Abstract

Introduction

Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg is a novel glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) that, in the SUSTAIN clinical trials, has demonstrated greater reductions in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and body weight than the other GLP-1 RAs exenatide extended-release (ER) 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg. The aim of this analysis was to evaluate the relative cost of control of achieving treatment goals in people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) treated with once-weekly semaglutide versus exenatide ER, dulaglutide and liraglutide from a UK perspective.

Methods

Proportions of patients reaching HbA1c targets (< 7.0% and < 7.5%), weight loss targets (≥ 5% reduction in body weight) and composite endpoints (HbA1c < 7.0% without weight gain or hypoglycaemia; reduction in HbA1c of ≥ 1% and weight loss of ≥ 5%) were obtained from the SUSTAIN clinical trials. Annual per patient treatment costs were based on wholesale acquisition costs from July 2019 in the UK. Cost of control was calculated by plotting relative treatment costs against relative efficacy.

Results

The annual per patient cost was similar for all GLP-1 RAs. Once-weekly semaglutide was superior to exenatide ER, dulaglutide and liraglutide in bringing patients to HbA1c and weight loss targets, and to composite endpoints. When looking at the composite endpoint of HbA1c < 7.0% without weight gain or hypoglycaemia, exenatide ER, dulaglutide and liraglutide were 50.0%, 21.6% and 51.3% less efficacious in achieving this, respectively, than once-weekly semaglutide. Consequently, the efficacy-to-cost ratios for once-weekly semaglutide were superior to all comparators in bringing patients to all endpoints.

Conclusions

The present study showed that once-weekly semaglutide offers superior cost of control versus exenatide ER, dulaglutide and liraglutide in terms of achieving clinically relevant, single and composite endpoints. Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg would therefore represent good value for money in the UK setting.

Electronic Supplementary Material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-020-01242-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cost-effectiveness, Cost of control analysis, Diabetes, Economic evaluation, Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, Semaglutide, Type 2 diabetes

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is associated with a significant clinical and economic burden in the UK |

| In order to manage and allocate healthcare budgets, the UK National Health Service (NHS) relies on value-based decisions to ensure that funded interventions represent good value for money |

| The aim of this analysis was to evaluate, from a UK perspective, the relative cost of achieving treatment goals in people with T2D treated with once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg versus the glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists exenatide extended-release (ER) 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The present study showed that once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg offers superior cost of control versus exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg in terms of achieving clinically relevant, single and composite endpoints |

| Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg would therefore represent good value for money in the UK |

Introduction

Diabetes is associated with a significant clinical and economic burden in the UK. Approximately 6% of the UK population are affected by diabetes, 90% of whom have type 2 diabetes (T2D) [1, 2]. Diabetes is associated with significant microvascular and macrovascular complications, and every week in the UK around 500 people with diabetes die prematurely [2, 3]. The prevention and treatment of diabetes, together with the burden of managing related complications, are associated with a high financial burden; in 2017, diabetes-related healthcare expenditure exceeded GBP 10 billion [1]. Diabetes, its comorbidities and the requirement for monitoring and management also result in a considerable humanistic burden and reduced quality of life [4]; diabetes is the leading cause of blindness in people of working age in the UK, and each week over 100 amputations are carried out on people with diabetes [2, 3, 5–7].

