Abstract

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is a coronavirus which causes severe diarrhea and fatal dehydration in piglets. In general, probiotic supplements could enhance recovery and protect piglets against enteric pathogens. Seven local lactic acid bacteria (LAB), (Ent. faecium 79N and 40N, Lact. plantarum 22F, 25F and 31F, Ped. acidilactici 72N and Ped. pentosaceus 77F) from pig feces were well-characterized as high potential probiotics. Cell-free supernatants (CFS) and live LAB were evaluated for antiviral activities by co-incubation on Vero cells and challenged with a pandemic strain of PEDV isolated from pigs in Thailand. Cell survival and viral inhibition were determined by cytopathic effect (CPE) reduction assay and confirmed by immunofluorescence. At 1:16, CFS dilution (pH 6.3–6.8) showed no cytotoxicity in Vero cells and was therefore used as the dilution for antiviral assays. The diluted CFS of all Lact. plantarum showed the antiviral effect against PEDV; however, the same antiviral effect could not be observed in Ent. faecium and Pediococcus strains. In competitive experiment, only live Lact. plantarum 25F and Ped. pentosaceus 77F showed CPE reduction in the viral infected cells to <50% observed field area. This study concluded that the CFS of all tested lactobacilli, and live Lact. plantarum (22F and 25F) and Pediococcus strains 72N and 77F could reduce infectivity of the pandemic strain of PEDV from pigs in Thailand on the target Vero cells.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12602-017-9281-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Antiviral activity, Cell-free supernatants, Lactic acid bacteria, Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, Probiotics

Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) is one of the highly contagious and concerning viral diseases in the pig industry. The disease not only causes fatal watery diarrhea in piglets, but also significant weight loss in pigs of all ages. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) is an RNA virus that belongs to the family Coronaviridae. The recent outbreaks and worldwide re-emergence of PEDV have been reported in several countries including the USA, China, Korea, and Thailand [1, 2]. Without the effective protective agents, the disease has led to great economic losses worldwide [3].

Recent experiments and clinical studies show that gut microbiota plays an active role in serving as a primary barrier against food-borne pathogens including viruses [4]. Probiotic bacteria can promote the host defense mechanisms and modulation of immune system, with the potential to enhance the antiviral activity [5, 6]. Among them, the group of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), including genera Lactobacillus spp., Pediococcus spp., and Enterococcus faecium, is generally used as probiotics in animal productions [7]. The failure in finding new antiviral substances without adverse side effects [8] and the benefits of probiotics treatment in patients with rotavirus (RV) and HIV-associated diarrhea have led to an increased interest in probiotic bacteria as antiviral inhibitors [9, 10]. Although many researches show the antiviral effects of LAB on several viral infections in humans and livestock [11–13], few studies report on antiviral activity using only cell-free supernatant against a classical strain of PEDV [8]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on antiviral activity using both cell-free supernatant (CFS) and live LAB cells against a pandemic strain of PEDV.

This study investigated the cytotoxicity and potential antiviral activity of selected LAB from pig feces in Thailand as protective agents against a pandemic strain of PEDV isolated from pigs in Thailand, in vitro. To determine the antiviral ability and attachment ability of the LAB strains, as well as the cytotoxicity of cell-free supernatants (CFS) to Vero cells, the study used both CFS and live LAB strains on Vero cell lines challenged with a pandemic strain of PEDV.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Virus

Vero cell line ATCC® CCL-81™ was maintained in Modified Eagle’s Medium (MEM) (Gibco™, MA, USA), supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco™, MA, USA), and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco™, MA, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. PEDV, a pandemic strain SBPED0211_1 (accession number: JQ966337), was propagated in Vero cells as described by Hofmann and Wyler [14]. For the antiviral assay, virus with 100 50% tissue culture infective dose (100 TCID50/mL) was determined by the Reed and Muench method [15].

