Abstract

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are often operationalized as a cumulative score, treating all forms of adversity as equivalent despite fundamental differences in the type of exposure.

Objective

To explore the suitability of this approach, we examined the independent, cumulative, and multiplicative effects of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and/or family violence on the occurrence of mental disorders in adults.

Methods

Data from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey—Mental Health were used to derive a series of logistic regression models. A set of interaction terms was included to model the multiplicative effects of ACEs on mental disorders and suicidality.

Results

The independent effects of physical abuse and sexual abuse were stronger than the effects of family violence. The cumulative effects represent nearly a 2-fold increase in disorder for each additional form of adversity. The multiplicative effects suggested that the clustering of physical abuse and sexual abuse had the greatest effect on mental disorders and suicidality.

Discussion

These findings highlight the need to examine the nuanced effects of clustering of adversity in an individual, rather than relying on a single cumulative score.

Conclusion

Future work should examine a comprehensive set of ACEs to identify which ACE combinations contribute to greater mental health burden, thereby informing the development of specific interventions.

Keywords: ACEs, ACE Study, adverse childhood experiences, anxiety, depression, substance abuse, suicidality

INTRODUCTION

The long-term effects of childhood adversity are well documented in the literature, with established links to unhealthy behaviors, physical illness, and mental disorders throughout the life course.1–4 It is estimated that more than 50% of adults experienced at least 1 adverse childhood experience (ACE) in childhood, ranging from household dysfunction to severe maltreatment.4–6

To account for the clustering of adversity in an individual, the literature has operationalized exposure in several ways. Cumulative effects are often assessed as a simple ACE count or as a categorical variable with a threshold effect (eg, ≥ 4 ACEs),4,7,8 on the basis of the original work by Felitti and colleagues.1 Although simple in application, the cumulative and threshold approaches have been criticized as treating all ACEs as equivalent, irrespective of fundamental differences in adversity.9 Thus, it is also common for researchers to examine the independent effects of each ACE by adjusting for other measured forms of adversity.2,7 Latent class analysis or factor analysis are other approaches used to model the underlying pattern of adversity rather than relying on a cumulative index.9,10

A recent study examined the individual and collective contribution of various ACEs on mental health, reporting that cumulative exposure leads to a graded increase in mental health issues above the risk of each ACE alone.2 Although this confirms that clustering of adversity increases the risk of mental health issues, it does not address whether certain combinations of adversity contribute more to the adult mental health burden than others. To continue to elucidate how various ACEs interact to affect adult mental health, we examined the independent, cumulative, and multiplicative effects of exposure to physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence on past-year major depressive episodes (depression); generalized anxiety disorder (anxiety); suicidal thoughts, plans, or attempts (suicidality); drug abuse or dependence (problematic drug use); and alcohol abuse or dependence (problematic alcohol use) among a representative sample of Canadian adults.

METHODS

This project used data from a series of annual Canadian Community Health Survey microdata files, available to accredited researchers and federal government employees through Statistics Canada (www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/help/microdata). Data were collected from the 2012 Canadian Community Health Survey—Mental Health, a cross-sectional survey that collected information on mental disorders and mental health outcomes in the past 12 months.11 In brief summary, the target population covered household residents living in Canada, excluding individuals living on reserves, residents of health institutions, full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces, and those who live in certain remote areas (< 3% of the population). The sampling frame followed a multistage procedure that formed geographic clusters, selected a household in each cluster, and sampled a single respondent from each household. The response rates at the household and individual level were 79.8% and 86.3%, with a combined response rate of 68.9% overall.11 All participants gave consent to participate in the survey after being informed about the sensitivity of the questions and their voluntary ability to refuse to participate.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Individuals who were age 18 years or older were asked a series of questions pertaining to childhood experiences before age 16 years. The childhood adversity questionnaire collected information on exposure to physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence before age 16 years. Physical abuse was defined as the experience of an adult pushing, grabbing, shoving, or throwing something at them to hurt them, or kicking, biting, punching, choking, burning, or physically attacking them in some way. Sexual abuse was classified as an adult ever forcing or attempting to force them into unwanted sexual activity by threatening, holding down, or hurting them in some way, or touching them against their will in any sexual way. Family violence was identified as witnessing parents, stepparents, or guardians hit each other or another adult in the home.

