Abstract

The cellular machinery regulating microRNA biogenesis and maturation relies on a small number of simple steps and minimal biological requirements, and is broadly conserved in all eukaryotic cells. The same holds true in disease. This allows for a significant degree of freedom in the engineering of transgenes capable of simultaneously expressing multiple microRNAs of choice, allowing a more comprehensive modulation of microRNA landscapes, the study of their functional interaction, and the possibility to use such synergism for gene therapy applications. We have previously engineered a transgenic cluster of functionally associated microRNAs to express a module of suppressed microRNAs in brain cancer for therapeutic purposes. Here we provide a detailed protocol for the design, cloning, delivery and utilization of such artificial microRNA clusters for gene therapy purposes. In comparison to other protocols, our strategy significantly decreases the requirements for molecular cloning, as the nucleic acid sequence encoding the combination of desired microRNAs is designed and validated in silico, and then directly synthesized as DNA which is ready for subcloning into appropriate delivery vectors, for both in vitro and in vivo use. Sequence design and engineering requires 4-5 hours. Synthesis of the resulting DNA sequence requires 4-6 hours. This protocol is quick, flexible, and does not require special laboratory equipment or techniques, nor multiple cloning steps. It can be easily executed by any graduate students or technicians with basics molecular biology knowledge.

Keywords: microRNA, clusters, DNA editing, gene therapy, multitargeting, cancer

Introduction

In the era of deep sequencing and comprehensive gene expression analysis, it has become evident that many diseases, ranging from neurodegeneration1–3 to cancer4,5, result from the simultaneous deregulation of multiple genes. Gene therapy holds great potential for treating these conditions, as long as strategies to tackle this multifactorial nature are implemented. MicroRNAs are well suited to fulfill this requirement. This is due to 1) their small size (~20 nucleotides in their active form)6; 2) their simple biogenesis7; 3) their ability to regulate multiple targets at once8, and 4) their natural tendency to function in clusters, demonstrated by the existence of several polycistronic loci within the genome which encode multiple microRNA sequences in tandem9–11. Recent advancements in DNA synthesis techniques, and the resultant widespread accessibility to custom-made nucleic acid sequences12, allows to refine in silico strategies for the design of optimized transgenes. Taking advantage of the above features, this protocol is based on the replacement of the native miR hairpins of miR-17-92 cluster with other natural microRNAs hairpins, which, by virtue of their modular structure, are easily interchangeable. The resulting transgene is able to hitchhike the cell’s microRNA biogenetic machinery to express the desired array of microRNAs, and its contained size allows it to be fitted into any delivery vectors for practical cell delivery and therapeutic applications. Here we focus on a detailed protocol explaining steps to design, assemble and use these clusters for gene therapy purposes. The biological significance and mechanistic considerations of microRNA clustering are detailed in our prior manuscript concerning the use of these constructs against glioblastoma, a fatal brain cancer13.

Comparison with other methods

The delivery of microRNAs to target cells or tissues can be broadly divided into liposomal-mediated and vector-mediated. The former is short lived and exposes cells to often supraphysiologic amounts of microRNAs14. Also, the non-negligible toxicity encountered with the systemic delivery of microRNA mimics in a phase 1 cancer clinical trials15,16, has discouraged the use of multiple microRNAs combinations, and has thus significantly limited their clinical impact. On the contrary, gene-mediated delivery has the advantages of attaining more physiologic expression levels, can be regulated by tissue specific promoters, thus maximizing the expression in specific tissues, while sparing others, and generally allows for more prolonged expression. The limitations imposed by vectors’ packaging capacity can be overcome by condensing multiple microRNAs within short DNA sequences, and thus, the use of microRNA cluster structures is an attractive choice for maximizing the impact of microRNA modulation for both in vitro studies and in vivo applications. The polycistronic nature of certain microRNAs has been utilized for the overexpression of various arrays of inhibitory RNAs against HIV17, influenza18, cancer19, hepatitis20, or generic reporter genes21 (Table 1). In all cases, the purpose was to express synthetic inhibitory RNAs tailored at specific target genes, rather than recapitulating the physiological landscape and broad functions of natural microRNAs deregulated in diseases. Also, those studies relied heavily on elaborated cloning techniques, proving not immediately intuitive in their technical execution and possibly cumbersome for every-day applicability and adaptability to different gene therapy needs.

Table 1.

Previously published methods for multi-microRNA/siRNA overexpression

| microRNA scaffold | Replacement | Disease/target | Species | Mechanism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu, Y17 | miR-17-92 cluster | shRNAs | HIV | Human | Replacement of leading strands of native microRNAs with shRNAs |

| Chen, S18 | miR-126 | shRNAs | Influenza | Chicken | Substitution of leading strand of miR-126 with shRNAs |

| Askou, A19 | miR-106 cluster | artificial microRNAs | VEGF | Mouse | Substitution of native hairpins of the cluster with artificial microRNAs |

| Yang, X 20 | miR-17-92 | shRNA | HCV | Human | Replaced 5 hairpins with 5 sequences complementary to HCV genome |

| Wang, T 21 | miR-155 | artificial microRNAs | Reporter gene | Human | Tandem repetition of the miR-155 structure, each encoding a synthetic microRNA precursor |

| Zhang, N 26 | n/a | artificial microRNAs | SR45.1 | Thaliana | Artificial microRNA hairpins in tandem separated by tRNAs sequences |

Applications of the method

We have used this protocol to demonstrate that the combinatorial modulation of three (published data) to six (unpublished data) selectively chosen microRNAs normally expressed in healthy brain has a synergistic anticancer effect by simultaneously targeting multiple oncogenic proteins, overcoming their ability to rescue each other’s impaired function when targeted singularly13. We also show that these transgenes can be delivered in vivo by Adeno Associated Virus (AAV) vectors injection into intracranial brain tumors, with significant survival benefit in a mouse preclinical model (unpublished). This protocol is easy to execute and takes advantage of the modular structure of microRNAs genes. Accordingly, microRNA clusters can be dissected in silico into their functional components and rearranged into chimeric transgenes able to overexpress groups of multiple microRNAs. Because it is based on features that are common to all microRNAs, our method is generally applicable to any miRs of interest, and consequently is very versatile. Moreover, the core of this protocol is based on the in silico design of the transgene, reducing the need for molecular cloning to a minimum. We believe that this protocol provides an easy method for the engineering of virtually any combinations of microRNAs of choice into a transgene suitable for both in vitro and in vivo applications.

Limitations

This protocol has been optimized for delivery to human cells, using the human miR-17-92 sequence as a scaffold. Microprocessor (i.e. the microRNA-processing complex, made by proteins Drosha and DGCR8) is broadly conserved across animal and plant cells22, but it is possible that a species-specific scaffold sequence might work more proficiently in the corresponding cells.

We have decided to utilize miR-17-92 as an ideal scaffold for our transgenic clusters, since, among known microRNA clusters, it provides the highest number of microRNAs (six) within the shortest sequence of DNA (~ 1kb). This is important for practical reasons, mainly the limitations imposed by the packaging capacity of delivery vectors. We expect that other microRNA clusters (for example the miR-302/367 cluster) would work similarly.

Depending on the biological function of the microRNAs overexpressed by the transgene, it is possible that they might interfere with the basic biology of the cells used to produce virus particles (i.e. HEK293), and this can result in lower vector titers when cytotoxic or tumor suppressive microRNAs are used.

We have observed a progressive decrease of mature microRNA expression as the number of microRNAs encoded within the transgene increases. It is possible that as the transgene becomes larger, the cleavage efficacy of microprocessor might decrease. Notwithstanding, even if the level of each given microRNA is comparatively decreased when they are processed from a six hairpin structure as opposed to a single or a three-hairpin structure, we found that the inhibitory effect of each microRNA on their respective target is not different, and that the biological benefit of the microRNA summation is evident.

We have not tested transgenes encoding more than six hairpins. While we hypothesize that a larger number of microRNAs can be successfully expressed, this might be limited by packaging size as well as microprocessor efficiency.

