This cross-sectional study assesses the association of early Medicaid expansion with rates of Medicaid coverage, private insurance coverage, and no insurance among children with cancer.

Key Points

Question

Is early Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act associated with changes in private insurance, Medicaid, and no insurance coverage among children with cancer?

Findings

This cross-sectional study of 21 069 children aged 1 to 14 years used difference-in-differences analyses to demonstrate significantly increased Medicaid uptake (5.25%) and decreased private insurance (−4.52%) in states with early Medicaid expansion relative to nonexpansion states, particularly in regions of high poverty. Small reductions in uninsured rates (−0.73%) in expansion relative to nonexpansion states were also observed.

Meaning

This analysis found that state Medicaid expansion was associated with increased Medicaid coverage in children with cancer overall and in some subgroups, primarily due to switching from private coverage, but also through reductions in the uninsured.

Abstract

Importance

Despite evidence of improved insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid expansion among adults with cancer, little is known regarding the association of these policies with coverage among children with cancer.

Objective

To assess the association of early Medicaid expansion with rates of Medicaid coverage, private coverage, and no uninsurance among children with cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2015, to identify children diagnosed with cancer at ages 0 to 14 years in the United States. Data were analyzed from July 27, 2017, to October 7, 2019.

Exposures

Changes in insurance status at diagnosis after early Medicaid expansion in California, Connecticut, Washington, and New Jersey (EXP states) were compared with changes in nonexpansion (NEXP) states (Arkansas, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, New Mexico, and Utah).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Difference-in-differences (DID) analyses were used to compare absolute changes in insurance status (uninsured, Medicaid, private/other) at diagnosis before (2007 to 2009) and after (2011 to 2015) expansion in EXP relative to NEXP states.

Results

A total of 21 069 children (11 265 [53.5%] male; mean [SD] age, 6.18 [4.57] years) were included. A 5.25% increase (95% CI, 2.61%-7.89%; P < .001) in Medicaid coverage in children with cancer was observed in EXP vs NEXP states, with larger increases among children of counties with middle to high (adjusted DID estimates, 10.18%; 95% CI, 4.22%-16.14%; P = .005) and high (adjusted DID estimates, 6.13%; 95% CI, 1.10%-11.15%; P = .05) poverty levels (P = .04 for interaction). Expansion-associated reductions of children reported as uninsured (−0.73%; 95% CI, −1.49% to 0.03%; P = .06) and with private or other insurance (−4.52%; 95% CI, −7.16% to −1.88%; P < .001) were observed. For the latter, the decrease was greater for children from counties with middle to high poverty (−9.00%; 95% CI, −14.98% to −3.02%) and high poverty (−6.38%; 95% CI, −11.36% to −1.40%) (P = .04 for interaction).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, state Medicaid expansions were associated with increased Medicaid coverage in children with cancer overall and in some subgroups primarily owing to switching from private coverage, particularly in counties with higher levels of poverty but also through reductions in the uninsured.

Introduction

Each year, approximately 10 000 US children 14 years or younger receive cancer diagnoses, with approximately 1300 deaths due to cancer.1,2 Factors associated with worse childhood cancer outcomes include cancer type, first specialty consulted, older age, low socioeconomic status, and no insurance.3,4 However, unlike for adults, there is evidence of similar health care access5 and cancer survival6 among children regardless of whether the child’s insurance is public or private.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) allowed states to expand income eligibility for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Although most states expanded in 2014, some expanded in 2010 to 2011.7,8 Although the percentage of uninsured children has been declining recently, to date, approximately 5% still remain uninsured.9 A major risk factor for no insurance among children is noncontinuous coverage among their parents or guardians,10 with increasing evidence that expanding Medicaid coverage to parents and guardians leads to an increased percentage of children with Medicaid, a decreased percentage of uninsured persons,11,12,13,14 and increased use of health care services.15 However, the association of Medicaid expansion with Medicaid coverage in children with cancer has not been examined to date.

In children, diagnosis with or treatment for an illness, including cancer, triggers a presumptive and/or retrospective enrollment in Medicaid or CHIP for income-eligible children in most states. Parental job loss and financial hardship secondary to cancer diagnosis may also lead to Medicaid enrollment for eligible children. However, children in households with higher incomes, including those whose parents or guardians could buy CHIP coverage on a sliding scale, may remain uninsured or privately insured with considerable out-of-pocket expenses.16,17 Expanding Medicaid and CHIP coverage could therefore reduce financial hardship and associated stress due to a childhood cancer diagnosis.18 Expanding coverage could also have a positive association with earlier diagnosis, which may ultimately improve outcomes.6

Our objective was to quantify Medicaid expansion–associated changes in the percentage of children diagnosed with cancer with Medicaid or CHIP insurance, no insurance, and private or other insurance. As a secondary objective, we evaluated whether associations varied by sociodemographic and economic factors. We focused on Medicaid expansions occurring in 2010 to 2011, given 5 years of postexpansion data available in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, with supplementary analyses addressing the 2014 Medicaid expansions. Throughout this report, we use the term Medicaid expansion to include increases in CHIP eligibility and affordability.

Methods

Children aged 0 to 14 years and diagnosed with a first primary malignant neoplasm from January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2015, were identified in the SEER 18 database, covering approximately 28% of the US population.19 Because the data are deidentified and publicly available, the study was exempt from institutional review board oversight by Washington University in St Louis, and informed consent was not needed. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Cases diagnosed from January 1, 2010, through June 30, 2011, were excluded to correspond with early Medicaid expansion dates (April 1, 2010, to April 14, 2011) and to include a phase-in and washout period. We defined Medicaid and uninsured according to the any Medicaid and uninsured categories of the Insurance Recode (2007) variable and treated unknown insurance status as missing. Other insurance types were categorized as private or other.20 We used the SEER county attribute (American Community Survey, 2008-2012) variables to derive county educational (percentage of residents without high school education) and poverty (percentage of families below poverty) level groupings based on quartiles. We derived metropolitan residence status from the SEER 2013 Rural-Urban Continuum Code variable. For cancer type, we used the international classification of childhood cancer site recode International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition/World Health Organization 2008 variable.

Data were analyzed from July 27, 2017, to October 7, 2019. Data analyses were conducted in R software, version 3.3.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing). We performed multiple imputation using chained equations to estimate missing values for variables with missing data (eMethods in the Supplement).21 We used linear probability regression models applied to difference-in-differences (DID) analyses22 to compare changes in the percentage of children reported as having Medicaid, private or other insurance coverage, or no insurance at diagnosis based on person-level binary indicator variables (eg, 1 indicates Medicaid; 0, private or uninsured) before and after expansion between SEER registry states that expanded Medicaid early (California, Connecticut, New Jersey, and Washington [EXP states]) and those that did not (Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, New Mexico, and Utah [NEXP states]). The percentage insured (Medicaid plus private or other) DID estimates can be derived from the uninsured estimates by taking the opposite sign. The DID analyses were conducted for the overall population and by sociodemographic and economic strata. We used difference-in-difference-in-differences (DDD) to test for statistical differences in expansion-associated insurance changes between strata23 and the pairwise Wald test and multivariable extension of the Wald test to perform comparisons of the DDD between stratum levels.24 We evaluated the parallel trends assumption22 by restricting our analyses to 2007 and 2009 diagnoses and treating 2009 as the postintervention period. All analyses met this assumption unless otherwise indicated. We used heteroscedasticity robust standard errors in all regression models to account for potential correlation between individuals. Results are given as absolute percentage point (PP) changes. P values are 2 sided, with P < .05 considered statistically significant. To provide further context for evaluating the potential association of state Medicaid and CHIP eligibility limit changes on our results, we examined temporal changes in Medicaid and CHIP eligibility in children in EXP and NEXP states.25 Medians and study population–weighted means were calculated for each year. We performed several sensitivity analyses (eMethods in the Supplement), including a complete case analysis, removal of states expanding Medicaid in 2014 to 2015, removal of cases diagnosed in 2014 or later, and evaluation of the 2014 Medicaid expansions.

