Abstract

Background:

Patients treated with hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) often experience depression and fatigue but analyses to determine risk factors have typically lacked statistical power. This study examined sociodemographic and clinical risk factors for depression and fatigue in a large cohort of HCT survivors.

Methods:

Measures of depression and fatigue were included in an annual survey of HCT recipients which also included self-reported sociodemographic and health information. Patient clinical characteristics were obtained from the clinical database.

Results:

The sample consisted of 1869 recipients (mean age 56, 53% male) who were a mean of 13 years (allogeneic recipients) and 6 years (autologous patients) since HCT. Moderate to severe depression was reported by 13% of participants; moderate to severe fatigue was reported by 42%. Among allogeneic recipients, female gender, younger age, current presence of chronic pain, and current patient-reported severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) were independently associated with greater depression whereas female gender, current presence of chronic pain, and current severity of chronic GVHD were independently associated with greater fatigue (p values<.01). Among autologous recipients, younger age and current presence of chronic pain were independently associated with both greater depression and greater fatigue (p values<.01).

Conclusions:

Rates of depression and fatigue in this group of survivors suggest a high symptom burden. Better screening, referral, and interventions are needed.

Condensed abstract:

This study examined sociodemographic and clinical risk factors for depression and fatigue in a large cohort of hematopoietic cell transplant survivors. Several risk factors were independently associated with depression and fatigue, including gender, age, current severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease, and current presence of chronic pain.

Background

Depression and fatigue are two of the most common symptoms reported by patients during and after hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT).1 Previous studies have reported that 6–16% of HCT recipients experience clinically significant depression before transplant, 31–38% during hospitalization, and 11% during long-term survivorship.2–5 Clinically-significant fatigue has been reported by 95% of patients before HCT,6 81% at day 100 after HCT,7 and has been found to remain significantly elevated among long-term survivors relative to the general population.8

Not only are depression and fatigue distressing to patients, they are also associated with adverse outcomes. Depression is associated with non-adherence to the post-HCT regimen,9 increased hospital length of stay,10 and greater mortality.10, 11 Suicidal ideation is 13 times more likely in HCT recipients with depression than recipients without depression.5 A study of older adults with myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia showed that fatigue prospectively predicted reduced survival.12 These data raise the possibility that early identification and proactive management of patients at risk of depression and fatigue may help to improve outcomes after HCT.

Early identification of patients at risk has been hampered by inconsistent findings regarding risk factors for depression and fatigue among HCT recipients. Sociodemographic and clinical factors such as younger age, lower socioeconomic status, and presence of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) have been found to be associated with depression, but findings are inconsistent.2, 5, 13 Similarly, female gender and GVHD have been inconsistently associated with fatigue.14, 15 Mixed findings may reflect methodological limitations such as small sample size which reduces statistical power, heterogeneous samples of allogeneic and autologous patients, and the use of single-item measures of depression and fatigue embedded into quality of life questionnaires as opposed to multi-item scales.

The current study was designed to examine sociodemographic and clinical risk factors of depression and fatigue in a large sample of HCT survivors surveyed through the annual Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) HCT survivorship survey. To address limitations of previous research, data from allogeneic and autologous survivors were analyzed separately, while depression and fatigue were assessed with the use of previously-validated multi-item measures. We hypothesized that depression and fatigue would be associated with certain sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., female gender, younger age, minority race/ethnicity), treatment variables (i.e., shorter time from transplant, unrelated donor, myeloablative regimen, receipt of mobilized peripheral blood allogeneic stem cells, higher total body irradiation dose), post-transplant complications (i.e., greater length of hospital stay, longer time to engraftment, the current presence of chronic pain, greater current severity of chronic GVHD, maximum mucositis score, disease relapse after HCT, second malignancy after HCT), and putative inflammation [i.e., positive patient and donor cytomegalovirus (CMV) status].

