Abstract

Single chain variable fragments (scFvs) are generated by joining together the variable heavy and light chain of a monoclonal antibody (mAb) via a peptide linker. They offer some advantages over the parental mAb such as low molecular weight, heterologous production, multimeric form, and multivalency. The scFvs were produced against more than 50 antigens till date using 10 different plant species as the expression system. There were considerable improvements in the expression and purification strategies of scFv in the last 24 years. With the growing demand of scFv in therapeutic and diagnostic fields, its biosynthesis needs to be increased. The easiness in development, maintenance, and multiplication of transgenic plants make them an attractive expression platform for scFv production. The review intends to provide comprehensive information about the use of plant expression system to produce scFv. The developments, advantages, pitfalls, and possible prospects of improvement for the exploitation of plants in the industrial level are discussed.

Keywords: Recombinant protein, Targeted expression, Glycoengineering, scFv

Introduction

Antibodies are used extensively as medicines, diagnostic molecules, environment clean-up agents, biosensors, and as a bait in the purification process in various commercial industries [1–3]. Due to the large size, complex nature, and extensive post-translational modifications, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with therapeutic applications are produced mostly using the mammalian expression systems. The cost factor involved in maintaining the manufacturing unit according to the GMP (Good Manufacturing Practise) regulations makes the commercial production of mAb an exorbitant process. A single chain variable fragment (scFv) is the smallest fragment of an antibody with the same antigen-binding specificity [4, 5]. Multimeric scFv comprising of more than one pair of heavy and light chains can be generated by changing the length of peptide linker. Multimerization can also be made by using specific peptides which have the natural ability to induce it [6, 7]. Multivalent scFv showing affinity to more than one protein at the same time can be generated through genetic engineering [8–11]. The multivalent scFv binds to multiple antigens at the same time and can improve the diagnostic accuracy in any antibody-dependent procedure.

The concept and practice of using plants as recombinant protein expression platforms have made significant progress in the last two decades. There are many antibodies expressed successfully in plants [12–15]. The differences in the post-translational modifications between mammalian cells and the plant cells were a serious concern in using plants for the recombinant antibody expression. Genetic manipulations leading to the mammalian-like post-translational modifications in the model plant systems resulted in the biosynthesis of antibodies equivalent to mammalian products [16–18]. Even though biologically active mAbs can be expressed successfully in plants, a more feasible approach would be the expression of antibody fragments. The model plants like Nicotiana and Arabidopsis are studied thoroughly to identify the most appropriate promoter, suitable integration site in the host genome, influence of signal/tag in expression, viability of subcellular targeting/secretion of the recombinant protein, organ-specific expression, expression as transient or stable protein, and the extraction and purification strategies for different target proteins. This review presents a comprehensive report on the scFv’s and scFv-Fc’s expressed so far in plant systems.

Immunoglobulin (Ig) and Single Chain Variable Fragment (scFv)

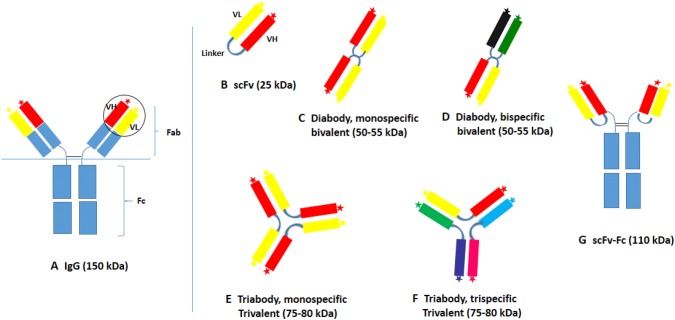

The conventional antibody consists of two heavy chains and two light chains connected with disulfide bonds. The antibody structure can be divided into a constant Fc domain (crystallizable fragment domain) and the Fab fragment (antibody binding fragment) contains the Fv domains (variable fragment domains) at the end of both the arms (Fig. 1a). In humans, the antibody synthesized is usually glycosylated in the Fc region, which stabilizes the antibody and is necessary for the antibody-dependent immune responses. Enzymatic cleavage of antibody at the N-terminal side of the inter-heavy chain disulfide bridges results in the formation of Fc and Fab fragments [19, 20]. There are two variable regions in a Fab fragment interact with the antigen and each of these units represent the smallest functional antigen-binding domain.

Fig. 1.

scFv antibody formats expressed in plants. Immunoglobulin antibody (a) showing the variable regions (heavy and light chains in circle). scFv (b) represent the variable heavy and light chains connected together with a peptide linker. ScFv can be engineered to generate multivalent, multi-domain structures. dimeric monospecific (c) and bispecific (d) forms of scFv and multimeric scFv (e), molecule generated by the shortening of linker peptide. Multivalent (f) scFv with the paratope specificity for more than one antigens, generated by arranging the VH and VL of different antibodies in a specific order. In scFv-Fc (g), the scFv is bound to the Fc region of the antibody

The scFv can be generated by amplifying the variable regions of the Fab fragment from the mAb and by linking it together with a flexible peptide linker (usually (GGGGS)3) [4, 5, 21] (Fig. 1b). Advances in molecular techniques further improved the prospect of engineering scFv to improve its specificity, avidity, affinity, and half-life. Multimerization of the variable domains using, the linker [22], the tetramerization domain of a native protein like p53 [7], the leucine zippers [23], or the C-terminal fragment of C4-binding protein [6] improved the affinity of the scFv to a great extent. The immunogenicity generated by the Fc portion of the antibody is absent in the conventional scFv molecule. The scFv expressing together with the Fc region of IgG (scFv-Fc) is found to be beneficiary with its “effector” functions in many reports [24, 25] (Fig. 1g). Antibody fragments of therapeutic and diagnostic importance have been expressed in mammalian systems [26, 27] plants [28–30] and in prokaryotes [29, 31, 32]. An extensive review of the biotechnological applications of antibody fragments has been given earlier [33, 34]. Plant expressed antibodies are also used in studying the basic metabolism of plants in terms of disease resistance against a pathogen, protein–protein interactions or the specific role of an endogenous protein in a metabolic process by selectively modulating its activity [35].

Advantages of Antibody Fragments and Biopharming

Expression of mAbs in heterologous production systems is precarious as the biological activity of the resultant molecule is dependent on several post-translational modifications. Biosynthesis of conventional antibody molecules (150 kDa), through the mammalian expression system and transgenic animals is highly expensive and time-consuming [27, 36]. The scFvs are smaller in size (~ 30 kDa) with less post-translational modifications. They show a similar specificity and affinity of the parental antibody against the antigen. Due to the smaller size, scFvs show a rapid blood clearance (a useful property in the radiotherapy and other diagnostic applications) and better tissue penetration (which has greater impact when they are used as therapeutics) than the full length mAbs [37–42]. Due to the rapid blood clearance, the in vivo availability of scFv is low compared to the mAbs, which is considered as the major drawback of scFv. In order to increase the bioavailability of scFv in the bloodstream, the diabodies (~ 55 k Da), triabodies (~ 85 kDa) and tetrabodies (~ 120 kDa) were developed by manipulating the length of the linker peptide in between the VH and VL domains [22, 43] or by using the methods which facilitate the multimerization of scFv molecules [7, 23, 44] (Fig. 1). Tandem dimerization of the scFv generated from two different antibody sources can also create a bispecific antibody by the variation in the arrangement of the VH and VL sequences [8, 9, 45] and was proved to be an effective methods to detect specific cell types with fluorescence-tagged scFv dimers [46] (Fig. 1d). Further to that, the multivalency generated by combining the coding sequences of more than one scFv together with the multimerization is used to link different moieties (one may be targeting a cell surface receptor on a cancer cell and other bound to an anti-cancer drug) which facilitate the targeted delivery of the therapeutics to its site of action [47, 48] (Fig. 1f).

