Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the efficacy of the Female Athlete Body project (FAB) in reducing eating disorder (ED) symptoms and risk factors.

Method:

This study was a community participatory three-site, two-arm, cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT). Female collegiate athletes (N = 481) were randomly assigned by team to the FAB intervention, a behavioral ED risk factor reduction program, or a waitlist control condition. Primary analyses examined 18-month effects for ED pathology. Secondary analyses examined risk factors and correlates (e.g., thin-ideal internalization, negative mood, Female Athlete Triad knowledge, and body mass index [BMI]).

Results:

Linear mixed effects models with team as a cluster level variable and study condition as a between-subjects variable revealed significantly reduced dietary restraint in FAB teams relative to control teams. FAB teams also reported significantly fewer objective and subjective binge episodes than control teams. Finally, FAB teams showed significantly lower thin-ideal internalization and increased BMI at 18-months. No other significant differences were found.

Discussion:

This RCT examined the effects of a short intervention on ED pathology and risk factors in female collegiate athletes through 18-month follow-up. This trial is one of only three trials with female athletes that have shown long-term reductions in any ED symptoms or produced positive effects on ED risk factors. The present study is the first to find such effects with athletes using a brief (i.e., 4 hr) intervention at 18-month follow-up. Although small effects were found, the current trial provides valuable lessons about future design and implementation of similar trials with athletes.

Trial Registration:

Clinical trials NCT01735994.

Keywords: athlete, eating disorder, female athlete triad, intervention, prevention

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Eating disorders (EDs) and their associated levels of impairment, morbidity, and cost are a significant public health concern (Brownell & Walsh, 2017; Carta, Preti, & Moro, 2014; Crow, 2014; Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007). Although EDs affect people of all demographics, research indicates that some populations are at increased risk for developing EDs (Brownell & Walsh, 2017). Female athletes (FAs) represent one such population (Joy, Kussman, & Nattiv, 2017). A variety of factors contributes to FA’s increased risk (e.g., personality traits, widespread pressure that encourages attainment of a lean physique (Thompson & Sherman, 2010). It is important to note that FAs who participate in traditionally “lean” sports associated with weight or appearance requirements and expectations (e.g., gymnastics, cross country/track, and figure skating) may be at especially heightened risk (Kong & Harris, 2015; Thompson & Sherman, 2010).

Pressure to conform to a specific athletic body type can trigger ED risk factors (e.g., insufficient caloric intake), which can evolve into clinical ED symptoms. Importantly, research suggests that athletes are vulnerable to inadequate caloric intake given their athletic lifestyles (Hinton, 2005), making this a key target for intervention. Insufficient caloric intake also increases risk for the Female Athlete Triad (Mountjoy et al., 2014), which consists of low energy availability, menstrual disorders, and decreased bone density. The Triad is associated with additional health concerns (e.g., cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal, and bone stress injury) even in athletes who do not have a clinical ED (De Souza & Williams, 2004; Rauh, Nichols, & Barrack, 2010; Tenforde et al., 2017). Notably, in 2014, the International Olympic Committee updated the “Triad” to a more comprehensive syndrome: relative energy deficiency in sport (Mountjoy et al., 2018); however, because the present study was initiated before this update, this study targeted the Triad in addition to ED risk factors and symptoms.

The common occurrence of EDs in FA populations calls for additional treatment development efforts to address the unique needs of FAs with EDs. However, even the most efficacious ED interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and family-based therapy, leave many individuals symptomatic (Brownell & Walsh, 2017; Keel & Herzog, 2004; Wonderlich, Mitchell, Swan-Kreimer, Peterson, & Crow, 2004). Given how closely related ED behaviors are with symptoms of the Triad, interventions targeting ED risk factors (e.g., dietary restraint, thin-ideal internalization) offer a promising avenue for reducing onset of both EDs and the Triad in FAs, and may be a more cost-effective approach than treatment (Stewart et al., 2017; Wonderlich et al., 2004). Importantly, athletic departments/organizations can be key allies in the implementation of such risk factor reduction/prevention programs, given their vested interest in maintaining FAs’ health for ethical/performance reasons and the infrastructure necessary to support prevention programming.

Unfortunately, most FA ED prevention (or risk factor reduction) programs have shown limited effects on empirically supported ED risk factors (Bar, Cassin, & Dionne, 2016). Yet, two programs (Becker, McDaniel, Bull, Powell, & McIntyre, 2012; Martinsen et al., 2014) have produced long-term effects in ED symptoms or risk factors with FAs. Martinsen and colleagues found that a 1-year program targeting elite high school FAs reduced both onset of EDs and dieting at 9-month follow-up. Becker and colleagues investigated whether two much shorter 4-hr interventions (i.e., a dissonance intervention and a healthy weight intervention), with previously demonstrated efficacy and effectiveness in nonathlete populations, could be modified for FAs in a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Results indicated both interventions reduced ED symptoms in FAs (N = 157), as well as two risk factors (i.e., shape concern and negative affect), at 1-year follow-up when delivered by peers (i.e., cost-effective lay providers). Although no quantitative differences were found between the two interventions, qualitative feedback indicated the healthy weight intervention, which targeted healthy eating, was preferred over the dissonance intervention, which focused more on body image (Becker et al., 2012).

