Abstract

Background:

Geriatric patients, age ≥65, frequently require no operation and only short observation after injury; yet many are prescribed opioids. We reviewed geriatric opioid prescriptions following a statewide outpatient prescribing limit.

Methods:

Discharge and 30-day pain prescriptions were collected for geriatric patients managed without operation and with stays less than two midnights from May and June of 2015 through 2018. Patients were compared pre- and post-limit and with a non-geriatric cohort aged 18–64. Fall risk was also assessed.

Results:

We included 218 geriatric patients, 57 post-limit. Patients received fewer discharge prescriptions and lower doses following the limit. However, this trend preceded the limit. Geriatric patients received fewer opioid prescriptions but higher doses than non-geriatric patients. Fall risk was not associated with reduced prescription frequency or doses.

Conclusions:

Opioid prescribing has decreased for geriatric patients with minor injuries. However, surgeons have not reduced dosage based on age or fall risk.

Introduction

Recognition and awareness surrounding the opioid epidemic have dramatically altered pain management practices in the United States, both legislatively and clinically. From a legislative perspective, most states have implemented acute prescribing limits to restrict the quantity and/or duration of opioids that can be prescribed for acute pain.1 In August 2017, Ohio implemented an opioid prescribing limit, restricting outpatient prescriptions for acute pain to a duration of 7 days and a total of 210 morphine equivalent doses (MEDs) – the equivalent of twenty-eight 5mg oxycodone tablets. The medical and surgical community has also recognized culpability due to widespread prescribing practices. To help establish responsible perioperative prescribing practices going forward, physician groups have developed evidence-based guidelines for opioid prescribing in the setting of elective surgery.2 Guidelines for opioid prescribing after trauma, however, are lacking, and contemporary opioid prescribing practices for the trauma population are relatively unknown.

Excess opioid administration is particularly concerning for older patients. Opioids are included on the American Geriatrics Society Beers List of potentially inappropriate medications for older patients, and recommended to be used with caution in patients with history of fall or fracture.3 According to the national trauma databank, patients ages 65 and older make up roughly 30% of injury-related admissions to trauma centers. Furthermore, patients who are minimally injured, which we defined as those who do not require an operation within 30 days and have a hospital length of stay of less than two midnights, are at risk for persistent opioid use after injury.4,5 Therefore opioids should only be sparingly prescribed. In our institution, minimally injured patients encompass approximately 60% of trauma-related encounters. Discharge prescribing is a shared responsibility of emergency department and trauma physicians. This leads to considerable provider variability in this population and underscoring the need for research into opioid prescribing practices for these patients.

Our study aimed to assess prescribing patterns in geriatric trauma patients in this minimally injured category, especially surrounding the new opioid prescribing limit. Our objectives were (1) to assess the frequency and amount of opioid prescriptions to minimally injured geriatric trauma patients before and after the prescribing limit, (2) to compare opioid prescribing practices between geriatric and non-geriatric patients, and (3) to compare geriatric patients with fall mechanism or a prior fall history to those geriatric patients without these fall risks. We hypothesized first, that the opioid prescribing limit would reduce both opioid prescriptions as well as dosages, second, that geriatric patients would receive fewer opioid prescriptions and lower dosages than non-geriatric patients, and finally, that geriatric patients with fall mechanism or fall history would receive opioid prescriptions less frequently and at lower doses than geriatric patients without falls.

Methods

A single-center retrospective study analyzing opioid prescribing practices in minimally injured trauma patients was performed with a focus on the care of geriatric patients (age ≥65). The study took place at MetroHealth Medical Center, an established urban academic level 1 trauma center that evaluates and treats approximately 5000 trauma patients annually. The population included all adult patients undergoing trauma evaluation in the months of May in 2015–2018. To obtain a larger sample of geriatric patients for comparison, the inclusion period for patients age ≥ 65 was extended to June of those years. These months were selected due to expected higher trauma volume in the general population, temporal distance from the start date of Ohio's acute prescribing limit in August 2017, and potentially decreased impact of the “July Effect,” or resident physician inexperience affecting prescribing behavior. Patients were included if they were evaluated for trauma and discharged to their baseline living situation in fewer than two midnights and did not undergo surgery or interventional radiology procedures under general anesthesia within 30 days of injury. Patients who underwent repair of injuries such as lacerations under local anesthetic or procedural sedation were included. A length of stay less than two midnights was chosen to be consistent with observation status rather than inpatient admission. Patients requiring operations within the following 30 days were excluded to limit confounding from additional medical or surgical needs. Patients who died during index admission, pregnant patients, prisoners, and patients discharged to police custody, against medical advice, or to a higher level of care than baseline (e.g. to acute rehabilitation) were also excluded. During the years analyzed, no specific opioid prescribing protocol existed for trauma patients at our center.