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Experiments were carried out with three Lact. plantarum strains 22F (LC035101), 25F (LC035105) and 31F (LC035106), two Ent. faecium strains 79N (LC035103) and 40N (LC035104), Ped. pentosaceus 77F (LC035102), and Ped. acidilactici 72N (LC035107) selected from 60 fecal samples of antibiotic-free commercial and indigenous pigs based on in vitro probiotic properties. They were able to tolerate pH 2, pH 3, 0.3% ox gall, and grow at 45 °C with ≥104 CFU/mL, and were acceptable according to European Food Safety Authority on antimicrobial susceptibility. They were therefore characterized and identified by 26 phenotypic tests and 16S rDNA sequence analysis with ≥99% similarities towards the type strains (Supplementary Table 1 ). Prior to experimentations, bacterial strains were grown in Man Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England) for 48 h at 37 °C under anaerobic condition [16].

CFS Preparation for Cytotoxicity Assay and Measurement of Antiviral Activity

Bacterial culture supernatants were obtained from growing bacterial cultures (108 CFU/mL) in 30 mL MRS broth under anaerobic conditions for 24 h at 37 °C. Supernatants were collected, measured pH values and two-fold serially diluted with MEM (1:2 to 1:64). The supernatants were then filtered with 0.22 μm filter (Milipore Corp., Bedford, USA) to remove any remaining bacterial cells from interfering with the experiments [8].

Determination of Adhering LAB Strains

One hundred microliters of each LAB suspension in MEM (1 × 108 CFU/mL) was added in triplicate to confluent Vero cell monolayers in 24 well plates and incubated for 90 min at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. After the incubation, the Vero cells were fixed and stained according to Lin et al. (2006). The number of adhered LAB cells per Vero cell was determined by counting LAB cells on 100 Vero cells, in 15 randomly selected microscopic fields (magnification fold, ×100) [17].

Determination of Cytotoxicity by Neutral red Assay

The cytotoxicity of LAB CFS to Vero cells was determined by the neutral red assay modified from Borenfreund and Puerner [18]. Briefly, Vero cell monolayers incubated with LAB CFS for 4 days were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and added with 200 μL MEM containing 50 μg/mL neutral red dye. The plate was incubated, washed with formal-calcium, and added with 0.2 ml of an acetic acid-ethanol mixture. The plate was kept at room temperature until dissolution. The cell viability was determined by comparison of the absorbance values at 540 nm obtained for control wells (without CFS) and tested wells (with CFS). The cytotoxicity assay and the quantitative colorimetric assay were carried out on the same cell culture plate.

Antiviral Assay

Antiviral Effect of Bacterial Cell-Free Supernatants (CFS)

The two-fold dilutions (1:16 to 1:64) of LAB CFS in MEM and CFS adjusted to pH 7 by sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were added on the monolayer of Vero cell as incubation medium (100 μL/well) followed by PEDV challenge (100 TCID50/mL). CPE was determined using CPE scores after an additional 4-day incubation at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. PEDV infected Vero cells without CFS treatment were used as a positive control. Untreated, non-infected Vero cells were used as a negative control [8, 12]. CPE scores were adjusted by CPE area observed under a microscope as; +++ (>75% of observed field area), ++ (50–75% of observed field area), + (<50% of observed field area) and − (no CPE) as modified from Kumar et al. [19].

Co-Incubation of Bacteria and PEDV (Competition Assay)

One hundred microliters of each live LAB strain at 108 CFU/mL to 104 CFU/mL in MEM were simultaneously added to pre-washed Vero cell monolayers in 96 well plates and subsequently challenged with 100 μL of 100 TCID50/mL PEDV (the viral titer remained unchanged). The plates were further incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 4 days and observed for CPE. All the controls and CPE scores were as described above [12, 13].

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was used to confirm viral infection in Vero cells; the monolayers of Vero cells were washed with PBS and air-dried. Cells were fixed with 80% acetone for 15 min. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated PEDV nucleoprotein (NP) monoclonal antibody (Medgene Lab, South Dakota, USA) against PEDV was added to each well. Plates were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, washed with PBS, and examined under a fluorescent microscope BX51 with DP73 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical Analysis

The adhering LAB strains were done in triplicate and presented as means ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey-Kramer post-hoc comparison was performed to compare means among LAB strains using SPSS 14.0 for Windows. Differences with P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

