Abstract

Introduction

Each dermatological condition associated with the presence of visible skin lesions can evoke the following psychological response of the patient: shame, anxiety, anger, or even depression. Psoriasis may additionally be a cause of social rejection, which significantly impairs a patient’s private life and social functioning, and may contribute to stigmatization, alienation, and deterioration of their quality of life. The aim of the study was to determine the level of stigmatization and the quality of life of persons with psoriasis in relation to sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

The study, which included 166 patients with plaque psoriasis, was carried out with the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and a dedicated sociodemographic survey.

Results

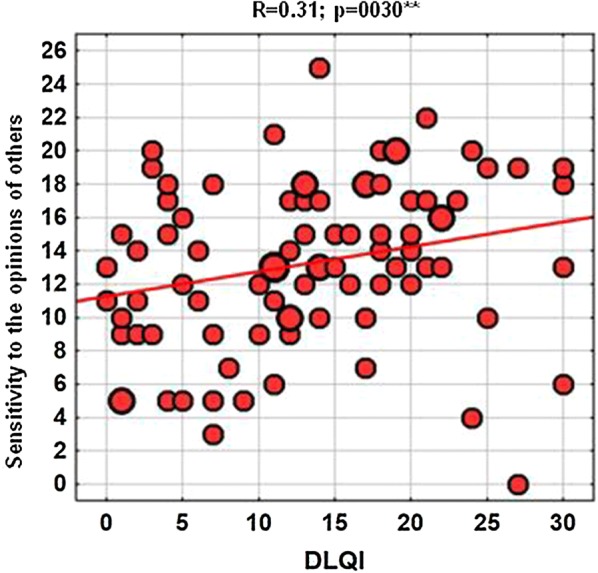

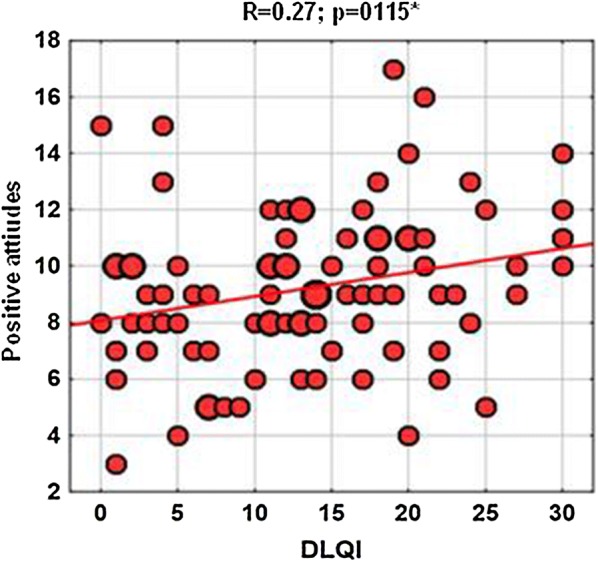

Compared with women, men had higher stigmatization scores in the “Feeling of being flawed” domain (p = 0.0362), and patients up to 30 years of age scored higher on the “Guilt and shame” domain ( = 17.1 points) than those older than 30 years ( = 14.6 points). Also, persons with visible skin lesions presented with higher stigmatization levels in the “Guilt and shame” domain than those without (p = 0.0028). Quality of life in persons with psoriasis did not depend on sociodemographic parameters but correlated significantly with two stigmatization domains, “Sensitivity to the opinions of others” (R = 0.31; p = 0.0030) and “Positive attitudes” (R = 0.27; p = 0.0115).

Conclusions

As stigmatization is a social problem, only greater social awareness of psoriasis may contribute to better understanding and broader acceptance of patients with this dermatosis. To help them to cope with the stigmatization and hence to improve their quality of life, persons with psoriasis should be provided with psychological counselling.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Quality of life, Stigmatization

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| As a chronic skin condition characterized by periods of remission and recurrence and the necessity for long-term treatment, psoriasis significantly affects the patients’ quality of life |

| This negatively affects the everyday functioning of patients with psoriasis who frequently feel excluded and have decreased self-image and self-esteem, which is reflected by their impression of being stigmatized |

| What was learned from the study? |

| As stigmatization is a social problem, only greater social awareness of psoriasis may contribute to better understanding and broader acceptance of patients with this dermatosis |

| To help them to cope with the stigmatization and hence to improve their quality of life, patients with psoriasis should be provided with psychological counselling |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic recurrent disease of the skin associated with a benign proliferation of epidermal cells and immunological disorders. Psoriasis may have a few clinical forms that differ in terms of the location of skin lesions, severity, and duration. Typically, psoriasis manifests as red plaques covered with silvery-white scaly skin [1].