As noted by Bar and colleagues (Bar et al., 2016), larger trials with longer follow-ups are needed for programs that demonstrate positive results. The aim of the present RCT was to replicate and extend the preliminary results from the pilot/feasibility study conducted by Becker et al. (2012) using a larger sample and a longer follow-up. The core intervention (i.e., the Female Athlete Body project [FAB]), a behavioral ED risk factor reduction program, is based on the healthy weight intervention studied in Becker et al. (2012).

Many athletics departments have reported a desire to implement FAB with full teams and using peer-leaders. Per community-based participatory research methods, which give stakeholders a voice in designing research, the present study tested FAB: (a) when teams, versus individuals, were randomized to condition, and (b) using peer-leaders as intervention facilitators. This trial is best conceptualized as a hybrid between efficacy and effectiveness RCT methods due to the increased external validity provided by these two methodological decisions. To our knowledge, this study represents the largest existing RCT for FAs aimed at both ED prevention and reduction of risk factors, including ED symptoms such as binge eating.

The present analyses examine the outcomes of the FAB study. Details of the study rationale and design, data collection methods, and study sample baseline characteristics may be found in Stewart et al. (2017). We hypothesized that FAB would outperform the control condition in (a) reducing ED symptoms, ED risk factors, onset of new ED cases, and healthcare utilization and (b) increasing Triad knowledge. We did not predict differences in body mass index (BMI).

2 |. METHOD

2.1 |. Study design and randomization

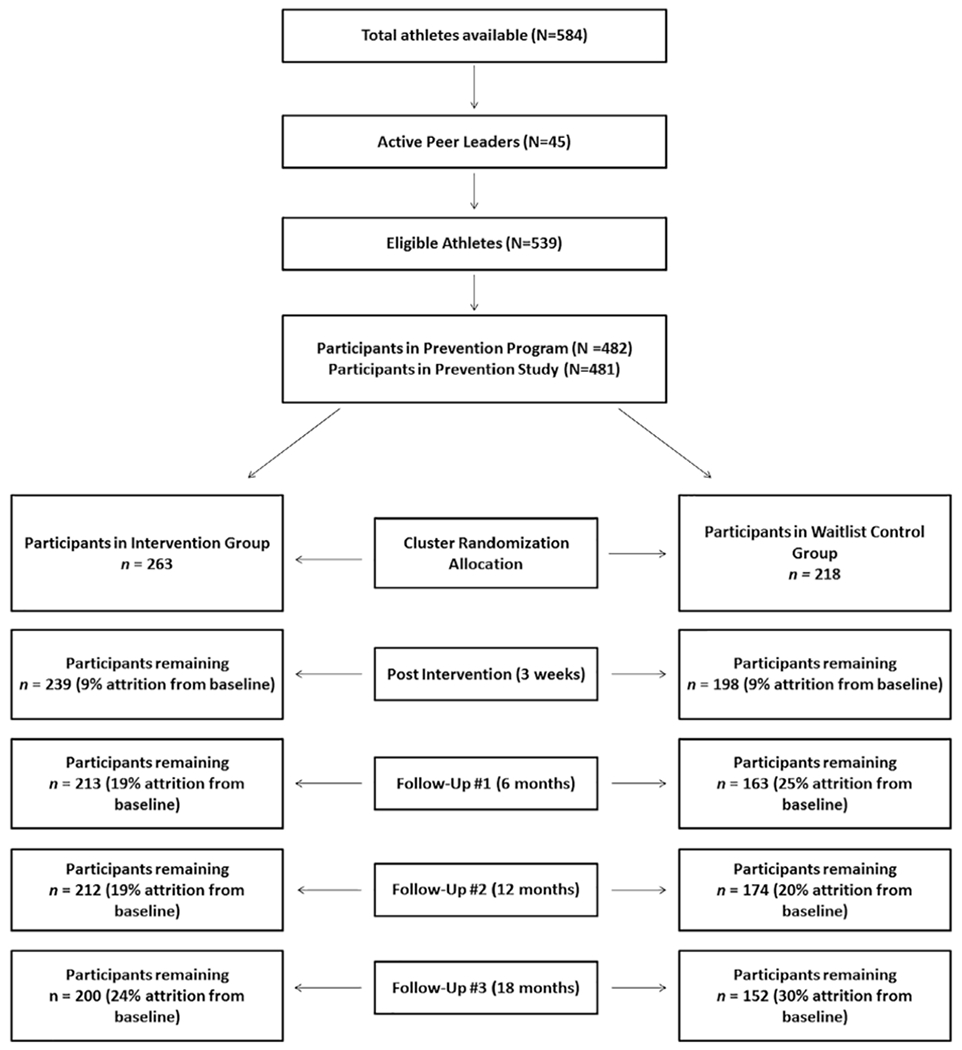

The study consisted of a United States-based, three-site (Baton Rouge, LA; San Antonio, TX; and Washington, DC) parallel-group RCT (Figure 1) comparing FAB to a waitlist control group. The FAB condition consisted of one peer-led 1.3-hr session per week over a 3-week period. Participants in the waitlist condition received a brochure at baseline with information about the Triad. Follow-up assessments were conducted for both groups at 3 weeks (postintervention for FAB participants), and at 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-up. Teams were randomly assigned to condition (i.e., FAB or waitlist control). Cluster randomization was stratified by sport, sport type (higher risk sports for EDs based on literature (e.g., aesthetic [e.g., gymnastics] and endurance sports [e.g., cross country]) and lower risk sports (e.g., ball game sports [e.g., softball, basketball]), and team size using the SAS procedure PROC PLAN. The study was completed in 2016. For a full list of teams and numbers of athletes from each team included in the study, see Stewart et al. (2017).

