Abstract

Introduction

Endometriosis symptoms are nonspecific and overlap with other gynecologic and gastrointestinal diseases, leading to long diagnostic delays. The burden of endometriosis has been documented; however, little is known about the impact of diagnostic delays on healthcare costs leading up to diagnoses. The purpose of this study was to examine the economic impact of diagnostic delays on pre-diagnosis healthcare utilization and costs among patients with endometriosis.

Methods

This was a retrospective database study of adult patients with a diagnosis of endometriosis from 1 January 2004 to 31 July 2016. Patients had continuous health plan enrollment 60 months prior to and 12 months following the earliest endometriosis diagnosis and ≥ 1 pre-diagnosis endometriosis symptom (dyspareunia, generalized pelvic pain, abdominal pain, dysmenorrhea, or infertility). Patients were assigned to short (≤ 1 year), intermediate (1–3 years), or long (3–5 years) delay cohorts based on the length of their diagnostic delay (time from first symptom to diagnosis). Healthcare resource utilization and costs were calculated and compared by cohort in the 60-month pre-diagnosis period.

Results

A total of 11,793 patients were included in the study, of which 37.7% (4446/11,793), 27.0% (3179/11,793), and 35.3% (4168/11,793) had short, intermediate, and long delays, respectively. Patients with intermediate or long diagnostic delays had consistently more all-cause and endometriosis-related emergency visits and inpatient hospitalizations in the pre-diagnosis period than patients with short delays. Pre-diagnosis all-cause healthcare costs were significantly higher among patients with longer diagnostic delays, averaging $21,489, $30,030, and $34,460 among patients with a short, intermediate, and long delay, respectively (p < 0.001 for all pairwise comparisons). Endometriosis-related costs accounted for 12.5% ($3553/$28,376) of all-cause costs and followed a similar pattern.

Conclusion

Patients with endometriosis who had longer diagnostic delays had more pre-diagnosis endometriosis-related symptoms and higher pre-diagnosis healthcare utilization and costs compared with patients who were diagnosed earlier after symptom onset, providing evidence in support of earlier diagnosis.

Keywords: Diagnostic delay, Endometriosis, Healthcare costs, Healthcare utilization, Women’s health

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Due to non-specific symptoms that overlap with other gynecologic, urologic, and gastrointestinal issues, long diagnostic delays are prevalent among patients with endometriosis |

| Little information is known about the impact diagnostic delays may have on healthcare costs leading up to diagnosis |

| The purpose of this study was to examine the economic impact of diagnostic delays on pre-diagnosis healthcare utilization and costs among patients with endometriosis |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Pre-diagnosis all-cause and endometriosis-related healthcare costs were higher among patients with longer diagnostic delays |

| Patients with intermediate or long diagnostic delays had consistently more all-cause and endometriosis symptom-related emergency visits and inpatient hospitalizations in the pre-diagnosis period than patients with short delays |

Introduction

Endometriosis affects approximately 10% of reproductive-aged women [1–3] with symptoms of abdominal or pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, menstrual abnormalities, constipation, dyschezia, dysuria, urinary frequency and urgency, and dyspareunia [4–6]. Chronic pain and infertility due to endometriosis have been shown to significantly decrease quality of life and increase physical and psychologic morbidity [6–10]. Endometriosis has also been associated with a twofold or higher increased risk of developing comorbidities including ovarian cysts, uterine fibroids, pelvic inflammatory disorder, interstitial cystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, and ovarian and endometrial cancers [11].

Endometriosis diagnosis often presents challenges as symptoms are nonspecific and overlap with other gynecologic, urologic, and gastrointestinal issues resulting in long diagnostic delays. Nnoaham et al. documented an average diagnostic delay of 6.7 years among patients with endometriosis mainly due to delays in referral from primary care to a specialist [12]. Soliman et al. reported an average diagnostic delay of 4.4 years with 89% of diagnoses made by obstetricians/gynecologists [13]. Several reasons for endometriosis diagnostic delays have been identified including both patient-centered causes such as embarrassment, stigmatization, tolerance, or uncertainty of normal versus abnormal symptoms and physician-centered causes such as normalization of patient symptoms and reliance on inadequate diagnostic methods [14]. Clinical guidelines do not provide a consistent approach to the diagnosis and management of endometriosis with little attention given to the presence of comorbidities, which may contribute to diagnostic delays [15, 16].

