Abstract

Background

The traditional Chinese medicine Cistanche deserticola has been reported to be valid for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. However, its active components for the protection of ischemic stroke are not clear. We aimed to explore the active components of C. deserticola against ischemic stroke as well as its potential mechanisms.

Methods

We investigated the brain protective effects of extracts from C. deserticola, total glycosides (TGs), polysaccharides (PSs), and oligosaccharides (OSs) in a rat model of middle cerebral artery occlusion-reperfusion (MCAO/R). 2, 3, 5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining was used to assess the cerebral infarction volume, and Evans blue assay was adopted to assess the blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability. Then, the expressions CD31, α-SMA, PDGFRβ, SYN, PSD95, MAP-2, ZO-1, claudin-5, occludin, Keap-1, and Nrf-2 were analyzed using western blotting or immunofluorescence, and the activities MDA, SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px were analyzed using kits.

Results

TGs treatment remarkably decreased neurological deficit scores and infarction volumes, promoted angiogenesis and neural remodeling, and effectively maintained blood-brain-barrier integrity compared with the model group. Furthermore, TGs significantly decreased MDA levels and increased antioxidant activities (SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px) in brains. Meanwhile, TGs remarkably downregulated Keap-1 expression and facilitated Nrf-2 nuclear translocation. On the contrary, no protective effects were observed for PSs and OSs groups.

Conclusion

TGs are the main active components of C. deserticola against MCAO/R-induced cerebral injury, and protection is mainly via the Nrf-2/Keap-1 pathway.

Keywords: Cistanche deserticola, cerebral injury, total glycosides, polysaccharides, oligosaccharides, Nrf-2/Keap-1 pathway

Introduction

Strokes are considered to be a major cause of death and disability in the world (Donnan et al., 2008). Nearly 87% of all stroke cases are triggered by ischemic stroke (Ovbiagele and Nguyen-Huynh, 2011). Currently, the most effective agent and the only FDA-approved drug used for ischemic stroke treatment is recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. However, a large amount of stroke patients fail to respond to this drug, owing to its narrow therapeutic time window and a serious risk of hemorrhagic complications (Lee et al., 2012; Schellinger and Kohrmann, 2014). A major challenge of thrombolytic treatment is ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, which is considered as a main cause of brain injury and function destruction. Reperfusion after cerebral ischemia increases the risk of brain hemorrhage, while leading to neurovascular injury and producing excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) which damage the blood-brain barrier (Alluri et al., 2015). A number of studies have confirmed that the disruption of the BBB is a major cause of the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke (Cao et al., 2016b).

The BBB consists mainly of endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes, neurons, and the basement membranes. The core components of the BBB are cerebral microvascular endothelial cells that are joined by tight junctions, thus restricting exogenous molecules into the brain. The pathological alterations of tight junctions—particularly occludin, claudin-5, and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1)—significantly affect the BBB function during an ischemic stroke, especially barrier permeability (Liu et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019). During I/R periods, excessive ROS is one of the main factors leading to the direct damage of brain neurons (Ding et al., 2014). ROS overproduction leads to the degradation of certain junctions and BBB disruption, which results in exogenous molecules entering into the brain through the BBB, leading to brain damage aggravation (Cheon et al., 2016; Zhang Q. Y. et al., 2017). Therefore, protection of the BBB by anti-oxidants has been regarded as a potential way to prevent reperfusion injury.

Besides the breakdown of the BBB, I/R can result in neurovascular injury and neuronal death (Jung et al., 2010). During a stroke, increased neuronal cell death may result from oxidative stress (Chi et al., 2018), and numerous studies have shown that ROS aggravates stroke severity and neurological damage (Kondo et al., 1997; Crack et al., 2001; Crack et al., 2006). Although clinical trials have not got satisfactory results, neuroprotection is still a promising strategy for treatment of acute ischemic stroke (Moretti et al., 2015). Thus, finding effective neuroprotection drugs to treat strokes is a benefit for stroke patients.

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) takes measures to intervene against the body's internal imbalance (Gaire, 2018). Owing to the complex pathogenesis of ischemic strokes, the multifactorial effect of TCM and their active constituents play a critical role in the treatment of strokes. Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma, widespread in arid or semi-arid areas throughout Mongolia and Northwest China, has been a widely used TCM herb for the treatment of various diseases such as forgetfulness and depression for more than 1,000 years in China. Modern pharmacological studies indicated that the crude extracts from C. deserticola showed multiple pharmacological activities, such as enhancing learning and memory function, neuroprotection, enhancing immunity, antioxidant, anti-aging, and antifatigue effects (Ko and Leung, 2007; Wang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015). Chemical analysis of C. deserticola showed that its main constitutes include phenylethanoid glycosides, iridoid glycosides, polysaccharides and oligosaccharides (Jiang and Tu, 2009). However, the active components of C. deserticola for brain protection are not very clear.

The neuroprotective property of C. deserticola implies its therapeutic potential in cognitive-related illness such as stroke and depression, as well as Alzheimer's disease (Wang et al., 2017). However, research on the impact of C. deserticola on strokes, including its active components and action mechanisms, is very limited. In the current work, we explored the protective effect of three extracts from C. deserticola, total glycosides (TGs, phenylethanoid glycosides, and other glycosides), polysaccharides (PSs), and oligosaccharides (OSs) on cerebral I/R injuries. Our findings may contribute to the accurate clinical application of C. deserticola and provide a candidate agent for ischemic stroke therapy.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

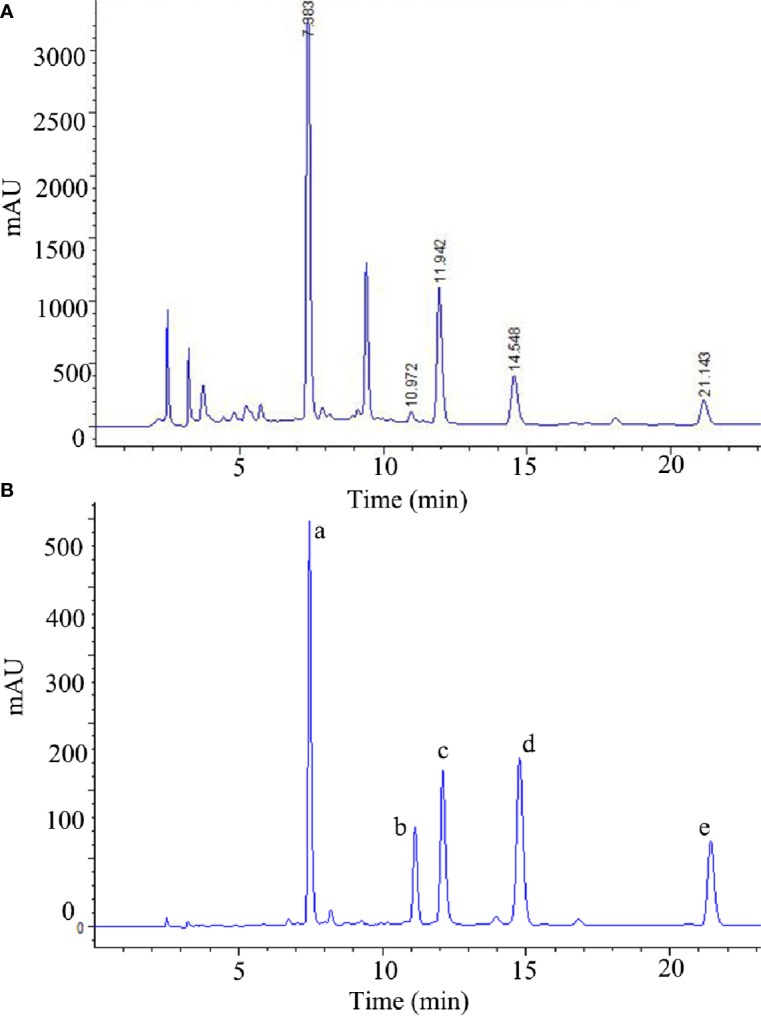

The stems of Cistanche deserticola were purchased from Alashan, Inner Mongolia, and identified by one of the authors (P.-F. Tu). TGs, PSs, and OSs were prepared according to our previously reported method (Gao et al., 2015). Quantitative analysis of TGs was performed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described (Li et al, 2019), and its chromatogram is shown in Figure 1 . The main components of TGs are echinacoside, tubuloside A, acteoside, isoacteoside, and 2'-acetylacteoside; their contents are 163.05 mg/g, 4.125 mg/g, 41.66 mg/g, 22.655 mg/g, and 12.045 mg/g, respectively. The contents of PSs and OSs are 69.42% and 65.24%, respectively, as determined by HPLC and the phenol–sulfuric acid analysis, respectively (Zhang A. et al., 2018; Shi et al, 2019).

Figure 1.

The HPLC chromatograms of the TGs (A) and standard references (B). (a) echinacoside, (b) tubuloside A, (c) acteoside, (d) isoacteoside, (e) 2'-acetylacteoside of TGs.