Reductions in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), an indicator of glycaemic control, are associated with a lowered risk of long-term diabetes complications [8–10]. However, treatments that can lower blood glucose levels and reduce HbA1c are associated with an inherent risk of hypoglycaemia. Severe hypoglycaemia can increase the risk of cardiovascular complications and all-cause mortality [11], as well as negatively affect patients’ well-being [12, 13]. For this reason, treatments with a low risk of hypoglycaemia may be of value to people with diabetes. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends a target HbA1c of ≤ 6.5%, ≤ 7.0% or less stringent thresholds for people with T2D, depending on the individual patient requirements and their risk of hypoglycaemia [14]. However, in a 2016–2017 audit of England and Wales, only 67% of people with T2D or other types of diabetes (excluding type 1 diabetes) were found to achieve target HbA1c levels of ≤ 7.5% [15]. Reduction in body weight is also associated with a lower long-term risk of complications; consequently, NICE recommends a weight loss target of 5–10% for patients above a healthy weight [14, 16, 17]. Therefore, a triple composite target of HbA1c < 7.0% without weight gain and without hypoglycaemia can be considered a key metric when assessing quality of care. The target of HbA1c < 7.0% was chosen on the basis of the American Diabetes Association’s (ADA’s) clinical practice guidelines because these are well recognized globally [18]. Management strategies to achieve this composite endpoint have the potential to both reduce costs and improve quality of life [8–10, 14, 16].

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are a class of highly effective diabetes therapies that are associated with improved glycaemic control, reductions in body weight and a low hypoglycaemia risk [19]. Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg (Ozempic®; Novo Nordisk A/S) is a novel GLP-1 RA that, throughout the SUSTAIN clinical trial programme, has demonstrated greater reductions in HbA1c and body weight than the other GLP-1 agonists exenatide extended-release (ER) 2 mg (Byetta®; AstraZeneca) [20], dulaglutide 1.5 mg (Trulicity®; Eli Lilly) [21] and liraglutide 1.2 mg (Victoza®; Novo Nordisk A/S) [22]. Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg was granted marketing authorisation in 2018 for use in adults with insufficiently controlled T2D as an adjunct to diet and exercise by the European Medicines Agency [23]. According to current guidance from the NICE, GLP-1 RAs are recommended for patients with T2D and obesity if triple therapy with metformin and two other oral drugs is not effective, not tolerated or contraindicated [14].

The UK National Health Service (NHS) relies on value-based decisions to manage and allocate healthcare budgets and ensure that funded interventions represent good value for money [24, 25]. In a recent long-term analysis, once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg was found to be cost-effective for the treatment of T2D in the UK, compared with dulaglutide 1.5 mg [26]. Short-term economic analyses, such as cost of control analyses, complement longer-term analyses and are useful to assess and easily compare the cost-effectiveness of multiple new treatments. Cost of control analyses are easy to conduct and interpret, and can be readily repeated for different comparators and from different perspectives. In recent cost of control analyses, once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg showed favourable cost-effectiveness compared with exenatide ER 2 mg and dulaglutide 1.5 mg in the USA and in Canada [27, 28], and compared with dulaglutide 1.5 mg, exenatide ER 2 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg and insulin glargine U100 in the UK [29].

The aim of this analysis was to evaluate, from a UK perspective, the relative cost of control of achieving treatment targets in people with T2D treated with once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg versus exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg.

Methods

Clinical Data

Published clinical data for the analysis were taken from the SUSTAIN 3 [20], SUSTAIN 7 [21] and SUSTAIN 10 [22] trials, which compared once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg with exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg, respectively. In addition to GLP-1 RAs, patients received 1–2 oral antidiabetic drugs in SUSTAIN 3, metformin in SUSTAIN 7 and 1–3 oral antidiabetic drugs in SUSTAIN 10. These comparators were chosen in order to compare once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg with GLP-1 RAs that are widely available in the UK.

The analysis was based on the proportion of patients from the SUSTAIN trials achieving the following target endpoints with each intervention:

HbA1c ≤ 6.5%, < 7.0% and < 7.5%

Weight loss ≥ 5% and ≥ 10%

Composite endpoints of HbA1c < 7.0% without weight gain and without hypoglycaemia, and a reduction in HbA1c of ≥ 1% with weight loss of ≥ 5%

