Abstract

Hemoglobin functions as a tetrameric oxygen transport protein, with each subunit containing a heme cofactor. Its denaturation, either in vivo or in vitro, involves autoxidation to methemoglobin, followed by cofactor loss and globin unfolding. We have proposed a global disassembly scheme for human methemoglobin, linking hemin (ferric protoporphyrin IX) disassociation and apoprotein unfolding pathways. The model is based on the evaluation of circular dichroism and visible absorbance measurements of guanidine-hydrochloride-induced disassembly of methemoglobin and previous measurements of apohemoglobin unfolding. The populations of holointermediates and equilibrium disassembly parameters were estimated quantitatively for adult and fetal hemoglobins. The key stages are characterized by hexacoordinated hemichrome intermediates, which are important for preventing hemin disassociation from partially unfolded, molten globular species during early disassembly and late-stage assembly events. Both unfolding experiments and independent small angle x-ray scattering measurements demonstrate that heme disassociation leads to the loss of tetrameric structural integrity. Our model predicts that after autoxidation, dimeric and monomeric hemichrome intermediates occur along the disassembly pathway inside red cells, where the hemoglobin concentration is very high. This prediction suggests why misassembled hemoglobins often get trapped as hemichromes that accumulate into insoluble Heinz bodies in the red cells of patients with unstable hemoglobinopathies. These Heinz bodies become deposited on the cell membranes and can lead to hemolysis. Alternatively, when acellular hemoglobin is diluted into blood plasma after red cell lysis, the disassembly pathway appears to be dominated by early hemin disassociation events, which leads to the generation of higher fractions of unfolded apo subunits and free hemin, which are known to damage the integrity of blood vessel walls. Thus, our model provides explanations of the pathophysiology of hemoglobinopathies and other disease states associated with unstable globins and red cell lysis and also insights into the factors governing hemoglobin assembly during erythropoiesis.

Significance

Our global analysis of spectral data for hemoglobin unfolding led to both the characterization of “hidden” hemichrome intermediates and the proposal of a quantitative model for human hemoglobin disassembly and assembly. The importance of this mechanism is severalfold. First, the hemoglobin system serves as a general biological model for understanding the role of oligomerization and cofactor binding in facilitating protein folding and assembly. Second, the fitted parameters provide 1) estimates of hemin affinity for apoprotein states, 2) quantitative interpretations of the pathophysiology of hemoglobinopathies and other diseases associated with unstable globins and red cell lysis, 3) insights into the factors governing hemoglobin assembly during erythropoiesis, and 4) a framework for designing targeted hemoglobinopathy therapeutics.

Introduction

An interwoven relationship between protein function, structure, and oligomerization occurs during hemoglobin assembly through stepwise heme binding that guides the formation of secondary, tertiary, and quaternary protein structures. We depend on erythrocyte-encapsulated hemoglobin (Hb) to transport oxygen in our cardiovascular system (1). Hb regulates cooperative binding of oxygen to each of its ferrous heme iron atoms via its quaternary conformations.

Functional adult human hemoglobin A (HbA) consists of α and β globin subunits interacting at both the α1β1 dimer and α1β2 tetramer interfaces. Each globin subunit has seven or eight α-helical segments labeled A to H and is folded with a heme molecule sandwiched within a cavity between the E and F helices (Fig. 1; (2,3)). The heme iron is axially coordinated to the Nε2 atom of the proximal histidine at the eighth position on the F helix. In the reduced state, this pentacoordinate iron can bind oxygen (O2), carbon monoxide (CO), or nitric oxide (NO) at the sixth coordination position on the distal side of the porphyrin ring (4). We describe free heme or hemin in this study as the cofactor freely available to bind to apoHb subunits. Autoxidation of ferrous heme in oxyHb leads to aquometHb, with H2O bound to Fe(III) protoporphyrin IX (hemin). This metHb form has ≥10,000-fold higher rates of heme disassociation than the corresponding reduced Hb complexes (5, 6, 7). Thus, the first step in disassembly of hemoglobins in vivo most likely involves autoxidation to the metHb form, which is then followed by hemin dissociation and protein unfolding. Free heme itself is unstable in the presence of oxygen and autoxidizes in milliseconds, even when present in membranes or nonspecifically bound to proteins (4,8,9). Therefore, during assembly, it is probably the oxidized form of heme that binds to nascent apopolypeptide chains before reduction occurs. As a result, in our study, we focused on the mechanisms and intermediates that occur during metHb disassembly.

Figure 1.

Structure of metHbA (PDB: 3P5Q) showing the active sites of α and β subunits at the α1β2 interface. Each Fe(III) atom (dark orange) is coordinated to both the proximal histidine at the F8 helical position and a weakly bound water molecule at the distal position. The water molecule (red O atom, white H atoms) is stabilized by a hydrogen bond to the distal histidine at the E7 helical position. Loss of hemin (green) leads to partial unfolding of the heme pocket region, leading to disruption of the α1β2 interface but not the more hydrophobic and stronger α1β1 interface (10). To see this figure in color, go online.

Building on our earlier work (10), we propose the global model in Fig. 2 for HbA disassembly and assembly that involves reversible hemin and subunit disassociations at various unfolding and quaternary stages. The concept that multiple assembly and disassembly pathways can occur for protein complexes formed by coupling between two protein subunits or between a protein subunit and a cofactor has been explored for other protein systems, but not for hemoglobins (11, 12, 13, 14). HbA disassembly is characterized by both types of couplings, and our model predicts that the exact pathway will differ markedly between intracellular red cell and acellular blood plasma environments as a result of marked differences in total protein (and heme) concentrations. To examine the validity of this model, we measured guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl)-induced disassembly of heme-bound holoHb over a wide range of protein concentrations. GdnHCl was chosen as a denaturant to avoid irreversible precipitation of hemin (15, 16, 17). We then developed a multilayered analysis approach for Hb disassembly based on our recently published measurements and mechanism for GdnHCl-induced unfolding of heme-free apoHb (10) and the new holoHb unfolding data generated in this study (Fig. 2). Our model was used to simultaneously analyze circular dichroism (CD) measurements of secondary structural changes in both apo- and holoproteins and populations of hemin-containing unfolding species. The latter populations were deconvoluted from visible absorbance measurements at different stages of Hb disassembly. Equilibrium disassembly parameters extrapolated to 0 M GdnHCl concentrations were estimated by fitting of our model to measured CD spectral changes and populations of heme-containing intermediates.

Figure 2.

Equilibrium disassembly models of HbA. (A) A structural description of processes occurring in red cells is shown; and (B) a reaction scheme for processes occurring in our unfolding studies is shown. Model 1 includes all the reactions in blue in (A) and (B), whereas model 2 includes the black reactions involving hemin loss from tetramers as well as the blue reactions in (A) and (B). In (A), free hemin is green, and bound hemin is red. Initially, the holoHb tetramer (TH4) disassociates into holoHb dimers (DH2). Alternatively, TH4 can undergo hemin (H) disassociation from the subunits with lower hemin affinity to form the semi-holotetramers (TH2). DH2 can also undergo H disassociation sequentially first to form semi-holodimers (DH), followed by further H disassociation leading to apoHb (D) formation. DH2 unfolds into holo-molten globules (IH2) with hemichrome characteristics. IH2 also can lose H sequentially, first to form semi-holo-molten hemichromes, followed by formation of the apo-molten intermediates (I). IH2 next disassociates and simultaneously unfolds into holomonomers (UH). Loss of H from UH leads to apomonomers (U) with residual helical content. U can either associate nonspecifically with itself to form transient unfolded dimers (U2) or completely unfold into polypeptide chains (UC). The apoHb unfolding mechanism was derived and verified independently in our previous study (10). To see this figure in color, go online. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fatal complications in patients with disassembled or misassembled hemoglobins can result from hypoxia, hemolytic anemias, and iron toxicities due to free hemin release into the blood stream (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25). The pathogeneses of genetic Hb misassembly and instability diseases often originate from accelerated rates of heme loss, disruption of the intersubunit interfaces, and accumulation of unstable intermediates states occurring either on or off disassembly pathways (Fig. 2; (18,23,26)). Our goal was to derive a hemoglobin disassembly mechanism that could provide a framework to examine in detail various adverse events triggered by hemoglobinopathies and to develop targeted therapies.

In their disassembly study of sperm whale holomyoglobin (Mb), which is structurally similar to each Hb subunit, Culbertson and Olson (17) expanded on the apoglobin unfolding scheme originally developed by Baldwin, Wright, Dyson, and their co-workers (27,28) to include steps involving hemin dissociation from holoprotein species. Our overall goal was to apply Culbertson and Olson’s approach for examining quantitatively the effects of hemin binding on the unfolding and disassembly of human holoHb, which is a much more complicated oligomeric system with two types of subunits. We further applied deconvolution methods on visible absorbance spectra to compute the populations of native metHb, partially unfolded hemichrome intermediates, and free dissociated hemin in varying mixtures of GdnHCl and holoHb samples. Hemichromes or hemochromes (ferrous form) are not native conformers in folded Hb (29) and result from the formation of bisaxial coordination of hemin iron to amino acids through combinations of Nε atoms from histidines, S atoms from either methionine or cysteine, and phenoxy O atoms from tyrosine (29). Possible candidate amino acid side chains for axial ligation in the α and β heme pockets are shown in Fig. 1, and all would require structural changes around the heme pocket (for a more complete discussion of HbA hemichromes, see (29)). Similar low-spin visible spectral features as seen in hemichromes are observed at high pH when hydroxide is bound to the hemin iron atom in native metHb, but the pKa for this water-to-hydroxide transition is in the range of 8.1–8.9 (9). Thus, it is unlikely that unfolding in 200 mM phosphate (pH 7.0) would result in hydroxide coordination. In addition, the spectral features for hydroxide-bound metHb are somewhat distinct from those reported for hemichromes (9,29).

