Abstract

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is uncommon but potentially lethal when it is associated with systemic disorders. We report a case of odontogenic NF in a patient with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. The patient was referred on day 10 since the onset of odontogenic NF. Protective tracheostomy, local facial-cervical fasciotomy were conducted and broadspectrum antibiotics were given, subsequent serial surgical drainage and debridement were performed in theater. Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumonia were isolated. Five staged debridements were performed to the targeted anatomic regions thus reducing surgical time and blood loss. The patient survived the acute infection and received subsequent reconstruction. Cervical NF with descending mediastinitis and periorbital NF is associated with high mortality rates. This is the only known report of an adult who survived NF affecting entire scalp, periorbital, cervical, and thoracic region. Early diagnosis and staged surgical planning minimize morbidity and mortality from NF.

Keywords: Necrotizing fasciitis, Craniocervical, Soft tissue infection, Odontogenic, Diabetes mellitus

Hippocrates described necrotizing fasciitis (NF) in the 5th century [1]. Mc-Cafferty and Lyons used the term “suppurative fasciitis” in 1948, and reported that early recognition and surgical intervention result in a reduction of morbidity [2]. Wilson was the first person using the term “necrotizing fasciitis” in 1952 [3].

NF is characterized by its fulminating, devastating, rapidly-progressing, and generalized necrosis of the superficial fascial layer and the involved cutaneous tissue. NF occurs more commonly in patients with compromised immune systems, and more frequently in the abdominal wall, perineum, and extremities. Involvement of the head and neck structures, especially the scalp, is rare. In Brunworth's review, in most major medical centers, the frequency of dental infection resulting in craniocervical NF is approximately 1.2 cases per year [4]. We present a case of NF of odontogenic origin in an adult patient with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. The NF progressed rapidly and crossed multiple tissue spaces of the head and neck.