In vivo injection of viral particles can potentially cause toxicity, either due to the infection itself, or due to off-target effects of the microRNAs in neighboring non tumor cells. We have not observed any toxicities in our experiments using intratumoral, intracranial AAV injection, and all mice tolerated the inoculation without any complications (i.e. seizures, abnormal behavior, weight loss or premature death). However, the observed preferential tropism for human cells of the AAV vector used in this study, (Supplementary Figure 2, unpublished data) might have masked potential toxicities.

Overview of the procedure

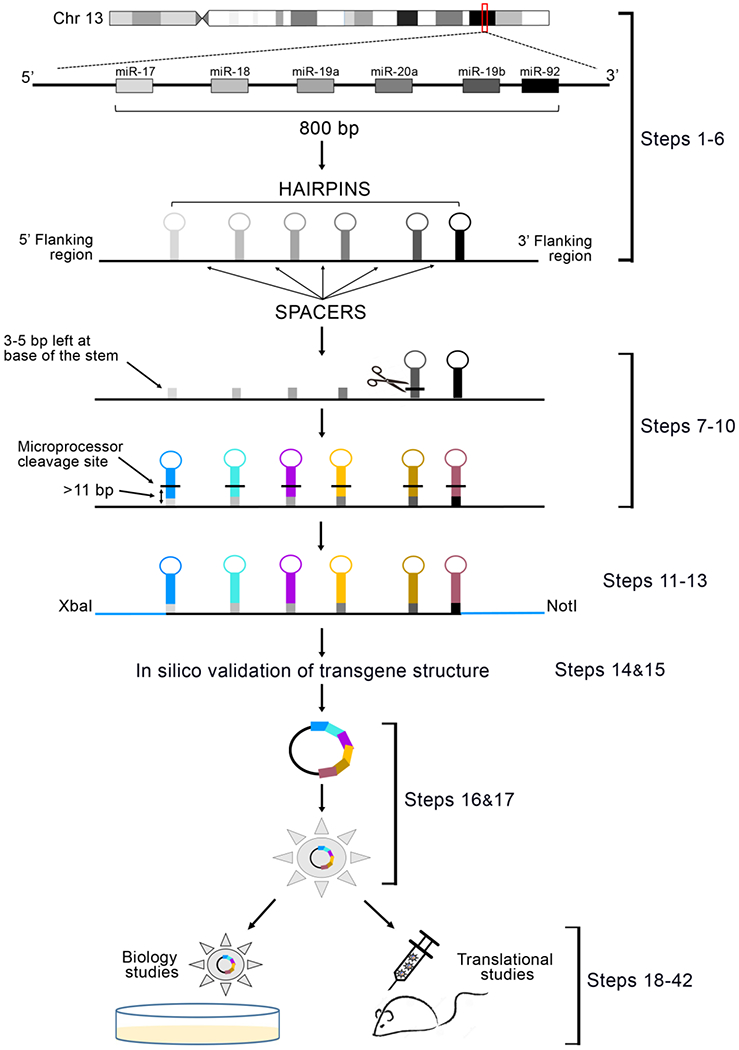

The key steps of this protocol are carried out in silico. First, the functional components of the miR-17-92 cluster (i.e. 5’ and 3’ flanking regions, microRNA hairpins and spacing sequences, i.e. sequences separating each hairpins from the neighboring ones) are mapped. In the next step, the sequences encoding native microRNA hairpins are replaced with full, non-modified, sequences encoding microRNAs hairpins of choice. Approximately 200 nucleotides of both the 5’ and 3’ flanking regions of the chimeric microRNA in position #1 are used to replace the original miR-17-92 flanking regions. This step (optional) is performed to decrease the carryover of genetic elements belonging to an oncogene (miR-17-92) into the new transgene. Each flanking region is fitted with restriction sequences of choice for future subcloning. The native sequences separating each hairpin in the original miR-17-92 transgene are maintained to facilitate the correct RNA folding of the transcript. The resulting transgene is then verified for appropriate two-dimensional folding and maintenance of the hairpin structures by in silico analysis. Finally, the transgene is obtained by DNA synthesis and is subcloned into the desired delivery vector for downstream verification of microRNA expression and biological applications (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Protocol Schema.

The genomic location of miR-17-92 cluster within human Chromosome 13 is marked with a red box (adapted from www.ensembl.org). Magnification of the region shows the configuration of the six native microRNA hairpins within the locus, and the schematic RNA structure of the native miR-17-92 cluster. Marked are the 6 hairpins (grey scale), as well as the spacer sequences separating each hairpin, and the flanking regions of the gene. The native hairpin sequences are removed, and only a 3-5 nucleotide sequence of their stem is maintained to function as an acceptor for the new desired chimeric hairpins (color-coded). It is critical that the microprocessor cleavage site for each substituting hairpin (black lines) is included in the pasted sequences to allow correct processing. The final configuration requires the presence of at least 11 base pair stem structure proximal to the microprocessor cleavage site. The native 5’ and 3’ flanking sequences of the locus are replaced with ~200 nucleotide sequences originally flanking the new microRNA in position #1. Restriction sites are added to the extremities of the transgene to facilitate downstream subcloning. The designed DNA sequence is then synthesized, cloned into a delivery vector of choice, and its function analyzed both in vitro and in vivo.

Experimental design

Choice of microRNA cluster:

This protocol is based on the genetic structure of the human miR-17-92 cluster, encoded in Chromosome 13. This particular cluster has been chosen because it has the highest number of miR hairpins (six) within the shortest DNA segment (~ 800 base pairs), among all other native microRNA cluster loci. This allows for a higher number of microRNA combinations.

Choice of substitute microRNAs:

The selection of microRNA hairpins to replace native ones in the transgenic cluster is completely dependent on the goals of the investigator. Any microRNA hairpins contains the intrinsic features necessary and sufficient to be accommodated within the transgene structure. We recapitulated the expression of several microRNAs expressed in normal brain (different combinations among miR-128, miR-124, miR-137, miR-7, miR-218 and miR-34a), but suppressed in glioblastoma, a brain cancer. Importantly, it is not necessary to reconstitute the full length of the cluster to maintain its functionality, and this protocol works well to overexpress any numbers or microRNAs between two and six.

Choice of appropriate control transgene:

For negative control, we used a transgene constituted by the same genetic scaffold as described above, but where the 20 nucleotide sequence encoding the leading microRNA strand of each hairpin was substituted with a scrambled sequence.

Choice of delivery vector:

For in vitro applications, we have mainly used a third-generation lentiviral vector (pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-copGFP), where the microRNA transgene is driven by a human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. For in vivo gene delivery, we have utilized an AAV-serotype 2 vector, with a CMV early enhancer/chicken β Actin promoter hybrid23 to drive the transgene expression. In general , any vectors can be used, as long as the packaging limit of the vector of choice is respected.

Downstream studies:

Verification of correct microRNA overexpression. After transgene delivery, transduced cells can be analyzed for the correct expression of each microRNA by quantitative RT-PCR or northern blot. It is recommended to wait at least 48 hours after transduction to allow sufficient time for microRNA processing

Verification of appropriate microRNA function. The biological activity of each overexpressed microRNA is best assessed by western blot of the target proteins. Alternatively, a luciferase reporter assay can be used, whereby the 3’UTR sequence of the reporter gene contains a specific recognition site for the microRNA(s) of interest.

Biological studies. Depending on the expected biological action of the microRNAs of interest, a wide array of functional studies can be performed: we have successfully tested cells for proliferation, apoptosis, clonal expansion, DNA repair, tumorigenicity in vivo, and response to chemotherapy13.

Materials

1. Bioinformatics

- Computer with internet access to the following open resources:

- miRBase (www.mirbase.org): This website provides a full repository of all annotated microRNA sequences for all species. CRITICAL STEP: for each hairpin, the program provides the specific nucleotides where microprocessor cleavage occurs.

- Ensembl Genome Browser 95 (www.ensembl.org): This website provides access to the full genomic DNA sequence of miR-17-92 cluster.

- RNAfold Web Server (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at): This program predicts the secondary structure of RNA sequences. CRITICAL STEP: this is important to verify the maintenance of the hairpin structures in the transgenic sequences.

