Key Points

Proper universal infection control protocols should be conscientiously followed in dental practice, subjected to regular review and periodically relaunched.

The dental profession must remain vigilant for the emergence of new and potentially damaging pathogens.

New pathogens may have characteristics that are not catered for by existing universal infection control procedures.

Good communication and trust amongst the members of the dental team are essential parts of infection control.

Abstract

During the three months from March 2003 the economically vibrant city of Hong Kong was seriously dislocated after becoming 'second port of call' of the new and potentially fatal disease, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). The uncertainties during that period had a significant impact on the provision of dental care. However the city's only dental hospital continued to function and to support the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of Hong Kong in educating dental students and other members of the dental team. At the time of writing no transmissions of the disease have been attributed to procedures associated with dental healthcare. This article chronicles the sequence of events during the outbreak from a dental perspective. It highlights information that may be useful to dental colleagues who might someday be confronted with similar outbreaks of newly emerged potentially lethal infections.

Origins of a medical crisis

The medical authorities in Hong Kong are very conscious of the possibility of the emergence of new diseases in the adjacent provinces of Mainland China. Breeding and marketing of livestock is conducted in an intensive fashion close to large population concentrations. Fear that a bird influenza virus had crossed the species barrier and was infecting humans led to thousands of chickens being slaughtered in Hong Kong in early 1998.1,2 During the last months of 2002 rumours began to circulate that the problem was recurring in Guangdong, the nearest province of the Mainland.

At that time the Faculty of Dentistry and the associated Prince Philip Dental Hospital were reflecting upon the end of a very busy year that had seen extensive celebrations in connection with their 20th Anniversary. Both the Faculty and the Dental Hospital operate on lines similar to comparable British institutions, but with many Chinese educational features incorporated. Additionally, academic influences from other major regions of the world create a truly cosmopolitan environment.

In 2003, about 250 undergraduate dental students in the 5-year Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) course were expecting to undertake intensive prescribed clinical practice and other studies with one important target being the end-of year examinations in June. About 65 taught postgraduate students and 16 dental hygiene students were working to the similar ends. Finally, 40 dental surgery assistant students and 32 dental technology students were also studying and assisting with patient care procedures so they could qualify as fully-fledged members of the dental team. Altogether 110,000 patient attendances would take place in 2003 to support that training and also extensive programmes of dental research and continuing education.