Methods

Participants

Patients (or parents or guardians of minors) who had a HCT at the FHCRC or the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (FHCRC/SCCA) are mailed an annual survivorship survey to evaluate their self-reported health status. After approval by the FHCRC Institutional Review Board, measures of depression and fatigue were included in surveys mailed between July 1, 2012 and June 30, 2013 to all consenting survivors who were at least 18 years of age. Surveys were mailed once with a self-addressed stamped return envelope. Patients who had not returned their completed surveys within one month were sent a reminder letter. Completed surveys were accepted through October 31, 2013.

Measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8)16 was used to assess depressive symptoms during the previous two weeks. Items correspond to the criteria required for a DSM-IV diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Items are evaluated on a four-point Likert scale (0=not at all, 3=nearly every day) and responses are summed to produce a total score. Scores of 10 or above indicate moderate to severe depression.16 The PHQ-8 has previously been used to measure depression in cancer survivors.17 The Fatigue Symptom Inventory (FSI)18 was used to measure fatigue severity during the preceding week. The FSI is a 14-item scale that assesses the frequency, severity, and disruptiveness of fatigue. Fatigue severity is represented by the average of 4 items assessing the most, least, average, and current level of fatigue experienced according to an 11-point Likert scale (0 = not at all fatigued; 10 = as fatigued as I could be). Scores of 4 or above indicate moderate to severe fatigue.19 Previous research has demonstrated the reliability and validity of the FSI with individuals diagnosed with cancer.20 The survey collected self-reported health information including current severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease (chronic GVHD) (none, mild, moderate, severe) and current chronic pain (yes/no). Additional sociodemographic and clinical variables were extracted from the FHCRC database, including patient gender, age, transplant type, time since transplant, race, ethnicity, disease type and status, donor type, HLA match/mismatch, graft source, myeloablative conditioning, patient and donor CMV serum status, length of hospital stay, time to neutrophil engraftment, maximum mucositis score, disease relapse after HCT, and development of a second malignancy after HCT.

Statistical Analyses

Depression and fatigue were analyzed as continuous variables. Univariate associations with sociodemographic and clinical variables were examined using Pearson correlations and independent samples t-tests. As a partial adjustment for multiple comparisons, p values less than .01 were considered statistically significant. To evaluate the independent contributions of sociodemographic and clinical variables to depression and fatigue, multivariable linear regression analyses were conducted including all variables meeting the criterion for statistical significance in univariate analyses. Analyses were conducted separately for allogeneic and autologous HCT recipients. To further characterize the clinical significance of findings, univariate logistic regressions were conducted to examine the odds of reporting moderate to severe depression or fatigue given the presence of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. To limit the number of comparisons, logistic regressions were conducted only for characteristics found to be significantly associated (i.e., p<.01) in univariate analyses with depression and fatigue measured as continuous outcomes. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