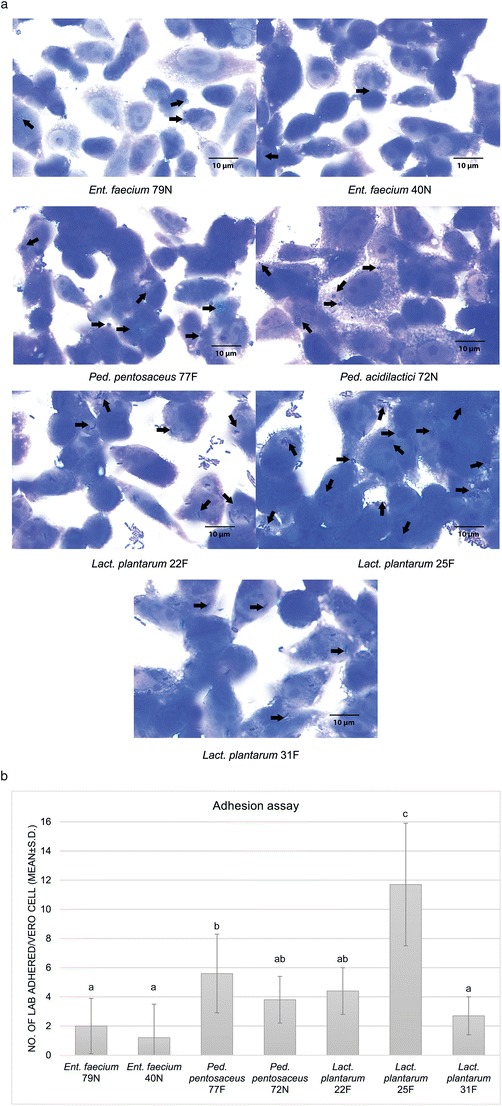

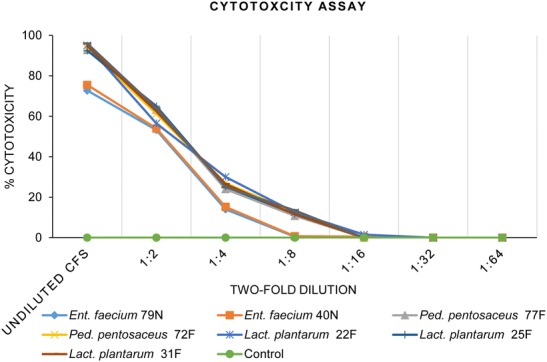

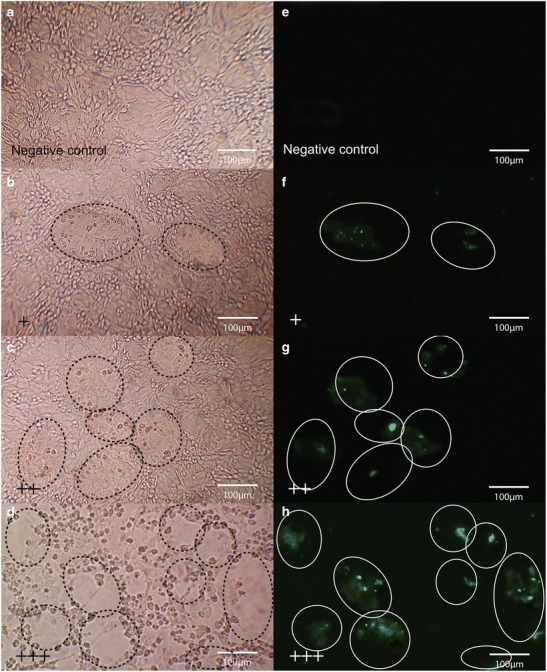

Seven LAB strains were preliminarily applied on the monolayers of Vero cell lines to ensure their adhesion ability (Fig. 1a). All LAB strains were able to adhere on the Vero cell, while Lact. plantarum strain 25F exhibited the highest adhesion ability (11.7%) (Fig. 1b). The cytotoxicity assay showed that at 1:16 to 1:64 CFS dilution of all LAB strains had no cytotoxicity to morphology of Vero cells (Fig. 2), and were used for the further antiviral assays. The antiviral effects of LAB CFS against PEDV on Vero cells was investigated by co-incubation with serial dilutions of CFS, and CFS adjusted to pH 7. After the co-incubation, the reduction of viral infectivity could be observed using CPE reduction assays and confirmed by qualitative immunofluorescence. A reduction of immunofluorescence signal indicated a decrease in PEDV infectivity in Vero cell monolayers (Fig. 3). The CFS of Lact. plantarum (22F, 25F, and 31F) at dilution 1: 16 were able to reduce the CPE and immunofluorescence signal to less than 50% observed field area (+) compared with only PEDV infected Vero cells (>75% observed field area, +++) (Table 1 and Fig. 3). In contrast, the CFS of Ent. faecium (79N and 40N) at dilution 1:16 exhibited no reduction of CPE and immunofluorescence signal. Moreover, at the dilution of 1:32 and 1:64 and adjusted pH 7, no reduction of viral infectivity was observed from all LAB strains (Table 1 and Fig.3).