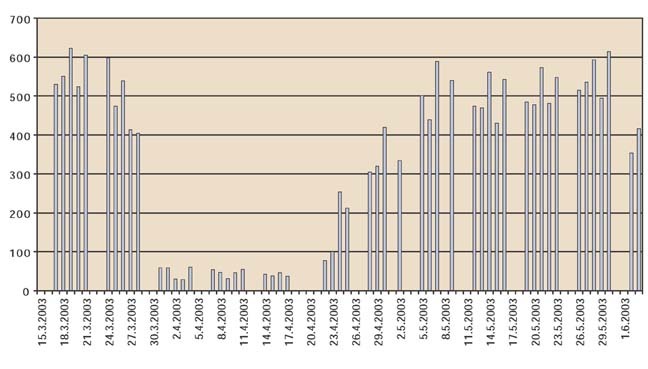

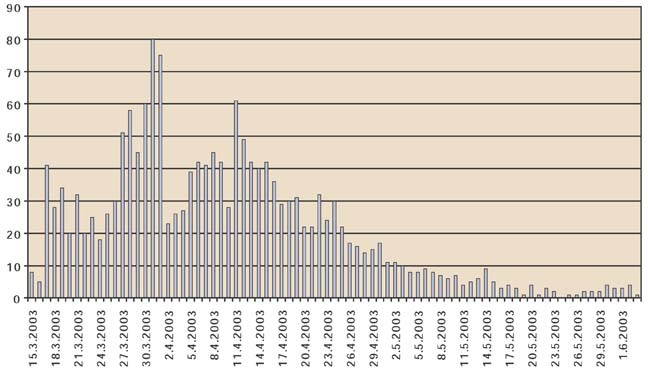

Despite the rumours from the Mainland that caused a number of worrying newspaper reports and questions to be asked in the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, the months of January and February were relatively normal in the dental hospital. Table 1 shows the patient attendances by speciality for a typical period. Nearly all the procedures would have been carried out by young people under training, or closely observed by them, thereby bringing them into contact with the patients concerned. The overall numbers of daily patient attendances throughout the crisis is shown as Figure 1. For comparison the numbers of daily newly reported cases of the disease which was about to strike Hong Kong is shown as Figure 2.

Table 1.

Patient attendances for ten working days at the end of February 2003

| Reception and primary care | 371 |

| Oral radiology | 777 |

| Oral and maxillofacial surgery | 560 |

| Emergency OMFS | 403 |

| Paediatric dentistry and orthodontics | 1,214 |

| Periodontology | 819 |

| Conservative dentistry | 783 |

| Oral rehabilitation | 567 |

| Family practice clinic | 76 |

| Total attendances | 5,570 |

Figure 1.

Daily total patient attendances at the Prince Philip Dental Hospital

Figure 2.

Daily new confirmed atypical pneumonia (SARS) cases in Hong Kong

On the 20th February a professor of respiratory medicine from the city of Guangzhou arrived in Hong Kong to attend a wedding. Feeling unwell he checked into the Metropole Hotel in Kowloon and the following day is now known to have infected at least seven other people with his condition, thereby becoming the index case of the hitherto unknown disease. In the days that followed he and two of the seven went to three different hospitals in Hong Kong where they infected substantial numbers of healthcare workers themselves setting off a cascade of other infections afterwards. Another three of the original seven contacts went to Singapore. The remaining two went to Hanoi in Vietnam, (that person arrived there on the 23rd February) and Toronto in Canada. All those who travelled abroad infected healthcare workers and others, thereby globalising the outbreak.3

In one of many twists which make the story of the outbreak stranger than the most imaginative writer of fiction could conceive, the disease was not the expected bird influenza. Surveillance for the emergence of unusual influenza outbreaks was being carefully carried out in Hong Kong. For example it was reported in the press on the 22nd February (the day of the Metropole infections) that on 16th of February a 33-year-old Hong Kong man had indeed died of bird influenza. The report shows where attention was being focused and as a result distracting awareness from the true problem.

Instead of being an influenza, the new disease was a totally new pneumonia, similar enough to resemble its common counterparts, thereby defying easy initial detection, but with two very different features soon to reveal their deadly nature. Briefly these were an extremely high level of infectivity when certain conditions were met, and a pathogenesis that included pulmonary fibrosis of an almost irreversible nature. Full description of the clinical presentation of the condition and its management are in the literature.4,5,6,7,8

Prevention in the Dental Setting

From February 21st onwards it would have been possible for one of the cases from the Metropole Hotel or the other subsequent contacts in Kowloon to attend the dental hospital for dental treatment. The hospital is only a ten minute taxi drive away from most parts of Kowloon via one of three road tunnels under the harbour of Hong Kong, the Western Tunnel. But nothing was unusually suspicious at that time to provide an alert regarding such contact patients whose numbers increased through the period. As will be seen, that situation continued until the 11th March, or for 11 full working days.

Had such a patient entered the dental hospital, they would have found that full universal infection control precautions were in place and practiced by all staff and students concerned with the treatment of patients. These measures were instituted in May 2000 after several months of careful planning by a working party including an experienced oral microbiologist (LPS). They are conducted at an extremely high level according to international norms9 and include routine use of gloves, gown and three-layer surgical masks by everyone who attends patients. These items are disposed of after every patient has been seen. The wearing of protective eye-ware is strongly recommended especially when using high speed instrumentation.9 Additional features include careful attention to cleansing all surfaces in clinical areas between patient visits and training of workmen/cleaners to carefully remove and safely dispose of clinical waste that includes all the disposable items mentioned above.