The baseline characteristics of patients and the proportion of patients who achieved target endpoints included in the analysis are shown in Table 1. HbA1c < 7.5% was calculated in a post hoc analysis of the SUSTAIN trials, and the composite endpoint of a reduction in HbA1c of ≥ 1% with weight loss of ≥ 5% for once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg versus exenatide ER 2 mg was calculated in a post hoc analysis of SUSTAIN 3 [30]. The statistical significance of differences between treatments was assessed using a logistic regression model.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients and endpoints in SUSTAIN 3, SUSTAIN 7 and SUSTAIN 10

| SUSTAIN 3 | SUSTAIN 7 | SUSTAIN 10 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg | Exenatide ER 2 mg | Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg | Dulaglutide 1.5 mg | Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg | Liraglutide 1.2 mg | |

| Intent-to-treat population (n) | 404 | 405 | 300 | 299 | 290 | 287 |

| Treatment period (weeks) | 56 | 40 | 30 | |||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 56.4 | 56.7 | 55 | 56 | 60.1 | 58.9 |

| Duration of diabetes (years) | 9.0 | 9.4 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 9.6 | 8.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 34.0 | 33.6 | 33.6 | 33.1 | 33.7 | 33.7 |

| Baseline HbA1c (%) | 8.4 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 8.3 |

| Antidiabetic medications at screening (%) | ||||||

| Biguanides | 96.8 | 96.3 | 100 | 100 | 96.2 | 93.4 |

| Sulfonylureas | 44.8 | 51.4 | – | – | 46.9 | 46.7 |

| Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors | – | – | – | – | 25.2 | 24.0 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 3.2 | 1.5 | – | – | – | – |

| Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0.3* |

| Other blood glucose-lowering drugs (excluding insulin) | 0.2† | 0.5† | – | – | 0.3 | 0 |

| Long-acting insulins and analogues for injection | 0 | 0.2† | – | – | – | – |

| HbA1c endpoints | ||||||

| Change in HbA1c from baseline to end of trial (%) | – 1.5‡ | – 0.9 | – 1.8§ | – 1.4 | – 1.7¶ | – 1.0 |

| Proportion of patients achieving HbA1c ≤ 6.5% (%) | 47 | 22 | 67 | 47 | 58.5 | 24.8 |

| Proportion of patients achieving HbA1c < 7.0% (%) | 67 | 40 | 79 | 67 | 80.4 | 45.9 |

| Proportion of patients achieving HbA1c < 7.5% (%) | 78.2 | 58.0 | 88.0 | 78.3 | 92.5 | 67.6 |

| Weight loss endpoints | ||||||

| Proportion of patients achieving weight loss ≥ 5% (%) | 52 | 17 | 63 | 30 | 55.9 | 17.7 |

| Proportion of patients achieving weight loss ≥ 10% (%) | 21 | 4 | 27 | 8 | 19.1 | 4.4 |

| Composite endpoints | ||||||

| Proportion of patients achieving HbA1c < 7.0% without weight gain and without hypoglycaemia (%) | 56 | 28 | 74 | 58 | 75.6 | 36.8 |

| Proportion of patients achieving a ≥ 1% reduction in HbA1c and ≥ 5% weight loss (%) | 43 | 13 | 59 | 23 | 49.6 | 11.9 |

Values presented are means, unless stated otherwise

ER extended-release, HbA1c glycated haemoglobin

* Patients receiving dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and repaglinide were randomized in error and discontinued treatment

†Patients receiving other blood glucose-lowering drugs and long-acting insulins and analogues for injection were randomized in error and discontinued treatment

‡p < 0.0001 versus exenatide ER 2 mg

§p < 0.0001 versus dulaglutide 1.5 mg

¶p < 0.0001 versus liraglutide 1.2 mg

Cost Data, Resource Use, Time Horizon and Perspective of the Analysis

The analysis was conducted from the perspective of the NHS in 2019, with outcomes projected over a 1-year time horizon. For simplicity, only wholesale acquisition prices were used to calculate costs for each therapy at the recommended dose; UK prices were taken from the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS; sourced 19 July 2019; Table 2) [31]. Costs related to self-monitoring of blood glucose were assumed to be the same for each treatment regimen; therefore, these costs were not included. Costs for needles for once-weekly semaglutide 1.2 mg, exenatide ER 2 mg and dulaglutide 1.5 mg are included in the pack price; therefore, any costs related to needles are already accounted for. Costs for needles for liraglutide 1.2 mg are not included in the pack price, but for simplicity these were not included as an additional cost. Adherence to all modelled regimens was assumed to be 100%.