FIGURE 1.

Extended consort diagram: Participant flow

2.2 |. Ethics

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Pennington Biomedical Research Center (coordinating center, Baton Rouge, LA) and the partner sites. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants younger than 18 provided assent and then reconsented when they turned 18; this procedure was approved by all IRBs. Each participant could earn up to $250 in the study by answering questionnaires ($20) and phone interviews ($30) at each of the five time points over the course of 18 months. This incentive was necessary given the time constraints and motivation of busy student-athletes. A data and safety monitoring board provided study oversight.

2.3 |. Participant recruitment

Participants included university FAs, aged 17–27 years (mean age = 19 years). To reduce coercion, study staff recruited participants in the absence of athletics staff at prearranged team meetings. Study staff informed athletes that study participation was both anonymous and voluntary (Stewart et al., 2017). Athletes were informed that coaches and athletics staff would not learn which athletes participated or declined. Study enrollment began in August 2012 and completed in October 2014.

2.4 |. Procedure

Because the athletic departments wanted all athletes to complete FAB unless granted an excused absence by an athletic trainer, participation in the FAB program was separated from participation in the study, which consisted solely of completing the questionnaires and interviews. While all athletes participated in the FAB program and/or received the brochure, only those who opted in and provided consent completed the study portion (i.e., questionnaires and interviews). All athletes could complete the FAB intervention and choose to opt out of the study prior to beginning the groups, or drop out of the study at any time. This is consistent with community participatory research methods and previous trials of this kind (e.g., Becker et al., 2012). See Stewart et al. (2017) for additional discussion.

Athletes who did not attend group follow-up data collection either met with study staff individually or completed measures electronically. Those unable to be contacted were recorded as missing at each time point only, as some participants returned at later follow-up points.

To the greatest degree possible, initial groups were conducted off-season to respect the demanding schedules of athletes in season. However, depending on when that occurred, follow-up data collection sometimes occurred in season. Because data collection occurred every 6 months for all teams across both conditions, some assessments occurred during season and others during off-season.

2.5 |. Study assessments

Self-report demographic, questionnaire, and interview data were collected at baseline, 3 weeks (postintervention), and 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-up. ED symptoms were assessed with the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994) and the eating disorder examination interview (EDE; Sysko, Walsh, & Fairburn, 2005). Internalization was assessed by the ideal-body stereotype scale-revised (IBSS-R; Stice, Fisher, & Martinez, 2004) and the internalization of sport-specific thin-ideal scale (Stewart et al., 2017). The sadness, guilt, and fear/anxiety subscales of the positive and negative affect scale-revised (PANAS-X; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) assessed negative affect.

Other measures included BMI calculated from self-reported height and weight, knowledge of the female athlete triad questionnaire (Stewart et al., 2017), and the health survey utilization scale (Lane & Addis, 2005). We acknowledge the limitations of self-reported height and weight; however, it was not practical to capture objective BMI given study design, which was heavily influenced (per community participatory research methods) by the partnering athletics departments. As noted above, to meet demands by the partnering athletics departments, participation in the program was separated from study participation because the departments wanted teams to participate as cohesive units. To address accompanying ethical issues related to possible coercion to participate in the study with such a design, we made every effort to minimize potential coercion (e.g., telephone interviews with a blind assessor; completing questionnaire packets with backs turned). Collecting weight in person (even via remote scales at each study site) would have compromised athletes’ anonymity in opting into the study or not. Moreover, two athletics departments did not want us to violate policies that only allow medical staff to weigh athletes, and having medical staff provide weights would have violated the critical anonymity of the study. Thus, due to (a) the logistics of multisite research, (b) the compromises required by community participatory methods (which gave athletic departments a voice in the research design), and (c) efforts to maximize anonymity of athlete participants, we used self-reported height and weight. Intervention fidelity (i.e., adherence to manual and competence) was assessed via audio-recording of FAB intervention sessions by peer leaders. Both adherence and competence were deemed acceptable (Stewart et al., 2017).

2.6 |. Intervention

FAB is an interactive, small-group, discussion-based, three-session manualized intervention that encourages participants to strive for the athlete-specific healthy ideal (defined as the way one’s body appears when one is appropriately striving to simultaneously maximize physical and mental health, quality of life, and athletic performance) instead of an idealized body type. Key components of FAB include identifying differences between the healthy-ideal versus societal and sport-specific thin-ideals; education regarding the Triad, nutrition, the importance of balancing caloric input and output, sleep, and exercise; self-identifying healthy and unhealthy behaviors; goal setting; and body image exercises.

FAB encourages FAs to make small behavioral changes to achieve and maintain a healthy energy balance. Nutrition information was not sport-specific, but rather included encouragement to increase the nutrient density of meals and healthy eating when traveling to competitions. The nutrition components of the intervention were reviewed and approved by a NCAA Division I sports dietician prior to the initiation of this study. In addition to the mirror exercise, the body image exercises involved practicing responding to locker room “fat talk” and writing a letter to a younger teammate encouraging her to pursue her athlete-specific healthy-ideal instead of a sport-specific thin ideal (see Becker et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2017 for additional detail).