Case report

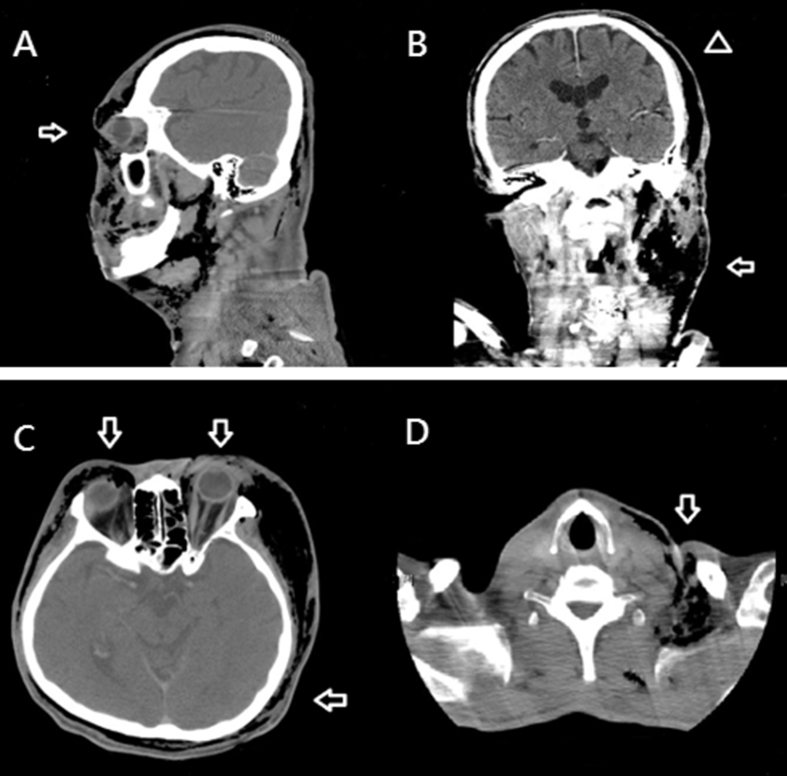

A 44-year-old male with unknown history of diabetes mellitus presented to the local hospital with 10 days history of progressive left facial necrosis and blurred vision of the left eye. It is associated with left periorbital pain, swelling, fever, and general malaise. Physical examination showed crepitus, fluctuation and local heat over entire face and scalp. The patient reported to have his left upper second decayed molar self-extracted at home 2 weeks prior to the onset of the symptoms. Besides, he has been suffering from the decayed tooth for weeks with intermittent sharp pain, poor oral hygiene and loss of appetite. He was found to be hyperglycemic (576 mg/dL plasma glucose) on presentation. Computed tomography (CT) images revealed the presence of diffuse subcutaneous emphysematous changes of the neck and left upper thorax, as well as bilateral facial, periorbital, and scalp regions [Fig. 1]. Lab data revealed leukocytosis (44400/uL), high CRP level (335 mg/L), metabolic acidosis (pH = 7.277, pCO2 = 12.8 mmHg), and high procalcitonin level (20.4 ng/mL), which indicated septic status.

Fig. 1.

The findings of necrotizing fasciitis (NF) in computed tomography. (A) Sagittal view. NF is present in the cervical, facial, periorbital, and whole scalp planes. The arrow indicates left periorbital involvement. (B) Coronal view, (Arrow) massive gas accumulated over left facial-cervical region and dissected the scalp from the left side to the right side. (Arrowhead) NF of the entire scalp. (C) Axial view, (Arrow) circumferential emphysematous change and fat-stranding indicated the extent of the NF. (D) (Arrow) Cervical descending NF.

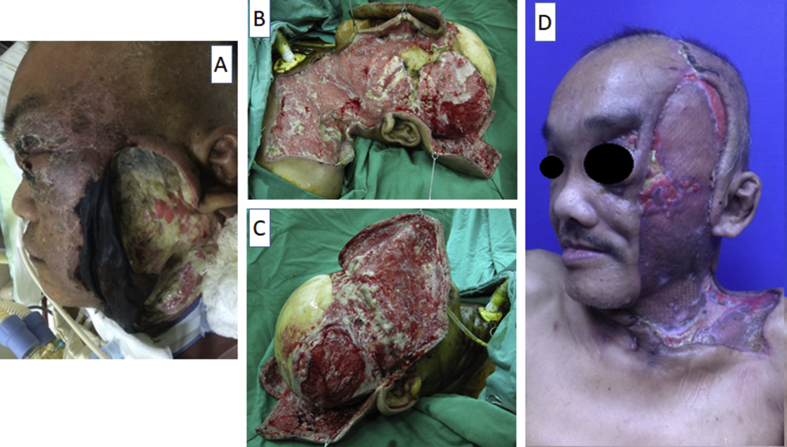

Urgent operation was organized, tracheostomy and naso-gastric tube were inserted for airway maintenance and gastric emptying, immediate surgical drainage and debridement of the necrotic left face was performed [Fig. 2A]. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit to stabilize his vital signs and hyperglycemia. Blood cultures revealed oxacillin-sensitive staphylococcus bacteremia, the septic shock was treated with oxacillin and ceftazidime.

Fig. 2.

Photos of perioperative findings. (A) Initially, left facial necrosis extending to periorbital tissue and entire scalp. (B) Elevated anterior facial and occipital flaps were used to expose the scalp fascial layers as completely as possible. (C) Right side view. (D) Left side view showed left grafted face and partial exposed zygomatic bony tissue.

Staged and targeted surgeries were planned once the conscious state improved and serum glucose level stabilized. Extensive fasciotomy and fasciectomy were firstly performed on left scalp, face, neck, and chest. The left facial flap was elevated to facilitate the debridement of necrotic tissue. A bicoronal incision was used to extend the previous incision to the right side removing all subgaleal, deep temporal fascial, and periosteal, necrotic tissue around the forehead and temple areas. The upper blepharoplasty incision was used to gain access to the periorbital space. An anterior facial flap based on the superficial temporal arteries and an occipital flap based on the occipital arteries were raised, allowing extensive fasciectomy for bacterial loading reduction [Fig. 2B, C]. Wound culture revealed the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteria, the antibiotics were changed to vancomycin and imipenem/cilastatin. In the final procedure, left medial thigh meshed split thickness skin graft was used to resurface the granulation tissue over the left head and neck region. The timeline of the admission treatment was as the following.

| (Operations) | ER |

1st |

2nd |

3rd |

4th |

5th |

6th |

7th |

8th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D0 | D1 | D9 | D15 | D20 | D22 | D26 | D30 | D37 | |

| V/S (BP)mmHg | 77/52 | 81/48 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Antibiotics | O + G | O + C | O + C | O + C | O + C | O + C | O + C | O + C | O + C |

| Operation | D + T | D | D | D | D | D | D | SG |

Abbreviation: V/S: Vital signs; ER: Emergency room; BP: Blood pressure; D0: admission day; Dno: days after admission; S: stable without inotropic agents; O: Oxacillin; G: Gentamycin; C: Ceftazidime; D: Debridement; T: Tracheostomy; SG: Skin graft).