Results

Study Population

We identified a total of 25 339 children aged 0 to 14 years and diagnosed with a first primary malignant neoplasm from 2007 to 2015. After excluding 4270 observations to account for the phase-in and washout period, the analytic data set consisted of 21 069 children (11 265 [53.5%] male and 9804 [46.5%] female; mean [SD] age, 6.18 [4.57] years). Relative to EXP states, NEXP states had higher percentages of non-Hispanic white residents (4857 of 7833 [62.0%] vs 5328 of 13 236 [40.3%]) and lower percentages of Hispanic residents (973 of 7833 [12.4%] vs 5468 of 13 236 [41.3%]), metropolitan residents (6171 of 7833 [78.8%] vs 12 960 of 13 236 [97.9%]), residents with low county educational levels (1140 of 7833 [14.6%] vs 4859 of 13 236 [36.7%]), and residents in high-poverty counties (1373 of 7833 [17.5%] vs 3713 of 13 236 [28.1%]). In addition, NEXP states had lower percentages of leukemia cases (2226 of 7833 [28.4%] vs 4571 of 13 236 [34.5%]). Relative to before expansion, EXP and NEXP states had lower percentages of non-Hispanic white residents (EXP states, 3114 of 7849 [39.7%] vs 2214 of 5387 [41.1%]; NEXP states, 2908 of 4782 [60.8%] vs 1949 of 3051 [63.9%]) and higher percentages of female residents (EXP states, 3692 of 7849 [47.0%] vs 2269 of 4782 [47.4%]; NEXP states, 2269 of 4782 [47.4%] vs 1407 of 3051 [46.1%]) after Medicaid expansion (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Population by Expansion Status Before and After Expansion.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of participantsa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 21 069) | EXP states | NEXP states | |||

| Before expansion (n = 5387) | After expansion (n = 7849) | Before expansion (n = 3051) | After expansion (n = 4782) | ||

| Age, y | |||||

| <1 | 2071 (9.8) | 531 (9.9) | 701 (8.9) | 330 (10.8) | 509 (10.6) |

| 1-4 | 7427 (35.3) | 1930 (35.8) | 2762 (35.2) | 1083 (35.5) | 1652 (34.5) |

| 5-9 | 5463 (25.9) | 1388 (25.8) | 2091 (26.6) | 770 (25.2) | 1214 (25.4) |

| 10-14 | 6108 (29.0) | 1538 (28.6) | 2295 (29.2) | 868 (28.4) | 1407 (29.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 10 185 (48.3) | 2214 (41.1) | 3114 (39.7) | 1949 (63.9) | 2908 (60.8) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 1854 (8.8) | 516 (9.6) | 835 (10.6) | 181 (5.9) | 322 (6.7) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2317 (11.0) | 371 (6.9) | 527 (6.7) | 553 (18.1) | 866 (18.1) |

| Hispanic | 6441 (30.6) | 2230 (41.4) | 3238 (41.3) | 337 (11.0) | 636 (13.3) |

| Missing | 272 (1.3) | 56 (1.0) | 135 (1.7) | 31 (1.0) | 50 (1.0) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 11 265 (53.5) | 2951 (54.8) | 4157 (53.0) | 1644 (53.9) | 2513 (52.6) |

| Female | 9804 (46.5) | 2436 (45.2) | 3692 (47.0) | 1407 (46.1) | 2269 (47.4) |

| Metropolitan area of residence | |||||

| Nonmetropolitan | 1871 (8.9) | 106 (2.0) | 170 (2.2) | 623 (20.4) | 972 (20.3) |

| Metropolitan | 19 131 (90.8) | 5281 (98.0) | 7679 (97.8) | 2405 (78.8) | 3766 (78.8) |

| Missing | 67 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 23 (0.8) | 44 (0.9) |

| County educational levelb | |||||

| High | 4910 (23.3) | 997 (18.5) | 1528 (19.5) | 926 (30.4) | 1459 (30.5) |

| Middle to high | 4923 (23.4) | 1112 (20.6) | 1556 (19.8) | 894 (29.3) | 1361 (28.5) |

| Middle to low | 5232 (24.8) | 1296 (24.1) | 1888 (24.1) | 780 (25.6) | 1268 (26.5) |

| Low | 5999 (28.5) | 1982 (36.8) | 2877 (36.7) | 447 (14.7) | 693 (14.5) |

| Missing | 5 (0.02) | 0 | 0 | 4 (0.1) | 1 (0.02) |

| County poverty levelc | |||||

| High | 5086 (24.1) | 1501 (27.9) | 2212 (28.2) | 536 (17.6) | 837 (17.5) |

| Middle to high | 5441 (25.8) | 1499 (27.8) | 2126 (27.1) | 706 (23.1) | 1110 (23.2) |

| Middle to low | 4112 (19.5) | 763 (14.2) | 1153 (14.7) | 847 (27.8) | 1349 (28.2) |

| Low | 6425 (30.5) | 1624 (30.1) | 2358 (30.0) | 958 (31.4) | 1485 (31.1) |

| Missing | 5 (0.02) | 0 | 0 | 4 (0.1) | 1 (0.02) |

| Cancer site | |||||

| Leukemias, myeloproliferative diseases, and myelodysplastic diseases | 6797 (32.3) | 1857 (34.5) | 2714 (34.6) | 874 (28.6) | 1352 (28.3) |

| Lymphomas and reticuloendothelial | 2180 (10.3) | 554 (10.3) | 772 (9.8) | 328 (10.8) | 526 (11.0) |

| CNS and miscellaneous intracranial and intraspinal | 4289 (20.4) | 1075 (20.0) | 1504 (19.2) | 701 (23.0) | 1009 (21.1) |

| Neuroblastoma and other peripheral nervous cell | 1438 (6.8) | 346 (6.4) | 487 (6.2) | 237 (7.8) | 368 (7.7) |

| Renal | 1121 (5.3) | 294 (5.5) | 406 (5.2) | 151 (4.9) | 270 (5.6) |

| Retinoblastoma | 586 (2.8) | 125 (2.3) | 238 (3.0) | 101 (3.3) | 122 (2.6) |

| Hepatic | 389 (1.8) | 97 (1.8) | 147 (1.9) | 44 (1.4) | 101 (2.1) |

| Malignant bone | 963 (4.6) | 253 (4.7) | 343 (4.4) | 125 (4.1) | 242 (5.1) |

| Soft-tissue and other extraosseous sarcomas | 1449 (6.9) | 361 (6.7) | 517 (6.6) | 230 (7.5) | 341 (7.1) |

| Germ cell, trophoblastic, and gonads | 730 (3.5) | 193 (3.6) | 250 (3.2) | 110 (3.6) | 177 (3.7) |

| Other malignant epithelial and malignant melanomas | 1052 (5.0) | 210 (3.9) | 445 (5.7) | 143 (4.7) | 254 (5.3) |

| Other or unspecified | 75 (0.4) | 22 (0.4) | 26 (0.3) | 7 (0.2) | 20 (0.4) |

| Insurance | |||||

| Private or other | 12 294 (58.4) | 3528 (65.5) | 4510 (57.5) | 1736 (56.9) | 2520 (52.7) |

| Medicaid | 7728 (36.7) | 1685 (31.3) | 2982 (38.0) | 1154 (37.8) | 1907 (39.9) |

| Uninsured | 325 (1.5) | 81 (1.5) | 95 (1.2) | 50 (1.6) | 99 (2.1) |

| Missing | 722 (3.4) | 93 (1.7) | 262 (3.3) | 111 (3.6) | 256 (5.4) |

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; EXP, early expansion; NEXP, non–early expansion.

Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

Defined as percentage without high school educational attainment: less than 10.9% indicates high; 10.9% to 14.0%, middle to high; 14.1% to 20.7%, middle to low; and greater than 20.7%, as low.

Defined as percentage of families below poverty level: less than 7.65% indicates low; 7.65% to 10.14%, middle to low; 10.15% to 13.67%, middle to high; and greater than 13.67%, high.

Medicaid-Enrolled Children

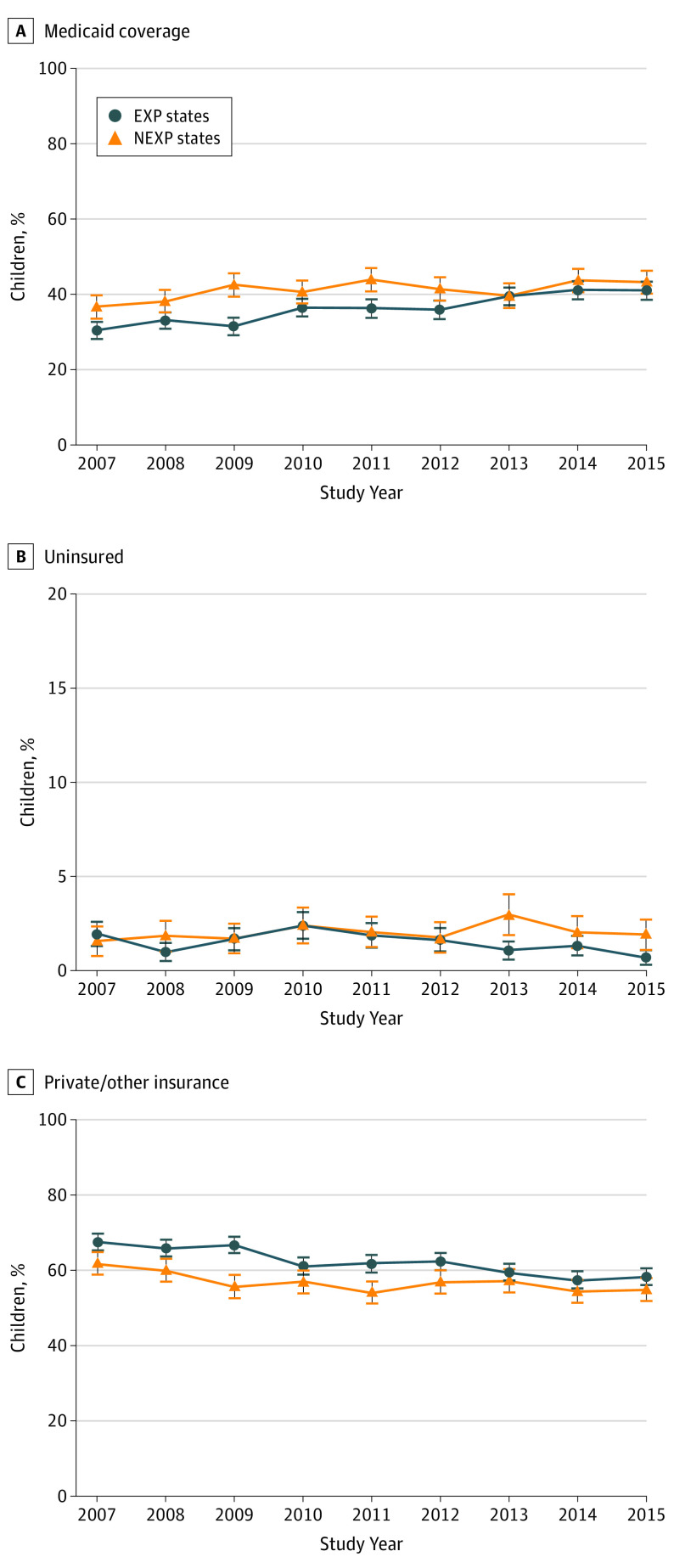

The percentage of children with Medicaid in EXP states rose by 5.0% from 2009 to 2010 with an upward trend, whereas a relatively flat trend was found in NEXP states after 2009 (Figure, A). Net positive increases in Medicaid were observed overall across all subgroups in EXP states (PP range, 2.0%-16.6%) and most subgroups in NEXP states (PP range, −3.2% to 9.5%) after 2010 (Table 2).

Figure. Trends in Insurance Coverage.

Data include children with cancer in early Medicaid expansion (EXP) and nonexpansion (NEXP) states. Error bars denote 95% CIs.

Table 2. Changes in the Percentage of Children With Medicaid Associated With 2010 Medicaid Expansiona.

| Characteristic | EXP states, % | Percentage point changeb |

NEXP states, % | Percentage point changeb |

DID estimate (95% CI) | P value | DDD P value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007- 2009 |

2011- 2015 |

2007- 2009 |

2011- 2015 |

Unadjusted | Adjustedc | |||||

| Overall | 31.8 | 39.3 | 7.5 (23.6) | 39.3 | 42.1 | 2.8 (7.1) | 4.59 (1.77 to 7.42) | 5.25 (2.61 to 7.89) | <.001 | NA |

| Age, y | ||||||||||

| <1 | 35.7 | 43.8 | 8.1 (22.7) | 39.0 | 48.5 | 9.5 (24.4) | −1.33 (−10.34 to 7.67) | 0.15 (−8.02 to 8.32) | .97 | .56 |

| 1-4 | 33.5 | 40.6 | 7.1 (21.2) | 43.9 | 44.7 | 0.8 (1.8) | 6.36 (1.56 to 11.17) | 6.95 (2.6 to 11.31) | .002 | |

| 5-9 | 32.4 | 40.0 | 7.6 (23.5) | 39.6 | 42.6 | 3.0 (7.6) | 4.67 (−0.91 to 10.26) | 5.18 (0.05 to 10.31) | .048 | |

| 10-14 | 27.9 | 35.8 | 7.9 (28.3) | 33.2 | 36.5 | 3.3 (9.9) | 4.58 (−0.53 to 9.69) | 5.23 (0.43 to 10.02) | .033 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 12.9 | 20.6 | 7.7 (59.7) | 29.9 | 31.9 | 2.0 (6.7) | 5.75 (2.38 to 9.12) | 5.38 (2.12 to 8.63) | .001 | .53 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 32.1 | 42.6 | 10.5 (32.7) | 58.2 | 58.4 | 0.2 (0.3) | 10.30 (1.87 to 18.72) | 9.68 (1.22 to 18.14) | .03 | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 22.3 | 24.3 | 2.0 (9.0) | 46.5 | 48.4 | 1.9 (4.1) | 0.11 (−10.39 to 10.61) | −0.19 (−9.81 to 9.42) | .97 | |

| Hispanic | 53.1 | 61.2 | 8.1 (15.3) | 60.5 | 64.6 | 4.1 (6.8) | 4.02 (−3.15 to 11.19) | 4.14 (−3.06 to 11.33) | .26 | |

| Male | 30.6 | 40.5 | 9.9 (32.4) | 41.6 | 42.6 | 1 (2.4) | 8.91 (5.04 to 12.77) | 9.67 (6.05 to 13.28) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Female | 33.3 | 37.9 | 4.6 (13.8) | 36.5 | 41.6 | 5.1 (14.0) | −0.49 (−4.62 to 3.64) | 0.12 (−3.73 to 3.98) | .95 | |