Fig. 1.

a Adhesion ability of seven studied LAB strains on Vero cell monolayers. The observed magnification fold is ×100. The arrows indicate adhering bacterial cells. b Number of bacterial cells adhered per Vero cell. The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The different letters indicate statistically significant differences between LAB strains (P < 0.05)

Fig. 2.

The cytotoxicity evaluation by neutral red assay on Vero cell monolayers after exposure to undiluted and serially twofold dilutions (1:2 to 1:64) of CFS after day 4 of incubation

Fig. 3.

Antiviral activity of LAB against pandemic strain of PEDV on infected Vero cells. The CPE reduction was observed under a microscope at ×100. a No infection. b–d shows the CPE scores as + (<50% of observed field area), ++ (50–75% of observed field area), and +++ (>75% of observed field area). The reduction of the fluorescent signals of the infected cells were observed under a fluorescent microscope as e no infection; f–g shows the reduction signals scored as + (<50% of observed field area), ++ (50–75% of observed field area), and +++ (>75% of observed field area). The circles indicate the infectivity area

Table 1.

Antiviral activity against PEDV by cell-free supernatant (CFS) and seven live LAB strains on Vero cell monolayers as measured by the presence of CPE

| Bacterial strain | Supernatant dilution of LAB | Adjusted pH 7 | Bacterial concentration | Negative control | Positive control | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: 16 | 1: 32 | 1: 64 | 108 | 107 | 106 | 105 | 104 | ||||

| (~pH 6.3) | (~pH 6.6) | (~pH 6.8) | |||||||||

| Ent. faecium 79N | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ |

| Ent. faecium 40N | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ |

| Ped. pentosaceus 77F | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ |

| Ped. acidilactici 72N | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ |

| Lact. plantarum 22F | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ |

| Lact. plantarum 25F | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ |

| Lact. plantarum 31F | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | − | +++ |

Positive control: virus only; negative control: Vero cells only. CPE scores were adjusted by CPE area observed under a microscope as +++ (>75% of observed field area), ++ (50–75% of observed field area), + (<50% of observed field area), and − (no CPE)

Interestingly, at 106 CFU/mL in the competing experiment, only Lact. plantarum 25F exhibited CPE reduction to 50% of observed field area (++), and were able to reduce the viral infectivity to less than 50% observed field area (+) at 107 and 108 CFU/mL compared with the only PEDV infected Vero cells (+++). While Ped. Pentosaceus 77F and Lact. plantarum 22F at 107 CFU/mL were able to reduce the viral infectivity to 50% observed field area (++), only Ped. pentosaceus 77F at 108 CFU/mL displayed CPE reduction to less than 50% observed field area (+). In contrast, Ped. acidilactici 72N only exhibited CPE reduction at 108 CFU/mL to 50% of the observed field area. Furthermore, there were no reduction of CPE and immunofluorescence signal observed in any of the bacterial concentrations from Ent. faecium (79N and 40N) and Lact. plantarum 31F (Table 1).

Discussion

In this study, we observed the antiviral effects of CFS and live cells from seven local LAB strains against the pandemic strain of PEDV, in vitro. All LAB strains were well-characterized on the basis of probiotic properties including acid-bile tolerance, thermos-tolerance without a potential of forbidden antimicrobial resistant profile (supplementary Table 1). The pandemic strain of PEDV used in this study was propagated in Vero cell model. The viral strain was isolated from diseased pigs showing high morbidity and mortality; therefore, it would represent the true problematic issue in the field.