Visible psoriatic lesions present on exposed body parts may induce fear, disgust, aversion, or even intolerance [2]. Furthermore, some people with limited awareness of psoriasis believe that the disease is contagious, which may eventually contribute to the social isolation of persons with psoriasis [3, 4].

Patients with psoriasis often experience stigmatization and denial [2, 5, 6]. In line with Goffman’s theory, stigmatized persons are rejected as a result of having an attribute which is deeply discredited by their society [7]. There are two types of stigma, social stigma and self-stigma. The social stigma occurs whenever members of society reject or exclude the individuals who are different from others, treating them in an unfair and discriminative manner [8, 9]. The self-stigma happens if a person presents with low self-esteem and the feelings of shame and hopelessness because of an illness [10]. The self-stigmatized individuals believe that they possess a specific disease-related trait that is socially unaccepted, which makes this trait critical to them and leads to a gradual change in their self-image. The self-stigmatized persons consider themselves worse and underestimate their value, even if they have never experienced social stigmatization and others are unaware of their defect [11]. Hence, such patients self-stigmatize themselves in terms of labeling, and in fact their self-stigmatization results from the lack of illness acceptance and self-acceptance in general [12].

While social stigmatization and self-stigmatization may occur independently of each other, they may also co-exist [9].

Internalization of the illness-related stigma may produce a feeling of guilt, and often the fear of being assessed by others may jeopardize one’s emotional status and even lead to mental illness [13–15]. Persons with psoriasis are vulnerable to comments and remarks about their disease, which not infrequently results in social withdrawal, and may develop depression or even undertake suicide attempts [16, 17].

Chronic stress associated with stigmatization, lack of acceptance from others, and a necessity to cope with the chronic disease have a considerable effect on the quality of life of persons with psoriasis [17]. In tandem with deteriorated quality of life, patients with psoriasis may experience loneliness, which further impairs their social functioning. The feeling of loneliness is a consequence of physical and mental ailments, and a result of psychological disturbances, such as a decrease in self-esteem, inability to establish social contacts, and stigmatization [3, 18].

The results of recent studies suggest that patients with some dermatological conditions may benefit from psychological intervention. Psychological support may be a valuable addition to medical care, especially in patients in whom skin lesions are a cause of an evident esthetic defect and related discomfort, as it is the case in psoriasis [5, 16, 18, 19]. Previous studies did not identify the interventions that would effectively attenuate the sense of stigmatization. Furthermore, it should be remembered that the interventions developed in one country may not necessarily be effective in another as a result of the overlapping effect of cultural and socioeconomic factors [9].

Psychological interventions combined with relaxation training are beneficial in terms of coping with stress and self-esteem; therefore, designing a psychological intervention program, one should consider patients’ opinions and attitudes to their illness, the level of self-acceptance, and emotions associated with the disease. Consideration of non-pharmacological interventions, such as biofeedback, relaxation training, and cognitive behavioral therapy, in the management of psoriasis, may improve the quality of life of the patients [20].

The sense of stigmatization can be diminished not only through psychological interventions aimed at intrapersonal activities but also through interpersonal activities, such as [9, 21–24]:

Modification of false information that may distort the self-image of patients with dermatological conditions, through the implementation of mass media-based social education campaigns to change the existing stereotypes (lectures, posters, leaflets)

Broadly defined health education promoting knowledge and skills, and offering counselling to the patients

Contact of stigmatized persons with support groups to help them realize that they can avoid negative consequences of stigmatization, which will eventually contribute to their higher self-esteem and better quality of life

A strength of this study stems from the fact that it analyzed a relationship between the quality of life and the sense of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis, whereas most previous studies centered around only one of these aspects. Hence, the results add considerably to our knowledge of the problem in question and might stimulate further research in this matter.

The aim of the study was to determine the level of stigmatization and the quality of life of persons with psoriasis in relation to sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

The study included 166 patients with plaque psoriasis (55.6% were women and 44.3% were men) with Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) scores of 10 or less. The inclusion criteria of the study were duration of psoriasis more than 2 years, age at least 18 years, and lack of other somatic or mental disorders during 3 months preceding the study.

The age of the study patients ranged between 18 and 72 years ( = 37.4; Me = 38; s = 11.0). Mean age at the diagnosis of psoriasis was 21.5 years (Me = 20; s = 9.1) and duration of the disease varied from 2 to 59 years ( = 15.8; Me = 15; s = 11.3).