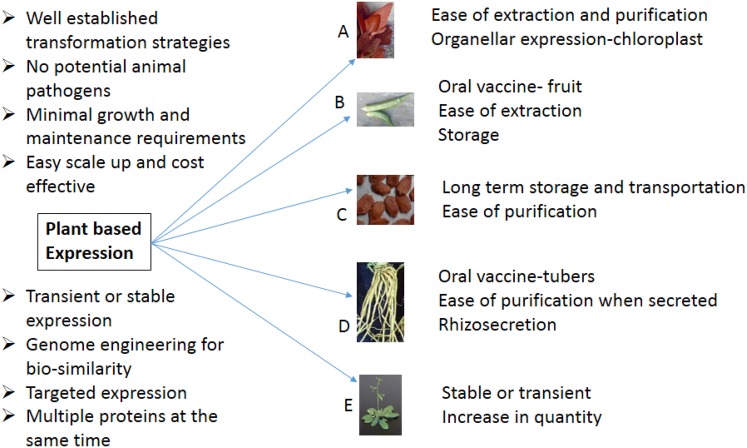

Considering the limitations of conventional expression systems like mammalian cells and prokaryotes, it is easy to manipulate the plants to cope with the mounting needs for a suitable recombinant protein production platform (Fig. 2). Contamination with an animal pathogen, one of the major concerns when using the mammalian expression system can be refuted if the plant expression systems are used. Farming of transgenic plants will open up the possibility of expanding the production of the target gene product with very little investment compared to the conventional methods. Targeted expression to seeds and the oil bodies serve a different function. When the protein need to be transported from its place of production or stored for longer, it can be expressed in seeds and for an easy purification, the proteins can be targeted to oil bodies [30, 49–51]. It is reported in the recent past that the plant-based expression systems are efficient to produce sufficient quantity of the recombinant antibodies transiently within a short time span especially during the epidemics like the recent Ebola virus outbreak in Africa [52, 53]. When using stably transformed plants like duckweeds with rapid multiplication rate as the biomanufacturing platform, the target protein can be expressed within a short period and the production can be increased as per the need [54]. The difference in post-translational modification patterns compared to that of mammalian cells has been taken care of in some of the model plants through genome engineering. Successful expression of antibodies, biologically and functionally similar to mammalian products is reported in few plants [16, 55–57]. Recently, Donini and Marusic reviewed extensively the plant-based antibody production platforms including bryophytes and algal species [58]. A comprehensive list of scFvs expressed in plants has been given in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Advantages of plant expression systems. Protein expression in leaves (a), fruit (b), seed (c), roots (d) and whole plant (e)

Table 1.

Transgenic plants expressing scFv/scFv varients

| S. nos | Model plant | Antigen | Antibody format | Transformation method | Expressed in | Protein yield | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Hepatitis A (HA78) and HIV (2G12) | scFv-Fc | Agrobacterium | Seeds, leaves | 0.8–9.4 mg/g dry wt | [112] |

| 2 | A. thaliana | Maltose Binding Protein (MBP 10), Hepatitis A (HA 78, HA 16) and Hantaan virus nucleocapsid protein (EHF 34) | scFv-Fc | Agrobacterium | Seed | 19–28 µg/mg seed | [49] |

| 3 | A. thaliana | Fungal mycotoxin Zearalenone | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [70] |

| 4 | A. thaliana | Human creatine kinase-MM (CK-MM) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 0.01% TSP | [29] |

| 5 | A. thaliana | human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) | scFv-Fc | Agrobacterium | Seeds | 1.1% TSP | [30] |

| 6 | A. thaliana | Herbicide Chloropropharm | scFv | Agrobacterium | Whole plant | – | [66] |

| 7 | A. thaliana | Gibberlin | scFv | Agrobacterium | Whole plant | – | [69] |

| 8 | A. thaliana | B-lymphocyte antigen CD20 | scFv-Fc | Agrobacterium | Seeds | 6.12% TSP | [81] |

| 9 | A. thaliana | Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α | scFv-Fc | Agrobacterium | Seeds | 0.27–0.46 mg/g seed | [79] |

| 10 | Chrysanthemum | PVX | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [152] |

| 11 | Hordeum vulgare | β-Lactoglobulin (BLG) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Seeds | 55 mg/kg grain | [80] |

| 12 | Kalanchoe pinnata | PVX | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [153] |

| 13 | Nicotiana benthamiana | Mouse B cell lymphoma, 38C13 | scFv | Virus | Leaves | – | [65] |

| 14 | N. benthamiana | tomato spotted wilt tospovirus (TSWV) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [32] |

| 15 | N. benthamiana | Glycoprotein G1 of Tomato spotted wilt virus | scFv | Agrobacterium | Whole plant | – | [68] |

| 16 | N. benthamiana | Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [154] |

| 17 | N. benthamiana | HER2 | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [155] |

| 18 | N. benthamiana | Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [156] |

| 19 | N. benthamiana | Beet necrotic yellow vein virus (BNYVV) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [157] |

| 20 | N. benthamiana | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [158] |

| 21 | N. benthamiana | Anti-rabis | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [132] |

| 22 | N. benthamiana | CD20 | scFv-Fc | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 28 mg/kg | [127] |

| 23 | N. benthamiana | CD20 | scFv-Fc | Agrobacterium | Hairy root | 16 mg/L | [18] |

| 24 | N. benthamiana | Metalloproteinase BaP1 | scFv | Agrobacterium | Suspension culture | 71.75 mg/L | [84] |

| 25 | N. benthamiana | Anti-CD20 2B8 (glyco-engineered) | scFv-Fc | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 20–35 mg/kg | [75] |

| 26 | N. benthamiana | Omp D |

scFv scFv-Fc |

Agrobacterium | Leaves | 45–82 µg/g | [93] |

| 27 | N. benthamiana | West Nile Virus (WNV) | scFv-CH | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [56] |

| 28 | N. benthamiana | WNV | scFv-CH (tetravalent) | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 0.8 mg/g | [159] |

| 29 | N. clevelandii | Porcine coronavirus transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 2% TSP | [145] |

| 30 | N. tabacum | Oxazolone (Ox), kresoxim-methyl (Kres) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Seeds | 0.5% TSP | [77] |

| 31 | N. tabacum | Fungal cutinase | scFv-SK, scFv-CK | Poly Ethylene Glycol | Leaves | [67] | |

| 32 | N. tabacum | Abscisic acid (ABA) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 0.05–4.8% TSP | [160] |

| 33 | N. tabacum | Paraquate, Atrazine | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 0.014% TSP | [161] |

| 34 | N. tabacum | Human RBC | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 2.9 to 3.28% TSP | [72] |

| 35 | N. tabacum | Cutinase of Botrytis cinerea |

scFv-SK scFv-CK |

Agrobacterium PEG | Leaves | 0.01–1% | [162] |

| 36 | N. tabacum | Hapten oxazolone | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 0.67% TSP | [163] |

| 37 | N. tabacum | Phytochrome | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [164] |

| 38 | N. tabacum | Hepatitis B surface antigen | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 0.031–0.22% TSP | [111] |

| 39 | N. tabacum | Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) movement protein (NSM) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 5.9–8% TSP | [73] |

| 40 | N. tabacum | Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [103] |

| 41 | N. tabacum | TMV | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 8.5 µg/g tissue | [165] |

| 42 | N. tabacum | Human tumor-associated antigen tenascin-C | scFv | Agrobacterium | Whole plant | – | [68] |

| 43 | N. tabacum | Picloram | scFv | Agrobacterium | Whole plant | – | [166] |

| 44 | N. tabacum | Salmonella enterica LPS | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 41.7 µg/g tissue | [167] |

| 45 | N. tabacum | Botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT/A) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Whole plant | 2 kg/Hector | [168] |

| 46 | N. tabacum | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (HER1) and HER 2 | scFv (bispecific) | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [9] |

| 47 | N. tabacum | Double stranded RNA | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [169] |

| 48 | N. tabacum | PVX | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [170] |

| 49 | N. tabacum | Tomato spotted wilt virus | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [171] |

| 50 | N. tabacum | T84.66 (From mouse human chimeric IgG1) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 15 µg/ml | [102] |

| 51 | N. tabacum | T84.66 (ScFv diabody) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [44] |

| 52 | N. tabacum | A. thaliana CDK | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 1.2–1.8%TSP | [90] |

| 53 | N. tabacum | Stolbur phytoplasma (mollicute) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | [115] | |

| 54 | N. tabacum | TMV (virion, coat protein) | scFv (bispecific) | Agrobacterium | Suspension culture | 0.0064–1.65 TSP | [8] |

| 55 | N. tabacum (BY2 cells) | Auxin Binding Protein (ABP1) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Cells | – | [83] |

| 56 | N. tabacum, Pisum sativum | Eimeria (oocysts, sporocysts and sporozoites) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves, seeds | 1.6–1.9 mg/g dry seed | [78] |

| 57 | N. tabacum | Human chronic gonadotropin HCG (β-subunit) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 20–40 mg/kg fresh leaf | [71] |

| 58 | N. benthamiana | β-1, 3-Glucan | scFv-Fc, VH + hHC, VL + hLC | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 40–60 mg/kg plant tissue | [92] |

| 59 | Oryza sps | E. coli, K-99 | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [172] |

| 60 | Petunia hybrida | Petunia dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves, flower | 0.3–1% TSP | [76] |

| 61 | Pisum sativum | Abscisic acid | scFv | Agrobacterium | Seeds | – | [106] |

| 62 | Solanum sps | Potato virus X (PVX) | scFv | Agrobacterium | Leaves | – | [74] |

| 63 | Solanum tuberosum | Fungal cutinase | scFv-CK, scFv-SK | Agrobacterium | Leaves | 0.02–0.1% TSP | [173] |