The low pH (pH 3.5 to 4.5) of LAB CFS [20] may directly impair the morphology of Vero cells. Our finding confirmed that at 1:16 dilution of CFS of all lactobacilli could reduce the CPE without cytotoxicity towards the Vero cells, but not with the higher dilutions. This might relate to the lower level of antiviral substances such as NO−, hydrogen peroxide, fatty acid, lactic acid, and acetic acid, in higher dilutions [12, 13, 21–23]. Furthermore, there were no antiviral effects observed from CFS adjusted to pH 7. Therefore, we assume that the inhibition of viral infectivity presented in this study might not be derived from bacteriocins, since it has been proven to also function at physiological pH [24]. Although, the accurate mechanisms of the antiviral effects from LAB CFS are still unclear, several studies have suggested possible explanations. Firstly, the acidity of CFS might help denaturing the viral capsid proteins and preventing them from cell attachment [25]. However, this might not apply for our study since we could not use the original pH of LAB CFS due to its toxicity towards the Vero cell. The more possible mechanism maybe the hindering and blocking of viral adsorption into the cells by CFS metabolites [26]. Therefore, the antiviral substances within CFS and their protective mechanisms will be investigated in further study.

The direct protective effect of live LAB cells to PEDV on Vero cells represented a possible scenario of probiotic feed supplements at the time of viral infection, without any cytotoxicity to normal Vero cell morphology. Lact. plantarum strain 25F showed the most antiviral efficacy by reduction of CPE on Vero infected cells. The minimum viable LAB concentration required to observe antiviral effects at 106 CFU/mL was in agreement with previous studies against rotavirus and gastroenteritis coronavirus, while the strongest effect was shown at 108 CFU/mL [12, 13, 25, 27, 28]. The decrease of viral infectivity in co-incubation assay could be explained by the competition for attachment to cell receptors between the bacterial cells and virus, the interference of viral attachment and cell entry, nonspecific or specific virus trapping, and the “cross-talk” signaling between LAB and the host cells which may alter the epithelial cells leading to antiviral responses [12, 25].

In conclusion, the CFS and live LAB in this study showed protective effects against the pandemic strain of PEDV in strain-specific manner. CFS of all tested lactobacilli could reduce viral infectivity in Vero cells, whereas other species lacked the ability. Live cells of Lact. plantarum strain 25F provided the greatest antiviral effects on reduction of CPE from the pandemic strain of PEDV. The preliminary study offered important findings for further studies for the extraction of antiviral compounds and the antiviral mechanisms of LAB with the virus and host.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 17 kb)