- Software for transgene sequence design:

- DNA Star Lasergene-Sequence Builder tool (https://www.dnastar.com/manuals/installation-guide). Alternatively, any text editing software (i. e. Microsoft Word) can be used.

2. Biological material

Human cell lines HEK293 (ATCC Cat# CRL-1573, RRID:CVCL_0045) ! CAUTION The cell lines used in your research should be regularly checked to ensure that they are authentic and free of mycoplasma. ! CRITICAL: HEK293 cells are fundamental for the production of high titers of both lentivirus and AAV vectors.

Human primary glioma stem-like cells (GSCs) (GBM34 and GBM30 were a kind gift from Dr. E. A. Chiocca’s Laboratory at BWH) ! CAUTION The cell lines used in your research should be regularly checked to ensure that they are authentic and free of mycoplasma. We have authenticity checked regularly by IDEXX BioResearch which is provided as a submission file.

All animal experiments were performed in immunodeficient athymic mice (FoxN1 nu/nu, Envigo, South Easton, MA), ! CAUTION All animal experiments should be performed in accordance with federal and local guidelines and regulations. Our experiments were done in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations applied to the use of small rodents, and with approval by the Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

3. Reagents

The transgene constructs were designed in silico by the authors and obtained though DNA synthesis from Invitrogen GeneArt Gene synthesis services. The transgenes are received from vendor as DNA plasmid ready for subcloning into desired vectors.

Refer to the Supplementary methods section for a detailed list of reagents and procedures used for transgene cloning and viral vector packaging and preparation.

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS; Gibco, cat. no. 14190144).

Neurobasal Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 21103049).

GlutaMAX Supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 35050061)

B-27 Supplement (50X), minus vitamin A (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 12587010)

Animal-Free Recombinant Human EGF (PeproTech cat. no. AF-100-15)

Animal-Free Recombinant Human FGF-basic (154 a.a.) (PeproTech cat. no. AF-100-18B)

StemPro Accutase Cell Dissociation Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. A1110501)

TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 15596026) ! CAUTION TRIzol is extremely toxic if swallowed or in contact with skin or inhaled. Avoid breathing dust/fume/gas/mist/vapors/spray. Wash hands thoroughly after handling and wear protective wares.

RNA Miniprep Kits (Direct-zol, cat. no. R2050).

TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 4366596)

TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, no AmpErase UNG (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 4324018)

Ketamine HCl Injectable MDV 50mg/mL (Henry Schein, cat. no. 1296589)

Xylazine sterile solution 20 mg/mL (AnaSed injection, Akorn Animal Health)

Acepromazine Maleate Injection 500mg/50mL (10 mg/mL) (Henry Schein, cat. no. AH025XH)

-

Buprenex (buprenorphine hydrochloride) injection, solution 0.3 mg/mL.

! CAUTION All drugs used for animal experiments should be performed in accordance with federal and local guidelines and regulations. Our experiments were done in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations applied to the use of small rodents, and with approval by the Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Povidone iodine scrub solution (7.5% (wt/vol); Medline, cat. no. MDS093908)

4. Reagent setup:

Growth medium (for GSCs)

Take 500 ml of Neurobasal media and add 1/50 dilution (10ml) of B27 supplement. Add 1/100 (5 ml) of Glutamax from stock to get final concentration of 2 mM. Then add 10 µl each of EGF (20ng/ml) and FGF (20ng/ml) 100 µg/ml stocks. Add 1/100 dilution (5 ml) of Pen/Strep stock. Invert the bottle a few times to ensure thorough mixing of all components. Store the bottle at 2–8 °C in the refrigerator for no longer than 6 weeks.

5. Wet lab Equipment

0.6-mL Microcentrifuge tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 05-408-120)

1.5-mL Microcentrifuge tube (Eppendorf, cat. no. 022431081)

Corning Lambda Plus Single-Channel Pipettor (cat. nos. 07-764-700, 07-764-701, 07-764-702, 07-764-703, 07-764-705, 07-764-704)

Filtered pipette tips (10, 20, 200 and 1,250 μL; VWR, cat. nos. 10017-032, 10017-046, 10017-078, 10017-082)

Disposable serological pipettes (5, 10 and 25 mL; Greiner Bio-One, cat. nos. 606180, 607160, 760160)

15-mL conical centrifuge tubes (Falcon; Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 1495953A)

50-mL conical centrifuge tubes (Falcon; Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 1443222)

Isotemp 37 °C water bath (Fisher Scientific, model no. 2223)

Microcentrifuge refrigerated (Eppendorf, model no. 5424 R, cat. no. 5404000138)

Humidified CO2 incubator (5% (vol/vol) CO2, 37 °C) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 310)

SterilGARD biosafety cabinet (tissue culture hood; The Baker Company, model no. SG403A-HE)

Hemocytometer (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. Z359629-1EA)

Cover glasses (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 12-548-5P)

PCR tubes (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. CLS6571-960EA)

S1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 1852196)

StepOne Real-Time PCR System, Applied Biosystems (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 4376357)

Cell culture flask, 550 mL, 175 cm2, Red Filter screw cap, Cell star, sterile (Greiner Bio-One, cat. no. 660175)

Hamilton syringe, 5 µL, Model 65 RN SYR, Small Removable NDL, 22s ga, 2 in, point style 3 (Hamilton, cat. no. 87943)

Model 900LS Small Animal Stereotaxic Instrument (David Kopf instruments, model no. 900LS)

Reflex Clip Applier for 7mm Clips (World Precision Instruments, model no. 500343)

Tool sterilizer (Germinator 500; Braintree Scientific, cat. no. GER 5287-120V)

EASYstrainer, 40 µm-sterile (Greiner Bio-One, cat. no 542040)

Falcon 5 mL Round Bottom Polystyrene Test Tube, with Snap Cap, Sterile (Corning, cat. no 352058)

8X-50X Track Stand Stereo Zoom Parfocal Trinocular Microscope w Top & Bottom LED Lights (AmScope, model no. SKU: SF-2TRA)

Procedure

Structural analysis of miR 17-92 cluster and definition of its components TIME: 2 hours

CRITICAL STEP: The precise recognition of microRNA hairpins and their cleavage sites by microprocessor is the fundamental step for this protocol. Maintenance of the 2D structural integrity of the hairpins is essential for their correct processing

Retrieve the genomic sequence of human miR-17-92 cluster and export it to Sequence Builder or Microsoft Word for editing.

Access the sequence at: http://useast.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Location/View?db=core;g=ENSG00000215417;r=13:91350433-91351620;mr=13:91350445-91351602

Click on “export data”. Use default page settings. Confirm that genomic location is Chromosome 13, position 91350433 to 91351620.

Click “next” and select “Text” as output format. This opens a .txt file containing the FASTA sequence of the specified genomic region. CRITICAL STEP The presence of RNA regions flanking the hairpin are fundamental for correct microRNA processing24 . Select 200 nucleotides in the 5’ region upstream of the microRNA hairpin in position#1 and 200 nucleotides in the 3’ region downstream of the microRNA hairpin #6. In our experience, microRNA processing of even one single hairpin is significantly decreased when the flanking regions are <100-150 nucleotides.