Transmission in respiratory secretions by droplets is the principal mechanism of spread of the new disease that would come to be known as SARS. Furthermore, early work has shown that the SARS virus, now termed the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) is also present in faeces, urine and possibly saliva of infectious persons. The causative agent from any of those origins is capable of persisting on surfaces. The persistence on surfaces is particularly worrying because inadvertent self-inoculation into eyes and nose after touching such contaminated surfaces seems to have been a major feature of spread in Hong Kong.10

Nevertheless, it can be suggested that despite the unsuspected features of the new disease, the universal infection control measures in the dental hospital would have prevented a transmission should a contact attended for dental care during the 11-day period. With hindsight, the routine gloving, gowning and eye-protection measures taken by all staff involved in patient treatment followed by the discarding of all items between patients would have been effective protective measures. Furthermore, careful cleaning of surfaces, strict attention to personal hygiene especially frequent hand-washing, and sealing of clinical waste before disposal would have been of equal importance.

In keeping with an approach of a critical appraisal following events however, it can be suggested it would have been better if the measure of wearing eye protection had been more forcefully emphasised. Subsequently it would be learned that tragically some healthcare workers had been infected with SARS possibly by splashes of infected secretions from patients.10

But the real lesson from this period is that the transmission nature of the deadly new disease and the arrival of the disease itself were quite unexpected. Future newly emerging diseases will probably have yet different features again. Therefore in future infection control measures in the dental surgery should be evaluated from the point of view of a wider range of possible routes of infection and pathogen behaviours. Those measures should, where possible, be optimised to meet hitherto unforeseen situations.

The period of uncertainty

Whilst the disease spread in Hong Kong, two other world cities, and Mainland China where it had originated, the returnee from the Metropole Hotel to Hanoi fell ill and was admitted to the French Hospital there on the 26th February. Professor Carlo Urbani, a World Health Organisation infectious diseases expert and president of the Italian section of Medicins sans Frontieres, was called to see the case and recognised its unusual nature.3

From then on things began to move with exceptional speed, once again contributing to the stranger-than-fiction quality of events connected with SARS. Professor Urbani had the patient isolated, instituted precautionary nursing measures, and alerted the WHO on 5th March about 'something strange and different'. WHO sent regional advisors to Hanoi on 9th of March who were closely followed by a team from the US Centres of Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. The WHO issued a global alert, and in Hong Kong where the situation in various hospitals had sadly clarified the deadly characteristics of the disease, the Hong Kong Hospital Authority announced the outbreak of a new and atypical pneumonia on March 10th. Professor Urbani, the patient he encountered in Hanoi and the professor from Guangzhou all subsequently died from the disease, tragically along with many others. As of June 2003 more than 8,400 SARS cases and 790 deaths have been reported worldwide.3

In the following week, news emerged in a piecemeal fashion in Hong Kong, placing considerable challenges on the authorities, but particularly those in charge of healthcare facilities. The first hospitals that had noticed something seriously wrong were those in Kowloon and the adjacent New Territories. The Prince of Wales Hospital, the teaching medical hospital for the Medical Faculty of the Chinese University of Hong Kong became seriously involved.5

In those settings, healthcare workers tending patients with the new pneumonia were regularly contracting the disease themselves. At the time, interpretation of this was that a hospital setting, by chance, creates optimum conditions necessary for the transmission of the virus. An alternative one, which greatly added to the fear associated with the causative agent, was to suggest that it almost had something like an intelligence which allowed it to outwit healthcare workers, a group of individuals whose skills are accorded a high degree of respect in Hong Kong. This feature is high on the list of those probably responsible for the near panic which ensued in the city.

On the morning of the 18th March, a Tuesday, the Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong Kong suspended all clinical teaching of medical students citing the presence of a new and serious infection within the hospitals of Hong Kong. Matters were brought to a head when it was learned that 17 medical students from the Medical Faculty of the Chinese University of Hong Kong had contracted the disease whilst observing the Metropole Hotel index patient who had been used as a teaching patient.