The primary outcome was frequency of prescription and dosage of opioids at hospital discharge. Dosages were recorded in units of morphine equivalent doses (MEDs). Secondary outcomes included follow-up encounters within 30 days and post-discharge prescriptions during this timeframe. For objective 1, comparisons were performed between geriatric patients seen before the prescribing limit went into effect and patients seen after the law. For objective 2, geriatric patients were compared to the non-geriatric cohort of patients. For objective 3, geriatric patients with a fall or fall history were compared to geriatric patients without any documented history of falls.

Demographics were collected including age, race, and gender. Medical, social, and psychiatric history was collected including mental illness, chronic pain and related prescriptions, substance abuse including alcohol screen at admission, and prior falls. Mechanism of injury was collected and a composite variable of fall mechanism or fall history was created to identify a cohort of patients at risk of future falls.

Analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM, v24). Chi square tests compared proportions of categorical variables. Mann-Whitney U tests compared continuous variables. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. This study was approved by the MetroHealth Institutional Review Board.

Results

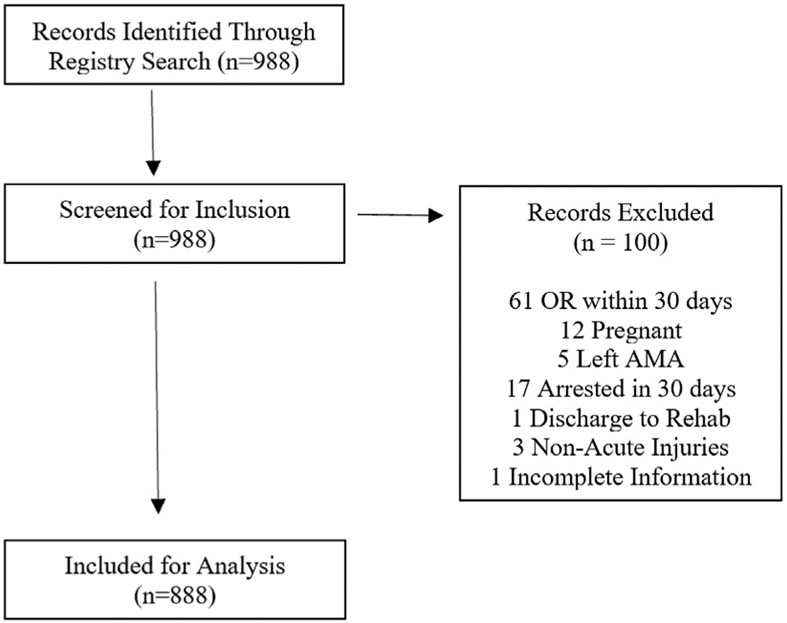

A total of 888 patients met inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of these patients, 218 were geriatric and 670 were non-geriatric. Geriatric patients were most commonly injured by falls, 159 (73%). Inpatient observation was required in 38 (17%) of geriatric cases and the remainder were discharged from the emergency department. Table 1 shows comparison of the geriatric cohort before and after the opioid prescribing limit. Fifty-seven geriatric patients were included in the post-law subgroup. Patients received fewer discharge opioid prescriptions post-limit (16% vs 30%, p = 0.032), and when prescribed, they received fewer MEDs (90 vs 225, p = 0.039). Timing and frequency of follow-up encounters did not change post-limit. There was no significant difference in the frequency of clinic opioid prescriptions within 30 days, but doses were significantly reduced (105 vs 375, p = 0.029).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram describing study inclusion.

Table 1.

Geriatric prescribing before and after Ohio's acute prescribing limit.

| 2015–2017 (n = 161) | 2018 (n = 57) | P -value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (IQR) | 76 (69–84) | 73 (68–86) | 0.758 |

| Female | 87 (54.0%) | 33 (57.9%) | 0.645 |

| White | 123 (80.4%) | 48 (85.7%) | 0.425 |

| Admitted | 31 (19.3%) | 7 (12.3%) | 0.31 |

| Blunt Injury | 158 (98.1%) | 56 (98.2%) | 0.958 |

| Fall | 116 (72.0%) | 43 (75.4%) | 0.729 |

| Fall Hx | 43 (26.7%) | 21 (36.8%) | 0.149 |

| Chronic Pain | 26 (16.1%) | 17 (29.8%) | 0.026 |

| EtOH Abuse | 17 (10.6%) | 8 (14.0%) | 0.479 |

| DC Opioid Prescription | 49 (30.4%) | 9 (15.8%) | 0.032 |

| DC MEDs | 225 (113–338) | 90 (60–128) | 0.039 |

| DC MEDs Over 210 | 28 (53.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0.029 |

