The novel contagious primary atypical pneumonia epidemic, which broke out in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, is now formally called Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), with the causative virus named as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).1,2 Recent studies have shown that in addition to dyspnea, hypoxemia, and acute respiratory distress, lymphopenia, and cytokine release syndrome are also important clinical features in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.3 This suggests that homeostasis of the immune system plays an important role in the development of COVID-19 pneumonia.

To provide direct evidence on leukocyte homeostasis, we studied the immunological characteristics of peripheral blood leukocytes from 16 patients admitted to the Yunnan Provincial Hospital of Infectious Diseases, Kunming, China. Among them, 10 were mild cases, 6 were severe cases; 7 were ≥50 years old, 11 were younger; and 6 had baseline diabetes, hypertension, or coronary atherosclerosis (Supplementary Table S1). Similar to the healthy group (n = 6), the absolute numbers of cells of major leukocyte subsets in peripheral blood remained at a normal level in both mild and severe patients. Different from that reported by Chen et al.,4 we did not observe increased neutrophils or decreased lymphocytes. Instead, we found that the severe group had a significant reduction in granulocytes compared to the mild group (Fig. 1a). It has been reported that elevated inflammatory mediators play a crucial role in fatal pneumonia caused by pathogenic human coronaviruses such as SARS and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome).5 We therefore examined whether inflammatory mediators can impact progression in COVID-19 patients. However, no statistical differences in interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) plasma concentrations were found among the three groups. Although patients had higher sCD14 levels than healthy people, there were no significant differences between the severe and mild groups (Fig. 1b).

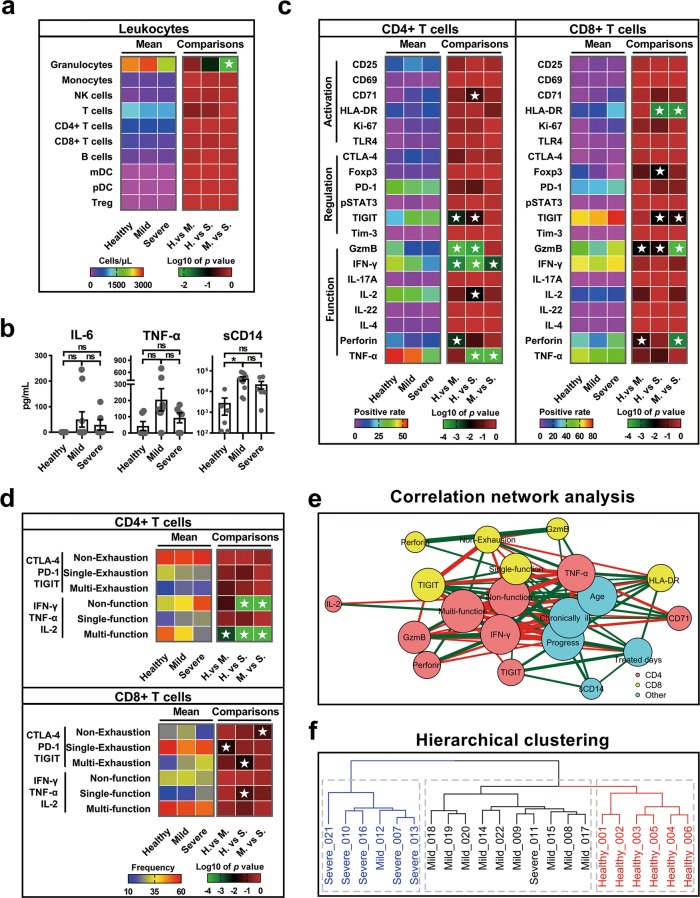

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 patients, especially those with severe infection, showed increased levels of regulatory molecules and decreased levels of multiple cytokines in peripheral blood T cells. a Heat maps comparing peripheral blood leukocyte subset concentrations in healthy (n = 6), mild (n = 10), and severe (n = 6) patients. Rainbow-colored squares represent mean values of each group. Red-black-green squares represent log 10 P values, and white asterisk indicates P ≤ 0.05 by post hoc ANOVA test. H, healthy; M, mild; S, severe. b Comparisons of IL-6, TNF-α, and sCD14 plasma concentrations in healthy, mild, and severe groups. n.s., P > 0.05, *, P ≤ 0.05, by Kruskal–Wallis test. c Comparisons of expression levels of activation-, regulation-, and function-related molecules in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells among groups. Rainbow-colored squares represent mean positive cell rate for each group. d Comparisons of cell expression modules of exhaustion-related (CTLA-4, PD-1, and TIGIT) and function-related (IFN-γ, TNFα, and IL-2) molecules in CD4+ or CD8+ T cells among groups. “Single” indicates that cell only expresses one of the three molecules, “Multi” indicates that cell expresses at least two of the three molecules, “Non” indicates that cell expresses none of the three molecules. Red-yellow-blue squares indicate average cell expression rates of different modules of three groups, respectively. e Correlation network analysis of markers with significant differences among groups. Nodes are colored based on cell type for three groups. Node size indicates relative strength value according to centrality analysis. Thicker lines indicate more correlated genes. Green lines represent significantly positive Spearman’s correlation coefficients ≥0.40; red lines represent significantly negative Spearman’s correlation coefficients ≤−0.40. f Hierarchical clustering of participants based on all immunological risk indicators