In the study group, 54.5% of persons were married, 28.4% were single, 11.4% were divorcees, and 5.7% were widows/widowers. The proportions of respondents with higher and secondary education were 50% and 31.8%, respectively. The vast majority of the study participants were city dwellers (75%) and employed persons (85.2%).

The study patients completed Polish versions of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and a survey developed by the authors of this study that contained questions about sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (gender, age, place of residence, marital status, education, employment status) and information about their disease (location of psoriatic lesions, time elapsed since the diagnosis of psoriasis).

The 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire consists of 33 single-choice questions. In the Polish version of the instrument, the answer to each question can be scored on a scale from 0 to 5, where 5 corresponds to “definitely yes”, 4 to “yes”, 3 to “rather yes”, 2 to “rather no”, 1 to “no”, and 0 to “definitely no”. The scale for questions no. 9, 11, 12, 16, 17, 20, 23, 25, and 33 is inverted, so regardless of the question, higher score corresponds to higher stigmatization level. The questionnaire is used to determine the level of disease-related stigmatization in six domains: (1) anticipation of rejection, (2) feeling of being flawed, (3) sensitivity to the opinions of others, (4) guilt and shame, (5) positive attitudes, and (6) secretiveness. The overall score of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire can range from 0 points (lack of stigmatization) to 165 points (maximum stigmatization level) [25].

DLQI contains 10 single-choice questions referring to the quality of life in dermatological disorders. The answer to each question is scored on a scale from 0 to 3, where 3 corresponds to “very much”, 2 to “a lot”, 1 to “a little”, and 0 to “not at all”. The overall DLQI score can range from 0 to 30. The higher the score is, the worse the quality of life in a given patient is [26].

The protocol of the study was approved by the Local Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Bialystok. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Statistical Analysis

The results for nominal variables are presented in tables, as descriptive statistics for all psychometric measures, along with the information about the significance of between-group differences. The latter was verified with the Student t test for independent samples. The results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Relationships between pairs of quantitative variables were analyzed on the basis of the Spearman’s coefficients of rank correlation. The power of the relationship was interpreted as follows [27]:

|R| < 0.3—no correlation

0.3 ≤ |R| < 0.5—weak correlation

0.5 ≤ |R| < 0.7—moderate correlation

0.7 ≤ |R| < 0.9—strong correlation

0.9 ≤ |R| < 1—very strong correlation

|R| = 1—ideal correlation

Additionally, the test for the significance of correlation coefficients (p) was conducted to verify whether the relationship found in the sample reflected the association in the general population or was random. The results were considered significant at p < 0.05.

A stepwise regression analysis with forward selection was carried out to identify the statistically significant factors that explained the differences in the stigmatization levels.

The statistical analysis was carried out with the STATISTICA 12.5 package.

Results

A statistically significant gender-related difference was observed in the case of only one item of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire (33-i.s.), the “Feeling of being flawed” (p = 0.0362), with men presenting with higher stigmatization levels than women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Stigmatization levels and quality of life according to patient gender

| Psychometric measures | Gender | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (N = 49) | Men (N = 39) | ||||||

| s | 95% CI | s | 95% CI | ||||

| Stigmatization domains (33-i.s.) | |||||||

| Anticipation of rejection | 21.3 | 5.7 | 19.7–23.0 | 22.6 | 7.6 | 20.2–25.1 | 0.3657 |

| Feeling of being flawed | 12.8 | 4.6 | 11.4–14.1 | 15.2 | 6.0 | 13.2–17.1 | 0.0362* |

| Sensitivity to the opinions of others | 12.7 | 4.2 | 11.4–13.9 | 14.0 | 5.7 | 12.2–15.8 | 0.2054 |

| Guilt and shame | 15.3 | 3.2 | 14.4–16.2 | 15.2 | 4.1 | 13.9–16.5 | 0.8697 |

| Positive attitudes | 9.1 | 2.6 | 8.3–9.8 | 9.4 | 2.9 | 8.4–10.3 | 0.5844 |

| Secretiveness | 10.8 | 3.4 | 9.8–11.8 | 11.4 | 4.0 | 10.1–12.6 | 0.4889 |

| DLQI | 12.5 | 8.4 | 10.1–14.9 | 14.3 | 7.7 | 11.8–16.8 | 0.2978 |

arithmetic mean, s standard deviation, 95% CI 95% confidence interval for mean value in a given population

p values from the Student t test

* indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

The results were also stratified according to age, under 30 years and 30 years or more. The only significant age-related difference was observed for the “Guilt and shame” domain score (p = 0.0028), with higher values found in younger patients ( = 17.1 points; s = 4.1; 95% CI 15.4–18.9) than in those aged 30 years or more ( = 14.6 points; s = 3.1; 95% CI 13.8–15.4) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Stigmatization levels and quality of life according to patient age