The standard references of echinacoside (A0282), tubuloside A (A0942), acteoside (A0280), isoacteoside (A0281), and 2'-acetylacteoside (A0943) were purchased from Chengdu Must Biotechnology (Sichuan, China). The purities of all standards are more than 98%. Nissl stain H&E kits were bought from Boster (Wuhan, China). Edaravone (T0407-1) was bought from Target Mol (Shanghai, China). Rabbit anti-rat MAP-2 (ab32454), Nrf-2 (ab31163), PDGFRβ (ab32570), Keap-1 (ab66620), and mouse anti-rat CD31 (ab24590) were purchased from Abcam Inc (Cambridge, MA, USA). Rabbit anti-rat Claudin5 (BS1069), ZO-1 (BS9802M), and Occludin (BS72035) were bought from Bioworld Technology (Nanjing, China). Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Boston, MA, USA) was the source of rabbit anti-rat Synapsin-1 (SYN,5297T), PSD95 (3450T), α-Smooth Muscle Actin (α-SMA,19245T). GAPDH (HRP-60004) was purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc. (Chicago, USA). Secondary antibodies were supplied by Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology (Beijing, China). Hoechst 33258 was obtained from Beyotime (Jiangsu, China).

Animals

Sprague-Dawley rats (male, weighing 250–300g) were obtained from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology (Beijing, China) and housed in an airconditioned room kept on a 12 h light/dark cycle. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the animal research ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010), and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking University Health Science Center (LA2019123).

Animal Experimental Protocols

The rats were subjected to MCAO/R, as previously described (Wang et al., 2018). Briefly, the left common carotid artery (CCA), external carotid artery (ECA), and internal carotid artery (ICA) were exposed, and a 3-0 nylon monofilament suture was inserted from the ECA into the ICA until reaching the middle cerebral artery (MCA). After 1.5 h of MCA occlusion, reperfusion was simulated by removing the filament. During the surgical procedure, the body temperature of all rats was maintained at 37.0°C.

Drug Administration

The rats were randomly separated into six groups using the SPSS software version 22.0 as described (Jiang et al., 2014): normal group (NOR); model group (MOD); edaeavone group (positive drug, 6 mL/kg, EDI); TGs group (280 mg/kg, TGs); PSs group (280 mg/kg, PSs), and OSs group (280 mg/kg, OSs). TGs, PSs, and OSs were administrated ig once a day after MCAO/R for 14 days. The NOR and MOD groups were treated with normal saline. The animal numbers are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Number of animals for different experimental groups and various parameters at 14 d after administration.

| Parameters | NOR | MOD | EDI | TGs | PSs | OSs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, mNSS | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 108 |

| TTC | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 48 |

| H&E,Nissl stain | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 30 |

| Immunofluorescent | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 30 |

| Total | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 216 |

Measurement of Weight and Modified Neurological Deficit Scores (mNSS)

Body weight was monitored on the 14th day using an ADVENTURE™ Digital Scale (OHAUS, New Jersey, USA). The mNSS was assessed according to the method described by FJ Wang (Wang et al., 2018), with minor revisions.

2, 3, 5-Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride (TTC) Staining

Infarct volume was measured as described previously (Wang et al., 2015). In brief, the brains were sectioned into seven equally spaced coronal blocks (2 mm). These sections were stained with 2% TTC (Coolaber, Beijing, China) at 37°C for 15 min. Infarct volume (%) = (ipsilateral ischemic hemisphere volume−contralateral ischemic hemisphere volume)/contralateral ischemic hemisphere volume × 100.

Nissl and H&E Staining

The rats were deeply anesthetized, and the whole brain was then rapidly removed from the skull and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned into slice of 7 µm thickness. The sections were stained with Nissl and H&E. In this study, six random 200 × 200 µm fields were captured in each tissue specimen with a light microscope. The number of Nissl's bodies was counted with IPP software version 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, USA).

Evans Blue Assay

Rats were injected with 2% EB (Coolaber Science & Technology Co., LTD) after MCAO/R. Two hours later, the rats were anesthetized and the whole brain was then rapidly removed and homogenized in acetone. The supernatants were analyzed at 620 nm by an 800 TS absorbance reader (BioTek, USA).

Measurement of the Activities of Catalase (CAT), Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Malondialdehyde (MDA), and Glutathione Peroxidase (GSH-Px)

All serum samples were centrifuged at 4,000 × rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and then analyzed to detect the activities of MDA, CAT, SOD, and GSH-Px following the manufacturer's instructions (Jiangsu Meimian industrial Co., Ltd, China).

Western Blotting Analysis

Brain tissues (100 mg) collected from each rat were homogenized and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer, and then analyzed to detect the protein concentration using a BCA kit (Beijing TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.). Tissue total proteins were loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked using 5% skim milk, then incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C. The membrane was then incubated with a secondary antibody. Western blot analysis was analyzed using Kodak Digital Imaging System (5200 Multi, Tanon, China).

Immunofluorescent Analysis

Immunofluorescence staining for CD31, α-SMA, ZO-1, claudin5, occludin, PDGFRβ, SYN, PSD95, MAP-2, Nrf-2 and Keap-1 were performed. Primary antibodies against Nrf-2, CD31, α-SMA, ZO-1, claudin5, occludin, PDGFRβ, SYN, PSD95, MAP-2 and Keap-1 were diluted to 1:200 and 1:100, respectively. The secondary antibodys of Alexa Flur 488 mouse anti-rabbit IgG and rhodamine (TRITC) goat anti-rabbit IgG were both diluted to 1:200. The nucleuses were stained by Hoechst 33258. Images were captured using Vectra® Polaris™ Automated Quantitative Pathology Imaging System (PerkinElmer, USA). The protein expression was analyzed using IPP software version 6.0.

Statistical Analysis

All data were described as mean ± SD. SPSS software version 22.0 was performed for statistical analysis. One-way ANOVA was used when comparing different groups. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistical difference.

Results

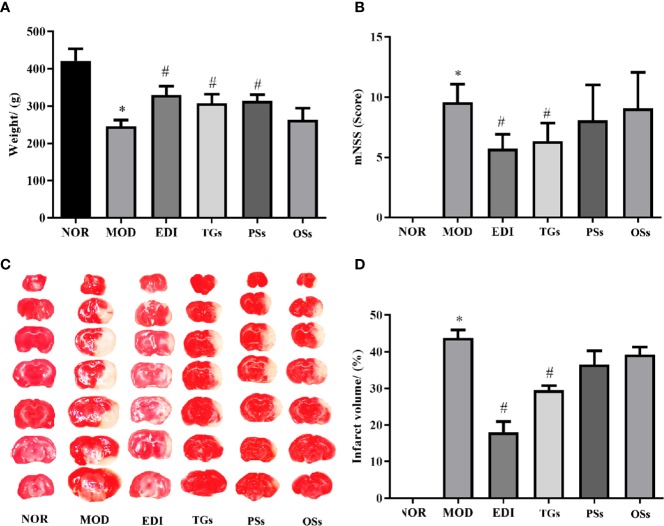

TGs Increase Body Weight and Reduces Brain Damages in MCAO/R Rats

After 14 days of cure with TGs, PSs, Oss, and EDI, the body weights, neurological deficits and infarct volumes of I/R rats were evaluated. The results showed that the body weights in the MOD group were greatly decreased, while the decreased weights in TGs, PSs and EDI groups were obviously increased ( Figure 2A ). Neurological deficit scores were substantially lowered by EDI and TGs ( Figure 2B ). The brain slices in NOR group rats were deep red and there were no infarctions, while the rats of the MOD group showed a large ipsilateral cerebral infarction. After TGs treatment, the infarct volumes were significantly reduced ( Figures 2C, D ). The PSs and OSs treatment showed no obvious effect on the above indexes. The above data showed that TGs could markedly alleviate the I/R-induced cerebral injury, but PSs and OSs could not.

Figure 2.

TGs reduce the brain damage induced by transient focal cerebral ischemia. (A) TGs increase weight in the MCAO/R rats. (B) TGs decrease neurological deficit scores at 14 d post-MCAO/R. (C, D) Representative photographs of TTC-stained coronal brain sections show viable (red) and dead (white) tissues; TTC staining shows that the cerebral infarction areas in the TGs group are significantly smaller than those in the model group. *P < 0.05 vs NOR. # P < 0.05 vs MOD.

