Abstract

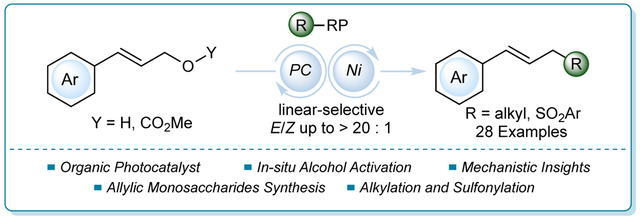

A radical-mediated functionalization of allyl alcohol-derived partners with a variety of alkyl 1,4-dihydropyridines via photoredox/nickel dual catalysis is described. This transformation transpires with high linear and E-selectivity, avoiding the requirement of harsh conditions (e.g., strong base, elevated temperature). Additionally, using aryl sulfinate salts as radical precursors, allyl sulfones can also be obtained. Kinetic isotope effect experiments implicated oxidative addition of the nickel catalyst to the allylic electrophile as the turnover-limiting step, supporting previous computational studies.

Graphical Abstract

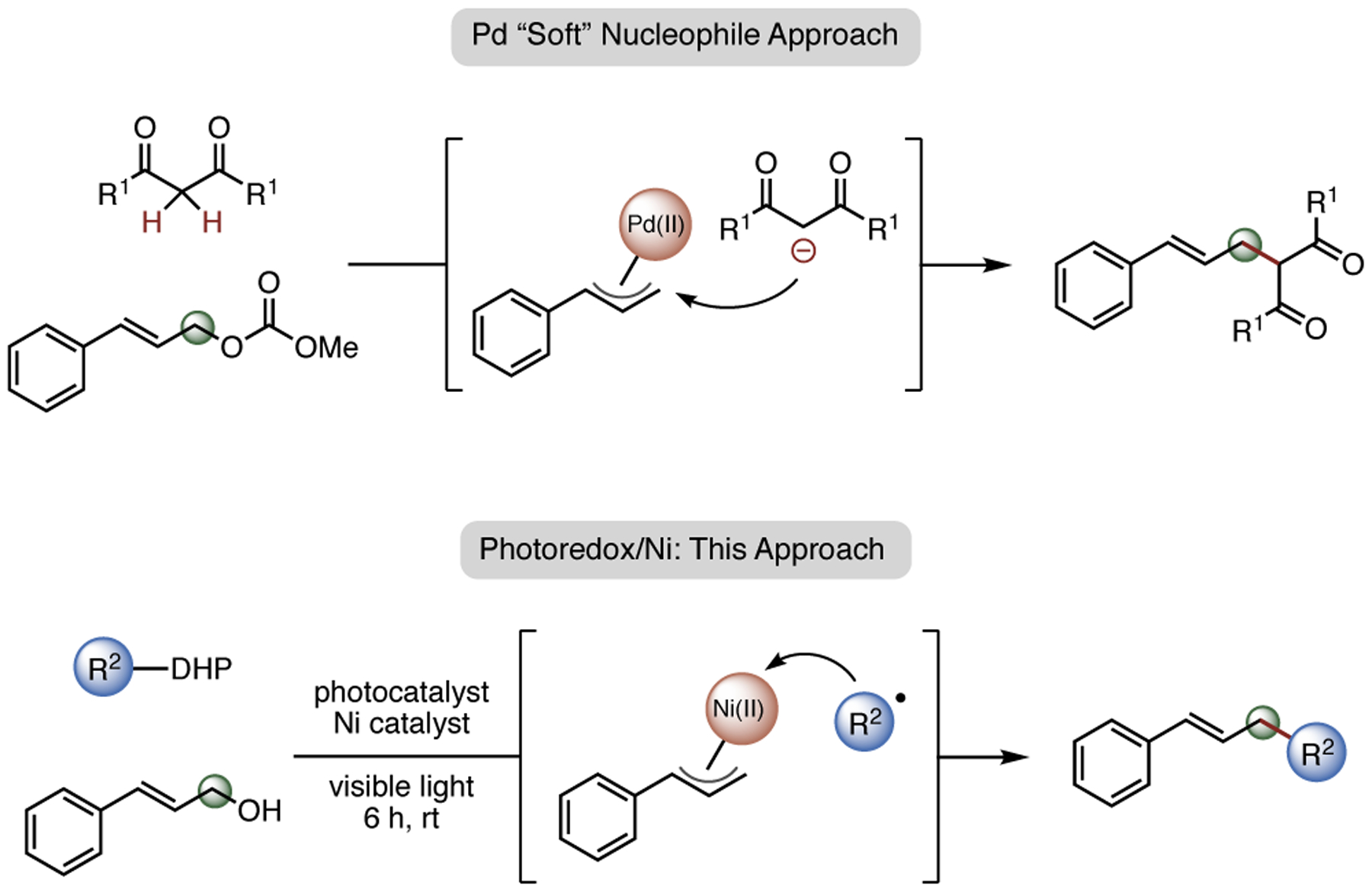

Historically, palladium catalysis has proven to be a powerful means by which C–C bonds can be forged in a regioselective manner.1 To date, there have been numerous reports utilizing palladium catalysis for coupling allyl alcohol substrates with “soft” (pKa < 25) enolate nucleophiles (Scheme 1).2 Other “soft” nucleophiles (e.g., nitrogen- and oxygen-based nucleophiles) have also been employed,3 and significant advances have been accomplished in the field with the development of stereoselective transformations. By comparison, although known, transformations using “hard” nucleophiles, which coordinate to metal catalysts before reductive elimination, are less studied and often require harsh conditions and/or functional group intolerant reagents.4 In an effort to expand the nucleophile scope of the Tsuji-Trost reaction, reductive allylation strategies have been explored by numerous groups, enabling the employment of “hard” nucleophiles.5 Notably, Tunge and coworkers pioneered the concept of a radical-based approach.5a In this paradigm, utilizing photoredox catalysis, the excited state photocatalyst undergoes a single-electron oxidation of a carboxylate anion substrate. Upon decarboxylation, a carbon-centered alkyl radical is generated and captured by a Pd(II) π-allyl complex, forming a Pd(III) intermediate that reductively eliminates to afford the cross-coupling product.

Scheme 1.

Radical-Based Addition to π-Allylnickel Intermediates

Although numerous coupling methods using various palladium catalysts have been reported during the past decades, significantly fewer methods have been disclosed utilizing the group 10 base metal, nickel.6 In addition to the advantage of cost-effectiveness, recent studies have shed light on the complementary reactivity that can arise between nickel and palladium. For example, Fu et al. successfully carried out nickel-catalyzed, enantioselective cross-coupling between allyl chlorides and alkylzinc reagents.7 Nickel/photoredox dual-catalyzed alkylation of vinyl epoxides have also been developed, with strong evidence of an inner-sphere mechanism.8