| Psychometric measures | Patient age | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 30 (N = 23) | ≥ 30 (N = 65) | ||||||

| s | 95% CI | s | 95% CI | ||||

| Stigmatization domains (33-i.s.) | |||||||

| Anticipation of rejection | 22.0 | 7.7 | 18.6–25.3 | 21.9 | 6.2 | 20.3–23.4 | 0.9607 |

| Feeling of being flawed | 13.5 | 6.7 | 10.6–16.4 | 13.9 | 4.8 | 12.7–15.1 | 0.7255 |

| Sensitivity to the opinions of others | 13.6 | 6.0 | 11.0–16.2 | 13.1 | 4.6 | 12.0–14.3 | 0.6876 |

| Guilt and shame | 17.1 | 4.1 | 15.4–18.9 | 14.6 | 3.1 | 13.8–15.4 | 0.0028** |

| Positive attitudes | 9.0 | 2.5 | 7.9–10.1 | 9.3 | 2.8 | 8.6–10.0 | 0.7444 |

| Secretiveness | 10.3 | 4.2 | 8.5–12.1 | 11.3 | 3.4 | 10.5–12.2 | 0.2493 |

| DLQI | 12.5 | 8.9 | 8.6–16.3 | 13.6 | 7.8 | 11.6–15.5 | 0.5760 |

p values from the Student t test

** indicate strong statistical significance (p < 0.01)

The number of statistically significant differences increased when the results were stratified according to the time elapsed since the diagnosis of psoriasis. Patients with a longer history of psoriasis presented with higher stigmatization levels in the “Feeling of being flawed” and “Secretiveness” domains than those in whom the disease was diagnosed more recently (Table 3).

Table 3.

Stigmatization levels and quality of life according to the duration of psoriasis

| Psychometric measures | Duration of psoriasis | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 15 (N = 41) | ≥ 15 (N = 43) | ||||||

| s | 95% CI | s | 95% CI | ||||

| Stigmatization domains (33-i.s.) | |||||||

| Anticipation of rejection | 21.3 | 6.5 | 19.2–23.4 | 22.8 | 6.7 | 20.7–24.8 | 0.3020 |

| Feeling of being flawed | 12.3 | 5.1 | 10.7–13.9 | 15.2 | 5.4 | 13.6–16.9 | 0.0142* |

| Sensitivity to the opinions of others | 12.3 | 4.8 | 10.8–13.8 | 14.0 | 5.1 | 12.4–15.6 | 0.1136 |

| Guilt and shame | 15.8 | 3.5 | 14.7–16.9 | 14.9 | 3.7 | 13.7–16.0 | 0.2327 |

| Positive attitudes | 8.7 | 2.3 | 7.9–9.4 | 9.6 | 2.8 | 8.7–10.4 | 0.1025 |

| Secretiveness | 10.2 | 3.7 | 9.0–11.4 | 11.8 | 3.5 | 10.8–12.9 | 0.0393* |

| DLQI | 11.8 | 7.9 | 9.3–14.3 | 15.0 | 8.0 | 12.6–17.5 | 0.0670 |

p values from the Student t test

* indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

Patient age turned out to correlate inversely with the “Guilt and shame” scores (R = − 0.35; p = 0.0009), and duration of the disease correlated positively with the “Secretiveness” levels (R = 0.25; p = 0.0240). The latter finding was consistent with the result of the between-group comparison mentioned above, confirming that a longer history of psoriasis was associated with higher “Secretiveness” scores (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations of stigmatization levels and quality of life with patient age and duration of psoriasis

| Psychometric measures | Age | Duration of psoriasis |

|---|---|---|

| Stigmatization domains (33-i.s.) | ||

| Anticipation of rejection | 0.00 (p = 0.9705) | 0.03 (p = 0.8029) |

| Feeling of being flawed | 0.09 (p = 0.3896) | 0.18 (p = 0.1074) |

| Sensitivity to the opinions of others | − 0.01 (p = 0.9358) | 0.04 (p = 0.7097) |

| Guilt and shame | − 0.35 (p = 0.0009***) | − 0.17 (p = 0.1278) |

| Positive attitudes | − 0.05 (p = 0.6520) | 0.09 (p = 0.4329) |

| Secretiveness | 0.17 (p = 0.1213) | 0.25 (p = 0.0240*) |

| DLQI | 0.00 (p = 0.9764) | 0.12 (p = 0.2725) |

p values for Spearman’s coefficients of rank correlation (R)

*** indicate very strong statistical significance (p < 0.001)

We also verified whether the location of psoriatic lesions affected the stigmatization levels. The study patients were divided into two groups: (1) patients with psoriatic lesions on exposed body parts (eyelids, face, head, neck, whole body) and (2) patients with lesions solely on body parts invisible to others. We assumed that the presence of psoriatic lesions on body parts that are exposed during the activities of daily living might be reflected by higher stigmatization levels.

