Abstract

Asthma is a chronic disease that has a significant impact on quality of life and is particularly important in children and adolescents, in part due to the higher incidence of allergies in children. The incidence of asthma has increased dramatically during this time period, with the highest increases in the urban areas of developed countries. It seems that the incidence in developing countries may follow this trend as well. While our knowledge of the pathophysiology of asthma and the available of newer, safer medication have both improved, the mortality of the disease has undergone an overall increase in the past 30 years. Asthma treatment goals in children include decreasing mortality and improving quality of life. Specific treatment goals include but are not limited to decreasing inflammation, improving lung function, decreasing clinical symptoms, reducing hospital stays and emergency department visits, reducing work or school absences, and reducing the need for rescue medications. Non-pharmacological management strategies include allergen avoidance, environmental evaluation for allergens and irritants, patient education, allergy testing, regular monitoring of lung function, and the use of asthma management plans, asthma control tests, peak flow meters, and asthma diaries. Achieving asthma treatment goals reduces direct and indirect costs of asthma and is economically cost-effective. Treatment in children presents unique challenges in diagnosis and management. Challenges in diagnosis include consideration of other diseases such as viral respiratory illnesses or vocal cord dysfunction. Challenges in management include evaluation of the child’s ability to use inhalers and peak flow meters and the management of exercise-induced asthma.

Keywords: Asthma, Allergies, Exercise-induced asthma, Pediatric asthma, Atopic march, Wheezing, Viral respiratory infections

Introduction

The incidence of allergies and asthma in the Western world has been increasing over the past 30 years. However, more recent data suggest that over the past 5–10 years, the overall global trends of asthma incidence have begun to stabilize [1]. Urbanization and industrialization has contributed to the increase in developed countries, but the reasons for this are still unclear. Asthma is estimated to be responsible for one in every 250 deaths worldwide. Many of these deaths are preventable, and specific issues have been identified that may contribute to this high mortality rate. Factors that contribute to high mortality and morbidity include slow access to care and medications, inadequate environmental control of allergens and irritants, dietary changes, genetic variations, cultural barriers, lack of education among patients and providers, insufficient resources, and improper use of health care dollars.

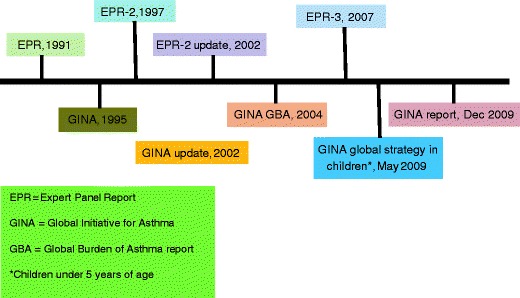

The Global Initiative for Asthma, initiated in 1989 for the World Health Organization and the US National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) periodically establish guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma [2–4]. The most recent significant update to these recommendations appeared in the Expert Panel Review 3 (EPR-3) published by the National Education for Asthma Prevention Program (NAEPP) coordinating committee of the NHLBI of the NIH [4]. A historical timeline of these revisions is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Historical chart showing recommendations in asthma treatment worldwide

The development of newer medications and delivery devices over the past 25 years has made a significant impact on our ability to decrease morbidity of childhood asthma. Hospitalizations for asthma have clearly decreased as a result of the use of controller medications. Quality of life has been identified as a significant metric to measure asthma treatment success. On the other hand, despite our improved knowledge of the pathogenesis of asthma, newer medications with fewer adverse effects, and increased standardization of treatment protocols, there has been a paradoxical increase in asthma mortality. The reasons for this observation are debatable but may include lifestyle changes [5], dietary changes [6], the increase in obesity rates in the Western hemisphere [7], coding anomalies [8], poor patient and/or caregiver education, and the overall increase in the incidence of allergies and asthma. What is clear, however, is that the development and introduction of new pharmaceuticals is not by itself the answer to improving outcomes in children with asthma. Patient education, environmental avoidance measures, proper use of medications, and immunotherapy are all equally important in the successful treatment of the pediatric asthmatic. The good news is that with our awareness of these factors, mortality has at least stabilized over the past 5 years.

Asthma in children has a unique set of characteristics the merit discussion (Table 1). The diagnosis of asthma in children may be difficult to make in the infant because of the prevalence of viral-associated wheezing in this age group of patients. The impact of viral illness on the development of asthma in later years is addressed below, along with the role of allergies in childhood asthma. Certain medications are not always appropriate for all ages, and devices that are used to evaluate asthma status may not be usable by young children. Exercise-induced asthma (EIA) is particularly important in childhood as physical activity is critical to controlling the epidemic of obesity in developed countries, especially the USA. Lifestyle changes, including the use of television, Internet, and other video devices, may play a role in childhood asthma. Finally, the “hygiene hypothesis” has introduced the concept that early exposure to animals, foods, or endotoxin may actually be protective against allergic sensitization. While this is still a controversial issue, it illustrates the complexity of asthma as a heterogeneous disease, with genetic and environmental influences. Indeed, we now know that there is no single asthma gene, rather that there are multiple genetic variants that, under the proper environmental conditions, can result in asthma.

Table 1.

Special considerations for asthma in children

| The increased significance of allergies in childhood asthma |

| The role of passive smoking (ETS exposure) in infancy and pregnancy in the development of asthma |

| The role of RSV and other viral bronchiolitis in pediatric asthma |

| Genetics (host factors) versus environmental exposures in childhood asthma |

| Vocal cord dysfunction in teenage athletes with or without concurrent asthma |

| The increase in obesity in children and its impact on childhood asthma |

| Gender predisposition for asthma in children is reversed that in adults |

| Availability of asthma medications and indications in the pediatric age group |

| The role of immunotherapy in the very young child |

| The use of biologics in children (omalizumab and new drugs) |

| Corticosteroids and growth retardation |

| Exercise-induced asthma and sports in children |

Epidemiology and the Prevalence of Childhood Asthma

The prevalence of asthma is now estimated to be more than 300 million worldwide, or about 5% of the global population. The incidence of asthma has been steadily increasing since the 1970s, with the greatest increase occurring in modern, developed countries. Asthma accounts for about one in every 250 deaths worldwide. The national prevalence of asthma in different countries varies between 1% and 19% (Table 2). It has been observed that developed countries have the higher incidences, while third world countries have the lower rates, but in recent years, the gap is decreasing due to an increasing incidence of asthma in Asia, South America, and Africa.

Table 2.

Asthma prevalence by country (selected countries)

| Country | Prevalence (% population) |

|---|---|

| Scotland | 18.5 |

| Wales | 16.8 |

| England | 15.3 |

| New Zealand | 15.1 |

| Australia | 14.7 |

| Republic of Ireland | 14.6 |

| Canada | 14.1 |

| Peru | 13.0 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 12.6 |

| Costa Rico | 11.9 |

| Brazil | 11.4 |

| United States | 10.9 |

| Fiji | 10.5 |

| Paraguay | 9.7 |

| Uruguay | 9.5 |

| Israel | 9.0 |

| Panama | 8.8 |

| Kuwait | 8.5 |

| Ukraine | 8.3 |

| Ecuador | 8.2 |

| South Africa | 8.1 |

| Finland | 8.0 |

| Czech Republic | 8.0 |

| Columbia | 7.4 |

| Turkey | 7.4 |

| Germany | 6.9 |

| France | 6.8 |

| Norway | 6.8 |

| Japan | 6.7 |

| Hong Kong | 6.2 |

| United Arab Emirates | 6.2 |

| Spain | 5.7 |

| Saudi Arabia | 5.6 |

| Argentina | 5.5 |

| Chile | 5.1 |

| Italy | 4.5 |

| South Korea | 3.9 |

| Mexico | 3.3 |

| Denmark | 3.0 |

| India | 3.0 |

| Cyprus | 2.4 |

| Switzerland | 2.3 |

| Russia | 2.2 |

| China | 2.1 |

| Greece | 1.9 |

| Georgia | 1.8 |

| Romania | 1.5 |

| Albania | 1.3 |

| Indonesia | 1.1 |

The gender predominance is reversed in children from that in adults. In children under the age of 14, there is a 2:1 male-to-female prevalence of asthma, approximately opposite that in adults. Obesity appears to be a risk factor for asthma. Diet is more complicated, and the initial observation that breast feeding protects against asthma is being challenged. Exposure to Western diets comprising high levels of processed foods with increased levels of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, decreased antioxidant levels, and decreased n3-polyunsaturated fatty acids has been associated with the increase in asthma and allergies observed over the past few decades.

Genetics and Asthma

Asthma is heritable. Children born to asthmatic parents have an increased chance of developing asthma as well. Asthma is polygenic, and multiple phenotypes exist. It is estimated that up to 70% of asthma in children is associated with atopy, or allergies. Airway hyperresponsiveness, serum IgE levels, inflammatory mediator expression, and Th1/Th2 balance are four areas that may be influenced by genetics. The genes involved in regulating these processes may differ between ethnic groups. Some of these processes, such as airway hyperresponsiveness and serum IgE levels, may be co-inherited in some individuals, possibly as a result of close proximity of genes affecting both processes (chromosome 5q).

