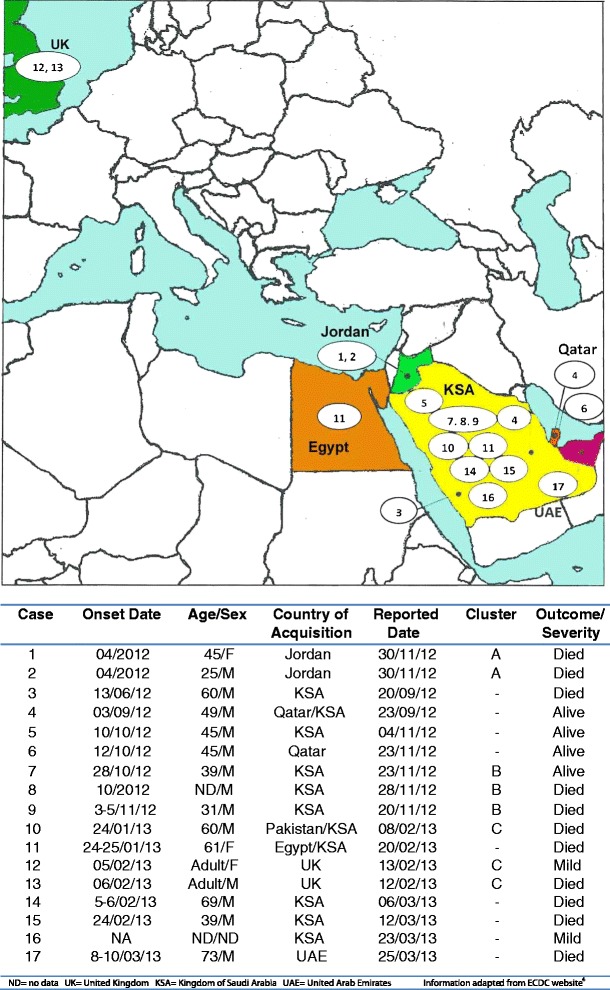

Evidence from the UK cluster suggests that the incubation period for MERS CoV is in the range 1–9 days [5], which is comparable to that for SARS. Over three-quarters of the infections have occurred in men. The three known infections in women occurred in Jordan, the UK and Egypt, which may reflect epidemiological exposure in Arabic countries. Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of confirmed cases to date, developed from data summarized by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) [4].

Fig. 1.

Locations of human Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS CoV) infections, and summary table

Virology

MERS CoV is a beta-coronavirus in the same family as the virus causing SARS. It is most closely related to coronaviruses of bat origin, and like SARS, probably originated from bats [2]. The work of Zaki et al. on respiratory samples from the first patient demonstrated that there was efficient viral replication in monkey cell lines. Apart from SARs, most other coronaviruses do not replicate well in this medium [2]. Indirect immunofluorescence assays and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for respiratory viruses including influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, and paramyxoviruses were negative, but PCR assay for the coronavirus family indicated the expected fragments [2]. Viral genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis subsequently revealed a MERS CoV in the beta-coronavirus genus, of lineage C, unlike SARS which belongs to lineage B [2].

Munster et al. at NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) successfully fulfilled Koch’s postulates in a macaque model [6]. They infected six macaque monkeys with MERS CoV causing acute pneumonia and subsequently reisolated the virus from lung tissue. MERS CoV is able to infect a broad range of mammalian cells and does not require the same receptor that restricted SARS primarily to lung tissue [7].

An interesting feature in the UK cluster was coinfection with other viruses, influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 in the index case, and type 2 parainfluenza virus in both the secondary cases [5]. This may highlight an important biological characteristic of MERS CoV or may merely reflect the presence of multiple respiratory viruses circulating ubiquitously in winter. Nevertheless, this finding has prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to adjust their screening criteria. They currently advise clinicians to test for MERS CoV even if alternate etiologies are identified, especially if clinical findings are incompletely explained by that etiology [8].

Clinical Presentation

Patients with confirmed MERS CoV have presented with a spectrum of disease ranging from mild influenza-like illness to severe pneumonia accompanied by respiratory and renal failure and resulting in death. With 11 deaths out of 17 cases, the case fatality rate (CFR) presently stands at 65 %, in contrast with the 7 % CFR of SARS [9]. The high CFR probably over-estimates illness severity because clinicians tend to pursue investigations in patients with fulminant infections who do not respond to conventional therapy. Whereas individuals with milder or self-limited infections would not necessarily undergo extensive testing that would identify novel pathogens. Serological surveys may eventually provide a better understanding of the prevalence of asymptomatic or mild MERS CoV infections.

Several of the patients were transferred to the UK or Germany for management in an intensive care unit. Despite access to excellent tertiary care, antivirals and mechanical ventilatory support, many patients succumbed to this overwhelming infection. Although information is incomplete, those with a fatal outcome were generally older than survivors (median age 60 vs. 45 years) [3].

Diagnosis

To date, all identified patients have had strong epidemiological links with travel to the Arabian peninsula, or exposure to an ill returned traveler from that region. For the first 4 months, the case definition focused on a compatible travel exposure and severe lower respiratory tract infection. The interim case definition used by WHO as of 19 February 2013 [8] includes close contact with a patient with laboratory-confirmed infection. Even with mild disease and alternate etiologies present, public health and clinical practitioners should consider the possibility of MERS CoV infection if there has been a risk of exposure.