Specific roles and biophysical characterization of the hemichromes that form during different stages of Hb disassembly have not been well characterized (30, 31, 32, 33). Our work shows—for the first time, to our knowledge—that 1) heterodimeric hemichromes play a critical role for both α1β1 dimer interface formation and dampening of hemin disassociation during the early stages of disassembly and 2) monomeric and dimeric molten globule hemichromes appear to mediate the major pathway for Hb disassembly at high Hb concentrations in erythrocytes. Our prediction of a predominantly hemichrome-mediated HbA disassembly pathway in erythrocytes helps to explain why hemoglobinopathies have been linked to accumulation of denatured hemichrome precipitates that aggregate into inclusion or Heinz bodies (Fig. 2 A; (18,23,26)).

Our small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) studies confirm that heme binding enables hemoglobin to form the α1β2 interface (Fig. 1) and adopt its functionally compact tetramer conformation. Native human apoHb exists only as a dimer after chemical extraction of hemin (10,34). SAXS intensity measurements were done on both apo and holo forms of the recombinant genetically cross-linked HbA called rHb0.1. The glycine linker between the α chains causes aporHb0.1 to remain as a tetramer (10). However, our SAXS measurements demonstrate that in the absence of heme, the integrity of the tetramer α1β2 interface in rHb0.1 is still disrupted.

Finally, the shift between apo- versus holointermediate-mediated Hb disassembly can be modulated by alterations at the intersubunit interfaces. To verify this idea, we examined fetal hemoglobin (HbF) because of its intrinsically greater resistance to denaturation relative to HbA (35). In HbF, γ subunits are expressed in place of the β subunits (1,36), with amino acid residue differences at the dimer, but not the tetramer, interfaces. The populations of dimeric hemichrome intermediates during the disassembly of holo-HbF are significantly greater than those of holoHbA, which is explained by the increased resistance of the α1γ1 dimer interface to disassociation.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of Hb variants

The molecular biology and protein purification workflow for preparation of holoHb samples were described in our previous work on apoHb unfolding (see (10) and references therein). Native HbA was extracted from expired blood units (Gulf Coast Regional Blood Bank, Houston, TX). Recombinant native HbA and HbF were coexpressed with Escherichia coli Met aminopeptidase from pHE2 and pHE9 E. coli expression plasmids, respectively, in JM109 E. coli cells (Promega, Madison, WI) as described by Shen et al. (37,38). The plasmids were gifts from Dr. Chien Ho’s research group (Carnegie Mellon University). The aminopeptidase post-translationally cleaves the initiator Met residue preceding the V1 residue in each Hb subunit. Recombinant HbA variants with αH58L/V62F and βH63L/V67F mutations were then constructed through site directed mutagenesis using Agilent QuickChange Lightning Kits (Santa Clara, CA).

rHb0.1 has a single-residue glycine linker covalently connecting the N-terminus of the first α1 subunit to the C-terminus of the second α2 subunit. The corresponding non-cross-linked recombinant HbA is known as rHb0.0 (39, 40, 41). Both rHb0.0 and rHb0.1 have a V1M mutation in each subunit to initiate protein expression (10). rHb0.0 and rhHb0.1 were expressed from pDL111-13e and pSGE1.1-E4 expression plasmids, respectively, in SGE1661 E. coli cells (39, 40, 41). These cells and both plasmids were gifts from Somatogen (later Baxter Hemoglobin Therapeutics, Boulder, CO).

Protein expression was induced by 0.2 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside in cells grown either in 500 mL terrific broth in flasks for medium-scale recombinant Hb production, following protocols developed by Ho’s group (37,38), or in a Biostat C 20 bioreactor for large-scale expression, following protocols developed initially by Somatogen (40) and then modified by our group (42). Isolation and purification of native HbA and the recombinant Hbs were done as described previously (37,38,40,42). Cell lysates containing Hb were initially purified using a Zn2+-charged chelating Sepharose Fast Flow resin column (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) because Hb surfaces are rich with His residues that can bind Zn2+ (also see (43)). Further Hb purification was done using a Q Sepharose anion exchange column (GE Healthcare), and a final purification step was done for the Hbs expressed from the pHE2 and pHE9 plasmids using an S Sepharose cation exchange column (GE Healthcare) to eliminate Hbs with uncleaved initiator Met residues. Quality and identify of the purified Hbs, including native HbA isolated from expired blood units, were confirmed by visible absorbance spectra of holoHb forms, isoelectric focusing electrophoresis, electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (1220 Infinity LC system; Agilent). These various analyses are described in previous publications (10,41,44, 45, 46, 47). All hemoglobin samples were stabilized by flushing cell lysates, purified proteins, and all the buffers with pure CO for at least 30 min (47,48) and then stored in their reduced CO forms to prevent autoxidation.

Preparation of metHb, apoHb, and hemichromes

MetHb was prepared by oxidizing HbO2 samples with a slight excess of potassium ferricyanide. HbO2 was initially prepared by flushing HbCO samples with pure O2 for 30 min in a chilled rotating flask that was exposed to an intense industrial light to promote photodissociation of the bound CO (4,47,49).

ApoHb was prepared from metHb according to the method developed by Antonini’s group (50). First, the pH of a concentrated metHb sample was quickly reduced to ∼2.2, followed by extraction of disassociated hemin into cold 2-butanone. Apoglobin recovered from the extraction was then buffer exchanged into 10 mM potassium phosphate, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (pH 7). All ApoHb and metHb samples were prepared and examined at ∼4°C. Reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and gel filtration characterizations of the apoHb samples were reported in our previous publications (10,47).

Hemichrome standards were prepared to obtain their reference spectra (Fig. 3 B). Excess imidazole was added to 12 μM HbA to allow for the binding of imidazole to the hemin iron atom, thereby mimicking the structure of a bishistidine hemichrome. The visible absorbance spectra obtained from this species overlapped with the hemichrome spectra generated by the addition of 600 μM sodium dodecyl sulfate to 12 μM HbA (17,29,51,52).

Figure 3.

Visible absorbance spectra measurements for HbA disassembly. (A) Spectral changes for aquometHbA disassembly induced by GdnHCl and (B) standard spectra for aquometHbA, hemichrome, and free hemin at 12 μM per subunit protein concentration are shown. Unfolding measurements in Fig. 2A were done at 12 μM (per subunit) total protein concentration. All holoHb unfolding measurements were done in 200 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7) at 10°C. Protein samples were initially prepared in aquoMet oxidation states. To see this figure in color, go online.

Measurements of holoHb unfolding

Reaction mixtures at a final and constant buffer concentration of 200 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7) were prepared, consisting of metHb samples in varying concentrations of GdnHCl. As described in our previous publication (10,47), 6 M GdnHCl stock solution was prepared in 200 mM potassium phosphate, with the solution pH adjusted to pH 7. For each metHbA concentration, at least 21 separate reaction mixtures ranging from 0 to 4.8 M GdnHCl were incubated for 1 h in a water bath at 10°C before any spectral measurements. CD and visible absorbance measurements of unfolding were then recorded at 10°C to maintain the solubility of unstable folding intermediates, and these measurements took another ∼2 h because complete spectra were recorded. Thus, on average, the samples were incubated for ∼2 h before measurement. In our initial work with apoHb and our current work with holometHb, we noted that both the CD and visible absorbance changes on addition of GdnHCl were rapid and almost complete after the few minutes it took to inject the Hb, mix the samples, and record the spectra.

In earlier work with holometMb, Culbertson and Olson (17) worried that the rate of hemin loss would be too slow to allow rapid equilibration. However, they observed an ∼100-fold increase in the rate of hemin loss from a metMb mutant as [GdnHCl] was increased from 0 to 0.6 M (17). Assuming a similar effect occurs for hemoglobin, the expected rates of hemin loss should increase from ∼1 h−1 (5) to 100 h−1, which corresponds to half-times of ∼40 to 0.4 min, respectively. Previous work with Met-α chains bound to the α-hemoglobin stabilizing protein (AHSP) showed that hemin dissociates more rapidly from the hemichrome form of the protein (53). In addition, the half-time for tetramer-to-dimer dissociation of liganded and metHb is on the order of 1 s (54,55), and in our previous studies of apoHb unfolding, all the CD changes were complete in several minutes (10,56). Thus, all disassembly processes shown in Fig. 2 should be complete in less than an hour, particularly after the addition of small amounts of GdnHCl. The biggest dilemma was maintaining the temperature of the samples at 10°C during the incubation, transfers to cuvettes, and then the spectral measurements. A further discussion of the reversibility of GdnHCl unfolding measurements is given in the first section of the Supporting Materials and Methods.