Genes can also affect an asthmatic child’s response to medications. This has been found to be the case for β-adrenergic agonists, glucocorticoids, and leukotriene modifiers. While studies of pharmacogenetics have so far produced more questions than answers, this is an exciting area of research because it promises the capability of generating customized care plans, or personalized medicine, that will match optimal treatment with each individual asthmatic child. Genes that are involved in asthma are now too numerous to count. An example of genes associated with asthma is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

A few selected candidate genes for asthma and their impact on disease or treatment

| Gene | Target response/asthma phenotype | Population/location |

|---|---|---|

| CTLA-4 [9] | Response to corticosteroids | European |

| Arginase 1 and 2 [10] | Response to bronchodilators | The Netherlands |

| Glutathione S-transferase [11, 12] | With air pollution as interactive risk factors | Italy |

| ADAM-33 [13] | Risk for asthma, elevated IgE and increased specific IgE to dust mite species | Columbia |

| IL-4R [14] | Specific asthma phenotype, eczema and allergic rhinitis | Sweden |

| DENNB1B [15] | Increased susceptibility to asthma (GWAS study) | North America |

| LTA4H and AOX5AP [16] | Gene–gene interactions convey variants in asthma susceptibility | Latinos (Mexico and Puerto Rico) |

| TLR4 [17] | Gene polymorphisms convey risk of asthma (IRAK1, NOD1, MAP3K7IP1 gene–gene interactions) | The Netherlands |

| PHF11 and DPP10 [18] | Risk for asthma | Chinese, European, and Latin American |

| NOS1 [19] | Increased IgE levels, increase in frequency of asthma phenotype | Taiwanese |

| ECP [20] | Allergy and asthma symptoms, smoking | From the European Community Respiratory Health Survey |

| TSLP [21] | Higher risk of childhood and adult asthma | Japan |

| RANTES [22] | Higher risk of asthma in subgroup analysis by atopic status | Global |

TLR Toll-like receptor, PHF11 plant homeodomain zinc finger protein 11, DPP10 dipeptidyl-peptidase 10, ADAM-33 a disintegrin and metalloprotein 33, LTA4H leukotriene A (4) hydrolase, ALOX5AP arachidonate 5 lipooxygenase activating protein, IL-4R interleukin 4 receptor, CTLA-4 cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4, NOS-1 nitric oxide synthase 1, ECP eosinophilic cationic protein, TSLP thymic stromal lymphopoietin, RANTES regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed, and secreted, GWAS genome-wide associations studies

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Childhood Asthma

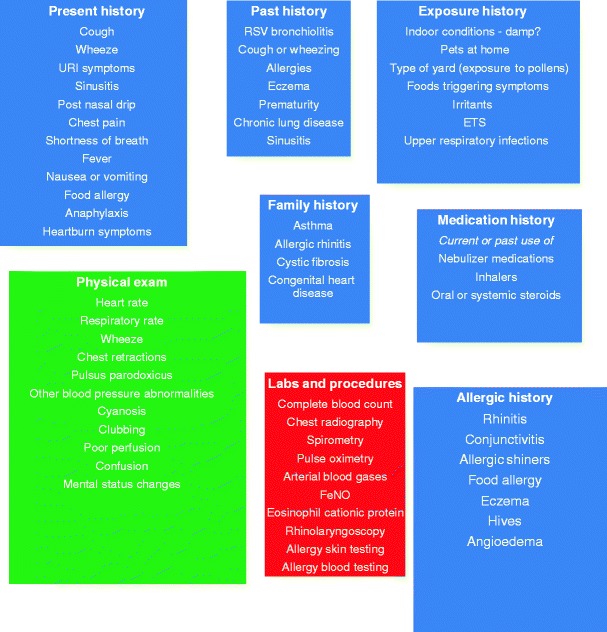

Making the diagnosis of childhood asthma requires taking a thorough history and doing a complete physical examination on the patient. There are many conditions which may mimic asthma. Some of these diagnoses are age dependent. A complete list of conditions in the differential diagnosis is shown in Table 4. Asthma is still a clinical diagnosis, as there is no pathognomonic marker for diagnosing asthma. Taking a good history is critical. A good history includes current or past history of cough, wheezing, viral respiratory diseases, accompanying allergy symptoms or signs, shortness of breath, and sinus problems. It is also important to ask an exposure history, to try and determine triggers for the episodes. This can include indoor allergen exposures, outdoor pollens, viral upper respiratory infections and exercise, exposure to foods that may be causing symptoms, and an occupational history of both the child (if old enough to be working) and the parents or caregivers. Exposure to day care is also important and environmental tobacco smoke and pollution exposure should also be documented. A past medical history asking about previous hospitalizations, doctor visits, frequent otitis media, sinusitis or pneumonia, and a complete medication history, including use of nebulizers or inhalers and any other pertinent medications, should be elicited. The family history is also important, as asthma has a genetic component.

Table 4.

Differential diagnosis of cough, wheezing, and other bronchial sounds

| Asthma |

| Foreign body aspiration |

| Aspiration pneumonia |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| Heart disease |

| Infections (may be viral, bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial) |

| Pneumonia |

| Bronchitis |

| Bronchiolitis |

| Epiglottitis (stridor, respiratory distress) |

| Sinusitis |

| Exposures |

| Allergies |

| Smoke inhalation |

| Toxic inhalations |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis |

| Gastroesophageal reflux |

| Genetic disorders |

| Cystic fibrosis |

| Iatrogenic |

| ACE inhibitor-related cough |

| Anatomical abnormalities |

| Vocal cord dysfunction |

| Vocal cord anomalies (nodules) |

| Subglottic stenosis (stridor) |

| Laryngotracheal malacia (in infants) |

| Vascular anomalies of the chest |

| Endotracheal fistulas and tracheal anomalies |

| Other |

| Immunodeficiency syndromes |

| Obesity |

In addition to taking a good history, a complete physical examination should also be conducted to rule out any other possible diagnoses. The intensity and characteristics of any breathing sounds should be determined. While the presence of a wheeze may suggest asthma, foreign body aspiration may also be a possibility if the wheeze is unilateral. The presence of a heart murmur may suggest a coarctation with compression of the trachea. Clubbing of the fingers may be suggested of a more chronic condition such as cystic fibrosis. These are only some of the many observations one may glean from a physical examination that can help in establishing or ruling out the diagnosis of asthma.

Procedures and laboratory tests have a role in the diagnosis of asthma. Allergy testing may be indicated if the history is consistent with an allergic component or trigger. Spirometry should certainly be done, with the response to bronchodilators examined as well. Exercise challenge tests can be done in the child or adolescent who suspects exercise-induced asthma or bronchospasm. Other tests that may be helpful in monitoring the condition of an asthmatic may be fractional inhaled nitric oxide. A complete blood count, chest X-ray, or sinus CT scan may also be indicated in some cases. Components of a diagnostic scheme and clinical assessment of asthma are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Diagnosis and clinical assessment of the asthmatic child—the appropriate parts of the history and physical examination should be performed depending on the circumstances (e.g., is this a new patient with a history of cough presenting to the office as a consult, or is this a patients with known asthma who is in the midst of an asthma exacerbation presenting to the emergency room)

While we think of wheezing as a hallmark of asthma, it can be present in children without asthma and absent in those with asthma. In children under 5 years of age, wheezing can be categorized into three groups: transient early wheezing, persistent early-onset wheezing, and late-onset wheezing/asthma. These are discussed in more detail below.

Triggers of Asthma in Children

Allergens

It is estimated that between 60% and 70% of asthma in children is allergic asthma. Conversely, children with allergies have a 30% chance of having asthma as well. The atopic march describes a commonly seen paradigm in which children who are atopic (genetically predisposed to developing allergies) present early in life with atopic dermatitis, then asthma, and finally allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis. Common allergens can be categorized into either indoor or outdoor allergens. The outdoor allergens are mostly linked to seasonal allergic rhinitis, while indoor allergens are linked to perennial allergic rhinitis. There are geographical differences in the seasonal distribution of pollen allergens. Recently, it has been suggested that climate change may be impacting the prevalence of various outdoor allergens through different mechanisms. In addition, environmental exposures and host factors can lead to changes in an individual’s sensitivities throughout life. Certain allergens, such as dust mite, cat and dog dander, and Aspergillus, are independent risk factors for the development of symptoms of asthma in children under 3 years of age [23].

On the other hand, the “hygiene hypothesis” has been used to explain why in some cases exposure to dogs and/or cats leads to a decrease in allergic sensitization [24]. These inconsistencies in studies on allergen sensitivity have not been adequately resolved, and it is likely that other factors, possibly related to the timing of exposure or host factors, play a significant role in the effect of allergen exposure on sensitization. In addition to cats and dogs, other pets such as guinea pig, gerbils, hamsters, mice, rats, and rabbits can also trigger asthma attacks in susceptible individuals.

It has been suggested that exposure to endotoxin may play a protective role in allergen sensitization, though this is not universally observed. Cockroach and mouse allergen have both been found to play a significant role in allergic sensitization in children living in inner city environments [25]. Both early- and late-phase reactions have occurred in places where cockroach infestation is a problem, such as highly populated urban areas in warm climates.

Food allergens can be a significant cause of allergic sensitization in children, especially in the younger age range. Foods are typically associated with eczema in infants and toddlers, but eczema is a feature of atopy and the earliest manifestation of the “atopic march.” These patients can subsequently develop asthma or allergic rhinoconjunctivitis as they grow older.

In order to treat allergic asthma effectively, it is therefore important to identify a child’s current allergic sensitization patterns. This can be done by skin testing or by a blood test that measures specific IgE. There are advantages and disadvantages to both forms of testing. Skin testing is more sensitive and specific, although the blood test methodology is improving. The blood test can be done if there are contraindications to skin testing, such as in the very young child who may not be able to tolerate skin testing, a patient on antihistamines or β-blockers, or a patient with a severe rash. Available now are “multi-test” devices that facilitate skin testing and make it possible to perform in the very young child. A list of common environmental allergens is shown in Table 5. While food allergens can also trigger asthma, these are less likely triggers, and testing for food allergens is not as sensitive or specific as environmental allergens.

Table 5.

Common allergenic determinants

| Determinant | Source | Source scientific name | Protein class/function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Der p 1 | Dust mite | Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus | Cysteine protease |

| Der p 2 | Dust mite | Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus | Serine protease |

| Der f 1 | Dust mite | Dermatophagoides farina | Cysteine protease |

| Der f 2 | Dust mite | Dermatophagoides farina | Serine protease |

| Der m 1 | Dust mite | Dermatophagoides microcerax | Cysteine protease |

| Blo t 1 | Dust mite | Blomia tropicalis | Cysteine protease |

| Fel d 1 | Cat | Felis domesticus | Salivary glycoprotein |

| Can f 1 | Dog | Canis familiaris | Salivary lipocalin proteins |

| Bla g 1 | Cockroach | Blatella germanica | Unknown |

| Bla g 2 | Cockroach | Blatella germanica | Aspartic proteinase |

| Rat n 1 | Rat | Rattus norvegicus | Major urinary protein |

| Mus m 1 | Mouse | Mus muscularis | Major urinary protein |

| Per a 7 | Cockroach | Periplaneta americana | Tropomyosin |

| Lol p 1 | Ryegrass | Lolium perenne | Unknown |

| Amb a 1 | Ragweed | Ambrosia artemistifolia | Polysaccharide lyase 1 family |

| Aln g 1 | Alder | Alnus glutinosa | Pathogenesis-related protein |

| Bet v 1 | Birch | Betula verrucosa | Pathogenesis-related protein |

| Que a 1 | Oak | Quercus alba | Pathogenesis-related protein |

| Ole e 1 | Olive | Olea europea | Unknown |

| Cyn d 1 | Bermuda grass | Cynodon dactylon | Expansin family |

| Art v 1 | Mugwort | Artemisia vulgaris | Unknown |

| Dac g 3 | Orchard grass | Datylus glomerata | Expansin family |

Irritants

Most air pollutants are irritants, although some can have immunomodulatory effects. The most extensively studied airborne pollutant is environmental cigarette smoke. Gaseous irritants include nitric oxide, sulfur dioxide, formaldehyde, ozone, and other volatile organic compounds. Airborne particulates can vary in size, ranging from course particulates to fine particles to ultrafine particles or nanoparticles. The smaller the particle, the greater the penetration into the airway. Particles greater than 10 μm in diameter are generally cleared in the upper airway. Although these larger particles can indirectly trigger early- or late-phase asthma reactions by virtue of their action in the upper airways, fine and ultrafine particles present a more significant problem due to their deeper penetration into the smaller airways [26]. Recently, evidence has surfaced that these ultrafine particles indeed possess effects on inflammatory cells such as neutrophils or eosinophils that can lead to asthma symptoms. This can occur through several different mechanisms and is reviewed extensively elsewhere [26].