Patients with endometriosis experience significant healthcare expenses. In a study of endometriosis patients and matched controls, mean annual adjusted direct healthcare costs were more than three times higher in endometriosis patients than controls during the 12 months following diagnosis ($16,573 versus $4733, p < 0.005) [17]. Fuldeore et al. found that costs were highest in the first year following an endometriosis diagnosis, costing $13,199 compared with $6041 in the year prior to diagnosis and $6720 in the year following the index year. Additionally, in the 5 years prior to an endometriosis diagnosis, costs were $7028 higher among patients with endometriosis compared with matched controls without endometriosis [18].

The economic burden of endometriosis has been well documented in the literature; however, little is known about the impact a diagnostic delay may have on healthcare costs leading up to diagnosis. This study focused on the time period prior to diagnosis to attempt to address this gap. The purpose of this study was to examine the economic impact of diagnostic delays on pre-diagnosis healthcare utilization and costs among patients with endometriosis.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

This retrospective study used the Optum Research Database, a geographically diverse US database representing approximately 67 million individuals from 1993 to present. Medical and pharmacy claims and enrollment information were obtained from 1 January 1999 to 31 July 2017 (study period). Medical claims consisted of International Classification of Disease, Ninth and Tenth Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) diagnosis and procedure codes, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes, and revenue codes. Pharmacy claims included National Drug Codes for filled prescriptions and days and quantity of drug supplied. The Optum Research Database is fully de-identified and HIPAA compliant and did not require Institutional Review Board approval or waiver of authorization.

Study Population

Patients were required to be aged 18–49 years and have ≥ 1 medical claim for endometriosis in any position (ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM diagnosis code 617.x/N80.x) from 1 January 2004 to 31 July 2016 (identification period). The date of the first medical claim with an endometriosis diagnosis code was considered the index date. Patients were required to have continuous health plan enrollment with medical and pharmacy benefits for ≥ 60 months (1825 days) prior to the index date (pre-diagnosis period) and ≥ 12 months (365 days) following the index date and a medical claim for ≥ 1 endometriosis symptom in any position (dyspareunia, generalized pelvic pain, abdominal pain, dysmenorrhea, or infertility) during the pre-diagnosis period. A pre-diagnosis period of 5 years was selected based on recent evidence from Soliman et al. who reported the average delay from first symptom to endometriosis diagnosis was approximately 4.4 years [13]. Endometriosis symptoms were selected based on published literature [4, 5] and guidance from the clinician author. Patients with a medical claim for endometriosis or malignancy prior to the index date were excluded from the study. To rule out patients with conditions that have symptoms similar to endometriosis, patients with an ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnosis code for genitourinary or intra-abdominal infection (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea), inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, appendicitis, peritonitis, other genitourinary conditions (cystitis, urethritis), or kidney stones any time prior to the index date were also excluded.

Patients were assigned to delay cohorts based on the length of time from the date of the first medical claim for a non-diagnostic service for an endometriosis symptom to the index date categorized as: short delay (≤ 1 year), intermediate delay (1–3 years), and long delay (3–5 years). These cutoffs are conservative estimates of disease burden and were chosen to balance the clinical burden and sample size requirements for the study.

Study Measures

Patient Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics that included patient age, geographic region, insurance type (commercial or Medicare Advantage), length of diagnostic delay, disease severity (proxy based on the annualized count of endometriosis symptoms), and targeted endometriosis-related comorbid conditions were measured using claims data during the pre-diagnosis period.

Pre-Diagnosis Healthcare Resource Utilization

All-cause and endometriosis-related healthcare resource utilization was calculated as the mean number of ambulatory (office and outpatient) visits, emergency visits, and inpatient stays during the 60-month pre-diagnosis period. Utilization was considered endometriosis-related if the medical claim included a diagnosis code for an endometriosis symptom (dyspareunia, generalized pelvic pain, abdominal pain, dysmenorrhea, or infertility), a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) or HCPCS code for an endometriosis treatment procedure (e.g., laparoscopy), or a HCPCS code for an endometriosis-related medication administration (e.g., neuropathic pain agent, progestin, hormonal contraceptive, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) in a physician’s office.