Mental Disorders and Suicidality

Past-year depression and anxiety disorders were classified using the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview, a semistructured diagnostic interview based on criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).12 Past-year suicidality was an indicator of at least 1 of the following: Serious thoughts about suicide, making a plan, or attempting suicide. Past-year problematic alcohol use and problematic drug use (cannabis or other illicit drugs) were measured with the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview, based on DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse and dependence.12

Covariates included age, sex (men, women), race (white, other), marital status (single, married/common-law, widowed/separated/divorced), and education (less than high school, high school graduate, some postsecondary education, postsecondary graduate), based on previous literature.3

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression models were used to assess the independent, cumulative, and multiplicative effects of adversity on past-year mental disorders and suicidality. The multiplicative effects were modeled using a set of interaction terms between physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence. For each model, a single 3-way interaction term and three 2-way interaction terms were included. The 3-way interaction term was tested first to determine whether the combined experience of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence was greater than expected on the basis of independent and 2-way interaction effects. Next, the 3-way interaction terms were removed from each model, and a set of models tested each 2-way interaction term. All models were hierarchically well formulated with adjustment for age, sex, race, marital status, and education. Subsequently, the analysis was stratified by sex to assess whether the effects of childhood adversity on mental health outcomes differed for male and female participants. Sample weights and bootstrap replicate weights were applied to account for oversampling and clustering methods used by Statistics Canada during sampling. All analyses were completed at the Toronto Regional Data Centre in Toronto, Canada, using Stata 15 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).13

RESULTS

The final sample was composed of 23,527 Canadian adults after excluding 319 individuals who did not provide information on childhood adversity (< 1.5%). Nearly one-third (32.5%) of participants reported an experience of childhood adversity before age 16 years. The most common adversity reported was physical abuse (22%), followed by family violence (15%) and sexual abuse (10%). Table 1 reports the descriptive characteristics of the sample stratified by their experience of early life adversity. For the entire sample, the average age was 47 years, with nearly 50% of the sample identifying as male, 78% as white, 15% as having less than high school education, 68% as graduating from a postsecondary institution, and 62% as married or common-law spouses. Individuals who experienced at least 1 ACE had a higher prevalence of past-year mental disorders, including depression (8.8% vs 2.8%), anxiety (4.8% vs 1.6%), suicidality (6.5% vs 1.8%), problematic alcohol use (4.5% vs 2.5%), and problematic drug use (2.9% vs 1.1%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic variables and mental disorders, stratified by adverse childhood experience (ACE) before 16 years old (N = 23,527)a

| Characteristic | No ACEs (n = 15,849) | At least 1 ACE (n = 7678) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (standard error) | 47.2 (0.14) | 46.8 (0.14) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 48.8 (48.1, 49.5) | 49.8 (48.3, 51.4) |

| Women | 51.2 (50.5, 51.9) | 50.2 (48.6, 51.7) |

| Racial-ethnic origin | ||

| White | 78.5 (77.0, 79.9) | 77.2 (75.5, 79.0) |

| Other | 21.5 (20.1, 23.0) | 22.8 (21.0, 24.5) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 14.6 (13.7, 15.4) | 14.6 (13.3, 15.9) |

| High school graduate | 16.8 (15.8, 17.8) | 15.6 (14.4, 16.9) |

| Some postsecondary | 6.1 (5.5, 6.8) | 8.3 (7.2, 9.5) |

| Postsecondary graduate | 62.4 (61.1, 63.8) | 61.5 (59.7, 63.4) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/common law | 63.1 (61.9, 64.3) | 63.3 (61.6, 65.0) |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 13.0 (12.2, 13.9) | 14.6 (13.4, 15.9) |

| Single | 23.9 (22.8, 24.9) | 22.1 (20.6, 23.5) |

| Mental disorders (past 12 mo) | ||

| Depression | 2.8 (2.4, 3.2) | 8.8 (7.7, 9.8) |

| Anxiety | 1.6 (1.3, 1.9) | 4.8 (4.2, 5.5) |

| Suicidality | 1.8 (1.5, 2.1) | 6.5 (5.6, 7.5) |

| Problematic alcohol use | 2.5 (2.0, 2.9) | 4.5 (3.8, 5.2) |

| Problematic drug use | 1.1 (0.8, 1.3) | 2.9 (2.3, 3.4) |

Data are percentage (95% confidence interval) unless indicated otherwise. Estimates are weighted to account for oversampling methods conducted by Statistics Canada.