Exercise-Induced Asthma or Bronchospasm

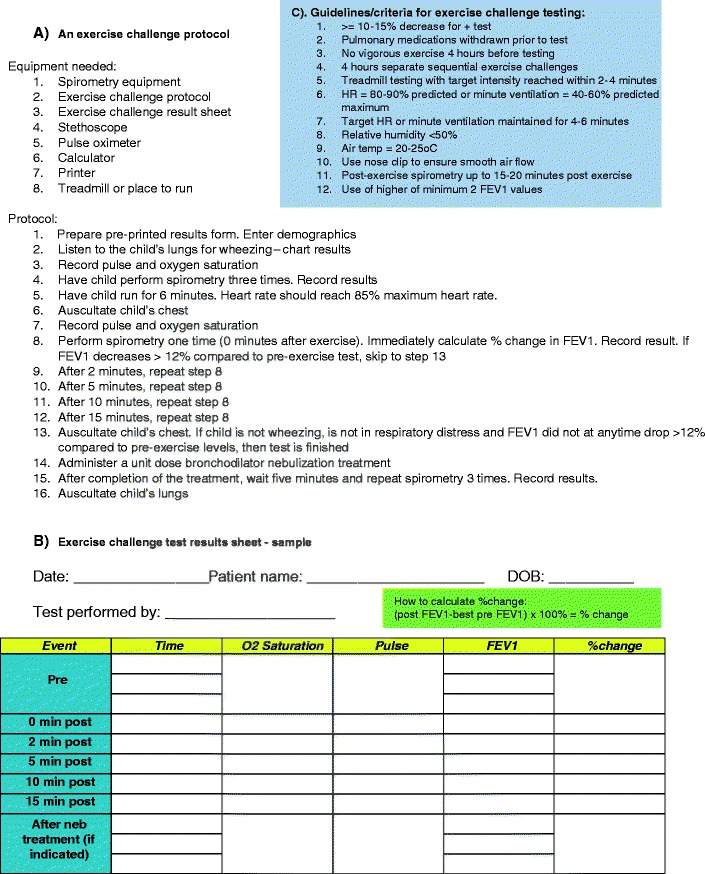

Exercise is a common trigger for asthma in children [27]. However, exercise is essential to the physical and psychological development of all children. Lack of exercise also promotes obesity, which has been linked to asthma [28]. Therefore, we no longer recommend that children with asthma stop exercising. In fact, exercise can help to build lung reserve. With proper control of asthma using controller medications, a patient with exercise-induced asthma can almost always participate in regular cardiovascular training without adverse effects. Asthma can even be managed successfully in the elite athlete [29]. The severity of a patient’s EIA can be evaluated using an exercise challenge test. Historically, the methodology of exercise challenge tests has been very inconsistent, but recently the American Thoracic Society has proposed a set of criteria that should be met in order to ensure an accurate and valid test [30]. These criteria and a typical protocol are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

a An exercise challenge protocol. b Exercise challenge test results sheet—sample. c Guidelines/criteria for exercise challenge testing

Viral Respiratory Illness and Asthma

The link between viral respiratory infections and asthma has been well established [31–33]. In infants, the most well-known viral respiratory illness associated with wheezing is respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). However, rhinovirus is the more common virus in children [34, 35], and wheezing can be associated with other viruses as well, including parainfluenza virus, influenza virus, metapneumonia virus, adenovirus, coronavirus, and picornavirus. Rhinovirus is the major pathogen associated with hospital admissions for asthma in children [36].

Transient early wheezing develops in infancy and usually resolves by 3 years of age. Risk factors include low birth weight, prematurity, maternal exposure to tobacco smoke, male gender, and upper respiratory viral infections. A second phenotype is that of the atopic wheezer. These are school age children who have a history or family history of atopy. Their wheezing may or may not be triggered by a viral infection, but they have a strong probability of continued wheezing into adolescence or adulthood. It is in this group that one would be able to detect chronic inflammatory changes in the airways. A third category, persistent early-onset wheezing, includes pre-school aged children and is usually not associated with a family history of asthma or atopy but instead is associated with acute viral respiratory infections. This group has a better long-term prognosis and symptoms may disappear when they reach school age.

Bronchiolitis in infancy can lead to decreased FEV1 and FEF25–75% in childhood [37]. A connection between asthma and RSV bronchiolitis was supported by an observation that there is elevated ECP and leukotriene C4 in the nasal lavage fluid of infants with RSV bronchiolitis [38]. It is not clear whether the occurrence of RSV bronchiolitis as an infant significantly increases the risk of developing asthma at a later age, although one prospective study of 47 children hospitalized for RSV bronchiolitis in infancy showed a higher incidence of airway hyperreactivity at age 13 compared to 93 matched controls [39]. Continued follow-up of these patients revealed a persistent increase in allergic asthma into early adulthood among patients who had RSV bronchiolitis in infancy [40].

Interpreting the New Asthma Guidelines in Children

The new EPR guidelines were released in 2007 [4]. These guidelines contain revisions that were aimed at improving the overall care of asthmatics. There are several important changes. Firstly, the main goal of asthma treatment is control of symptoms and disease. A list of specific goals to target control is shown in Table 6. Better distinction is made between monitoring asthma control and classifying asthma severity. Severity is defined as the intrinsic intensity of asthma and is still grouped into the original classification of mild intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent, or severe persistent. Categorizing severity in this manner is helpful for initiating therapy. Control is defined as the response to therapy, in terms of the degree to which manifestations of asthma are kept to a minimum. Therapy should be adjusted periodically in order to maintain control.

Table 6.

Treatment goals in asthma

| Decreasing mortality |

| Decreasing morbidity and improving quality of life |

| Fewer nighttime awakenings |

| Ability to participate in sports with no limitations |

| Fewer school or work days lost |

| Reduction of symptoms of cough or wheezing |

| Reduction in the need for rescue medications |

| Easy compliance with medications with minimal disruptions in daily life |

| Reduction in side effects of asthma medications |

| Reduction in the number and severity of asthma exacerbations |

| Reduction in emergency or unscheduled office or clinic visits |

| Reduction in the need for systemic steroids |

| Prevention of “airway remodeling” and long-term sequelae of asthma |

| Economic goals |

| Reducing costs of treating asthma by improving preventative measures |

The second major change is the focus on impairment and risk. These are the two key domains of control and severity and provide additional information or parameters to assess response to treatment. Impairment is defined as the extent to which standard goals of asthma treatment are maintained, so this includes the frequency and intensity of symptoms and interference with good quality of life, such as an inability to conduct normal daily activities. Risk can include several parameters—the likelihood of developing an asthma exacerbation, the risk of side effects of medications, and the risk of declining lung function or lung growth.

In order to address the change in focus, the treatment recommendations have also been adjusted. The stepwise approach is still utilized, but now there are six steps, with clearly defined actions, instead of having progressive actions within each step. The treatment recommendations have also been divided into three groups depending on age, a group for children 0–4 years of age, another group addressing children 5–11 years of age, and the third group consisting of adults and children 12 and over. This was done because the evidence for the various treatment modalities may be different between age groups.

Other important recommendations address environmental control, with the recommendation for these actions being present in all age groups. Inhaled corticosteroids are the first-line control drug for all ages. The use of combination inhaled steroid and long-acting β-agonists is considered an equal alternative to increasing the dose of inhaled corticosteroids in patients 5 years of age and older, although the FDA has recently issued a black box warning on the use of long-acting beta agonists. Omalizumab is also recommended in patients with allergic asthma who are 12 years of age and older who require step 5 or 6 therapy. A black box warning for anaphylaxis accompanies omalizumab. The breakdown of the stepwise approach for children under 12 is shown in Tables 7 and 8.

Table 7.

EPR-3 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in children (0–4 years of age)

The above table was adapted from NAEPP EPR-3 guidelines [4]

Table 8.

EPR-3 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in children (5–11 years of age)

The above table was adapted from NAEPP EPR-3 guidelines [4]

Non-pharmacologic Management of Childhood Asthma

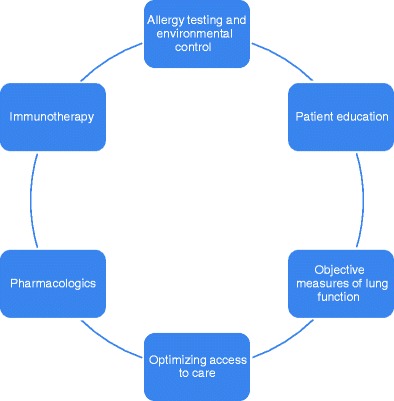

An asthma management plan involves approaching the problem from three different angles—environmental control, pharmacologic intervention, and immunotherapy. In addition, objective measurement of asthma status is important, and ongoing monitoring is also of benefit. It is clear that the development of new drugs is only a part of a more comprehensive strategy to treat asthma. In addition to drugs, non-pharmaceutical modes of treatment need to be incorporated into the asthmatic child’s treatment plan. Non-pharmaceutical modes of therapy for asthma are discussed below and listed in Table 9.

Table 9.