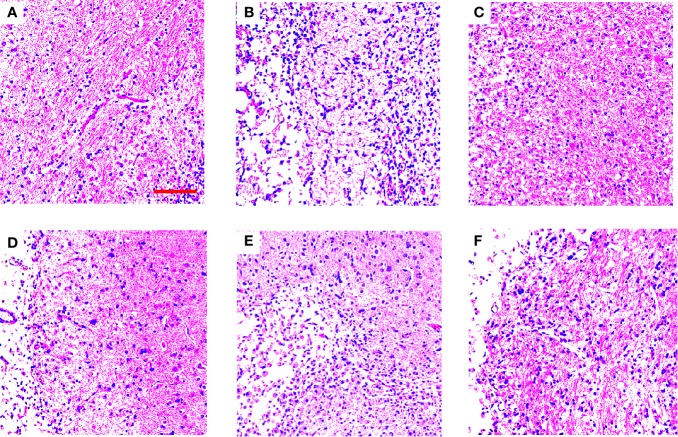

TGs Ameliorate Histopathological Damage in MCAO/R Rats

In order to determine some of the effects of TGs, PSs, and OSs treatment on histopathological damages, H&E staining was done to reveal pathological damage. The histomorphological structures of brains in the NOR group were arranged regularly. The morphology changes in the TGs groups were slighter than those in the MOD group. However, the PSs and OSs treatment groups showed no significant amelioration of the morphology changes ( Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

TGs ameliorate histopathological damage in MCAO/R rats. HE staining of coronal sections in the penumbra of ischemic areas of NOR, MOD, EDI, TGs, PSs, and OSs groups at 14 d after I/R. The cell morphology in the MOD group is shrinkage, nuclear pyknosis, and vacuolization, while the cells in the TGs group are relatively normal and show less damage, compared with those in the MOD group. (A–F) are NOR, MOD, EDI, TGs, PSs, and OSs groups, respectively. Scale bar = 100 µm.

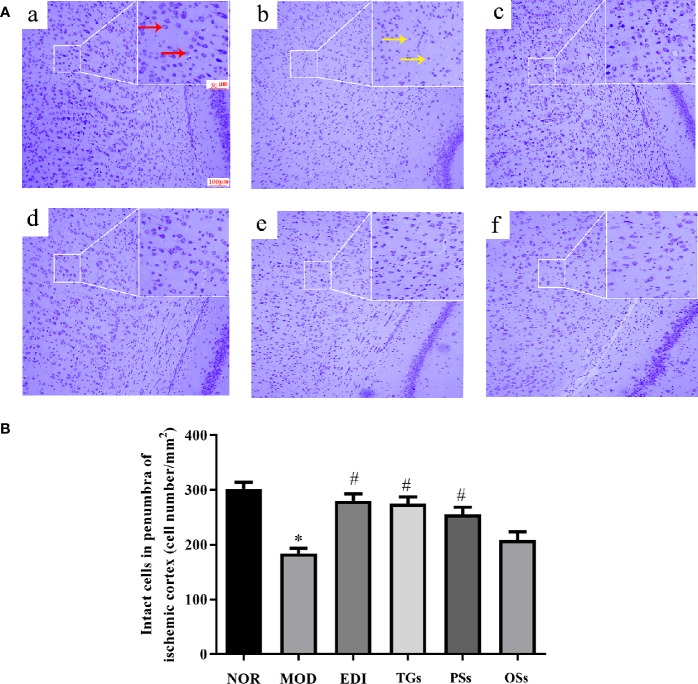

TGs Attenuate Neuronal Injury After I/R-Induced Rats

Nissl staining showed the histopathological changes of neurons in the penumbra of ischemic area. As shown in Figure 4 , the normal neurons had a clear nucleolus and intact structure. In the MOD group, the neurons had enlarged intercellular spaces. The nissl bodies were disappeared, shrunken and deep stained. However, these changes were rarely observed in the EDI, TGs, and PSs groups. These results illustrated that TGs and PSs could significantly attenuate ischemia/reperfusion-induced neuronal injury.

Figure 4.

TGs attenuate neuronal injury after I/R-treated rats. (A) Nissl staining in the penumbra of ischemic area of I/R rats. Normal neurons have normal morphology with clear nucleolus, abundant cytoplasm, and intact structure (red arrow). Abnormal neurons are shrunken and deep stained (yellow arrow), while a greater increase of intact cells is evident in the TGs group compared with the MOD group. a–f are NOR, MOD, EDI, TGs, PSs and OSs groups, respectively. (B) Quantitative analysis of intact cells in penumbra of ischemic area at 14 days after treatment. *P < 0.05 vs NOR, # P < 0.05 vs MOD.

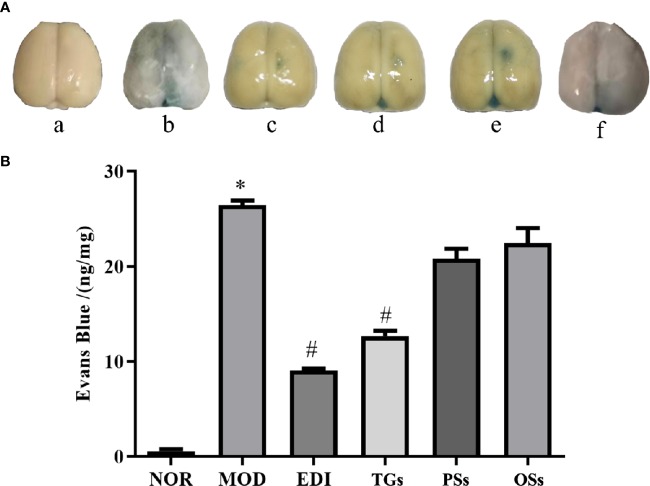

TGs Attenuate BBB Disruption After I/R-Treated Rats

Evans blue assay is a classical method for researching the change of BBB permeability. The experiment results showed that increased Evans blue was observed in the MOD group, while there was significantly decreased Evans blue in the TGs and EDI treated rats. Moreover, there was no significant difference between PSs and OSs therapy groups ( Figure 5 ). These results suggested that TGs could significantly attenuate BBB disruption.

Figure 5.

TGs attenuate BBB disruption after I/R injury. (A) Representative pictures of Evans blue extravasation. a–f are NOR, MOD, EDI, TGs, PSs, and OSs groups, respectively. (B) Quantitative analysis of Evans blue extravasation from brain extracts at 14 days after treatment. *P < 0.05 vs NOR, # P < 0.05 vs MOD.

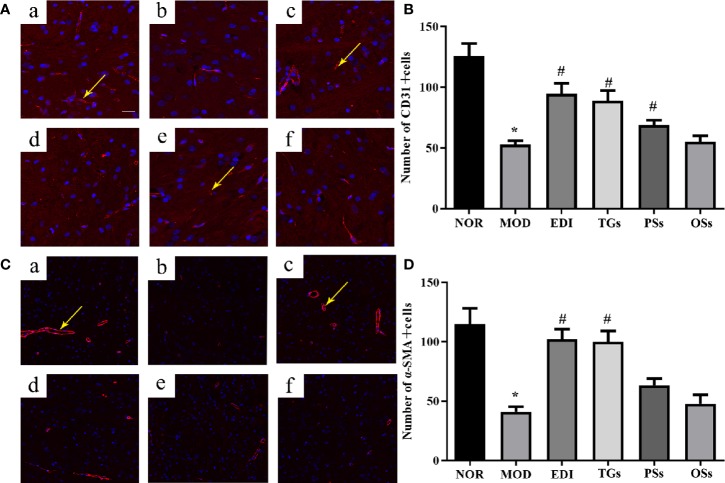

TGs Promote Angiogenesis in I/R Injured Rats

More recent studies show that angiogenesis plays a critical role in neurological functional recovery and prognostic outcome after acute ischemic stroke (Yuen et al., 2015). To evaluate effects of TGs, PSs, and OSs on angiogenesis, the CD31 and α-SMA were used to quantify the capillary numbers. Immunofluorescence staining showed that the MOD group caused a remarkable decrease in the expressions of CD31 ( Figures 6A, B ) and α-SMA ( Figures 6C, D ) in the penumbra of ischemic areas of I/R rats, in comparison with the normal rats. This result illustrated that I/R could cause the vascular damage in the cortex penumbra of ischemic hemispheres. However, the TGs and EDI treatment remarkably increased capillary density, angiogenesis, and arteriogenesis as indicated by increased expressions of CD31 and α-SMA. These results suggest that TGs could promote angiogenesis in the ischemic penumbra of I/R rats, but the PSs and OSs could not.

Figure 6.

TGs promote neovascularization in rats with cerebral I/R. Representative images obtained from the cortex penumbra of ischemic hemispheres. (A, C) Representative immunofluorescence images of CD31 and α-SMA in the I/R rats after treatment with TGs, PSs and OSs for 14 days, respectively. a–f are NOR, MOD, EDI, TGs, PSs, and OSs groups, respectively. (B, D) The bar graphs show the analysis of positive immunostaining of CD31 and α-SAM in the I/R rats at 14 days after treatment. *P < 0.05 vs NOR, # P < 0.05 vs MOD. Scale bar in all panels = 100 μm.