Col-0 plant-specific glycosylation knockout mutant TKO, scFv single chain variable fragment, VH variable heavy chain, VL variable light chain, hHC human heavy chain, hLC human light chain, scFv-SK scFv with an Endoplasmic reticulum targeting signal, scFv-CK scFv directed to cytoplasm, CK-MM creatine kinase with two subunits of the muscle type, RBC red blood cells, LPS lipopolysaccharide, CDK cyclin dependent kinase, CD 20 B-Lymphocyte antigen CD20 (Cluster of Differentiation), BaP1 Bothrops asper proteinase 1, biscFv bispecific scFv, OmpD outer membrane protein D, CH heavy chain constant domain

Transformation Methodologies, Target Plants and Expression of the Transgene

Among the methods employed for transformation of plant cells for scFv expression, Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer tops the list with more than 95% of representation in the reports. Transformation along with the genome editing techniques to modify the genome of the host plant to facilitate the protein expression in a tailor-made fashion has been the subject for a number of recent reviews [59–62]. In general, Agrobacterium tumefaciens transfer the T-DNA region from its Ti plasmid into the genome of the host plant, with the help of its vir gene products. Replacing the tumor-inducing genes with the gene(s) of interest (within the right and left borders), and co-cultivating the Agrobacterium containing the modified Ti plasmid with in vitro raised plant cells or wounded tissue leads to the transfer of cloned DNA into the plant cells followed by integration into the genome [62–64]. This method is cheap, easy to handle and produces transgenic lines carrying only one or a few copies of the transferred gene. While most of the transformation experiments using the model plants to express scFv followed the Agrobacterium-mediated gene transfer, there were reports on the use of plant virus [65] and polyethylene glycol [66, 67] as the method of transformation (Table 1).

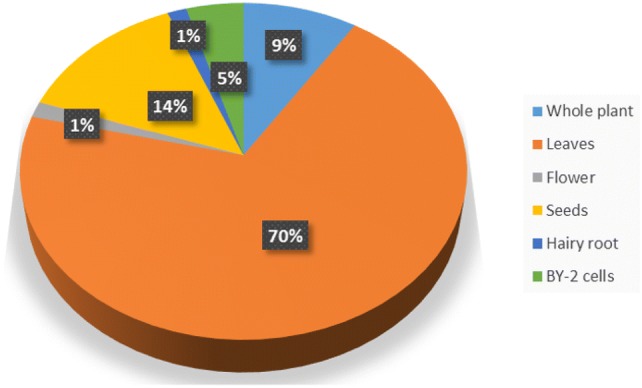

The model plants, Nicotiana (both tabacum and benthamiana sps), and Arabidopsis thaliana were the most favored expression systems for scFv (Fig. 3). Well-characterized in vitro propagation, transformation, and maintenance methods of these plants are the factors behind their selection. The protein was expressed in whole plant tissue [66, 68, 69], leaves [70–75], flower [76], seeds [77–81], hairy root culture [82] or tobacco BY-2 (tobacco cultivar Bright Yellow) cells [8, 83, 84] (Fig. 4). Even though there is a dearth of information about the level of expression either due to the lack of reports or due to the usage of measures which are difficult to compare (like TSP, µg/L, mg/kg and mg/Hector), the recent reports with standard measurements show that the model plants express proteins in good quantity [85]. In tobacco plants, exploitation of the hairy root formation for protein expression and rhizosecretion opens the possibilities of reducing the downstream processing cost of recombinant protein production. Developing specialized cell types like BY-2 or identifying the plants which have high multiplication potential can positively influence scFv production using plants. Another reason for using the model plants is the availability of genome engineered plants to support post-translational modification compatible with the mammalian expressed proteins [75]. Use of non-conventional plant groups such as algae and bryophytes, which were shown to be good protein expression platforms [58] can be an option for scFv expression.

Fig. 3.

Plants used for scFv expression

Fig. 4.

Tissue specific expression of scFv in plants

In plants, the heterologous expression of a gene can be transient or stable. In a stably transformed plant, the transgene is integrated into the genome and will pass on to the successive generations. The resultant product of the transgene continues to present throughout the plant body or in specific tissues (targeted expression). In transient expression, the transgene expresses the protein without a proper integration in to the genome and the transgene will not be transferred to the next generation. Vectors specifically designed for the transient expression of various target genes have been established [8, 86–88]. Agro-infiltration method was used commonly to establish transient transgenics. While most of the reports on scFv expression in plants deal with the generation of stable transgenics [29, 76, 89] there are few successful reports on the expression of biologically active scFv using the transient expression systems [65, 71, 90–92]. It was reported that compared to scFv-Fc format, the scFv format express better (a twofold increase) in N. benthamiana [93]. Nicotiana benthamiana hairy root culture was used successfully to express a glyco-engineered scFv antibody (CD20 2B8-Fc) based on the mAb Rituximab. Addition of the plant growth regulator 2,4-D was found to be enhancing the secretion of recombinant antibodies about 28-fold to the culture vessels. The purified CD20 2B8-Fc effectively bound to the CD20 antigen on the surface of human Daudi cells [18]. Transient expression is favored when the protein is needed within a short span of time in a comparatively large quantity [53, 93, 94] and for the expression of proteins which have an adverse effect on the host cells when over-expressed [95].

Promoters, Signal Peptides, and Targeted Expression

The use of different promoters in recombinant protein expression systems, in general, has been reviewed extensively [96–99]. The promoters used in heterologous expression systems vary significantly in their nature, activity, location, and mode of action. Studies revealed that in plants, the signal peptides and promoters are available to express, guide and store the protein in almost all cellular and extracellular targets [99]. Among the different types of promoters, the constitutive [100], and target specific [49, 50, 79, 101] promoters were used widely for scFv expression. The constitutive promoters CaMV35S [44, 78, 102, 103], Ubiquitin [51], and promoters of the seed storage proteins, globulins, glutelins, albumins, prolamins, and few other proteins like Sucrose binding protein [104], Unknown Seed Protein [77, 105, 106], and oleosin [107, 108] are used with or without the signal peptides for targeted expression and storage of heterologous proteins in transgenic plants. Yamamoto et al. reported the combination of a geminivirus replication sequence along with a double terminator in the transient protein expression vectors resulted in a twofold increase in the protein level compared to the transient expression using single terminator [109].

One of the major disadvantages, when plants are used as an expression platform, is the plant-specific secondary modifications added on to the proteins, which may make them immunogenic and hence useless in many applications. Addition of plant-specific N-glycans takes place in the endoplasmic reticulum and in the Golgi apparatus. Preventing the protein from reaching these targets keeps the protein away from any modifications. It can be done mainly using two methods; (1) by using the glycosylation mutants developed in model plants such as Arabidopsis and Nicotiana to facilitate similar glycosylation as that of mammalian system [55, 89, 110], and (2) engineer the construct by incorporating a signal peptide which either retain the expressed protein in the ER [49] or target the protein to the external medium, apoplastic space or to a tissue. The KDEL signal sequence is used extensively in plant recombinant scFv expression to retain the protein in the ER lumen [49, 111–113]. ER retention in many occasions is found to be beneficiary as the protein expressed show higher stability and concentration in the ER [113]. The 2S2 signal peptide derived from Arabidopsis seed storage protein is commonly used in plants to target the scFv to seeds [29, 51, 79, 112, 114]. There are reports on the use of signal peptides like pectate lyase SP [115] and murine signal peptide MSP [51, 102] with the plant expression systems for the secretion of scFv expressed.