Table 2.

UK prices for once-weekly semaglutide, exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg

| Drug | Pack contents | Pack price (GBP) from MIMS [31] | Annual cost (GBP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semaglutide 1 mg | 4 mg | 0.5 mg, 4-dose pre-filled pen, 1 = GBP 73.25 | 956 |

| 1.0 mg, 4-dose pre-filled pen, 1 = GBP 73.25 | |||

| Exenatide ER 2 mg | 8 mg | 2.0 mg powder and solvent for sustained-release suspension for injection, pre-filled pen, 4 = GBP 73.36 | 957 |

| Dulaglutide 1.5 mg | 6 mg | 1.5 mg/0.5 ml pre-filled pen, 4 = GBP 73.25 | 956 |

| Liraglutide 1.2 mg | 36 mg | 3 ml pre-filled pens, 2 = GBP 78.48 | 955 |

ER extended-release, MIMS Monthly Index of Medical Specialities

Model and Relative Cost of Control Calculations

A model was developed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to assess the relative costs of a single patient achieving each pre-specified single or composite endpoint in the three trials. This model has been used previously to evaluate the relative cost of control of once-weekly semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1 mg from a US perspective [27].

Relative efficacy and costs were calculated by dividing the proportions of patients achieving each target and the medication acquisition costs for each comparator by the corresponding values for once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg from the relevant SUSTAIN trial. Efficacy outcomes from SUSTAIN 3, SUSTAIN 7 and SUSTAIN 10 were reported over 56 weeks, 40 weeks and 30 weeks of follow-up, respectively; however, a constant ratio of costs between the treatment arms over time was assumed to avoid disparities arising from these different trial durations.

The model results were presented in terms of relative cost of control outcomes only (i.e. cost relative to once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg and efficacy relative to once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg) using the same method as the cost of control analysis of once-weekly semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1 mg from a US perspective [27]. Results were plotted on a cost–efficacy plane where the relative efficacy was plotted on the abscissa and the relative cost was plotted on the ordinate. Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg was used as the reference and formed the identity line or line of equality (i.e. x = y). Comparators that fall above the line have a worse efficacy-to-cost ratio (incurring higher costs for the same efficacy or lower efficacy for the same cost), and those that fall below the line have a better efficacy-to-cost ratio (incurring lower costs for the same efficacy or higher efficacy for the same cost). The relationship between cost and efficacy was assumed to be linear.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Annual Costs

The annual cost per patient was similar for once-weekly semaglutide, exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg (GBP 956, 957, 956 and 955, respectively).

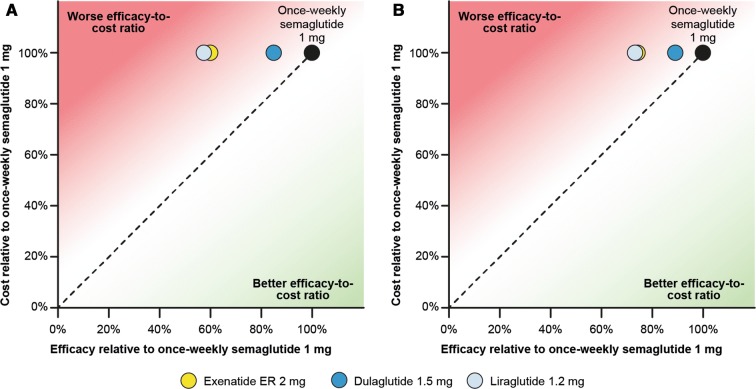

HbA1c

Compared with once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg, exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg were 40.3%, 15.2% and 42.9% less efficacious in helping patients to achieve HbA1c < 7.0%, respectively (Fig. 1a). A similar pattern was observed for target HbA1c < 7.5% (25.8%, 11.0% and 26.9%, respectively) (Fig. 1b). Because the cost of treatment was similar, the efficacy-to-cost ratios of bringing patients to HbA1c targets of < 7.0% and < 7.5% were better with once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg than with exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg. When a target of HbA1c ≤ 6.5% was evaluated, a similar trend was seen (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material).