In this trial, FAB was delivered via trained peer-leaders. Peer-leaders at each study site were selected by coaches and/or head athletic trainers based on perceived reliability, leadership skills, and potential to be good role models. Each intervention group was run by at least one peer-leader from the same sport team as group participants, along with 1–2 peer-leaders from a different sport at the same university. Peer-leaders underwent two 4-hr experiential training sessions (see Stewart et al., 2017 for details). Teams of 2–3 peer-leaders delivered one 80-min group session per week for 3 weeks. Those in the wait-list condition received an educational brochure on the Triad. After the conclusion of the RCT, control teams were offered FAB at the discretion of the athletic departments.

2.7 |. Statistical analysis

For the a priori power analysis, intervention effect sizes were estimated, where unstandardized treatment effect (b) is divided by the pooled within-group SD at the end of treatment. Power analysis calculations were based on EDE-Q global score, thin-ideal internalization, and body dissatisfaction using data from Becker et al. (2012) and Stice, Shaw, Burton, and Wade (2006). We considered the design effect of 1.5, or the intraclass correlation (ICC) of .03 in the power calculations for the group randomization design. Power calculations were performed for a two-sided Type I error rate of 0.05, assuming a complete balance design. Statistical power was >0.80 for the outcomes assuming 10% attrition and α = .05 with 28 teams averaging 19 members and an ICC coefficient = .03 to detect Cohen’s d effect sizes ≥0.35.

To assess 18-month outcomes using intent to treat analyses, we used linear mixed effects models with random intercept and slope, with team as the cluster level variable (N = 28), intervention as a between-subjects (Level 2) variable, and latent growth over the 18-month study duration as a within-subject (Level 1) variable. We used assessments at baseline, 6-, 12-, and 18-months. Intervention effects were estimated as the between-level effects of the intervention on change at 18-months (slope differences for entire study period) with α = .05. Time was coded at 0, 0.33 (6/18), 0.66 (12/18), and 1 (18/18) so that the model estimated slope represented difference between groups at 18-month follow-up. Missing data were assumed to be missing at random, so all models use full-information maximum likelihood estimates, which included all observed data in the models. We used a maximum likelihood estimator for all models and estimated mean and SEs for all parameters of interest, unless there was evidence of variable skew, in which case we used robust maximum likelihood. Intervention effect sizes were estimated, where unstandardized treatment effect (b) is divided by the pooled within-group SD at the end of treatment and is equivalent to Cohen’s d for growth curve models.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Participant flow

Participants included 481 FAs (FAB group, n = 263, control group, n = 218). There were no significant differences between FAB and control groups on age (M = 19.4, p = .262), height (M = 66.1, p = .618), weight (M = 139.9, p = .969), race and ethnicity frequencies, or levels of parental education. See Stewart et al. (2017) for further demographic detail and original baseline consort data (Schulz et al., 2010). Of the 263 participants in the FAB group, 255 received the full intervention; attrition resulted from participants leaving their team or being removed from their sport by an athletic trainer prior to intervention completion (see Figure 1 for an extended consort diagram).