Pre-Diagnosis Healthcare Costs

All-cause and endometriosis-related healthcare costs were calculated as the combined health plan and patient-paid amounts during the 60-month pre-diagnosis period adjusted for inflation from 1999 to 2016 using the annual medical care component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) [19]. Costs were considered endometriosis-related if the medical claim included a diagnosis for an endometriosis symptom, a CPT or HCPCS code for an endometriosis treatment, or a pharmacy claim for a medication used to treat endometriosis or its symptoms (e.g., neuropathic pain agent, progestin, hormonal contraceptive, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). The diagnosis code on the medical claim for the endometriosis symptom must have been in the primary position to be considered endometriosis-related emergency or inpatient costs.

Statistical Analyses

All study variables were analyzed descriptively, and comparisons between delay cohorts were made. Mean healthcare utilization and costs over the 60-month pre-diagnosis period were calculated and presented separately for each of the three diagnostic delay cohorts. Statistical tests of significance for differences across the three cohorts were conducted using chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA and t test for continuous variables. For endometriosis-specific healthcare resource utilization and costs, the hypothesis tested was whether patients who have had endometriosis symptoms for a longer period of time would have mean utilization and costs equal to patients who have had endometriosis symptoms for a shorter period of time. Calculated p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction) with a threshold of statistical significance of p < 0.017.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

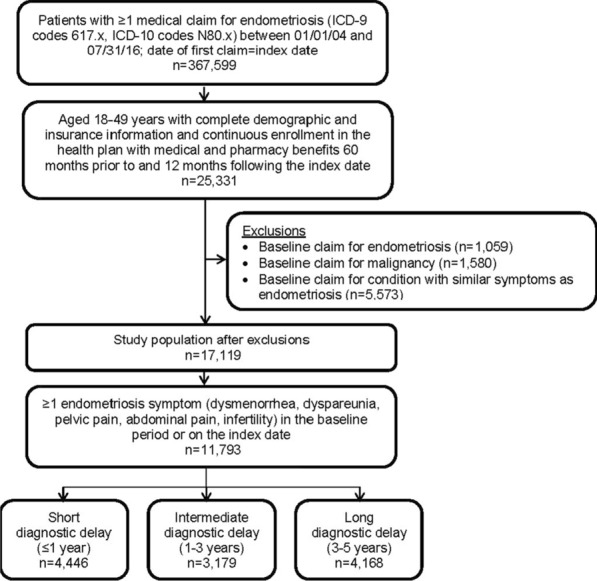

After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 11,793 patients were included in the study, of which 37.7% (n = 4446) had a short delay, 27.0% (n = 3179) had an intermediate delay, and 35.3% (n = 4168) had a long delay (Fig. 1). Patients with a short delay were slightly older (39.8 ± 7.0) than patients who had intermediate (38.9 ± 7.8) or long delays (38.9 ± 7.6) (p < 0.001 for both comparisons) (Table 1). Approximately half of all patients resided in the South, and 66% had a point of service healthcare plan (p value not significant).

Fig. 1.

Patient sample selection

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics during the 60-month pre-diagnosis period

| Total (n = 11,793) | Short delay (n = 4446) | Intermediate delay (n = 3179) | Long delay (n = 4168) | Short versus intermediate p value |

Short versus long p value |

Intermediate versus long p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 39.3 (7.4) | 39.8 (7.0) | 38.9 (7.8) | 38.9 (7.6) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.940 |

| Region, n (%) | 0.747 | 0.025 | 0.188 | ||||

| Northeast | 850 (7.2) | 291 (6.6) | 218 (6.9) | 341 (8.2) | |||

| Midwest | 3301 (28.0) | 1263 (28.4) | 885 (27.8) | 1153 (27.7) | |||

| South | 5892 (50.0) | 2246 (50.5) | 1591 (50.1) | 2055 (49.3) | |||

| West | 1748 (14.8) | 646 (14.5) | 485 (15.3) | 617 (14.8) | |||

| Other | 2 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | |||

| Length of diagnostic delay (days), mean (SD) | 763.9 (631.0) | 90.2 (103.6) | 733.4 (213.7) | 1505.9 (212.0) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Presence of endometriosis symptoms, n (%) | |||||||

| Dysmenorrhea | 6132 (52.0) | 2420 (54.4) | 1578 (49.6) | 2134 (51.2) | < 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.185 |