| Nonmetropolitan area | 33.7 | 50.3 | 16.6 (49.3) | 44.7 | 47.1 | 2.4 (5.4) | 14.30 (1.12 to 27.48) | 13.47 (0.89 to 26.06) | .04 | .24 |

| Metropolitan area | 31.8 | 39.1 | 7.3 (23.0) | 37.5 | 40.4 | 2.9 (7.7) | 4.42 (1.36 to 7.47) | 5.02 (2.20 to 7.85) | <.001 | |

| County educational level | ||||||||||

| High | 14.1 | 22.3 | 8.2 (58.2) | 30.2 | 36.3 | 6.1 (20.2) | 2.09 (−2.9 to 7.08) | 1.90 (−2.93 to 6.73) | .44 | .11 |

| Middle to high | 20.6 | 26.6 | 6.0 (29.1) | 38.3 | 41.6 | 3.3 (8.6) | 2.68 (−2.68 to 8.03) | 4.02 (−1.00 to 9.04) | .12 | |

| Middle to low | 31.0 | 38.1 | 7.1 (22.9) | 42.3 | 44.1 | 1.8 (4.3) | 5.32 (−0.31 to 10.95) | 5.94 (0.74 to 11.14) | .03 | |

| Low | 47.3 | 55.9 | 8.6 (18.2) | 55.0 | 51.8 | −3.2 (−5.8) | 11.71 (4.97 to 18.44) | 11.95 (5.61 to 18.3) | <.001 | |

| County poverty level | ||||||||||

| Low | 15.3 | 20.7 | 5.4 (35.3) | 28.4 | 35.3 | 6.9 (24.3) | −1.52 (−7.21 to 4.17) | −0.96 (−6.41 to 4.48) | .73 | .04 |

| Middle to low | 28.9 | 37.5 | 8.6 (29.8) | 29.4 | 35.6 | 6.2 (21.1) | 2.39 (−3.09 to 7.86) | 4.38 (−0.84 to 9.59) | .10 | |

| Middle to high | 34.1 | 42.4 | 8.3 (24.3) | 42.6 | 41.6 | −1.0 (−2.3) | 9.27 (3.02 to 15.51) | 10.18 (4.22 to 16.14) | .001 | |

| High | 48.6 | 56.9 | 8.3 (17.1) | 49.8 | 51.4 | 1.6 (3.2) | 6.73 (1.49 to 11.96) | 6.13 (1.10 to 11.15) | .02 | |

Abbreviations: DDD, difference-in-difference-in-differences; DID, difference in differences; EXP, early expansion; NA, not applicable; NEXP, non–early expansion.

Estimates are based on multiple imputation with the exception of the complete case analysis results. Note that the following analyses did not meet the parallel trends assumption and should be interpreted with caution: Medicaid non-Hispanic white and Medicaid midde to low county poverty level.

Percentage point change is the absolute difference between the 2011 to 2015 and 2007 to 2009 percentages. Data in parentheses are expressed as the percentage point change divided by the 2007 to 2009 percentage.

Estimates are based on models adjusted for age, race, sex, residence, county educational level, and county poverty level, except the variable used to define strata in stratified analyses.

There was a 7.5% increase in EXP states (31.8% before to 39.3% after expansion) and a 2.8% increase in NEXP states (39.3% before to 42.1% after expansion) in Medicaid coverage. In DID analyses, relative to children with cancer from NEXP states, those in EXP states had a 5.25% increase (95% CI, 2.61%-7.89%; P < .001) in Medicaid. In stratified DID analyses, most subpopulations had larger Medicaid increases in EXP vs NEXP states (Table 2 and eFigure 1A in the Supplement). Medicaid coverage increased to a larger degree in boys than girls (adjusted DID estimates, 9.67% [95% CI, 6.05%-13.28%] vs 0.12% [95% CI, −3.73% to 3.98%]; P < .001 for interaction) and in residents of counties with middle to high (adjusted DID estimates, 10.18% [95% CI, 4.22%-16.14%]; P = .005 for interaction) and high (6.13% [95% CI, 1.10%-11.15%]; P = .05 for interaction) poverty levels than in those of low-poverty counties (−0.96% [95% CI, −6.41% to 4.48%]) in EXP vs NEXP states (Table 2 and eFigure 2A and B in the Supplement).

Uninsured Children

In EXP states, the percentage of uninsured children peaked in 2010, followed by a steady decrease thereafter. In contrast, the percentage of uninsured children peaked in 2013 in NEXP states. At the end of the study period, the rate of uninsured children was higher in NEXP than in EXP states (Figure, B). Net decreases occurred in 13 of 20 subgroups and no change occurred in 4 of 20 subgroups in EXP states (PP range, −2.1% to 0.3%), and net decreases occurred in 2 of 20 subgroups in NEXP states (PP range, −0.5% to 1.7%) (Table 3). Overall, there was a −0.2% decrease (from 1.5% before to 1.3% after expansion) in the percentage of uninsured children in EXP states and a 0.5% increase (from 1.7% before to 2.2% after expansion) in NEXP states. Relative to children with cancer in NEXP states, those in EXP states had a −0.73% decrease (95% CI, −1.49% to 0.03%; P = .06) in the percentage of uninsured children (Table 3 and eFigure 1B in the Supplement). In stratified DID analyses, there were decreases in the percentage of uninsured children in EXP vs NEXP states for most subgroups, with the largest expansion-associated decreases in children ages 1 to 4 years (−1.34%; 95% CI, −2.52% to −0.16%; P = .03) (Table 3 and eFigure 1B in the Supplement), although differences were not statistically significant between any subpopulations in the DDD analysis (P > .22) (Table 3).

Table 3. Changes in the Percentage of Children Without Insurance Associated With 2010 Medicaid Expansiona.

| Characteristic | EXP states, % | Percentage point changeb | NEXP states, % | Percentage point changeb |

DID estimate (95% CI) | P value | DDD P value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007- 2009 |

2011- 2015 |

2007- 2009 |

2011- 2015 |

Unadjusted | Adjustedc | |||||

| Overall | 1.5 | 1.3 | −0.2 (−13.3) | 1.7 | 2.2 | 0.5 (29.4) | −0.76 (−1.52 to −0.01) | −0.73 (−1.49 to 0.03) | .06 | NA |

| Age, y | ||||||||||

| <1 | 1.7 | 0.9 | −0.8 (−47.1) | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.6 (46.2) | −1.48 (−3.69 to 0.73) | −1.23 (−3.35 to 0.90) | .26 | .62 |

| 1-4 | 1.3 | 1.0 | −0.3 (−23.1) | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.3 (118.2) | −1.46 (−2.63 to −0.29) | −1.34 (−2.52 to −0.16) | .03 | |

| 5-9 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 0.4 (18.2) | −0.40 (−1.97 to 1.17) | −0.45 (−1.91 to 1.01) | .55 | |

| 10-14 | 2.1 | 1.7 | −0.4 (−19.0) | 2.2 | 1.7 | −0.5 (−22.7) | −0.02 (−1.53 to 1.50) | −0.09 (−1.58 to 1.40) | .90 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.3 (33.3) | 1.4 | 1.8 | 0.4 (28.6) | −0.10 (−1.01 to 0.80) | −0.07 (−0.98 to 0.84) | .87 | .77 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2.2 | 2.2 | 0 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 0.5 (25.0) | −0.45 (−3.00 to 2.10) | −0.62 (−3.18 to 1.94) | .64 | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 1.4 | 0.9 | −0.5 (−35.7) | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.7 (116.7) | −1.22 (−3.31 to 0.87) | −1.29 (−3.54 to 0.96) | .26 | |