The experimental protocols for holometHb closely follow our previous apoHb equilibrium unfolding measurements except for no addition of 1 mM DTT. DTT was added to the apoglobin samples to prevent formation of non-native disulfide bonds, which appeared to occur primarily during the preparation and long-term storage of apoHb as a result of denaturation (10). Very recently, Andre Palmer’s group (57) has reported a new method for rapidly preparing apoHb in which they report no disulfide formation in their newly made apoHb and during storage, and as a result, they did not keep their apoHb samples in DTT. In our work with metHb samples, DTT was observed to cause partial reduction, large visible absorbance changes, and a complicated mixture of oxidation states, including deoxyHb and HbO2. Thus, DTT could not be added for holometHb unfolding experiments. We assume that no significant disulfide formation occurs during our holoHb titrations with GdnHCl based on 1) the new work from Palmer’s group (57) and 2) our own observation of a strong dependence of the second phase of holoHb unfolding on total protein concentration. In our previous work with apoHb unfolding in the absence of DTT, variability was observed for the protein concentration dependence of the second phase, with little dependence being observed for older samples (10).

CD spectral changes were measured using a Jasco J-810 CD spectropolarimeter (Easton, MD), and visible absorbance measurements were measured using a Cary 100 Bio UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Agilent) (10,47). During the CD spectra data collection, the scanning speed was set to 100 nm/min, data pitch was set to 0.1 nm, data integration time was set to 1 s, and spectral bandwidth was set to 1 nm. For the visible absorbance measurements, the data collection interval was 1 nm. Spectra for blank buffer solutions were measured initially to enable baseline corrections for both absorbance and CD measurements using instrument software. For a small portion of the visible absorbance measurements, baseline drifts were observed. For each of the spectra with baseline drift, a new baseline was linearly interpolated from the first 21 points of each spectrum at the longest wavelengths using MATLAB R2017a software (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). The new baseline was then subtracted from the corresponding spectrum.

Visible absorbance spectra at each [GdnHCl] were analyzed in terms of the sum of the matrix multiplication between each species (i) population fraction (Di) and the standard basis spectra (Bi) for the specific i species (Fig. 3 B). Three different i species were considered: folded metHb, hemichrome, and free hemin. Visible absorbance deconvolution was carried out by using the fmincon minimizer in MATLAB R2017a (The MathWorks) to minimize the squared residual difference between the absorbance model spectrum (350–660 nm, 1 nm intervals) at a specific GdnHCl concentration defined in Eq. 1 and the corresponding measured experimental visible absorbance spectrum to determine the population fraction (Di) of each i species.

| (1) |

We chose to use standard reference spectra to characterize the proposed species in Eq. 1, given that the spectral characterizations of the three different species are well distinguished at 0, 1.6, and 4.8 M GdnHCl. Our goal was to determine populations of DH, IH, and free H as independently as possible. When we tried exploratory analyses through singular value decomposition in MATLAB R2017a (The MathWorks), there were intermediate spectral components identified that had no experimental reference. Thus, we choose to use independently determined basis spectra for the sake of experimental validity; however, future refinement of the model may require attempts to delineate between α and β DH and IH components and perhaps even different hemichrome species.

SAXS sample preparations, measurements, and data analysis

Analytical gel filtration was used to verify whether samples were monodisperse. Holo- and apoHb samples were prepared by thorough buffer exchange into degassed 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7), 5 mM DTT. The buffer was degassed and contained DTT to prevent error-causing bubble formation and radiation damage of the protein during data collection. HoloHb samples were also kept in the CO-bound form to further inhibit heme autoxidation during data collection, but no DTT was present (47,58,59).

SAXS measurements of the Hb samples were done using the Rigaku Bio-SAXS 1000 instrument (Tokyo, Japan) at the Sealy Center for Structural Biology and Molecular Biophysics at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, TX. Data were collected at 10°C with 12–16 h of exposure to x-ray radiation, monitored hourly for radiation damage. SAXS measurements of buffer alone were also done to enable blank subtraction. Data collection was done at varying protein concentrations, ranging from 1 to 6 mg/mL. SAXSLab software (Rigaku) was used for data collection, the Small Angle X-ray and Neutron Scattering webserver (http://xray.utmb.edu/saxns) was used for buffer subtraction, and the ATSAS software suite was used for data analysis. From within the ATSAS software, the PRIMUS, almerge, and CRYSOL packages were used for preparation and analysis of the observed x-ray scattering curves, and GNOM was used to generate pair-distance-distribution function P(r) plots (47,60).

Results

Disassembly mechanism of holoHbA

In our model for Hb disassembly, heterotetrameric holoHb TH4 initially disassociates into two holoHb dimers (DH2) without any loss of helical content. In addition to undergoing hemin loss, leading to the apoHb dimer (D) and its subsequent unfolding (right sides of Fig. 2, A and B), the holodimer (DH2) can also unfold into a dimeric holo-molten globule intermediate (IH2), with a hemichrome absorbance spectrum. Molten globules are folding intermediates that are still relatively compact, as in the native state, but exhibit a higher degree of intramolecular motions (61). We have designated the I and IH states as molten globules based on the definition described by Wright and co-workers (28,34,62) for intermediate states of partially unfolded apoMb in which the heme pocket appears to be highly disordered but most of the A, H, and G helices remain intact. We assume that a similar situation occurs for the I-state Hb dimers, for which the α1β1 interface stabilizes the B, H, and G helices (Fig. 1; (10)). The IH states, just like the apo-I states, form during the first phase of Hb unfolding due to the disordering of the heme pockets (Fig. 4, B and D; see Results, Hemichrome-Mediated Resistance to Hemin Disassociation and Subunit Interface Disassembly). The fractional α-helical content of the IH state ranges between 0.4 and 0.6 of the native DH2 state.

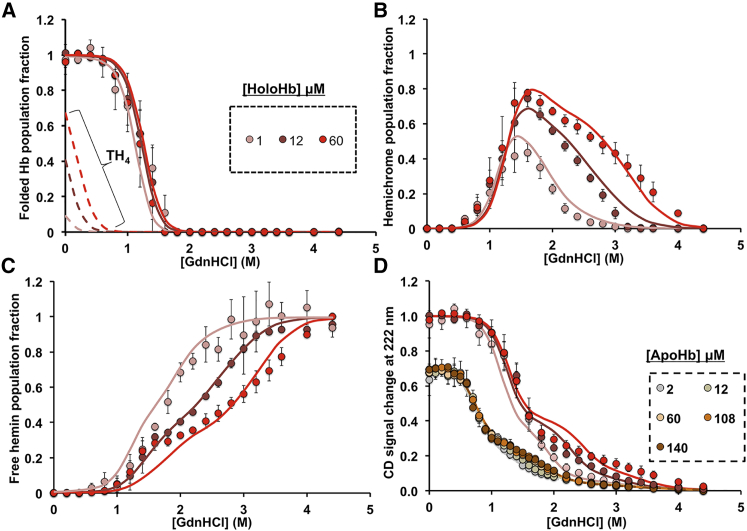

Figure 4.

Fitting of holoHbA GdnHCl-induced disassembly measurements to equilibrium disassembly model 1. The solid circles are the measured data at different per subunit total protein concentration, and the solid lines are the fits to model 1. The dashed lines in (A) are the theoretical population fraction of folded holoHbA tetramers (TH4) derived from the fittings. (A) Population fractions of aquomet-holoHb dimers and tetramers are shown. (B) Population fractions of hemichromes are shown. (C) Population fractions of free hemin are shown. (D) Fractional CD change at 222 nm, which corresponds to the change of α-helical structure content relative to folded holoHbA, is shown. The apoHbA unfolding data (curves at the far left) were previously published (10). The experimental measurements in (A)–(C) were obtained from deconvolution of visible absorbance spectra recorded between 350 and 660 nm. All holoHb unfolding measurements were done in 200 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7) at 10°C, and examples of the hemin spectra and components are given in Fig. 3. Protein samples were initially prepared in aquoMet oxidation states. Each data point is an average of triplicate titrations of protein with denaturant. Each error bar in (A)–(C) represents a population fraction standard deviation obtained from the deconvolution of three independent data sets at each different protein concentration. Each error bar in (D) represents the standard deviation of three independent fractional CD measurements. To see this figure in color, go online.

Each IH2 can further unfold and disassociate into two holo-monomers (UH). We obtained much better fitting to our spectral measurements when we assigned hemichrome absorbance to the UH species, which, like U, appears to have a small amount of residual helical content. This assignment is supported by previous experimental studies, which showed that isolated aquomet-α and β monomers form unstable hemichromes (32,63). Hemin disassociation from UH leads to the formation of apomonomer U states with residual helical content, and then completely unfolded chains, UC, are generated at very high denaturant concentrations.