While the transient expression is performed mostly with leaves, stable transgenics direct the protein expression to specific tissues. Expression of recombinant protein in seeds is considered as a suitable strategy for scFv expression. The scFv targeted to oil bodies in seeds was purified with less difficulty [108]. The same study reported that in the seeds, the shelf life of scFv was also increased. The seed-specific promoters, Phaseolus vulgaris β-phaseolin [30, 49, 50, 79, 101], legumin B4 [77, 116] unknown seed protein [77] and oleosin [108] were used to target scFv to the seeds in model plants. Zakharov and co-workers studied the seed directed expression of reporter genes using four seed-specific promoters in different transgenic plants including tobacco, pea, narbon bean, and linseed. The study proposes to engineer the promoter to impart more specificity for either pollen or seed to refute the ambiguity in non-specific expression [117]. In another study, the scfv targeting the surface epitopes of the sheep gut nematode Trichostrongylus colubriformis was fused to a trimeric polyoleosin and expressed in Arabidopsis seeds using the seed-specific oleosin promoter. The fusion product was accumulated in the oil bodies to a range of nearly 0.9% of total seed protein, showed a similar expression profile as that of oleosin [108]. Gomes and co-workers used a SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier) fusion protein with a scFv against the metalloproteinase BaP1 (Bothrops asper P1) increased the protein expression in N. benthamiana [84]. The advantages of targeting the protein expression to seeds along with the technical details on expression strategies and the issues to be considered when the product is having a pharmaceutical application have been explained well in one of the pioneering reviews on the seed-specific expression of recombinant proteins [118].

Negative Effects on the Host System, Transgene Stability and Product Inconsistency

The expression of certain recombinant proteins in a heterologous system may cause minor to severe side effects to the host. This topic was studied well in the prokaryotic expression system compared to mammalian or plant expression systems. In prokaryotes, especially with the induced expression of recombinant proteins, the host cells are affected due to; (a) target protein [119, 120], (b) inducer [121], or c) the toxicity of expressed protein [31, 122]. There are few studies at the transcriptome level in plants that tried to relate the effect of transgene expression with the physiological and physical status of the transgenic plants and found that there are no major differences observed in transgenic plants compared to the non-transgenic control under the conditions used [123–125]. De Wilde and co-workers studied the effect of recombinant antibody expression in the transcriptome and proteome of A. thaliana seeds collected 13-day post-anthesis. The study revealed that there was an upregulation of genes corresponding to protein folding modification, translocation, vesicle transport, and protein degradation. It was observed that the production of a recombinant antibody in the ER triggers ER stress, causing disturbance of normal cellular homeostasis [95].

Compared to CHO (Chinese Hamster Ovary) expression system, it is difficult to predict the expression efficiency of proteins in model plant systems. For example, the quantity of protein (mg/kg fresh tissue) expressed in N. benthamiana leaves vary from 28 mg/kg (anti-CD20 scFv, [126] to 45–85 mg/kg (anti-OmpD scFv [93]. The 2.5-fold change observed with the same model system for two different target proteins can be due to multiple factors involving the codon usage, mRNA stability, and proteolysis that are reported in plant expression systems [127, 128]. The structure and specific characters of the protein play a crucial role in its stability within the host and proteolysis can be a mechanism adopted by the host to maintain its functional integrity. Various methods like protease inhibitors, supplementing the suspension culture medium with stabilizing agents, knocking down the protease encoding genes, subcellular targeting of recombinant proteins and the use of fusion proteins are the major strategies to reduce proteolysis [129]. In another report, when two formats of the scFv (scFv and scFv-Fc) against the OmpD protein of Salmonella typhimurium expressed in N. benthamiana, the scFv version showed a greater expression (85.5 µg/g) than the scFv-Fc (45.9 µg/g). More detailed studies are necessary to prove the structure/function-based target protein cleavage in the expression host.

Unlike the prokaryotic system, expression of the transgene in the successive generations is a matter of concern in higher organisms like animals and plants. The factors controlling the expression of transgenes in plants include its copy number, place of integration, physiological status of the target tissue, nature of the protein, sorting signals, and subcellular localization [79, 130, 131]. There are only a few reports which studied the expression of antibody/antibody fragments in the transgenic progenies for three or four generations. In one of these studies, the protein (anti-TNF alpha scFv) concentrations were 0.270 µg/g, 0.37 µg/g, and 0.46 µg/g for the 5-day, 10-day and 20-day old seeds, respectively in the T2 generation. The concentration of the protein in the T3 generation was more (0.501 ± 0.0785 mg/g), especially in the homozygous genotypes [79]. While the recent strategies are targeted for transient expression, the tissue-based approach may be adopted only to those proteins which need special care.

Inconsistency in biological efficacy is one of the major problems of biosimilar proteins expressed in plants. The Mak-33 scFv encoding gene was expressed in tobacco as cytoplasmic and ER-targeted protein. Measurement of the affinity of the scFv with the antigen indicated an 80% reduction compared to parental Fab [29]. The reducing environment of cytosol considered as non-favorable for the disulfide bond formation in the proteins. While the transient expression of scFv in tobacco protoplast resulted in the absence of a disulfide bond and reduced activity, the scFv expressed in the cytosol of stably transformed tobacco plants was with disulfide bonds and showed excellent biological activity [67]. In one of the recent study published by Phoolcharoen et al. on the transient expression of a scFv against the rabies virus alone or in conjugation with a central nervous system-specific peptide, they showed that mice infected with the virus when treated with the scFv and scFv-peptide, both the molecules could cross the blood–brain barrier and the scFv-peptide specifically bound to the target confirming the bioavailability of the scFv [132, 133].

Glycoengineering for the Mammalian Type of Glycosylation

The allergic reactions to glycoproteins lead to the production of IgE antibodies in human beings. There were many studies conducted in the past to link the presence of IgE antibodies in patients and use that information for the diagnosis or treatment of allergic diseases. Surprisingly, none of these studies indicated a clear correlation between the presence of IgE in blood and its clinical effects [134, 135]. Immunogenicity induced by plant-specific glycans is one of the main objections against plant-based production of biotherapeutics. Contrary to this argument, experimental evidence showed that the plant-specific glycans do not interfere with the immune system and at times it is rather beneficial [56, 136, 137]. The N-glycosylation pattern of plant glycoproteins is different from the animals. Plant-derived recombinant proteins with N-linked glycosylation have a terminal β 1, 2-xylose and core α 1, 3-fucose. β 1, 4-galactose and sialic acid residues are absent in plants [138, 139]. O-linked glycosylation is also different in both plants and animals [140]. Taliglucerase alfa (TGA) expressed in carrot cells is an acid beta-glucosidase used in the treatment of Gaucher disease. Rup and co-workers studied the immunogenic effects of TGA over one year among adult and pediatric patients. The results indicated that 8/63 patients developed anti-plant-glycan antibodies. The detailed study of various disease parameters showed that the treatment was as efficient as of any other enzyme replacement therapies used, and the safety indicators were well within limits [17]. This observation substantiated the results obtained by Landry and co-workers on the use of a plant-based H5N1 vaccine. According to the results, only 14.8% of the patients that receive the vaccine against avian H5N1 influenza developed serum antibodies against plant-specific sugars [94]. Positive effects of humanized glycosylation in plant-derived antibody are reported in the case of ZMapp. ZMapp is a cocktail of three mAbs expressed in glyco-engineered N. benthamiana used for the treatment of the Ebola virus [141]. The medicine was approved by the FDA for usage during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Phase II clinical trials in four countries have been completed for ZMapp in 2015 [142]. Other examples are the synthesis of idiotype-specific vaccines for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [143] and follicular lymphoma [144].