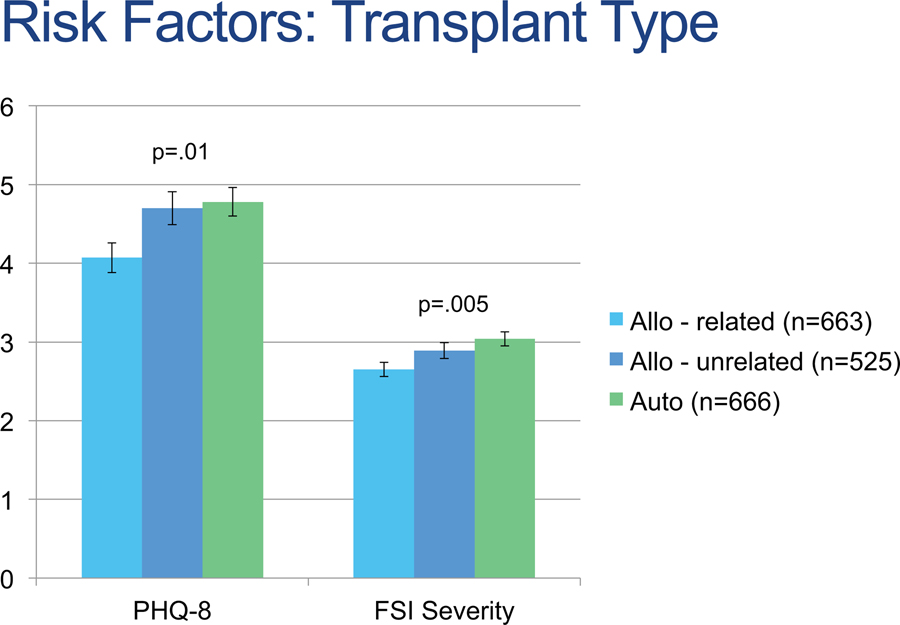

Surveys were mailed to 4,740 patients and 1,907 (40%) responded. Responders were more likely to: be female, be white, be non-Hispanic, have more recent HCT, have received autologous HCT, have received mobilized peripheral blood stem cells, and have received non-myeloablative conditioning (p values<.01). Thirty-eight patients did not provide complete data regarding fatigue and depression, resulting in a sample of 1,869 patients who contributed data to the current analyses. Sample demographic and clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1. Rates of moderate to severe depression and fatigue were higher in autologous survivors as compared to allogeneic survivors with a related donor (p<.05), while allogeneic survivors with an unrelated donor did not show statistically significant differences with either group (p values>.05) (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample (N=1,869).

| Allogeneic (n=1,188) | Autologous (n=666) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender: Male, n (%) | 617 (52) | 365 (55) |

| Age: years, median (range) | 56 (18–81) | 62 (18–83) |

| Race: Caucasian, n (%) | 1092 (92) | 601 (90) |

| Ethnicity: non-Hispanic, n (%) | 1143 (96) | 636 (96) |

| Years since transplant: mean (SD) | 13 (0–40) | 6 (0–32) |

| Diagnosis at transplant | ||

| Acute leukemia | 27 (4) | 433 (36) |

| Aplastic anemia | 0 (0) | 64 (5) |

| Autoimmune disease | 9 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Chronic leukemia | 3 (<1) | 330 (28) |

| Hodgkin’s disease | 59 (9) | 21 (2) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 0 (0) | 121 (10) |

| Myeloma | 260 (39) | 46 (4) |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasm | 0 (0) | 56 (5) |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 233 (35) | 89 (7) |

| Solid tumor | 37 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 24 (4) | 21 (2) |

| Missing | 14 (2) | 7 (1) |

| Disease status number at transplant, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 29 (2) | 49 (7) |

| 1 | 315 (27) | 144 (22) |

| 2 | 113 (10) | 33 (5) |

| 3 | 20 (2) | 6 (1) |

| 4 | 2 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 709 (60) | 434 (65) |

| CMV serum positive status pretransplant, n (%) | ||

| Patient | 533 (47) | 320 (48) |

| Donor | 433 (36) | |

| Graft source: n (%) | ||

| Mobilized peripheral blood stem cells | 549 (46) | 622 (93) |

| Bone marrow | 606 (51) | 38 (6) |

| Umbilical cord blood | 32 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Bone marrow/peripheral blood stem cells | 1 (<1) | 6 (1) |

| Donor type: n (%) | ||

| Related | 663 (56) | |

| Unrelated | 525 (44) | |

| Donor age: mean years (SD) | 37 (14) | |

| Myeloablative conditioning: n (%) | 242 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Days to engraftment: median (range) | 11 (2–94) | 14 (7–77) |

| Length of hospital stay: median days (range) | 27 (0–197) | 0 (0–125) |

| Disease relapse after HCT: Yes, n (%) | 137 (12) | 77 (12) |

| Second malignancy after HCT: Yes, n (%) | 392 (33) | 122 (18) |

| Current chronic pain: Yes, n (%) | 286 (24) | 209 (31) |

Figure 1.

Depression and fatigue scores by transplant type. Allo indicates allogeneic; auto, autologous; FSI, Fatigue Symptom Inventory; PHQ‐8, Patient Health Questionnaire‐8.