Indeed, persons with psoriatic lesions on exposed body parts presented with significantly higher scores for the “Guilt and shame” domain (mean 15.9 points vs. 14.4 points; p = 0.0360) and higher, at a threshold of statistical significance (p = 0.0725) stigmatization scores for the “Anticipation of rejection” domain (22.9 points vs. 20.4 points) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Stigmatization levels and quality of life according to the presence of psoriatic lesions on exposed and unexposed body parts

| Psychometric measures | Presence of psoriatic lesions on exposed and unexposed body parts | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 36) | Yes (N = 52) | ||||||

| s | 95% CI | s | 95% CI | ||||

| Stigmatization domains (33-i.s.) | |||||||

| Anticipation of rejection | 20.4 | 7.1 | 18.0–22.8 | 22.9 | 6.1 | 21.3–24.6 | 0.0725 |

| Feeling of being flawed | 13.6 | 5.3 | 11.8–15.4 | 14.0 | 5.5 | 12.4–15.5 | 0.7324 |

| Sensitivity to the opinions of others | 12.8 | 4.8 | 11.1–14.4 | 13.6 | 5.1 | 12.2–15.0 | 0.3863 |

| Guilt and shame | 14.4 | 3.0 | 13.3–15.4 | 15.9 | 3.8 | 14.8–16.9 | 0.0360* |

| Positive attitudes | 9.6 | 2.9 | 8.6–10.5 | 9.0 | 2.6 | 8.2–9.7 | 0.3122 |

| Secretiveness | 11.0 | 3.3 | 9.9–12.1 | 11.1 | 3.9 | 10.0–12.2 | 0.9562 |

| DLQI | 13.4 | 8.2 | 10.7–16.2 | 13.2 | 8.1 | 10.9–15.4 | 0.8296 |

p values from the Student t test

* indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

A significant difference in the scores for the “Guilt and shame” domain was also found between married ( = 14.6 points; s = 3.0; 95% CI 13.7–15.4) and unmarried patients ( = 16.1 points; s = 4.0; 95% CI 14.8–17.4), with p = 0.0470 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Stigmatization levels and quality of life according to the marital status of patients with psoriasis

| Psychometric measures | Marital status | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married (N = 48) | Unmarried (N = 40) | ||||||

| s | 95% CI | s | 95% CI | ||||

| Stigmatization domains (33-i.s.) | |||||||

| Anticipation of rejection | 21.4 | 6.0 | 19.6–23.1 | 22.6 | 7.2 | 20.2–24.9 | 0.4004 |

| Feeling of being flawed | 13.5 | 4.9 | 12.1–15.0 | 14.2 | 5.9 | 12.3–16.0 | 0.5987 |

| Sensitivity to the opinions of others | 13.0 | 4.3 | 11.7–14.2 | 13.6 | 5.7 | 11.8–15.4 | 0.5759 |

| Guilt and shame | 14.6 | 3.0 | 13.7–15.4 | 16.1 | 4.0 | 14.8–17.4 | 0.0470* |

| Positive attitudes | 9.0 | 2.8 | 8.2–9.8 | 9.4 | 2.6 | 8.6–10.3 | 0.4930 |

| Secretiveness | 11.0 | 3.2 | 10.1–11.9 | 11.1 | 4.2 | 9.8–12.4 | 0.9195 |

| DLQI | 12.2 | 7.8 | 9.9–14.4 | 14.7 | 8.3 | 12.0–17.3 | 0.1528 |

p values from the Student t test

* indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05)