Ancillary treatment modalities of asthma

| Objective measurement of asthma status |

| Peak flow monitoring |

| Pulmonary function testing |

| Spirometry |

| Environmental control and identifying sensitivities |

| Allergy skin testing |

| Environmental exposure assessment |

| Allergen avoidance |

| Monitoring and prevention |

| Asthma diary sheets |

| Asthma action or management plans |

| Education |

| Asthma education |

| Exercise regimen |

| Asthma camps for children |

| Dietary assessment |

| Tobacco prevention counseling for parents |

| Internet |

| Printed material |

| Special help for children |

| Use of spacer devices |

| Small volume nebulizer machines |

Environmental Control

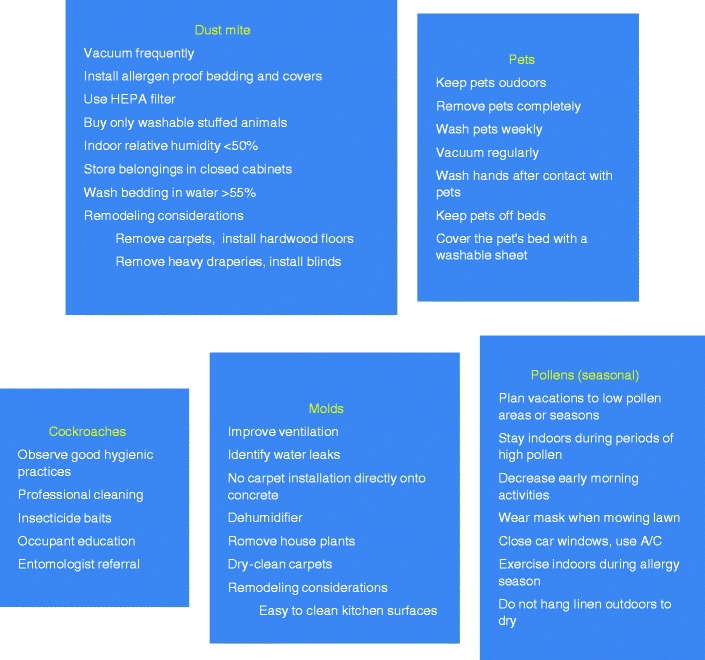

Allergen challenge studies have shown that exposure to an allergen to which an asthmatic has been sensitized is likely to bring about an asthma exacerbation [41–43]. Conversely, avoidance of such allergens may lead to resolution of the exacerbation. Thus, allergen avoidance has been recognized as an important part of an asthma management plan. The effectiveness of an allergen avoidance plan requires knowledge of the patient’s sensitivities and exposure pattern.

Avoidance of seasonal allergens, mainly pollens, is difficult without making unreasonable changes to one’s lifestyle because these allergens are windborne and can travel for miles. On the other hand, there are well-established strategies to avoidance of indoor allergens. Because we spend up to a third of our time sleeping in close quarters with dust mites, the bedroom should have a high priority when developing an indoor allergen avoidance program. Dust mites require water to survive, and damp environments allow them to reproduce and proliferate. Keeping the relative humidity of the home around 50–55% will help keep dust mite concentrations down. In addition, the use of mattress and pillow encasings, high-efficiency particulate air filters are additional control measures that may provide benefit. The child with asthma should also probably not be the one to vacuum as the action of vacuuming can disturb dust mite reservoirs and release these particulates into the breathing zone. Good ventilation and filtration systems in the home can also help to reduce exposure. Additional measures of allergen avoidance are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Avoidance measures for common allergens

Avoidance of pet allergen is best accomplished by getting rid of the pet altogether. This is often an insurmountable task because of the emotional attachment that patients, especially children, have toward their pets. If getting rid of the pet is not possible, then at least keeping the pet out of the bedroom may help. Washing the pet regularly is of questionable benefit. Numerous “denaturing” preparations are also available, but again, their effectiveness is controversial.

Molds are common allergens that originate from the outdoor environment and are particularly prevalent in moist climates. The presence of a high indoor to outdoor mold count ratio is probably indicative of a water leak or at least of excessive humidity indoors. As in the case of dust mites, keeping the relative humidity of the indoor environment at around 50% helps to reduce mold spore exposure. Substrates for mold growth include decaying living material, damp paper or books, or household plants. Removal of these substrates may reduce indoor mold spore levels.

As mentioned above, pollens are more difficult to avoid, but patients and their parents can glean information regarding outdoor exposures by accessing the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology National Allergy Bureau website (see Table 22). The site contains information on pollen and mold counts derived from counting stations run by certified counters. As of Oct 2010, there were 85 counting stations throughout the USA, as well as two in Canada and two in Argentina.

Table 22.

Asthma resources for physicians, patients and parents

| World Allergy Organization | www.worldallergy.org |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology | www.aaaai.org |

| American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology | www.aaaai.org |

| World Health Organization | www.who.org |

| American Lung Association | www.lungusa.org |

| American Thoracic Society | www.thoracic.orgg |

| Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America | www.aafa.org |

| National Technical Information Service | www.ntis.gov |

| National Asthma Education and Prevention Program | www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/naepp/ |

| National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute | www.nhlbi.nih.gov |

| Allergy and Asthma Network/Mothers of Asthmatics | www.aanma.org |

| Center for Disease Control | www.cdc.gov |

| Global Initiative for Asthma | www.ginaasthma.com |

| National Allergy Bureau | http://pollen.aaaai.org/nab/ |

| Kidshealth | www.kidshealth.org |

Spirometry in Children

Spirometry provides information on lung mechanics. Forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), the FEV1/FVC ratio, and peak expiratory flow (PEF) are the four main parameters measured during spirometry. Measurement of spirometry before and after bronchodilation treatment can help determine if there is reversibility of lung function. Because sometimes patient history, especially in children, can be inaccurate, spirometry provides an objective assessment of the child’s condition. Spirometry can be attempted at about 4 to 5 years of age, but at these very young ages, obtaining reliable results depends on the child’s ability to follow instructions and their physical coordination. Data on predicted values of spirometry parameters have been obtained by several investigators and are dependent on age, gender, height, and ethnic background. However, as in the case of peak flow measurement, there is significant individual variability, and it is important to establish each child’s baseline spirometry. Obviously, as the child grows, this will change, so frequent updates may be needed. While spirometry is not diagnostic of asthma, it serves as a complementary test to the history and physical that can be used to support the diagnosis of asthma.

The Use of Peak Flow Meters in Childhood Asthma

Measurement of peak flow should be part of an asthma management plan. Peak flow measurements provide objective evaluation of an asthmatic’s condition. With the proper teaching, even a 5-year old can learn to use a peak flow meter effectively (Fig. 5). Usually, peak flow measurements are done in the morning and in the evening, but the peak flow meter can be used throughout the day or night, whenever necessary. Most new peak flow meters are small enough to fit in a pocket or a purse. Traditional peak flow meters are available for children and adults. The low range peak flow meters usually measure up to about 450 l/m, while the high range measure up to 800 l/m. The peak flow zonal system, based on the child’s personal best peak flow, is a convenient and simple method for parents and patients to assess how they are doing, whether to administer a breathing treatment, and whether to seek additional help. Electronic versions of peak flow meters are also available. These have the advantage of being able to record and store data that can be analyzed and trended on a computer. Some of the newer electronic versions can also measure FEV1, which is considered to be a more reliable measurement of airway obstruction as it is not as dependent on patient technique or effort. An assortment of peak flow meters and spacers is shown in Fig. 6.

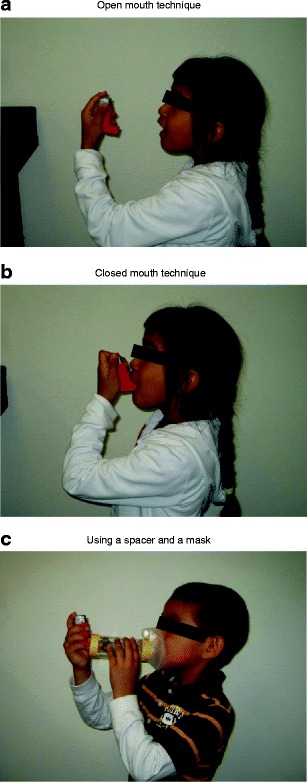

Fig. 5.

Inhaler technique. a Open mouth technique. b Closed mouth technique. c Using a spacer and a mask

Fig. 6.

A sampling of peak flow meters and spacer devices. Clockwise from upper left Aerochamber Plus spacer device, Pocket Peak peak flow meter, Aerochamber with mask, Truzone peak flow meter, Airwatch electronic peak flow meter, Piko-1 electronic lung health meter, Personal Best adult range peak flow meter

Asthma Diary Sheets and Asthma Assessment Questionnaires

Asthma diary sheets (illustrated in Fig. 7) provide patients with a means to keep track of their symptoms and their peak flows. The recent availability of electronic peak flow meters with memory is an alternative way to monitor a patient’s asthma status, which is similar to monitoring blood pressure with an automatic blood pressure cuff or diabetes with a home glucose monitoring kit. Monitoring of peak flows not only gives a continuous assessment of the patient’s condition but also may help as a reminder for patients to take their control medications, thus improving compliance. Patients should be instructed to bring their asthma diary sheets to their doctor visit, so that their progress can be reviewed. Besides symptoms and peak flows, there is space to record other pertinent information, such as β-agonist use, exposures that are out of the ordinary, addition of new medications, etc.

Fig. 7.

An asthma diary

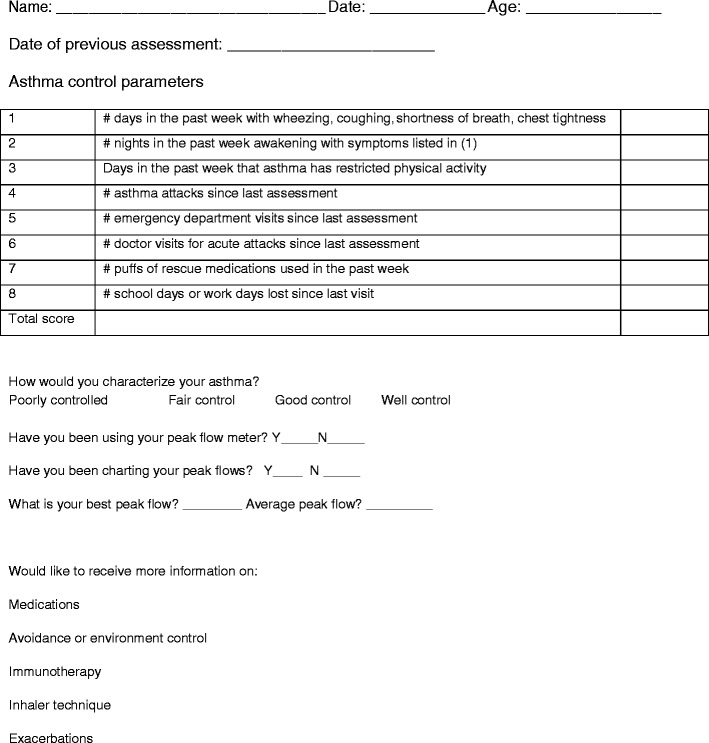

In addition to home monitoring, patients should complete an asthma assessment questionnaire each time they visit their asthma care provider (Fig. 8). From the asthma assessment questionnaire, a great deal of important information can be obtained, such as whether the patient is compliant with medications, if they are overusing their rescue inhaler, are they having too many nighttime awakenings, is their daily activity restricted, and so on, all of which speaks to asthma control.