| Hispanic | 2.1 | 1.3 | −0.8 (−38.1) | 3.8 | 4.3 | 0.5 (13.2) | −1.38 (−4.16 to 1.39) | −1.22 (−3.43 to 0.99) | .28 | |

| Male | 1.5 | 1.4 | −0.1 (−6.7) | 1.7 | 2.1 | 0.4 (23.5) | −0.48 (−1.51 to 0.55) | −0.48 (−1.49 to 0.53) | .35 | .49 |

| Female | 1.5 | 1.1 | −0.4 (−26.7) | 1.7 | 2.3 | 0.6 (35.3) | −1.08 (−2.20 to 0.03) | −1.01 (−2.14 to 0.12) | .08 | |

| Nonmetropolitan area | 4.0 | 1.9 | −2.1 (−52.5) | 2.5 | 4.0 | 1.5 (60.0) | −3.60 (−8.33 to 1.13) | −3.37 (−7.91 to 1.17) | .15 | .22 |

| Metropolitan area | 1.5 | 1.2 | −0.3 (−20.0) | 1.5 | 1.7 | 0.2 (13.3) | −0.48 (−1.25 to 0.30) | −0.47 (−1.24 to 0.30) | .23 | |

| County educational level | ||||||||||

| High | 1.4 | 0.9 | −0.5 (−35.7) | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.9 (81.8) | −1.38 (−2.72 to −0.04) | −1.50 (−2.83 to −0.17) | .03 | .42 |

| Middle to high | 1.9 | 0.9 | −1.0 (−52.6) | 1.8 | 2.1 | 0.3 (16.7) | −1.38 (−2.89 to 0.12) | −1.31 (−2.79 to 0.16) | .08 | |

| Middle to low | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.1 (5.3) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.07 (−1.53 to 1.68) | 0.17 (−1.41 to 1.75) | .83 | |

| Low | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 0.8 (34.8) | −0.73 (−2.77 to 1.32) | −0.67 (−2.37 to 1.03) | .44 | |

| County poverty level | ||||||||||

| Low | 1.6 | 1.0 | −0.6 (−37.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0 | −0.69 (−2.03 to 0.64) | −0.80 (−2.18 to 0.57) | .25 | .35 |

| Middle to low | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.7 (188.9) | −1.77 (−3.21 to −0.34) | −1.55 (−3.03 to −0.08) | .04 | |

| Middle to high | 2.4 | 1.6 | −0.8 (−33.3) | 2.0 | 2.5 | 0.5 (25.0) | −1.30 (−3.14 to 0.54) | −1.18 (−3.01 to 0.65) | .21 | |

| High | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.1 (9.1) | 2.5 | 2.3 | −0.2 (−8.0) | 0.28 (−1.17 to 1.72) | 0.25 (−1.12 to 1.62) | .72 | |

Abbreviations: DDD, difference-in-difference-in-differences; DID, difference in differences; EXP, early expansion; NA, not applicable; NEXP, non–early expansion.

Estimates are based on multiple imputation with the exception of the complete case analysis results. Note that the following analyses did not meet the parallel trends assumption and should be interpreted with caution: Medicaid non-Hispanic white and Medicaid midde to low county poverty level.

Percentage point change is the absolute difference between the 2011 to 2015 and 2007 to 2009 percentages. Data in parentheses are expressed as the percentage point change divided by the 2007 to 2009 percentage.

Estimates are based on models adjusted for age, race, sex, residence, county educational level, and county poverty level, except the variable used to define strata in stratified analyses.

Privately/Other Insured Children

The percentage of children with private or other insurance declined during the study period in EXP and NEXP states, with the largest decline in EXP states in 2010 (Figure, C). Net negative decreases occurred in all subgroups in EXP states (PP range, −14.6% to −1.5%) and 18 of 20 subgroups in NEXP states (PP range, −10.1% to 2.4%) (Table 4). There was a −7.2% reduction (66.6% before to 59.4% after expansion) in EXP states and a −3.3% reduction (59.0% before to 55.7% after expansion) in NEXP states. In EXP relative to NEXP states, there was an overall net decrease in private or other insurance of −4.52% (95% CI, −7.16% to −1.88%; P < .001), with decreases in most subgroups (Table 4 and eFigure 1C in the Supplement). Relative to children from counties with low poverty (1.76%; 95% CI, −3.76% to 7.28%), the expansion-associated decrease was greater for those from counties with middle to high (−9.00%; 95% CI, −14.98 to −3.02) and high (−6.38%; 95% CI, −11.36 to −1.40) poverty (P = .04 for interaction).

Table 4. Changes in the Percentage of Children With Private or Other Insurance Associated With 2010 Medicaid Expansiona.

| Characteristic | EXP states, % | Percentage point changeb |

NEXP states, % | Percentage point changeb |

DID estimate (95% CI) | P value | DDD P value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007- 2009 |

2011- 2015 |

2007- 2009 |

2011- 2015 |

Unadjusted | Adjustedc | |||||

| Overall | 66.6 | 59.4 | −7.2 (−10.8) | 59.0 | 55.7 | −3.3 (−5.6) | −3.83 (−6.67 to −0.98) | −4.52 (−7.16 to −1.88) | <.001 | NA |

| Age, y | ||||||||||

| <1 | 62.5 | 55.3 | −7.2 (−11.5) | 59.7 | 49.6 | −10.1 (−16.9) | 2.82 (−6.23 to 11.86) | 1.08 (−7.16 to 9.31) | .80 | .56 |

| 1-4 | 65.3 | 58.4 | −6.9 (−10.6) | 55.0 | 53.0 | −2.0 (−3.6) | −4.90 (−9.73 to −0.07) | −5.61 (−10.09 to −1.13) | .01 | |

| 5-9 | 66.5 | 58.8 | −7.7 (−11.6) | 58.2 | 54.9 | −3.3 (−5.7) | −4.28 (−9.90 to 1.35) | −4.73 (−9.96 to 0.51) | .08 | |

| 10-14 | 69.9 | 62.5 | −7.4 (−10.6) | 64.6 | 61.8 | −2.8 (−4.3) | −4.56 (−9.74 to 0.62) | −5.14 (−10.01 to −0.26) | .04 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 86.3 | 78.2 | −8.1 (−9.4) | 68.8 | 66.3 | −2.5 (−3.6) | −5.65 (−9.07 to −2.22) | −5.30 (−8.60 to −2.00) | .002 | .41 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 65.7 | 55.2 | −10.5 (−16.0) | 39.7 | 39.1 | −0.6 (−1.5) | −9.85 (−18.30 to −1.40) | −9.06 (−17.43 to −0.69) | .03 | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 76.3 | 74.8 | −1.5 (−2.0) | 52.9 | 50.3 | −2.6 (−4.9) | 1.11 (−9.43 to 11.65) | 1.48 (−9.00 to 11.97) | .78 | |

| Hispanic | 44.8 | 37.5 | −7.3 (−16.3) | 35.7 | 31.1 | −4.6 (−12.9) | −2.64 (−9.66 to 4.38) | −2.92 (−9.92 to 4.09) | .42 | |

| Male | 67.9 | 58.1 | −9.8 (−14.4) | 56.7 | 55.4 | −1.3 (−2.3) | −8.43 (−12.32 to −4.53) | −9.18 (−12.81 to −5.56) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Female | 65.2 | 61.0 | −4.2 (−6.4) | 61.8 | 56.0 | −5.8 (−9.4) | 1.58 (−2.59 to 5.74) | 0.88 (−3.01 to 4.78) | .66 | |

| Nonmetropolitan area | 62.4 | 47.8 | −14.6 (−23.4) | 52.8 | 48.9 | −3.9 (−7.4) | −10.70 (−24.05 to 2.64) | −10.10 (−22.82 to 2.62) | .12 | .47 |