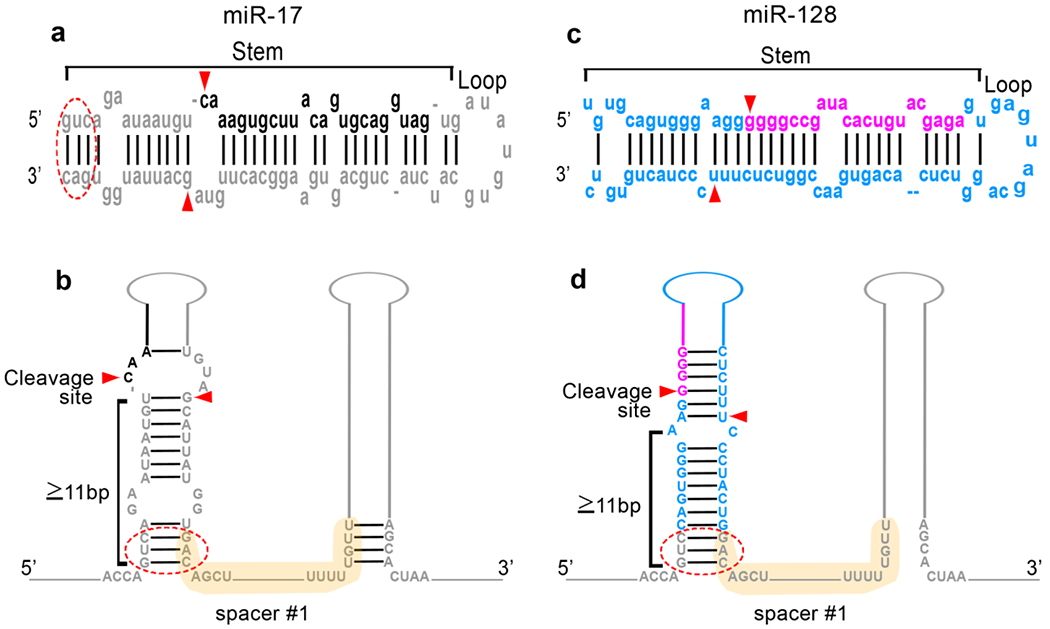

Obtain the sequence of each one of the 6 microRNA hairpins encoded in the cluster from miRBase. Make notice of the exact nucleotides at the site of microprocessor cleavage (this is color-coded in the website graphical output) (Figure 2a, c)

Map the six sequences obtained in step #5 against the full cluster sequence of step #1, to obtain the precise location of each hairpin, as well as any spacer sequences, and the boundaries with flanking regions, within the locus (Figure 1B, 2B). CRITICAL STEP It is fundamental to exactly mark the microprocessor cleavage sites for any hairpins, as this is crucial for the downstream design of the transgene and its correct processing.

Figure 2: Hairpin substitution and preservation of 2D structure.

a: The RNA sequence of miR-17, which is the hairpin in position #1 of the miR-17-92 cluster, as obtained from miRBase, is represented in grey. The two components of the hairpin (i.e the stem and the loop) are marked. In black is the sequence of the biologically active mature miR-17 within the hairpin. Red arrows represent the specific microprocessor cleavage points. The red circle denotes a 3-5 nucleotide region at the base of the native stem which is maintained in the transgenic sequence to facilitate the formation of the new chimeric hairpin. b: Schematic representation of the miR-17 hairpin within its native cluster structure, to show the stem component (labelled) and its length. The active miR sequence is color-coded in black. The spacer sequence separating hairpin#1 and hairpin#2 is shown in light yellow. c: The RNA sequence of miR-128, the microRNA used as the replacement in position #1, is represented as obtained from miRBase, in blue. In violet is the sequence of the biologically active mature miR-128 within the hairpin. Microprocessor cleavage sites are marked by red arrowheads. d: Representation of the appearance of position#1 of the cluster after miR-17 hairpin has been substituted with the miR-128 hairpin. In particular, the length of the stem proximal to the site of microprocessor cut has been maintained to 11 nucleotides or greater, by leaving 3 nucleotides from the original miR-17 stem sequence. The spacer sequence is maintained identical. The three-nucleotide making the base of the stem (red circle) is also maintained.

Replacement of native miR-17-92 hairpins with desired substitute hairpins- TIME: 1 hour

-

7.

Obtain sequences of the microRNAs of interest from miRBase. As described above, make notice of microprocessor cleavage sites (Figure 2c).

-

8.

Starting from hairpin #1 (the hairpin in the most 5’ position), delete the sequence encoding each native hairpin, except the first 3-5 nucleotides at the 5’ and 3’ ends of the hairpin still retaining a base pairing configuration (Figure 2c). CRITICAL STEP. This 3-5 nucleotide sequence allows the two regions flanking the microRNA to initiate a stem structure and function as an acceptor for the new chimeric microRNA hairpin (Figure 2a, c, d).

-

9.

Replace the deleted hairpin sequence with the one of the desired microRNA. CRITICAL STEP make sure to include at least 8 base pairs from the replacing hairpin, proximal to microprocessor cleavage site to allow for the formation of a stem of appropriate length (>11 base pairs) which is an essential requirement for correct microRNA processing25. (Figure 2d) ? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

10.

Repeat steps 8 and 9 for the desired number of microRNAs up to a total of six.

Substitution of flanking sequences- Time: 30 minutes

-

11.

Delete the original miR-17-92 5’ and 3’ flanking regions and replace them with 200 nucleotide sequences from the flanking regions of the chimeric microRNA placed in position #1. CRITICAL STEP The removal of the miR-17-92 flanking regions is done to minimize the use of sequences belonging to an oncogene, and are replaced with the flanking regions of the first chimeric microRNA inserted in the transgenic cluster (in this case miR-128).

-

12.

Add 6-8 nucleotides encoding a desired restriction site at both ends of the transgene (the sequence depends on the restriction enzymes of choice). We have routinely used XbaI (TCTAGA) and NotI (GCGGCCGC). CRITICAL STEP Verify that the selected restriction sites are not present within the transgene sequence.

This step allows for rapid cloning into an expression plasmid for DNA amplification. ? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

13.

Add 5 nucleotides of choice (the sequence is not important) at each end of the sequence to allow enough space for DNA cleavage by the restriction enzymes.

In silico validation of transgene structure TIME 15 minutes

-

14.

Paste the resulting sequence into the RNA secondary structure prediction software (RNAfold WebServer) and proceed with the standard, preset configuration.

-

15.

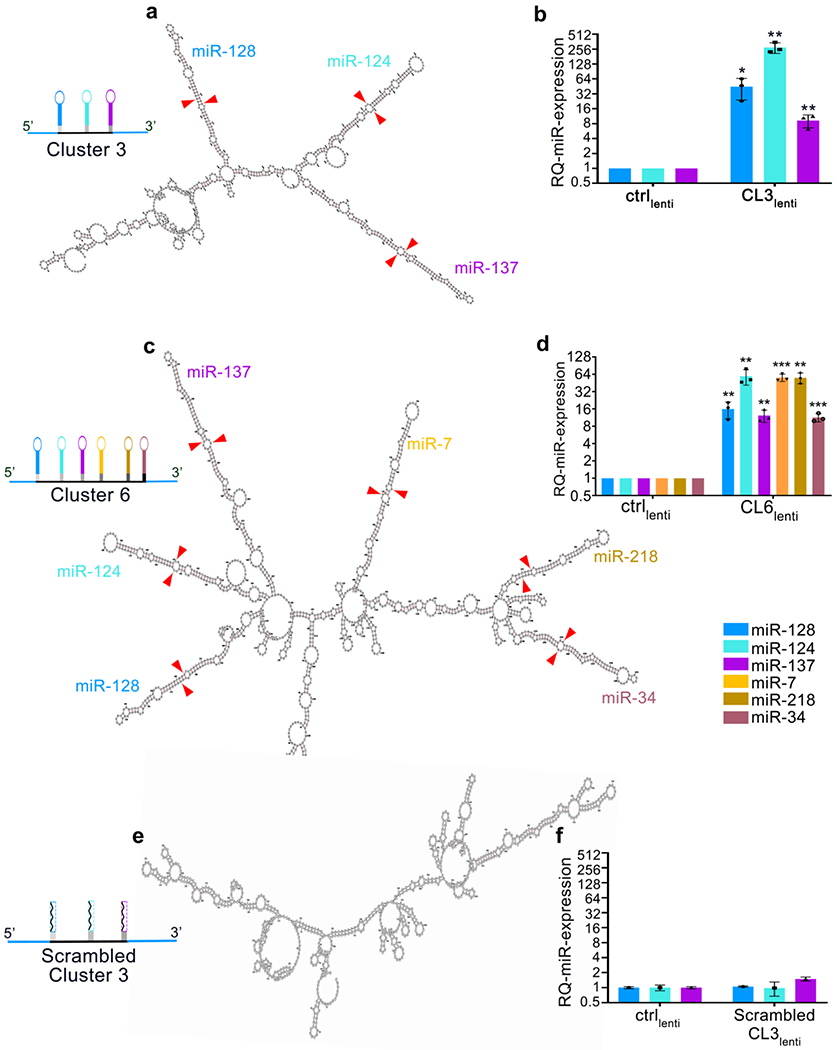

Analyze the graphic output by clicking the FORNA option. CRITICAL STEP Verify that each microRNA hairpin is properly structured and that there are at least 11 nucleotides of highly complementary stem proximal to the microprocessor cleavage site, without any branching points (Figure 3). In our experience, satisfaction of this requirement is an important predictor of successful microRNA processing. ? TROUBLESHOOTING