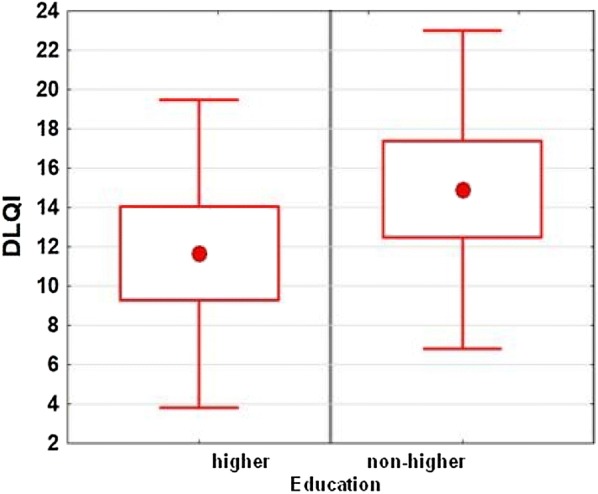

The effects of education on the stigmatization levels and the quality of life were analyzed within the groups of patients with higher and non-higher education. DLQI score was the only parameter for which the between-group difference was at a threshold of statistical significance (p = 0.0574), with the scores for higher and non-higher education groups of = 11.7 points (s = 7.8; 95% CI 9.3–14.0) and = 14.9 points (s = 8.1; 95% CI 12.5–17.4), respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between the education of patients with psoriasis and DLQI scores

We also analyzed the relationships between the quality of life, determined with the DLQI questionnaire, and the stigmatization indices. Among the six domains of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, the strongest correlations with the DLQI scores were found for the “Sensitivity to the opinions of others” (R = 0.31; p = 0.0030) and “Positive attitudes” (R = 0.27; p = 0.0115). The relationships with correlation coefficients higher than 0.25 are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between the quality of life and the scores for the “Sensitivity to the opinions of others” domain of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire

Fig. 3.

Correlation between the quality of life and the scores for the “Positive attitudes” domain of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire

To complement the results of the univariate analyses, linear regression analyses were carried out with various measures of stigmatization as the dependent variable and quantitative and dichotomous parameters as independent predictors:

Gender (women vs. men)

Age (< 30 vs. ≥ 30, as numerical variable)

Duration of psoriasis (< 15 vs. ≥ 15, as numerical variable)

Presence of psoriatic lesions on exposed and unexposed body parts (yes vs. no)

Marital status (married vs. unmarried)

Level of education (higher vs. non-higher)

Additionally, stepwise regression analysis with forward selection was conducted to identify the statistically significant factors that explained the differences in the stigmatization levels.

No statistically significant independent predictors were identified for the “Anticipation of rejection”, “Sensitivity to the opinions of others”, and “Positive attitudes” variables.

In line with the results of the univariate analyses, a single significant independent predictor was identified for each of the remaining variables, gender for the “Feeling of being flawed”, age for the “Guilt and shame”, and duration of the disease for the “Secretiveness”, respectively.

Discussion

As a chronic disease involving the skin, the largest human organ, psoriasis has a profound effect on the quality of life. Although not a life-threatening condition, psoriasis may significantly affect many aspects of a patients’ life. Previous studies demonstrated that one of the factors exerting a significant effect on the quality of life in psoriasis is stigmatization [2, 3, 17, 18, 21, 28].

According to Hawro et al. [29], the feeling of being rejected increases with age (p = 0.38), which, among others, manifests as avoidance of social contacts. However, in our present study, a stronger sense of stigmatization was observed in the younger group of patients with psoriasis (up to 30 years of age) and referred to only one domain of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, “Guilt and shame” (p = 0.0028). Higher levels of stigmatization in younger persons were previously also reported by Lu et al. [30].

According to Hawro et al. [29], the longer the duration of the disease is, the stronger the sense of rejection in people with psoriasis is (p = 0.33). Our results are consistent with this observation, as we found significant correlations between the time elapsed since the diagnosis of psoriasis and the scores for two domains of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire, “Feeling of being flawed” (p = 0.0142) and “Secretiveness” (p = 0.0393). Moreover, a longer duration of the disease turned out to be associated with worse quality of life, but this relationship was at a threshold of statistical significance (p = 0.0670). Van Beugen [31] and Ograczyk [32] also observed that older patients in whom psoriasis lasted longer reported more difficulties in social functioning.

Location of psoriatic lesions may be an essential determinant of psychosocial functioning. Our present study confirmed that the presence of skin lesions visible to others had a negative effect on both the sense of stigmatization and the quality of life. Similar results were reported previously by other authors [5, 29, 31]. However, in the study conducted by Hrehorów et al. [2], psoriatic lesions present on the face did not exert a significant effect on the stigmatization level. In another study [33] skin lesions located in the urogenital area, although not visible to the others, turned out to be a significant determinant of stigmatization during intimate relationships. Furthermore, it should be remembered that many persons with psoriasis do not accept their body image and hence self-stigmatize themselves, assuming that also others perceive them in a similar way [34].