| DC Ancillary Pain Med | 44 (27.3%) | 17 (29.8%) | 0.733 |

| Any 30d Followup | 136 (84.5%) | 45 (78.9%) | 0.34 |

| Clinic Narcotics | 14 (15.9%) | 4 (13.3%) | 0.999 |

| Total Clinic MEDs | 375 (150–530) | 105 (100–119) | 0.029 |

DC: Discharge.

MEDs: Morphine Equivalent Dosage.

Values reported as percentages or medians with interquartile range.

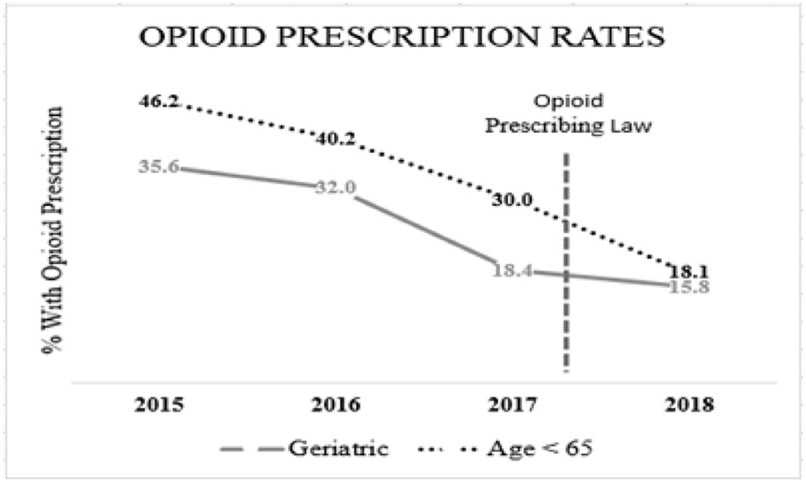

Table 2 shows the geriatric cohort compared with non-geriatric minimally injured trauma patients. Geriatric patients were more commonly female (55% vs 35%, p < 0.001), of white race (78% vs 58%, p < 0.001), and had increased history of falls (29% vs 3%, p < 0.001) and chronic pain (20% vs 12%, p = 0.002) respectively. Non-geriatric patients had higher rates of substance abuse history (43% vs 14%, p < 0.001) and positive admission alcohol screens (19% vs 10%, p = 0.002). Geriatric patients had fewer discharge opioid prescriptions over the study period than non-geriatric patients (27% vs 35%, p = 0.025); however, geriatric patients received a greater quantity of opioids in MEDs when discharge opioids were prescribed (150 vs 113, p < 0.046). 30-day clinic opioid prescriptions and MEDs were similar between groups. There was one death of unrelated cause within 30 days in the non-geriatric population and no deaths in the geriatric cohort. In an annual analysis, displayed in Fig. 2, frequency of discharge opioid prescriptions decreased in both the geriatric and non-geriatric cohorts prior to the limit. Median discharge MEDs for geriatric patients also decreased prior to the limit, from 225 in both years 2015 and 2016 to 90 in years 2017 and 2018.

Table 2.

Opioid Prescribing for Geriatric vs Non-Geriatric Patients.

| Geriatric (>65y.o) (n = 218) | Non-Geriatric (n = 670) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 76 (69–84) | 35 (26–49) | |

| Female | 120 (55.0%) | 233 (34.8%) | <0.001 |

| White | 171 (78.4%) | 368 (58.2%) | <0.001 |

| Admitted | 38 (17.4%) | 66 (9.9%) | 0.002 |

| Blunt Injury | 214 (98.2%) | 587 (87.6%) | <0.001 |

| Fall | 159 (72.9%) | 154 (23.0%) | <0.001 |

| Fall Hx | 64 (29.4%) | 19 (2.8%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Pain | 43 (19.7%) | 77 (11.5%) | 0.002 |

| DC Opioid Prescription | 58 (26.6%) | 235 (35.1%) | 0.025 |

| DCMEDs | 150 (98–300) | 113 (113–225) | 0.046 |

| DCMEDs Over 210 | 27 (46.6%) | 66 (28.1%) | 0.007 |

| DC Ancillary Pain Med | 61 (28.0%) | 334 (49.9%) | <0.001 |

| Any 30d Followup | 181 (83.0%) | 502 (75.6%) | 0.023 |

| Clinic Narcotics | 18 (15.3%) | 49 (18.8%) | 0.406 |

| Total Clinic MEDs | 225 (148–450) | 225 (150–450) | 0.705 |

DC: Discharge.