Among allogeneic survivors, 14% of the sample met criteria for moderate to severe depression, 31% met criteria for moderate to severe fatigue, and 12% of the sample met criteria for both. Depression and fatigue were significantly correlated (r=.73, p<.0001). As shown in Table 2, univariate analyses indicated that depression was higher among women (p=.003), younger survivors (p=.007), those with greater severity of current chronic GVHD (p<.0001), and those with chronic pain (p<.0001). Fatigue was significantly higher among women (p=.0002) as well as survivors transplanted more recently (p=.0005), with greater severity of current chronic GVHD severity (p<.0001), and with current chronic pain (p<.0001). Table 3 displays the results of multivariable regression. Sociodemographic and clinical variables predicted 19% of variance in depression scores; gender (p=.005), age (p=.002), current severity of chronic GVHD (p<.0001), and current presence of chronic pain (p<.0001) were independent predictors. Logistic regression indicated that the odds of reporting moderate to severe depression were greater among survivors with more severe current chronic GVHD (OR=1.90, 99% CI=1.47–2.46), and survivors with current chronic pain (OR=5.06, 99% CI=3.21–7.99) but did not significantly differ by age (OR=.99, 99% CI=.98–1.01) or gender (OR=1.48, 99% CI=.95–2.29). Sociodemographic and clinical variables accounted for 17% of the variance in fatigue; independent predictors were gender (p<.0001), current severity of chronic GVHD (p<.0001), and presence of current chronic pain (p<.0001) but not time from transplant (p=.027). Logistic regression indicated that the odds of reporting moderate to severe fatigue were greater among women (OR=1.42, 99% CI=1.03–1.96), survivors with more severe current chronic GVHD (OR=1.77, 99% CI=1.42–2.21), and survivors with chronic pain (OR=5.67, 99% CI=3.90–8.25) but were not associated with time from transplant (OR=.98, 99% CI=.96–1.00).

Table 2.

Univariate associations of demographic and clinical characteristics with depression and fatigue.

| Depression | Fatigue | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allogeneic | Autologous | Allogeneic | Autologous | |||||||||

| Gender | Female: 4.78 (4.99) | Male: 3.95 (4.54) | p=.003 | Female: 5.32 (4.63) | Male: 4.33 (4.68) | p=.006 | Female: 3.00 (2.26) | Male: 2.52 (2.15) | p=.0002 | Female: 3.22 (2.22) | Male: 2.89 (2.14) | p=.053 |

| Age | r=−.08, p=.007 | r=−.20, p<.0001 | r=−.04, p=.14 | r=−.13, p<.0001 | ||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | White non-Hispanic: 4.34 (4.76) | Minority: 4.51 (4.95) | p=.72 | White non-Hispanic: 4.72 (4.61) | Minority: 5.34 (5.21) | p=.29 | White non-Hispanic: 2.75 (2.22) | Minority: 2.79 (2.21) | p=.85 | White non-Hispanic: 2.97 (2.17) | Minority: 3.61 (2.27) | p=.021 |

| Time since transplant | r=−.06, p=.06 | r=−.04, p=.27 | r=−.10, p=.0005 | r=−.02, p=.58 | ||||||||

| Disease status number | r=.06, p=.17 | r=.09, p=.19 | r=.08, p=.08 | r=.09, p=.16 | ||||||||

| TBI dose | r=.02, p=.55 | r=.05, p=.23 | r=−.00, p=.88 | r=.04, p=.29 | ||||||||

| Donor type | Related: 4.08 (4.78) | Unrelated: 4.70 (4.76) | p=.027 | Related: 10.61 (8.92) | Unrelated: 11.56 (8.78) | p=.07 | ||||||

| Patient CMV status | Positive: 4.54 (4.91) | Negative: 4.12 (4.64) | p=.14 | Positive: 4.83 (4.74) | Negative: 4.58 (4.57) | p=.51 | Positive: 2.84 (2.25) | Negative: 2.67 (2.17) | p=.20 | Positive: 2.98 (2.20) | Negative: 3.02 (2.12) | p=.82 |

| Donor CMV status: | Positive: 4.41 (4.78) | Negative: 4.36 (4.68) | p=.62 | Positive: 2.86 (2.27) | Negative: 2.69 (2.16) | p=.21 | ||||||

| Myeloablative therapy | Yes: 4.69 (4.65) | No: 4.25 (4.80) | p=.21 | Yes: 2.99 (3.27) | No: 2.68 (2.20) | p=.06 | ||||||