Inspired by previous work, a Ni-based radical approach to functionalize allylic electrophiles was sought. Herein, alkylation of allyl alcohol-derived motifs has been demonstrated by using 4-alkyl 1,4-dihydropyridines (DHPs)9 as latent radical precursors. Both allyl carbonates and in situ activated allyl alcohols have proven effective in the reaction. To highlight the new chemical space, the disclosed reaction was employed for the synthesis of allylated monosaccharides. Heteroatomic radical sources, such as aryl sulfinates, were also used as partners in this reaction. Finally, from a mechanistic standpoint, various factors influencing regioselectivity (e.g., the ligand on the nickel center) were demonstrated, in addition to kinetic isotope effect studies that support oxidative addition as the turnover-limiting step.

At the outset of the synthetic studies, optimization was conducted using isopropyl DHP as the radical precursor, and the best results were observed with allyl methyl carbonate as the electrophile. This result provided an opportunity to use dimethyl dicarbonate (DMDC) as an activator, which had proven to be compatible in previous studies (Table 1, entry 2).10 To confirm the necessity of photocatalyst 4CzIPN (2,4,5,6-tetrakis(carbazol-9-yl)-4,6-dicyanobenzene), nickel catalyst, and light, control experiments were performed (Table 1, entries 3–5). For each control experiment, no desired product was observed. Using high-throughput experimentation, further optimizations were carried out to identify a set of suitable reaction conditions (e.g., photocatalyst, Ni source, solvent and ligand, see Supporting Information for further details). To investigate the regioselectivity (linear/branched) and stereoselectivity (E/Z) of the reaction further, a series of bipyridine ligands were screened (entries 6–12). Most of the ligands led to highly selective linear product formation, although further investigations showed a substrate dependence on the linear/branched selectivity (see Supporting Information for further details). 1,10-Phenanthroline was identified as a suitable ligand, rendering almost exclusively E-selective product with a high yield (entry 6). Further reactions were therefore carried out using the preformed complex, Ni(phen)Cl2, as the precatalyst.

Table 1. Control Studies and Ligand Optimization.

Reaction conditions: Allyl alcohol or carbonate (1.0 equiv, 0.1 mmol), DHP (1.5 equiv, 0.15 mmol), 4CzIPN (3 mol %), Ni catalyst (5 mol %), DMDC (3.0 equiv), and DMF (0.1 M) thoroughly degassed followed by stirring near blue LEDs for 16 h. Overall yields and regioselectivity were determined by GC, and E/Z isomer ratios were determined by NMR.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | deviation from standard conditions | yield (%) | E/Z ratio (A:B) |