3.2 |. Primary outcomes

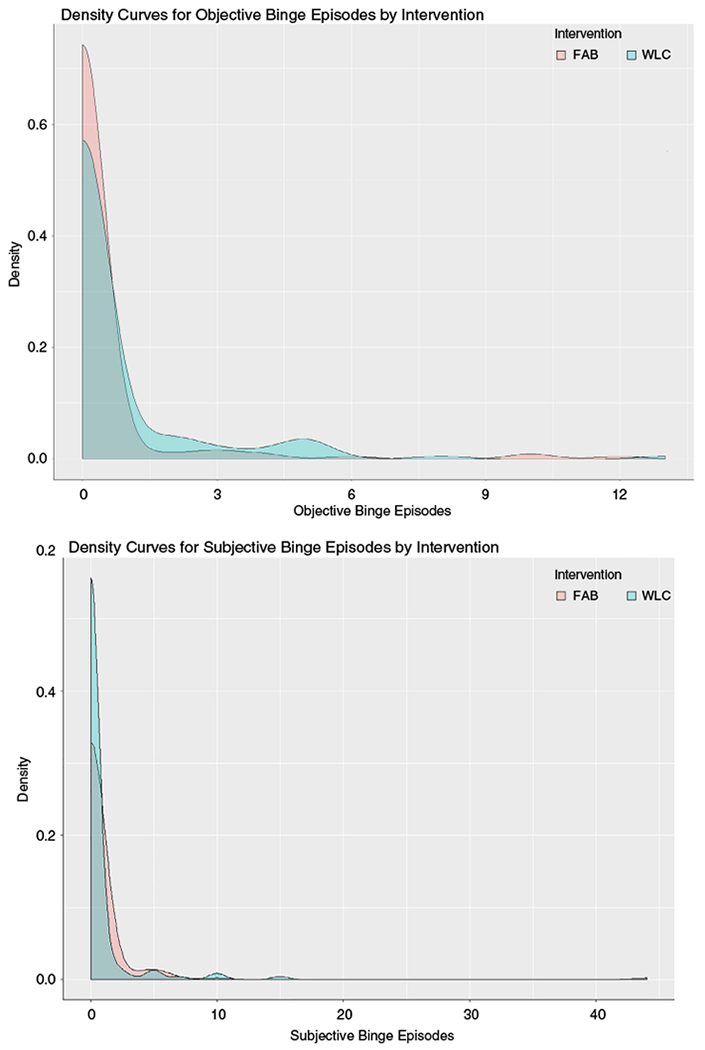

Tables 1 and 2 summarize 18-month outcome effects for EDE-Q subscales and specific ED behaviors. Although the direction of EDE-Q effect sizes all favored FAB compared to control and ranged from −1.34 to −0.06, the only significant subscale effect emerged for dietary restraint. Teams randomized to FAB also reported significantly fewer objective binge episodes (OBEs) and subjective binge episodes (SBEs) at 18 months, although abstinence rates did not differ between groups. Inspection of density curves for both outcomes indicated that differences were largely related to greater density of those with 1–2 OBEs per month in FAB, in contrast to greater spread of OBE counts in the control group (Figure 2). There was no significant intervention effect on change in ED diagnosis or compensatory behaviors based on the EDE-Q.

TABLE 1.

Summary of EDE-Q multilevel mixed effects models over 18-month follow-up

| EDE-Q | Baseline | 18-month | Mean difference | d | ICC slope | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAB | WLC | FAB | WLC | ||||

| Global | 1.24 (0.22) | 1.40 (0.22) | 0.98 (0.17) | 1.24 (0.16) | −0.10 (0.09) | −0.61 | .12 |

| Restraint | 0.61 (0.11) | 0.71 (0.18) | 0.54 (0.11) | 0.84 (0.18) | −0.20 (0.11)a | −1.34 | .08 |

| Shape concern | 1.38 (0.19) | 1.66 (0.28) | 1.13 (0.21) | 1.46 (0.28) | −0.05 (0.12) | −0.20 | .01 |

| Weight concern | 1.18 (0.24) | 1.30 (0.25) | 1.03 (0.26) | 1.17 (0.24) | −0.03 (0.11) | −0.16 | .02 |

| Eating concern | 0.53 (0.08) | 0.58 (0.10) | 0.49 (0.16) | 0.55 (0.15) | −0.01 (0.09) | −0.06 | .02 |

Note: FAB n = 263, WLC n = 218. The numbers in parentheses indicate SE.

Abbreviations: EDE-Q, eating disorder examination questionnaire; FAB, Female Athlete Body project; ICC, intraclass correlation; WLC, waitlist control.

Significant values, p < .05, for condition by time interaction.

TABLE 2.

Summary of multilevel mixed effects models for behavioral outcomes over 18-month follow-up

| EDE-Q | Baseline | 18-month | Mean difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAB | WLC | FAB | WLC | ||

| OBE frequency | 0.65 (2.71) | 0.91 (4.96) | 0.35 (1.56) | 0.63 (1.75) | −1.11 (0.48)a |

| No OBEs | 86.33% | 85.65% | 92.66% | 83.33% | 0.77 (0.56) |

| SBE frequency | 0.91 (3.39) | 0.81 (2.68) | 0.49 (1.94) | 0.57 (3.52) | −1.63 (0.70)a |

| No SBEs | 82.03% | 82.78% | 92.66% | 89.58% | −0.43 (0.51) |

| No compensatory behavior | 95.31% | 91.87% | 95.48% | 92.36% | −2.24 (0.13) |

| ED diagnoses | 13.31% | 12.84% | 5.70% | 12.24% | −0.79 (0.53) |

Note: FAB n = 263, WLC n = 218. The numbers in parentheses indicate SE.

Abbreviations: ED, eating disorder; EDE-Q, eating disorder examination questionnaire; FAB, Female Athlete Body project; OBE, objective binge episode; SBE, subjective binge episode; WLC, waitlist control.

Significant values, p < .05, for condition by time interaction.

FIGURE 2.

Density curves for objective and subjective binge episodes by intervention arm. Density curves for both objective and subjective binge eating show that 18-month differences emerged between groups primarily because higher density of individuals reporting binge episodes among those who were binge eating

Because FAB was conceptualized as an ED prevention program (not a treatment), we tested whether or not FAB reduced onset of EDs (i.e., development of new EDs during the trial) in those who did not meet criteria for an ED at baseline relative to the control condition. Development of new EDs, as measured by the EDE-Q, was 6.77% (n = 15/222) in FAB and 9.57% for the control (n = 18/188). This difference was not significant in the mixed effects model, which weighted differences by team to account for the cluster-randomized nature of this trial. Notably, levels of compensatory behaviors (e.g., vomiting, laxative use) in this sample were very low even when all compensatory behaviors were combined, thus raising the possibility of floor effects.

We chose to not analyze EDE results for several reasons. First, data from the EDE interviews were substantially less complete (i.e., more missing data including at baseline). Second, response patterns suggested unrealistically low scale score and symptom reports, raising concerns about accuracy. Finally, despite asking participants to conduct the phone interview in a private setting where they would be free to discuss very personal issues, ambient background noise observed by the interviewer suggested that many participants disregarded this instruction. Thus, the phone interviewer questioned the validity of participant responses in public settings. In summary, the research team, including the statistician, concluded that, taken as a whole, the EDE data were sufficiently flawed that it was not appropriate to analyze those data.