Table 2 reports adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for the independent and cumulative effects of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence on adult mental disorders and suicidality. The independent effects of physical abuse and sexual abuse were stronger than family violence, with the strongest association observed between sexual abuse and suicidality (OR = 3.14; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.35–4.19). For the cumulative effect of ACEs, the ORs ranged from 1.61 (95% CI = 1.41–1.83) for problematic alcohol use to 2.15 (95% CI = 1.95–2.37) for suicidality. Collectively, this suggests the odds of each mental disorder increased by nearly 2-fold with each additional ACE.

Table 2.

Odds ratios for independent and cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences on past-year prevalence of depression, anxiety, suicidality, problematic alcohol use, and problematic drug use (N = 23,527)a

| Adverse childhood experience (ACE) | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Anxiety | Suicidality | Problematic alcohol use | Problematic drug use | |

| Physical abuse | 2.47 (1.96–3.12) | 2.26 (1.68–3.04) | 2.07 (1.50–2.85) | 1.83 (1.38–2.42) | 2.64 (1.84–3.79) |

| Sexual abuse | 2.56 (2.00–3.27) | 2.06 (1.54–2.74) | 3.14 (2.35–4.19) | 1.77 (1.17–2.68) | 2.35 (1.54–3.58) |

| Family violence | 1.22 (0.93–1.60) | 1.43 (1.03–1.99) | 1.67 (1.15–2.43) | 1.30 (0.93–1.81) | 1.43 (0.98–2.09) |

| Cumulative ACE score | 1.96 (1.79–2.14) | 1.88 (1.70–2.07) | 2.15 (1.95–2.37) | 1.61 (1.41–1.83) | 2.06 (1.79–2.37) |

Models are adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, and education.