Fig. 1.

Relative cost-to-efficacy ratio of bringing patients to a HbA1c target of a < 7.0% and b < 7.5%. ER extended-release

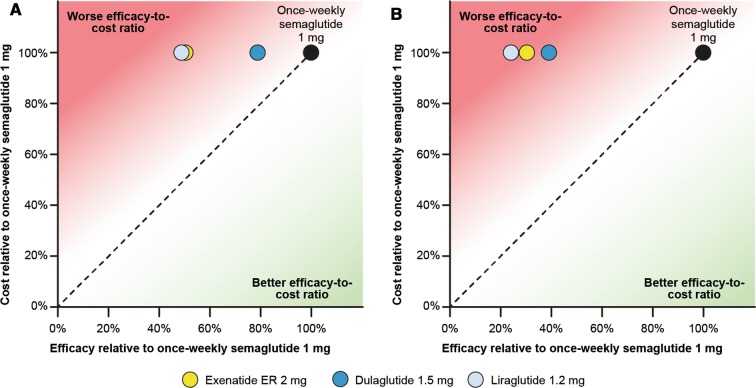

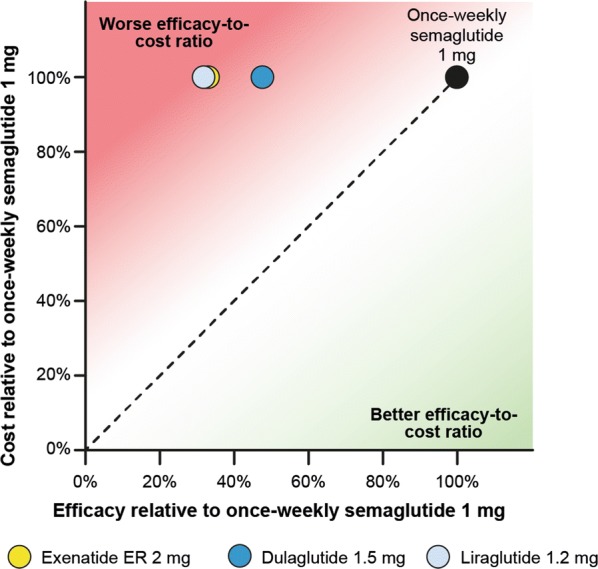

Weight Loss

Once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg was also strongly differentiated from the comparators in helping patients to achieve weight loss. Compared with once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg, exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg were 67.3%, 52.4% and 68.3% less efficacious, respectively, in helping patients to achieve a weight loss of ≥ 5% (Fig. 2). Therefore, the efficacy-to-cost ratio of helping patients to achieve a weight loss of ≥ 5% was better with once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg than with exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg. A similar trend was seen when evaluating a weight loss target of ≥ 10% (Fig. S2 in the supplementary material).

Fig. 2.

Relative cost-to-efficacy ratio of reducing patients’ weight by 5% or more. ER extended-release

Composite Endpoint of HbA1c, Weight Loss and Hypoglycaemia

The trends observed for single endpoints were reflected in the results for composite endpoints, with once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg showing similar or greater differentiation versus comparators. Exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg were 50.0%, 21.6% and 51.3% less efficacious than once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg, respectively, in helping patients to achieve the composite endpoint of HbA1c < 7.0% without weight gain or hypoglycaemia (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Relative cost-to-efficacy ratio of a bringing patients to a HbA1c target of < 7.0% without weight gain or hypoglycaemia or b reducing HbA1c by ≥ 1.0% and reducing weight by ≥ 5%. ER extended-release

Similarly, exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg were less efficacious than once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg (69.8%, 61.0% and 76.0%, respectively) in helping patients to achieve the composite endpoint of a reduction in HbA1c of ≥ 1.0% with a reduction in weight of ≥ 5% (Fig. 3b).