To synthesize mammalian biosimilar proteins glycosylation machinery of the host plant need to be manipulated. Glycosylation mutants developed in A. thaliana and other model plants for protein expression had similar glycosylation as that of mammalian cells [16, 18, 75]. Even though there were minor differences in the glycosylation, scFv expressed in A. thaliana showed biological effects similar to the parental antibody [56, 112]. In a phase-I clinical trial to assess the safety and immunogenicity of recombinant idiotype-specific scFvs developed against non-Hodgkins lymphoma in Nicotiana, McCormick and co-workers observed that the vaccine has induced an idiotype-specific immune response [144]. Monger and co-workers studied the effect of vaccinating piglets against gastroenteritis virus infection with different concentrations of scFv with or without an adjuvant. Both low and high doses of vaccine with or without an adjuvant did not make any significant adverse effects. They also reported that the difference in glycosylation did not impart immunogenicity [145]. Underglycosylation of the native proteins along with aberrant glycosylation of scFv was noticed when an anti-MBP 10 scFv was expressed in the glycosylation mutant (alg 3-2) of A. thaliana [89]. In another study, anti-HA 78 and anti-2G12 (Loose et al. 2011) and MBP-10, HA 78, HA16 and EHF 34 [49] were also had the altered glycosylation pattern on the scFv. Aberrant deposition of ER-specific chaperons was reported when the protein was targeted to the ER [49]. The anti-CD20 scFv-Fc expressed in N. benthamiana glyco-engineered for xylose/fructose N-glycosylation were devoid of plant-specific N-glycosylation. The biological activity studies with purified scFv-Fc exhibited an improved binding affinity compared to the non-engineered form of scFv and rituximab. Cytotoxicity induced through the antibody-dependent cell-mediated pathway and the complementary dependent pathway was strongly enhanced [18, 126]. The data indicate that the major factor which prevents the use of plant system is the cost associated with the downstream purification of the recombinant protein rather than the post-translational changes associated with plant expression. Developing an expression system that may secrete the protein to the medium makes the purification process easy, and will resolve this issue.

Making the Plant System More Industrial Friendly

Validation of the cost factor had been done with several recombinant proteins including mAbs to evaluate the feasibility to develop the process for commercial purposes. With the ever-increasing demand for antibody fragments in the commercial market, there will be a continuous search for more economically viable platforms for its production. In this regard, it is worthwhile to look into the plant expression system to establish a cost-effective production platform and search for the points of concern to rectify it. While the seed-based propagation of plants is time-consuming, transient expression of proteins in plants can be attained in a few days. In N benthamiana, the transient expression system generated the recombinant antibody against the influenza virus in a time-bound manner. The agro-infiltration method took less than a week including the time needed for downstream processing to get the purified antibody [94]. It indicates that once the transformation and purification methods are established with a production platform, the recombinant protein can be made at will whenever it is needed. This technology will have great significance during conditions like the sudden surge of seasonal epidemics such as H1N1 or Ebola.

The argument on the cost factor was the focus of many research papers published recently [85, 146–148]. Unlike the uniformity that exists among the microbial or mammalian expression systems in terms of its growth requirements, amount of protein expression, and the strategies adopted for purification, plant expression systems exhibit significant differences among themselves. Plants offer an option to select the site of expression (leaves, whole plant, seeds) type of system (hairy root, plant, suspension culture) and the purification methods. Therefore the studies failed to derive any conclusions in general as the expression systems they have looked in to were different in many aspects. Schillberg and co-workers observed that plant systems have a relatively low yield, inconsistent productivity, and inefficient large-scale downstream processing. In the tobacco chloroplast, GFP was expressed at a concentration of 4 mg/g FW and Cry2Aa2 at 5 ng/g FW. Tobacco BY2 cell-based expression produced GFP at around 270 µg/ml. The study estimated that the production cost of 1 g of human M12 antibody in Nicotiana was around 1137 EUROs. The results also have shown that 84% of the total process cost was on the downstream processes and the cultivation account for only 16% [85]. When the same antibody purified from BY-2 cells, 77% of the total process cost was on the downstream processing. They also observed that the production rate of BY-2 cells was 20-fold lower than the whole tobacco plants. Another study estimated that the production cost of an antibody using the plant expression platform is about 100 EURO/g [149]. According to some previous reports, in CHO cells, the production cost is around 180 EURO/g for an antibody [148] and sometimes it can be as low as 22 EURO/g [150]. According to Lim et al., the production cost for 1 g of a typical glycosylated protein using different expression systems such as Pichia pastoris, mammalian cells, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas fluorescens is around 148, 206, 588, and 129 USD, respectively [148]. Sugar profiles attached to proteins can influence the activity. Due to the less complex machinery than the mammalian cells, plants are more amenable for specific glycan modification.

Tuse and co-workers used SuperPro Designer modeling software to predict the techno-economic advantage of the plant expression system using human butyrylcholinesterase and cellulose, two enzymes with diverse origin and application. The study proposed significant cost advantages with the plant expression compared to the conventional production systems for the above-said candidate molecules [146]. Buyel reviewed the additional streams which can be incorporated with the plant production platforms to increase its commercial potential. Other than the target proteins, the biomass can further be exploited to improve the revenue. The side stream of plant-based processes can double the revenue depending on the additional products developed in an integrated approach [147]. Plants are again endowed with additional features like rhizosecretion, which has not yet been exploited to its full potential [151]. The secret is in the selection of correct expression platform which is fast-growing, easy to manipulate genetically, needs less maintenance cost and have the provision to reduce downstream processing costs.