| Metropolitan area | 66.7 | 59.7 | −7.0 (−10.5) | 60.9 | 57.9 | −3.0 (−4.9) | −3.94 (−7.02 to −0.86) | −4.55 (−7.40 to −1.70) | .002 | |

| County educational level | ||||||||||

| High | 84.5 | 76.8 | −7.7 (−9.1) | 68.7 | 61.7 | −7.0 (−10.2) | −0.71 (−5.79 to 4.36) | −0.40 (−5.25 to 4.44) | .87 | .06 |

| Middle to high | 77.5 | 72.5 | −5.0 (−6.5) | 60.0 | 56.3 | −3.7 (−6.2) | −1.29 (−6.72 to 4.13) | −2.71 (−7.79 to 2.37) | .30 | |

| Middle to low | 67.1 | 60.0 | −7.1 (−10.6) | 55.7 | 53.9 | −1.8 (−3.2) | −5.39 (−11.06 to 0.28) | −6.12 (−11.45 to −0.78) | .03 | |

| Low | 51.5 | 42.9 | −8.6 (−16.7) | 42.7 | 45.1 | 2.4 (5.6) | −10.98 (−17.68 to −4.28) | −11.29 (−17.83 to −4.74) | .001 | |

| County poverty level | ||||||||||

| Low | 83.1 | 78.4 | −4.7 (−5.7) | 70.6 | 63.7 | −6.9 (−9.8) | 2.21 (−3.55 to 7.98) | 1.76 (−3.76 to 7.28) | .53 | .04 |

| Middle to low | 69.7 | 61.1 | −8.6 (−12.3) | 69.7 | 61.7 | −8.0 (−11.5) | −0.61 (−6.15 to 4.92) | −2.82 (−8.09 to 2.45) | .29 | |

| Middle to high | 63.5 | 55.9 | −7.6 (−12.0) | 55.5 | 55.9 | 0.4 (0.7) | −7.97 (−14.26 to −1.67) | −9.00 (−14.98 to −3.02) | .003 | |

| High | 50.3 | 41.9 | −8.4 (−16.7) | 47.7 | 46.4 | −1.3 (−2.7) | −7.01 (−12.23 to −1.78) | −6.38 (−11.36 to −1.40) | .01 | |

Abbreviations: DDD, difference-in-difference-in-differences; DID, difference in differences; EXP, early expansion; NA, not applicable; NEXP, non–early expansion.

Estimates are based on multiple imputation with the exception of the complete case analysis results. Note that the following analyses did not meet the parallel trends assumption and should be interpreted with caution: Medicaid non-Hispanic white and Medicaid midde to low county poverty level.

Percentage point change is the absolute difference between the 2011 to 2015 and 2007 to 2009 percentages. Data in parentheses are expressed as the percentage point change divided by the 2007 to 2009 percentage.

Estimates are based on models adjusted for age, race, sex, residence, county educational level, and county poverty level, except the variable used to define strata in stratified analyses.

Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility in Children

The mean eligibility levels for Medicaid and CHIP were 269% of the federal poverty limit in 2006, 273% in 2009, and 287% in 2014 in EXP states; and in NEXP states, these levels were 216% in 2006, 233% in 2009, and 256% in 2014. Among NEXP states, those expanding by 2014 saw the largest increases (mean, 213% to 273% of the federal poverty limit from 2006 to 2014 vs 218% to 243% of the federal poverty limit in those not expanding by 2014) (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Supplemental Analyses

In the 2014 expansion analysis, a nonsignificant increase in Medicaid (2.16%; 95% CI, −2.00% to 6.31%; P = .31) and a nonsignificant decrease in uninsured (−0.74%; 95% CI, −2.07% to 0.58%; P = .27) and private or other insurance (−1.41%; 95% CI, −5.61% to 2.78%; P = .51) was observed in EXP vs NEXP states. Variation in expansion-associated changes in Medicaid and uninsured proportions between subgroups occurred in expected directions, although not significant (P ≥ .14) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Examining percentages of uninsured children by expansion status revealed that states that expanded in 2010 and 2014 had similar percentages of uninsured (1.0%), but states not expanding had higher percentages of uninsured (2.8%) (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Results of other sensitivity analyses were similar to those of the main results (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Overall, our results indicate a clear increase in Medicaid coverage and decreases in private and other insurance among children with cancer after the 2010 state Medicaid expansions, particularly among boys and among children residing in counties with higher poverty levels. We observed an expansion-associated decrease in the percentage of uninsured children overall, with significant reductions among children aged 1 to 4 years, consistent with our findings of the largest Medicaid increases in this age group.

A major contributing factor of Medicaid coverage increases alongside private insurance reductions is likely the 2008-2009 recession. Parents and guardians may have become unemployed and lost employer-sponsored coverage, which is consistent with the increase in uninsured children in NEXP states. Another likely contributing factor is that families in EXP states switched from private to public coverage due to its affordability, a phenomenon termed crowd out, in agreement with a recent study using American Community Survey data26 and with the observation that greater decreases in private insurance occurred relative to the decreases in uninsured individuals in EXP states. Parents and guardians may also have switched their child’s coverage to Medicaid or CHIP at cancer diagnosis if the public option provided more comprehensive coverage, because pre-2014 private insurance plans were not required to cover essential health benefits.27 Larger decreases in private insurance in 2014 EXP states have similarly been reported in adults, although results are mixed.28,29,30,31,32,33,34

Expansion-associated decreases in the percentage of uninsured children may have occurred for at least 4 reasons. First, eligible but previously uninsured children may have enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP after their parents or guardians gained Medicaid coverage (known as welcome-mat effects).14,35,36 Second, applicants are assessed for Medicaid and CHIP eligibility during ACA enrollment, and eligible children may have enrolled in state marketplaces with enrollment authority.37 The percentage of eligible children with Medicaid or CHIP increased from 81.7% to 93.7% from 2008 to 2016,35 consistent with this explanation.

A third reason relates to increases in state-based Medicaid and CHIP coverage limits for children from a median of 235% to 255% of the federal poverty limit from 2009 to 2014 (eTable 1 in the Supplement).35,36,38 However, eligibility limits increased similarly in EXP and NEXP states and should not affect our results. However, higher absolute CHIP eligibility limits play a role. Stratifying NEXP states by their 2014 expansion status revealed that most eligibility limit increases were in 2014 expansion states after expansion, resulting in identical uninsured rates for EXP and 2014 expansion states but a rate of uninsured 2.8 times higher in the states that never expanded Medicaid (by 2015) (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). In other words, when assessing the overall (early and 2014) Medicaid expansion, including CHIP eligibility increases, we found that the uninsured rate among children with cancer is greatly reduced in the presence of expansion. Those who remain uninsured are likely those in families earning incomes just above CHIP eligibility, which is low enough to possibly make private insurance unaffordable for those without employer coverage options. Other policy changes, such as lower CHIP premiums for some income groups, may have played a role.

Another reason is ACA-associated outreach, particularly in EXP states, including advertisement of insurance affordability and education regarding the benefits of continuous insurance. Outreach may also explain the broadly increased Medicaid and CHIP coverage and the particular increase among children of lower socioeconomic status.14

Results from prior studies have been mixed regarding the effects of Medicaid expansion and health reform on decreasing numbers of uninsured children. One study examining the 2014 expansion35 found similar decreases in the percentage of uninsured in Medicaid EXP and NEXP states from 2013 to 2016 (EXP states, 5.9% to 3.2%; NEXP states, 8.6% to 5.9%), although the uninsured rate was 1.8 times higher in NEXP states. Another study26 found an expansion-associated decrease of 3% in the percentage uninsured, but as in the present study, there was also a reduction in private insurance. A 2006 Massachusetts health care reform study found that the uninsured rate was cut in half,12 although the Massachusetts reform notably included multiple components, including raising the Medicaid eligibility threshold for children.

