Key Points

No transmissions of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome appear to have occurred in Hong Kong as the result of oral healthcare procedures.

Careful adherence to universal infection control procedures especially frequent hand washing may be an explanation.

Another explanation is that patients with fever (the highest infectivity period) tend to cancel dental appointments.

When in doubt regarding a patient's SARS status, the dental appointment should be postponed for two to three weeks.

Abstract

On Thursday 27th March 2003 the decision had been made to stop all clinical teaching and all non-elective patient care at the Prince Philip Dental Hospital, the teaching hospital of the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of Hong Kong. A lethal respiratory disease of unknown aetiology was spreading through the community but also in medical hospitals where it was infecting healthcare workers with apparent ease. Infections in an apartment block called Amoy Gardens seemed to have taken place by the deadly long distance airborne transmission route. The daily numbers of new cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome were rising exponentially. Normally bustling streets and public buildings of Hong Kong had fallen silent.

The turning point is reached

No sooner had the decision to move into a defensive posture been made, than better news began to emerge. The highly disciplined city-state of Singapore, without access to any real facts regarding the causative agent had swiftly and efficiently applied the time-honoured principles of quarantine to the disease that it had received as third port of call after Hong Kong. Those measures were stopping the disease in its tracks and offering reassurance to a world slowly waking up to the situation. Quarantine will stop the spread in the most extreme cases of infectivity, including highly virulent air-borne infections, although individual freedom is an early casualty under such circumstances.

Additionally, in an exquisite virtuoso performance of scientific expertise, a team of our colleagues in the Department of Microbiology of the University of Hong Kong together with the help of experts in CDC had identified the causative organism in a matter of days after the emergence of the problem.7 Furthermore, the team had performed the very demanding intellectual task of correctly identifying a highly unlikely suspect, whilst at least two more probable red-herring candidates had been acting as much more likely contenders. The new virus was a coronavirus, a genus well known for causing the common cold. The discovery opened the way to numerous possibilities for tracing the virus, understanding its mode of action and eventually treating it efficiently. Another possibility was the creation of a vaccine in the future. Full descriptions of the current knowledge of the virus are available in the literature.1,2,3,4,5

On the ground, however, matters seemed to continue to deteriorate with the day of Wednesday, 2nd April, being a low point for the dental hospital and the dental faculty. The World Health Organisation in an unprecedented move included Hong Kong on a list of countries to which it advised restriction of travel, having already declared the city a SARS infected area on Sunday 16th March. On the same day the University of Hong Kong Health Service contacted the dental faculty office. They revealed that a confirmed atypical pneumonia case had spent short times in the dental hospital possibly on two successive days. Furthermore the visit had been made whilst the person concerned would have been infectious.

As a consequence of those incidents, the management of the faculty and dental hospital learnt three further important lessons. These were:

How to evacuate and cleanse a zone in a clinical environment where an infected atypical pneumonia SARS case has been present.

How to distinguish between a close SARS contact and a social SARS contact.

How to control the propagation of debilitating rumours during the outbreak of a newly emerging infection.

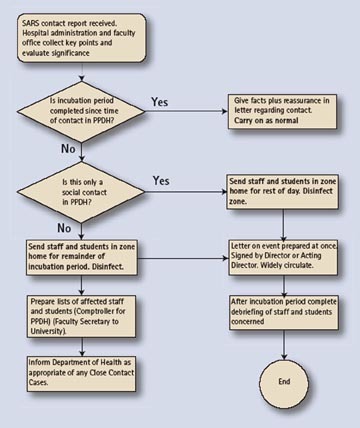

With regard to the first and second lessons, the faculty and hospital were indebted to the Director of the University Health Service who freely shared her experience of earlier incidents on the main University campus. The sequence that was followed then, and will be followed in future should further infectious SARS individuals enter the building is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Procedures after a report of an atypical pneumonia (SARS) contact

Briefly, matters took place as follows on Wednesday 2nd April. As soon as notice of the contact was received, all staff and students in the area concerned were sent home, and the area sealed off. Subsequently the area was entered by protected hospital staff that completely cleaned the area using a systematic approach following a protocol. A responsible person from another area who understands the nature of any special facilities and equipment in the area has to be assigned to advise the cleaning staff regarding their cleaning. The cleaning material of choice is a dilution of sodium hypochlorite solution in water in a ratio of 1:50. Particular attention is paid to the air conditioning system, especially the filters in the area concerned.6,7

At the same time careful enquiry was made regarding the length of time that the person had been in the building and the nature of meetings with others. Fortunately it was decided there had only been social contact and therefore the staff concerned were allowed to return next day, when they were counselled. Had the contact been a close contact then staff would have been required to remain away from work until the incubation period from the time of contact was complete. If symptoms developed during that time those concerned would have had to report to designated health centres in Hong Kong, where they would have gone to isolation facilities and tracing of their contacts would have begun. The definition of a close contact is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of atypical pneumonia (SARS) contacts

| A close atypical pneumonia (SARS) contact is a person who: |

| 1 has provided medical care for a confirmed SARS patient |

| 2 has lived with a confirmed SARS patient |

| 3 has worked for a prolonged period with a confirmed SARSpatient. |

| A social atypical pneumonia SARS contact is anyone who has been in contact with a confirmed SARS patient during the incubation and infectious periods, but who does not meet the above criteria |

By this stage it was becoming clear that a disruptive problem almost as great as the transmission itself was beginning to disrupt the organisation even whilst it was running in reduced mode. A variety of rumours, all of them discovered subsequently to be unfounded, began to sweep through the building alleging that SARS cases had occurred in members of staff, students and patients. The solution of the rumour problem was for senior management to agree to be receptive to all properly verified information and to undertake to immediately share it by means of memoranda to all areas labelled 'urgent' and 'by hand'. The arrangement for rapid dissemination of developments both good and bad was made widely known and rumours stopped thereafter.