| Dyspareunia | 1536 (13.0) | 562 (12.6) | 413 (13.0) | 561 (13.5) | 0.651 | 0.259 | 0.558 |

| Pelvic pain | 346 (2.9) | 145 (3.3) | 81 (2.6) | 120 (2.9) | 0.070 | 0.305 | 0.389 |

| Abdominal pain | 7935 (67.3) | 2156 (48.5) | 2354 (74.1) | 3425 (82.2) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Infertility | 1414 (12.0) | 374 (8.4) | 421 (13.2) | 619 (14.9) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.050 |

| Count of endometriosis symptoms,a mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Symptom severity proxy (annualized count), mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Most common endometriosis-related comorbidities, n (%) | |||||||

| Fatigue neurasthenia | 5804 (49.2) | 1912 (43.0) | 1617 (50.9) | 2275 (54.6) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Headache and migraine | 5046 (42.8) | 1566 (35.2) | 1417 (44.6) | 2063 (49.5) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Ovarian cysts | 4790 (40.6) | 1604 (36.1) | 1314 (41.3) | 1872 (44.9) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Urinary tract infection | 4570 (38.8) | 1374 (30.9) | 1350 (42.5) | 1846 (44.3) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.118 |

| Depression and anxiety | 4437 (37.6) | 1428 (32.1) | 1223 (38.5) | 1786 (42.9) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Uterine fibroids | 4034 (34.2) | 1515 (34.1) | 1089 (34.3) | 1430 (34.2) | 0.870 | 0.819 | 0.962 |

| Count of comorbid conditions, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 491 (4.2) | 289 (6.5) | 97 (3.1) | 105 (2.5) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.167 |

| 1 | 1467 (12.4) | 766 (17.2) | 343 (10.8) | 358 (8.6) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| 2+ | 9835 (83.4) | 3391 (76.3) | 2739 (86.2) | 3705 (88.9) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

SD standard deviation

aEndometriosis symptoms included dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, abdominal pain, and infertility

Patients in this study had a mean diagnostic delay of 763.9 ± 631.0 days (2.09 ± 1.77 years) (Table 1). Patients with a short, intermediate, or long delay averaged 90.2 days, 733.4 days, and 1505.9 days, respectively, from the onset of endometriosis symptoms until diagnosis. Common symptoms identified were abdominal pain (67.3%), dysmenorrhea (52.0%), and dyspareunia (13.0%) (Table 1). Patients with a short delay were least likely to have abdominal pain and infertility, but were most likely to have dysmenorrhea compared with patients who had intermediate and long delays. The proportion of patients with abdominal pain increased significantly with increasing diagnostic delay (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Using the proxy for disease severity, patients with a long delay had a less concentrated presence of endometriosis symptoms than those with shorter delays ranging from a symptom severity of 0.3–1.0 (p < 0.001 for all comparisons; Table 1).

Almost all patients (95.8%) had ≥ 1 comorbid condition (Table 1), with the most common being fatigue/neurasthenia (49.2%), headache and migraine (42.8%), ovarian cysts (40.6%), urinary tract infections (38.8%), depression and anxiety (37.6%), and uterine fibroids (34.2%). Comorbidities tended to be the highest among patients with longer delays.

Pre-Diagnosis Healthcare Utilization

All-Cause Utilization

Almost all patients had ≥ 1 all-cause ambulatory visit during the pre-diagnosis period (Table 2). The mean number of ambulatory visits increased with longer diagnostic delays from 47.3 visits among patients with a short delay, 61.0 visits in patients with an intermediate delay, to 69.1 visits among patients with a long delay (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Almost 66% of patients had an emergency room visit, and there was an average of 4.2 visits over the 60-month pre-diagnosis period. The proportion of patients with an emergency room visit increased significantly with longer diagnostic delays ranging from 58.0% in those with a short delay, 69.0% in those with an intermediate delay, and 71.9% in patients with a long delay (p ≤ 0.007 for all comparisons). The mean number of emergency room visits was significantly lower in patients with a short delay compared with patients with an intermediate or long delay (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). Approximately 22% of patients had an inpatient stay during the pre-diagnosis period. Both the proportion of patients with an inpatient stay and the mean number of stays during the pre-diagnosis period increased as the length of diagnostic delay increased (p < 0.001 for all comparisons).