Complete chemical extraction of hemin from native HbA leads to a heterodimeric apoHb (D) that has undergone 30% helical content loss (10). Our previous studies show that this D state initially unfolds into a molten globule apodimer (I), which has lost 70% of its original α-helical content relative to holoHbA. Next, this molten globule apo-I state disassociates into unfolded monomers (U) with only residual helical content (≤10%). These monomers then can either interact nonspecifically to form transient dimers (U2) or completely unfold into polypeptide chains (UC) (10). The TH4 disassembly scheme in Fig. 2 expands the apoHb model (Fig. 2 B, right side, gray section) to include the binding of hemin (H) to the various D, I, and U states and the formation of hemin-containing tetramers (TH4 and TH2 states in Fig. 2). We did not include the formation of tetrameric apoHb in our models because past studies have shown that native human apoHbs only exist as dimers and not as tetramers in the micromolar concentration range (10,64, 65, 66). The accompanying loss of α-helical content in apoHb due to hemin dissociation is predicted to be occurring around the heme cavity region, which forms the tetramer (α1β2) interface (Fig. 1) and thereby causes Hb disassembly into dimers (10).

Previous studies have shown that native metHbA undergoes noncooperative hemin disassociation, with β subunits having a faster hemin loss rate and presumably lower hemin affinity (5,67, 68, 69). Therefore, we also incorporated noncooperative hemin binding into our model (Fig. 2) by taking into account sequential hemin disassociation from the DH2 and IH2 states. However, we made no assumptions about the relative hemin affinities of the two different types of subunits and assigned an equilibrium constant for each sequential dissociation step. In our model fitting, differences between the subunits would be manifested in the extent of the differences between the first and second hemin dissociation or association equilibrium constants.

In our model, hemin (H) disassociates first from one subunit in DH2, resulting in dimeric semi-holoHb (DH) formation, and then hemin disassociates from DH, leading to the apoHb D state. Similarly, for IH2, hemin disassociation occurs first from one subunit, leading to initial formation of a semihemichrome (IH), and then the next dissociation leads to formation of the apo-molten globule (I). Past studies have suggested the semi-holoHb formation occurs by either hemin disassociation from the β subunits in holotetramers or holodimers or, alternatively, by initial hemin binding to α subunits in apoHbs (68,70).

Given the weak affinity of hemin for unfolded proteins (15,17,71,72), the lack of structural evidence about unfolded states, and the limitations of spectroscopic measurements, we assumed no differences in hemin affinity between α versus β variants of U monomers (KU,UH) (Fig. 2). Nonspecific hemin binding to the U2 and UC could not be accurately defined because only free hemin visible absorbance spectra are observed after the loss of all helical content in the unfolded monomers.

All of these reversible disassembly stages were incorporated into our overall scheme and are represented by model 1 (blue arrows) in Fig. 2, A and B. We also considered an additional step involving semi-holotetramer formation, which was incorporated into model 2 (both blue and black arrows in Fig. 2, A and B). In this second model, TH4 undergoes disassociation of two hemin molecules initially from the subunit type with lower hemin affinity to form tetrameric semi-holoHb (TH2), which then dissociates into a semi-holodimer (DH).

Spectroscopic measurements of holoHb disassembly

GdnHCl-induced disassembly of metHbA (Figs. 3 and 4) and metHbF (Figs. 5 and S1) was examined as a function of total protein concentration by measuring simultaneously both heme visible absorbance and protein CD spectral changes. With increasing denaturant concentration, holoHb unfolds and undergoes both hemin disassociation (Figs. 3, 4 C, and 5 C) and loss of α-helical content. CD signal changes at 222 nm were used as a measure of the fraction of α-helical content present in the protein relative to that of folded holoHb (Figs. 4 D and 5 D; (10)). The changes in hemin absorbance spectra were used to compute populations of the various holo species during disassembly and free hemin (H) as described in Materials and Methods.

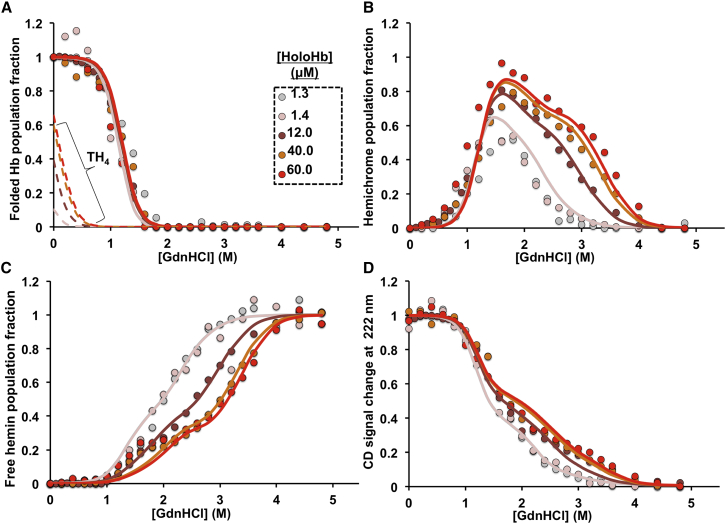

Figure 5.

Fitting of holoHbF GdnHCl-induced disassembly measurements to equilibrium disassembly model 1. The solid circles are the measured data at different per subunit total protein concentration, solid lines are the fits, and dashed lines are the theoretical population fraction of folded holoHbF tetramers (TH4) derived from the fittings. (A) Population fractions of aquomet-holoHb dimers and tetramers are shown. (B) Population fractions of hemichromes are shown. (C) Population fractions of free hemin are shown. (D) Fractional CD change at 222 nm, a measure in the change of α-helical structure content relative to folded holoHbF, is shown. The experimental measurements in panels (A)–(C) were obtained from deconvolution of visible absorbance spectra recorded between 350 and 660 nm. All holoHb unfolding measurements were done in 200 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7) at 10°C, and the observed visible spectral changes are given in Fig. S1. Protein samples were initially prepared in aquomet oxidation states. The 12 μM Hb CD unfolding measurement was obtained from previously published data (10). To see this figure in color, go online.

As shown in Fig. 3 A for metHbA, we observed dramatic shifts in the heme visible absorbance spectra as holoHb disassembles with increasing GdnHCl concentrations. Initially, at low [GdnHCl], the observed visible absorbance spectra were characterized by features that are unique to high-spin aquometHb (Fig. 3 B), including a sharp, dominant Soret absorbance peak at 405 nm and additional smaller peaks at 500 and 630 nm. At high [GdnHCl], when only residual (≤10%) or no α-helical content remains (Figs. 4 D and 5 D), the absorbance spectra were characterized by features that are unique for high-spin free hemin in solution, including a broad Soret absorbance peak around 370 nm and additional smaller peaks around 510 and 630 nm (Figs. 3 and S1; (4,17,73, 74, 75)). During intermediate stages of Hb disassembly, another distinct absorbance spectrum appears and is indicative of a low-spin hemichrome (Figs. 3, 4 B, 5 B, and S1). Hemichrome absorbance spectra are characterized by a distinct and narrow red-shifted Soret absorbance peak around 413 nm and Q bands or visible region peaks at 535 and 565 nm (Fig. 3 B; (17,29,51,76)).

As described in Materials and Methods, we deconvoluted the heterogeneous visible absorbance spectral curves at intermediate [GdnHCl] using the three standard spectra for native aquomet, hemichrome intermediate, and free hemin shown in Fig. 3 B. The differing population fractions of these species were computed as the GdnHCl titrations proceeded; the results for aquometHbA are shown in Fig. 4, A–C, and for aquometHbF in Fig. 5, A–C. The hemichrome population reaches a maxima at the beginning of the second phase of unfolding, corresponding to when the protein has lost ∼60% of its α-helical content and forms a molten globule (Figs. 3 A, 4, B and D, and 5, B and D).

Hemichrome-mediated resistance to hemin disassociation and subunit interface disassembly

As shown in Fig. 4 D, the CD curves shifted toward higher [GdnHCl] in the presence of bound hemin in HbA (and in HbF; see (10)). This shift demonstrates the higher stability of holoHb relative to apoHb (10). Previously, we had determined that during apoHb unfolding, the first phase involves unfolding of the heme pocket, whereas the second phase corresponds to the dissociation of the heterodimeric molten globule (10). For apoHbs, the protein concentration dependence of the second phase of unfolding demonstrated that it represents disassociation of the α1β1 and α1γ1 dimeric molten globules into unfolded monomers (10). The same interpretation applies to the unfolding curves of holo-HbA and HbF in this study. Again, increasing protein concentration shifts the second phase for loss of α-helical content to higher [GdnHCl] (Figs. 4 D and 5 D). Similarly, the loss of hemichrome populations (Figs. 4 B and 5 B) and the appearance of free hemin (Figs. 4 C and 5 C) are shifted toward higher [GdnHCl], demonstrating that there is greater resistance to both hemin and dimer disassociation with increasing protein concentration. These CD and visible absorbance results demonstrate that bound hemin in the hemichrome state strengthens the α1β1 and the α1γ1 interfaces in the molten globule intermediate.