Figure 3: RNA structure prediction and transgene processing output.

a: Graphical output from RNAFold Web Server of a transgene containing the chimeric microRNA hairpins of miR-128, miR-124 and miR-137 (Cluster 3). Each hairpin is color-coded and labelled on the structure. Red arrow heads represent the cleavage points by microprocessor. b: Relative quantification of microRNA expression by RT-qPCR of G34 GBM cells infected with lentivirus expressing either negative control or Cluster 3 transgenes (adapted from Bhaskaran et al.13 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license). c: Graphical output of a transgene expressing the chimeric microRNA hairpins of miR-128, miR-124, miR-137, miR-7, miR-218 and miR-34a (Cluster 6 unpublished data). Each hairpin is color-coded and marked on the structure. Red arrow heads represent the cleavage points by microprocessor. d: Relative quantification of microRNA expression by RT-PCR of G34 GBM cells infected with lentivirus expressing either negative control or Cluster 6 transgenes (unpublished data). e: Predicted structure of a transgene derived from Cluster 3, containing a 20-nucleotide scrambled sequence replacing each microRNA of the transgene (Scrambled Cluster 3). Note the absence of hairpin formation, presence of branching points, and the absence of microRNA expression. f: Relative quantification of microRNA expression by RT-PCR of G34 GBM cells infected with lentivirus expressing either negative control or scrambled Cluster 3 transgene (unpublished data). For all experiments, reported are means ± SD of n=3 independent experiments. *=p<0.05; **=p<0.01; ***=p<0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). Ctrl= control; CL3= Cluster 3; CL6= Cluster 6.

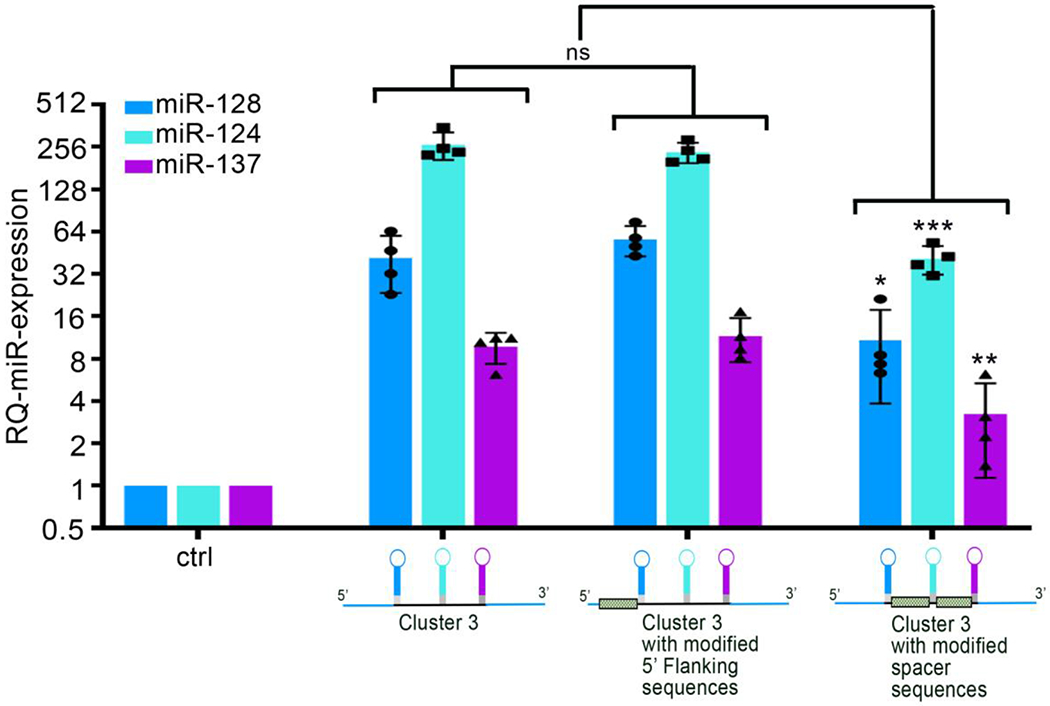

CRITICAL STEP Changing the flanking regions does not affect microRNA processing (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Effect of sequence modifications on the efficiency of transgene processing.

Relative quantification of microRNA expression by RT-qPCR from G34 glioblastoma cells infected with lentiviruses encoding different version of the Cluster 3 transgene. A cartoon representing the specific modification is depicted underneath each corresponding bar graph (unpublished data). Shaded bars in the cartoon represent the component of the transgene that has been modified in respect to the original Cluster 3 sequence obtained following the described protocol. The data shows that sequence changes in the 5’ flanking region of the transgene do not affect microRNA processing, while changes in the sequences separating microRNA hairpins (spacers) decrease the processing efficiency. Reported are means ± SD of n=3 independent experiments. *=p<0.05; **=p<0.01; ***=p<0.001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test); ns = non-significant

DNA synthesis TIME 4-6 hours

-

16.

Validated transgene sequence is submitted for DNA synthesis. This can be done in house for laboratories which have such capability. We have consistently had excellent results by outsourcing the synthesis of DNA to a vendor. PAUSE POINT After synthesis, the DNA can be stored at −20 °C indefinitely.

Transgene cloning and preparation of viral vectors TIME 3 days

-

17.

This part of the protocol follows the standard manufacturers’ instruction for DNA ligation, bacterial transformation, clone screening by restriction digestion, and packaging of viral vectors. Detailed steps and material for these stages are provided in the Supplementary methods section).

Transgene delivery

We first evaluate the proper functioning of the transgene by infection of cells in cultures. Secondarily, the preclinical characterization of the transgene is assessed in vivo by direct intratumoral injection of the viral vector in a mouse model of intracranial tumor. While lentivectors have provided a very reliable method to transduce cells in cultures, in our hands they have not shown good infectivity when delivered intracranially. In our experience with brain tumor cells, Adeno Associated Viruses serotype 2 are significantly more efficient for in vivo use, and thus they were used in that setting.

In vitro Time 45 minutes

-

18.

Incubate cancer cells with Accutase for 5 minutes at 37 °C until they are dissociated to single cells.

-

19.

Place 150,000 cells in a 15 ml conical tube in 5 ml of PBS and centrifuge at 300g for 5 minutes at 4 °C.

-

20.

Remove the supernatant with a Pasteur pipette, leaving a small pellet of cells undisturbed.

-

21.

Pipet 50 μl of concentrated lentivirus (totaling 5 x 107 viral particles) on top of the cell pellet. Gently flick the tube 3-5 times to mix the cells with the virus within the small ~ 50 μl volume. CRITICAL STEP: we have observed that performing the infection in a small volume within the 15 ml centrifuge tube allows for greater transduction compared to the inoculation of the same amount of virus when cells are dispersed in culture. ? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

22.

Incubate at 37 °C for 30 minutes with occasional flicking of the tube

-

23.

Resuspend the cells in 5 ml of pre-warmed culture medium and transfer them to culture flasks in a cell incubator set at 37 °C

In vivo Time 3 hours

-

24.

Anesthetize the mouse with Ketamine. ? TROUBLESHOOTING ! CAUTION make sure that the use of animals is performed according to protocols previously reviewed and accepted by the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC).

-

25.

Place mouse in the stereotactic apparatus.

-

26.

After locoregional disinfection of the scalp and using aseptic techniques, expose the area of previous intracranial inoculation of tumor cells

-

27.

