Abstract

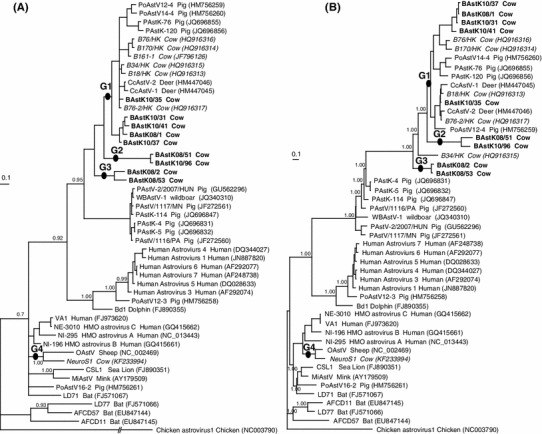

Bovine astrovirus (BAstV) belongs to a genetically divergent lineage within the genus Mamastrovirus. The present study showed that BAstV was associated with the gastroenteric tracts of cattle in nine positive fecal samples from 115 cattle, whereas no positive samples were found in the brain tissues of 14 downer cattle. Interestingly, the positive diarrheal samples were obtained mainly from calves aged 14 days–3 months. Bayesian inference tree analysis of the partial ORF1ab and capsid (ORF2) gene sequences of BAstVs identified four divergent groups. Eleven BAstVs, four porcine astroviruses, and two deer astroviruses (DAstVs; CcAstV-1 and -2) belonged to group 1; group 2 contained two BAstVs (BAstK08–51 and BAstK10–96) with another two in group 3 (BAstK08–2 and BAstK08–53); and group 4 comprised the BAstV-NeuroS1 strain derived from a cattle brain tissue sample and an ovine astrovirus. The same divergent groups were obtained when the pairwise alignments were produced using both amino acid and nucleotide sequences. The Korean BAstVs isolated from infected cattle had a nationwide distribution and they belonged to groups 1, 2, and 3.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11262-013-1013-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Astrovirus, Phylogeny, Cow

Introduction

Astroviruses are single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses that measure approximately 6.4–7.3 kb in length. The family Astroviridae comprises two genera: Mamastrovirus infects mammals and Avastrovirus infects birds [1]. Human astrovirus was first reported in children with diarrhea in 1975 [2] and mamastroviruses were found subsequently in a variety of wild hosts, including sheep, cow, pig, dog, cat, red deer, mouse, mink, bat, cheetah, brown rat, roe deer, sea lion, dolphin, and rabbit [3–16].

Bovine astrovirus (BAstV) was one of the first astroviruses [17] to be discovered and it has been isolated in the USA and the UK. Two BAstV serotypes were established based on the results of a virus neutralization assay [18]. The genomic characterization and sequence analysis of astroviruses in bovine fecal specimens collected in Hong Kong provides evidence of potential recombination in ORF2 [19]. Recently, the complete genome of a novel BAstV associated with neurological disease in cattle was sequenced, i.e., BoAstV-NeuroS1, which was phylogenetically related to an ovine astrovirus (OAstV). A previous study suggested that BoAstV-NeruoS1 infection was a potential cause of neurological disease in cattle [20]. However, genetically diverse lineages of BAstVs have not been identified in many countries because there have been few studies of astroviruses derived from cattle. Thus, the present study investigated the genetic groupings of Korean BAstVs and examined their relationships with the age of cattle infected with BAstVs.

In total, 115 fecal samples were collected from cattle with certain or suspected diarrheal disease at cattle farms throughout Korea between January 2008 and December 2010. The cattle comprised 64 calves aged <30 days and 51 cattle aged >30 days. Based on the fecal condition, 91 samples were from animals with diarrhea and 24 from nondiarrheic animals. The cattle comprised 84 Korean cattle and 31 Holstein cattle. Nonambulatory cattle which are commonly referred to as “downer” cattle are unable to stand or walk. Cattle brain tissue samples with a histopathological diagnosis of encephalitis were also collected from 14 downer cattle between 2010 and 2012. Out of 14 brain samples collected from downer cattle, 7 were found to be positive for Akabane virus and two were bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) whereas no pathogenic agent for encephalitis was detected from the other.