The patient was discharged 37 days after admission. Further free tissue transfer to replace left grafted face and cover exposed bony tissue was well explained in clinic, however he refused to receive any surgical procedure [Fig. 2D]. Fortunately, his visual acuity of left eye preserved well without loss.

Discussion

Infection of second and third molars of the mandible are the most frequent aetiologies of odontogenic cervical NF [5]. Wong's study also indicated the lower molars are the most common regions [6], and Whitesides et al. revealed up to 81% of patients with cervical NF were originated from second and third molar infections [7]. These teeth deepen into the mylohyoid insertion over the lingual side of the mandible. If untreated, infection that originates from these teeth can easily extend to the submandibular space, and subsequently disseminated into surrounding spaces, including sublingual, submental, and parapharyngeal spaces. Ultimately reaches skull base with cephalad extension, or caudally into the mediastinum and thoracic cavity [8].

After the tooth extraction, the left intra-oral wound deteriorated and breached into the SMAS layer with subsequent rapid infection seeding and dissemination. The infection ultimately involved all of the fascial layers of the head and neck, including the sub-galea, the deep temporal fascia, the SMAS layer, the periorbital fascia, as well as the cervical region, extending into the left thoracic wall.

Periorbital region is a relatively uncommon location for head and neck NF [9], [10]. Amrith's review of 61 reports published over 20-year period identified 94 patients with periorbital NF. He found group A β-hemolytic streptococcus was the most common pathogen resulted in NF, constitutes 51.1% of all reported cases, and 31% of them developed toxic shock syndrome. This group had an 8.5% mortality rate and a 14% risk of permanent blindness. Factors that are associated with higher mortality rate including toxic shock syndrome (p < 0.001), facial involvement (p = 0.032), and permanent loss of vision (p = 0.035) [11]. Similarly, Golger et al. found age, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, and immune status are significant determinants of mortality from NF [12].

Head and neck infections of odontogenic origin are characterized by polymicrobial infections that consist of aerobic and anaerobic organisms. β-hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and bacteroides are the predominant infecting organisms in the oral cavity. In our case with diabetes, compatible with Cheng's study that diabetic patients with NF are more related to polymicrobial infection or Klebsiella pneumonia [13].

Appropriate radiographic studies are helpful for the diagnosis of NF. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most useful imaging modality to differentiate between necrotizing and non-necrotizing soft tissue infections [14]. Specific NF findings such as soft tissue thickening within muscles and deep fascia are highlighted on T2-weighted images. However, the association of these MRI findings with morbidity or mortality has yet to be determined. Radiographic or CT imaging evidence of subcutaneous gas produced by Enterobacteriaceae and Klebsiella, has been reported in 17%–29% of patients [15]. This finding is highly specific, but not sensitive. Wysoki et al. performed a retrospective study and revealed the presence of inflammatory changes such as abscess or fascial thickening in CT images have sensitivity of 80% for NF diagnosis. CT imaging is thus a more sensitive modality in diagnosing NF when compared with plain X-ray [16]. Sonography examination is considered to be neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis of NF, and is only appropriate to evaluate superficial abscesses.

The presence of diabetes mellitus significantly affects clinical outcomes, and is associated with longer hospital stays and a higher incidence of complications [12], [13], [17]. High serum glucose level on admission is the predominant risk factor associated with complications from multi-space infections of the head and neck [13], [17]. Zheng et al. concluded that diabetic patients have longer hospital stay compared with their non-diabetic counterparts (22 days versus 15 days, respectively); 58.5% of the diabetic patients in his study population developed complications, in contrast with 21.9% of the non-diabetic subgroup [17]. Golger et al. found 60% of patients with diabetes experience torturous clinically course with significant morbidity or mortality, compared with 29% of non-diabetic counterparts [12]. The most frequent complications are airway obstruction and descending necrotizing mediastinitis [17].