| 1 | R1 = CO2Me, R2 = i-Pr, No DMDC | 83 | > 20:1 |

| 2 | none, R2 = i-Pr | 66 | > 20:1 |

| 3 | no light, R2 = i-Pr | trace | - |

| 4 | no photocatalyst, R2 = i-Pr | 0 | - |

| 5 | no Ni catalyst, R2 = i-Pr | 0 | - |

| 6 | none, R2 = Cyclohexyl | 85 | > 20:1 |

| 7 | Ni 2, R2 = Cyclohexyl | 26 | 7:1 |

| 8 | Ni 3, R2 = Cyclohexyl | 66 | > 20:1 |

| 9 | Ni 4, R2 = Cyclohexyl | 8 | E only |

| 10 | Ni 5, R2 = Cyclohexyl | 10 | 1.3:1 |

| 11 | Ni 6, R2 = Cyclohexyl | 73 | 1:1.2 |

| 12 | Ni 7, R2 = Cyclohexyl | 21 | 2:1 |

| |||

With suitable conditions in hand, an investigation of the stereoelectronic effects of the aryl moiety on the reaction was begun. Similar to reactivity trends reported for Tsuji-Trost reactions,11 electron-withdrawing groups (2d) did not significantly decrease overall reaction efficiency. Conversely, electron-donating moieties (2e) led to slightly diminished yields (63%). Furthermore, exploration of alkyl-substituted electrophilic partners was of interest. Notably, 2f was successfully isolated from the corresponding dienol derivative, albeit in lower yield. As a general note, alkyl-substituted allyl carbonates suffered from diminished reactivity and, in some cases, no reactivity. This occurrence may result from a decrease in electrophilicity, hampering π-allyl nickel complex formation.

Next, attention was focused on incorporating a wider range of DHPs, beginning with cyclic carbon-centered radicals (2a, 2h and 2j). Functional groups such as alkenes (2g) and activated hydrogens (2i) are also compatible, providing good yields of the desired products. A 1 mmol scale reaction was also attempted for 1a, and a comparable 85% yield was obtained.