The efficacy-to-cost ratio of helping patients to achieve both of these composite endpoints was better with once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg than with exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg.

Discussion

The present study used data from SUSTAIN 3, SUSTAIN 7 and SUSTAIN 10 to assess the relative cost of control, defined as achieving various clinically relevant targets encompassing glycaemic control, weight gain and hypoglycaemia, for therapies used to treat people with T2D. From an NHS perspective, once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg offers a better cost-to-efficacy ratio than exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg for patients achieving these clinically relevant endpoints. Our results support those of previous cost of control analyses conducted in the USA and the UK, in which once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg was shown to provide better value for money than exenatide ER and dulaglutide in helping patients to reach a treatment target of HbA1c < 7% without weight gain or hypoglycaemia [27, 29]. Our chosen targets for HbA1c and weight loss are clinically relevant, associated with reduced risk of diabetes-related complications and in line with current NICE guidance [14] and our previous cost of control analyses [27]. Furthermore, this is the first cost of control analysis comparing once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg with liraglutide 1.2 mg.

Strengths

Short-term analyses, such as ours, have several advantages over long-term analyses. These analyses can be easily updated if new clinical data become available or if wholesale acquisition costs change. Our analysis is based on a previously developed model and assumptions, permitting easy adaptation to a different setting [27]. In addition, the analyses are easy to conduct and interpret, and provide a clear picture of relative cost-effectiveness for different treatments in terms of clinically relevant targets. Finally, no long-term projections of short-term data are required, avoiding the uncertainty associated with data extrapolation. Short-term cost-effectiveness analyses are intended to complement, rather than replace, long-term cost-effectiveness modelling, and can provide supportive evidence for the results of analyses that extrapolate over a longer time span. Our findings are similar to those of a previous long-term cost-effectiveness analysis of once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg versus dulaglutide 1.5 mg from a UK perspective, which found that once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg was associated with cost savings as well as improved outcomes [26].

Limitations

One limitation of our analysis is that it does not consider long-term complications or improvements in those patients who do not reach targets. Short-term reductions in HbA1c and body weight are associated with a reduced incidence of long-term diabetes-related complications [8–10, 16]; therefore, the short-term efficacy benefits seen in the present analysis are likely to be associated with further benefits over patients’ lifetimes. For this reason, the captured costs, time horizon and adopted budget perspective should all be considered when interpreting our cost of control analysis, and the results should be considered in the context of wider published cost-effectiveness evidence. In addition, adherence was assumed to be 100% for all treatments, which may not reflect clinical practice.

Another limitation of the current analysis is that only wholesale acquisition drug costs were used, with costs of blood glucose monitoring, interactions with healthcare professionals and adverse events (AEs) not being captured. Costs associated with blood glucose monitoring were assumed to be the same, regardless of treatment; however, wholesale acquisition costs include needles for once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg but not for liraglutide 1.2 mg. Consequently, the results of our analysis compared with liraglutide 1.2 mg are conservative because costs of needles would be greater for liraglutide 1.2 mg. AEs were not included in the present study because it focussed on endpoints pre-specified in the SUSTAIN trials, encompassing glycaemic control, weight gain and hypoglycaemia, and for parity with our previous cost of control analysis conducted in the USA [27]. The only endpoint included that was not pre-specified and was generated post hoc was the target HbA1c of < 7.5%; this endpoint was included because NICE recommends that patients intensify treatment when their HbA1c exceeds 7.5%, and this endpoint is therefore highly relevant for UK clinical practice [14]. The inclusion of additional endpoints, such as AEs, in a modified cost of control analysis could be of interest in future studies; however, because the safety profiles of once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg, exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg were very similar in the SUSTAIN trial programme, we expect that this would not strongly affect the findings.