Viral RNA was extracted from the feces using TRIzol LSb, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. BAstV was detected in fecal specimens by RT-PCR using a specific primer set for the ORF1ab and ORF2 regions of BAstV (BAstV-F, 5′-GTGTTTGGCATGTGGGTYAARCC-3′ and BAstV-R: 5′-RTCVYYBKTGGTGGT-3′), which were designed based on known strains deposited in GenBank (accession no. HQ916313–HQ916317). The RT-PCR process amplified a 965-nt long fragment at 42 °C for 30 min, 94 °C for 5 min, 94 °C for 40 s, 51 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles using virus-specific conditions. The BAstV associated with neurological disease in cattle was also detected in brain tissue specimens by RT-PCR, as described previously [20]. Products with the expected size were cloned using the pGEM-T Vector System II™ (Promega, Cat. No. A3610, USA). The cloned gene was sequenced with T7 and SP6 sequencing primers using an ABI Prism® 3730xi DNA Sequencer at the Macrogen Institute (Macrogen Co. Ltd). The sequences of all the BAstV-positive samples were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers KF668444–KF668452.

Nine of 115 fecal samples from Korean cattle were positive for BAstV and all of the BAstVs were related to diarrhea. However, BAstV was not detected in 14 cattle brain tissue samples.

Although BAstV was first reported in England in 1987 [17], the association between bovine astroviruses and gastroenteric diseases in cattle is still not clear. A recent study reported that BAstV is not associated directly with severe diarrheic disease in calves under natural conditions [17, 19, 21, 22]. In the present study, nine Korean BAstVs were associated with clinical diarrhea in cattle where calves aged <1 month accounted for 77.8 % of cases (Table 1). A previous study shows that BAstVs were excreted by 60–100 % of calves on farms [21] while a recent study of rectal swab samples from asymptomatic adult cattle showed that only 2.4 % (5/209) contained BAstV [19]. This must be because BAstVs are more frequent in young calves than adult cattle.

Table 1.

Summary of bovine astrovirus strains isolated from South Korea

| Strain | Age | Year of isolation | Sample | Province | Co-infection with other pathogens | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAstK08/1 | 20 days | 2008 | Diarrhea | Gangwon | BRV, BKV | KF668444 |

| BAstK08/2 | 1 month | 2008 | Diarrhea | Gangwon | BKV | KF668445 |

| BAstK08/51 | 3 months | 2008 | Diarrhea | Gyonggi | – | KF668450 |

| BAstK08/53 | 3 months | 2008 | Diarrhea | Gyonggi | – | KF668451 |

| BAstK10/31 | 14 days | 2010 | Diarrhea | Chungnam | BCV, BVDV, BKV | KF668446 |

| BAstK10/35 | 1 month | 2010 | Diarrhea | Chungnam | – | KF668447 |

| BAstK10/37 | 1 month | 2010 | Diarrhea | Chungnam | BKV | KF668448 |

| BAstK10/41 | 1 month | 2010 | Diarrhea | Chungnam | BKV | KF668449 |

| BAstK10/96 | 1 month | 2010 | Diarrhea | Chungnam | BKV | KF668452 |

BRV bovine rotavirus, BCV bovine coronavirus, BVDV bovine viral diarrhea virus, BKV bovine kobuvirus, – no infection

To investigate the relationships between astroviruses and other bovine viruses that cause diarrhea in cattle, a screening test was conducted using specific primers for the detection of bovine rotavirus (BRV) [23], bovine coronavirus (BCV) [24], BVDV [25], and bovine kobuvirus (BKV) [26], as described previously.

Co-infections with other viruses were associated with the clinical symptoms of diarrhea in only two cases: the BAstK08/1 strain derived from a 20-day-old calf was co-infected with BRV and the BAstK10/31 strain from a 14-day-old calf was co-infected with both BRV and BVDV (Table 1). Although the association between BKV and diarrhea or gastroenteritis is unclear, it was co-infected with six Korean BAstVs, except for BAstK08/51, BAstK08/53, and BAstK10/35 (Table 1).