| Graft source* | PBSC: 4.53 (4.66) | BM: 4.14 (4.83) | p=.16 | PBSC: 4.78 (4.72) | BM: 4.78 (4.29) | p=.99 | PBSC: 2.93 (2.19) | BM: 2.61 (2.22) | p=.014 | PBSC: 3.04 (2.87) | BM: 2.89 (2.19) | p=.69 |

| Time to engraftment | r=−.02, p=.48 | r=.09, p=.020 | r=−.05, p=.12 | r=.08, p=.07 | ||||||||

| Length of hospital stay | r=−.04, p=.17 | r=.08, p=.039 | r=−.04, p=.14 | r=.05, p=.22 | ||||||||

| Maximum mucositis score | r=−.01, p=.80 | r=.06, p=.20 | r=−.01, p=.84 | r=.01, p=.85 | ||||||||

| Disease relapse | Yes: 4.45 (4.89) | No: 4.34 (4.77) | p=.80 | Yes: 4.95 (4.82) | No: 4.76 (4.67) | p=.74 | Yes: 3.10 (2.46) | No: 2.71 (2.18) | p=.08 | Yes: 3.25 (2.09) | No: 3.01 (2.20) | p=.37 |

| Second malignancy | Yes: 4.05 (4.68) | No: 4.50 (4.82) | p=.12 | Yes: 4.16 (4.05) | No: 4.92 (4.80) | p=.07 | Yes: 2.55 (2.19) | No: 2.86 (2.22) | p=.022 | Yes: 2.95 (2.15) | No: 3.06 (2.20) | p=.63 |

| Current chronic GVHD severity | r=.25, p<.0001 | r=.24, p<.0001 | ||||||||||

| Current chronic pain | Yes: 7.39 (5.50) | No: 3.23 (3.90) | p<.0001 | Yes: 6.77 (5.48) | No: 3.77 (3.89) | p<.0001 | Yes: 4.22 (2.14) | No: 2.22 (1.99) | p<.0001 | Yes: 4.02 (2.06) | No: 2.53 (2.33) | p<.0001 |

Note: BM: bone marrow, CMV: cytomegalovirus, GVHD: graft-versus-host disease, PBSC: mobilized peripheral blood stem cells, TBI: total body irradiation

Only patients receiving PBSC or BM were included in analyses due to small number of patients who received cord blood or BM/PBSC.

Table 3.

Multivariable analyses predicting fatigue and depression from sociodemographic and clinical variables.

| Outcome: Depression among allogeneic recipients | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted Beta | p |

| Gender = Female | 0.71 | .005 |

| Age | −0.03 | .002 |

| Current chronic GVHD severity | 3.65 | <.0001 |

| Current chronic pain | 1.09 | <.0001 |

| Outcome: Fatigue among allogeneic recipients | ||

| Gender = Female | 0.47 | <.0001 |

| Time from transplant | −0.01 | .027 |

| Current chronic GVHD severity | 1.77 | <.0001 |

| Current chronic pain | 0.43 | <.0001 |

| Outcome: Depression among autologous recipients | ||

| Gender = Female | 0.73 | .034 |

| Age | −0.08 | <.0001 |

| Current chronic pain | 2.90 | <.0001 |

| Outcome: Fatigue among autologous recipients | ||

| Age | −0.03 | .0002 |

| Current chronic pain | 1.43 | <.0001 |

Among autologous survivors, 15% of the sample met criteria for moderate to severe depression, 31% met criteria for moderate to severe fatigue, and 12% met criteria for both, essentially the same proportions as seen in allogeneic survivors. Depression and fatigue were significantly correlated (r=.73, p<.0001). Univariate analyses indicated that depression was significantly higher among women (p=.006), younger survivors (p<.0001), and survivors with current chronic pain (p<.0001), while fatigue was higher among younger survivors (p<.0001) and those with current chronic pain (p<.0001). Multivariable analysis indicated that sociodemographic and clinical variables predicted 13% of variance in depression scores; age (p<.0001) and current chronic pain (p<.0001) but not gender (p=.034) were independent predictors. Logistic regression indicated that the odds of reporting moderate to severe depression were decreased with age (OR=.97, 99% CI=.95-.99) and were increased among survivors with chronic pain (OR=3.11, 99% CI=1.73–5.58) but were not associated with gender (OR=1.53, 99% CI=.86–2.72). Eleven percent of variance in fatigue was predicted by sociodemographic and clinical variables; age (p=.0002) and current chronic pain (p<.0001) were independent predictors. Logistic regression indicated that the odds of reporting moderate to severe fatigue were increased among survivors with chronic pain (OR=3.03, 99% CI=1.92–4.75) and decreased with age (OR=.98, 99% CI=.96-.99).