Finally, the periods of follow-up differed between studies: SUSTAIN 3 reported the proportions of patients reaching targets after 56 weeks, whereas SUSTAIN 7 and SUSTAIN 10 reported the same proportions over 40 weeks and 30 weeks, respectively. To mitigate the effect of this, cost and efficacy ratios, rather than absolute differences, were used. However, the differing follow-up periods should be considered in the interpretation and potential extrapolation of the outcomes.

Conclusions

The present analysis expanded on the results of the SUSTAIN 3, SUSTAIN 7 and SUSTAIN 10 clinical trials, which showed that once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg was more efficacious than exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg for helping patients to achieve clinically relevant endpoints comprising glycaemic control, weight loss and hypoglycaemia. Our analysis demonstrated that these endpoints could also be achieved more cost-effectively with once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg than with these comparators. Therefore, from the perspective of the NHS in the UK, once-weekly semaglutide 1 mg represents good value for money in the treatment of T2D, compared with exenatide ER 2 mg, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study, the Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were funded by Novo Nordisk A/S. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

The authors are grateful to Malgorzata Cel and Yasmin Ghani at Novo Nordisk for review of and input to the manuscript, and to Helen Schofield and Caroline Freeman at Oxford PharmaGenesis for medical writing assistance (funded by Novo Nordisk A/S).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

Pierre Johansen is an employee and shareholder of Novo Nordisk A/S (ORCID 0000-0002-6287-7508). Anna Sandberg is an employee of Novo Nordisk A/S. Matthew Capehorn is a partner at Clifton Medical Centre; is a partner and Clinical Manager of the Rotherham Institute for Obesity (RIO), which has received or is receiving research funding from Novo Nordisk, BI/Lilly Alliance, Janssen, GSK, Novartis, Merck, Leo Pharma, Bayer, Abbot, Cambridge Weight Plan, Lighterlife and Syneos; is a Director of RIO Weight Management Limited; is a Medical Director at Lighterlife (paid position); is an unpaid board member of the Association of the Study for Obesity (ASO); has received honoraria for Advisory Board meetings for Novo Nordisk, BI/Lilly Alliance, Janssen and MSK; has received payments for speaker meetings from Novo Nordisk and BI/Lilly Alliance, Sanofi-Aventis and Abbot; and has received travel and/or accommodation expenses to attend educational meetings from Novo Nordisk, BI/Lilly and Lighterlife.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.11637510.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Foundation. IDF diabetes atlas, 8th edn. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, United Kingdom country report 2017 and 2045. 2017. https://reports.instantatlas.com/report/view/704ee0e6475b4af885051bcec15f0e2c/GBR. Accessed Oct 2019.

- 2.Diabetes UK. Us, diabetes and a lot of facts and stats. 2019. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/resources-s3/2019-02/1362B_Facts%20and%20stats%20Update%20Jan%202019_LOW%20RES_EXTERNAL.pdf. Accessed Oct 2019.

- 3.National Health Service. National diabetes audit, 2015–16. Report 2a: complications and mortality (complications of diabetes). 2017. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/pdf/4/t/national_diabetes_audit__2015-16__report_2a.pdf. Accessed Nov 2019.

- 4.International Diabetes Foundation. IDF diabetes atlas, 8th edn. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation. 2017. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/. Accessed Sep 2019.