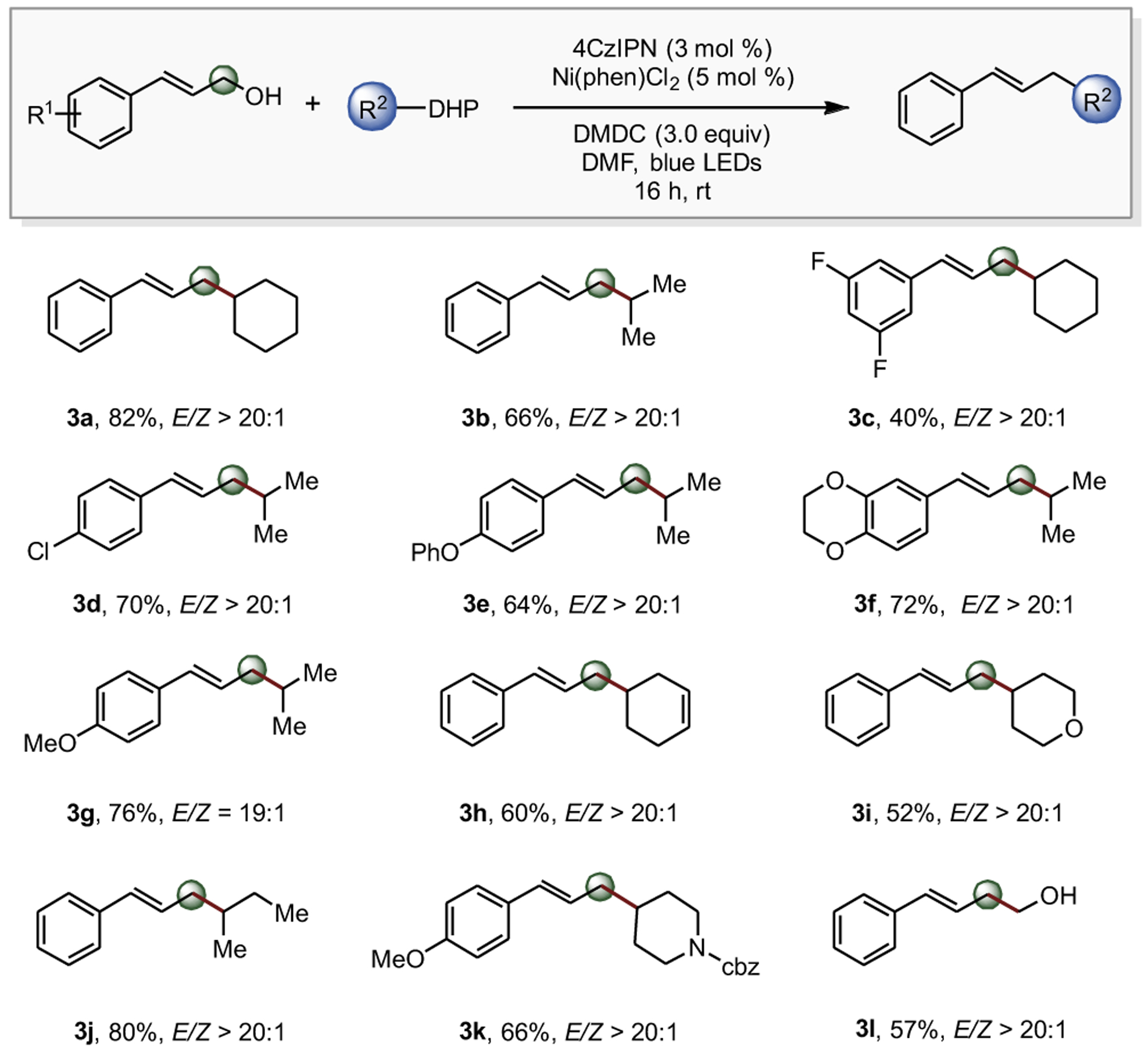

Although allyl carbonates are both commercially available and easily accessed, conditions were sought to improve step-economy by alkylating allylic alcohols in a single-step, one-pot reaction. With DMDC identified as the most efficient activator, the scope of this approach was examined with various cinnamyl alcohol derivatives and functionally diverse DHPs (Figure 1). Comparing previous yields with allyl carbonates and the newly developed allyl alcohol conditions, comparable results were achieved (2a and 2b versus 3a and 3b). Therefore, investigation of the scope of the functional group breadth for the allyl alcohol and DHP pieces was continued. Similar compatibility for substitutions about the aryl motif was observed (3c–3g). Nitrogen-(3k) and oxygen-containing (3i) heterocyclic DHPs were successfully incorporated into the reaction manifold, with moderate to good yield. Notably, a hydroxymethyl radical was successfully applied in this transformation, with a 57% yield of β-hydroxyl product 3l isolated.

Figure 1. Exploring Alkylation Scope with Carbonates.

Reaction conditions: Allyl methyl carbonate (1.0 equiv, 0.30 mmol), DHP (1.5 equiv, 0.45 mmol), 4CzIPN (3 mol %), Ni(phen)Cl2 (5 mol %), and DMF (3 mL, 0.1 M) thoroughly degassed followed by stirring near blue LEDs for 16 h. E/Z ratios were determined by 1H-NMR of the isolated product. a1 mmol scale. bdr > 20:1.