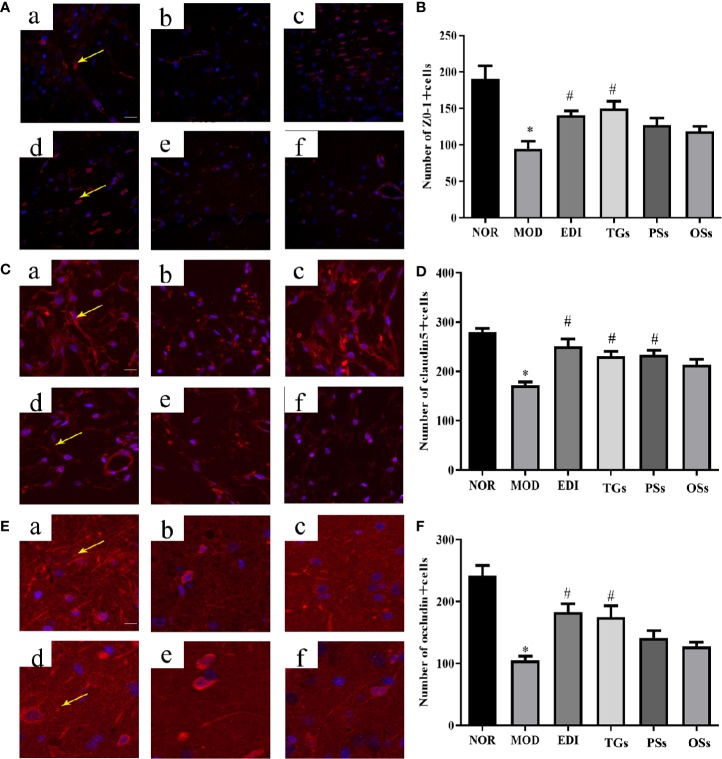

TGs Increase Expression of Tight Junction Proteins in I/R Injured Rats

BBB disruption can elevate brain water content and tissue swelling, leading to brain injury. Tight junction proteins are important structural components of the BBB (Tenreiro et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2018). To test whether TGs, PSs, and OSs treatment after stroke might influence BBB integrity, the expressions of ZO-1, claudin-5, and occludin were performed by immunofluorescence analysis. The results indicated that the expressions of claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1 were visibly decreased in the MOD group. However, they were substantially increased after 14 days of TGs administration. PSs and OSs groups showed no significant changes in these protein expressions ( Figure 7 ). These data indicated that the TGs can regulate tight junction protein expressions and probably maintain BBB integrity after I/R injury.

Figure 7.

TGs increase expression of tight junction proteins in MCAO/R rats. Representative images obtained from the cortex penumbra of ischemic hemispheres. (A, C, E) Protein expression levels of ZO-1, claudin5, and occludin were measured by immunofluorescence, respectively. (B, D, F) Statistical analysis of the numbers of ZO-1, claudin5, and occludin positive cells, respectively. a–f are NOR, MOD, EDI, TGs, PSs and OSs groups, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs NOR, # P < 0.05 vs MOD. Scale bar = 50 μm.

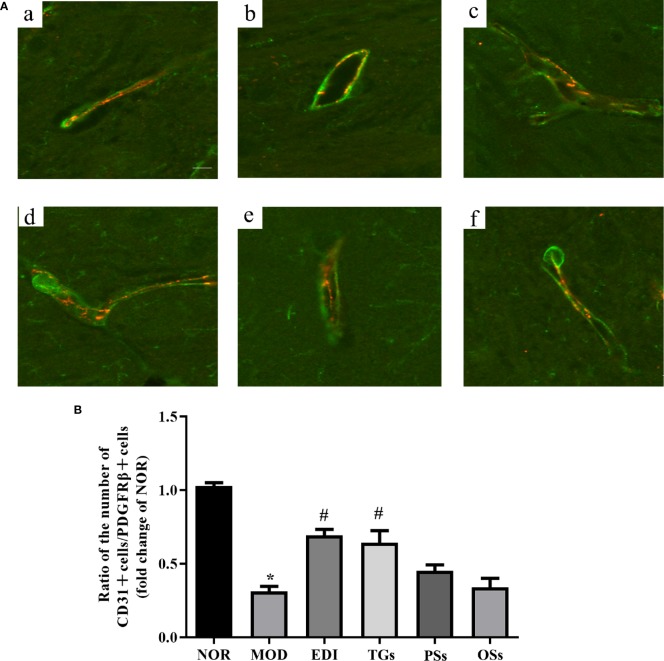

TGs Increase Pericyte Coverage on Capillaries in I/R Injured Rats

Pericyte coverage on capillaries plays a critical role in maintaining BBB integrity (Armulik et al., 2010; Daneman et al., 2010). Thus, we tested whether pericyte coverage could be increased by TGs, PSs, and OSs treatment. Immunofluorescence intensity analysis results showed that both PDGFRβ and CD31 expressions were dramatically decreased in the MOD group. Administration of TGs to the I/R rats significantly recovered or even increased the expression intensities of the PDGFRβ and CD31, but no difference was observed in the PSs and OSs treatment groups ( Figure 8 ). Thus, treatment of TGs could significantly increase pericyte coverage. These findings further confirmed that TGs can maintain the integrity of BBB after I/R.

Figure 8.

TGs increases pericyte coverage on capillaries in I/R injury rats. Representative images obtained from the ischemic penumbra of cortex. (A) Representative immunofluorescence images of PDGFRβ (green) and CD31 (red) staining in the MCAO/R rats at 14 days after TGs, PSs and OSs treatment. a–f are NOR, MOD, EDI, TGs, PSs and OSs groups, respectively. (B) Ratio of CD31-positive cell numbers to the PDGFRβ-positive cell numbers in each tissue. *P < 0.05 vs NOR, # P < 0.05 vs MOD. Scale bar in all panels = 20 μm.

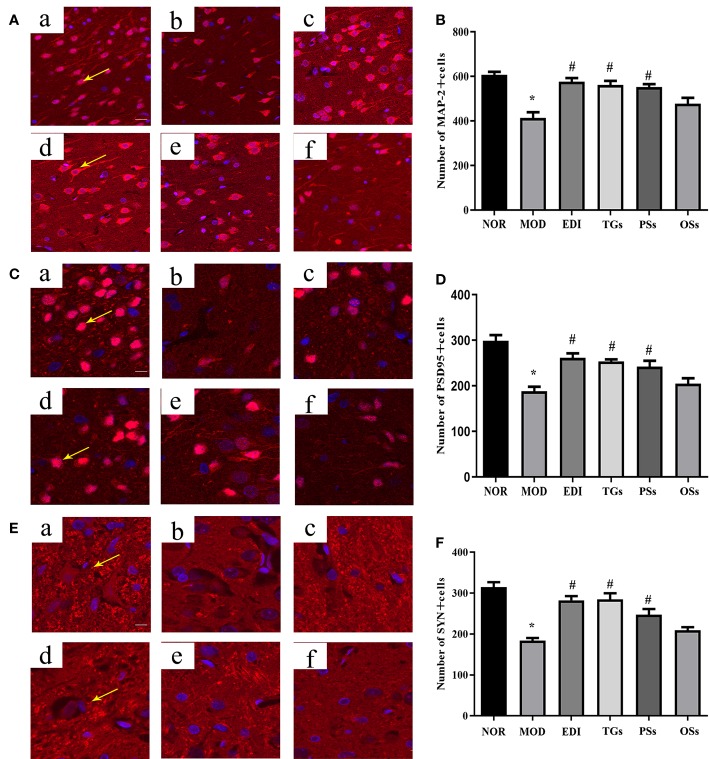

TGs Promote Neural Remodeling in I/R Injured Rats

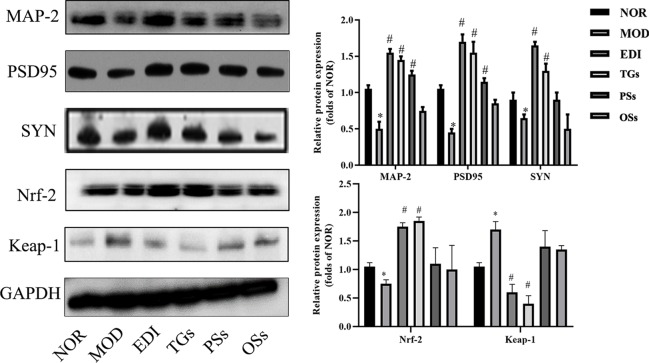

According to numerous studies, neurogenesis after a stroke can significantly improve functional recovery (Grefkes and Ward, 2014; Zhang et al., 2019). Synaptophysin (SYN), postsynaptic density 95 (PSD-95) proteins and microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) were used as markers to examine neuronal plasticity in the ischemic penumbra of the cortex. In order to assess the effects of TGs, PSs, and OSs treatment on neurogenesis in I/R injured rats, the immunofluorescence and western blot for SYN, PSD95 and MAP-2 expressions were performed. As shown in Figures 9 and 10 , the SYN, PSD95 and MAP-2 expression levels in I/R rats after 14 days reperfusion decreased in comparison with the NOR rats, while the TGs and PSs cure could significantly up-regulate their expression levels. The OSs group had no significant change compared with the MOD group. The data indicated that the TGs and PSs cure was able to dramatically promote neural remodeling after I/R injury.

Figure 9.