In our previous studies on apoHb unfolding, we determined that the α1γ1 dimer interface in HbF is more resistant to dissociation than the α1β1 interface in HbA, with a monomer-to-dimer association constant (KUI) of 8.4 × 109 M−1 for HbF compared to 6.6 × 108 M−1 for HbA (Table 1; (10)). Correspondingly, the HbF hemichrome population showed a higher resistance to hemin disassociation during the second phase of unfolding than the HbA IH and IH2 populations (Figs. 6 B and S2 B). rHb0.1, the recombinant variant of HbA with a glycine cross-linker between the α subunits, has an even larger hemichrome population at high [GdnHCl], which is greater than that for both HbA and HbF (Fig. 6 B). The covalently cross-linked aporHb0.1 tetramer has been previously shown to be much more resistant to disassembly during the second phase of unfolding because two α1β1 interfaces have to be disrupted in rHb0.1 to generate two unfolded β monomers and a di-α subunit (10).

Table 1.

Fitted Equilibrium Disassembly Parameters for HbA and HbF

| Parameter | HbA | HbF |

|---|---|---|

| K2,4(M−1)a | 1.0 × 105 | 1.0 × 105 |

| KDH,DH2 (M−1) | (1.1 ± 1.4) × 1010 | (1.3 ± 8.5) × 1011 |

| KD,DH (M−1) | (1.6 ± 2.1) × 1011 | (2.5 ± 16) × 1011 |

| KIH,IH2 (M−1) | (3.2 ± 0.5) × 108 | (1.4 ± 0.1) × 109 |

| KI,IH (M−1) | (1.1 ± 0.8) × 1011 | (7.8 ± 0.4) × 1011 |

| KU,UH (M−1) | (2.8 ± 0.2) × 107 | (8.4 ± 0.4) × 107 |

| m2,4(kJ mol−1M−1) | 20.0 ± 206 | 20.0 ± 183 |

| mDH,DH2 (kJ mol−1 M−1) | 10.3 ± 0.1 | 9.9 ± 0.1 |

| mD,DH (kJ mol−1 M−1) | 10.3 ± 0.1 | 9.9 ± 0.1 |

| mIH,IH2 (kJ mol−1 M−1) | 10.3 ± 0.1 | 10.7 ± 0.04 |

| mI,IH (kJ mol−1 M−1) | 10.3 ± 0.1 | 10.7 ± 0.04 |

| mU,UH (kJ mol−1 M−1) | 5.0 ± 0.05 | 5.2 ± 0.04 |

| STH4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SDH2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SDH | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| SIH2 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.03 |

| SIH | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 0.34 ± 0.03 |

| SUH | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.30 ± 0.04 |

| KI,Db | 164 ± 3 | 128 ± 11 |

| KU,Ib (M−1) | (6.6 ± 0.1) × 108 | (8.4 ± 2.2) × 109 |

| KU2,Ub (M) | 5.6 × 10−7 | 1.7 × 10−8 |

| KUC,Ub | 1190 | 921 |

| mI,Db (kJ mol−1 M−1) | 16.2 | 17.5 |

| mU,Ib (kJ mol−1 M−1) | 11.6 | 12.7 |

| mU2,Ub (kJ mol−1 M−1) | −3.9 | −6.8 |

| mUC,Ub (kJ mol−1 M−1) | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| SDb | 0.70 | 0.73 |

| SIb | 0.30 | 0.33 |

| SUb | 0.062 | 0.08 |

| SU2b | 0.015 | 0.02 |

| SUCb | 0.0024 | 0.006 |

The disassembly parameters for holoHb were fitted to model 1 as described in the text.

The standard errors from the fitting analyses were computed as described in the second section of the Supporting Materials and Methods. Values of K2,4 and m2,4 are undefined because tetramer-to-dimer dissociation becomes complete after the first or second addition of denaturant. Thus, values were italicized. In effect, K4,2 was left at the experimentally reported value (77), and m2,4 had to be large, ≥∼20, but was also undefined as noted by its large standard error.

Parameters for the apoHb part of the disassembly were fixed to values determined in our previously published work (10).

Figure 6.

Comparison of GdnHCl-induced equilibrium unfolding measurements of holoHbA, HbF, rHb0.1, and Hb α(H58L/V62F)β(H63L/V67F). The solid circles are the measured data at 12 μM per subunit total protein concentration. (A) Population fractions of Met-holoHb dimers and tetramers are shown. (B) Population fractions of hemichromes are shown. The experimental measurements were obtained from deconvolution of visible absorbance spectra recorded between 350 and 660 nm. All holoHb unfolding measurements were done in 200 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7) at 10°C. All holoHb samples were converted to the Met oxidation state just before the titrations. To see this figure in color, go online.

For both holoHbA and HbF, protein concentration dependency was not observed during the first phase of unfolding either in the CD curves or in the population fractions of the heme spectral species (Figs. 4 and 5). Hemichromes start to appear during the first phase and, in fact, seem to be playing a key role in reducing hemin loss during the early disassembly stages for both HbA and HbF (i.e., little free hemin is present until [GdnHCl] ≥ 1.5–2 M). If significant hemin disassociation had been occurring from folded metHb or the newly formed hemichromes, we should have observed population shifts in the curves for native aquometHb and changes in the first phase for the appearance of free hemin as the protein concentration increased (Figs. 4, A and C and 5, A and C). Instead, conformational changes around the heme pocket region during the first phase promoted a high-spin metHb to low-spin hemichrome transition, with heme still bound in the protein. This conformation change is likely induced by both the loss of α-helicity and increasing disorder around the heme pocket region and is similar to what occurs during the first phase of apoHb unfolding (10).

We initially expected to see a dependence on protein concentration for the initial phase of the CD change because of holotetramer-to-holodimer dissociation. However, none was observed, which is due to the large tetramer-to-dimer dissociation constant of aquometHb, which is ∼10 μM (77). The threshold of the CD photomultiplier limited the range of holoprotein concentrations to be examined. Within the smaller range that we could examine (1 to ∼60 μM total heme), our modeling (Fig. 2) predicted that the tetramer-to-dimer disassembly was occurring at very low denaturant concentrations before any significant heme pocket unfolding or hemin dissociation occurred. However, if we could have carried out experiments in the millimolar Hb concentration region, our model does predict that we would observe protein concentration effects during the first phases of disassembly (see the Results, Modeling HbA Disassembly in Erythrocytes and in Blood Plasma).

The E7 histidine is the nearest amino acid that can coordinate with the hemin iron on the distal side of the porphyrin ring in Hb. HisE7 stabilizes exogenous ligands bound to heme iron through hydrogen bonding with the Nε2 atom. However, the Nε2 atom is still at a nonbonding distance of ∼4.1 Å from the hemin iron in native metHbA, and a water molecule is coordinated instead (Fig. 1; (29,78)). We assume the major hemichrome species during native HbA disassembly is most likely due to hemin iron hexacoordination to both the F8 and E7 histidine. However, to the best of our knowledge, no direct structural evidence for this assumption exists. Other amino acid side chains (Met, Tyr, Cys) could coordinate to the iron atom if the C, E, and F helices and the CD, EF, and FG corners have either unfolded or undergone increased internal motions (see Fig. 1).

Different combinations of axial ligands for hemichrome formation must occur because hemichrome spectra are still observed for the recombinant metHb α(H58L/V62F)β(H63L/V67F) quadruple mutant, in which both distal histidines were replaced with leucines (Fig. 6 B). However, the population fractions of the hemichrome intermediate formed during disassembly of the mutant are roughly half that observed for native HbA, implying less stable hexacoordination (Fig. 6 B). In addition, the standard basis spectrum for folded recombinant metHb α(H58L/V62F)β(H63L/V67F) is different from that of aquometHbA because of the absence of coordinated H2O at the hemin iron (79). For the mutant relative to aquometHbA, the Soret peak is blue shifted to 400 nm, and the smaller peak at 630 nm is shifted to 600 nm (Fig. S3). In contrast, the hemichrome spectrum for the LeuE7-containing HbA mutant is very similar to that for the HbA and HbF hemichrome intermediates. The presence of the hemichrome species in the LeuE7 Hb mutant also argues against a hydroxide-bound, low-spin species, which requires stabilization by hydrogen bonding to the HisE7 side chain (79). This mutant also showed increased hemin disassociation during the initial phase of disassembly (Figs. 6 A and S2 B). Past studies of HisE7-to-Leu mutations in both Hbs and Mbs attributed the marked increases in rates of hemin dissociation to loss of hydrogen bonding between the HisE7 side chain and the coordinated H2O molecule (Fig. 1; (45,80)). Our new results suggest that the role of hemichrome formation should also be considered when interpreting rates of hemin dissociation for different Hb variants because hemichromes are clearly intermediates in holoHb disassembly. Culbertson and Olson (17) came to similar conclusions about the role of hemichromes in holoMb disassembly and also observed this spectral intermediate during the unfolding of a metMb HisE7-to-Phe mutant.

Deriving disassembly parameters

The assembly constants defined in Fig. 2 B and listed in Table 1 were obtained by extrapolation to 0 M GdnHCl concentration or x and are represented by the K0-values in Eqs. 2 and 3. This extrapolation was done using the dependence of the K constants on [GdnHCl] or x as shown in Eqs. 2 and 3. This assumption of a linear free-energy dependence on the concentration of GdnHCl is a caveat of our analyses and those of others in the field (81). It should also be noted that interactions between the guanidinium and the polypeptide backbone, overall ionic strength, and osmolarity of the solvent phase are increasing during the titrations, which we assume are all part of the linear dependence of the unfolding free energy on [GdnHCl] represented by the m-values.