Conclusions and Future prospectus

As the mAb expression is more complex, it may be possible to look for antibody fragments, which offer similar activity as that of the mAb. Heterologous expression of antibody fragments in plants can be an effective and low-cost strategy for its large-scale pharmaceutical production. The major concerns in this system like the development of stable transgenics, expression of the protein, purification of the protein, structural and functional similarity with the parental antibody, and scaling up of the production platform been studied in detail and measures to tackle issues related to each of these topics were developed. The added advantages like the absence of any animal pathogens, targeted expression in organelles/storage organs, long-term storage of expressed protein in the target tissue, feasibility for oral consumption, facilitated purification as in the case of oil body coupled expression, and development of genome-edited expression platforms make plant-made recombinant proteins more lucrative. With the high demand for therapeutic antibodies in human and veterinary therapeutics, the magnitude of production needs to be enhanced. Combining the advantages of the plant expression system along with the favorable features of antibody fragments over mAbs may pave the path to the rapid biosynthesis of antibody-based diagnosis/therapeutics, which will increase the availability of the product and may lead to making the usage affordable.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the support from the Centre for Advanced Study, Department of Botany, Banaras Hindu University. Varanasi, India.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Berger M, Shankar V, Vafai A. Therapeutic applications of monoclonal antibodies. American Journal of Medical Sciences. 2002;324(1):14–30. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrne H, Conroy PJ, Whisstock JC, O’Kennedy RJ. A tale of two specificities: Bispecific antibodies for therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Trends in Biotechnology. 2013;31(11):621–632. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng X, Shen Z, Mernaugh R. Recombinant antibodies and their use in biosensors. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2012;402(10):3027–3038. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5569-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird RE, Hardman KD, Jacobson JW, Johnson S, Kaufman BM, Lee SM, Whitlow M. Single-chain antigen-binding proteins. Science. 1988;242:423–426. doi: 10.1126/science.3140379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huston JS, Levinson D, Mudgett-Hunter M, Tai MS, Novotný J, Margolies MN, Crea R. Protein engineering of antibody binding sites: Recovery of specific activity in an anti-digoxin single-chain Fv analogue produced in Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 1988;85(16):5879–5883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libyh MT, Goossens D, Oudin S, Gupta N, Dervillez X, Juszczak G, Cohen JH. A recombinant human scFv anti-Rh(D) antibody with multiple valences using a C-terminal fragment of C4-binding protein. Blood. 1997;90:3978–3983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu M, Wang X, Yin C, Zhang Z, Lin Q, Zhen Y, Huang H. Targeting TNF-α with a tetravalent mini antibody TNF-TeAb. Biochemical Journal. 2007;406:237–246. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer R, Schumann D, Zimmermann S, Drossard J, Sack M, Schillberg S. Expression and characterization of bispecific single-chain Fv fragments produced in transgenic plants. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1999;262(3):810–816. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semenyuk EG, Stremovskiy OA, Edelweiss EF, Shirshikova OV, Balandin TG, Buryanov YI, Deyev SM. Expression of single-chain antibody-barstar fusion in plants. Biochimie. 2007;89(1):31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelly MP, Lee FT, Tahtis K, Power BE, Smyth FE, Brechbiel MW, Scott AM. Tumor targeting by a multivalent single-chain Fv (scFv) anti-Lewis Y antibody construct. Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2008;23(4):411–423. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2007.0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates A, Power CA. David vs. Goliath: The structure, function, and clinical prospects of antibody fragments. Antibodies (Basel) 2019 doi: 10.3390/antib8020028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yusibov V, Kushnir N, Streatfield SJ. Antibody production in plants and green algae. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2016;67:669–701. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-111812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streatfield SJ, Kushnir N, Yusibov V. Plant-produced candidate countermeasures against emerging and reemerging infections and bioterror agents. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2015;13(8):1136–1159. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters J, Stoger E. Transgenic crops for the production of recombinant vaccines and anti-microbial antibodies. Human Vaccines. 2011;7(3):367–374. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.3.14303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma JKC, Drake PMW, Christou P. The production of recombinant pharmaceutical proteins in plants. Nature Reviews (Genetics) 2003;4:794–805. doi: 10.1038/nrg1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox KM, Sterling JD, Regan JT, Gasdaska JR, Frantz KK, Peele CG, Dickey LF. Glycan optimization of a human monoclonal antibody in the aquatic plant Lemna minor. Nature Biotechnology. 2006;24(12):1591–1597. doi: 10.1038/nbt1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rup B, Alon S, Amit-Cohen B-C, Brill Almon E, Chertkoff R, Tekoah Y, Rudd PM. Immunogenicity of glycans on biotherapeutic drugs produced in plant expression systems—The taliglucerase alfa story. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10):e0186211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lonoce C, Marusic C, Morrocchi E, Salzano AM, Scaloni A, Novelli F, Donini M. Enhancing the secretion of a glyco-engineered anti-CD20 scFv-Fc antibody in hairy root cultures. Biotechnology Journal. 2019;14(3):e1800081. doi: 10.1002/biot.201800081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson DS, Wu J, Peluso P, Nock S. Improved method for pepsinolysis of mouse IgG1 molecules to F(ab′)2 fragments. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2002;260(1–2):29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi Y, Kim H, Kato K, Masuda K, Shimada I, Arata Y. Proteolytic fragmentation with high specificity of mouse immunoglobulin G mapping of proteolytic cleavage sites in the hinge region. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1995;181(2):259–267. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brinkmann U, Reiter Y, Jung SH, Lee B, Pastan I. A recombinant immunotoxin containing a disulphide stabilized Fv fragment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 1993;90:7538–7542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundaresan G, Yazaki PJ, Shively JE, Finn RD, Larson SM, Raubitschek AA, Wu AMJ. 124I-labeled engineered anti-CEA minibodies and diabodies allow high-contrast, antigen-specific small-animal PET imaging of xenografts in athymic mice. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2003;44(12):1962–1969. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kostelny SA, Cole MS, Tso JY. Formation of a bispecific antibody by the use of leucine zippers. Journal of Immunology. 1992;148:1547–1553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorgensen ML, Friis NA, Just J, Madsen P, Petersen SV, Kristensen P. Expression of single-chain variable fragments fused with the Fc-region of rabbit IgG in Leishmania tarentolae. Microbial Cell Factories. 2014;13:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jäger V, Büssow K, Wagner A, Weber S, Hust M, Frenzel A, Schirrmann T. High level transient production of recombinant antibodies and antibody fusion proteins in HEK293 cells. BMC Biotechnology. 2013;13:52. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunert R, Reinhart D. Advances in recombinant antibody manufacturing. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2016;100(8):3451–3461. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7388-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frenzel A, Hust M, Schirrmann T. Expression of recombinant antibodies. Frontiers in Immunology. 2013;4:217. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balaji P, Satheeshkumar PK, Krishnan V, Vijayalakshmi MA. Expression of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) single chain variable fragment (scFv) in Spirodela punctata plants transformed with Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry. 2016;63(3):354–361. doi: 10.1002/bab.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruyns AM, De Jaeger G, De Neve M, De Wilde C, Van Montagu M, Depicker A. Bacterial and plant produced scFv proteins have similar antigen-binding properties. FEBS Letters. 1996;386:5–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong Y, Li J, Yao N, Wang D, Liu X, Wang N, Jiang C. Seed-specific expression and analysis of recombinant anti-HER2 single-chain variable fragment (scFv-Fc) in Arabidopsis thaliana. Protein Expression and Purification. 2017;133:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sushma K, Vijayalakshmi MA, Krishnan V, Satheeshkumar PK. Cloning, expression, purification and characterization of a Single chain variable fragment specific to Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha in Escherichia coli. Journal of Biotechnology. 2011;156:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franconi R, Roggero P, Pirazzi P, Arias FJ, Desiderio A, Bitti O, Benvenuto E. Functional expression in bacteria and plants of an scFv antibody fragment against tospoviruses. Immunotechnology. 1999;4(3–4):189–201. doi: 10.1016/s1380-2933(98)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weisser NE, Hall JC. Applications of single-chain variable fragment antibodies in therapeutics and diagnostics. Biotechnology Advances. 2009;27(4):502–520. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmad ZA, Yeap SK, Ali AM, Ho WY, Alitheen NB, Hamid M. scFv antibody: Principles and clinical application. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/980250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edgue G, Twyman RM, Beiss V. Antibodies from plants for bionanomaterials. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2017;9:e1462. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geskin LJ. Monoclonal antibodies. Dermatologic Clinics. 2015;33(4):777–786. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokota T, Milenic DE, Whitlow M, Schlom J. Rapid tumor penetration of a single-chain Fv and comparison with other immunoglobulin forms. Cancer Research. 1992;52(12):3402–3408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chowdhury PS, Viner JL, Beers R, Pastan I. Isolation of a high-affinity stable single-chain Fv specific for mesothelin from DNA-immunized mice by phage display and construction of a recombinant immunotoxin with antitumor activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 1998;95:669–674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chames P, Regenmortel MV, Weiss E, Baty D. Therapeutic antibodies: Successes, limitations and hopes for the future. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2009;157(2):220–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monnier PP, Vigouroux RJ, Tassew NG. In vivo applications of single chain Fv (Variable Domain) (scFv) fragments. Antibodies. 2013;2(2):193–208. doi: 10.3390/antib2020193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vitaliti A, Wittmer M, Steiner R, Wyder L, Neri D, Klemenz R. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by a single-chain antibody directed against vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Research. 