3.3 |. Secondary outcomes

Secondary 18-month outcomes demonstrated a similar pattern (see Tables 3 and 4). FAB teams demonstrated reduced thin-ideal internalization through IBSS-R scores (d = −2.72). Control condition teams reported greater knowledge in the Triad (d = −0.89). This seems to be driven by a small but statistically significant decrease in knowledge in the FAB group. No other significant effects on secondary outcomes emerged, with the exception of BMI. FAB teams demonstrated a significantly greater increase in BMI at 18 months. We examined interactions between BMI and primary eating pathology (EDE-Q) outcomes and found evidence that FAB participants with higher BMI’s had greater improvements in EDE-Q shape concern scores (β = −.05, SE = 0.02, p < .05, 95% CI [−0.09, −0.01]); these athletes also accounted for the FAB increase in BMI. More specifically, female athletes with BMIs over 27 gained more weight in FAB (β = −.05, SE = 0.02, p < .008, 95% CI [−0.012, 0.083]). No other interactions were significant.

TABLE 3.

Summary of multilevel mixed effects models for secondary outcomes over 18-month follow-up

| Baseline | 18-month | Mean difference | d | ICC slope | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAB | WLC | FAB | WLC | ||||

| ISTI | 2.45 (0.18) | 2.68 (0.30) | 2.46 (0.18) | 2.71 (0.31) | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.08 | .15 |

| BMI | 24.14 (1.12) | 23.84 (0.90) | 25.09 (1.12) | 24.22 (0.90) | 0.57 (0.29)a | 0.56 | .01 |

| TRH | 31.46 (0.63) | 31.58 (0.84) | 30.28 (0.65) | 29.87 (0.85) | 0.48 (0.73) | 0.63 | .16 |

| IBSS-R | 3.47 (0.06) | 3.56 (0.06) | 3.20 (0.06) | 3.43 (0.05) | −0.15 (0.07)a | −2.72 | .02 |

| PANAS | 1.59 (0.04) | 1.64 (0.05) | 1.50 (0.04) | 1.59 (0.06) | −0.04 (0.06) | −0.78 | .01 |

| ISE | 29.47 (5.72) | 25.74 (6.25) | 29.92 (7.80) | 26.50 (8.52) | −0.37 (1.02) | −0.05 | .08 |

| KFAT | 8.77 (0.37) | 8.52 (0.28) | 8.54 (0.37) | 8.58 (0.30) | −0.30 (0.14)a | −0.89 | .07 |

Note: FAB n = 263, WLC n = 218. Numbers in parentheses indicate SE.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FAB, Female Athlete Body project; IBSS-R, ideal-body stereotype scale—revised; ICC, intraclass correlation; ISE, intervention suitability expectations; ISTI, internalization of the sport-specific thin-ideal; KFAT, knowledge of the female athlete triad; PANAS, positive and negative affect scale—revised; TRH, teammate relationship health; WLC, waitlist control.

Significant values at p < .05, for condition by time interaction.

TABLE 4.

Summary of multilevel mixed effects models for healthcare utilization over 18-month follow-up

| Baseline | 18-month | Mean difference | d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAB | WLC | FAB | WLC | |||

| #Physical absence | 1.12 (0.14) | 1.03 (0.10) | 0.83 (0.19) | 0.67 (0.15) | 0.07 (0.17) | 0.58 |

| #Mental absence | 0.37 (0.13) | 0.29 (0.07) | 0.34 (0.14) | 0.32 (0.10) | −0.07 (0.16) | −0.67 |

| #Weight absence | 0.17 (0.01) | 0.16 (0.01) | 0.21 (0.05) | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.09 (0.09) | 1.8 |

| #Eating disorders absence | 0.12 (0.03) | 0.11 (0.01) | 0.20 (0.09) | 0.15 (0.06) | 0.06 (0.11) | 0.78 |

| #Other absence | 0.31 (0.05) | 0.32 (0.05) | 0.22 (0.06) | 0.26 (0.06) | −0.04 (0.13) | −0.67 |

Note: FAB n = 263, WLC n = 218. Numbers in parentheses indicate SE.

Abbreviations: FAB, Female Athlete Body project; WLC, waitlist control.

Type of sport has long been thought to influence ED risk. Thus, we investigated if type of sport (e.g., lean and nonlean) impacted results. There were 12 lean teams and 16 nonlean teams. This analysis was modeled as a fixed Level 2 effect in the same mixed model framework for the primary analyses. We found no effects for type of sport regardless of whether we compared lean versus nonlean or compared different sports (i.e., soccer, swimming, etc.). It is important to note that ability to detect this and other effects may have been influenced by the fact that individual teams demonstrated a very high degree of variability.

4 |. DISCUSSION

This study investigated the efficacy of the FAB program when implemented by peer-leaders. Primary outcomes did not fully support our hypotheses. For EDE-Q scales, only dietary restraint was significantly reduced for FAB relative to control. FAB also resulted in less frequent OBEs and SBEs at 18 months as assessed by the EDE-Q. Importantly, this is the first time a short (i.e., 4 hr) intervention has been found to reduce both binge eating and dieting in FAs at long-term follow-up. With regards to onset of EDs, the primary marker of true prevention, there was no significant intervention effect, although 18-month onset was lower for FAB than control. There also was no 18-month difference in compensatory behaviors; however, the low occurrence of compensatory behaviors in the sample may have resulted in floor effects. Nonetheless, aside from Martinsen et al. (2014), this is the only athlete study to date to show long-term reductions in any specific ED behavior. Furthermore, FAB is the only FA program to date to produce reductions in some ED risk factors in multiple trials at follow-up (Becker et al., 2012).