This was the moment when the Faculty of Dentistry and the Dental Hospital received first official indication of the operational implications of the outbreak. It was immediately agreed that the clinical teaching of dental students in the medical teaching hospital would likewise cease. At the same time high-level management meetings were convened between the Faculty and Dental Hospital authorities so the situation could be carefully reviewed with regard to dental clinical teaching in the building.

The initial working hypothesis at the first meeting was that the reports of this situation were probably being exaggerated. Nevertheless as a matter of routine prudence a number of steps were taken on that day. Firstly it was agreed that the high management meetings would be convened twice daily until the problem was resolved. As a matter of course, the possible immediate suspension of all clinical and clinical teaching procedures would be considered on each occasion. Furthermore it was established that the powers to immediately suspend teaching did in fact lie at Faculty level. The insurance position was clarified with regard to students and staff. It was apparent that cover was in place with the proviso that undue negligence on behalf of management could lead to liability in the case of a transmission. Additionally, messages were sent to all areas in the dental hospital requesting strict adherence to existing infection control procedures and as an additional precaution, orders were placed for several months' supplies of infection control material for immediate delivery that week.

With the benefit of hindsight these arrangements can be seen to have been correct and wise. The conclusion from this period is that in the absence of definite information regarding a threat, it is difficulty to justify ceasing activities in a large healthcare institution. However should there be warning signs, then any existing precautionary measures should be intensified and it should be ensured that subsequent management decisions to move to reduced activity or even closure can be easily carried out.

The disease enters the population

Throughout that week, and the one that followed, the sense of crisis amongst the Hong Kong population, rather than abating, became much more pronounced. On the morning of Monday 24th March, after a weekend when sober reflection might have calmed matters had the situation been exaggerated, it was announced that Dr William Ho, the head of the Hospital Authority had himself contracted Atypical Pneumonia whilst making morale raising visits to wards where SARS patients were being treated. Secondly, shortly after this event which was reported as a worldwide news item, the details of the now notorious Amoy Gardens outbreak began to emerge.

The story of the outbreak in Block E of this densely populated block of flats has been well documented in a report of the Department of Health of Hong Kong and a subsequent report by a team from the World Health Organisation. Both reports reach the same conclusions, namely that a SARS infected person visiting Amoy Gardens on the 24th and 28th February, had diarrhoea and infected the building's sewage system with the virus. Subsequently an unfortunate combination of dried-up lavatory and drainage U-pipes together with the arrangement of extractor fans in the flats had accelerated the spread of the disease in droplet form widely in the building.11

Two fearful though not necessarily correct conclusions could be drawn from the results of the Amoy Gardens outbreak in the form that information was to come to hand through the week beginning 26th of March. The first was (prior to the emergence of the sewage theory) the vertical spread seemed to contradict the view from the hospitals that was that only droplet transmission was involved with SARS. It seemed that the infinitely more dangerous airborne transmission was also taking place. Secondly as can be seen in Figure 2, at that time the rising curves of daily new cases from the hospital cluster and the Amoy Gardens cluster when combined looked like the beginning of an exponential upward curve. The extensive media coverage in Hong Kong was ensuring that all of this information was available to the public. At a time when the rest of the world was gripped by news of the Iraq War, the population of Hong Kong had good reason to believe that they were amongst the first in line to experience a killer disease which would sweep the world and rival the great influenza pandemic of 1918-19 in terms of fatalities.

This period of uncertainty, incomplete information and misinterpretation was very difficult to deal with. By extreme good fortune it only lasted for about two weeks. But it revealed the need for good communications within an organisation confronted with such a problem. To be effective, the communication had to be of a two-way nature with everyone being given opportunities to express opinions and to have them taken into account. To meet this need, a second tier of meetings were organised with senior faculty staff and hospital supervisory staff. In addition lunchtime forums were held for all staff and students. These were conducted in both English and Cantonese, the two working languages used in the building, reflecting the need to have cooperation from all levels of staff. Everyone's points of view was invited during the forums, and management explained how they were responding to the developing situation as well as taking on board useful suggestions from the audience.