2000;60(16):4311–4314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ronca R, Benzoni P, Leali D, Urbinati C, Belleri M, Corsini M, Dell’Era P. Antiangiogenic activity of a neutralizing human single-chain antibody fragment against fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2010;9:3244–3253. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Gall F, Kipriyanov SM, Moldenhauer G, Little M. Di-, tri- and tetrameric single chain Fv antibody fragments against human CD19: Effect of valency on cell binding. FEBS Letters. 1999;453(1–2):1648. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00713-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaquero C, Sack M, Schuster F, Finnern R, Drossard J, Schumann D, Fischer R. A carcinoembryonic antigen-specific diabody produced in tobacco. FASEB Journal. 2002;16:408–410. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0363fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hornig N, Färber-Schwarz A. Production of bispecific antibodies: Diabodies and tandem scFv. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2012;907:713–727. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-974-7_40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallo E, Snyder AC, Jarvik JW. Engineering tandem single-chain Fv as cell surface reporters with enhanced properties of fluorescence detection. Protein Engineering Design and Selection. 2015;28(10):327–337. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzv016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Helfrich W, Haisma HJ, Magdolen V, Luther T, Bom VJ, Westra J, de Leij L. A rapid and versatile method for harnessing scFv antibody fragments with various biological effector functions. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2000;237(1–2):131–145. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kato T, Yui M, Deo VK, Park EY. Development of Rous sarcoma virus-like particles displaying hCC49 scFv for specific targeted drug delivery to human colon carcinoma cells. Pharmaceutical Research. 2015;32(11):3699–3707. doi: 10.1007/s11095-015-1730-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Droogenbroeck B, Cao J, Stadlmann J, Altmann F, Colanesi S, Hillmer S, De Jaeger G. Aberrant localization and underglycosylation of highly accumulating single-chain Fv-Fc antibodies in transgenic Arabidopsis seeds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 2007;104:1430–1435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609997104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Jaeger G, Scheffer S, Jacobs A, Zambre M, Zobell O, Goossens A, Angenon G. Boosting heterologous protein production in transgenic dicotyledonous seeds using Phaseolus vulgaris regulatory sequences. Nature Biotechnology. 2002;20:1265–1268. doi: 10.1038/nbt755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoger E, Vaquero C, Torres E, Sack M, Nicholson L, Drossard J, Fischer R. Cereal crops as viable production and storage systems for pharmaceutical scFv antibodies. Plant Molecular Biology. 2000;42:583–590. doi: 10.1023/a:1006301519427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hiatt A, Pauly M, Whaley K, Qiu X, Kobinger G, Zeitlin L. The emergence of antibody therapies for Ebola. Human Antibodies. 2015;23(3–4):49–56. doi: 10.3233/HAB-150284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosales-Mendoza S, Nieto-Gómez R, Angulo C. A perspective on the development of plant-made vaccines in the fight against Ebola virus. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017;8:252. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rival S, Wisniewski JP, Langlais A, Kaplan H, Freyssinet G, Vancanneyt G, Edelman M. Spirodela (duckweed) as an alternative production system for pharmaceuticals: A case study, aprotinin. Transgenic Research. 2008;17:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s11248-007-9123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strasser R, Stadlmann J, Schahs M, Stiegler G, Quendler H, Mach L, Steinkellner H. Generation of glycoengineered Nicotiana benthamiana for the production of monoclonal antibodies with a homogeneous human-like N-glycan structure. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2008;6:392–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lai H, He J, Hurtado J, Stahnke J, Fuchs A, Mehlhop E, Chen Q. Structural and functional characterization of an anti-West Nile virus monoclonal antibody and its single-chain variant produced in glycoengineered plants. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2014;12(8):1098–1107. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jutras PV, Marusic C, Lonoce C, Deflers C, Goulet M, Benvenuto E, Donin M. An accessory protease inhibitor to increase the yield and quality of a tumour-targeting mAb in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0167086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Donini M, Marusic C. Current state-of-the-art in plant-based antibody production systems. Biotechnology Letters. 2019;41(3):335–346. doi: 10.1007/s10529-019-02651-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krishna G, Singh BK, Kim EK, Morya VK, Ramteke PW. Progress in genetic engineering of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.)—A review. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2015;13(2):147–162. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cardi T, D’Agostino N, Tripodi P. Genetic transformation and genomic resources for next-generation precise genome engineering in vegetable crops. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2017;8:241. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doron L, Segal N, Shapira M. Transgene expression in microalgae—From tools to applications. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;7:505. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hiei Y, Ishida Y, Komari T. Progress of cereal transformation technology mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2014;5:628. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh RK, Prasad M. Advances in Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated genetic transformation of graminaceous crops. Protoplasma. 2016;253(3):691–707. doi: 10.1007/s00709-015-0905-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yadava P, Abhishek A, Singh R, Singh I, Kaul T, Pattanayak A, Agrawal PK. Advances in maize transformation technologies and development of transgenic maize. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2017;7:1949. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCormick AA, Kumagai MH, Hanley K, Turpen TH, Hakim I, Grill LK, Levy R. Rapid production of specific vaccines for lymphoma by expression of the tumor-derived single-chain Fv epitopes in tobacco plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 1999;96(2):703–708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eto J, Suzuki Y, Ohkawa H, Yamaguchi I. Anti-herbicide single-chain antibody expression confers herbicide tolerance in transgenic plants. FEBS Letters. 2003;550:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00871-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schouten A, Roosien J, Bakker J, Schots A. Formation of disulfide bridges by a single-chain Fv antibody in the reducing ectopic environment of the plant cytosol. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(22):19339–19345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pizzuti F, Daroda L. Investigating recombinant protein exudation from roots of transgenic tobacco. Environmental Biosafety Research. 2008;7:219–226. doi: 10.1051/ebr:2008020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Urakami E, Yamaguchi I, Asami T, Conrad U, Suzuki Y. Immunomodulation of gibberellin biosynthesis using an anti-precursor gibberellin antibody confers gibberellin-deficient phenotypes. Planta. 2008;228(5):863–873. doi: 10.1007/s00425-008-0788-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yuan Q, Hu W, Pestka JJ, He SY, Hart P. Expression of a functional antizearalenone single-chain Fv antibody in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2000;66:3499–3505. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3499-3505.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kathuria S, Sriraman R, Sack M, Pal R, Artsaenko O, Talwar GP, Finnern R. Efficacy of plant-produced recombinant antibodies against HCG. Human Reproduction. 2002;17:2054–2061. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.8.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dobhal S, Chaudhary VK, Singh A, Pandey D, Kumar A, Agrawal S. Expression of recombinant antibody (single chain antibody fragment) in transgenic plant Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi. Molecular Biology Reports. 2013;40(12):7027–7037. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2822-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang M-Y, Zimmermann S, Fischer R, Schillberg S. Generation and evaluation of movement protein-specific single-chain antibodies for delaying symptoms of Tomato spotted wilt virus infection in tobacco. Plant Pathology. 2008;57:854–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2008.01863.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang JG, Hwang KH, Kil EJ, Park J, Cho S, Lee YG, Lee S. PVX-tolerant potato development using a nucleic acid-hydrolyzing recombinant antibody. Acta Virologica. 2017;61(1):105–115. doi: 10.4149/av_2017_01_105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marusic C, Pioli C, Stelter S, Novelli F, Lonoce C, Morrocchi E, Donini M. N-glycan engineering of a plant-produced anti-CD20-hIL-2 immunocytokine significantly enhances its effector functions. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2018;115:565–576. doi: 10.1002/bit.26503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.De Jaeger G, Buys E, Eeckhout D, De Wilde C, Jacobs A, Kapila J, Depicker A. High level accumulation of single-chain variable fragments in the cytosol of transgenic Petunia hybrida. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1999;259:426–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scheller J, Leps M, Conrad U. Forcing single-chain variable fragment production in tobacco seeds by fusion to elastin-like polypeptides. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2006;4:243–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2005.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zimmermann J, Saalbach I, Jahn D, Giersberg M, Haehnel S, Wedel J, Kipriyanov SM. Antibody expressing pea seeds as fodder for prevention of gastrointestinal parasitic infections in chickens. BMC Biotechnology. 2009;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yao N, Ai L, Dong YY, Liu XM, Wang DZ, Wang N, Jiang C. Expression of recombinant human anti-TNF-α scFv-Fc in Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2016 doi: 10.4238/gmr.15027726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ritala A, Leelavathi S, Oksman-Caldentey KM, Reddy VS, Laukkanen ML. Recombinant barley-produced antibody for detection and immunoprecipitation of the major bovine milk allergen, β-lactoglobulin. Transgenic Research. 2014;23(3):477–487. doi: 10.1007/s11248-014-9783-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang D, Ma J, Sun D, Li H, Jiang C, Li X. Expression of bioactive anti-CD20 antibody fragments and induction of ER stress response in Arabidopsis seeds. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2015;99(16):6753–6764. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lonoce C, Salem R, Marusic C, Jutras PV, Scaloni A, Salzano AM, et al. Production of a tumor-targeting antibody with a human compatible glycosylation profile in N. benthamiana hairy root cultures. Biotechnology Journal. 2016;11:1209–1220. doi: 10.1002/biot.201500628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.David KM, Couch D, Braun N, Brown S, Grosclaude J, Perrot-Rechenmann C. The auxin-binding protein 1 is essential for the control of cell cycle. Plant Journal. 2007;50:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gomes M, Alvarez MA, Quellis LR, Becher ML, Castro JMA, Gameiro J, de Oliveira SM. Expression of an scFv antibody fragment in Nicotiana benthamiana and in vitro assessment of its neutralizing potential against the snake venom metalloproteinase BaP1 from Bothrops asper. Toxicon. 