Conclusions

The current study examined risk factors for depression and fatigue in a large sample of autologous and allogeneic HCT recipients who provided data via the annual FHCRC survivorship survey. Among allogeneic HCT survivors, independent risk factors for depression were female gender, younger age, current severity of chronic GVHD, and current chronic pain. Risk factors for fatigue were female gender, current severity of chronic GVHD, and current chronic pain. Among autologous HCT survivors, independent risk factors for both depression and fatigue were younger age and current chronic pain. These data are significant because they result from one of the first well-powered studies to examine sociodemographic and clinical risk factors of depression and fatigue after HCT. These common and distressing symptoms are associated with adverse outcomes including reduced quality of life and shortened survival.3, 21

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend screening for distress and fatigue at regular intervals in all patients.19, 22 The high prevalence of depression and fatigue in HCT recipients in the current study underscores these recommendations. Relationships among depression, fatigue, and chronic pain observed in the current study are consistent with those reported previously in cancer patients23 and suggest that multimodal treatment may be necessary to manage symptomatology in these patients. Treatment of one symptom may improve others. For example, medication may be required for pain, which may in turn ease depression and fatigue. Treatment with anti-depressants may need to be initiated or adjusted. Supervised exercise can improve fatigue in HCT recipients.24, 25 Cognitive behavioral therapy may assist with lifestyle changes and may improve depression and fatigue as well.26, 27 The self-reported instruments used to measure depression and fatigue were 22 items total, but a smaller number of items can be used for screening for depression and fatigue in a clinical setting. For depression, the Patient Health Questionniare-2 (PHQ-2) can be used.28 It consists of two items asking patients whether they have had “little interest or pleasure in doing things” or have been “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless” during the previous two weeks (0=not at all, 1=several days, 2=more than half the days, 3=nearly every day). A total score of three or greater indicates that further evaluation of depression is warranted.28 For fatigue, a single item has been recommended for screening.29 The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS)30 tiredness item asks patients to assess their current degree of tiredness on an 11-point scale (0=no tiredness, 10=worst possible tiredness); the cutoff for clinical significance is a score of 4 or greater.29

Results from the current study help to clarify previous mixed findings regarding risk factors for depression and fatigue. Previous studies in HCT have found male gender to be associated with greater depression5 or no association of gender with depression.2 Our finding that female gender is a risk factor for depression and fatigue is consistent with data from non-cancer populations and cancer survivors not treated with HCT.31–33 Similarly, younger age has previously been reported as a risk factor for depression in HCT recipients32 and among cancer survivors not treated with HCT.17, 31 Chronic GVHD has previously been associated with depression and fatigue.32, 34 Chronic pain has been found to be associated with depression and fatigue in cancer survivors not treated with HCT, 35, 36 although our study is the first to our knowledge reporting a relationship in HCT recipients. The clinical significance of chronic GVHD and chronic pain is striking. Each increase in chronic GVHD severity (e.g., from mild to moderate or moderate to severe) was associated with a 90% increase in the likelihood of moderate to severe depression and a 77% increase in the likelihood of moderate to severe fatigue. The presence of chronic pain was associated with increases of over 400% in the likelihood of moderate to severe depression and fatigue in allogeneic survivors. Among autologous survivors, the presence of chronic pain was associated with increases of over 200% in moderate to severe depression and fatigue. These results suggest that patients reporting chronic GVHD or chronic pain are at particular risk of depression and fatigue.