Because a primary component of Medicaid eligibility is income,36,38,39 variations in Medicaid uptake by county poverty and educational level are unsurprising. As expected, the largest relative gains in Medicaid coverage were observed in children living in counties with middle to high and high poverty levels, although changes in the percentage of uninsured children by poverty level were less evident. There was a similar nonsignificant pattern by county educational level, with greater changes in Medicaid and private coverage in counties with lower levels of education.

We observed the largest Medicaid increases and uninsured decreases among children aged 1 to 4 years. Children in this age group and their parents or guardians are more likely to be enrolled in Medicaid than older children,40 which may be related to their higher Medicaid eligibility limits. Thus, changes to policies affecting Medicaid are expected to have larger effects on younger children. The relatively larger expansion-associated changes in insurance coverage in children aged 1 to 4 years vs infants may be associated with Medicaid eligibility during pregnancy, because many pregnant women were eligible for Medicaid before expansion, and the policy would be expected to have less effect.38

We observed a greater increase in Medicaid coverage and a larger decrease in private and other insurance associated with early expansion in boys than girls, which may be explained by more frequent office visits in boys (262 vs 197 visits per 100 persons per year).41 Parents and guardians of boys may switch from private or other coverage to Medicaid at higher rates before and unrelated to a cancer diagnosis, perhaps owing to cost concerns. However, the 2014 expansion data did not show a similar pattern (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

The question arises whether net benefits are associated with expansion of Medicaid to children with cancer if much of the increase in Medicaid among children is due to shifts from private insurance. Although Medicaid likely reduces health care costs and financial hardship for families, if parents have difficulty finding a clinician who takes Medicaid, diagnosis delays may result. One study suggests that children with Medicaid are diagnosed at later stages compared with children with private insurance.42 Clinicians have historically accepted new Medicaid patients at lower rates than new privately insured children,43 although rates of accepting new Medicaid patients have increased with increased Medicaid reimbursements under the ACA.44 However, children with Medicaid vs private insurance are as successful in obtaining care, with 96% and 98%, respectively, reporting a usual source of care in 2017.45 Hence, at least for children, it appears that access to care is similar for those with Medicaid and private insurance.

Strengths and Limitations

Study strengths include the use of a national population-based database, a quasi-experimental design, and several years of follow-up for examination of changes in insurance coverage. In addition, to our knowledge, no prior studies have examined ACA-associated changes in insurance coverage in children with cancer, a vulnerable population with high medical costs.46 Our study also has limitations. First, county-level income and educational variables may not fully capture heterogeneity of individual-level insurance coverage. Second, retroactive Medicaid enrollment after a cancer diagnosis as well as insurance misclassification may obscure results.47,48,49,50 However, any misclassification would likely be unrelated to expansion and thus biased toward the null. Third, although we used multiple imputation to address potential bias from missing data, bias could still be present if values are missing not at random (eTable 3 in the Supplement).51 Fourth, the validity of DID analyses relies on an adequate comparison group to avoid parallel trend and common shocks assumption violations.52 Although nearly all analyses met the parallel trends assumption, a concern regarding the common shocks assumption is the effect of the 2008-2009 economic recession on employment and employer-sponsored insurance among parents and guardians of children with cancer. However, changes in unemployment were similar in EXP and NEXP states, suggesting equal effects in both groups (eFigure 4 in the Supplement, based on unemployment data53 from SEER states weighted by state population54). In addition, SEER does not include information about secondary insurance; thus, we are not able to determine the effect on our results of children jointly insured by a private plan and Medicaid.

Conclusions

Medicaid coverage among children with cancer increased in association with Medicaid expansion across most subgroups, particularly children aged 1 to 4 years, boys, and residents of counties with higher levels of poverty. Improving access to affordable health care for children remains an important issue.55,56,57,58,59,60,61 Our results suggest that expanding Medicaid eligibility for children or parents and guardians increases Medicaid coverage among children through a combination of decreases in privately insured and uninsured children. This increase may in turn lead to less financial anxiety among families of children with cancer, earlier cancer diagnoses, and improved prognosis.

eMethods. Sensitivity Analysis Methods, Missing Data, and Multiple Imputation

eFigure 1. Adjusted Difference-in-Differences (DID) Estimates of Percentage Point Change in Insurance Type

eFigure 2. Trends in Medicaid Coverage in Children With Cancer Over Study Period

eFigure 3. Change in Childhood Cancer Insurance Status Over Time by State Medicaid Expansion Status

eFigure 4. The Percentage of Adults Unemployed in EXP and NEXP States During Time Period Surrounding the Recession

eTable 1. Federal Poverty Limit Eligibility Levels for Medicaid/CHIP by Month/Year, Expansion Status, and Period

eTable 2. Results of Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 3. Characteristics of Study Population by Missing Data on Insurance Status

eReferences.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention United States and Puerto Rico cancer statistics, 1999-2014 incidence archive request. Published April 2017. Accessed February 10, 2020. https://wonder.cdc.gov/cancer-v2014.html

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention United States and Puerto Rico cancer statistics, 1999-2014 mortality request. Published April 2017. Accessed February 10, 2020. https://wonder.cdc.gov/cancermort-v2016.html

- 3.Dang-Tan T, Franco EL. Diagnosis delays in childhood cancer: a review. Cancer. 2007;110(4):703-713. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta S, Wilejto M, Pole JD, Guttmann A, Sung L. Low socioeconomic status is associated with worse survival in children with cancer: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89482. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett JC, Vornovitsky MS. Current Population Reports, P60-257(RV), Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2015 US Government Printing Office; September 2016. Accessed February 10, 2020. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p60-257.pdf

- 6.Lee JM, Wang X, Ojha RP, Johnson KJ. The effect of health insurance on childhood cancer survival in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123(24):4878-4885. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. States getting a jump start on health reform’s Medicaid expansion. Published April 2, 2012. Accessed January 5, 2019. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/states-getting-a-jump-start-on-health/

- 8.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. Updated January 10, 2020. Accessed January 5, 2019. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/

- 9.Berchick ER, Hood E, Barnett JC. Current Population Reports, P60-264, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2017 US Government Printing Office; September 2018. Accessed January 5, 2019. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-264.pdf

- 10.DeVoe JE, Tillotson CJ, Angier H, Wallace LS. Predictors of children’s health insurance coverage discontinuity in 1998 versus 2009: parental coverage continuity plays a major role. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(4):889-896. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1590-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubay L, Kenney G. Expanding public health insurance to parents: effects on children’s coverage under Medicaid. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(5):1283-1301. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenney GM, Long SK, Luque A. Health reform in Massachusetts cut the uninsurance rate among children in half. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(6):1242-1247. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeVoe JE, Marino M, Angier H, et al. Effect of expanding Medicaid for parents on children’s health insurance coverage: lessons from the Oregon experiment. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(1):e143145. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson JL, Moriya AS. Medicaid expansion for adults had measurable “welcome mat” effects on their children. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1643-1651. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkataramani M, Pollack CE, Roberts ET. Spillover effects of adult Medicaid expansions on children’s use of preventive services. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20170953. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsimicalis A, Stevens B, Ungar WJ, et al. A mixed method approach to describe the out-of-pocket expenses incurred by families of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(3):438-445. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsimicalis A, Stevens B, Ungar WJ, Castro A, Greenberg M, Barr R. Shifting priorities for the survival of my child: managing expenses, increasing debt, and tapping into available resources to maintain the financial stability of the family. Cancer Nurs. Published online April 3, 2019. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelletier W, Bona K. Assessment of financial burden as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(S5)(suppl 5):S619-S631. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute. About the SEER program. Accessed May 7, 2018. https://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html