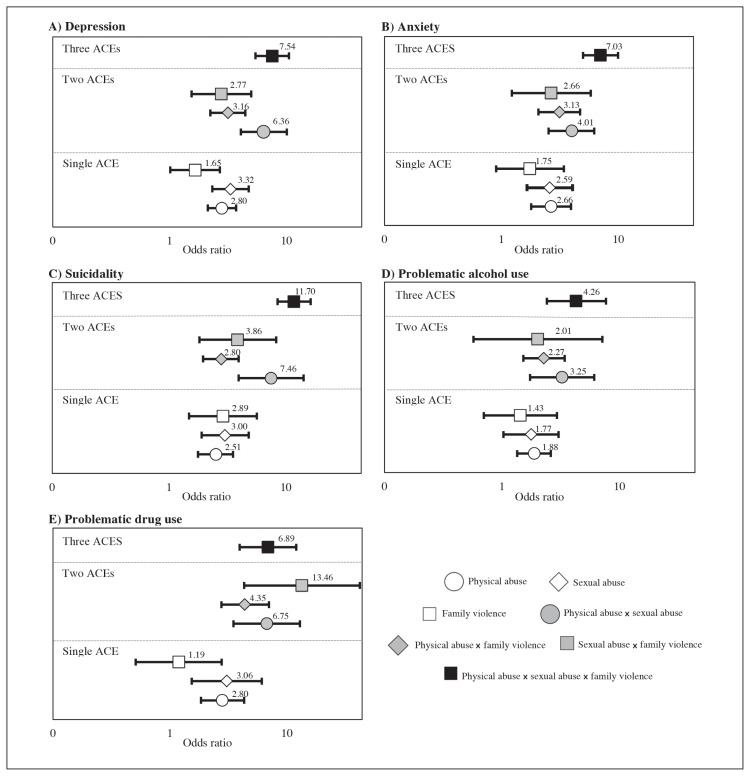

Figures 1 and 2 depict the multiplicative effects of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence on mental disorders and suicidality. Collectively, the observed comparisons suggest the ORs for combined exposure to all 3 forms of childhood adversity were similar compared with experiences of 2 forms of adversity, specifically physical abuse and sexual abuse (Figure 1). Although the ORs for depression, anxiety, suicidality, and problematic alcohol use were greatest for the combined experiences of all 3 forms of childhood adversity, the 95% CIs are wide and overlap with many estimates for combinations of 2 ACEs. For example, the ORs for depression were highest for all 3 forms of adversity (OR = 7.54; 95% CI = 5.42–10.49), yet this finding was comparable to the experience of physical abuse and sexual abuse alone (OR = 6.36; 95% CI = 4.06–10.07). Similarly, the odds of problematic substance use were greatest for sexual abuse and family violence (OR = 13.46; 95% CI = 4.31–42.10), yet the 95% CIs overlapped with the combined effect of all 3 ACEs (OR = 6.89; 95% CI = 3.94–12.06).

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratios for 3-way interaction effects of childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence on past-year A) depression, B) anxiety, C) suicidality, D) problematic alcohol use, and E) problematic drug use among adults.a

a Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, and education.

× = multiplied by; ACE = adverse childhood experience.

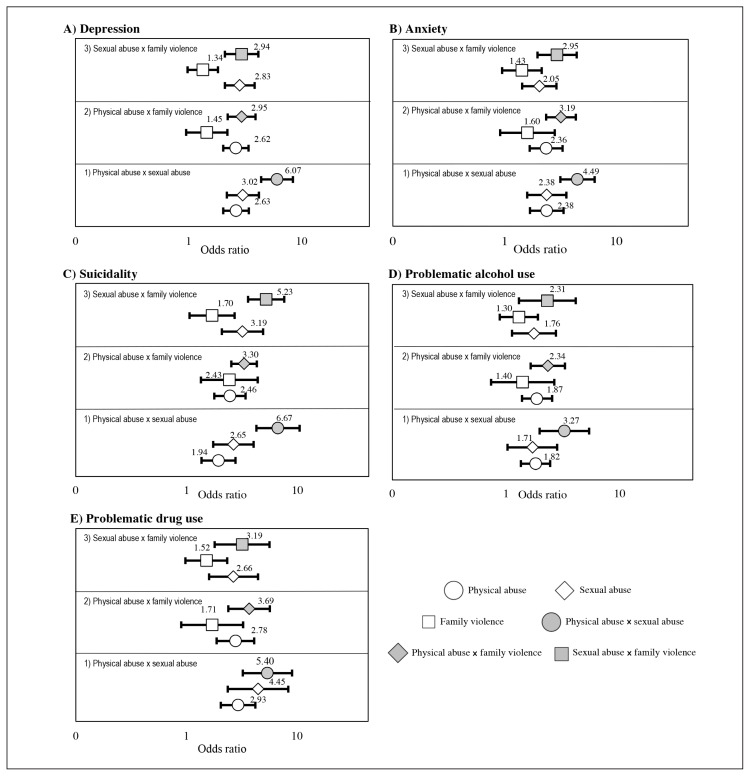

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios for 2-way interaction effects of childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence on past-year A) depression, B) anxiety, C) suicidality, D) problematic alcohol use, and E) problematic drug use among adults.a

a Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, and education.

× = multiplied by; ACE = adverse childhood experience.

Figure 2 illustrates the OR comparisons for the combined effects of 2 forms of adversity. For each mental health outcome, 3 sets of models depict the combined effects of 1) physical abuse and sexual abuse, 2) physical abuse and family violence, and 3) sexual abuse and family violence. The comparisons suggest that combined exposure to physical abuse and sexual abuse had the greatest effect on past-year mental disorders and suicidality, yet the 95% CIs for the combined effects often overlapped with the independent effects. One exception was observed for suicidality, for which the combined effects of physical abuse and sexual abuse were significantly greater than their independent effects at α = 0.05.