TGs promote neural remodeling in I/R injury rats. Representative images obtained from the cortex penumbra of ischemic hemispheres. (A, C, E) Representative immunofluorescence images of MAP-2, PSD95 and SYN in the MCAO/R rats at 14 days after TGs, PSs and OSs treatment. (B, D, F) Statistical analysis of the numbers of MAP-2, PSD95 and SYN positive cells, respectively. a–f are NOR, MOD, EDI, TGs, PSs and OSs groups, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs NOR, # P < 0.05 vs MOD. Scale bar in all panels = 50 μm.

Figure 10.

TGs promote the expressions of MAP-2, PSD95, SYN and Nrf-2 and reduce the expression of Keap-1 in I/R-treated rats. *P < 0.05 vs NOR, # P < 0.05 vs MOD.

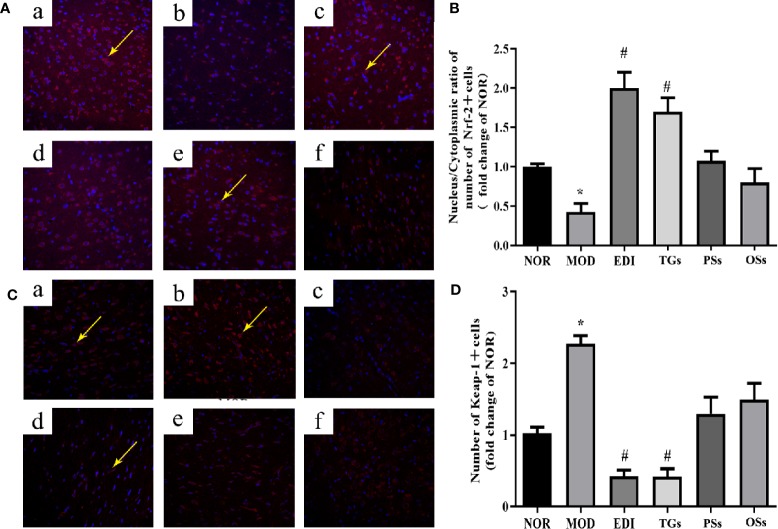

TGs Alter Nrf-2 and Keap-1 Expressions in I/R Injured Rats

Oxidative stress is a main pathogenic mechanism in I/R injury (Ya et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018). The studies verified that Nrf-2 is a master regulator of antioxidative responses (Thompson et al., 2015). To investigate Nrf-2 and Keap-1 mediated oxidative responses after I/R injury, we evaluated the cytoplasmic expression as well as nuclear translocation of Keap-1. Meanwhile, the expression of Nrf-2 in I/R injured rats brain tissues was also assayed ( Figures 10 and 11 ). According to the immunofluorescence analysis, Nrf-2 was found to be mainly located at the cytoplasm in the NOR group. In the TGs group, the expression of Nrf-2 in cytoplasmic localization was downregulated, but upregulated in the nucleus, and a decreased Keap-1 expression was also observed. The data showed that the brain protection of TGs could be associated with the modulation of Nrf-2 and Keap-1.

Figure 11.

TGs significantly decrease the expression of Keap-1 and facilitate the nuclear translocation of Nrf-2. Representative images obtained from the cortex penumbraof ischemic hemispheres. (A) Keap-1 dependent Nrf-2 nuclear translocation was observed in I/R rats brain tissue. (C) Keap1 degradation after TGs treatment to I/R rats braintissue. The analysis was carried out using immunofluorescence staining. af are NOR, MOD, EDI, TGs, PSs and OSs groups, respectively. (B, D) Bar graphs show aquantification of the nucleus/cytoplasmic ratio of Nrf-2 and the expression of Keap-1. *P < 0.05 vs NOR, # P < 0.05 vs MOD. Scale bar = 100 mm.

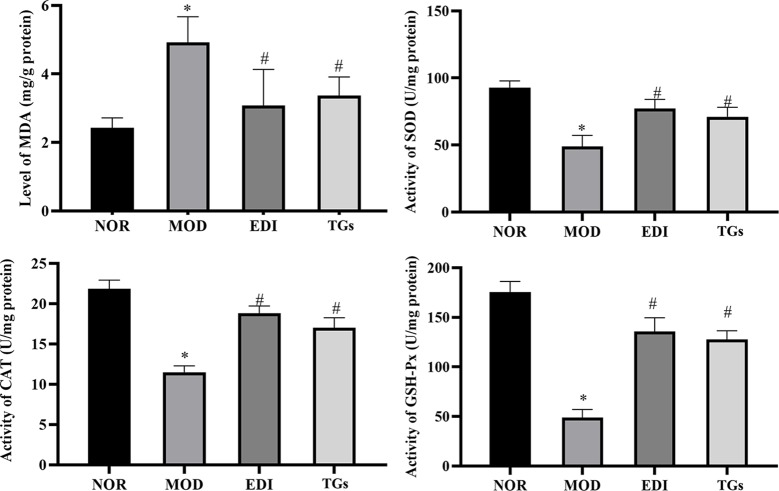

TGs Attenuate Brain Tissue Oxidative Stress in I/R Injured Rats

In order to confirm the antioxidative effects of TGs, the activities of SOD, CAT, GSH-Px and MDA were evaluated in I/R injured rats. In Figure 12 , the content of MDA was markedly increased in the MOD group, and at the same time the activities of SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px were decreased, compared to the normal rats. Conversely, TGs treatment led to a significant decrease in the content of MDA and increase in the activities of SOD, CAT and GSH-Px. These results further confirmed the antioxidation activity of TGs.

Figure 12.

TGs elevate the levels of SOD, CAT and GSH-Px and reduces the level of MDA in I/R-treated rats. The content of MDA increases in the brain tissue after I/Rinjury, along with the activities of SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px decrease. TGs treatment reverses these injury-induced changes. *P < 0.05 vs NOR, # P < 0.05 vs MOD.

Discussion

Many studies suggest that the TCM C. deserticola has extensive biological activities, e.g. enhancing the ability to learn, memory, and immunity (Dong et al., 2007; Jiang and Tu, 2009; Wang et al., 2017; Xia et al., 2018). However, the active components of C. deserticola for neuroprotection remain unclear. The current work aims to screen the active components from C. deserticola against ischemic stroke on the MCAO/R model. Three extracts from C. deserticola (TGs, PSs, and OSs) were used to evaluate their effects on MCAO/R rats, as well as possible mechanisms.

Stroke is a common acute cerebrovascular disease. Epidemiological studies show that stroke is more common in men than in women (Sealy-Jefferson et al., 2012; Guzik and Bushnell, 2017). Thus, in our experiment, male rats were adopted for the tests. Our results proved that I/R induction accelerated oxidative stress and infarct volume, breaking the BBB and leading to nerve and cerebrovascular injury. After screening, TGs were found to decrease infarct volume and promote neural remodeling and angiogenesis. Moreover, TGs were observed to maintain BBB integrity after I/R injury. On the contrary, PSs and OSs bring no significant alleviation to I/R injury. Thus, TGs are considered the major active fraction of C. deserticola for neuroprotection, potentially through promoting neural remodeling, angiogenesis and BBB integrity via activating Nrf-2/Keap-1 pathway.

Mounting evidence indicates that establishment of effective collateral circulation is significantly important for avoiding the formation of infarction and ischemic penumbra, and is a critical treatment at an early stage of ischemic stroke (ElAli, 2016; Iwasawa et al., 2016). The proliferation of vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells after ischemic infarction determines the establishment of collateral circulation. However, the ischemia models have a common phenomenon—that is, oxidative stress widely existed in the brain microvasculature. Study data have displayed that a large number of antioxidants can disturb the function of the BBB and the properties of angiogenesis (Mentor and Fisher, 2017). CD31 and α-SMA are the markers of vascular endothelial cells as well as smooth muscle cells, respectively (Saboor et al., 2016). To investigate the effect on the above-mentioned cell proliferation of the extracts from C. deserticola, we examined the expressions of CD31 and α-SMA in the cerebral ischemic penumbra homogenate. Our data showed that TGs strikingly enhanced the expressions of CD31 and α-SMA. However, there was no significant differences for PSs and OSs groups. Therefore, we deduced that TGs may reduce brain damage by promoting angiogenesis via increasing the expressions of CD31 and α-SMA, whereas PSs and OSs provided no such protection from brain damage. These results further confirmed that only TGs could prevent cerebral I/R injury.

Ischemic stroke can be thought as the result of cerebral ischemia caused by impairment in the neuronal plasticity or remodeling of brain areas. The majority of stroke patients suffer neurological deficits. Activating neurogenesis is a promising strategy for stroke patients to improve their neurological functions (Cramer and Chopp, 2000). Neurogenesis directly participates in neurological function recovery after brain I/R injury (Zhang et al., 2019). Previous research shows that TGs can improve the survival rate of hippocampal pyramidal cells and induce neurogenesis (Lian et al., 2017). Oxidative stress causes the loss of neurons during lots of diseases, such as Parkinson, stroke, and so on (Duan and Si, 2019; Singh et al., 2019). Nrf-2 transcribes lots of genes related to neuro-protection in their promoter region, mainly including SOD, MDA, CAT, and γ-glutamyl cysteine ligases, etc (Satoh et al., 2006). SYN, PSD-95, and MAP-2 proteins, which are associated closely with synaptic formation and neurotransmission, can be considered as markers of research neuronal plasticity in the ischemic penumbra region. After studying, we found that the cure with TGs could significantly increase the expressions of PSD95, SYN, and MAP-2, indicating that the cerebral protection of TGs was correlated with the enhanced neuronal plasticity during I/R. However, it's a pity that there is no obvious difference for PSs as well as OSs groups. These results indicated that TGs could enhance neuroplasticity after cerebral I/R injury.