The apoHb folding constants in Eq. 3 and Table 1 were taken from our earlier work (10). The m-values describe the dependence of the assembly free energies on [GdnHCl] and absolute temperature (T) and allow extrapolation to [GdnHCl] = 0. The K parameters containing H subscripts in Eq. 2 define hemin binding to the various apo subunits in Fig. 2 B (except KTH4,TH2, which defines hemin disassociation), and K2,4 defines the holometHb dimer to tetramer association equilibrium constant.

| (2) |

For our overall Hb disassembly and assembly scheme described in model 1 (Fig. 2), the theoretical values of total protein concentration [P] on per subunit basis and total free hemin concentration [free hemin] in solution were computed from the concentrations of the various species in Eqs. 4 and 5, respectively. This theoretical [P] value should equate to y, the experimentally defined Hb concentration on a per subunit basis. Because there is no excess hemin in the original solutions, [free hemin] in Eq. 5 will equate to [H] in Eq. 2. [Free hemin] in Eq. 5 is computed from the sum of the concentrations of the apo subunits in all the apo and semi-holo species. For the alternative model 2 that included semi-holotetramers, [P] and [free hemin] were rederived with the addition of the terms 4[TH2] and 2[TH2] to the right sides of Eqs. 4 and 5, respectively.

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

The general population fraction Yi on per subunit basis for a specific folding species (i) is described in Eq. 6, in which specific examples are given for the free hemin fraction (YH) and holoHb tetramer population fraction (YTH4) from model 1. The total population fraction of folded holoHbs, encompassing both the holoHb dimers and tetramers, is defined as YFolded holoHb = YTH4 + YDH2 + 0.5YDH for model 1 and YFolded holoHb = YTH4 + YDH2 + 0.5(YTH2 + YDH2) for model 2. In both models, the total population fraction of hemichromes was evaluated as YHemichromes = YIH2 + 0.5YIH + YUH.

The theoretical YFolded holoHb-value was assumed to correspond to the population fraction of native metHb spectral species (red spectrum in Fig. 3 B) derived experimentally from deconvolution of the measured visible spectra as a function of [GdnHCl] (Eq. 1). YHemichrome and YH were assumed to correspond, respectively, to the fractions of low-spin hemichrome spectrum (blue spectrum in Fig. 3 B) and high-spin free hemin spectrum (green spectrum in Fig. 3 B) in the measured visible absorbance data. A weight of 0.5 was assigned to the semi-holoHb Y-values in the expressions for YHemichrome and YFolded holoHb to account for the subunits present that already had undergone hemin disassociation. The theoretical normalized total CD signal, STotal, represents the fractional α-helicity measured at 222 nm relative to that for folded holoHb. STotal was defined as the sum of the product of Yi and the intrinsic normalized CD signal Si for each folding species (not including free hemin), as shown in Eq. 7. Si is independent of x and y and is defined as the fraction of α-helical content of species i relative to folded holoHb.

| (6) |

| (7) |

The K-, m-, and Si-values characterizing holoHb unfolding were estimated by global fitting of 1) specific Yi- or sums of Yi-values to the corresponding measured populations of native metHb, hemichrome, and free hemin obtained from deconvolution of the visible spectral data; and 2) STotal to the experimental CD values that were normalized against the α-helical content of folded holoHb (Figs. 4 and 5; Table 1). The fits to these experimental measurements were done as a function of x (GdnHCl concentration) and y (total protein concentration) variables for both holoHbA and holoHbF. The K-, m-, and Si-values for the apoHb unfolding steps were fixed to the values determined from our previous independent apoHb unfolding studies (10,17). The m-values for the association constants for hemin binding to folded heme pockets were set equal to each other (e.g., mDH,DH2 = mD,DH), and the m-values for the parameters describing hemin binding to the molten dimers were also set equal to each other (e.g., mIH,IH2 = mI,IH) (Table 1; Table S1).

The K2,4-value for the metHbA dimer-dimer association was initially set to 1 × 105 M−1 based on previous studies (77). Because there is no protein sequence difference at the tetramer interface between HbA and HbF, the same K2,4-value was used for HbF. This number did not change much during the model fittings. The lack of change was likely due to 1) the absolute value of K2,4 being poorly defined but in the 1 × 105 M−1 range and 2) tetramer dissociation being complete at very low denaturant concentrations ([GdnHCl] ≤ 0.5 M).

The Yi-values had to be computed first by defining them in terms of the K constants at different x- and y-values (left sides of Eqs. 2 and 3) for comparison with the experimental data. For this purpose, [U]- and [H]-values at a given x and y were obtained by numerically applying Newton’s method (82) for systems of nonlinear equations (Eqs. 8 and 9) expanded from the definitions of [P] (e.g., Eq. 4) and [free hemin] (e.g., Eq. 5). As shown for model 1 in Eqs. 8 and 9, all species were expanded only in terms of [U]-, [H]-, and K-values. The initial values of [U] and [H] obtained numerically were then used to compute new values of Yi.

Starting from these initial estimates of Yi, lsqcurvefit function (a nonlinear least-squares solver) in MATLAB R2017a (The MathWorks) was applied to globally fit the theoretical models to the experimental measurements as shown in Figs. 4, 5, and S4. An algorithm was written in MATLAB R2017a (The MathWorks) to apply the numerical analysis method and fitting function in an iterative loop in which the K, m, and Si parameters updated from each optimization loop were fed back to the numerical analysis part of the algorithm to obtain a new set of [U]- and [H]-values. The implementation of the loop is stopped when the best fit between the experiment and model is reached as defined by a minimal steady value of χ2, the squared residual difference between the models and experimental measurements.

| (8) |

| (9) |

Our overall disassembly model 1 (Fig. 2, blue arrows) was fitted to HbA unfolding data (Fig. 4) using the optimized parameters in Table 1. A χ2-value of 0.74 was obtained. Model 2 was proposed to try to determine the hemin binding constant for the low-affinity subunit (probably β chains) in tetrameric HbA (Fig. 2). When HbA unfolding data were fitted to model 2 (Fig. S4; Table S1), there were only small changes in the goodness of the fit (χ2 = 0.69). More importantly, the population fraction of semi-holo tetramers, with hemin disassociated from the low-affinity subunits, was always close to 0 (Fig. S4 A, inset). Even this more complex scheme indicated that small amounts of GdnHCl were sufficient to disrupt the weak holotetramer interface before any significant unfolding or hemin dissociation occurs at the protein concentrations that were accessible to our spectral measurements (dashed lines in Figs. 4 A and S4 A).

When model 2 was simulated later at high protein concentrations (approximately micromolar range) (see next section and Fig. S4 A), the population of semi-holotetramers was still almost 0. This result also suggests that semi-holotetramers are not a predominant species during HbA assembly, and heme insertion is occurring much earlier during dimer assembly (see Discussion). Furthermore, other kinetic studies have documented that hemin loss rates increase dramatically when Hb tetramers dissociate into dimers (5,7,46). Thus, we chose to consider only the simpler model 1, in which complete dissociation of holotetramers into dimers occurs before either hemin loss or unfolding.

This model (Fig. 2) predicts sequential binding of hemin to the apodimer with association equilibrium constants equal to KD,DH = 1.6 × 1011 M−1 for the first step and KDH,DH2 = 1.1 × 1010 M−1 for the second step. By considering the binding sites to be noninteracting with each other, we interpret these constants in terms of a two-step Adair binding equation (83) to evaluate the intrinsic hemin affinity per subunit. In this case, the intrinsic hemin affinity per subunit for the first step is 1/2 × KD,DH or 5.5 × 1010 M−1, and the intrinsic affinity per subunit for the second step is 2KDH,DH2 or 2.1 × 1010 M−1. This ∼2-fold decrease in hemin affinity could be due to either negative cooperativity or differences in hemin binding to the α versus β subunits, but the uncertainties in the fitted values are ∼±100%, making a specific interpretation difficult. The noncooperative subunit differences interpretation is the most reasonable because we and others (5,67, 68, 69) have shown that the rate of hemin dissociation from β subunits is higher than that from α subunits in metHbA. Therefore, these intrinsic hemin affinities can be interpreted to indicate that the initial loss of hemin from the native folded dimer comes primarily from the β subunit generating the semi-holo DH state with a majority of hemin still in the α subunit. Regardless of the exact interpretation, the fitted values for hemin binding to the D state are very similar to the values estimated from measured dissociation rate constants, ∼1011 M−1 s−1, by Hargrove et al. (5).