2019;160:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schillberg S, Raven N, Spiegel H, Rasche S, Buntru M. Critical analysis of the commercial potential of plants for the production of recombinant proteins. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2019;10:720. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Canto T. Transient expression systems in plants: Potentialities and constraints. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2016;896:287–301. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-27216-0_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mortimer CL, Dugdale B, Dale JL. Updates in inducible transgene expression using viral vectors: From transient to stable expression. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2015;32:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marsian J, Lomonossoff GP. Molecular pharming—VLPs made in plants. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2016;37:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Henquet M, Eigenhuijsen J, Hesselink T, Spiegel H, Schreuder M, van Duijn E, Bosch D. Characterization of the single-chain Fv-Fc antibody MBP10 produced in Arabidopsis alg3 mutant seeds. Transgenic Research. 2011;20(5):1033–1042. doi: 10.1007/s11248-010-9475-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eeckhout D, Fiers E, Sienaert R, Snoeck V, Depicker A, De Jaeger G. Isolation and characterization of recombinant antibody fragments against CDC2a from Arabidopsis thaliana. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2000;267:6775–6783. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2000.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McCormick AA, Reinl SJ, Cameron TI, Vojdani F, Fronefield M, Levy R, Tusé D. Individualized human scFv vaccines produced in plants: Humoral anti-idiotype responses in vaccinated mice confirm relevance to the tumor Ig. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2003;278(1):95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Capodicasa C, Chiani P, Bromuro C, De Bernardis F, Catellani M, Palma AS, Torosantucci A. Plant production of anti-β-glucan antibodies for immunotherapy of fungal infections in humans. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2011;9:776–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kopertekh L, Meyer T, Freyer C, Hust M. Transient plant production of Salmonella typhimurium diagnostic antibodies. Biotechnology Reports (Amsterdam) 2019;21:e00314. doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Landry N, Ward BJ, Trépanier S, Montomoli E, Dargis M, Lapini G, Vezina L. Preclinical and clinical development of plant-made virus-like particle vaccine against avian H5N1 influenza. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.De Wilde K, De Buck S, Vanneste K, Depicker A. Recombinant antibody production in Arabidopsis seeds triggers an unfolded protein response. Plant Physiology. 2013;161(2):1021–1033. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.209718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.De Muynck B, Navarre C, Boutry M. Production of antibodies in plants: Status after twenty years. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2010;8:529–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Marschall L, Sagmeister P, Herwig C. Tunable recombinant protein expression in E. coli: Promoter systems and genetic constraints. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2017;101(2):501–512. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-8045-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Leavitt JM, Alper HS. Advances and current limitations in transcript-level control of gene expression. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2015;34:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Park SH, Ong RG, Sticklen M. Strategies for the production of cell wall-deconstructing enzymes in lignocellulosic biomass and their utilization for biofuel production. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2016;14(6):1329–1344. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Peeters K, Wilde CD, Depicker A. Highly efficient targeting and accumulation of a Fab fragment within the secretory pathway and apoplast of Arabidopsis thaliana. European Journal of Biochemistry. 2001;268:4251–4260. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Morandini F, Avesani L, Bortesi L, Van Droogenbroeck B, De Wilde K, Arcalis E, Pezzotti M. Non-food/feed seeds as biofactories for the high-yield production of recombinant pharmaceuticals. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2011;9:911–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vaquero C, Sack M, Chandler J, Drossard J, Schuster F, Monecke M, Fischer R. Transient expression of a tumor-specific single-chain fragment and a chimeric antibody in tobacco leaves. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 1999;96:11128–11133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zimmermann S, Schillberg S, Liao YC, Fischer R. Intracellular expression of TMV-specific single-chain Fv fragments leads to improved virus resistance in Nicotiana tabacum. Molecular Breeding. 1998;4:369–379. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Heim U, Wang Q, Kurz T, Borisjuk L, Golombek S, Neubohn B, Wob U. Expression patterns and subcellular localization of a 52 kDa sucrose-binding protein homologue of Vicia faba (VfSBPL) suggest different functions during development. Plant Molecular Biology. 2001;7:461–474. doi: 10.1023/a:1011886908619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fiedler U, Filistein R, Wobus U, Bäumlein H. A complex ensemble of cis-regulatory elements controls the expression of a Vicia faba non-storage protein gene. Plant Molecular Biology. 1993;22:669–679. doi: 10.1007/BF00047407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Saalbach I, Giersberg M, Conrad U. High-level expression of a single chain Fv fragment (scFv) antibody in transgenic pea seeds. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2001;158:529–533. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lee WS, Tzen JT, Kridl JC, Radke SE, Huang AH. Maize oleosin is correctly targeted to seed oil bodies in Brassica napus transformed with the maize oleosin gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 1991;88:6181–6185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Winichayakul S, Pernthaner A, Livingston S, Cookson R, Scott R, Roberts N. Production of active single-chain antibodies in seeds using trimeric polyoleosin fusion. Journal of Biotechnology. 2012;161(4):407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.07.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yamamoto T, Hoshikawa K, Ezura K, Okazawa R, Fujita S, Takaoka M, Miura K. Improvement of the transient expression system for production of recombinant proteins in plants. Scientific Reports. 2018;8:4755. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23024-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Von Schaewen A, Sturm A, Oneill J, Chrispeels MJ. Isolation of a mutant Arabidopsis plant that lacks N-acetyl glucosaminyl transferase-I and is unable to synthesize Golgi-modified complex N-linked glycans. Plant Physiology. 1993;102:1109–1118. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ramirez N, Ayala M, Lorenzo D, Palenzuela D, Herrera L, Doreste V, Oramas P. Expression of a single-chain Fv antibody fragment specific for the hepatitis B surface antigen in transgenic tobacco plants. Transgenic Research. 2002;11:61–64. doi: 10.1023/a:1013967705337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Loose A, Van Droogenbroeck B, Hillmer S, Grass J, Pabst M, Castilho A, Steinkellner H. Expression of antibody fragments with a controlled N-glycosylation pattern and induction of endoplasmic reticulum-derived vesicles in seeds of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2011;155(4):2036–2048. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.171330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Petruccelli S, Otegui MS, Lareu F, Tran Dinh O, Fitchette AC, Circosta A, Beachy RN. A KDEL tagged monoclonal antibody is efficiently retained in the endoplasmic reticulum in leaves, but is both partially secreted and sorted to protein storage vacuoles in seeds. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2006;4:511–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2006.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.De Wilde C, De Neve M, De Rycke R, Bruyns A-M, De Jaeger G, Van Montagu M, Engler G. Intact antigen-binding MAK33 antibody and Fab fragment accumulate in intercellular spaces of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Science. 1996;114:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(96)04331-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Le Gall F, Bové JM, Garnier M. Engineering of a single-chain variable-fragment (scFv) antibody specific for the stolbur phytoplasma (mollicute) and its expression in Escherichia coli and tobacco plants. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 1998;64:4566–4572. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4566-4572.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hensel G, Floss DM, Arcalis E, Sack M, Melnik S, Altmann F, Conrad U. Transgenic production of an anti HIV antibody in the Barley endosperm. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0140476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zakharov A, Giersberg M, Hosein F, Melzer M, Muntz K, Saalbach I. Seed-specific promoters direct gene expression in non-seed tissue. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55(402):1463–1471. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Boothe J, Nykiforuk C, Shen Y, Zaplachinski S, Szarka S, Kuhlman P, Moloney MM. Seed-based expression systems for plant molecular farming. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2010;8:588–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Geertsma ER, Groeneveld M, Slotboom DJ, Poolman B. Quality control of overexpressed membrane proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of USA. 2008;105:5722–5727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802190105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Schlegel S, Klepsch M, Gialama D, Wickström D, Slotboom DJ, de Gier J. Revolutionizing membrane protein overexpression in bacteria. Microbial Biotechnology. 2010;3(4):403–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dvorak P, Chrast L, Nikel PI, Fedr R, Soucek K, Sedlackova M, Damborsky J. Exacerbation of substrate toxicity by IPTG in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) carrying a synthetic metabolic pathway. Microbial Cell Factories. 2015;14:201. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0393-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hattab G, Moncoq K, Warschawski DE, Miroux B. Escherichia coli as host for membrane protein structure determination: A global analysis. Biophysical Journal. 2014;106(2 Suppl 1):46a. doi: 10.1038/srep12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Abdeen A, Schnell J, Miki B. Transcriptome analysis reveals absence of unintended effects in drought-tolerant transgenic plants overexpressing the transcription factor ABF3. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Pons E, Peris JE, Pena L. Field performance of transgenic citrus trees: Assessment of the long-term expression of uidA and nptII transgenes and its impact on relevant agronomic and phenotypic characteristics. BMC Biotechnology. 2012;12:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-12-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gullì M, Salvatori E, Fusaro L, Pellacani C, Manes F, Marmiroli N. Comparison of drought stress response and gene expression between a GM Maize variety and a near-isogenic Non-GM variety. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0117073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Marusic C, Novelli F, Salzano AM, Scaloni A, Benvenuto E, Pioli C, Donini M. Production of an active anti-CD20-hIL-2 immunocytokine in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2016;14:240–251. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]