Interestingly, most clinical variables were not risk factors for depression and fatigue. Characteristics of HCT or previous treatment, such as TBI dose, myeloablative conditioning, and graft source did not meet our criterion of statistical significance (i.e., p≤.01). Similarly, proxies for early post-HCT complications, including length of hospital stay, time to engraftment, maximum mucositis score, and late transplant complications such as disease relapse and development of second malignancy were also not associated with depression or fatigue. The large sample size reduces the likelihood that the study was underpowered to find significant effects. Instead, it appears that depression and fatigue may in part arise from circumstances other than aspects of the transplant itself (e.g., personality, coping, genetics). Although putative markers of inflammation such as prior patient and donor CMV infection were not associated with depression or fatigue, a growing body of evidence suggests that depression and fatigue in HCT recipients may in part be immune-mediated.37, 38 Thus, CMV variables could represent poor proxies for heightened immune response.

Strengths of the current study include a large and heterogeneous sample of HCT recipients and the use of well-validated measures of depression and fatigue. Nevertheless, limitations should be noted. Because the study was cross-sectional, it was not possible to include a pre-transplant assessment of depression and fatigue. Previous studies have found depression and fatigue in HCT survivors to return to pre-transplant levels on average after the acute transplant period,8, 39 thus, it is unclear the extent to which risk factors identified in the current study would remain significant if pre-HCT depression and fatigue were included in analyses. Pre-HCT depression and fatigue are not routinely measured in clinical practice and consequently may have less relevance in a risk model than the variables measured in the current study. Severity of chronic GHVD was assessed via self-report rather than chart abstraction. As patient reports can provide complementary information to clinical scoring of chronic GVHD, ideally both would be collected. It should be noted that 40% of survivors responded to the survey. Several sociodemographic and clinical differences were observed between non-responders. For example, responders were more likely to: be female, be white, be non-Hispanic, have more recent HCT, have received autologous HCT, have received mobilized peripheral blood stem cells, and have received non-myeloablative conditioning. We were unable to compare rates of depression and fatigue between responders and non-responders. Patients who were depressed and fatigued may have been less likely to complete the survey due to how they were feeling or, conversely, been more interested in completing the survey because it was asking about current concerns. Participants in the current study were transplanted at one center and were relatively homogenous in terms of race and ethnicity. For these reasons, caution should be exercised when generalizing results of the current study to the larger HCT population.

In summary, data from the current study suggest that sociodemographic factors and concomitant symptomatology, but generally not clinical factors, place HCT recipients at risk of depression and fatigue. This information can be used to guide screening decisions as well as supportive care recommendations. Psychological screening has been shown to be feasible and result in improved patient and provider satisfaction with care.40, 41 Proactive management of symptomatology may contribute to better quality of life and other outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH K07-CA138499, NIH P01-CA018029