Hemin binding to the apo molten HbA dimer (I in Fig. 2 B) also occurs sequentially, and in this case, the difference in hemin affinity between the first and second steps is even larger, with KI,IH = 1.1 × 1011 M−1 and KIH,IH2 = 3.2 × 108 M−1 (Table 1). In this case, the intrinsic subunit affinity for the first step is 1/2KI,IH = 5.5 × 1010 M−1 and almost equal to that for the first step in hemin binding to the native D state. In contrast, the intrinsic affinity for the second step is only 2KIH,IH2 = 6.4 × 108 M−1. This large decrease in affinity suggests the subunit differences increase ∼30-fold in the molten intermediate relative to the folded state, and in this case, the uncertainties in the fitted parameters are much less (Table 1). Based on the known higher hemin loss rates from the β subunit in folded metHbA (5,67, 68, 69), it appears likely that its affinity for hemin is even lower in the molten or hemichrome I state.

Unfolded apo- and holomonomers at high [GdnHCl] have only residual α-helical content, ranging between ∼10 and 20% relative to folded HbA subunits (Table 1; (10)). Thus, as expected, the fitted hemin affinity constant for these unstructured monomers is small (KU,UH = 2.8 × 107 M−1) (Table 1) and likely dominated by nonspecific interactions (Table 1; (15,17,71,72)).

As shown in Fig. 5, we were able to analyze successfully holoHbF unfolding data with the same model 1. In this case, a somewhat higher χ2-value of 1.67 was obtained. In folded HbF dimers, the hemin affinity for the first and second steps in hemin binding were more similar, with KD,DH = 2.5 × 1011 M−1 (intrinsic subunit affinity, 1.3 × 1011 M−1) and KDH,DH2 = 1.3 × 1011 M−1 (intrinsic subunit affinity, 2.6 × 1011 M−1) indicating noncooperative binding and few or no subunit differences. Once more, the uncertainties in the fitted values were large, indicating that the parameters are poorly defined. However, the affinities of the first and second steps for binding to the HbF molten intermediate are quite different, with KI,IH = 7.8 × 1011 M−1 (intrinsic subunit affinity 3.9 × 1011) and KIH,IH2 = 1.4 × 109 M−1(intrinsic subunit affinity 2.8 × 109 M−1). Again, it seems that the γ subunits have a lower hemin affinity in the molten globule intermediate because the first I-state hemin affinity constant for HbF appears similar to that of α subunits in HbA. The U monomers for HbF also had ∼10-fold higher hemin affinity than in HbA, and the holomonomers UH had slightly higher α-helical content at 30% relative to folded HbF (Table 1). Regardless of the exact interpretation, it is clear that one of the hemichrome-containing subunits in the molten dimer states of both HbF and HbA has a relatively high affinity for hemin, which is similar to that in the folded D state and probably represents α subunits. However, without more experimentation, this conclusion is speculative.

Modeling HbA disassembly in erythrocytes and in blood plasma

During maturation of red blood cells, all of the membrane organelles in the cytoplasm, including the nucleus and mitochondria, are eliminated to allow for dense packing of hemoglobin to a concentration of ∼20 mM per subunit (84, 85, 86). At these high concentrations, native oxyHb exists almost completely as holotetramers because the tetramer-to-dimer disassociation constant (K4,2 or 1/K2,4) is on the order of 10−6 M, and the corresponding value for deoxyHb is even lower, on the order of 10−12 M (77,87,88).

If oxidative stress occurs in erythrocytes because of genetic disorders, environmental chemicals, or drugs, denaturation of the resultant metHb can occur in the cell cytoplasm. At these high hemoglobin concentrations, the major disassembly pathway will be dominated by holoprotein intermediates, represented by the left side of Fig. 2. To illustrate this effect quantitatively, we computed the population fractions of all the intermediates for a GdnHCl-unfolding titration at 20 mM total protein, using the parameters in Table 1 (Fig. 7, A and B). The initial step involves dissociation of holotetramers into holodimers, which is followed by unfolding into molten holodimers with hemichrome spectra. This IH2 species is the dominant intermediate with small amounts of the semi-holo-molten globule, IH. The IH2 and IH species predominantly dissociate into unfolded holomonomers before any significant hemin loss occurs. The high Hb subunit concentration inhibits dissociation of both the dimeric intermediates and bound hemin. Even the loss of weakly bound hemin from unfolded monomers is inhibited until very high [GdnHCl]. When model 2 and the parameters in Table S1 were used to simulate the population fractions at 20 mM Hb, the same conclusion on the dominant role of holoprotein intermediates is reached (Fig. S5, A and B).

Figure 7.

Simulated HbA disassembly population fractions. (A and B) Hb packed in red blood cells and(C and D) Hb in dilute blood plasma. The results demonstrate Hb concentration directed disassembly pathways. Simulations were done using model 1 (Fig. 2) and the parameters in Table 1 as a function of [GdnHCl]. To see this figure in color, go online.

Hemolysis of red cells leads to the release of hemoglobin into plasma and can be triggered by hemoglobinopathies, red cell aging, oxidative stress, blood infections by heme-iron-extracting pathogens, complications during cardiovascular medical procedures, and blood transfusions. Dilution into the large volume of plasma leads to very low, micromolar Hb concentrations, which causes almost complete disassociation of tetrameric Hb into dimers and acceleration of autoxidation (6,89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94). Thus, when hemoglobin is diluted into plasma after red cell lysis, metHb formation occurs, and dissociation of both the intersubunit interfaces and hemin are facilitated. This situation was simulated in Fig. 7, C and D using the parameters in Table 1 and 0.5 μM total protein. The disassembly pathway is quite different from that in red cells. The initial holoprotein is primarily a dimer, DH2 (Fig. 7 C), and the dominant intermediates are the semi-holo-molten dimer, IH, and the apo-unfolded U monomer until the completely unfolded chains, UC, are formed. Perhaps the most striking difference between the red cell versus plasma pathways is the early appearance of free hemin before unfolding is finished (Fig. 7 D). At low Hb concentration, dissociation of the α1β1 dimer interface is facilitated, resulting in low populations of the molten dimer hemichromes. Hemin dissociation is also facilitated, leading to predominantly apointermediates and unfolded chains even before the end of the simulated titration.

SAXS analysis of apoHb properties in solution relative to holoHb

SAXS intensity measurements (Fig. 8) were done on both apo and holo forms of recombinant cross-linked HbA or rHb0.1 and also on the holo form of the corresponding non-cross-linked rHb0.0 (39, 40, 41). Cross-linking causes aporHb0.1 to remain a tetramer under conditions in which native apoHb is a dimer (10). We chose the aporHb0.1 variant for SAXS analysis to have a covalently cross-linked tetramer as standard for the radius of gyration (Rg) for holo-Hb tetramers. The SAXS measurements were fitted to the Guinier plot equations (Fig. 8, inset) to obtain Rg for each molecule. Minor effects of molecular crowding were only observed for aporHb0.1, occurring at protein concentrations >1.5 mg/mL (Fig. S6). For aporHb0.1, Rg and the pair-distance-distribution function P(r) between atoms were determined with SAXS scattering measurements extrapolated to infinite dilution to remove the molecular crowding effects (Figs. 8, S6, and S7; (95)). AporHb0.1 at 0.0 mg/mL exhibited an Rg of ∼29.4 Å, whereas for the holo forms of rHb 0.0 and rHb0.1, the experimental Rg-values are both ∼24 Å, as expected from their known crystal structures (e.g., PDB: 1O1L) (Figs. 8 and S6). Thus, aporHb0.1 is expanded in solution. These kinds of expansions are often observed for partially unfolded proteins (95) and support our view that hemin dissociation causes loss of the ability of hemoglobin to form compact and cooperative tetramers. The losses of helical content are likely occurring around the heme cavity regions, which also form the α1β1 tetramer interface, allowing expansion of the cross-linked protein.

Figure 8.

SAXS Log intensity profiles and Guiner plot (inset) for recombinant Hbs. For the log-log plots, the samples shown are the zero-concentration extrapolated aporHb0.0 (green), 2.0 mg/mL Hb0.1 (blue), and 2.0 mg/mL Hb0.0 (red). Inset: the Guinier plots with their residuals (darker lines) and (1.3/Rg) Guinier q-upper limits (dashed lines for Rg = 29.4, 24.3, 23.6 Å) are shown. The expansion of the apoprotein is obvious from the less distinct minima in the higher angle data. To see this figure in color, go online.

Interestingly, our SAXS measurements also suggest that this loss of helical content due to hemin dissociation increases the susceptibility of Hb to molecular crowding. Similar effects of molecular crowding might occur for the partially disordered assembly intermediates and during early folding events for Hb in vivo. With more sticky regions of unfolded chain segments exposed and expanded in solution, there is also a higher probability they can come in closer contact and even interact weakly with the other protein molecules causing the crowding.

Discussion

Global disassembly pathway for human hemoglobin

Heterotetrameric hemoglobins evolved from monomeric vertebrate Mbs within the globin metalloprotein family ∼600 million years ago (1,96,97). In this work, we have shown for the first time, to our knowledge, that human Hb shares a common disassembly pathway with mammalian Mb. For both systems, hologlobin disassembly is mediated via a molten hemichrome intermediate. However, relative to the simpler Mb monomer system (17,27,28), the human Hb assembly and disassembly mechanism evolved to be much more complex. This complexity is demonstrated by the multiple steps for heme binding to dimeric intermediates and by the sequential formation of the dimer (α1β1) and then tetramer (α1β2) interfaces (Fig. 2).