- 5.Holman N, Young RJ, Jeffcoate WJ. Variation in the recorded incidence of amputation of the lower limb in England. Diabetologia. 2012;55(7):1919–1925. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2468-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arun CS, Ngugi N, Lovelock L, Taylor R. Effectiveness of screening in preventing blindness due to diabetic retinopathy. Diabet Med. 2003;20(3):186–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.t01-1-00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips A, Mehl AA. Diabetes mellitus and the increased risk of foot injuries. J Wound Care. 2015;24(5 Suppl 2):4–7. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2015.24.Sup5b.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–853. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Advance Collaborative Group. Patel A, MacMahon S, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2560–2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1577–1589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zoungas S, Patel A, Chalmers J, et al. Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(15):1410–1418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris SB, Khunti K, Landin-Olsson M, et al. Descriptions of health states associated with increasing severity and frequency of hypoglycemia: a patient-level perspective. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:925–936. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S46805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Currie CJ, Morgan CL, Poole CD, Sharplin P, Lammert M, McEwan P. Multivariate models of health-related utility and the fear of hypoglycaemia in people with diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(8):1523–1534. doi: 10.1185/030079906X115757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management [NG28]. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/chapter/1-Recommendations#blood-glucose-management-2. Accessed Sep 2019.

- 15.National Diabetes Audit, 2016–17. Care Processes and Treatment Targets short report. 2017. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publication/g/3/national_diabetes_audit_2016-17_short_report__care_processes_and_treatment_targets.pdf. Accessed Sep 2019.

- 16.Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1481–1486. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung RT. Obesity as a disease. Br Med Bull. 1997;53(2):307–321. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Diabetes Association 6. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Supplement 1):S61–S70. doi: 10.2337/dc19-S006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran KL, Park YI, Pandya S, et al. Overview of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2017;10(4):178–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmann AJ, Capehorn M, Charpentier G, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus exenatide ER in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 3): a 56-week, open-label, randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(2):258–266. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pratley RE, Aroda VR, Lingvay I, et al. Semaglutide versus dulaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 7): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(4):275–286. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capehorn MS, Catarig AM, Furberg JK, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide 1.0 mg vs once-daily liraglutide 1.2 mg as add-on to 1–3 oral antidiabetic drugs in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 10). Diabetes Metab. 2019. 10.1016/j.diabet.2019.101117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.European Medicines Agency. EPAR summary for the public. Ozempic. 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/ozempic. Accessed Nov 2019.

- 24.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE technology appraisal guidance. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-technology-appraisal-guidance. Accessed Oct 2019.

- 25.TheKingsFund. The NHS budget and how it has changed. 2019. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/nhs-in-a-nutshell/nhs-budget. Accessed Oct 2019.

- 26.Viljoen A, Hoxer CS, Johansen P, Malkin S, Hunt B, Bain SC. Evaluation of the long-term cost-effectiveness of once-weekly semaglutide versus dulaglutide for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the UK. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(3):611–621. doi: 10.1111/dom.13564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johansen P, Hunt B, Iyer NN, Dang-Tan T, Pollock RF. A relative cost of control analysis of once-weekly semaglutide versus exenatide extended-release and dulaglutide for bringing patients to HbA1c and weight loss treatment targets in the USA. Adv Ther. 2019;36(5):1190–1199. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-00915-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu AR, Bech PG, Leiter LA, Moreno SI, Håkan-Bloch J, Johansen P. Once-weekly semaglutide provides better value for money than a broad range of other type 2 diabetes treatments in Canada: a relative cost of control analysis. Can J Diabetes. 2018;42(5):S41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2018.08.125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollock RF, Hallén N, Hoxer CS. The value of once weekly semaglutide in bringing people with type 2 diabetes to single and composite endpoints: a UK cost of control analysis vs dulaglutide, exenatide extended-release, sitagliptin and insulin glargine U100. Diabet Med. 2019;36(S1):170. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodbard HW, Bellary S, Hramiak I, et al. Greater combined reductions in HbA1c ≥ 1.0% and weight ≥ 5.0% with semaglutide versus comparators in type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2019;25(6):589–597. doi: 10.4158/EP-2018-0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monthly Index of Medical Specialities. 2019. https://www.mims.co.uk/. Accessed Sep 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.