MEDs: Morphine Equivalent Dosage.

Values reported as percentages or medians with interquartile range.

Fig. 2.

Opioid prescription rates by year for geriatric and non-geriatric patients Discharge opioid prescription rates in %.

Vertical dashed line represents August 2017 introduction of opioid prescribing limit. Geriatric: Age ≥65.

Table 3 demonstrates the comparison of geriatric patients presenting with fall or having a fall history with geriatric patients who did not have a documented history of fall. Patients with fall risk were older (age 78 vs 70, p = 0.001), more often female (60% vs 38%, p = 0.006), and more often white (80% vs 69%, p = 0.010) but did not differ in medical or substance abuse history. Patients with fall risk did not differ in discharge opioid prescribing, median discharge MEDs, or percentage of prescriptions above the state limit of 210 MEDs. Follow-up needs, prescriptions, and dosages also did not differ between groups.

Table 3.

Prescribing in Geriatric Patients With and Without Fall and/or Fall History.

| FOFH (n = 168) | No FOFH (n = 50) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 78 (70–86) | 70 (67–76) | 0.001 |

| Female | 101 (60.1%) | 19 (38.0%) | 0.006 |

| White | 137 (80.1%) | 34 (69.4%) | 0.010 |

| Admitted | 28 (16.7%) | 10 (20.0%) | 0.585 |

| Blunt Injury | 168 (100%) | 46 (92.0%) | 0.003 |

| Chronic Pain | 36 (21.4%) | 7 (14.0%) | 0.247 |

| Psych History | 57 (33.9%) | 12 (24.0%) | 0.226 |

| Substance Abuse History | 24 (14.3%) | 6 (12.0%) | 0.680 |

| DC Opioid Prescription | 44 (26.2%) | 36 (28.0%) | 0.799 |

| DCMEDs | 154 (101–300) | 131 (90–319) | 0.874 |

| DCMEDs Over 210 | 21 (47.7%) | 6 (42.9%) | 0.75 |

| DC Ancillary Pain Meds | 42 (25.0%) | 19 (38.0%) | 0.072 |

| Any 30 Day Follow-up | 135 (80.4%) | 46 (92.0%) | 0.054 |

| Clinic Narcotics | 14 (15.4%) | 4 (15.2%) | 0.999 |

| Total Clinic MEDs | 150 (100–322) | 450 (250–550) | 0.294 |

FOFH: Fall or Fall History.

DC: Discharge.

MEDs: Morphine Equivalent Dosage.

Values reported as percentages or medians with interquartile range.

Discussion

Older patients comprise a rising share of trauma admissions, and are at high risk for iatrogenic harm after initial injury from excess administration of opioids. Providers must balance adequate analgesia with potential risks of opioids in this patient population, which include risk for persistent use similar to that of the general population as well as risk for falls and medication interactions. We have demonstrated that opioids are prescribed to geriatric patients less frequently and in lower doses than they were several years ago, prior to Ohio's opioid prescribing limit. While before-and-after comparisons of Ohio's opioid prescribing limit might suggest that it has been effective in curbing opioid prescribing, analysis of opioid prescribing by year indicates that physicians began to change prescribing behavior for geriatric trauma patients prior to the introduction of this limit. This is similar to the findings that we have reported previously for the general population.6 It is likely that physicians recognized the opioid epidemic through their own patient care and as future legislation was being discussed. While the limit focused primarily on the amount of opioids allowed to be prescribed, an awareness of the risks of opioid prescribing likely contributed to the reduction in number of prescriptions written as well. While several meetings and town hall discussions took place in our hospital, there was no formal protocol introduced for opioid prescribing during the study period.

A concern regarding decreased prescribing at hospital discharge is that patients will not have adequate analgesia to last through the first clinic follow-up, and that telephone calls, emergency department visits, and readmissions would increase. Our study did not demonstrate any increase in 30-day follow-up encounters or outpatient prescribing for geriatric patients.

While the successful reduction in opioid prescribing is laudable, our secondary analyses revealed that while opioids are prescribed less frequently to geriatric patients when compared to a non-geriatric cohort, the dose of opioid medications, when prescribed, was surprisingly higher than those prescriptions for non-geriatric patients, despite safety concerns such as fall risk, medication errors, and polypharmacy present in this population. Our study was not powered to detect a difference in risk factors that would explain the difference in doses seen, although we suspect that prior use of opioids in some patients may contribute to this effect.