To the best of our knowledge, no one has previously tried to analyze reversible holoHb disassembly quantitatively with a comprehensive model, probably because of its complexity. In addition, most studies involved thermal denaturation (98, 99, 100), which leads to precipitation of both the globin chains and free hemin in conventional buffers. To our knowledge, this study is also the first attempt to measure equilibrium hemin binding parameters for human HbA and provides reasonable estimates for comparison with previous kinetic studies (5,99,101). We were also able to estimate heme binding parameters at different stages of Hb assembly and disassembly independently and characterize how they influence intersubunit assembly and globin folding. Determination of hemin affinity constants is not possible by direct titration of apoglobins with hemin because free hemin stacks to form dimers and higher molecular weight aggregates even in the micromolar region (75). In our experiments, the hemin equilibrium binding constants were obtained by simultaneously analyzing GdnHCl-induced unfolding curves for both apo- and holo-Hb to avoid problems associated with apoglobin and hemin precipitation.

Hargrove et al. (101) had previously concluded that the association rate constant for hemin binding to apoglobin seems to be relatively invariant and ∼1 × 108 M−1 s−1 per subunit regardless of the globin structure for either apoHb or apoMb. Past kinetic studies were focused mostly on measuring heme disassociation rates from the end-state products of Hb assembly, e.g., TH4 and DH2 (Fig. 2; (5,102)). However, such kinetic studies did not attempt to consider how these rates and hemin affinities change as unfolding proceeds via molten globules with significant reconfigurations of the hemin pockets.

The approaches that led us to successfully resolve “new” holointermediates and their roles in disassembly were 1) deconvolution of visible absorbance signals into various intermediate-hemin-containing populations, 2) model fitting to both apo- and holoprotein unfolding spectral measurements, and 3) examination of the protein concentration dependency of bimolecular events involving both intersubunit interactions and heme binding. We also developed a model evaluation approach that incorporates numerical analysis methods to solve for disassembly populations and takes into account the complexity of the Hb protein with four subunits and four bound hemin molecules. For monomeric heme proteins, more straightforward quadratic equations can be used to solve for fractions of various holo- and apointermediates (17,73).

Physiological relevance

The results in Fig. 7, A and B can provide insights for the assembly pathway at various protein and heme concentrations during hemoglobin biosynthesis. First, hemin binding is a bimolecular process and required for tetramer assembly. Therefore, at high heme and protein concentrations, the fraction of the holo-molten globule and native dimers will outcompete their apo counterparts to promote tetramer formation. In addition, at these high concentrations, weak hemin binding to U monomers might be interpreted as an induced fit mechanism (11), promoting holoprotein assembly from newly expressed α and β chains in immature red blood cells or reticulocytes. This prediction seems to fit with previous observations by Spirin’s group (103), which suggest cotranslational heme binding to nascent globin chains coming off the ribosome in cell-free lysates of rabbit reticulocytes. Alternatively, at much lower concentrations of Hb subunits and free heme, hemin binding during assembly will proceed through conformational selection (11) of partially or fully folded conformations (Fig. 7, C and D). Even though the total amount of holoHb being generated during erythropoiesis is large, the absolute concentrations of the newly synthesized apo chains and free hemin in the steady state are likely to be low because of rapid Hb assembly and hemin sequestering in membranes and carrier proteins (104). In addition, if unfolded globin chains and free hemin were present at high concentrations, they would self-aggregate rapidly to form protein precipitates and stacked hemin complexes (75), which would compete with assembly, causing unwanted pathological situations.

We do acknowledge that our disassembly model derived from in vitro studies cannot completely capture in vivo disassembly and assembly mechanisms. Within packed red cells, nonspecific or quinary interactions (105,106) will occur between different combinations of α and β chains for the formation of transient U2 species (Fig. 7 B; (10)). Our previous in vitro experiments have shown that transient aggregation to generate apo-U2 intermediates dampens dimer formation (10). Although these interactions could facilitate the correct orientations for heterodimer assembly, such nonspecific interactions could also potentially lead to inclusion bodies in red cells. The latter is especially likely if the subunit concentrations are unequal and result in homo-oligomers (e.g., αn or βn occurring during thalassemia diseases) because of disrupted expression or genetic instability of either α or β subunits (26). In vivo experiments are needed to investigate how these nonspecific interactions and molecular crowding influence the α1β1 dimer formation during Hb biosynthesis.

When initially discovered, AHSP was suggested to be a chaperone that could facilitate Hb formation by stabilizing α subunits in a folded conformation (107,108). However, more recent work suggests that AHSP acts to stabilize and mitigate the toxicity of excess α chains by preventing the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through hemichrome formation and facilitating reduction and reassembly with β subunits (53,109,110). In in vitro assays, AHSP actually competes with folded β chains for interaction with intact α chains and, at high concentrations, inhibits hemoglobin assembly (53,110).

Finally, hemichromes are often observed within inclusion or Heinz bodies in red cells (18,23). These particulates are found in red cells for hemoglobinopathies associated with globin instability or oxidative stress. The results in Fig. 7, A and B provide an explanation for the presence of these species. At the high internal hemoglobin concentration in red cells, the unfolded holoprotein intermediates are dominant, leading to a much higher probability of misassembled Hb being trapped in the large hemichrome populations associated with the UH or IH2 states.

Our model was developed to examine unfolding as a function of GdnHCl denaturant concentrations but could be modified to include other environmental or physiological Hb disassembly triggers such as low pH or high temperatures. Additionally, we can use the population fraction values extrapolated to 0 M GdnHCl to estimate the relative absolute free energies of different folding species in vivo. These relative free energies are defined as −RTlnYi for species i, where a large positive value indicates a very unstable state (Fig. 9; Table S2). This value estimates the amount of free energy that has to be added to disassemble or unfold the globin to a particular state. Fig. 9 and Table S2 show that the free-energy differences between apo- and holointermediates are predicted to be higher in red cells compared with dilute plasma environments where hemin and subunit dissociation is promoted. However, in both environments, the holo and semi-holo disassembly intermediates are generally favored over the apoglobin variants.

Figure 9.

Predicted relative free energies of various HbA disassembly intermediates (A) in red cells and (B) diluted into plasma. The calculations of the mean values (represented by the bar chart) and standard deviations (represented by the error bars) of the relative free energies are explained in detail in the third section of the Supporting Materials and Methods. To see this figure in color, go online.

Additionally, our equilibrium constants were derived at 10°C instead of at the human body temperature of 37°C because of the experimental complexity of maintaining the integrity of the disassembly intermediates. To thoroughly examine the temperature dependence of the free-energy changes of disassembly reactions, further experimental studies need to be pursued at varying temperatures to derive the enthalpy of the processes. With increasing temperature, the disassembly mechanism will favor hemin loss and Hb disassembly steps. However, we believe our model does provide a physiologically relevant description of the dependence on protein or heme concentration. The model predicts that 1) unstable apoglobins are less favored relative to holo variants and 2) tetrameric Hb dominates at the remarkably high protein concentration found in red cells ([Hb] ≈ 20,000 μM compared with K4,2 ≈ 2–10 μM).

When not contained within the reductive environment of red cells, acellular Hb in plasma undergoes rapid autoxidation, forming metHb, which in turn enables rapid heme disassociation. NO, which is generated in endothelial cells to facilitate vasodilation, can also react rapidly with acellular oxyHb to produce metHb and nitrate. A surge of acellular Hb in the bloodstream can lead to vasoconstriction due to NO scavenging by this dioxygenation reaction and subsequent release of hemin from acellular metHbA (91,111, 112, 113, 114, 115).

The early onset of a significant population of disassociated free hemin in the low protein concentration pathway (Fig. 7, C and D) provides an explanation for why chronic or severe hemolysis triggers free-hemin-mediated inflammatory diseases and endothelial dysfunctions that lead to serious cardiovascular complications and kidney problems (89,116,117). The disassociated free hemin intercalates into cell membranes and leads to the generation of ROS that can damage lipid, protein, and DNA (111,118). Free hemin can also bind specifically to the toll-like receptor-4 on endothelial cells, triggering adverse proinflammatory cell cascades (119,120). Hemin-mediated ROS generation and oxidative stress on the blood vessel walls also promote adhesion molecule expression on the walls, leading to platelet aggregation and thrombosis (89,111).

Conclusion

We have been able to propose—for the first time, to our knowledge—a reasonable quantitative Hb disassembly and assembly model (see Fig. 2 and final parameters in Table 1), which can be used as a framework to identify the factors that resist Hb denaturation and those that enhance expression. The key feature of our model involves formation of molten globule intermediates with hemichrome spectral properties, and these intermediates are part of the pathway for the disassembly and unfolding of native hemoglobin. Complementary computational studies are also being done in our group to expand this framework to include interpretations at an atomic level. Hopefully, our efforts to obtain a comprehensive mechanism of Hb disassembly will lead to strategies for addressing erythropoiesis disorders and hemoglobinopathies in a clinical setting and for engineering more stable acellular hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers for transfusion therapy and other commercial purposes.

Author Contributions