Table 2.

Healthcare resource utilization during the 60-month pre-diagnosis period

| Total (n = 11,793) | Short delay (n = 4446) | Intermediate delay (n = 3179) | Long delay (n = 4168) | Short versus intermediate p value |

Short versus long p value |

Intermediate versus long p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cause | |||||||

| Ambulatory visit count, mean (SD) | 58.7 (44.6) | 47.3 (35.9) | 61.0 (45.3) | 69.1 (49.4) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Proportion with ≥ 1 visit, n (%) | 11,790 (100.0) | 4443 (99.9) | 3179 (100.0) | 4168 (100.0) | 0.143 | 0.093 | – |

| Emergency visit count, mean (SD) | 4.2 (12.0) | 3.3 (9.7) | 4.6 (12.2) | 5.0 (13.9) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.177 |

| Proportion with ≥ 1 visit, n (%) | 7769 (65.9) | 2580 (58.0) | 2193 (69.0) | 2996 (71.9) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.007 |

| Inpatient stay count, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.9) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Proportion with ≥ 1 stay, n (%) | 2541 (21.6) | 763 (17.2) | 685 (21.6) | 1093 (26.2) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Endometriosis related | |||||||

| Ambulatory visit count, mean (SD) | 4.6 (5.8) | 2.4 (2.9) | 5.0 (5.5) | 6.6 (7.4) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Proportion with ≥ 1 visit, n (%) | 10,829 (91.8) | 3599 (81.0) | 3130 (98.5) | 4100 (98.4) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.760 |

| Emergency visit count, mean (SD)a | 0.2 (0.8) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.9) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Proportion with ≥ 1 visit, n (%)a | 1985 (16.8) | 422 (9.5) | 594 (18.7) | 969 (23.3) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Inpatient stay count, mean (SD)a | 0.03 (0.2) | 0.02 (0.2) | 0.03 (0.2) | 0.05 (0.3) | 0.007 | < 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Proportion with ≥ 1 stay, n (%)a | 353 (3.0) | 85 (1.9) | 90 (2.8) | 178 (4.3) | 0.008 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

SD standard deviation

aDiagnosis code for the endometriosis symptom had to in the primary position on the claim

Endometriosis-Related Utilization

Approximately 92% of patients had an endometriosis-related ambulatory visit during the pre-diagnosis period (Table 2). The number of ambulatory visits increased with longer diagnostic delays ranging from 2.4 visits among short delay patients, 5.0 visits among intermediate delay patients, and 6.6 visits among long delay patients (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Overall, one in six patients had an endometriosis-related emergency visit during the pre-diagnosis period. Patients with longer delays were more likely to have an endometriosis-related emergency room visit (p < 0.001 for all comparisons) and a greater number of endometriosis-related emergency visits (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Endometriosis-related inpatient stays were rare and increased with longer diagnostic delays (p ≤ 0.007 for all comparisons).

Pre-Diagnosis Healthcare Costs

All-Cause Costs

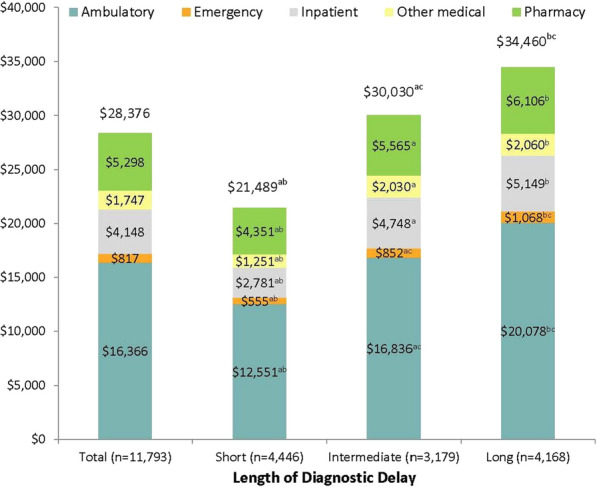

All-cause healthcare costs during the pre-diagnosis period averaged $28,376 (Fig. 2). Ambulatory costs were the major cost driver accounting for 57.7% of total all-cause costs. All-cause costs were significantly higher in patients with longer diagnostic delays. Mean total costs in patients with a long delay were 60.4% and 14.8% higher than costs in patients with a short and intermediate delay, respectively (p < 0.001 for all comparisons). All-cause pharmacy costs in patients with a short delay ($4351) were significantly lower than costs in patients with an intermediate ($5565) or long delay ($6106) (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). All-cause medical costs were also significantly higher with longer diagnostic delays ($17,138, $24,465, and $28,354 in patients with a short, intermediate, and long delay, respectively) (p < 0.001 for all comparisons).