Fig. 8.

A sample asthma assessment tool

Asthma Action Plans

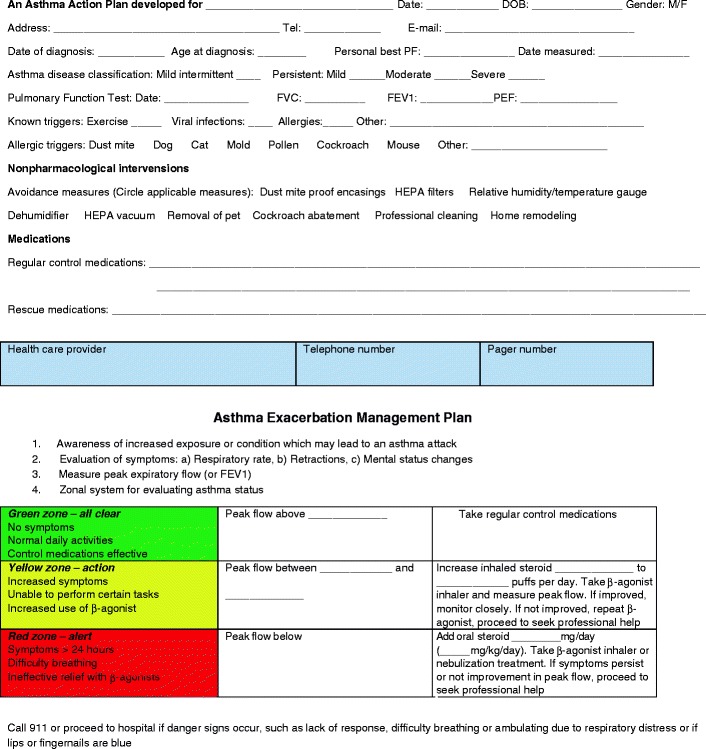

The components of an asthma management plan are shown in Fig. 9. Asthma action plans are an important part of successful asthma management. They provide written guidance for parents and patients once they leave the doctor’s office or hospital. This is important because sometimes asthma treatment can be complicated for patients, and parents and patients can become overwhelmed with all the instructions about multiple medications, how to use a peak flow meter, and what to do in an emergency. The asthma action plan can also serve as a refresher course for patients, who have recently been discharged from the hospital after an admission for an asthma exacerbation [44]. Involving schoolteachers in a child’s asthma action plan can also help to improve the overall asthma control and quality of life [45].

Fig. 9.

An asthma management plan. An asthma action plan must include information on how to assess the child’s condition. Known triggers should be listed and the PEF zonal system can be used to provide easy instructions for patients and parents. The form also allows for entering medication doses

One of the reasons for the persistently high asthma morbidity in the face of newly developed asthma medications is that patients do not usually follow all the instructions to ensure effective asthma control. Written action plans help circumvent this problem, making it easier for patients to be compliant. Besides medication instructions, asthma action plans can also give instructions on environmental control and avoidance of triggers. Instructions on when to seek professional help is also entered on an asthma action plan.

Objective Methods of Assessing Airway Inflammation

Nitric Oxide

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) is elevated in children with asthma [46]. It has been demonstrated to be a marker of eosinophilic airway inflammation in children with asthma, and it also responds to glucocorticoid therapy [47–49]. Measurement of FeNO may be an effective way of monitoring airway inflammation and bronchial hyperresponsiveness [50]. Recently, increased levels of FENO have been found to correlate with risk of asthma in children [51]. Equipment to measure FeNO is currently available [52], but this test has not yet been widely adopted, mainly because there is still controversy regarding its value in managing the asthmatic child [53–55] but also because insurance companies have been slow to reimburse for this test adequately. As these issues are sorted out, FeNO may yet prove to be a valuable tool to assess airway inflammation.

Eosinophil Cationic Protein

Elevated eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) levels in cord blood are predictive of atopy. ECP is a marker of eosinophil activation. Serum ECP levels correlate with airway inflammation in wheezing children [56]. In a retrospective study of 441 patients with respiratory disease, the sensitivity and specificity for asthma were 70% and 74%, respectively. ECP was not predictive for any other respiratory disease [57]. When patients with asthma are bronchial challenged with allergen, activation of eosinophils and generation of specific eosinophilic mediators result. Evaluation and continued monitoring of eosinophil and ECP may be a way to assess efficacy of asthma therapy and airway inflammation in children with allergic asthma [58]. Both leukotriene receptor antagonists and inhaled corticosteroids have been associated with a reduction in sputum ECP levels in patients with mild to moderate persistent asthma [59, 60]. A response of serum ECP levels to glucocorticoid treatment has also been observed [61].

Pharmacologic Management

Controller Medications

Inhaled Corticosteroids

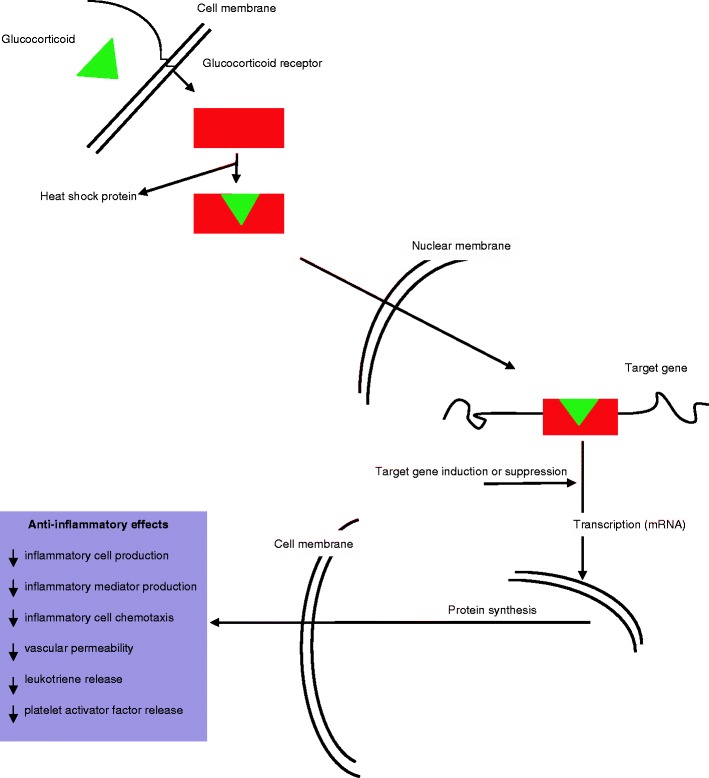

The beneficial effect of ACTH in the treatment of asthma was shown in 1949 [62, 63]. Subsequently, oral corticosteroids were also shown to be beneficial but side effects limited their widespread use. The introduction of inhaled corticosteroids in 1972 heralded a new age in asthma treatment, and inhaled corticosteroids have been the first-line treatment in the control of asthma since then. Corticosteroids work by switching off inflammatory genes through their interaction with the glucocorticoid receptor and recruitment of histone deactylase-2. By regulation of transcription of inflammatory genes or their promoters, they exert a number of anti-inflammatory effects (as illustrated in Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Mechanism of action of glucocorticoids

All of the different inhaled corticosteroids can be used in children. Budesonide is also available in nebulized form, in three strengths, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mg. A multicenter study of 481 children demonstrated improvement in daytime and nighttime symptoms when treated with nebulized budesonide. Inhaled corticosteroids are now the first-line drug for treatment of mild, moderate, and severe persistent asthma [64] (Table 10).

Table 10.

Steroid dose equivalency

| Scientific name | Dose equivalency (mg) | Relative potency | Half-life (h) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortisone | 25 | 0.8 | 8–12 | |

| Hydrocortisone | 20 | 1 | 8–12 | |

| Prednisone | 5 | 4 | 12–36 | Available in liquid or tablet form |

| Prednisolone | 5 | 4 | 12–36 | Available in liquid or tablet form |

| Methylprednisolone | 4 | 5 | 12–36 | Used in ED or hospitalized patients |

| Triamcinolone | 4 | 5 | 12–36 | |

| Paramethasone | 2 | 10 | 36–72 | |

| Dexamethasone | 0.75 | 26.67 | 36–72 | |

| Betamethasone | 0.6 | 33.34 | 36–72 |

The issue of adverse effects of inhaled steroids in children has been extensively studied. Steroids are associated with numerous side effects (see Table 11). Most of these have been attributed to oral or parenteral steroids. In children with asthma, the major concerns regarding inhaled or nebulized steroids have been the effect on growth [65–67]. Studies to determine if inhaled corticosteroids indeed have such an effect are difficult to conduct because asthma itself has been associated with growth retardation [68]. Results have therefore been inconsistent; however, the bulk of the evidence suggests that even if there is growth retardation, this is usually reversible and there is a period of “catch-up” growth. Moreover, even if corticosteroids do indeed affect growth, the extent of growth retardation is minimal. Thus, the risk of growth retardation is small compared to the potential for serious asthma exacerbations. Adrenal suppression in children on inhaled steroids is also not a significant problem. In a study of 14 children on a dry powder beclomethasone dipropionate inhaler, there was no suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis [69]. The dose of beclomethasone was 12–25 μg/kg/day. Other studies have failed to demonstrate adverse effects on the HPA axis [70, 71]. On the other hand, use of high doses of fluticasone has been shown to cause HPA axis suppression [72]. It is not known if there is any clinical significance to these observed effects. A list of the available inhaled corticosteroids and their daily dosing regimens in pediatrics is shown in Table 12.

Table 11.