The sex-specific OR comparisons for the combined effects of experiencing 2 or 3 forms of adversity are reported in the Supplemental Figures 1 to 4 (available at www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.079supp.pdf). Similar to the total sample, the sex-specific comparisons suggest that the ORs for combined exposure to 3 forms of adversity were similar compared with exposure to 2 forms of adversity. Most notably, the 95% CIs for combined exposure to physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence overlapped with combined exposure to sexual abuse and family violence among men (Supplemental Figure 1, available at www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.079supp.pdf) and physical abuse and sexual abuse among women (Supplemental Figure 2, available at www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.079supp.pdf). Collectively, the sex-specific comparisons modeling the 2-way interactions suggest that the effect of sexual abuse and family violence may be greater for men compared with women (Supplemental Figures 3 and 4, available at www.thepermanentejournal.org/files/2020/19.079supp.pdf). The most notable differences were observed for suicidality, for which the ORs for combined exposure to sexual abuse and family violence for men or physical abuse and sexual abuse for women were greater than the independent effects. Although imprecision makes it challenging to draw adequate inferences, these findings suggest there may be nuanced differences between men and women with respect to combined exposure to childhood adversity on mental disorders and suicidality.

DISCUSSION

Our study examined the clustering effects of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence on mental illness and suicidality using secondary data from a nationally representative sample of Canadian adults. The combined effects of 3 forms of adversity were stronger than 2 forms of adversity for depression, anxiety, suicidality, and problematic alcohol use. For 2 forms of adversity, the combined effects of physical abuse and sexual abuse were greater than other combinations that include family violence. One exception was problematic substance use, for which sexual abuse and family violence had the strongest combined effect. These findings highlight nuanced effects that can be observed only when adversity is not collapsed into a single cumulative score, although overlapping 95% CIs suggest the odds of disorder may be similar for such combinations of adversity.

Furthermore, the sex-specific OR comparisons uncover some differences in the clustering of adversity among men and women. Specifically, these findings suggest that the combined exposure to sexual abuse and family violence may have a greater effect on mental disorders and suicidality among men compared with women, most notably for suicidality. However, some forms of adversity were uncommon, which led to imprecision of the sex-specific estimates and reduced confidence in these findings. Future work should examine the sex-specific multiplicative effects of adversity on mental disorders and suicidality using larger samples of adults.

Our results are generally consistent with studies that compared the cumulative risk score approach with factor analysis and latent class analysis approaches that model the underlying relationships between forms of adversity.9,10,13 For instance, the cumulative risk score and factor analysis approaches had similar predictive ability for symptoms of depression, drug use, and heavy drinking in early adulthood after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics; however, factor analysis was better able to examine the clustering effect of adversity on children’s mental health outcomes.9 In the studies that compared the cumulative approach with latent class analysis, the class of “high ACEs”—effectively a threshold cumulative score—revealed the strongest association with poor health outcomes over specific combinations of adversity.10,13 Specifically, Merians and colleagues13 reported that the cumulative risk score (threshold effect of ≥ 5 ACEs) behaved similarly to the latent class “high ACEs” group compared with “low ACEs,” whereas Lanier and colleagues10 provided evidence that other clusters of household dysfunction were also associated with poor health outcomes among children (eg, parental mental illness and poverty). By highlighting the clustering of physical abuse and sexual abuse, our findings corroborate the importance of examining the nuanced clustering effects of adversity on mental health in adults.

The current study adds to this growing literature as one of the first studies to examine the multiplicative effects of childhood adversity on the risk of adult mental disorders. The use of a large, nationally representative sample of Canadian adults and semistructured diagnostic interviews to assess mental disorders and suicidality further strengthens the validity of the findings.