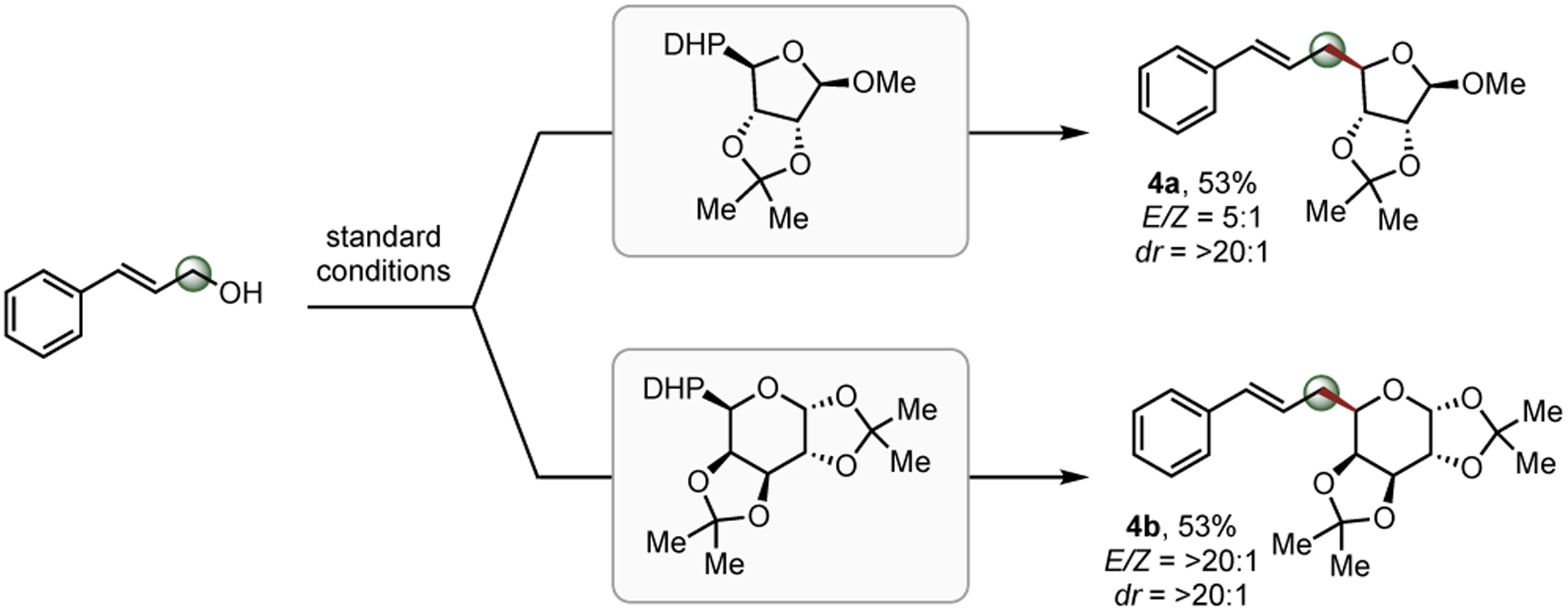

To broaden the scope and demonstrate the utility of this alkylation of allyl alcohol pro-electrophiles, attention was turned toward more challenging scaffolds, specifically monosaccharides.12 Functionalization of carbohydrates has proven to be pivotal in many fields, including labelling technologies,13 cyclodextrin-mediated catalysis,14 and carbohydrate drug development.15 Notably, few C-allyl glycoside syntheses have been reported, most of which are restricted to C-1 alkylation of the carbohydrate and further limited to unsubstituted propenyl electrophiles.16 Upon treating both furanose (4a) and pyranose (4b) DHPs under the standard reaction conditions, the non-traditional C-allyl glycosides were isolated in acceptable yields and excellent regio- and diastereoselectivities. Notably, structurally similar organometallic saccharide partners cannot be accessed owing to rapid β-alkoxy elimination. During the course of these studies, Mazet and coworkers published a complementary approach, using a one-pot isolation/C-O arylation strategy with a glycoside-derived allyl electrophile and Grignard reagents, rendering similar motifs albeit with less functional group tolerance anticipated in the aryl subunit.17

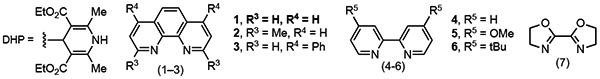

To extend the functional group repertoire of allyl alcohol-derived electrophiles further, other carbon- or heteroatom-centered radical sources were tested. Although toolboxes such as alkyltrifluoroborates,18alkylsilicates,19 and N-centered radicals20 were incompatible, aryl sulfinate salts were coupled with allyl carbonates to generate allyl aryl sulfones (Figure 3).21 Both electron-rich (5e) and electron-deficient (5c) allyl carbonates performed well, and an aliphatic allyl carbonate was applicable with good regioselectivity (5f), providing the desired product in 56% yield with a 9:1 E/Z ratio.

Figure 3. Demonstrating Latent Radical Breadth.

Reaction conditions: Allyl methyl carbonate (1.0 equiv, 0.30 mmol), DHP (1.5 equiv, 0.45 mmol), 4CzIPN (3 mol %), Ni(phen)Cl2 (5 mol %), and DMF (3 mL, 0.1 M) thoroughly degassed followed by stirring near blue LEDs for 16 h. E/Z ratios were determined by 1H-NMR of the isolated product. aSample was contaminated with hexane, EtOAc, and H2O.