Resumption of activities.

Whilst in late April the numbers of daily new cases remained high, and sadly deaths of those previously infected continued, the downward trend of daily new infections raised the question of when schools and universities would begin class teaching. The nature of the virus was becoming better understood and the use of that information to prevent transmissions added to the growing sense of confidence. Furthermore, by a high degree of co-operation between the health authorities and the police, contact tracing and subsequent quarantine was being carried out in a most efficient manner in Hong Kong.

It was realised that in addition to following any University decision to resume class teaching, a parallel decision would have to be made with respect to the resumption of the clinical teaching of dental students and other student members of the dental team. To prepare for that moment two written protocols were designed and widely circulated. The first gave guidance for class teaching. Advice included that group activities should be kept to a necessary minimum, students with symptoms should remain away and that everyone when in groups would wear masks. Similar strict guidance was given in the second protocol which was for treatment of patients. Again it was suggested that this was kept to the necessary minimum for the educational requirements of students. A centrepiece of this protocol was emphasis on careful history taking at every visit and encouragement to immediately dismiss patients for two weeks should any suspicion fall upon a patient.

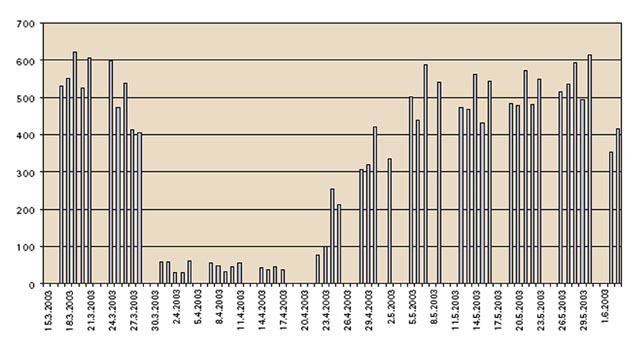

Class teaching resumed on the 14th April with clinical teaching involving treatment of patients following later. The first students to begin treatment of patients were postgraduate students and final year undergraduate students. That took place on Thursday 24th of April. Thereafter less experienced students also resumed care of patients. The final activities to resume as normal were the treatment of children. As Figure 2 shows the daily patient attendances rose remarkably quickly with nearly normal numbers being apparent after ten days. On 24th of May, to muted celebrations in Hong Kong the WHO unexpectedly lifted its negative travel advice regarding Hong Kong. In the period from the first transmissions in the Metropole Hotel, to that moment more than 13,000 dental attendances had taken place in the dental hospital, almost all of them interventionist and either carried out or observed by students. No transmissions of the disease took place however because of these dental care activities.

Figure 2.

Daily total patient attendances at the Prince Philip Dental Hospital (Reproduced from Smales F C, Samaranyake L P. Br Dent J 2003; 195 10: 557–561.)

Conclusions

Retrospectively it seems that no transmissions took place in Hong Kong during dental care. In part that might have been because many dentists closed at the early signs of the atypical pneumonia problem, and subsequently patients themselves chose to stay away in large numbers. However that cannot be the whole explanation. The most likely additional one is that the conditions for SARS transmission are quite specific and do not occur in the dental environment when the dental team are taking the normal precautions with respect to blood-borne viruses. Another is that patients would not go to the dentist when they had a high fever, and it turns out that patients are not very infective prior to the appearance of that symptom in the sequence of events during incubation of the disease.

An important feature of SARS is that it is an acute condition with a predictable course. That allowed a first rate preventative strategy for dentists which was simply, if in doubt to postpone the treatment for 14 days. That is in contra-distinction to the persistent natures of HIV and the hepatitis virus. Careful history taking will support that preventative strategy, as does the use of a clinical thermometer. An abnormally elevated temperature is a clear indication for postponement of dental treatment for the patient concerned if there is even the suspicion of prevalence of atypical pneumonia in the community.

As noted at the beginning of this article, a review of infection control procedures in the dental surgery is merited to determine the extent to which they can be optimised to minimise the effects of an as yet un-emerged new infections. However the precautions have to be reasonable and affordable otherwise they will not be practical. The worst possible emergent disease case is presumably characterised by a chronic asymptomatic carrier of an airborne lethal disease. If our experts can devise a system to prevent that form of infection then presumably everything else imaginable will be dealt with also.

However should that not be the case, then in that and possible other cases the whole world, including members of the dental team, will be relying on the combined arrangements of international surveillance, early notification and high compliance with quarantine measures to prevent a global catastrophe. It is salutatory to reflect that all of these processes have been vastly improved as result of the recent outbreak of SARS atypical pneumonia.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all staff and students of the Faculty of Dentistry, the University of Hong Kong, and The Prince Philip Dental Hospital, Hong Kong who contributed directly or indirectly to the contents of this article. Through their efforts the entire complement of the two organizations and all patients came safely through the crisis.

References

- 1.Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL, et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouchier RA, Kuiken T, Schutten M, et al. Aetiology: Koch's postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature. 2003;423:240. doi: 10.1038/423240a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes KV. SARS-associated coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1948–1951. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp030078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Centre for Infectious Disease. Basic information about SARS. Atlanta: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. May 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/factsheet.htm Last retrieval on 4th June 2003.

- 7.Li RWK, Leung KWC, Sun FCS, Samaranayake LP . Severe acute respiratory syndrome and the general practitioner Br Dent J (In press).