This study also has limitations that future research can improve on. First, our analysis was limited to 3 forms of adversity. Taken in context of previous research, the combined results of these studies present an incomplete picture. Although previous research examined either abuse and neglect in the absence of household dysfunction or household dysfunction in the absence of abuse or neglect, our study examined measures of abuse and household dysfunction in the absence of neglect. Without accounting for all forms of adversity in the same analysis, the effects of the measured ACEs may be exaggerated, while other effects in unmeasured adversity are simultaneously missed. Therefore, to better assess the often nuanced impact of multiple ACEs on mental disorders, future analyses should include measures of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction or an expanded ACE inventory with items such as severe material disadvantage or exposure to adversity outside the home.14

Second, whereas childhood adversity likely precedes adult mental disorders, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to make causal inferences. Although we focused on past-year experiences of mental disorders and suicidality to mitigate the risk of reverse causation, the use of prospectively collected longitudinal data would further reduce the risk of recall bias in reporting exposure to adversity.

Third, the initial sample size of our study was large; however, the assessment of combined exposure to multiple forms of adversity limited the precision. As such, our final conclusions are based on the collective results, rather than individual findings from a single model. Although issues of stigma, prejudice, and oppression are important considerations in the field of mental health and childhood adversity, the current analysis was limited in the ability to examine racial differences in the clustering effects of adversity. Future work would benefit from the use of even larger samples or by focusing on populations with a higher prevalence of childhood adversity.

CONCLUSION

In concert with previous literature, our results suggest the cumulative approach may be appropriate to examine the clustering effect of adversity on mental disorders and suicidality; however, the nuanced effect of certain combinations, primarily physical abuse and sexual abuse, should be further examined. Future studies with a comprehensive set of ACEs are required to strengthen our confidence in the use of a cumulative approach to effectively and meaningfully measure risk associated with childhood adversity. Larger studies are needed to examine sex-based and racial differences in the multiplicative effects of ACEs on mental health outcomes in adults.

Acknowledgments

The analysis was conducted at the Toronto Regional Data Centre in Toronto, Canada, which is part of the Canadian Research Data Centre Network (CRDCN). The services and activities provided by the CRDCN are made possible by the financial or in-kind support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, Statistics Canada, and participating universities, whose support is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the CRDCN’s or those of its partners.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications performed a primary copy edit.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ Contributions

Kathryn Wiens, MSc, participated in the conduct of analysis, critical review of the results, drafting the manuscript, and submission of the final manuscript. Jennifer Gillis, MSc, and Ioana Nicolau, MSc, participated in the interpretation of analysis, critical review, and revisions of the manuscript. Terrance Wade, PhD, participated in developing the project idea and analysis plan and in critical review of the manuscript. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):245–58. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merrick MT, Ports KA, Ford DC, Afifi TO, Gershoff ET, Grogan-Kaylor A. Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abuse Negl. 2017 Jul;69:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Marti CN, Choi BY. Association of adverse childhood experiences with lifetime mental and substance use disorders among men and women aged 50+ years. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017 Mar;29(3):359–72. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017 Aug;2(8):e356–66. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert LK, Breiding MJ, Merrick MT, et al. Childhood adversity and adult chronic disease: An update from ten states and the District of Columbia, 2010. Am J Prev Med. 2015 Mar;48(3):345–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, Guinn AS. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Nov 1;172(11):1038–44. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B. Separate and cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences in predicting adult health and health care utilization. Child Abuse Negl. 2010 Jun;34(6):454–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karatekin C. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), stress and mental health in college students. Stress Health. 2018 Feb;34(1):36–45. doi: 10.1002/smi.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brumley LD, Brumley BP, Jaffee SR. Comparing cumulative index and factor analytic approaches to measuring maltreatment in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Child Abuse Negl. 2019 Jan;87:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lanier P, Maguire-Jack K, Lombardi B, Frey J, Rose RA. Adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes: Comparing cumulative risk and latent class approaches. Matern Child Health J. 2018 Mar;22(3):288–97. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Community Health Survey - Mental Health (CCHS) [Internet] Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2013. [cited 2018 Mar 14]. Available from: www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merians AN, Baker MR, Frazier P, Lust K. Outcomes related to adverse childhood experiences in college students: Comparing latent class analysis and cumulative risk. Child Abuse Negl. 2019 Jan;87:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner H, Hamby S. A revised inventory of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Child Abuse Negl. 2015 Oct;48:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]