Adverse effects of asthma medications

| β-Agonists | Inhaled steroids | Systemic steroids | Anticholinergics | Leukotriene pathway modifiers | Theophylline | Anti-IgE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tremors | Dysphonia | Hyperglycemia | Dry mouth | Elevated liver enzymes | Gastritis | Anaphylaxis |

| Tachycardia | Oral thrush | Hypertension | Blurry vision | Churg–Strauss syndrome | Seizures | |

| Muscle spasmsa | Growth retardationa | Osteonecrosis | Increased wheezing | Risk of suicide | Tremorsa | |

| Hypokalemia | Adrenal suppressiona | Osteoporosis | Insomnia | |||

| Tachyphylaxis | Cushing’s syndrome | Nausea/vomiting | ||||

| Hyperglycemia | Adrenal suppressiona | Tachycardia | ||||

| Headache | Moon faciesa | Hypokalemia | ||||

| Hyperactivitya | Gastritisa | Hypoglycemia | ||||

| Increase in asthma mortalityb | Psychological disturbancesa | Central nervous system stimulation | ||||

| Acnea | Headache | |||||

| Cataracts | Hyperactivitya | |||||

| Hirsutisma | ||||||

| Decreased platelet function | ||||||

| Growth retardationa |

aOf particular importance in children

bNot clearly established, may be related to other confounding issues

Table 12.

Daily pediatric doses of inhaled corticosteroidsb

| Medication | Pediatric indication | Dose/actuation (μg) | Dosing frequency | Mild persistent | Moderate persistent | Severe persistent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of actuations/day | Number of actuations/day | Number of actuations/day | ||||

| Beclomethasone dipropionate | 5–11 years | 40 | Bid | 2 | 2–4 | |

| 80 | Bid | 2 | 2 | |||

| Triamcinolonea | 6–12 years | 100 | bid to qid | 4–8 | 8–12 | 8–12 |

| Flunisolide | 6–15 years | 250 | Bid | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Budesonide | 6 years and older | 200 | Bid | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Nebulized budesonide | 12 months to 8 years | Ampules of 250, 500 and 1,000 mg | Bid | 1 mg total daily dose | ||

| Fluticasone | 12 years and older | 44 | Bid | 2–4 | 4–10 | |

| 110 | 2–4 | 4–8 | ||||

| 220 | 2–4 | 4–8 | ||||

| Fluticasone diskus | 4–11 years | 50 | Bid | 2–4 | ||

| 100 | 1–4 | 2–4 | ||||

| 250 | 1–4 | 2–4 | ||||

| Mometasone furoate | 4–11 years | 110 | Bid | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 220 | Bid | 1 | 2 | |||

aTriamcinolone inhaler is no longer commercially available

bThese are suggested doses modified from the package inserts of each drug

Long-Acting β-Agonists

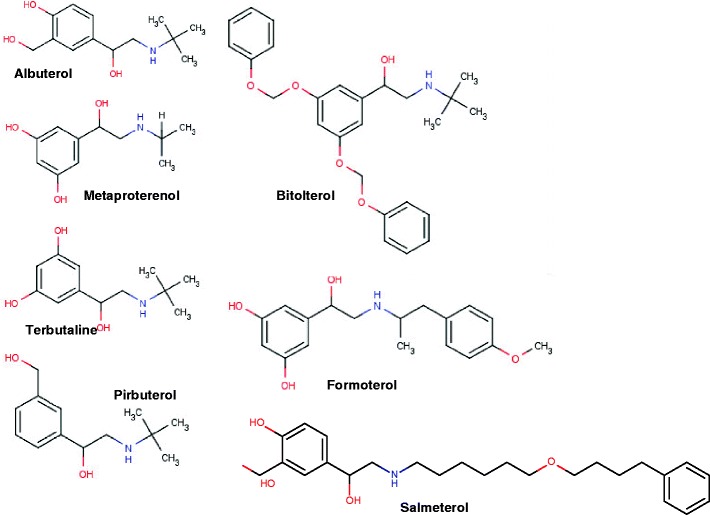

Long-acting β-agonists (LABAs) are available either alone or in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid. The two available long-acting β-agonists currently available are salmeterol xinafoate and formoterol fumarate. Salmeterol xinafoate possesses a long hydrocarbon chain connecting the binding site with the active site of the molecule. Theoretically, this conformation allows repetitive interaction between the active site and the target receptor, as the binding site is firmly attached to an alternate site on the cell membrane and the long chain acts as a tether. Salmeterol is indicated down to age 4. It used to be available as an MDI and the diskus, but now only the diskus is available. The dose per puff in the diskus is 50 μg and should be taken twice daily. The terminal elimination half-life of salmeterol is 5.5 h. Formoterol is available in an aerolizer, a dry powder device in which a capsule must be punctured in a specialized chamber. A total of 12 μg of drug is contained in one capsule. Formoterol is also dosed twice daily. The mean elimination half-life of formoterol in healthy subjects is 10 h. The structures of salmeterol and formoterol are illustrated in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Structure of the β-adrenergic agonists. Comparison of the structures of albuterol and salmeterol helps to explain the long half-life of salmeterol. The long chain connects the binding site to the active site of the molecule. Once bound at the binding site, the long chain is theorized to swing back and forth, allowing the active site to repeatedly come in contact with the receptor site, prolonging the action of the drug

The LABAs are not generally considered first-line treatment for persistent asthma, and the current recommendation is that it be used as add-on therapy. Recently, case reports appeared in the literature of asthma related deaths associated with salmeterol use. The FDA subsequently attached a black box warning on increased asthma related deaths to the LABA class of drugs. The issue is, however, still under significant debate, due to the presence of other confounding variables that may or may not have been taken into account in the studies. The recommendation for the use of LABAs has now changed, whereby once the patient is stabilized on combination therapy, he or she should be weaned off the LABA. It remains to be seen if there will be adverse consequences of such a recommendation [73].

Cromolyn and Nedocromil

These two unrelated compounds have an excellent safety profile. Their chemical structures are illustrated in Fig. 12. Both are mast cell stabilizers, and both also inhibit the activation and release of inflammatory mediators from eosinophils. This appears to be mediated through blockage of chloride channels [74]. Both early- and late-phase reactions to allergen challenge are inhibited. Cromolyn is derived from the plant, Ammi visnaga, or bishop’s weed. The commercial product can be administered in either nebulized form or by MDI. The dose of cromolyn via MDI is 1 mg per actuation, where as the dose of nedocromil is 2 mg per actuation delivered from the valve and 1.75 mg per actuation delivered from the mouth piece of the inhaler. The dose of cromolyn delivered via nebulizer is 20 mg per treatment. The terminal elimination half-life of nedocromil sodium is 3.3 h. Nedocromil sodium is indicated in children 6 years of age or older. Cromolyn sodium is regularly used in very young children via nebulizer.

Fig. 12.

Structure and anti-inflammatory effects of cromolyn and nedocromil

Because of the unfavorable dosing schedule, cromolyn, a previously widely used medication, has given way to other nebulized anti-inflammatory medications, such as the glucocorticoids. Nedocromil has an unpleasant taste and, along with cromolyn, has fallen out of favor recently.

Leukotriene Pathway Drugs

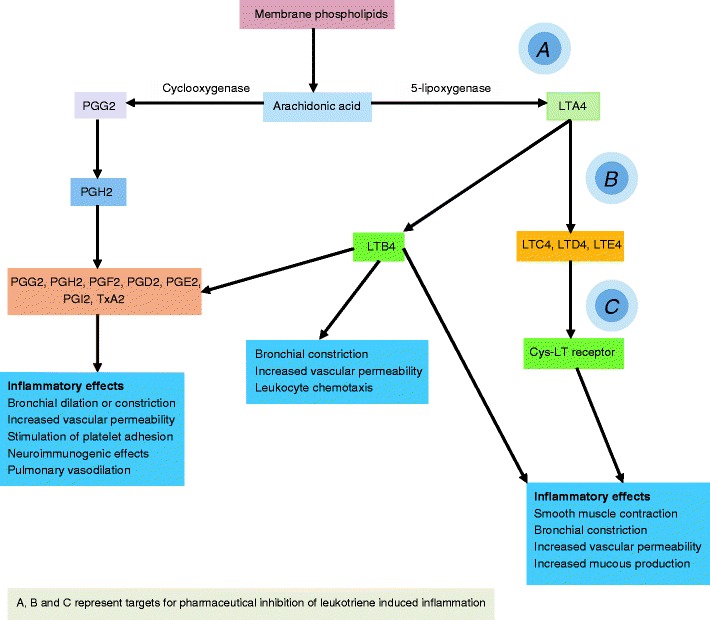

Drugs that block the effects of leukotrienes were first introduced in the early 1990s. Two strategies were used in the development of these drugs, inhibiting their synthesis or blocking their action at the Cys-LT receptor level. Drugs that block leukotriene synthesis, such as zileuton, have been associated with liver toxicity. The leukotriene receptor antagonists have a much better safety profile and dosing schedule and have been the more widely used medications. The mechanism of action of leukotrienes is shown in Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Mechanism of action of leukotriene pathway modifiers

As an inflammatory mediator in asthma, leukotrienes are 1000 times more potent than histamine [75]. The effects of LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4 on the Cys-LT receptor include an increase in mucous production, constriction of bronchial smooth muscle, augmentation of neutrophil and eosinophil migration, and stimulation of monocytes aggregation. In general, side effects of the leukotriene receptor antagonists are mild, with the exception of Churg–Strauss syndrome [76], a vasculitis associated with peripheral eosinophilia, elevated serum total IgE, patchy pulmonary infiltrates, cutaneous purpuric lesions, and pleural effusions. Leukotriene pathway modifiers can also affect metabolism of theophylline and a number of other drugs.

Montelukast, the most commonly used leukotriene pathway drug, is approved in children 1 year and older for asthma, 6 months and older for perennial allergic rhinitis, and 24 months and older for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Montelukast has been particularly useful in the treatment of cough variant asthma in children [77]. Early reports of an association between suicide and montelukast have been re-assessed, and the conclusion is that the risk of suicidal ideation in montelukast use is low. However, it was recommended that patients should be screened for behavioral anomalies including suicide ideation, which are generally more common in adolescents and the elderly [78].