Virus-induced inflammatory factor storms can cause a systemic T cell response, reflected as changes in the differentiation and activity of T cells.6 Here, as significant differences in virus-induced inflammatory cytokines were not detected, we next examined whether homeostasis was perturbed in T cells at the cellular level (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Fig. S1). As shown in Fig. 1c, the proportions of multiple molecules related to T cell activation and regulation increased significantly in patients compared to healthy controls, but several functional molecules showed a marked decrease. Among the differentially expressed functional molecules, the levels of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and TNF-α in CD4+ T cells were lower in the severe group than in the mild group, whereas the levels of granzyme B and perforin in CD8+ T cells were higher in the severe group than in the mild group. The activation molecules showed no differences in CD4+ T cells, whereas the levels of HLA-DR and TIGIT in CD8+ T cells were higher in the severe group than in the mild group (Fig. 1c). These data indicate that COVID-19, similar to some chronic infections, damages the function of CD4+ T cells and promotes excessive activation and possibly subsequent exhaustion of CD8+ T cells. Together, these perturbations of T cell subsets may eventually diminish host antiviral immunity.7

Usually a single molecule does not adequately predict disease progression. We therefore further performed cluster analysis on marker expression using data obtained from flow cytometry. Our results showed significant differences among the three subject groups in the level of exhaustion modules, including PD-1, CTLA-4, and TIGIT, and functional modules, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2 (Supplementary Figs. S2, 3). Compared with the healthy control and mild group, the frequency of multi-functional CD4+ T cells (positive for at least two cytokines) decreased significantly in the severe group, whereas the proportion of non-functional (IFN-γ−TNF-α−IL-2−) subsets increased significantly. Studies have shown that multi-functional T cells can better control human immunodeficiency virus in natural infection and are correlated with better outcomes during vaccination; thus, the functional damage of CD4+ T cells may have predisposed COVID-19 patients to severe disease.8 Li et al.9 showed that these multi-functional CD4+ T cells occur more frequently in patients with severe SARS infections than in moderate infections. This indicates that SARS-CoV-2 may possess a unique immune pathology compared to other coronaviruses. In CD8+ T cells, the frequency of the non-exhausted (PD-1−CTLA-4−TIGIT−) subset in the severe group was significantly lower than that in the other two groups (Fig. 1d). Because functional blockade of PD-1, CTLA-4, and TIGIT is beneficial for CD8+ T cells to maintain lasting antigen-specific immunity and antiviral effects,10,11 the excessive exhaustion of CD8+ T cells in severe patients may reduce their cellular immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

To gain a comprehensive view of the above measured parameters, we also performed a correlation network analysis, and identified variables significantly related to COVID-19 disease progression, including age, chronic ailment, loss of functional diversity in CD4+ T cells, and increased expression of regulatory molecules, especially TIGIT, in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1e). Subsequent hierarchical cluster analysis showed that these immunological factors could better distinguish healthy, mild, and severe patients, independent of age and chronic ailment (Fig. 1f). In conclusion, our study identified potential immunological risk factors for COVID-19 pneumonia and provided clues for its clinical treatment.

Supplementary information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The authors contributed equally: Hong-Yi Zheng, Mi Zhang

Contributor Information

Xing-Qi Dong, Email: dongxq801@126.com.

Yong-Tang Zheng, Email: zhengyt@mail.kiz.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41423-020-0401-3) contains supplementary material.

References

- 1.Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen N, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Channappanavar R, Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017;39:529–539. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moro-Garcia MA, Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Alonso-Arias R. Influence of inflammation in the irocess of T lymphocyte differentiation: proliferative, metabolic, and oxidative changes. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:339. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saeidi A, et al. T-cell exhaustion in chronic infections: reversing the state of exhaustion and reinvigorating optimal protective immune responses. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2569. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Braeckel E, et al. Polyfunctional CD4(+) T cell responses in HIV-1-infected viral controllers compared with those in healthy recipients of an adjuvanted polyprotein HIV-1 vaccine. Vaccine. 2013;31:3739–3746. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li CK, et al. T cell responses to whole SARS coronavirus in humans. J. Immunol. 2008;181:5490–5500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston RJ, et al. The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8(+) T cell effector function. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:923–937. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engeland CE, et al. CTLA-4 and PD-L1 checkpoint blockade enhances oncolytic measles virus therapy. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:1949–1959. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.