In cattle, two astrovirus serotypes have been recognized based on serological investigations, i.e., BoAstV-1 and BoAstV-2 infections [18], and recent phylogenetic analyses support the classification of BAstVs and the newly discovered astroviruses in roe deer (CcAstV) under the proposed Mamastrovirus genocluster GI [14, 19]. All of the astrovirus sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL X alignment program [27]. The nucleotide sequences were translated and the shared nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities among the astrovirus strains were calculated using BIOEDIT 7.053 [28]. The analysis of the diversity of BAstVs in the present study identified four groups based on the shared sequence identity and the phylogenetic tree of nine Korean BAstVs. There was high divergence among the amino acid sequences of the four groups based on comparisons of the partial ORF1ab and ORF2 sequences of BAstVs, i.e., relative to group 1, the shared similarity ranges were: 62.4 and 37.9–38.6 % for group 2, 71.1–73.1 and 37.9–38.6 % for group 3, and 46.2 and 26.5 % for group 4, respectively (Supplement Table).

Bayesian trees were generated with MrBayes 3.1.2 [29, 30] using best-fit models, which were selected with MrModeltest 3.7 [31] for nucleotide sequences and ProtTest 1.4 [32] for amino acid sequences. Markov Chain Monte Carlo analyses were run using 2,000,000 generations for each nucleotide and amino acid sequence. The best-fit model of the ORF1ab nucleotide sequence selected by MrModeltest 3.7 software was TrNef+G, according to the results of a hierarchical likelihood ratio test. The likelihood parameter was set to nst = 6 and rate = gamma for the datasets, and the gamma distribution shape parameter was 0.5612. The substitution model Rmat was 1.0000 (A–C), 2.8533 (A–G), 1.0000 (A–T), 1.0000 (C–G), 4.2829 (C–T), and 1.0000 (G–T). The best-fit model for the partial ORF2 amino acid sequence selected by ProTest 1.4 was JJT + I + G + F, according to Akaike’s information criterion. The relative importance levels of the parameters were: alpha (+G): 0.39, P-inv (+I): 0.00, alpha+P-inv (+I+G): 0.61, and freqs (+F): 1.00.

In the neighbor-joining tree of ORF2 genes, five BAstVs isolated in Hong Kong were closely related to CcAstV-1 and -2 [19]. Recently, the BoAstV-NeuroS1 strain was detected in the brain tissues of cattle and the analysis of its genetic diversity showed that it was most closely related to the OAstV prototype, which was identified in 1977 [3], whereas it was phylogenetically distant from a recently reported OAstV [33] and the Hong Kong BAstVs [20]. This suggests the occurrence of multiple cross-species transmission events among hosts and other animal species. However, it appears that the histopathogenic findings of encephalitis in Korean downer cows were not associated with the detection of BoAstV-NeuroS1 in brain tissue.

The BI analysis of the partial ORF1ab and/or ORF2 genes also showed that all of the known BAstVs could be separated into four groups (Fig 1a, b), in the same way as the diversity analysis. Group 1 of the BI tree contained six Hong Kong BAstVs and five Korean BAstVs, groups 2 and 3 included only Korean BAstVs, and the BoAstV-NeuroS1 strain was the only member of group 4.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships among the partial ORF1ab genes (a) and the partial ORF2 genes (b) of bovine astrovirus (BAstV) and prototypical astrovirus species. a Partial ORF1ab nucleotide sequences (-lnL: 7086.8311). The tree was constructed using TrNef+G as the best-fit model according to MrModeltest 3.7 with the Bayesian inference method, and the outgroup was chicken avastrovirus 1 (Accession No. NC_003790). b Partial capsid (ORF2) amino acid sequences (-lnL: −7251.32). The best-fit model of the ORF2 amino acid sequence was JJT+I+G+F according to ProTest 1.4. Korean BAstVs are shown in bold whereas those from other countries are shown in italic. The numbers above the nodes represent the posterior probabilities