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Mosher CE, DuHamel KN, Rini C, Corner G, Lam J, Redd WH. Quality of life concerns and depression among hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19: 1357–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artherholt SB, Hong F, Berry DL, Fann JR. Risk factors for depression in patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2014;20: 946–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Jawahri AR, Traeger LN, Kuzmuk K, et al. Quality of life and mood of patients and family caregivers during hospitalization for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2015;121: 951–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pillay B, Lee SJ, Katona L, Burney S, Avery S. Psychosocial factors associated with quality of life in allogeneic stem cell transplant patients prior to transplant. Psychooncology. 2014;23: 642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun CL, Francisco L, Baker KS, Weisdorf DJ, Forman SJ, Bhatia S. Adverse psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS). Blood. 2011;118: 4723–4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherman AC, Simonton S, Latif U, Plante TG, Anaissie EJ. Changes in quality-of-life and psychosocial adjustment among multiple myeloma patients treated with high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15: 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Marden S. The symptom experience in the first 100 days following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Support Care Cancer. 2008;16: 1243–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hjermstad MJ, Knobel H, Brinch L, et al. A prospective study of health-related quality of life, fatigue, anxiety and depression 3–5 years after stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34: 257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mumby PB, Hurley C, Samsi M, Thilges S, Parthasarathy M, Stiff PJ. Predictors of non-compliance in autologous hematopoietic SCT patients undergoing out-patient transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47: 556–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prieto JM, Blanch J, Atala J, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20: 1907–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loberiza FR Jr., Rizzo JD, Bredeson CN, et al. Association of depressive syndrome and early deaths among patients after stem-cell transplantation for malignant diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20: 2118–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deschler B, Ihorst G, Platzbecker U, et al. Parameters detected by geriatric and quality of life assessment in 195 older patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia are highly predictive for outcome. Haematologica. 2013;98: 208–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown-Iannuzzi JL, Payne BK, Rini C, DuHamel KN, Redd WH. Objective and subjective socioeconomic status and health symptoms in patients following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology. 2014;23: 740–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen MZ, Rozmus CL, Mendoza TR, et al. Symptoms and quality of life in diverse patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44: 168–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tonosaki A. The long-term effects after hematopoietic stem cell transplant on leg muscle strength, physical inactivity and fatigue. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16: 475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114: 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao G, Okoro CA, Li J, White A, Dhingra S, Li C. Current depression among adult cancer survivors: findings from the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38: 757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Azzarello LM, et al. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1998;7: 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cancer-Related Fatigue (Version 2.2015). Available from URL: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/fatigue.pdf [accessed October 12, 2015]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB. The Fatigue Symptom Inventory: a systematic review of its psychometric properties. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19: 169–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grulke N, Larbig W, Kachele H, Bailer H. Pre-transplant depression as risk factor for survival of patients undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology. 2008;17: 480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Distress Management (Version 2.2015). Available from URL: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/distress.pdf [accessed October 12, 2015].

- 23.Brown LF, Rand KL, Bigatti SM, et al. Longitudinal relationships between fatigue and depression in cancer patients with depression and/or pain. Health Psychol. 2013;32: 1199–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Persoon S, Kersten MJ, van der Weiden K, et al. Effects of exercise in patients treated with stem cell transplantation for a hematologic malignancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39: 682–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Haren IE, Timmerman H, Potting CM, Blijlevens NM, Staal JB, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Physical exercise for patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther. 2013;93: 514–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goedendorp MM, Gielissen MF, Verhagen CA, Bleijenberg G. Psychosocial interventions for reducing fatigue during cancer treatment in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009: CD006953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Hart SL, Hoyt MA, Diefenbach M, et al. Meta-analysis of efficacy of interventions for elevated depressive symptoms in adults diagnosed with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104: 990–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41: 1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howell D, Keller-Olaman S, Oliver TK, et al. A Pan-Canadian Practice Guideline: Screening, Assessment and Care of Cancer Related Fatigue in Adults with Cancer. Toronto: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (Cancer Journey Advisory Group) and the Canadian Association of Psychosocial Oncology, February, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7: 6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linden W, Vodermaier A, Mackenzie R, Greig D. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord. 2012;141: 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62: 1097–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Junghaenel DU, Christodoulou C, Lai JS, Stone AA. Demographic correlates of fatigue in the US general population: results from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) initiative. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71: 117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pallua S, Giesinger J, Oberguggenberger A, et al. Impact of GvHD on quality of life in long-term survivors of haematopoietic transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45: 1534–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.So WK, Marsh G, Ling WM, et al. The symptom cluster of fatigue, pain, anxiety, and depression and the effect on the quality of life of women receiving treatment for breast cancer: a multicenter study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36: E205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Anderson KO, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Pain, depression, and fatigue in community-dwelling adults with and without a history of cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32: 118–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang XS, Shi Q, Shah ND, et al. Inflammatory markers and development of symptom burden in patients with multiple myeloma during autologous stem cell transplantation. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20: 1366–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang XS, Shi Q, Williams LA, et al. Serum interleukin-6 predicts the development of multiple symptoms at nadir of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2008;113: 2102–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grulke N, Albani C, Bailer H. Quality of life in patients before and after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation measured with the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Core Questionnaire QLQ-C30. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47: 473–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoodin F, Zhao L, Carey J, Levine JE, Kitko C. Impact of psychological screening on routine outpatient care of hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19: 1493–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SJ, Loberiza FR, Antin JH, et al. Routine screening for psychosocial distress following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35: 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]