Antihistamines

Whether to use antihistamines in children with asthma has been a hotly debated topic. The FDA originally had a warning on using antihistamines in asthma which was a class effect, so any newer antihistamines that were introduced all carried the same warning. However, while the first generation antihistamines had side effects that could potentiate an asthma exacerbation, such as the anticholinergic effects of drying, as well as the sedative effects, the second-generation antihistamines have much less of these adverse effects and should be safe in asthmatics. They should also provide some benefit, especially in children, where the greater proportion of asthma is associated with allergies [79]. The currently available second-generation antihistamines in the USA are cetirizine, levocetirizine, loratadine, desloratadine, and fexofenadine. These drugs block the allergic effect of environmental allergens, but cetirizine also inhibits leukocyte recruitment and activation and eosinophil migration [80] and has been shown to decreases late leukocyte migration into antigen-challenge skin blister fluid chambers [81]. All three inflammatory cell lines, including neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils, were affected.

Theophylline in Childhood Asthma

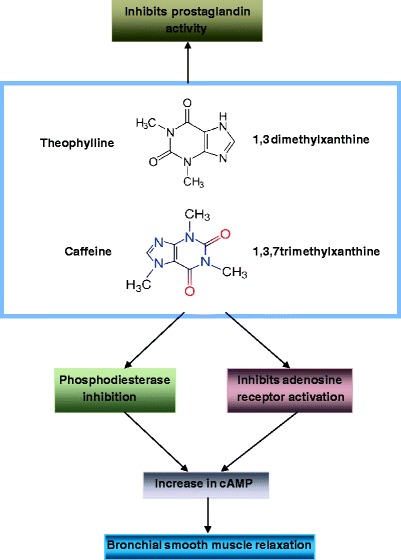

Theophylline and aminophylline had their heyday in the 1980s, when almost every child with an asthma exacerbation requiring hospital admission was started on an aminophylline drip. Similarly, most patients with asthma were placed on theophylline as a maintenance therapy. The use of this class of medications has decreased significantly since then, due to its narrow therapeutic window, and potentially severe side effects (Table 11). Aminophylline is metabolized to theophylline, which is then metabolized to caffeine.

Theophylline acts as a phosphodiesterase inhibitor (Fig. 14). Its efficacy in improving symptom scores and pulmonary function test parameters are similar to inhaled steroids. Therefore, despite the undesirable effects of theophylline, there may still be role for its use as a steroid sparing agent in children with severe persistent asthma, especially those on systemic steroids. Theophylline levels should be monitored regularly every 2 to 3 months or more frequently if there are dosage changes, signs of adverse effects, or lack of efficacy. A list of factors and agents that influence theophylline levels and their effect is shown in Table 13.

Fig. 14.

Structure and bronchodilatory effects of theophylline and known actions of theophylline and caffeine. Actual mechanism for the bronchodilatory effect of methylxanthines is not completely understood. Phosphodiesterase inhibition appears to be the most likely mechanism, but theophylline is known to have other activity, as shown

Table 13.

Factors affecting theophylline metabolism

| Factor or drug | Effect on theophylline levels |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | |

| Ketolides | Increase |

| Ciprofloxacin | Increase |

| Rifampin | Decrease |

| Macrolides: erythromycin, clarithromycin | Increase |

| Antiepileptics | |

| Phenobarbital | Decrease |

| Carbamazepine | Decrease |

| Phenytoin | Decrease |

| Other drugs | |

| Aminoglutethimide | Decrease |

| Disulfiram | Increase |

| Ticlopidine | Increase |

| Propranolol | Increase |

| Cimetidine | Increase |

| Allopurinol | Increase |

| Calcium channel blockers | Increase |

| Methotrexate | Increase |

| Other factors | |

| Diet | Increase/decrease |

| Obesity | Increase |

| Hypoxia | Increase |

| Smoking | Decrease |

| Viral illness | Usually increase |

| Pediatric and geriatric population | Usually increase |

Monoclonal Anti-IgE

Omalizumab (Xolair) is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized IgG1a monoclonal antibody, which binds specifically to human IgE. Binding of IgE by omalizumab inhibits both early- and late-phase reactions of asthma. Effects of omalizumab include a reduction in serum IgE levels and a decrease in allergen-induced bronchoconstriction [82]. Omalizumab is indicated for patients 12 years of age or older who have moderate to severe persistent allergic asthma with a positive skin or blood allergy test, who have IgE levels between 30 and 700 IU/ml. Table 14 shows the dosing schedule for omalizumab. Side effects include malignancies, anaphylactic reactions, and local injection reactions. The high cost of Xolair can be potentially offset by savings in the cost of asthma exacerbations, e.g., hospital costs, outpatient emergency department visits, rescue medications, and indirect costs from loss of productivity by the patient [83].

Table 14.

Dosing schedule for omalizumab

| Pretreatment serum IgE (IU/ml) | Body weight (kg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–60 | >60–70 | >70–90 | >90–150 | |

| Every 4-week dosing | ||||

| ≥30–100 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| >100–200 | 300 | 300 | 300 | See below |

| >200–300 | 300 | See below | See below | |

| >300–400 | See below | |||

| >400–500 | ||||

| >500–600 | ||||

| Every 2-week dosing | ||||

| ≥30–100 | See above | See above | See above | See above |

| >100–200 | 225 | |||

| >200–300 | 225 | 225 | 300 | |

| >300–400 | 300 | 300 | 375 | Do not dose |

| >400–500 | 300 | 375 | Do not dose | |

| >500–600 | 375 | Do not dose | ||

Adapted from omalizumab package insert. Omalizumab is FDA approved in children over 12 years of age

Reliever Medications (Rescue Medications)

Short-Acting β-Agonists

The mechanism of action of the β-agonists is through activation of the β2-adrenergic receptors on airway smooth muscle cells, which leads to activation of adenyl cyclase. This, in turn, leads to an increase in the intracellular concentration of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). cAMP activates protein kinase A, causing inhibition of phosphorylation of myosin and lowering of intracellular calcium concentrations, which then results in relaxation of bronchial smooth muscle. β2-Adrenergic receptors are present in all airways, from the trachea to the terminal bronchioles. Another effect of the increase in cAMP concentration is the inhibition of mediator release from mast cells. Adverse effects of β-agonists include paradoxical bronchospasm, cardiovascular effects, central nervous system stimulation, fever, tremors, nausea, vomiting, and an unpleasant taste (Table 11).

The short-acting β-agonist (SABA) used include albuterol, levalbuterol, pirbuterol, bronkosol, isoproterenol, metaproterenol, and terbutaline (Fig. 11). The more recently developed β-agonists are more specific to β2-adrenergic receptors, optimizing the effects on bronchial smooth muscle while reducing cardiac side effects, and have made older less-specific drugs such as metaproterenol and isoproterenol obsolete. Dosing recommendations for short-acting β-agonist inhalers are shown in Table 15. Albuterol, the most common used β-agonist, is available as a 0.083% nebulization solution. The use of β-blockers is a relative contraindication in children with asthma. β-Blockers have been associated with worsening asthma [84].

Table 15.

Characteristics of inhaled or nebulized bronchodilator preparations

| Generic name | Dosage/inhalations or puff | Available delivery devices | Dosing frequency | Max puffs/d | Half-life (h) | Onset of action (min) | Time to peak effect (min) | Duration of action (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albuterol | 90 μg/puff or 2.5 mg per nebulization | MDI, D, C, N | 2 puffs q4h prn, 1 tmt q4h prn | 12 | 1.5 | 6 | 55–60 | 3 |

| Levalbuterol | 0.31, 0.63, or 1.25 mg per nebulization or 90 μg/MDI puff | MDI, N | 2 puffs q4h prn, 1 tmt q4h prn | 12 | 3.3 | 10–17 | 90 | 8 |

| Metaproterenol | 630 μg/puff or 15 mg nebulization | MDI, N | 2 puffs q4h prn or 1 tmt q4h prn | 12 | N/A | 5–30 | 60–75 | 1–2.5 |

| Pirbuterol | 200 μg | A | 2 puffs q4–6 h prn | 12 | N/A | 5 | 50 | 5 |

| Bitolterol | 370 μg | MDI, N | 2 puffs q6h prn | 12 | N/A | 3–4 | 30–60 | 5–8 |

| Formoterol | 12 μg | D | 2 puff q12h | 2 | 10 | 5 | 60 | 12 |

| Salmeterol | 25 μg | MDI, D | 2 puffs q12h | 4 | 5.5 | 10–20 | 45 | 12a |

| Ipratropium | 18 μg/puff or 500 μg per nebulization | MDI, C, N | 2 puffs q6h prn or 1 tmt q6h | 12 | 2 | 15 | 60–120 | 3–4 |

Some of these are no longer commercially available

MDI metered dose inhaler (only HFA available now), A autoinhaler, D dry powder inhaler, C combination inhaler, N solution for small volume nebulizer

aLate phase reaction may be inhibited up to 30 h

Albuterol is a 50–50 racemic mixture of the stereoisomers R-albuterol (levalbuterol) and S-albuterol. Levalbuterol is available in both inhaler and nebulizer solution form. There are three available doses of levalbuterol, 0.31, 0.63, and 1.25 mg for nebulization. Levalbuterol increases mean FEV1 by 31–37% in children between the ages of 6 and 11 [85]. The elimination half-life of levalbuterol is 3.3 h compared to 1.5 h for albuterol.

Albuterol is also available in oral form, either as a 2-mg/5-ml syrup or a sustained release 4-mg tablet. The oral dose in children is 0.03–0.06 mg/kg/day in three divided doses (no more than 8 mg per day). Terbutaline is also available orally in 2.5 and 5 mg tablets and is indicated for use in children over 12 years of age.

Anticholinergics

Anticholinergic inhalers are indicated for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease but may be of some value in the treatment of the asthmatic during an exacerbation. The mechanism of action of ipratropium bromide is through competitive inhibition of M2 and M3 muscarinic cholinergic receptors. This leads to a decrease in airway vagal tone and decreased mucous gland secretion. Bronchoconstriction is also inhibited by anticholinergic agents [86]. Ipratropium bromide is available in nebulized form (2.5 ml of a 0.02% solution = 500 μg), or by HFA MDI (17 μg/dose from the mouthpiece). Ipratropium bromide is not well absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract. The elimination half-life of ipratropium bromide is 1 h when taken by MDI or administered intravenously.

Mucolytics

The use of mucolytics, such as N-acetylcysteine and S-carboxymethycysteine, in childhood asthma is controversial. Mucolytics exert their action by breaking up the disulfide bonds between mucin chains and allowing for easier clearance of mucous. On the other hand, they can cause bronchoconstriction. Although animal studies have demonstrated that N-acetylcysteine can improve gas exchange after methacholine challenge [87], there is currently no clinical indication for the use of mucolytics in the treatment of childhood asthma.