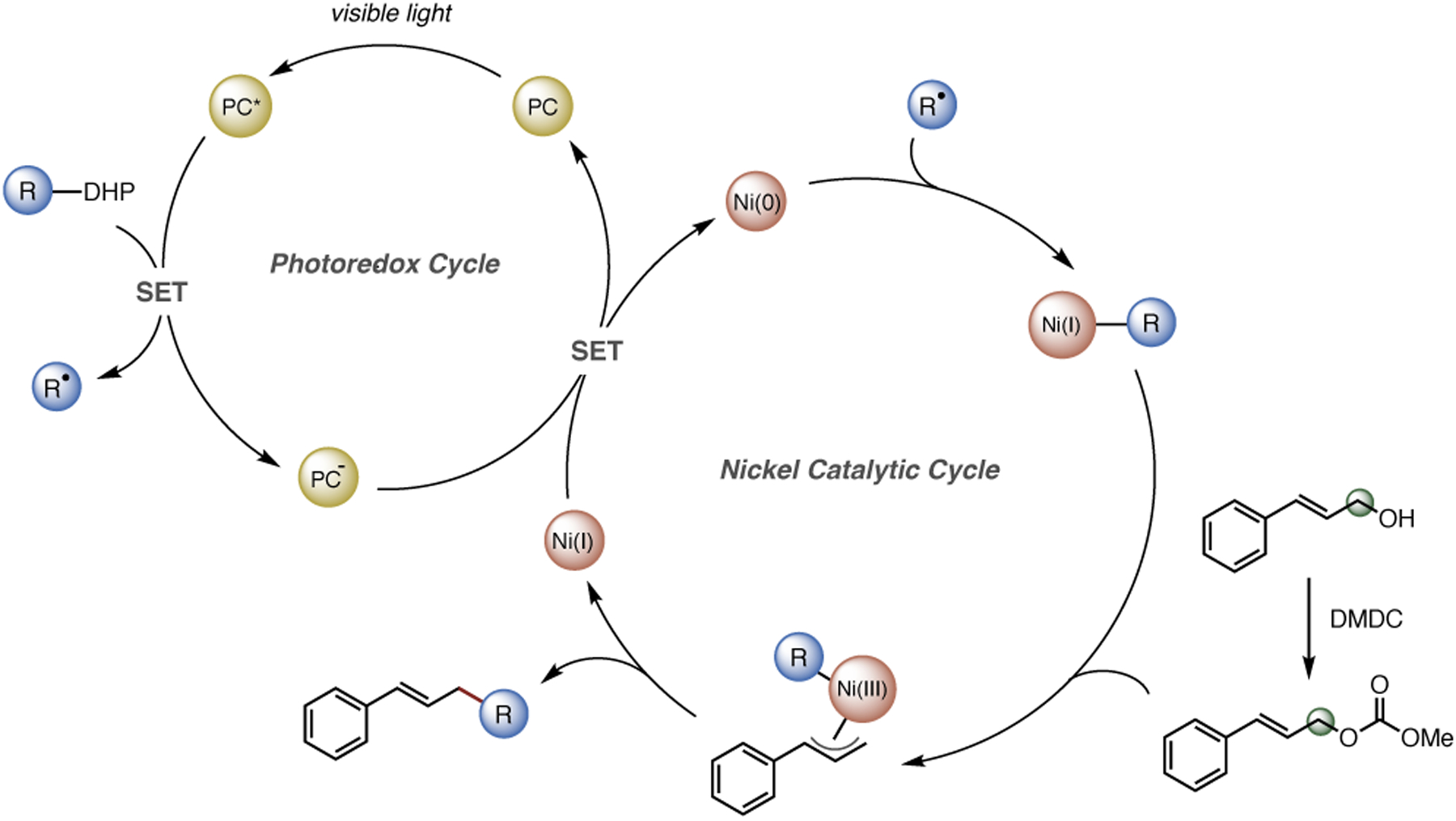

Finally, to shed some light on the mechanism, several preliminary experiments were carried out, including Stern-Volmer quenching experiments. Although significant fluorescent quenching with alkyl DHPs has been previously reported,22 neither Ni(phen)Cl2 nor allyl methyl carbonate quenched the fluorescence of 4CzIPN. This finding suggests that the reductive generation of the allylic radical is not occurring by interaction with the photocatalyst nor the low-valent Ni species. To determine the turnover-limiting step, we investigated the kinetic isotope effect by comparing reaction rates of α-deuterated cinnamyl methyl carbonate vs. its non-deuterated form. A significant secondary isotope effect (kH/kD = 1.15 ± 0.07) was observed, indicating a change in hybridization of the allyl carbonate substrate in the turnover-determining step, suggesting oxidative addition of allyl carbonate to the nickel complex as the turnover-limiting step. The regioselectivity would then most likely be dictated by energy differences between the corresponding transition structures involved in the reductive elimination step, which is consistent with previous computational studies.8,23 Based on these results and previous mechanistic studies, a plausible mechanism is proposed (Scheme 3): upon excitation, the photocatalyst oxidizes the radical precursors to generate alkyl- or sulfonyl radicals, which are subsequently captured by Ni(0). Allyl methyl carbonate then oxidatively adds to the Ni(I) intermediate to generate the active Ni(III) species, followed by reductive elimination to form Csp3-Csp3 or Csp3-S bonds. The resulting Ni(I) species is reduced by the radical anion of 4CzIPN, closing both catalytic cycles.

Scheme 3.

Putative Radical-Based Mechanism

In conclusion, the in-situ activation and radical-mediated alkylation of cinnamyl alcohol scaffolds in a photoredox/nickel-mediated transformation has been disclosed. During the course of these studies, reaction conditions (e.g., ligand, solvent) to favor the regioselective linear product and E-isomer have been pinpointed. Furthermore, the range of “nucleophilic” partners has been expanded. By either prefunctionalization or in situ activation with DMDC, radical precursors such as alkyl DHPs and aryl sulfinates can be engaged in the reaction, rendering alkylated or sulfonylated species in a highly stereoselective and regioselective manner. Notably, monosaccharide-derived DHPs have been coupled in the reaction to prepare non-traditional C-allylated glycosides. As a complementary approach for allyl-alkyl/sulfone coupling, the disclosed transformation extends the scope of allylic functionalization, while at the same time extending the range of Ni-catalyzed photoredox transformations, providing a useful synthetic tool for elaboration of readily available electrophilic partners.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2. Coupling Allyl Alcohols with DHPs.

Reaction conditions: Allyl alcohol (1.0 equiv, 0.30 mmol), DHP (1.5 equiv, 0.45 mmol), 4CzIPN (3 mol %), Ni(phen)Cl2 (5 mol %), DMDC (3.0 equiv, 0.90 mmol), and DMF (3 mL, 0.1 M) thoroughly degassed followed by stirring near blue LEDs for 16 h. E/Z ratios were determined by 1H-NMR of the isolated product.