- 20.National Cancer Institute. Insurance Recode (2007). Accessed February 10, 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/variables/seer/insurance-recode/

- 21.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1987. doi: 10.1002/9780470316696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimick JB, Ryan AM. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2401-2402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wing C, Simon K, Bello-Gomez RA. Designing difference in difference studies: best practices for public health policy research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:453-469. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Draper NR, Smith H. Applied Regression Analysis. John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1998. doi: 10.1002/9781118625590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid/CHIP upper income eligibility limits for children, 2000-2019. Accessed May 17, 2019. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaidchip-upper-income-eligibility-limits-for-children/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- 26.Ugwi P, Lyu W, Wehby GL. The effects of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on children’s health coverage. Med Care. 2019;57(2):115-122. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bagley N, Levy H. Essential health benefits and the Affordable Care Act: law and process. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2014;39(2):441-465. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2416325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frean M, Gruber J, Sommers BD. Premium subsidies, the mandate, and Medicaid expansion: coverage effects of the Affordable Care Act. J Health Econ. 2017;53:72-86. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen RA, Martinez ME Health insurance coverage: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January-March 2015. Released August 2015. Accessed April 8, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/insur201508.pdf

- 30.Leung P, Mas A Employment effects of the ACA Medicaid expansions. Issued August 2016. Accessed April 8, 2019. https://www.nber.org/papers/w22540

- 31.Decker SL, Lipton BJ, Sommers BD. Medicaid expansion coverage effects grew in 2015 with continued improvements in coverage quality. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):819-825. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):947-956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1612890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wehby GL, Lyu W. The impact of the ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage through 2015 and coverage disparities by age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):1248-1271. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courtemanche Ch, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. Early impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(1):178-210. doi: 10.1002/pam.21961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haley J, Kenney GM, Wang R, Pan C, Lynch V, Buettgens M Uninsurance and Medicaid/CHIP participation among children and parents: variation in 2016 and recent trends. Published September 2018. Accessed January 7, 2019. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99058/uninsurance_and_medicaidchip_participation_among_children_and_parents_2.pdf

- 36.Heberlein M, Brooks T, Artiga S, Stephens J Getting into gear for 2014: shifting new Medicaid eligibility and enrollment policies into drive. Published November 21, 2013. Accessed January 7, 2019. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/getting-into-gear-for-2014-shifting-new-medicaid-eligibility-and-enrollment-policies-into-drive/

- 37.Hudson JL, Moriya AS. Association between marketplace policy and public coverage among Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program–eligible children and parents. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(9):881-882. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross DC, Jarlenski M, Artiga S, Marks C A foundation for health reform: findings of a 50 state survey of eligibility rules, enrollment and renewal procedures, and cost-sharing practices in Medicaid and CHIP for children and parents during 2009. Published December 2009. Accessed January 7, 2019. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/8028.pdf

- 39.Brooks T, Wagnerman K, Artiga S, Cornachione E Medicaid and CHIP eligibility, enrollment, renewal, and cost sharing policies as of January 2018: findings from a 50-state survey. Published March 21, 2008. Accessed January 7, 2019. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-enrollment-renewal-and-cost-sharing-policies-as-of-january-2018-findings-from-a-50-state-survey/

- 40.Haley J, Wang R, Buettgens M, Kenney GM Health insurance coverage among children ages 3 and younger and their parents in 2016: national and state estimates. Published January 2018. Accessed January 7, 2019. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/96141/medicaid_chip_2001686_0.pdf

- 41.National Center for Health Statistics. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2015 patient record. Published December 17, 2014. Accessed January 11, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/2015_NAMCS_PRF_Sample_Card.pdf

- 42.Wang X, Ojha RP, Johnson KJ. Abstract 4465: the effect of insurance status on childhood and adolescent cancer survival using data from the National Cancer Database [published online July 1, 2019]. Cancer Res. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2019-4465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.AAP Department of Practice Pediatrician participation in Medicaid and CHIP: national and state reports. Published September 2012. Accessed September 10, 2019. https://www.aap.org/en-us/professional-resources/Research/pediatrician-surveys/Pages/Pediatrician-Participation-in-Medicaid-and-CHIP-National-and-State-Reports.aspx

- 44.Tang SS, Hudak ML, Cooley DM, Shenkin BN, Racine AD. Increased Medicaid payment and participation by office-based primary care pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20172570. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rudowitz R, Garfield R, Hinton E 10 Things to know about Medicaid: setting the facts straight. Updated March 2019. Accessed September 10, 2019. http://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-10-Things-to-Know-about-Medicaid-Setting-the-Facts-Straight

- 46.Price RA, Stranges E, Elixhauser A Statistical brief 132: pediatric cancer hospitalizations, 2009. Published May 2012. Accessed September 24, 2019. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb132.pdf

- 47.Sherman RL, Williamson L, Andrews P, Kahn A. Primary payer at DX: issues with collection and assessment of data quality. J Registry Manag. 2016;43(2):99-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stuber J, Bradley E. Barriers to Medicaid enrollment: who is at risk? Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):292-298. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2002.006254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradley CJ, Gardiner J, Given CW, Roberts C. Cancer, Medicaid enrollment, and survival disparities. Cancer. 2005;103(8):1712-1718. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenberg AR, Kroon L, Chen L, Li CI, Jones B. Insurance status and risk of cancer mortality among adolescents and young adults. Cancer. 2015;121(8):1279-1286. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryan AM, Burgess JF Jr, Dimick JB. Why we should not be indifferent to specification choices for difference-in-differences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1211-1235. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor. 76.9 percent of Hispanic men employed, January 2018. The Economics Daily. Published February 7, 2018. Accessed October 31, 2018. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2018/76-point-9-percent-of-hispanic-men-employed-january-2018.htm

- 54.US Census Bureau. Decennial Census Tables: 2010. Accessed February 10, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/data/tables.2010.html

- 55.Blendon RJ, Benson JM. Public opinion about the future of the Affordable Care Act. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):e12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1710032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lambrew JM. Lessons from the latest ACA battle. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2107-2109. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1712948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gostin LO. Texas v United States: the Affordable Care Act is constitutional and will remain so. JAMA. 2019;321(4):332-333. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butler SM. Will state waivers save, reform, or sabotage Obamacare? JAMA. 2019;321(5):441-442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu JM, Chhabra M, Grande D. Concise research report: the future of Medicaid: state legislator views on policy waivers. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):999-1001. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4432-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.American Medical Association. Summary of CMS’ new guidance to states on Medicaid work requirements. Published January 12, 2018. Accessed January 7, 2019. https://docisolation.prod.fire.glass/?guid=783cbf41-2e32-4837-b12b-bf7e790b429f

- 61.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Understanding the intersection of Medicaid and work: what does the data say? Accessed February 10, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-intersection-of-medicaid-and-work-what-does-the-data-say/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Sensitivity Analysis Methods, Missing Data, and Multiple Imputation

eFigure 1. Adjusted Difference-in-Differences (DID) Estimates of Percentage Point Change in Insurance Type

eFigure 2. Trends in Medicaid Coverage in Children With Cancer Over Study Period

eFigure 3. Change in Childhood Cancer Insurance Status Over Time by State Medicaid Expansion Status

eFigure 4. The Percentage of Adults Unemployed in EXP and NEXP States During Time Period Surrounding the Recession

eTable 1. Federal Poverty Limit Eligibility Levels for Medicaid/CHIP by Month/Year, Expansion Status, and Period

eTable 2. Results of Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 3. Characteristics of Study Population by Missing Data on Insurance Status

eReferences.