Fig. 2.

All-cause healthcare costs over the 60-month pre-diagnosis period. ap < 0.017 in comparison of the short and intermediate delay cohorts. bp < 0.017 in comparison of short and long delay cohorts. cp < 0.017 in comparison of intermediate and long delay cohorts

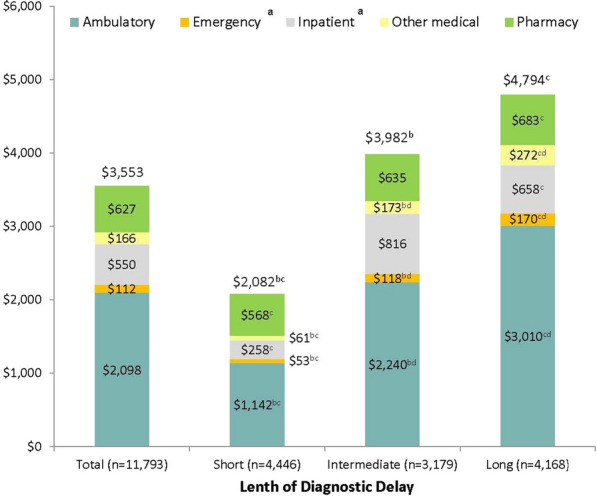

Endometriosis-Related Costs

Pre-diagnosis endometriosis-related healthcare costs accounted for 12.5% of all-cause costs. This proportion was highest among patients with longer diagnostic delays with values of 9.7%, 13.3%, and 13.9% in patients with short, intermediate, and long delays, respectively. The major cost driver was ambulatory visits accounting for 59.1% of total endometriosis-related costs (Fig. 3). Compared with patients with a short delay, pre-diagnosis endometriosis-related costs were almost double and more than double those in patients with intermediate or long delays, respectively (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). Endometriosis-related pharmacy costs were also highest among patients with a long delay and lowest among those with a short delay ($683 versus $568, p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Endometriosis-related healthcare costs over the 60-month pre-diagnosis period. aDiagnosis code for the endometriosis symptom had to in the primary position on the claim to be considered endometriosis-related. bp < 0.017 in comparison of short and intermediate delay cohorts. cp < 0.017 in comparison of short and long delay cohorts. dp < 0.017 in comparison of intermediate and long delay cohorts

Discussion

Diagnostic delays among patients with endometriosis have been well documented, but little information is known about the economic impact these delays have on the patient and healthcare system. This study identified patients with endometriosis stratified into cohorts defined by the length of time from the first claim for an endometriosis symptom to an endometriosis diagnosis. Patients with longer diagnostic delays had a significantly higher clinical burden with more endometriosis-related symptoms and comorbidities and a greater economic burden due to significantly higher healthcare resource utilization and costs compared with patients with shorter delays.

All-cause and endometriosis-related healthcare resource utilization increased with longer diagnostic delays. Patients had an average of 11.7 all-cause annualized ambulatory visits, 0.8 all-cause annualized emergency visits, and 0.1 all-cause annualized inpatient stay during the 60-month pre-diagnosis period. Similarly, Soliman et al. [17] reported that patients with endometriosis averaged 9.9 office/obstetrics-gynecology visits, 0.6 emergency visits, and 0.1 inpatient admissions in the 12 months prior to diagnosis. Utilization of healthcare services was also comparable to results described by Fuldeore et al. [18] who found emergency visits, outpatient visits, and physician visits increased over a 5-year period prior to endometriosis diagnosis peaking in the year immediately prior to diagnosis. In our study, patients with the longest diagnostic delay had 38% more all-cause ambulatory visits, 52% more all-cause emergency visits, and 100% more all-cause inpatient stays during the 60-month pre-diagnosis period compared with patients who had the shortest diagnostic delay. Future studies are needed to assess the economic impact of diagnostic delays post-endometriosis diagnosis.