Scheme 2. Direct Allylation of Monosaccharides.

Reaction conditions: Allyl alcohol (1.0 equiv, 0.30 mmol), DHP (1.5 equiv, 0.45 mmol), 4CzIPN (3 mol %), Ni(phen)Cl2 (5 mol %), DMDC (3.0 equiv, 0.90 mmol), and DMF (3 mL, 0.1 M) thoroughly degassed, followed by stirring near blue LEDs for 16 h. E/Z ratios were determined by 1H-NMR of the isolated product.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by NIGMS (R35 GM 131680). We thank the NIH (S10 OD011980) for supporting the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) Merck Center for High Throughput Experimentation, which funded the equipment used in screening efforts. Z-J. Wang acknowledges financial support from the Chinese Scholarship Council. We thank Dr. Charles W. Ross, III (UPenn) for help in HRMS data acquisition.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Detailed experimental procedures, mechanistic investigations, characterization data, and NMR spectra for new compounds (PDF)

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Biffis A; Centomo P; Del Zotto A; Zecca M, Pd Metal Catalysts for Cross-Couplings and Related Reactions in the 21st Century: A Critical Review. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 2249–2295; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Johansson Seechurn CCC; Kitching MO; Colacot TJ; Snieckus V, Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling: A Historical Contextual Perspective to the 2010 Nobel Prize. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2012, 51, 5062–5085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Negishi E; Matsushita H; Chatterjee S; John RA, Selective carbon-carbon bond formation via transition metal catalysis. 29. A highly regio- and stereospecific palladium-catalyzed allylation of enolates derived from ketones. J. Org. Chem 1982, 47, 3188–3190; [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM; Self CR, On the palladium-catalyzed alkylation of silyl-substituted allyl acetates with enolates. J. Org. Chem 1984, 49, 468–473; [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM; Van Vranken DL, Asymmetric Transition Metal-Catalyzed Allylic Alkylations. Chem. Rev 1996, 96, 395–422; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sha S-C; Zhang J; Carroll PJ; Walsh PJ, Raising the pKa Limit of “Soft” Nucleophiles in Palladium-Catalyzed Allylic Substitutions: Application of Diarylmethane Pronucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 17602–17609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Johannsen M; Jørgensen KA, Allylic Amination. Chem. Rev 1998, 98, 1689–1708; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ghosh R; Sarkar A, Palladium-Catalyzed Amination of Allyl Alcohols. J. Org. Chem 2011, 76, 8508–8512; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Butt NA; Zhang W, Transition metal-catalyzed allylic substitution reactions with unactivated allylic substrates. Chem. Soc. Rev 2015, 44, 7929–7967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Keinan E; Roth Z, Regioselectivity in organo-transition-metal chemistry. A new indicator substrate for classification of nucleophiles. J. Org. Chem 1983, 48, 1769–1772; [Google Scholar]; (b) Castanet Y; Petit F, Fonctionnalisation en position allylique d’olefine methylenique par action d’un reactif nucleophile sur leur complexe palladie. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 20, 3221–3222; [Google Scholar]; (c) Shukla KH; DeShong P, Studies on the Mechanism of Allylic Coupling Reactions: A Hammett Analysis of the Coupling of Aryl Silicate Derivatives. J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 6283–6291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Lang SB; O’Nele KM; Tunge JA, Decarboxylative Allylation of Amino Alkanoic Acids and Esters via Dual Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 13606–13609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen H; Jia X; Yu Y; Qian Q; Gong H Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Allylation of Tertiary Alkyl Halides with Allylic Carbonates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 13103–13106; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cui X; Wang S; Zhang Y; Deng W; Qian Q; Gong H Nickel-catalyzed reductive allylation of aryl bromides with allylic acetates. Org. Biomol. Chem 2013, 11, 3094–3097; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tan Z; Wan X; Zang Z; Qian Q; Deng W; Gong H Ni-catalyzed asymmetric reductive allylation of aldehydes with allylic carbonates. Chem. Comm 2014, 50, 3827–3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Rosen BM; Quasdorf KW; Wilson DA; Zhang N; Resmerita A-M; Garg NK; Percec V, Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Couplings Involving Carbon−Oxygen Bonds. Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 1346–1416; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Han F-S, Transition-metal-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reactions: a remarkable advance from palladium to nickel catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev 2013, 42, 5270–5298; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tasker SZ; Standley EA; Jamison TF, Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 2014, 509, 299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Son S; Fu GC, Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Negishi Cross-Couplings of Secondary Allylic Chlorides with Alkylzincs. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 2756–2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsui JK; Gutiérrez-Bonet Á; Rotella M; Alam R; Gutierrez O; Molander GA, Photoredox/Nickel-Catalyzed Single-Electron Tsuji–Trost Reaction: Development and Mechanistic Insights. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 15847–15851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutiérrez-Bonet Á; Tellis JC; Matsui JK; Vara BA; Molander GA, 1,4-Dihydropyridines as Alkyl Radical Precursors: Introducing the Aldehyde Feedstock to Nickel/Photoredox Dual Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 8004–8008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amani J; Molander GA, Direct Conversion of Carboxylic Acids to Alkyl Ketones. Org. Lett 2017, 19, 3612–3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiménez-Aquino A; Ferrer Flegeau E; Schneider U; Kobayashi S, Catalytic intermolecular allyl–allyl cross-couplings between alcohols and boronates. Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 9456–9458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudlicky T; Entwistle DA; Pitzer KK; Thorpe AJ, Modern Methods of Monosaccharide Synthesis from Non-Carbohydrate Sources. Chem. Rev 1996, 96, 1195–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue Z; Zhang E; Liu J; Han J; Han S, Bioorthogonal Conjugation Directed by a Sugar-Sorting Pathway for Continual Tracking of Stressed Organelles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 10096–10101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang B; Bols M, Artificial Metallooxidases from Cyclodextrin Diacids. Chem. - Eur. J 2017, 23, 13766–13775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barragan-Montero V; Awwad A; Combemale S; de Santa Barbara P; Jover B; Molès J-P; Montero J-L, Synthesis of Mannose-6-Phosphate Analogues and their Utility as Angiogenesis Regulators. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 1771–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Giannis A; Sandhoff K, Stereoselective synthesis of α- C-allyl-glycopyranosides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 1479–1482; [Google Scholar]; (b) Du Y; Linhardt RJ; Vlahov IR, Recent advances in stereoselective c-glycoside synthesis. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 9913–9959; [Google Scholar]; (c) Hu Y-J; Roy R, Cross-metathesis of N-alkenyl peptoids with O- or C-allyl glycosides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 3305–3308; [Google Scholar]; (d) Nolen EG; Kurish AJ; Wong KA; Orlando MD, Short, stereoselective synthesis of C-glycosyl asparagines via an olefin cross-metathesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 2449–2453; [Google Scholar]; (e) Patnam R; Juárez-Ruiz JM; Roy R, Subtle Stereochemical and Electronic Effects in Iridium-Catalyzed Isomerization of C-Allyl Glycosides. Org. Lett 2006, 8, 2691–2694; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) McGarvey GJ; LeClair CA; Schmidtmann BA, Studies on the Stereoselective Synthesis of C-Allyl Glycosides. Org. Lett 2008, 10, 4727–4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romano C; Mazet C, Multicatalytic Stereoselective Synthesis of Highly Substituted Alkenes by Sequential Isomerization/Cross-Coupling Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 4743–4750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Tellis JC; Primer DN; Molander GA, Single-electron transmetalation in organoboron cross-coupling by photoredox/nickel dual catalysis. Science 2014, 345, 433–436; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Primer DN; Karakaya I; Tellis JC; Molander GA, Single-Electron Transmetalation: An Enabling Technology for Secondary Alkylboron Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 2195–2198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jouffroy M; Primer DN; Molander GA, Base-Free Photoredox/Nickel Dual-Catalytic Cross-Coupling of Ammonium Alkylsilicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 475–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corcoran EB; Pirnot MT; Lin S; Dreher SD; DiRocco DA; Davies IW; Buchwald SL; MacMillan DWC, Aryl amination using ligand-free Ni(II) salts and photoredox catalysis. Science 2016, 353, 279–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Yue H; Zhu C; Rueping M, Cross-Coupling of Sodium Sulfinates with Aryl, Heteroaryl, and Vinyl Halides by Nickel/Photoredox Dual Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 1371–1375; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cabrera-Afonso MJ; Lu Z-P; Kelly CB; Lang SB; Dykstra R; Gutierrez O; Molander GA, Engaging sulfinate salts via Ni/photoredox dual catalysis enables facile Csp2–SO2R coupling. Chem. Sci 2018, 9, 3186–3191; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jiang H; Tang X; Xu Z; Wang H; Han K; Yang X; Zhou Y; Feng Y-L; Yu X-Y; Gui Q, TBAI-catalyzed selective synthesis of sulfonamides and β-aryl sulfonyl enamines: coupling of arenesulfonyl chlorides and sodium sulfinates with tert-amines. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry 2019, 17, 2715–2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z-J; Zheng S; Matsui JK; Lu Z; Molander GA, Desulfonative photoredox alkylation of N-heteroaryl sulfones – an acid-free approach for substituted heteroarene synthesis. Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 4389–4393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutierrez O; Tellis JC; Primer DN; Molander GA; Kozlowski MC, Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Photoredox-Generated Radicals: Uncovering a General Manifold for Stereoconvergence in Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 4896–4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.