Regarding secondary outcomes, FAB yielded a greater reduction in the IBSS-R scores, a significant risk factor for the development of ED symptoms, compared to control. Participants in FAB also reported a greater increase in self-reported BMI at follow-up, and increased BMI was associated with greater improvements in shape concerns. A key focus of FAB is encouraging FAs to adequately fuel their bodies so as to reduce risk for the Triad. Increased BMI was associated with decreased shape concern over time, which indicates that FAB may have successfully improved some athletes’ ability to accept their bodies at higher weights. The finding that athletes with higher BMIs at baseline reported gaining more weight in FAB as compared to the control condition could be viewed either as an iatrogenic (if increased BMI indicates an unhealthy increase in adipose tissue) or a positive (if increased BMI indicates a healthy increase in adipose tissue or fat free mass) outcome. It is beyond the scope of this article to provide a detailed discussion of adiposity in athletes. Yet it is important to note that research indicates that BMI is not a good predictor of adiposity in athletes (Prentice & Jebb, 2001; Santos et al., 2015). As such, it is impossible to know how FAB affected body composition. This BMI finding also is significantly tempered by the well-known limitations of self-reported height and weight, and in need of replication using objectively measured height, weight, and body composition.

Contrary to our hypotheses, results indicated that control participants reported greater 18-month Triad knowledge. One possible explanation is that the control condition brochure allowed participants repeated access to Triad information. Since those in FAB were not provided with a comparable handout, it is possible that their knowledge faded. This suggests that future interventions should provide written information to participants. It is also conceivable that cross-contamination may have occurred between teams over the 18-month period; however, this is unlikely as athletes belonging to the same team were in the same condition and exposed to the same material. Thus, those most likely to discuss program content (i.e., teammates with each other) were all in the same condition.

The present trial has a number of limitations, several of which are linked to working with the sport community. First, this trial was designed as a cluster RCT to accommodate the community’s strong preference that FAB be delivered to intact teams. One strength of this design is that it reduces problems with diffusion of intervention (or contamination of the control group), which is highly probable if half of each team is randomized to a different condition. One problem with this design, however, is that it markedly reduces statistical power.

A related limitation is that we encountered significant team-based variability, which is likely a “coach effect.” More specifically, individual coaching philosophies and/or practices (including athlete characteristics recruited by coaches) can systematically influence variables investigated in this study. For example, whereas one coach may encourage athletes to pursue health, another may promote unhealthy practices aimed at weight loss; these team-based differences may in turn affect athletes’ response to interventions. If athletes were randomized individually, these effects would be dispersed across the two conditions. In a cluster RCT, however, this systematic variability reduces power to find effects. Although this study was powered to find effects based on assumptions of normal, random variability between randomized units (teams) and we randomized teams at multiple sites to minimize these types of effects, the trial was not powered to overcome the systemic, team-based variability we encountered. The implication for future trials is that researchers either need to convince athletic departments to allow individual-level randomization despite their team-based culture, or to significantly increase the number of participating teams with many more schools.

A third limitation is the possible role played by athletic medical staff. All study sites had excellent head athletic trainers, who reported striving to identify and intervene with athletes demonstrating ED symptomatology as part of routine practice. In some cases, this meant athletes left their sport and the trial. This selective attrition, based on active efforts by medical personnel, potentially violates the assumptions of the control model, which presumes the control condition represents the natural onset of the disorder. This could have contributed to decreased differences between conditions if more ED symptoms developed in the control group and were detected by skilled medical staff. The dilemma of a trial in a university athletics community is that it requires supportive and efficient athletic departments; however, the athletic departments’ strong ability to aid athletes struggling with ED symptomology may inherently challenge examination of these same variables in studies. Unfortunately, because participants in this trial completed assessments using self-generated IDs to maintain anonymity, we cannot determine whether or not trainers intervened to an equivalent degree with athletes in both conditions. A related limitation to this is that we did not conduct a dropout analysis.

A final limitation involved missing and suspect EDE-interview data, which precluded usage in our analyses. This study used community participatory methodology, which was crucial in getting athletic department buy-in. As such, we utilized phone interviews, which were strongly preferred over in-person interviews by participating athletics departments to increase anonymity; however, many athletes chose convenient, rather than private, spaces to complete the interviews, despite being instructed to do otherwise. Thus, many phone interviews appeared to take place (based on ambient noise) in public locations where conversations could be overheard, which we suspect influenced the participants’ honesty. Future athlete trials may benefit from considering alternative interview methods that maintain high levels of anonymity while simultaneously ensuring greater honesty.