Oral or Parenteral Steroids

Fortunately, the use of systemic steroids in the treatment of asthma has decreased in countries where access to preventative, controller medications is easy and unrestricted. Systemic steroids, administered orally or parenterally on a chronic basis, are associated with a long list of adverse effects, many of which are potentially more serious than the disease they are being used to treat. These side effects are listed in Table 11. One important side effect that is sometimes forgotten is osteonecrosis. While corticosteroid-induced osteonecrosis is more common in autoimmune diseases and transplant patients than in asthma, one should still have a high index of suspicion when treating an asthmatic child who has been on steroids for a long time [88]. Generally speaking, a short course of steroids to treat an asthma exacerbation is acceptable from a risk benefit standpoint. In this case, if the corticosteroid course is less than 7 days, no tapering of dose is needed. A tapering schedule should be formulated for those patients in whom steroids are being used for longer than 1 week. If the patient requires multiple courses of steroids, then the possibility of developing serious side effects should be considered.

There are several corticosteroids available to treat asthma exacerbations. These are shown in Table 10. Many of the oral preparations have a very bad taste and may need to be disguised in foods in order to be able to administer them to young children. There is also available at least one form in an oral disintegrating tablet, which will facilitate compliance in young children.

Treatment of Exercise-Induced Asthma

Exercise is a common trigger for asthma and is particularly relevant in children, as many children are active in sports. Short-acting β-agonists are widely used, whereby the child takes two puffs of an albuterol inhaler prior to exercising. This has the effect of shifting the stimulus response curve to the right. Inhaled albuterol or terbutaline provide relief for up to 1 h during exercise [89]. Other short-acting bronchodilators that have been used in EIA include fenoterol [90] and bitolterol [91]. Oral bronchodilators have provided longer relief, up to 6 h for albuterol [92] and 2–5 h for terbutaline [93]. Cromolyn and nedocromil have been found to protect against EIA for 120 and 300 min, respectively [94, 95]. Theophylline has also been used in EIA, but the narrow therapeutic window and the lack of benefit observed at lower doses has hindered its widespread use [96]. The use of ipratropium bromide in EIA has not produced consistent results [97]. Controller medications that have played a role in preventing EIA include inhaled corticosteroids and the long-acting bronchodilators salmeterol [98] and formoterol. Leukotriene receptor antagonists have also been shown to be of some value in preventing EIA in children [99]. The data on ketotifen [100], calcium channel blockers [101–103], and antihistamines [104] in the treatment of EIA are conflicting.

Inhalation Devices in Children

Metered dose inhalers were first introduced in 1955 to deliver a predetermined amount of drug to the airways. The devices have undergone significant evolution since then and now are the most common device to carry drugs to treat asthma. Dry powder inhalers (DPI) are an alternative to metered dose inhalers. While the ability to deliver drug straight to the airways has revolutionized asthma treatment, the use of these devices in children presents some special considerations. The most important of these is the ability of young children to use these devices effectively. Specifically, this is the ability of the child to (1) understand how to use them and (2) be coordinated enough to use them accurately and effectively. Metered dose inhalers require considerable more coordination than DPIs, although spacer devices do help. If a child is found to be unable to effectively use one of these devices, then it would be much more beneficial to the asthmatic child to continue with the use of nebulizers. A comparison of the various drug delivery devices is shown in Table 16. The table also shows the most common age at which these inhalers can typically be used, although it is important to appreciate that there is a significant variability to these ages.

Table 16.

Comparison of inhaler devices

| CFC inhalers | HFA inhalers | Autoinhalers | Dry powder inhalers | Spacer devices | Nebulizers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | No longer available | Widespread | Rare | Increasing | Common | Widespread |

| Portability | Easy | Easy | Easy | Easy | Some are cumbersome | Smaller devices are available |

| Ease of use | Difficult | Difficult | No need for coordination | Need for adequate breath actuation | Improves effectiveness of MDI | No coordination necessary |

| Age range of use | 5 years and older | 5 years and older | 4 years and older | 4 years and older | May allow for use of MDI at an earlier age | Any age |

| Available for | Not available | SABA, LABA, Corticosteroids, Ipratropium bromide | SABA (pirbuterol) | LABA, Corticosteroids, Combination products | N/A | SABA, cromolyn, nedocromil, ipratropium bromide, corticosteroids |

| Cost/value | N/A | Expensive/good | Expensive/fair | Expensive/good | Moderate/good | Expensive/good |

| Comments | CFCs no longer available | The standard for MDI devices | Difficult to find | Dose lost if child exhales through device | Improves drug delivery to airways | Most reliable way to deliver drug—less dependent on patient technique |

Immunotherapy in Childhood Asthma

Also referred to as hyposensitization, desensitization, or allergy shots, immunotherapy plays a significant role in the treatment of pediatric asthma. Studies done in children who were allergic to dust mite [105], cat [106], dog [106–110], mold [111], grass [112–114], ragweed [115, 116], olive tree [117], and other allergens have demonstrated a beneficial effect of subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT). A study of 215 patients with dust mite allergy demonstrated that those patients with an FEV1 greater than 90% were four times as likely to benefit from immunotherapy to house dust mite, compared with patients with FEV1 less than 60%. Moreover, patients under the age of 20 years were three times more likely to improve than those more than 51 years of age [118]. Indications for immunotherapy include clear evidence of symptom–exposure relationship, perennial symptoms, and inadequate control with medications. Recent advances in sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) may provide another option for hyposensitization in children with allergic asthma.

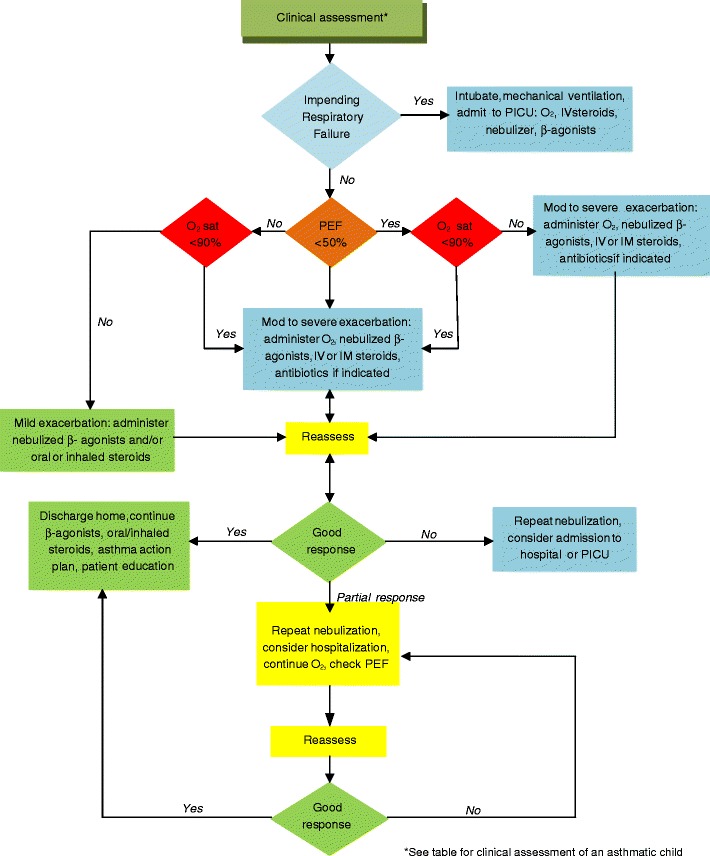

Emergency Treatment of Status Asthmaticus

A child may present to an emergency room or urgent care setting in respiratory distress but without a diagnosis of asthma. It is important for the emergency room physician or provider to be able to quickly formulate a differential diagnosis in order to administer the correct treatment. Assessment of respiratory distress involves the evaluation of patient symptoms and signs including heart rate, respiratory rate, retractions, mental status changes, presence of cough or wheezing, pulsus paradoxicus, and, if quickly available, peak flow measurement and pulse oximetry. A differential diagnosis of asthma is shown in Table 4. If wheezing is present, other causes must be ruled out, including foreign body aspiration or bronchiolitis. A chest radiograph may help in this case and also in identifying potential comorbidities of asthma, such as atelectasis or pneumothorax.

A comprehensive initial evaluation of the patient in respiratory distress can be done fairly quickly, and if the respiratory distress is severe, then treatment must be initiated promptly. In an asthmatic in status asthmaticus, a short-acting β-agonist such as albuterol or levalbuterol should be administered quickly, preferably via a small volume nebulizer. If there is time, measurement of peak flow or spirometry done prior to and after the treatment can help to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment, but one should not delay treatment if the child’s condition is serious. If the child appears dyspneic, the patient should be placed on a cardiac monitor that can provide a rhythm and oxygen saturation. Intravenous (IV) access should be established in patients who are in respiratory distress, or to maintain hydration status. Parenteral steroids may be initiated for moderate to severe asthma exacerbations. Methylprednisolone 1 to 2 mg/kg can be given intravenously or intramuscularly. This can be continued every 6 h if the child requires admission. If the child’s condition improves quickly and he or she remains stable, the child may be discharged home on a short course of oral steroids (prednisone 1 to 2 mg/kg/day) with close follow-up and an action plan with detailed instructions. Measurement of peak flow and oxygen saturation should be done prior to discharge.

Epinephrine, although always important to consider, is less commonly used because of the abundance of other medications with lesser side effects. Side effects of epinephrine include tremors, hypertension, tachycardia, neutrophil demargination, and cardiac stimulation. In very severe cases, subcutaneous epinephrine (1:1,000) has been used in the treatment of the asthmatic child. The dose is 0.01 ml/kg to a maximum of 0.3 ml. The dose can be repeated if the response is inadequate. Having an epinephrine autoinjector available obviates the need to measure out the dose and saves time.

Dehydration can be a factor in the successful treatment of the asthmatic child because it results in drying up of bronchial mucous and/or electrolyte imbalances, making the treatment of the asthmatic more difficult. Concomitant infection, such as pneumonia or sinusitis, should be treated with antibiotics. Other medications used in the treatment of the acute asthmatic include nebulized corticosteroids, nebulized cromolyn, leukotriene receptor antagonists, theophylline or aminophylline, and nebulized anticholinergic agents. The doses of emergency medications and the size of emergency equipment that is used in the pediatric population are summarized in Table 17.

Table 17.

Emergency equipment and medication doses in children

| Emergency medications | |||||