Respiratory samples such as nose and throat swabs, sputum, endotracheal aspirates or bronchial washings should be tested for MERS CoV by RT-PCR to confirm the diagnosis. Although serum, plasma, and stool samples have been sent in some cases, the yield has been low. There are inadequate cases to confidently characterize the time-frame for seroconversion, but it is possible that like SARS, patients may not demonstrate the requisite fourfold rise in titer until 3–4 weeks after onset of acute illness.

Treatment

At this time, there is minimal evidence to guide antiviral or adjunctive therapy for this novel pathogen. As with SARS, supportive care including mechanical ventilatory support and renal replacement therapy may be the best treatment we can offer. Potentially harmful therapies such as high-dose corticosteroids should be avoided until there is a better evaluation of clinical risks and benefits.

Some studies have shown that interferon may have beneficial effects in the treatment of SARS. It may be worthwhile evaluating the efficacy of interferon therapy in the treatment of MERS CoV in properly designed randomized clinical trials if infection becomes more widespread.

Discussion

The account of how the first two cases were discovered reads like a medical detective story. It also underscores how far the international medical, scientific, and public health communities have come in the decade since SARS. The advances in sequencing technology, social media and speed of information sharing through the International Health Regulations (IHR) framework, ProMED, and other networks has given the world improved preparedness against outbreaks of novel pathogens. There is also greater awareness of the importance of infection control and personal protective equipment supplies, although lapses in care and vulnerabilities are still being discovered.

Over 2,000 pilgrims travel from Singapore to Saudi Arabia on Hajj every year. In October 2012, over 600 were scheduled to embark on this journey. With the introduction of SARS by a handful of returning travelers fresh in our collective memory, we braced ourselves and primed our system for a possible outbreak, which thankfully did not occur. Concerns that this emerging pathogen would spread via the Hajj proved unfounded; this annual mass gathering of over 2 million Muslim pilgrims did not result in a global MERS CoV pandemic. Gautret et al. screened 150 of their returning Hajj pilgrims, 40 % of whom had influenza-like illness, the so-called “Hajj cough”, but found no evidence of MERS CoV infection [10].

We do not know whether this virus will spread efficiently, or continue in sporadic clusters, as H5N1 has. Today, we stand on the brink of another zoonotic transmission event. China has reported over 100 human cases of H7N9 avian influenza infection, including 20 deaths, as of 22 April 2013 [11]. The striking difference is that the same number of H7N9 cases have occurred within the space of a month compared to 6 months with MERS CoV. Unlike SARS or MERS CoV, we have antiviral medications that could work against H7N9, and the hope of a vaccine being developed and brought to commercial quantities within 6 months. There are no proven vaccines or antiviral treatments against SARS even 10 years on, nor against the newly discovered MERS CoV. Without effective vaccines or therapeutics, classic public health interventions for outbreak control – isolation, quarantine and social distancing – may still remain the only effective countermeasures to stop new SARS and MERS CoV outbreaks, if sustained human-to-human transmissions occurs. Continued investment in research and preparedness is needed, but eternal vigilance may indeed be the price of safety from emerging infections and novel pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Vong H. Yap for his kind assistance with Adobe Photoshop enhancement of the map in Fig. 1.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflicts of Interest

Poh Lian Lim declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Tau Hong Lee declares that he/she has no conflict of interest.

Emily Rowe declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not describe any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Bermingham A, Chand MA, Brown CS, Aarons E, Tong C, Langrish C, et al. Severe respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus, in a patient transferred to the United Kingdom from the Middle East, September 2012. Eurosurveill 2012;17(40). Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20290. Accessed 22 May 2013. [PubMed]

- 2.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – update. 14 June 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_06_14/en/index.html. Accessed 16 June 2013.

- 4.ECDC. Epidemiological update: additional confirmed cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection (MERS coronanvirus) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Italy. 3 June 2013. Available from: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/press/news/Lists/News/ECDC_DispForm.aspx?List=32e43ee8%2De230%2D4424%2Da783%2D85742124029a&ID=930&RootFolder=%2Fen%2Fpress%2Fnews%2FLists%2FNews. Accessed 16 June 2013

- 5.The Health Protection Agency (HPA) UK Novel Coronavirus Investigation team. Evidence of person-to-person transmission within a family cluster of novel coronavirus infections, United Kingdom, February 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18(11). Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20427. Accessed 22 May 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Munster VJ, de Wit E, Feldmann H. Pneumonia from human coronavirus in a macaque model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1560–1562. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1215691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller MA, Raj VS, Muth D, Meyer B, Kallies S, Smits SL, et al. Human coronavirus EMC does not require the SARS-coronavirus receptor and maintains broad replicative capability in mammalian cell lines. MBio. 2012;3(6).doi:10.1128/mBio.00515-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.World Health Organization. Revised interim case definition for reporting to WHO—novel coronavirus. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/case_definition/en. Accessed 22 May 2013.

- 9.Peiris JSM, Yuen KY, Osterhaus AD, Stohr K. The severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2431–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra032498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gautret P, Charrel R, Belhouchat K, Drali T, Benkouiten S, Nougairede A, et al. Lack of nasal carriage of novel corona virus (HCoV-EMC) in French Hajj pilgrims returning from Hajj 2012, despite a high rate of respiratory symptoms. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.World Health Organization. Human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in China—update (22 April 2013). Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_04_22/en/index.html. Accessed 22 May 2013.