To avoid time-consuming surgeries and severe blood loss, planned and staged debridement of the affected regions should be performed after initial abscess drainage. Frequent surgical drainage and debridement are keys to good results [13], [18]. Our staged surgery that targeted different anatomic zones was designed to minimize surgical time and blood loss. The left side of the head and neck region was treated first, followed by the right side, and the occipital area. Using a bicoronal incision, we elevated the facial flap anteriorly based on the superficial temporal arteries and facial arteries, and raised the occipital flap based on the occipital arteries and the posterior auricular arteries. This approach maintains an adequate blood supply to the distantly located vital tissues and increases visualization of the necrotic tissue along the fascial layer. Blepharoplasty incisions were performed to approach the non-vital structures in the periorbital area. Identifying vital structures including facial nerve and orbital sheath with gentle tissue handling in achieving a better aesthetic and functional outcome. Temporary tarsorrhaphy is necessary for iatrogenic cicatricial lagophthalmos following serial debridements. As the patient's condition improved, subsequent scalp wound closures and split thickness skin grafts were indicated for reconstruction. This approach is life-saving, function-preserving, and cosmesis-maintaining for this patient.

Conclusion

Treating severe diffusive head and neck NF associated with hyperglycemia and septic shock is a clinical challenge and is associated with extremely high mortality rate. A practical and staged surgical plan was utilized in this case. Our approach resulted in shorter surgery times and avoided massive blood loss. In addition, this method provides an adequate pathway in reaching the optimal outcomes in survival, functional preservation, and cosmesis.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Thanks for Dr. Rami Hallac for help in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Descamps V., Aitken J., Lee M.G. Hippocrates on necrotizing fasciitis. Lancet. 1994;344:556. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCafferty E., Lyons C. Suppurative fasciitis as an essential feature of hemolytic streptococcus gangrene with notes on fasciotomy and early wound closure as treatment of choice. Surgery. 1948;24:438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Ann Surg. 1952;58:144. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunworth J., Shibuya T.Y. Craniocervical necrotizing fasciitis resulting from dentoalveolar infection. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am. 2011;23:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fliss D.M., Tovi F., Zirkin H.J. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections of dental origin. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:1104–1108. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90298-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D.Y., Huang J.S., Chung C.H., Chen H.A. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis of odontogenic origin: a report of 11 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:1347–1352. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.18259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitesides L., Cotto-Cumba C., Myers R.A.M. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis of odontogenic origin: a case report and review of 12 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:144–151. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)90327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed J.M., Anand V.K. Odontogenic cervical necrotizing fasciitis with intrathoracic extension. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:596–600. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suharwardy J. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:233–234. doi: 10.1136/bjo.78.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazzeri D., Lazzeri S., Figus M., Tascini C., Bocci G., Colizzi L. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis. 2010;94:1577–1585. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.167486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amrith S., Hosdurga Pai V., Ling W.W. Periorbital necrotizing fasciitis–a review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:596–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golger A., Ching S., Goldsmith C.H., Pennie R.A., Bain J.R. Mortality in patients with necrotizing fasciitis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1803–1807. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000259040.71478.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng N.C., Tai H.C., Chang S.C., Chang C.H., Lai H.S. Necrotizing fasciitis in patients with diabetes mellitus: clinical characteristics and risk factors for mortality. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1144-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edlich R.F., Cross C.L., Dahlstrom J.J., Long W.B. Modern concepts of the diagnosis and treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McHenry C.R., Piotrowski J.J., Petrinic D., Malangoni M.A. Determinants of mortality for necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Ann Surg. 1995;221:558. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199505000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wysoki M.G., Santora T.A., Shah R.M., Friedman A.C. Necrotizing fasciitis: CT characteristics. Radiology. 1997;203:859–863. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng L., Yang C., Zhang W., Cai X., Kim E., Jiang B. Is there association between severe multispace infections of the oral maxillofacial region and diabetes mellitus? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:1565–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakamoto H., Aoki T., Kise Y., Watanabe D., Sasaki J. Descending necrotizing mediastinitis due to odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:412–419. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]