All-cause and endometriosis-related healthcare costs increased with longer diagnostic delays. Patients with long diagnostic delays had 60% higher mean all-cause costs compared with patients with a short delay and 15% higher costs compared with patients with an intermediate delay. Mean annual costs in the 5 years prior to diagnosis ranged from $4298 in patients with a short delay to $6892 in patients with a long delay. These costs were similar to costs presented by Fuldeore et al., which ranged from $3730 (adjusted to 2016 USD) in the 5th year prior to endometriosis diagnoses to $6649 (adjusted to 2016 USD) in the year immediately prior to diagnoses [18]. It is possible that the higher costs seen in patients with a long diagnostic delay in this study could be a result of the greater number of endometriosis-related comorbidities found in those patients.

Endometriosis-related costs accounted for approximately 12.5% of total all-cause costs in the pre-diagnosis period. Ambulatory costs accounted for more than half of total endometriosis-related costs. Similar to all-cause costs, patients with the longest diagnostic delays experienced 130% higher endometriosis-related costs compared with patients with the shortest delays.

Patients with long diagnostic delays had more claims for endometriosis symptoms and endometriosis-related comorbidities over the 60-month pre-diagnosis period. The increased presence of comorbidities with similar symptomology to endometriosis may have further complicated the diagnosis of endometriosis leading to a longer diagnostic delay. Patients with a long delay also had significantly more endometriosis symptoms over the pre-diagnosis period, most notably abdominal pain and infertility. Nnoaham et al. [12] found that diagnostic delays were significantly longer in patients with more pelvic symptoms, which was consistent with results observed in our study. While patients with long delays experienced more symptoms and comorbidities over the 5-year pre-diagnosis period, patients with a short delay had more concentrated endometriosis symptoms in the year they experienced symptoms, which may have facilitated an earlier diagnosis.

The results of this study highlight the significant pre-diagnostic clinical and economic impact of diagnostic delays on patients with endometriosis. Several approaches have been investigated to shorten the diagnostic delay, including earlier detection of endometriosis symptoms through increased physician awareness and training, use of non-surgical methods of diagnosis (i.e., transvaginal ultrasound), and early treatment interventions based on symptoms, signs, and clinical findings prior to confirmation with laparoscopy [6, 13, 20–22]. Due to the hidden economic burden associated with the delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis and the important implications it has for healthcare decision makers, physicians, and payers, future research is needed in this area to determine if earlier detection of endometriosis using the above approaches can reduce this burden.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Healthcare claims are collected for the purpose of payment, not research, which leads to several inherent limitations. The presence of an endometriosis diagnosis code on a medical claim is not proof of the presence of disease. The diagnosis code may be incorrectly coded or included as rule-out criteria rather than actual disease. It is possible that patients may have had a diagnosis of endometriosis prior to the baseline period, which may explain the older age of onset found in this study. The baseline period was extended to 5 years to minimize this risk. Additionally, endometriosis symptoms may not have been fully captured in the claims database. Endometriosis-related healthcare utilization and costs in the pre-diagnosis period were based on the presence of claims for five common endometriosis symptoms and endometriosis-related surgical and pharmacologic treatment. While this was done to provide conservative estimates, it is possible that the true costs and utilization due to endometriosis were higher in this population. This study included a managed care population and may not be generalizable to other populations. Additionally, due to the coverage of the health plan underlying the claims database, about half of the study patients were from the South. Since racial and ethnic data were not collected, we cannot know if this may have skewed study results. Lastly, due to the observational nature of this study and the descriptive analyses performed, it is possible that confounding factors not accounted for could contribute to the difference in costs and utilization between the diagnostic delay cohorts.