Load 5x109 AAV2 particles in 5 ul PBS in a Hamilton syringe and assemble it into the stereotactic apparatus. CRITICAL STEP Because of the small volume allowed for intracranial injection, it is essential that the virus titer is > 1x109 to allow for significant infection.

-

28.

Introduce the needle intracranially following the exact same stereotactic coordinates used for inoculating tumor cells.

-

29.

Inject the virus solution with a rate of 1 μl/min.

-

30.

Leave needle in place for 5 minutes to decrease virus reflux along needle tract.

-

31.

At the end of surgery, place mouse in a warm cage until completely recovered from anesthesia ? TROUBLESHOOTING

Evaluation of microRNA expression and downstream biological effects.

The fundamental initial step to evaluate the proper processing of the transgene is to measure the level of mature microRNA produced after infection (Figure 3). This is followed by the analysis of downstream molecular and biological responses (e.g. protein analysis, cell proliferation and impact on survival in a suitable animal model) (Figures 5 and 6)

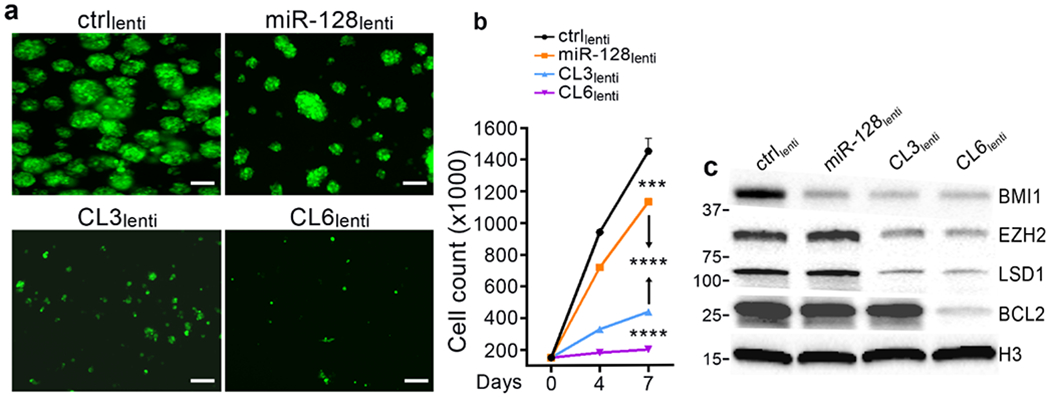

Figure 5: Biological evaluation of clustered transgenes in vitro.

Increasing the number of overexpressed microRNAs progressively inhibits GBM cell growth and expands targeting of crucial oncogenes. a: Fluorescent microscope (GFP) imaging of G34 glioblastoma cells expressing different microRNA combinations by lentiviral infection 7 days after plating (150,000/6-well plate); Scale bars = 100 μm. b: Cell count of cells in a. Reported are means ± SD of n=3 independent experiments. Both panel a and b show the progressive inhibitory effect exerted by either single microRNAs (miR-128) vs three-microRNA cluster, vs six-microRNA cluster. c: Representative western blot of protein lysates obtained from cells in a at time of cell count. BMI1 is a specific target of miR-128; EZH2 and LSD1 are specific targets of miR-124 and miR-137, respectively. BCL2 is a specific target of miR-34a (unpublished data). ***=p<0.001; ****=p<0.0001 (two-tailed Student’s t-test).

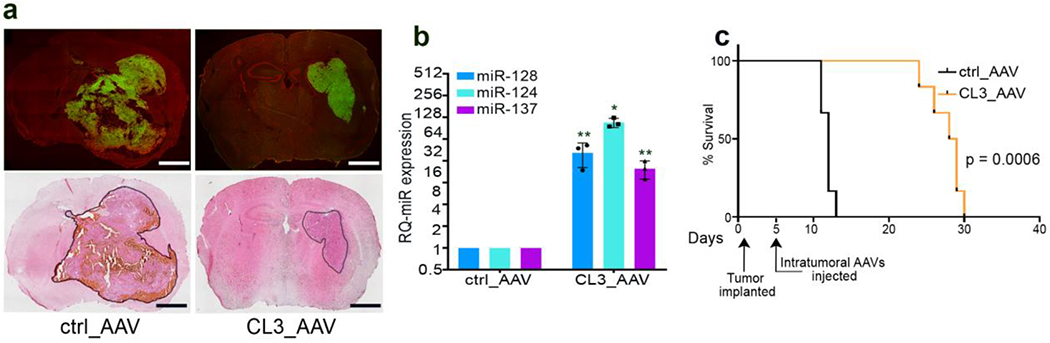

Figure 6: Delivery of clustered microRNA transgenes in vivo.

In vivo, intracranial delivery of a 3-microRNA cluster transgene via AAV vectors results in successful tumor transduction, microRNA overexpression, and significant antitumor effect with survival advantage. a: Representative pictures of frozen sections from athymic nude mouse brains seven days after intracranial, intratumoral inoculation of 5x109 particles of GFP-AAV2 vectors carrying either negative control or Cluster 3 transgenes (unpublished data). Upper row represents GFP expression, lower row represents hematoxilin and eosin staining, showing the smaller size of the tumor infected with AAV vectors carrying the 3-microRNA cluster. Scale bars = 1 mm. b: Relative expression of the three microRNAs encoded by Cluster 3 transgene in the tumor cells recovered from the brains in panel A (unpublished data). Reported are means ± SD from n=3 mice per group. *=p<0.05; **=p<0.01; (two-tailed Student’s t-test). c: Kaplan Meier survival curve of the mice in a (unpublished data). The timing of intracranial tumor implantation and intratumoral virus injection are marked along the X axis. n=6 mice/group. Eight mice per group (control vs Cluster 3 groups) were inoculated with AAVs. Two mice per group were sacrificed for histology examination and not counted towards the analysis of survival . All animals tolerated the procedure well and none died unexpectedly or showed signs of distress or toxicity. All deaths were due to tumor progression. All animal experiments were done in compliance with all relevant ethical regulations applied to the use of small rodents, and with approval by the Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

In vitro: TIME 3 hours

-

32.

After lentiviral infection, cell lines stably expressing the microRNA transgene are sorted by GFP-mediated FACS and expanded in culture. ? TROUBLESHOOTING

-

33.

At the desired endpoint, cells are collected and total RNA is extracted using Trizol or other available RNA extraction kits compatible with microRNA isolation. CRITICAL STEP Wait at least 48 hours before cell sorting, to allow time for full GFP expression from infected cells. We routinely check for microRNA expression, level of target expression and cell proliferation and at least 5 days after infection.

-

34.

Reverse transcribe the RNA using a Taqman microRNA-specific reverse transcription kit. After obtaining cDNA, perform qRT-PCR with microRNA-specific Taqman microRNA assays (thermofisher). We analyze the expression data with an ABI Step One Plus Real time PCR system. U6 small RNA is used as a housekeeping gene control. ? TROUBLESHOOTING

Ex vivo TIME 6 hours

-

35.

Euthanize the animal at the desired time point for evaluation of transgene expression in target cells. ! CAUTION make sure that the use of animals is performed according to protocols previously reviewed and accepted by the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC).

-

36.

Perfuse the brain with PBS through a transcardiac infusion of 10 ml ice-cold PBS to remove blood.

-

37.

Remove the brain form the skull and isolate the hemisphere which had been previously inoculated with the tumor and the virus particles.

-

38.

Using a bench-top magnifying lens (AmScope, model no. SKU: SF-2TRA), grossly isolate the tumor tissue from normal brain and place in ice-cold PBS.

-

39.

Incubate the tissue with Accutase for 1 hour at 37°C, then dissociate to single cells passing the tissue through a fire-polished Pasteur pipette, and filter through a 40 µm cell strainer.

-

40.

Sort GFP-positive cells by FACS.

-

41.

Extract the RNA as described in step 33

-

42.

Proceed with microRNA detection and expression analysis as detailed in step 34

Troubleshooting (Table 2)

Table 2.