Imaging research into stroke patients showed that BBB dysfunction can be thought as a striking attribute of the peri-ischemic brain (Bang et al., 2007). The TJs, which are composed of cytoplasmic proteins, transmembrane proteins, and junction adhesion molecules between capillary endothelial cells, are very important in maintaining BBB integrity (Ye et al., 2019). Among them, ZO-1, claudin-5, and occludin are the most important proteins in TJs. Mounting evidence indicates that the increased permeability of BBB induced by ischemia generally correlates with the alterations of ZO-1, claudin-5, and occludin (Cao et al., 2016a; Page et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018). In this work, the results demonstrated that although TGs could significantly increase the expressions of ZO-1, claudin-5, and occludin proteins in MCAO-induced brain tissues, neither PSs nor OSs did. The BBB consists of cerebral endothelial cells and is closely associated with pericytes (Nyul-Toth et al., 2016). Pericytes are vital to BBB integrity (Bell et al., 2010). Ischemic stroke triggers pericytes death and detachment from brain endothelial cells in the acute phase, thus destabilizing the microvasculature and altering BBB properties (Zechariah et al., 2013). Our data showed that TGs could increase pericyte coverage on capillaries and increase the expression levels of ZO-1, claudin-5 and occludin. These phenomena proved that TGs could effectively protect BBB integrity after cerebral I/R injury. In summary, TGs may attenuate cerebral injury in multiple ways, such as promoting angiogenesis, improving neuronal plasticity, and maintaining the integrity of the BBB.

We then investigated the signaling pathway to explore the mechanism underlying the TGs brain protection. The process of I/R injury is multifactorial, and thus numerous mechanisms are involved in the pathogenesis. Oxidative stress is a fundamental risk factor contributing to I/R-induced brain injury (Suda et al., 2013), such as BBB structure damage, vascular endothelial dysfunction, and aggravation of ischemic neuronal injury (Xiong et al., 2015; Caglayan et al., 2019; Priestley et al., 2019). Thus, oxidative stress has become an attractive therapeutic target in I/R-induced brain injury. Phase 2 enzymes, which are mediated by nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf-2), have been considered as an important means by which neurons protect themselves against oxidative stress (Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2015; Ya et al., 2018). Mounting evidences indicate that activation of Nrf-2 during I/R is a potential therapeutic target for neuroprotection (Ding et al., 2015; Zhang R. et al., 2017). Nrf-2, as an important regulator of endogenous antioxidant defense, mediates the level of heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) and other antioxidant enzymes, such as NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), SOD, CAT, GSH, and MDA (Siow et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2014). Moreover, Nrf-2 plays an important regulator role in angiogenesis. The present study shows that Nrf-2 can be significantly enhanced and activated in the process of vascular development (Wei et al., 2013).

As previously described (Jiang and Tu, 2009), TGs contain lots of bioactive compounds, for example echinacoside, tubuloside A, acteoside, isoacteoside and 2'-acetylacteoside, and some of them showed neuroprotective functions after cerebral I/R injury (Peng et al., 2016). Echinacoside has lots of pharmacological effects, such as antioxidation, anti-senescence, neuroprotection, anti-inflammation, promotion of cicatrization, hepatoprotection, promotion of bone formation and anti-tumor activities (Yu et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Zhang Y. et al., 2018; Ji et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019). Recently, echinacoside has been identified as a potent antioxidant in the central nervous system (Lu et al., 2016). Echinacoside can cut down MDA content and improve the activities of SOD and GSH-Px in ischemia brain injury, and molecular docking analysis displayed that echinacoside may bind to Keap-1, leading to the Nrf-2 nuclear translocation (Li et al., 2018). The study of Xia showed that acteoside could decrease the infarct volume and brain water content to improve neurological deficits in MCAO/R rats through mitigating oxidative stress (Xia et al., 2018). Other studies have demonstrated that isoacteoside could increase the activities of cellular antioxidant enzymes, SOD and CAT in H2O2-treated V79-4 cells (Chae et al., 2005). Based on the above reports of the active compounds contained in TGs, it is possible to deduce that TGs could protect against ischemic stroke via the antioxidation pathways.

Li reported on the neuroprotective effects of phenylethanoid glycosides (PhGs) on H2O2-induced apoptosis on PC12 cells via the Nrf2/ARE pathway (Li et al., 2018). These PhGs significantly suppressed by triggering Nrf2 nuclear translocation and increasing expressions of HO-1, NQO1, glutamate cysteine ligase-catalytic subunit (GCLC), and glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLM) (Li et al., 2018; Gong et al., 2019). Therefore, these findings suggest that the Nrf-2/ARE pathway plays a crucial role in PhGs-mediated protective effects on neuronal cells. Similarly, in this study, we found that TGs could decrease the level of MDA and increase the levels of SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px in the I/R rats. Meanwhile, TGs could upregulate the Nrf2 expression in the nucleus, downregulate the corresponding expression in the cytoplasm, and significantly decrease the Keap-1 expression. Therefore, the Nrf-2/Keap-1 pathway may be involved in TGs-mediated neuroprotective effects. Further validation of this pathway would be performed in vitro cell culture with oxygen-glucose deprivation/reoxygenation injury models in the future. Moreover, C. deserticola extracts were administrated in our study for 14 days continuously. Since adult neurogenesis would affect the interpretation of neuroprotective effects during 14 days reperfusion, neurogenesis cannot be excluded in our current experiment design in exploring the neuroprotective effect of CTs. This is the limitation of our research.

In conclusion, it is the TGs from C. deserticola that can enhance angiogenesis and neurogenesis as well as maintain the integrity of the BBB in I/R injury rats, but not the PSs and OSs. The effects could be mediated by the activation of the Nrf-2/Keap-1 pathway.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

This work was carried out according to the Guidelines for Animal Experiments of Peking University. The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Peking University Health Science Center (LA2019123).

Author Contributions

YJ, KZ, and PT designed the research. FW performed the research. FW and RL analyzed the data. FW, RL, and JC wrote the manuscript and HPLC analysis. JC, KZ, YJ, and PT revised the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project (2017YFC1702400, 2019YFC1711000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773932), and the National Key Technology R&D Program “New Drug Innovation” of China (2018ZX09711001-008-003).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor declared a shared affiliation, though no other collaboration, with the authors KZ, YJ, at time of review.