Conclusions

Patients with endometriosis with longer diagnostic delays had more pre-diagnosis endometriosis-related symptoms and comorbidities and higher pre-diagnosis healthcare resource utilization and costs compared with patients who were diagnosed sooner after symptom onset. Future research is needed to differentiate costs related to comorbidities associated with endometriosis versus those related to disease management and how therapeutic interventions directed specifically at disease management and early diagnosis can impact these costs. Further future research is needed to determine the impact of diagnostic delays in patients with endometriosis on quality of life, productivity losses, and relationships.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees were funded by AbbVie Inc. AbbVie participated in the study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; and review and approval of the final manuscript for publication. All authors had full access to all of the study results and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the results and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Deja Scott-Shemon, MPH, an employee of Optum. This assistance was funded by AbbVie Inc. Authors would also like to acknowledge Carolyn Martin for her assistance with analytic interpretation and manuscript review and Susan Peckous for her assistance with project management and dissemination of study results.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Eric Surrey has served as a consultant for AbbVie, has been a member of the AbbVie Inc. and Ferring speakers bureau, and serves on an advisory board for DOT Laboratories. Ahmed M. Soliman is an employee of and owns stock in AbbVie Inc. Cori Blauer-Peterson and Ashley Sluis are employees of Optum and were funded by AbbVie Inc. to conduct the study. Helen Trenz was an employee of Optum at the time this study was conducted and is currently employed by UnitedHealth Group.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The Optum Research Database is fully de-identified and HIPAA compliant and did not require Institutional Review Board approval or waiver of authorization.

Data Availability

The data contained in our database contain proprietary elements owned by Optum and therefore cannot be broadly disclosed or made publicly available at this time. The disclosure of these data to third party clients assumes certain data security and privacy protocols are in place and that the third party client has executed our standard license agreement which includes restrictive covenants governing the use of the data.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to: 10.6084/m9.figshare.11417625.

References

- 1.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eskenazi B, Warner ML. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24:235–258. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8545(05)70302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cramer DW, Missmer SA. The epidemiology of endometriosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;955:11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuldeore MJ, Soliman AM. Prevalence and symptomatic burden of diagnosed endometriosis in the United States: National estimates from a cross-sectional survey of 59,411 women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2017;82:453–461. doi: 10.1159/000452660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Graaff AA, D’Hooghe TM, Dunselman GA, et al. The significant effect of endometriosis on physical, mental and social wellbeing: results from an international cross-sectional survey. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2677–2685. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angalakuditi M, Edgell E, Beardsworth A, Buysman E, Bancroft T. Treatment patterns and resource utilization and costs among patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension in the United States. J Med Econ. 2010;13:393–402. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.496694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:400–412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soliman AM, Coyne KS, Gries KS, Castelli-Haley J, Snabes MC, Surrey ES. The effect of endometriosis symptoms on absenteeism and presenteeism in the workplace and at home. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:745–754. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.7.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soliman AM, Coyne KS, Zaiser E, Castelli-Haley J, Fuldeore MJ. The burden of endometriosis symptoms on health-related quality of life in women in the United States: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38:238–248. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2017.1289512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winkel CA. Evaluation and management of women with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00474-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surrey ES, Soliman AM, Johnson SJ, Davis M, Castelli-Haley J, Snabes MC. Risk of developing comorbidities among women with endometriosis: a retrospective matched cohort study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:1114–1123. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(366–73):e8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soliman AM, Fuldeore M, Snabes MC. Factors associated with time to endometriosis diagnosis in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26:788–797. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What’s the delay? A qualitative study of women’s experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1296–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ay W. The significance of diagnostic delay in endometriosis. MOJ Womens Health. 2016;2:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seear K. The etiquette of endometriosis: stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1220–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soliman AM, Surrey E, Bonafede M, Nelson JK, Castelli-Haley J. Real-world evaluation of direct and indirect economic burden among endometriosis patients in the United States. Adv Ther. 2018;35:408–423. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0667-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuldeore M, Yang H, Du EX, Soliman AM, Wu EQ, Winkel C. Healthcare utilization and costs in women diagnosed with endometriosis before and after diagnosis: a longitudinal analysis of claims databases. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clinical Classification Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Comorbidities defined by Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) comorbidity software. 2015. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp. Accessed 1 Aug 2019.

- 20.Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, et al. Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:354.e1–354.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Kennedy SH, Jenkinson C, Zondervan KT, World Endometriosis Research Foundation Women’s Health Symptom Survey C Developing symptom-based predictive models of endometriosis as a clinical screening tool: results from a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:692–701. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009591.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data contained in our database contain proprietary elements owned by Optum and therefore cannot be broadly disclosed or made publicly available at this time. The disclosure of these data to third party clients assumes certain data security and privacy protocols are in place and that the third party client has executed our standard license agreement which includes restrictive covenants governing the use of the data.