Troubleshooting

| Step | Problem | Possible reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9 and 15 | Failure to process specific microRNAs | 1. Hairpin Stem too short 2. Spacer sequence too short |

1. Add a number of complementary base pairs until the stem is at least 11 base pair long 2. Add at least 20 nucleotides to the 2 spacer sequences upstream AND downstream the corresponding hairpin. 3. Change the location of the hairpin within the transgene |

| 12 | The desired restriction site is also present within the transgene | Change 1-2 nucleotides in the internal sequence recognizing the desired restriction site. This can NOT be done if the sequence is within the mature microRNA and SHOULD not be done if it is within the hairpin sequence as it might decrease processing> | |

| 21 | Minimal transgene expression | 1. Low rate of infection 2. Inactive promoter |

1. Expose cells to virus up to 6 hours. Do not exceed 6 hours as cell viability will be reduced. 2. Increase virus titer 3. Change recipient cells 4. Consider changing transgene promoter |

| 24 | Animal gasping under anesthesia | Excessive use of ketamine | Decrease dose of Ketamine |

| 31 | In vivo toxicity | Off-target effect of microRNA on bystander normal cells | 1. Select microRNAs that are already constitutionally expressed in normal tissue 2. Use tumor-specific promoter to increase tumor-specific overexpression |

| 32 and 34 | Low RNA yield | 1. Poor cell growth due to microRNA toxicity 2. RNA degradation |

1. Pool cells from multiple infections 2. Use RNAse-free technique and DPEC-treated water |

Because of the modular characteristic of microRNA hairpins, we have consistently observed that satisfactorily in silico analysis of the transgene structure was 100% predictive of successful transgene processing. It is possible that in some instances the folding and processing of certain microRNAs might not be as anticipated. In such cases, we suggest moving the sequence encoding for the specific microRNA hairpin to a different position within the transgene, as this might produce a more favorable folding of the primary sequence. Another option, more tailored to microRNAs with a short stem, is to lengthen the stem acceptor sequence by adding several more complementary base pairs (in addition to the three used as default in the standard protocol). This will facilitate the formation of the hairpin and its cleavage.

We encourage the use of vectors that simultaneously express a reporter gene (RFP, GFP, antibiotic resistance gene) to confirm appropriate cell transduction in case of low or absent microRNA expression. In cases where the reporter gene is present, but no microRNAs are detected it is important to rule out whether the problem is at the microRNA processing or at the transcription level. PCR of the primary transcript should be performed to exclude the latter. This can be done by designing sequence-specific primers encompassing the 5’ flanking region of the cluster (Forward primer) and the first microRNA hairpin (Reverse primer), after removing any genomic DNA carryover by DNAse digestion (Supplementary Figure 4). Also, the choice of the promoter driving the transgene expression should be carefully made, depending on the expected or known activity of that promoter in the cells of interest. We have observed very good expression levels with human CMV promoter, but other RNA polymerase 2 promoters such as EF1a or SV40, or cell-specific promoters are all compatible with the cassette. In cases of low transduction efficiency, increase the amount of viral particles per infection, being careful to monitor for cell toxicity. Finally, to reduce the possibility of toxicity in vivo, it is recommended to employ microRNAs that are already normally expressed in the healthy tissue (the brain in our case), in order to minimize off-target effects. Another alternative is to use a tumor-specific promoter to drive the transcription of the transgene, limiting its expression in normal cells

Timing

Steps 1-6: analysis of scaffold structure: 2 hours

Steps 7-10: substitution of microRNA sequences: 1 hour

Steps 11-13: substitution of flanking sequences: 30 minutes

Steps 14-15: in silico validation of transgene structure: 30 minutes

Step 16: DNA synthesis: 4-6 hours

Step 17 (Supplementary Methods): DNA subcloning into delivery vectors: 3 days

Step 18-31: Transgene delivery: 45 minutes (in vitro); 3 hours (in vivo)

Step 32-42: Evaluation of transgene expression: 3 hours (in vitro); 6 hours (ex vivo)

Anticipated results

The design of transgenic microRNA clusters described in this protocol allows for reliable and predictable overexpression of multiple microRNAs with retention of their full biological functions, including their multitargeting properties. We have used this strategy to simultaneously re-establish the expression of three neuronal microRNAs (miR-124, miR-128 ad miR-137) in GBM cells, with resulting inhibition of multiple key oncogenes and significant antitumor effect13. Adherence to this protocol routinely yields RNA sequences with favorable structural conformation and effective processing into mature microRNAs (Figure 3). Depending on the basal expression level of each microRNAs in target cells, a 10-100 fold increase in expression is generally achieved by the transgene. We have also demonstrated the flexibility of our protocol by expanding the pool of chimeric microRNAs from three up to six, all of which displayed robust expression in GBM cells. Data regarding a 3-microRNA cluster has already been publishded13. Data on the 6-microRNA transgene has not been previously unpublished. This approach has confirmed the biological relevance of reconstituting the expression of progressively larger clusters of microRNAs (Figure 5, unpublished data). Interestingly, when multiple microRNAs share the same target, their combination does not appear to be synergistic nor additive against that specific mRNA. For example, SP1 and JAG1 are independently targeted by miR-124, miR-128 and miR-137. Yet, the level of inhibition of these two oncogenes does not significantly increase when the three microRNAs are overexpressed together, suggesting that microRNA clustering works preferentially by expanding the targetome rather than strengthening the inhibition on shared targets (Supplementary Figure 1). Importantly, we have shown the versatility of our transgenic construct by cloning the 3-microRNA transgene (Cluster 3) into Adeno Associated Virus (AAV) vectors. In vivo, intratumoral inoculation of these AAV vectors resulted in tumor cell transduction, expression of transgenic microRNAs, and marked antitumor effect in a mouse GBM model (Figure 6, unpublished data). It is expected that any vectors commonly used in gene delivery support the expression of the transgenic cassette, for both in vitro and in vivo use. The determination of the best vectors depends on the characteristics of each biological context (i.e. in vitro vs in vivo; tumor cells vs non -tumor cells; localized vs systemic targeting, etc.) and is beyond the scope of this protocol. The modular structure of the miR-17-92 scaffold (Figures 1 and 2) is expected to support the overexpression of any desired microRNA combinations, for a number of hairpins at least up to six.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Effect of microRNA clusters on common targets

Representative western blot from G34 GBM cells after stable expression of either negative control, single microRNAs or their combination by lentiviral infection. SP1 and JAG1 are GBM-relevant oncogenes that are independently targeted by each one of the three microRNAs. While each microRNA, as expected, decreases the level of both proteins, the combination of microRNAs does not further increase the downregulation obtained by single targeting. Reproduced with modifications from Bhaskaran et al.13 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license

Supplementary Figure 2: Histologic analysis of AAV-infected brain tumors.

Representative confocal microscope images of intracranial human GBM in nude mice three days after stereotactic intratumoral inoculation of 5x109 AAV particles encoding Cluster 3 transgene. In the upper row are displayed images at 1x magnification (scale bar = 1 mm); In the lower row is displayed the 20x magnification of the corresponding white boxed section (scale bar = 100 μm). Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain shows the brain/tumor interface, and the absence of grossly evident brain tissue necrosis or damage after virus infection. Yellow line denotes the edges of the entire sectioned brain in the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP) channels.

Supplementary Figure 3. Temporal pattern of transgenic microRNA expression in vivo.

Real Time RT-PCR quantification of mature microRNA expression in human G30 GBMs recovered from mice brains at the times labelled in the X axis. Day 7 and Day 19 refers to number of days after the intracranial infection with the AAV vectors. Control refers to ex-vivo tumors infected with control AAV expressing scrambled microRNA transgene and analyzed at Day 7 after infection. Represented are Mean ± SD from n=3 independent experiments. *** = p<0.001 (Student’s t-test, 2 tails).