According to Hawro et al. [29], female patients with psoriasis experienced stigmatization more often than male patients and had a worse quality of life. While similar findings were also reported by other authors [35, 36], the results in this matter are inconclusive. In some studies, these were men who evaluated their quality of life as worse [37, 38], and according to other authors, gender was not a significant determinant of the quality of life [2, 17, 30]. In our present study, the level of stigmatization in men was higher than in women, whereas the quality of life in female and male patients was essentially the same ( = 12.4 points vs. 14.3 points).

According to Lu et al. [30], worse educated patients with psoriasis more often experienced stigmatization and presented with higher stigmatization levels. A similar relationship was also reported by van Beugen et al. [31]. However, in our present study, we did not find statistically significant relationships between education and stigmatization levels. The only association at a threshold of statistical significance was found for DLQI scores (p = 0.0574), with patients with non-higher education presenting with worse quality of life than those with higher education (mean DLQI scores 14.9 points vs. 11.7 points).

A study of 102 psoriatic patients, conducted by Hrehorów et al. [2], did not demonstrate a link between the stigmatization level and clinical or demographic variables. The only exception pertained to considerably higher stigmatization levels in patients without a family history of psoriasis. Similar to our present study, Hrehorów et al. [2] also found significant correlations between the quality of life and most stigmatization dimensions measured with either the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire or the 6-item Stigmatization Scale.

Our present study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in the scores for the “Guilt and shame” domain of the 33-item Feelings of Stigmatization Questionnaire in married and unmarried patients. This relationship might reflect the fact that unmarried patients were younger than the married ones. Nevertheless, also in other studies [30, 31, 39], unmarried persons were shown to be more prone to stigmatization than married patients.

Interestingly, our study did not demonstrate a significant effect of employment status (employed vs. unemployed) and type of job (blue-collar workers vs. white-collar workers) on either the stigmatization levels or the quality of life. In the study conducted by Zimoląg et al. [40], psoriasis contributed to worse work ability; and according to Ginsburg and Link [39], persons with psoriasis who were employed experienced a stronger sense of rejection than unemployed ones.

The effect of psoriasis on the quality of life emerged as an important area of research in psychodermatology [28, 29, 32, 36, 37]. Our present study confirmed that both demographic and psychometric factors might influence the psychosocial status of persons with psoriasis, and stigmatization is a crucial problem present in many patients with psoriasis.

As every patient responds to his/her disease differently, the psychological effects of psoriasis may also vary from person to person. In extreme cases, psoriasis may be a trigger of depression or even constitute a reason behind a suicide attempt in patients who are unable to cope with their condition [2, 36]. This justifies further studies on stigmatization and quality of life in psoriasis. This future research should provide a complete, holistic insight into the condition of people with psoriasis, extending beyond the assessment of the disease severity and its effect on clinical status.

A potential limitation of the study might be the problem with obtaining a homogenous sample, free from comorbidities and other emergencies that might act as confounders.

Without a doubt, comparative analysis of our findings and the results of other studies of patients with different dermatoses would add considerably to this paper; however, we intended to focus exclusively on persons with psoriasis.

Conclusions

As stigmatization is a social problem, only greater social awareness of psoriasis may contribute to better understanding and broader acceptance of patients with this dermatosis.

To help them to cope with the stigmatization and hence to improve their quality of life, persons with psoriasis should be provided with psychological counselling.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in the survey.

Funding

This study and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Medical University of Bialystok, Poland. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Neither honoraria nor other forms of payments were made for authorship.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

Barbara Jankowiak, Beata Kowalewska, Elżbieta Krajewska-Kułak and Dzmitry F. Khvorik have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The protocol of the study was approved by the Local Bioethics Committee at the Medical University of Bialystok. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.11890032.