References

- Alluri H., Anasooya Shaji C., Davis M. L., Tharakan B. (2015). Oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation as an in vitro ischemia-reperfusion injury model for studying blood-brain barrier dysfunction. J. Vis. Exp. 99, e52699. 10.3791/52699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armulik A., Genove G., Mae M., Nisancioglu M. H., Wallgard E., Niaudet C., et al. (2010). Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature 468 (7323), 557–561. 10.1038/nature09522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang O. Y., Buck B. H., Saver J. L., Alger J. R., Yoon S. R., Starkman S., et al. (2007). Prediction of hemorrhagic transformation after recanalization therapy using T2*-permeability magnetic resonance imaging. Ann. Neurol. 62 (2), 170–176. 10.1002/ana.21174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell R. D., Winkler E. A., Sagare A. P., Singh I., LaRue B., Deane R., et al. (2010). Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 68 (3), 409–427. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caglayan B., Kilic E., Dalay A., Altunay S., Tuzcu M., Erten F., et al. (2019). Allyl isothiocyanate attenuates oxidative stress and inflammation by modulating Nrf2/HO-1 and NF-kappaB pathways in traumatic brain injury in mice. Mol. Biol. Rep. 46 (1), 241–250. 10.1007/s11033-018-4465-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G., Jiang N., Hu Y., Zhang Y., Wang G., Yin M., et al. (2016. a). Ruscogenin attenuates cerebral ischemia-induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction by suppressing TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation and the MAPK pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 (9), 1–17. 10.3390/ijms17091418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G., Ye X., Xu Y., Yin M., Chen H., Kou J., et al. (2016. b). YiQiFuMai powder injection ameliorates blood-brain barrier dysfunction and brain edema after focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 10, 315–325. 10.2147/dddt.S96818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae S., Kim J. S., Kang K. A., Bu H. D., Lee Y., Seo Y. R., et al. (2005). Antioxidant activity of isoacteoside from Clerodendron trichotomum . J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 68 (5), 389–400. 10.1080/15287390590900750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon S. Y., Cho K. J., Kim S. Y., Kam E. H., Lee J. E., Koo B. N. (2016). Blockade of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 attenuates matrix metalloproteinase 9 activity in brain endothelial cells and the subsequent apoptosis in neurons after ischemic injury. Front. Cell Neurosci. 10, 213. 10.3389/fncel.2016.00213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H., Chang H. Y., Sang T. K. (2018). Neuronal cell death mechanisms in major neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (10), 1–18. 10.3390/ijms19103082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack P. J., Taylor J. M., Flentjar N. J., de Haan J., Hertzog P., Iannello R. C., et al. (2001). Increased infarct size and exacerbated apoptosis in the glutathione peroxidase-1 (Gpx-1) knockout mouse brain in response to ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Neurochem. 78 (6), 1389–1399. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00535.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack P. J., Taylor J. M., Ali U., Mansell A., Hertzog P. J. (2006). Potential contribution of NF-kappaB in neuronal cell death in the glutathione peroxidase-1 knockout mouse in response to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Stroke 37 (6), 1533–1538. 10.1161/01.Str.0000221708.17159.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer S. C., Chopp M. (2000). Recovery recapitulates ontogeny. Trends Neurosci. 23 (6), 265–271. 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01562-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneman R., Zhou L., Kebede A. A., Barres B. A. (2010). Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature 468 (7323), 562–566. 10.1038/nature09513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Chen M., Wang M., Wang M., Zhang T., Park J., et al. (2014). Neuroprotection by acetyl-11-keto-beta-Boswellic acid, in ischemic brain injury involves the Nrf2/HO-1 defense pathway. Sci. Rep. 4, 7002. 10.1038/srep07002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Chen M., Wang M., Li Y., Wen A. (2015). Posttreatment with 11-keto-beta-boswellic acid ameliorates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury: Nrf2/HO-1 pathway as a potential mechanism. Mol. Neurobiol. 52 (3), 1430–1439. 10.1007/s12035-014-8929-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q., Yao J., Fang J. N., Ding K. (2007). Structural characterization and immunological activity of two cold-water extractable polysaccharides from Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma. Carbohydr. Res. 342 (10), 1343–1349. 10.1016/j.carres.2007.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnan G. A., Fisher M., Macleod M., Davis S. M. (2008). Stroke. Lancet 371 (9624), 1612–1623. 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60694-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Q., Si E. (2019). MicroRNA-25 aggravates Abeta1-42-induced hippocampal neuron injury in Alzheimer's disease by downregulating KLF2 via the Nrf2 signaling pathway in a mouse model. J. Cell Biochem. 120 (9), 15891–15905. 10.1002/jcb.28861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElAli A. (2016). The implication of neurovascular unit signaling in controlling the subtle balance between injury and repair following ischemic stroke. Neural Regener. Res. 11 (6), 914–915. 10.4103/1673-5374.184485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaire B. P. (2018). Herbal medicine in ischemic stroke: challenges and prospective. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 24 (4), 243–246. 10.1007/s11655-018-2828-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Jiang Y., Dai F., Han Z., Liu H., Bao Z., et al. (2015). Study on laxative constituents in Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma. Mod. Chin. Med. 17 (04), 19–22+26. 10.13313/j.issn.1673-4890.2015.4.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X., Xu Y., Ren K., Bai X., Zhang C., Li M. (2019). Phenylethanoid glycosides from Paraboea martinii protect rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced cell injury. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 83 (12), 2202–2212. 10.1080/09168451.2019.1654359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C., Ward N. S. (2014). Cortical reorganization after stroke: how much and how functional? Neuroscientist 20 (1), 56–70. 10.1177/1073858413491147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzik A., Bushnell C. (2017). Stroke epidemiology and risk factor management. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 23 (1, Cerebrovascular Dis), 15–39. 10.1212/con.0000000000000416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Wu Y., Zhao B., Hu H., Zhu B., Sun Z., et al. (2018). Panax notoginseng Saponins protect cerebral microvascular endothelial cells against oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion-induced barrier dysfunction via activation of PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 antioxidant signaling pathway. Molecules 23 (11), 1–17. 10.3390/molecules23112781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasawa E., Ichijo M., Ishibashi S., Yokota T. (2016). Acute development of collateral circulation and therapeutic prospects in ischemic stroke. Neural Regener. Res. 11 (3), 368–371. 10.4103/1673-5374.179033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S., Li S., Zhao X., Kang N., Cao K., Zhu Y., et al. (2019). Protective role of phenylethanoid glycosides, Torenoside B and Savatiside A, in Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 17 (5), 3755–3767. 10.3892/etm.2019.7355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Tu P. F. (2009). Analysis of chemical constituents in Cistanche species. J. Chromatogr. A 1216 (11), 1970–1979. 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Yu J. T., Zhu X. C., Wang H. F., Tan M. S., Cao L., et al. (2014). Acute metformin preconditioning confers neuroprotection against focal cerebral ischaemia by pre-activation of AMPK-dependent autophagy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171 (13), 3146–3157. 10.1111/bph.12655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Andjelkovic A. V., Zhu L., Yang T., Bennett M. V. L., Chen J., et al. (2018). Blood-brain barrier dysfunction and recovery after ischemic stroke. Prog. Neurobiol. 163-164, 144–171. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. E., Kim G. S., Chen H., Maier C. M., Narasimhan P., Song Y. S., et al. (2010). Reperfusion and neurovascular dysfunction in stroke: from basic mechanisms to potential strategies for neuroprotection. Mol. Neurobiol. 41 (2-3), 172–179. 10.1007/s12035-010-8102-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C., Browne W. J., Cuthill I. C., Emerson M., Altman D. G. (2010). Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 8 (6), e1000412. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko K. M., Leung H. Y. (2007). Enhancement of ATP generation capacity, antioxidant activity and immunomodulatory activities by Chinese Yang and Yin tonifying herbs. Chin. Med. 2, 3. 10.1186/1749-8546-2-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo T., Reaume A. G., Huang T. T., Carlson E., Murakami K., Chen S. F., et al. (1997). Reduction of CuZn-superoxide dismutase activity exacerbates neuronal cell injury and edema formation after transient focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosci. 17 (11), 4180–4189. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M., Saver J. L., Alger J. R., Hao Q., Starkman S., Ali L. K., et al. (2012). Blood-brain barrier permeability derangements in posterior circulation ischemic stroke: frequency and relation to hemorrhagic transformation. J. Neurol. Sci. 313 (1-2), 142–146. 10.1016/j.jns.2011.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Wang J., Ma J., Gu Z., Jiang C., Yu L., et al. (2015). Neuroprotective effects of cistanches herba therapy on patients with moderate alzheimer's disease. Evid Based Complement Altern. Med. 2015, 103985. 10.1155/2015/103985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Xu T., Zhou F., Wang M., Song H., Xiao X., et al. (2018). Neuroprotective effects of four phenylethanoid glycosides on H(2)O(2)-induced apoptosis on PC12 cells via the Nrf2/ARE pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (4), 1–17. 10.3390/ijms19041135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Zhao M., Tu P., Jiang Y. (2019). Simultaneous determination of five phenylethanoid glycosides in Cistanches Herba using quantitative analysis of multi-components by single marker. J. Chin. Pharm. Sci. 28 (08), 537–546. 10.5246/jcps.2019.08.051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lian J., Wang L., Zhao F., Lin S., Yan X., Jia J., et al. (2017). Effects of glycosides of cistanche on synaptic morphological plasticity in senescence accelerated mice. J. Baotou Medl Coll. 33 (08), 78–80. 10.16833/j.cnki.jbmc.2017.08.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang D., Wang H., Qu Y., Xiao X., Zhu Y. (2014). The protective effect of HET0016 on brain edema and blood-brain barrier dysfunction after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Brain Res. 1544, 45–53. 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Zhang R., Liu D., Wang J., Yuan C., Zhao X., et al. (2018). Time-course investigation of blood-brain barrier permeability and tight junction protein changes in a rat model of permanent focal ischemia. J. Physiol. Sci. 68 (2), 121–127. 10.1007/s12576-016-0516-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Chang L., Wei C. (2019). The sonic hedgehog pathway mediates Tongxinluo capsule-induced protection against blood-brain barrier disruption after ischaemic stroke in mice. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 124 (6), 660–669. 10.1111/bcpt.13186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C. W., Lin T. Y., Huang S. K., Wang S. J. (2016). Echinacoside inhibits glutamate release by suppressing voltage-dependent Ca(2+) entry and protein kinase C in rat cerebrocortical nerve terminals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 (7), 1–13. 10.3390/ijms17071006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J. C., Drummond G. B., McLachlan E. M., Kilkenny C., Wainwright C. L. (2010). Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160 (7), 1573–1576. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentor S., Fisher D. (2017). Aggressive antioxidant reductive stress impairs brain endothelial cell angiogenesis and blood brain barrier function. Curr. Neurovasc Res. 14 (1), 71–81. 10.2174/1567202613666161129113950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti A., Ferrari F., Villa R. F. (2015). Neuroprotection for ischaemic stroke: current status and challenges. Pharmacol. Ther. 146, 23–34. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyul-Toth A., Suciu M., Molnar J., Fazakas C., Hasko J., Herman H., et al. (2016). Differences in the molecular structure of the blood-brain barrier in the cerebral cortex and white matter: an in silico, in vitro, and ex vivo study. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 310 (11), H1702–H1714. 10.1152/ajpheart.00774.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovbiagele B., Nguyen-Huynh M. N. (2011). Stroke epidemiology: advancing our understanding of disease mechanism and therapy. Neurotherapeutics 8 (3), 319–329. 10.1007/s13311-011-0053-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page S., Munsell A., Al-Ahmad A. J. (2016). Cerebral hypoxia/ischemia selectively disrupts tight junctions complexes in stem cell-derived human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Fluids Barriers CNS 13 (1), 16. 10.1186/s12987-016-0042-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng F., Chen J., Wang X., Xu C., Liu T., Xu R. (2016). Changes in levels of phenylethanoid glycosides, antioxidant activity, and other quality traits in cistanche deserticola slices by steam processing. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 64 (7), 1024–1030. 10.1248/cpb.c16-00033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestley J. R. C., Fink K. E., McCord J. M., Lombard J. H. (2019). NRF2 activation with protandim attenuates salt-induced vascular dysfunction and microvascular rarefaction. Microcirculation, 26 (7), e12575. 10.1111/micc.12575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saboor F., Reckmann A. N., Tomczyk C. U., Peters D. M., Weissmann N., Kaschtanow A., et al. (2016). Nestin-expressing vascular wall cells drive development of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 47 (3), 876–888. 10.1183/13993003.00574-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T., Okamoto S. I., Cui J., Watanabe Y., Furuta K., Suzuki M., et al. (2006). Activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway for neuroprotection by electrophilic [correction of electrophillic] phase II inducers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 (3), 768–773. 10.1073/pnas.0505723102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellinger P. D., Kohrmann M. (2014). 4.5-hour time window for intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator is established firmly. Stroke 45 (3), 912–913. 10.1161/strokeaha.113.002700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealy-Jefferson S., Wing J. J., Sanchez B. N., Brown D. L., Meurer W. J., Smith M. A., et al. (2012). Age- and ethnic-specific sex differences in stroke risk. Gend Med. 9 (2), 121–128. 10.1016/j.genm.2012.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z., Wu Y., Zhu Y., Cui, Wang M., Yin H., et al. (2019). Quantitative determination of betaine, mannitol, fructose, glucose and sucrose in Cistanches Herba by HPLC-ELSD. Mod. Chin. Med. 32 (6), 1–11. 10.13313/j.issn.1673-4890.20190320006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D., Reeta K. H., Sharma U., Jagannathan N. R., Dinda A. K., Gupta Y. K. (2019). Neuro-protective effect of monomethyl fumarate on ischemia reperfusion injury in rats: Role of Nrf2/HO1 pathway in peri-infarct region. Neurochem. Int. 126, 96–108. 10.1016/j.neuint.2019.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siow R. C., Ishii T., Mann G. E. (2007). Modulation of antioxidant gene expression by 4-hydroxynonenal: atheroprotective role of the Nrf2/ARE transcription pathway. Redox Rep. 12 (1), 11–15. 10.1179/135100007x162167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda S., Katsura K., Kanamaru T., Saito M., Katayama Y. (2013). Valproic acid attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat brain through inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 707 (1-3), 26–31. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Yamamoto M. (2015). Molecular basis of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88 (Pt B), 93–100. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenreiro M. M., Ferreira R., Bernardino L., Brito M. A. (2016). Cellular response of the blood-brain barrier to injury: Potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for brain regeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 91, 262–273. 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. W., Narayanan S. V., Koronowski K. B., Morris-Blanco K., Dave K. R., Perez-Pinzon M. A. (2015). Signaling pathways leading to ischemic mitochondrial neuroprotection. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 47 (1-2), 101–110. 10.1007/s10863-014-9574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Zhang X., Xie W. (2012). Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma, “Desert ginseng”: a review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 40 (6), 1123–1141. 10.1142/s0192415x12500838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wang S., Wang J., Guo H., Dong Z., Chai L., et al. (2015). Neuroprotective effect of xueshuantong for injection (lyophilized) in transient and permanent rat cerebral ischemia model. Evid Based Complement Altern. Med. 2015, 134685. 10.1155/2015/134685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Wang H., Gu L. (2017). The antidepressant and cognitive improvement activities of the traditional chinese herb cistanche. Evid Based Complement Altern. Med. 2017, 3925903. 10.1155/2017/3925903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. J., Wang S. X., Chai L. J., Zhang Y., Guo H., Hu L. M. (2018). Xueshuantong injection (lyophilized) combined with salvianolate lyophilized injection protects against focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats through attenuation of oxidative stress. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 39 (6), 998–1011. 10.1038/aps.2017.128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Gong J., Thimmulappa R. K., Kosmider B., Biswal S., Duh E. J. (2013). Nrf2 acts cell-autonomously in endothelium to regulate tip cell formation and vascular branching. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110 (41), E3910–E3918. 10.1073/pnas.1309276110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia D., Zhang Z., Zhao Y. (2018). Acteoside attenuates oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis in rats with focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 41 (11), 1645–1651. 10.1248/bpb.b18-00210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W., MacColl Garfinkel A. E., Li Y., Benowitz L. I., Cepko C. L. (2015). NRF2 promotes neuronal survival in neurodegeneration and acute nerve damage. J. Clin. Invest. 125 (4), 1433–1445. 10.1172/jci79735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. T., Zhang C. G., He Y. Q., Shi S. S., Wang Y. L., Chou G. X. (2019). Phenylethanoid glycosides from the Schnabelia nepetifolia (Benth.) P.D.Cantino promote the proliferation of osteoblasts. Phytochemistry 164, 111–121. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ya B. L., Liu Q., Li H. F., Cheng H. J., Yu T., Chen L., et al. (2018). Uric acid protects against focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative stress via activating Nrf2 and regulating neurotrophic factor expression. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev 2018, 6069150. 10.1155/2018/6069150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z. Y., Xing H. Y., Wang B., Liu M., Lv P. Y. (2019). DL-3-n-butylphthalide protects the blood-brain barrier against ischemia/hypoxia injury via upregulation of tight junction proteins. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 132 (11), 1344–1353. 10.1097/cm9.0000000000000232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q., Li X., Cao X. (2016). Cardioprotective effects of phenylethanoid glycoside-rich extract from Cistanche deserticola in ischemia-reperfusion-induced myocardial infarction in rats. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 34, 234–242. 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N., Wang Z., Chen Y., Yang J., Lu X., Guo Y., et al. (2017). The ameliorative effect of bloodletting puncture at hand twelve Jing-well points on cerebral edema induced by permanent middle cerebral ischemia via protecting the tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 17 (1), 470. 10.1186/s12906-017-1979-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W., Gao D., Jin W., Liu S., Qi S. (2018). Propofol prevents oxidative stress by decreasing the ischemic accumulation of succinate in focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Neurochem. Res. 43 (2), 420–429. 10.1007/s11064-017-2437-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen C. M., Chung S. Y., Tsai T. H., Sung P. H., Huang T. H., Chen Y. L., et al. (2015). Extracorporeal shock wave effectively attenuates brain infarct volume and improves neurological function in rat after acute ischemic stroke. Am. J. Transl. Res. 7 (6), 976–994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechariah A., ElAli A., Doeppner T. R., Jin F., Hasan M. R., Helfrich I., et al. (2013). Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes pericyte coverage of brain capillaries, improves cerebral blood flow during subsequent focal cerebral ischemia, and preserves the metabolic penumbra. Stroke 44 (6), 1690–1697. 10.1161/strokeaha.111.000240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. Y., Wang Z. J., Sun D. M., Wang Y., Xu P., Wu W. J., et al. (2017). Novel therapeutic tffects of teonurine on ischemic stroke: new mechanisms of BBB integrity. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev 2017, 7150376. 10.1155/2017/7150376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Xu M., Wang Y., Xie F., Zhang G., Qin X. (2017). Nrf2-a promising therapeutic target for defensing against oxidative stress in stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 54 (8), 6006–6017. 10.1007/s12035-016-0111-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A., Yang X., Li Q., Yang Y., Zhao G., Wang B., et al. (2018). Immunostimulatory activity of water-extractable polysaccharides from Cistanche deserticola as a plant adjuvant in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 13 (1), e0191356. 10.1371/journal.pone.0191356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang K., Chen H., He R., Cai R., Li J., et al. (2018). Anti-inflammatory lignans and phenylethanoid glycosides from the root of Isodon ternifolius (D.Don) Kudo. Phytochemistry 153, 36–47. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Zhang Q., Deng J., Li J., Li J., Wen L., et al. (2019). ALK5 signaling pathway mediates neurogenesis and functional recovery after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats via Gadd45b. Cell Death Dis. 10 (5), 360. 10.1038/s41419-019-1596-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.