Supplementary Figure 4: Strategy to verify transgene expression.

a: Cartoon schematizing the genomic configuration of the lentiviral vector used to overexpress microRNAs. The GFP transgene is downstream to an EF1-responsive element, while the Cluster 3 primary transcript is downstream of the CMV promoter. Colored arrows represent primer sequences used for the RT-qPCR. Green arrows represent primers for the GFP sequence. Black arrows represent primers for the microRNAs cluster transgene (note that the forward primer is in the 5’ flanking region, while the reverse primer is in the miR-128 hairpin sequence). b: Relative quantification of microRNA expression at different timepoints after intracranial implantation. G34 cells previously implanted intracranially in athymic mice were isolated from the brain at time of mouse euthanasia (either at day 12 or at day 25) and the expression of cluster 3 transgene was measured against that of cells expressing negative control and against parental Cluster 3 cells at time of implantation (day 1). Reported are Mean ± SD from three independent experiments. c: RT-qPCR showing expression of GFP transgene from cells in panel b. d: RT-qPCR showing expression of primary Cluster 3 sequence from cells in panel b. For both c and d, reported are mean + SE from one representative experiment in technical triplicates. *=p<0.05; ***=p<0.001 (Student’s t-test, 2 tails). While the expression of GFP remains stable across all time points, the expression of the microRNA transgene decreases over time, reflecting the observed progressive decrease in mature microRNA overexpression.

(Reproduced with modifications from Bhaskaran et al.13 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NINDS grant K08NS101091 to PP.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study which are not directly available within the paper (and its supplementary methods files) will be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. This includes DNA sequences of all transgenes used in this study.

References

- 1.Wu YE, Parikshak NN, Belgard TG. and Geschwind DH. Genome-wide, integrative analysis implicates microRNA dysregulation in autism spectrum disorder. Nat Neurosci. 19,1463–1476 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esteller M Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 12, 861–874 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moradifard S, Hoseinbeyki M., Ganji SM & Minuchehr Z. Analysis of microRNA and Gene Expression Profiles in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Sci Rep. 8, (4767), (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calin GA et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99, 15524–15529 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer Nat Rev Genet. 10, 704–714 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambros V microRNAs: tiny regulators with great potential. Cell. 107, 823–826 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treiber T, Treiber N. & Meister G. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis and its crosstalk with other cellular pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20, 5–20 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krek A et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. , 37:495–500 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He L et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature 435, 828–833 (2005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barroso-del Jesus A, Lucena-Aguilar G, and Menendez P. The miR-302–367 cluster as a potential stemness regulator in ESCs. Cell Cycle 8: 394–8 (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landais S, Landry S, Legault P, and Rassart E. Oncogenic potential of the miR-106-363 cluster and its implication in human T-cell leukemia. Cancer Res. 67, 5699–707 (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunjapur A,M, Pfingstag P.and Thompson NC. Gene synthesis allows biologists to source genes from farther away in the tree of life. Nat Commun. 9, 4425 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhaskaran V et al. The functional synergism of microRNA clustering provides therapeutically relevant epigenetic interference in glioblastoma. Nat. Commun 10 (1):442 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin HY. et al. . Transfection of microRNA mimics should be used with caution. Front Genet. 6:340. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00340 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beg MS. et al. Phase I study of MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, administered twice weekly in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 35, 180–188 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Zandwijk N et al. Safety and activity of microRNA-loaded minicells in patients with recurrent malignant pleural mesothelioma: a first-in-man, phase 1, open label, dose-escalation study. Lancet Oncol. 18, 1386–1396 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu YP, Haasnoot J, Brake O, Berkhout B, and Konstantinova P. Inhibition of HIV-1 by multiple shRNAs expressed from a single microRNA polycistron. Nucleic Acid Res. 36, 2811–24 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen SC., Stern P, Guo Z, Chen J. Expression of Multiple Artificial MicroRNAs from a Chicken miRNA126-Based Lentiviral Vector. PLoS ONE, 6(7):e22437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022437 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Askou AL et al. Multigenic lentiviral vectors for combined and tissue-specific expression of miRNA and protein-based antiangiogenic factors. Mol. Ther. Methods Cin. Dev 2, 14064 doi: 10.138/mtm.2014.64 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X, Marcucci K, Anguela X and Couto LB Preclinical Evaluation of An Anti-HCV miRNA Cluster for Treatment of HCV Infection. Mol. Ther 21, 588–601 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang T, Xie Y, Tan A, Li S, and Xie Z Construction and Characterization of a Synthetic MicroRNA Cluster for Multiplex RNA Interference in Mammalian Cells. ACS Synth. Biol, 5, 1193–1200 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brate J et al. Unicellular origin of the animal microRNA machinery. Curr biol. 22, 28(20):3288–3295.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.018. (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexopoulou AN, Couchman JR, and White JR. The CMV early enhancer/chicken β Actin (CAG) promoter can be used to drive transgene expression during the differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells into vascular progenitors. BMC Cell Biol. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-2. (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ZenG Y and Cullen BR Efficient Processing of Primary microRNA Hairpins by Drosha Requires Flanking Non structured RNA Sequences. J. Biol. Chem 280, (30), 27595–27603, (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han J et al. Molecular Basis for the Recognition of Primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 Complex. Cell 125, 887–901, (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang N et al. Engineering Artificial MicroRNAs for Multiplex Gene Silencing and Simplified Transgenic Screen. Plant Physiol. 178, 989–1001, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Effect of microRNA clusters on common targets

Representative western blot from G34 GBM cells after stable expression of either negative control, single microRNAs or their combination by lentiviral infection. SP1 and JAG1 are GBM-relevant oncogenes that are independently targeted by each one of the three microRNAs. While each microRNA, as expected, decreases the level of both proteins, the combination of microRNAs does not further increase the downregulation obtained by single targeting. Reproduced with modifications from Bhaskaran et al.13 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license

Supplementary Figure 2: Histologic analysis of AAV-infected brain tumors.

Representative confocal microscope images of intracranial human GBM in nude mice three days after stereotactic intratumoral inoculation of 5x109 AAV particles encoding Cluster 3 transgene. In the upper row are displayed images at 1x magnification (scale bar = 1 mm); In the lower row is displayed the 20x magnification of the corresponding white boxed section (scale bar = 100 μm). Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) stain shows the brain/tumor interface, and the absence of grossly evident brain tissue necrosis or damage after virus infection. Yellow line denotes the edges of the entire sectioned brain in the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP) channels.

Supplementary Figure 3. Temporal pattern of transgenic microRNA expression in vivo.

Real Time RT-PCR quantification of mature microRNA expression in human G30 GBMs recovered from mice brains at the times labelled in the X axis. Day 7 and Day 19 refers to number of days after the intracranial infection with the AAV vectors. Control refers to ex-vivo tumors infected with control AAV expressing scrambled microRNA transgene and analyzed at Day 7 after infection. Represented are Mean ± SD from n=3 independent experiments. *** = p<0.001 (Student’s t-test, 2 tails).

Supplementary Figure 4: Strategy to verify transgene expression.

a: Cartoon schematizing the genomic configuration of the lentiviral vector used to overexpress microRNAs. The GFP transgene is downstream to an EF1-responsive element, while the Cluster 3 primary transcript is downstream of the CMV promoter. Colored arrows represent primer sequences used for the RT-qPCR. Green arrows represent primers for the GFP sequence. Black arrows represent primers for the microRNAs cluster transgene (note that the forward primer is in the 5’ flanking region, while the reverse primer is in the miR-128 hairpin sequence). b: Relative quantification of microRNA expression at different timepoints after intracranial implantation. G34 cells previously implanted intracranially in athymic mice were isolated from the brain at time of mouse euthanasia (either at day 12 or at day 25) and the expression of cluster 3 transgene was measured against that of cells expressing negative control and against parental Cluster 3 cells at time of implantation (day 1). Reported are Mean ± SD from three independent experiments. c: RT-qPCR showing expression of GFP transgene from cells in panel b. d: RT-qPCR showing expression of primary Cluster 3 sequence from cells in panel b. For both c and d, reported are mean + SE from one representative experiment in technical triplicates. *=p<0.05; ***=p<0.001 (Student’s t-test, 2 tails). While the expression of GFP remains stable across all time points, the expression of the microRNA transgene decreases over time, reflecting the observed progressive decrease in mature microRNA overexpression.

(Reproduced with modifications from Bhaskaran et al.13 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license)