References

- 1.Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377–385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hrehorów E, Salomon E, Matusiak Ł, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Patients with psoriasis feel stigmatized. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2012;92:67–77. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kowalewska B, Krajewska-Kułak E, Jankowiak B, Łukaszuk C. Problem stygmatyzacji w dermatologii. Dermatologia Kliniczna. 2010;11:181–184. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, Vreeland MG, Wu Y. The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:383–392. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200506060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orion E, Wolf R. Psychologic consequences of facial dermatoses. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:767–771. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Link P. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;1:363–385. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss MG. Stigma and the social burden of neglected tropical diseases. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topp J, Andrees V, Weinberger NA, et al. Strategies to reduce sigma related to visible chronic skin diseases: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(11):2029–2038. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corker E, Hamilton S, Henderson C, Weeks C. Experiences of discrimination among people using mental health services in England 2008–2011. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(suppl 55):s58–s63. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2006;25:875–884. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell C, Deacon H. Unravelling the contexts of stigma: from internalisation to resistance to change. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;16:411–417. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuber J, Meyer I, Link B. Stigma, prejudice, discrimination and health. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picco L, Pang S, Lau YW, et al. Internalized stigma among psychiatric out-patients: associations with quality of life, functioning, hope and self-esteem. Psychiatry Res. 2016;246:500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karia SB, De Sousa A, Shah N, Sonavane S, Bharati A. Psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in skin diseases: a comparison of alopecia areata and psoriasis. Ind Psychiatry J. 2015;24(2):125–128. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.181724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zięciak T, Rzepa T, Król J, Żaba R. Feelings of stigmatization and depressive symptoms in psoriasis patients. Psychiatr Pol. 2017;51(6):1153–1163. doi: 10.12740/PP/68848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards HL, Fortune DG, Griffiths CE, Maine CJ. The contribution of perceptions of stigmatisation to disability in patients with psoriasis. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:11–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, Bowcock S, Main CJ, Griffiths CE. A cognitive-behavioural symptom management programme as an adjunct in psoriasis therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:458–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makowska I, Gmitrowicz A. Psychodermatologia—pogranicze dermatologii, psychiatrii i psychologii. Psychiatr Psychol Klin. 2014;14(2):100–105. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimitrov D, Szepietowski JC. Stigmatization in dermatology with a special focus on psoriatic patients. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2017;71:1015–1022. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0010.6879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Brakel WH, Augustine V, Ebenso B, Cross H. Review of recent literature on leprosy and stigma. Lepr Rev. 2010;81:259–264. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers E, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, Crean T. A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48(8):1042–1047. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.8.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers ES, Ralph RO, Salzer MS. Validating the empowerment scale with a multisite sample of consumers of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:933–936. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.9.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hrehorów E, Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Evers A, Ginsburg IH. Narzędzia do oceny stygmatyzacji u chorych na łuszczycę: polskie wersje językowe. Dermatol Klin. 2006;8(4):253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szepietowski J, Salomon J, Finlay AY, et al. Dermatology life quality index: Polish version. Dermatol Klin. 2004;6:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miot HA. Correlation analysis in clinical and experimental studies. J Vasc Bras. 2018;17(4):275–279. doi: 10.1590/1677-5449.174118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vardy D, Besser A, Amir M, Gesthalter B, Biton A, Buskila D. Experiences of stigmatization play a role in mediating the impact of disease severity on quality of life in psoriasis patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:736–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawro T, Janusz I, Miniszewska J, Zalewska A. Jakość życia i stygmatyzacja a nasilenie zmian skórnych i świądu u osób chorych na łuszczycę [w:] Rzepa T, Szepietowski J, Żaba R red. Psychologiczne i medyczne aspekty chorób skóry. Wrocław: Cornetis; 2011, 42–51.

- 30.Lu Y, Duller P, van der Valk PGM, Evers AWM. Helplessness as predictor of perceived stigmatization in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Psychosom. 2003;4:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Beugen S, van Middendorp H, Ferwerda M, et al. Predictors of perceived stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. BJD. 2017;176:687–694. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ograczyk A, Miniszewska J, Kępska A, Zalewska-Janowska A. Itch, disease coping strategies and quality of life in psoriasis patients. Postep Dermatol Alergol. 2014;XXXI(5):299–304. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.40927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmid-Ott G, Kuensebeck HW, Jaeger B, et al. Validity study for the stigmatization experience in atopic dermatitis and psoriatic patients. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1999;79:443–447. doi: 10.1080/000155599750009870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kent G, Keohane S. Social anxiety and disfigurement: the moderating effects of fear of negative evaluation and past experience. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001;40:23–34. doi: 10.1348/014466501163454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zachariae R, Zachariae H, Ibsen HHW, Mortensen JT, Wulf HC. Psychological symptoms and quality of life of dermatology outpatients and hospitalized dermatology patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:205–212. doi: 10.1080/00015550410023284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jankowiak B, Sekmistrz S, Kowalewska B, Niczyporuk W, Krajewska-Kułak E. Satisfaction with life in a group of psoriasis patients. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:85–90. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2013.34156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miniszewska J, Juczyński Z, Ograczyk A, Zalewska A. Health-related Quality of Life in Psoriasis: important role of personal resources. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2013;93:551–556. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kostyła M, Tabała K, Kocur J. Illness acceptance degree versus intensity of psychopathological symptoms in patients with psoriasis. Postep Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:134–139. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2013.35613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ginsburg IH, Link BG. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zimoląg I, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Influence of psoriasis on the ability to work. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2009;89:575–576. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.