Our results also suggest that physicians may not take into account a patient's fall history when prescribing opioids at discharge after minor injury. The presence of a historical fall or current presentation with a fall does not seem to influence prescribing behavior with geriatric patients with fall or fall history receiving discharge opioids at similar frequencies and quantities as their counterparts without those risk factors. This is of great concern given the association of opioid analgesics with falls in the geriatric population7-9 as well as the high morbidity and estimated 6% 30-day mortality associated with falls in the elderly.10 Our findings suggest there is significant room for improvement when tailoring opioid prescriptions to a patient's risk profile.

Trauma surgeons and emergency medicine physicians must undertake the difficult work of defining the typical analgesic requirements of patients with minor injuries and tracking their outcomes. Changing the culture of medicine to limit excessive prescribing will hopefully curb the effects of opioid dependence in the future. This is an area where collaboration between trauma systems could make a major impact on patient care, even with only short-term follow-up. In the meantime, we would suggest that physicians caring for minimally injured trauma patients, particularly the elderly, strongly consider whether opioid prescriptions are necessary for these patients, as well as the individual risk factors that these patients may have for opioid-related complications.

Limitations

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature and the quality of documentation in the medical record. Though every attempt was made to identify factors such as fall history and previous substance abuse, documentation is provider-dependent and level of detail may vary depending on a number of other factors. Due to the size of our geriatric sample and inability to record injury severity score for the majority of our patients, we were unable to adequately assess the effect of individual injury subtypes on opioid prescribing, but prior work at our institution demonstrated no significant change in injury type for the general population during the study period6. Additionally, while we are able to report prescribing behaviors, we do not have information on the opioid consumption of these patients; this would be the primary benefit of prospective research for this patient population and could potentially lead to more formal recommendations including specific opioid dosage. While our electronic medical record does include access to records at another major health system in our region, we were unable to assess prescriptions given by physicians who were outside of this network. Despite these limitations, we believe the findings of our study remain important, as opioid administration to older trauma patients is likely a blind spot in the efforts to curb the opioid epidemic.

Conclusions

Fewer discharge opioid prescriptions and lower dosages are given to minimally injured geriatric trauma patients now than were given several years ago. While this change happened in close proximity to an opioid prescribing limit, trauma surgeons and emergency medicine physicians appear to have reduced prescribing habits before the limit was imposed. While geriatric patients were prescribed opioids less frequently than younger patients, doses given were actually higher, despite safety concerns. Geriatric patients presenting with fall mechanism or having a history of falls received opioid prescriptions at similar frequencies and dosages compared to geriatric patients without either risk factor. Providers should carefully weigh safety concerns against appropriate pain control in geriatric trauma patients when prescribing opioids.

Acknowledgments

Sources of financial support

No external funding was received for this work.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors of this study have no relevant conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Davis CS, Lieberman AJ, Hernandez-Delgado H, Suba C. Laws limiting the prescribing or dispensing of opioids for acute pain in the United States: a national systematic legal review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;194:166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overton HN, Hanna MN, Bruhn WE, et al. Opioid-prescribing guidelines for common surgical procedures: an expert panel consensus. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227(4):411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a Parsells KJ, Cook SF, Kaufman DW, Anderson T, Rosenberg L, Mitchell AA. Prevalence and characteristics of opioid use in the US adult population. Pain. 2008;138:507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American geriatrics society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4): 674–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daoust R, Moore L, et al. Recent Opioid Use and Fall-related injury among older patients with trauma. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J). 2018;190(16):E500–E506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torchia MT, Munson J, Tosteson TD, et al. Patterns of opioid use in the 12 months following geriatric fragility fracture: a population based cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(3):298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zolin S, Ho V, Young B, et al. Opioid prescribing in minimally-injured trauma patients: effect of a state prescribing limit. J Surg. 2019. October;166(4):593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganz DA, Bao Y, Shekelle PG, Rubenstein LZ. Will my patient fall? J Am Med Assoc. 2007;297:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masud T, Morris RO. Epidemiology of falls. Age Ageing. 2001;30(Suppl 4):3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krebs EE, Paudel M, Taylor BC, et al. Association of opioids with falls, fractures, and physical performance among older men with persistent musculoskeletal pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):463–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siracuse JJ, Odell DD, Gondek SP, et al. Health Care and socioeconomic impact of falls in the elderly. Am J Surg. 2012;203:335–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]