It is a commonplace, often repeated, that good communication is important in large organisations. In the situation described it became essential. Everyone from the most junior to the most senior was not only potentially at risk, but could be a risk to others. The ideal arrangement in which to sort matters out is the open forum described above, but as will be seen even that was to become difficult as the crisis developed. Care was taken to disseminate regular updates in English and Chinese but written documents were not a substitute for the interactive discussion which is what is required.

Enhancing universal infection control.

During the course of this period it was decided to impose more control over treatments during which aerosols were created. Those procedures were kept to a minimum, and hand scaling was substituted for electronic and ultrasonic techniques wherever possible. Procedures needing water coolant were reduced and strict adherence to the requirement of assistance of all operators and use of high volume suction was enforced when such treatments were carried out. Use of rubber dam was stepped up and pre-rinse with antibacterial mouth rinses was considered. These additional recommendations preventing generation of aerosols have now been officially promulgated by the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, USA.12

Finally notices were placed at the entrance to the building and to clinical areas requesting that patients with fever or influenza-like symptoms should stay away. To ensure compliance the notice indicated that if such patients were to make contact by telephone they would be given a priority appointment 14 days after the original appointment. Similarly staff and students were requested to stay away from work if they had those symptoms.

As this period came to an end, the situation was appearing to be much worse than could have been initially imagined. In Hong Kong and elsewhere, fatalities were beginning to be announced daily, including the deaths of an appreciable number of healthcare workers. The numbers of new cases each day had fallen only to begin to rise again. The cause of the disease was still a matter of speculation.

In order to reduce risks of transmission against the background of uncertainty the decision was finally made on the afternoon of Thursday 27th March to cease all elective dental patient care including the treatment of patients by dental students. The following day would be used to wind down services and advise patients of the decision. The reduction to essential emergency services would commence on Monday 31st March. Thirty minutes after the decision was made the Heads of the Universities in Hong Kong announced that group teaching would cease from the Monday onwards. The schools in Hong Kong had reluctantly announced their closure on the same day.

At the same time the inappropriate nature of the large forum format that had been instituted to inform, advise, share experiences, persuade and eventually reach a view as to courses of action was recognised. Even meetings of much smaller numbers were being avoided. A further lesson learned from this phase is that while communication is of great importance under these situations, methods involving close contact in large groups may become inappropriate so alternative methods have to be established. Possibilities include e-mail, electronic forums, and for the non-computer literate, distributed intra-institutional videoconferencing arrangements.

This account will be concluded in Part 2: Control of the disease, then elimination in a future issue of the BDJ.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all staff and students of the Faculty of Dentistry, the University of Hong Kong, and The Prince Philip Dental Hospital, Hong Kong who contributed directly or indirectly to the contents of this article. Through their efforts the entire complement of the two organizations and all patients came safely through the crisis.

References

- 1.Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC, et al. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1977–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poutanen SM, Low DE, Henry B, et al. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epidemiology Program Office. Update: Outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome — Worldwide, 2003. Atlanta: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention 2003. MMWR 2003; 52: 241–248. [PubMed]

- 4.Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee N, Hui D, Wu A,, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL,, et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rota PA, Oberste MS, Monroe SS et al. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Sci 2003 May 30; 300: 1394–1399. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Samaranayake LP. Essential microbiology for dentistry. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RW, et al. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Lancet. 2003;361(9638):1519–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13168-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stohr KA. Multicentre collaboration to investigate the cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1730–1733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13376-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Centre for Infectious Disease. Interim domestic infection control precautions for aerosol-generating procedures on patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/aerosolinfectioncontrol.htm Last retrieval on 4th June 2003