In conclusion, the present study identified four BAstVs groups based on the phylogenetic analysis and their shared pairwise amino acid sequence identities. The BAstV detection rate in cattle feces was higher in calves aged <1 month compared with adult cattle. Thus, continuous surveillance of novel diversity in BAstVs should be conducted on many cattle farms throughout the world because of the risk of emerging astroviruses associated with neurological disease in cattle.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Soo-Kyung Joo for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Monroe SS. Astroviridae. In: Carter MJ, Herrmann J, Mitchel JK, Sanchez-Fauquier A, editors. Virus taxonomy. Eighth report of the international committee on taxonomy of viruses. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 859–864. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madeley CR, Cosgrove BP. Lancet. 1975;2:451–452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90858-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snodgrass DR, Gray EW. Arch. Virol. 1977;55:287–291. doi: 10.1007/BF01315050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woode GN, Bridger JC. J. Med. Microbiol. 1978;11:441–452. doi: 10.1099/00222615-11-4-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bridger JC. Vet. Rec. 1980;107:532–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams FP., Jr Arch. Virol. 1980;66:215–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01314735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshino Y, Zimmer JF, Moise NS, Scott FW. Arch. Virol. 1981;70:373–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01320252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzipori S, Menzies JD, Gray EW. Vet. Rec. 1981;108:286. doi: 10.1136/vr.108.13.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kjeldsberg E, Hem A. Arch. Virol. 1985;84:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01310560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Englund L, Chriel M, Dietz HH, Hedlund KO. Vet. Microbiol. 2002;85:1–11. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(01)00472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu DK, Poon LL, Guan Y, Peiris JS. J. Virol. 2008;82:9107–9114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00857-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkins A, Wellehan JF, Jr, Childress AL, Archer LL, Fraser WA, Citino SB. Vet. Microbiol. 2009;136:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu DK, Chin AW, Smith GJ, Chan KH, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Poon LL. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:2457–2462. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.022764-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smits SL, Van LM, Kuiken T, Hammer AS, Simon JH, Osterhaus AD. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:2719–2722. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.024067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivera R, Nollens HH, Venn-Watson S, Gulland FM, Wellehan JF., Jr J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:166–173. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martella V, Moschidou P, Lorusso E, Mari V, Camero M, Bellacicco A, Losurdo M, Pinto P, Desario C, Banyai K, Elia G, Decaro N, Buonavoglia C. J. Gen. Virol. 2011;92:1880–1887. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.029025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woode GN, Bridger JC. J. Med. Microbiol. 1978;11:441–452. doi: 10.1099/00222615-11-4-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woode GN, Gourley NE, Pohlenz JF, Liebler EM, Mathews SL, Hutchinson MP. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1985;22:668–670. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.4.668-670.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tse H, Chan WM, Tsoi HW, Fan RY, Lau CC, Lau SK, Woo PC, Yuen KY. J. Gen. Virol. 2011;92:1888–1898. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.030817-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L, Diab S, McGraw S, Barr B, Traslavina R, Higgins R, Talbot T, Blanchard P, Rimoldi G, Fahsbender E, Page B, Phan TG, Wang C, Deng X, Pesavento P, Delwart E. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1385–1392. doi: 10.3201/eid1909.130682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bridger JC, Hall GA, Brown JF. Infect. Immun. 1984;43:133–138. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.133-138.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woode GN, Pohlenz JF, Gourley NE, Fagerland JA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1984;19:623–630. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.5.623-630.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elschner M, Prudlo J, Hotzel H, Otto P, Sachse K. J. Vet. Med. B. 2002;49:77–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2002.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cho KO, Hasoksuz M, Nielsen PR, Chang KO, Lathrop S, Saif LJ. Arch. Virol. 2001;146:2401–2419. doi: 10.1007/s007050170011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vilcek S, Herring AJ, Herring JA, Nettleton PF, Lowings JP, Paton DJ. Arch. Virol. 1994;136:309–323. doi: 10.1007/BF01321060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita T, Ito M, Kabashima Y, Tsuzuki H, Fujiura A, Sakae K. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84:3069–3077. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall TA. Nucleic. Acids. Symp. Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Posada D, Crandall KA. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Posada D, Buckley TR. Syst. Biol. 2004;53:793–808. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reuter G, Pankovics P, Delwart E, Boros Á. Arch. Virol. 2012;157:323–327. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1151-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.