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by The 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Fund (Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund), STAR; Diagnosis and Monitoring of Animal Pathogen, Chulalongkorn University and the Agricultural Research Development Agency (ARDA) (No. 5803090002) (Public Organization), Thailand. We thank Professor Somboon Tanasupawat for assistance and comments to improve the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Shen H, Zhang C, Guo P, Liu Z, Zhang J. Effective inhibition of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus by RNA interference in vitro. Virus Genes. 2015;51(2):252–259. doi: 10.1007/s11262-015-1242-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee C. Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus: an emerging and re-emerging epizootic swine virus. Virol J. 2015;12(1):193. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0421-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di-qiu L, Jun-wei G, Xin-yuan Q, Yan-ping J, Song-mei L, Yi-jing L. High-level mucosal and systemic immune responses induced by oral administration with lactobacillus-expressed porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) S1 region combined with lactobacillus-expressed N protein. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2012;93(6):2437–2446. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3734-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acheson DW, Luccioli S. Microbial-gut interactions in health and disease. Mucosal immune responses. Best Pract Res Cl Ga. 2004;18(2):387–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaila M, Isolauri E, Saxelin M, Arvilommi H, Vesikari T. Viable versus inactivated lactobacillus strain GG in acute rotavirus diarrhoea. Arch Dis Child. 1995;72(1):51–53. doi: 10.1136/adc.72.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cross ML. Immunoregulation by probiotic lactobacilli: pro-Th1 signals and their relevance to human health. Clin Appl Immunol Rev. 2002;3(3):115–125. doi: 10.1016/S1529-1049(02)00057-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tannock GW. Probiotic properties of lactic-acid bacteria: plenty of scope for fundamental R & D. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15(7):270–274. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi H-J, Song J-H, Ahn Y-J, Baek S-H, Kwon D-H. Antiviral activities of cell-free supernatants of yogurts metabolites against some RNA viruses. Eur Food Res Technol. 2009;228(6):945–950. doi: 10.1007/s00217-009-1009-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang TL-Y, Chang C-H, Simpson DA, Xu Q, Martin PK, Lagenaur LA, Schoolnik GK, Ho DD, Hillier SL, Holodniy M. Inhibition of HIV infectivity by a natural human isolate of lactobacillus jensenii engineered to express functional two-domain CD4. P Natl A Sci. 2003;100(20):11672–11677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934747100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isolauri E. Probiotics for infectious diarrhoea. Gut. 2003;52(3):436–437. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.3.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chai W, Burwinkel M, Wang Z, Palissa C, Esch B, Twardziok S, Rieger J, Wrede P, Schmidt MFG. Antiviral effects of a probiotic Enterococcus faecium strain against transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus. Arch Virol. 2012;158(4):799–807. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1543-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Botić T, Danø T, Weingartl H, Cencič A. A novel eukaryotic cell culture model to study antiviral activity of potential probiotic bacteria. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;115(2):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maragkoudakis PA, Chingwaru W, Gradisnik L, Tsakalidou E, Cencic A. Lactic acid bacteria efficiently protect human and animal intestinal epithelial and immune cells from enteric virus infection. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;141:S91–S97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann M, Wyler R. Propagation of the virus of porcine epidemic diarrhea in cell culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26(11):2235–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.11.2235-2239.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed L, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C-Y, Lin P-R, Ng C-C, Shyu Y-T. Probiotic properties of Lactobacillus strains isolated from the feces of breast-fed infants and Taiwanese pickled cabbage. Anaerobe. 2010;16(6):578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin W-H, Hwang C-F, Chen L-W, Tsen H-Y. Viable counts, characteristic evaluation for commercial lactic acid bacteria products. Food Microbiol. 2006;23(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borenfreund E, Puerner JA. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol Lett. 1985;24(2):119–124. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(85)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo BJ, Mun MR, Kim C-J, Lee I, Kim H, Park Y-H. Putative probiotic Lactobacillus spp. from porcine gastrointestinal tract inhibit transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus and enteric bacterial pathogens. Trop Anim Health Pro. 2010;42(8):1855–1860. doi: 10.1007/s11250-010-9648-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fayol-Messaoudi D, Berger CN, Coconnier-Polter M-H, Lievin-Le Moal V, Servin AL. pH-, lactic acid-, and non-lactic acid-dependent activities of probiotic Lactobacilli against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(10):6008–6013. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.10.6008-6013.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ermolenko E, Furaeva V, Isakov V, Ermolenko D, Suvorov A. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 reproduction by probiotic bacteria in vitro. Vopr Virusol. 2009;55(4):25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saarela M, Mogensen G, Fonden R, Mättö J, Mattila-Sandholm T. Probiotic bacteria: safety, functional and technological properties. J Biotech. 2000;84(3):197–215. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(00)00375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dembinski JL, Hungnes O, Hauge AG, Kristoffersen A-C, Haneberg B, Mjaaland S. Hydrogen peroxide inactivation of influenza virus preserves antigenic structure and immunogenicity. J Virol Methods. 2014;207:232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang S-C, Lin C-H, Sung CT, Fang J-Y. Antibacterial activities of bacteriocins: application in foods and pharmaceuticals. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:241. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aboubakr HA, El-Banna AA, Youssef MM, Al-Sohaimy SA, Goyal SM. Antiviral effects of Lactococcus lactis on feline calicivirus, a human norovirus surrogate. Food Environ Virol. 2014;6(4):282–289. doi: 10.1007/s12560-014-9164-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allayeh AK, Dardeer EE, Kotb NS. Effects of cell-free supernatants of yogurts metabolites on Coxsackie B3 virus in vitro and in vivo. Middle East J Appl Sci. 2015;5:353–358. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charteris W, Kelly P, Morelli L, Collins J. Development and application of an in vitro methodology to determine the transit tolerance of potentially probiotic Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species in the upper human gastrointestinal tract. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;84(5):759–768. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee Y, Lim C, Teng W, Ouwehand A, Tuomola E, Salminen S. Quantitative approach in the study of adhesion of lactic acid bacteria to intestinal cells and their competition with enterobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(9):3692–3369. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.9.3692-3697.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 17 kb)