In sum, this trial highlights some of the methodological challenges in conducting prevention/risk-factor reduction trials with university FAs. Despite the rather conservative nature of the trial (e.g., cluster randomized and use of community peer-leaders), the trial did provide support for FAB. No other intervention as short as FAB has significantly impacted any ED symptoms or risk factors through 18-month follow-up in FAs. Future trials might benefit from the following: (a) FAB delivery using clinical providers, who might produce larger effects given the complexity of FA body image and demands of athletic performance, (b) randomization by individual athlete (instead of team), (c) even larger samples with more teams at more schools, and finally, (d) an auxiliary intervention for coaches.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The present research study was supported by grant NIMH 1 R01 MH094448-01A1 from the National Institute of Mental Health. We would like to acknowledge the team of people (investigators, project managers, student workers, departments of athletics) who contributed to this research including but not limited to: (a) Pennington Biomedical Research Center: Heather Walden, Shelly Ragusa, Ray Allen, Archana Archarya, Hongmei Han, Lindsay Hall; (b) Louisiana site: Shelly Mullenix, Miriam Seger, Jamie Mascari Meeks; (c) Texas sites: Marc Powell, Christina Verzijl; and (d) District of Columbia site: Kelly MacKenzie, Athena Argyropoulos, Jonathon Tubman. We would also like to offer sincere thanks to our senior consultants on the research program including G. Terrence Wilson, PhD and Ron Thompson, PhD.

Funding information

National Institute of Mental Health, Grant/Award Number: NIMH 1 R01 MH094448-01A1

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Becker currently serves as a codirector of the Body Project Collaborative, a company that facilitates implementation of prevention programs in nonathletes.

REFERENCES

- Bar RJ, Cassin SE, & Dionne MM (2016). Eating disorder prevention initiatives for athletes: A review. European Journal of Sport Science, 16 (3), 325–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, McDaniel L, Bull S, Powell M, & McIntyre K (2012). Can we reduce eating disorder risk factors in female college athletes? A randomized exploratory investigation of two peer-led interventions. Body Image, 9(1), 31–42. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, & Walsh BT (Eds.). (2017). Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carta M, Preti A, & Moro M (2014). Eating disorders as a public health issue: Prevalence and attributable impairment of quality of life in an Italian community sample. International Review of Psychiatry, 26, 486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow S (2014). The economics of eating disorder treatment. Current Psychiatry Reports, 16(7), 454 10.1007/s11920-014-0454-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza M, & Williams N (2004). Physiological aspects and clinical sequelae of energy deficiency and hypoestrogenism in exercising women. Human Reproduction Update, 10(5), 433–448. 10.1093/humupd/dmh033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Beglin SJ (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton P (2005). Running on empty. Training and Conditioning, 15(6), 11–18 Retrieved from http://www.training-conditioning.com/2007/03/running_on_empty.html [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr., & Kessler RC (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348–358. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy E, Kussman A, & Nattiv A (2017). 2016 update on eating disorders in athletes: A comprehensive narrative review with a focus on clinical assessment and management. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50, 154–162. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, & Herzog DB (2004). Long-term outcome, course of illness and mortality in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder In Brewerton TD (Ed.), Clinical handbook of eating disorders (pp. 97–116). New York: Marcel Dekker. [Google Scholar]

- Kong P, & Harris LM (2015). The sporting body: Body image and eating disorder symptomatology among female athletes from leanness focused and nonleanness focused sports. The Journal of Psychology, 149(2), 141–160. 10.1080/00223980.2013.846291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JM, & Addis ME (2005). Male gender role conflict and patterns of help seeking in Costa Rica and the United States. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6(3), 155–168. 10.1037/1524-9220.6.3.155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen M, Bahr R, Borresen R, Holme I, Pensgaard A, & Sundgot-Borgen J (2014). Preventing eating disorders among young elite athletes: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 46(3), 435–447. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182a702fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Ackerman KE, Blauwet C, Constantini N, & Budgett R (2018). International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 28(4), 316–331. 10.1123/ijsnem.2018-0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen J, Burke L, Carter S, Constantini N, Lebrun C, … Ljungqvist A (2014). The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the female athlete triad-relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(7), 491–497. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice AM, & Jebb SA (2001). Beyond body mass index. Obesity Reviews, 2(3), 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh MJ, Nichols JF, & Barrack MT (2010). Relationships among injury and disordered eating, menstrual dysfunction, and low bone density in high school athletes: A prospective study. Journal of Athletic Training, 45(3), 243–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos DA, Silva AM, Matias CN, Magalhaes JP, Minderico CS, Thomas DM, & Sardinha LB (2015). Utility of novel body indices in predicting fat mass in elite athletes. Nutrition, 31(7–8), 948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, & CONSORT Group. (2010). CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ, 340, c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart T, Pollard T, Hildebrandt T, Beyl R, Wesley N, Kilpela LS, & Becker CB (2017). The Female Athlete Body (FAB) study: Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 60, 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Fisher M, & Martinez E (2004). Eating disorder diagnostic scale: Additional evidence of reliability and validity. Psychological Assessment, 16(1), 60–71. 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Burton E, & Wade E (2006). Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: A randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 263–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Walsh BT, & Fairburn CG (2005). Eating disorder examination-questionnaire as a measure of change in patients with bulimia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 37(2), 100–106. 10.1002/eat.20078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenforde AS, Carlson JL, Chang A, Sainani KL, Shultz R, Kim JH, … Fredericson M (2017). Association of the female athlete triad risk assessment stratification to the development of bone stress injuries in collegiate athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(2), 302–310. 10.1177/0363546516676262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, & Sherman RT (Eds.). (2010). Eating disorders in sport. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich S, Mitchell J, Swan-Kreimer L, Peterson C, & Crow S (2004). An Overview of Cognitive-Behavioral Approaches to Eating Disorders In Brewerton TD (Ed.), Clinical handbook of eating disorders (pp. 405–426). New York: Marcel Dekker. [Google Scholar]