Abstract

The potential for avian influenza H5N1 outbreaks has increased in recent years. Thus, it is paramount to develop novel strategies to alleviate death rates. Here we show that avian influenza A H5N1-infected patients exhibit markedly increased serum levels of angiotensin II. High serum levels of angiotensin II appear to be linked to the severity and lethality of infection, at least in some patients. In experimental mouse models, infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 virus results in downregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression in the lung and increased serum angiotensin II levels. Genetic inactivation of ACE2 causes severe lung injury in H5N1-challenged mice, confirming a role of ACE2 in H5N1-induced lung pathologies. Administration of recombinant human ACE2 ameliorates avian influenza H5N1 virus-induced lung injury in mice. Our data link H5N1 virus-induced acute lung failure to ACE2 and provide a potential treatment strategy to address future flu pandemics.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/ncomms4594) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Subject terms: Influenza virus, Medical research, Respiratory tract diseases

H5N1 avian influenza viruses can be highly pathogenic. Here, the authors show that H5N1 infection leads to increased serum levels of angiotensin II in patients and mice, and that administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 ameliorates lung injury in infected mice.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (doi:10.1038/ncomms4594) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

The H5N1 avian influenza virus has spread throughout the world, primarily infecting poultry and migratory birds1,2. Since 2003, more than 600 people worldwide have been identified to be infected with avian H5N1 influenza virus with higher mortality rate than that of seasonal flu and even the Spanish flu ( http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/EN_GIP_20131008CumulativeNumberH5N1cases.pdf). Human-to-human transmission of H5N1 viruses is rare and human infections have been primarily limited to people in very close contact with infected birds2,3. Many viruses, including H5N1, mutate readily and produce strains that are no longer manageable using vaccines or currently known antiviral drugs4. The apparent high lethality of H5N1 infections and their potential social impact make it paramount to identify common molecular disease mechanisms as well as new treatment options for H5N1 infections5.

The renin–angiotensin system (RAS) has an important role in maintaining blood pressure, cardiac homeostasis and fluid and salt balance6,7,8. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and its later discovered sibling ACE2 share homology in their catalytic domain and have opposite functions in the RAS9. ACE cleaves angiotensin I to generate angiotensin II, which is a key effector peptide and exerts multiple biological functions related to cardiovascular and renal biology10. In contrast, ACE2 cleaves a single amino acid residue from Angiotensin II to generate Ang1–7 and thereby negatively regulates the RAS by reducing Angiotensin II level11,12. Our previous studies using ACE2-knockout mice have demonstrated that ACE2 protects against acute lung injury (ALI) triggered by acid aspiration and sepsis13. Furthermore, ACE2 has been identified as the essential in vivo receptor for the SARS-Corona virus. SARS-CoV infections and the in vivo administration of the SARS-CoV spike protein reduce ACE2 expression14, suggesting that the RAS is involved in the pathogenesis of ALI and SARS-CoV infections14. Importantly, the administration of recombinant ACE2 has been proven beneficial in improving lung pathologies associated with SARS-CoV spike-, acid aspiration- and sepsis-induced ALI in different species13,14. Based on these data, ACE2 has now entered phase II clinical testing for the treatment of ALI in humans.

Human infections of influenza A virus subtype H5N1, also known as ‘bird flu’, causes severe pneumonia and ALI, ultimately resulting in death owing to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the most severe form of ALI15,16,17,18. In multiple species, the same clinical syndrome of acute lung failure/ARDS has been observed for various pathogenic conditions including sepsis, gastric acid aspiration or pulmonary infections with SARS-CoV and H5N1 bird flu13,14,19,20,21. In our accompanying paper, we observed elevation of serum angiotensin II in H7N9-infected patients, and more importantly, we showed that serum angiotensin II level was linked to disease severity and outcome22. We therefore wanted to determine whether ACE2 is also involved in H5N1-induced lung injury. Here we show that ACE2 plays an important role in H5N1 virus-induced ALI. In mice, experimental treatment with recombinant hACE2 ameliorates the disease and increases survival rate following H5N1 infection.

Results

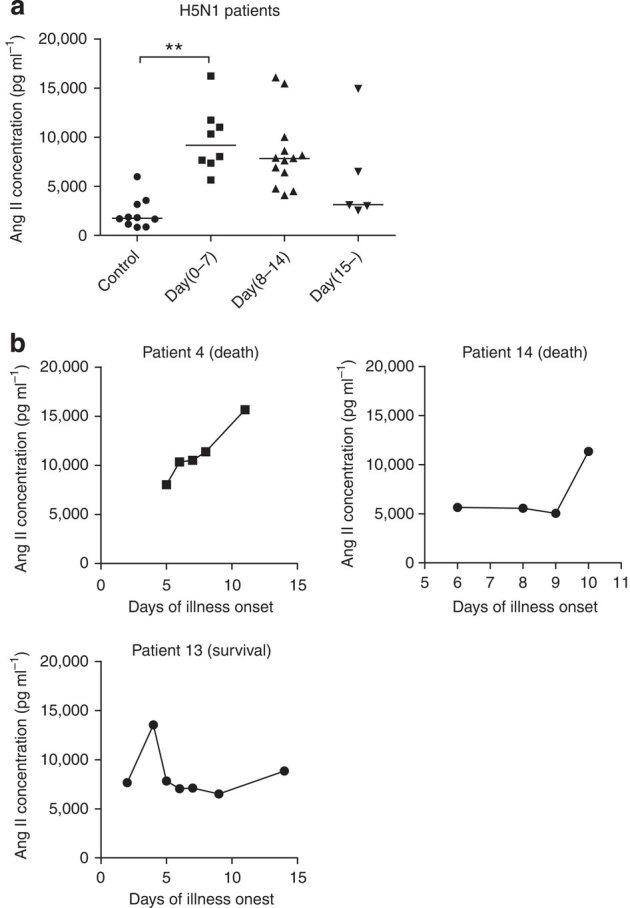

Serum level of angiotensin II is increased in H5N1 patients

To determine whether the RAS is indeed deregulated in humans with severe influenza, serum samples from 26 H5N1-infected patients were collected and divided into three groups; 0–7 days (n=8), 8–14 days (n=13) and more than 15 days (n=5) after illness onset. The level of angiotensin II, as a marker for RAS activation23,24, was significantly increased in the avian influenza A H5N1-infected patients when compared with healthy controls (n=10) (Fig. 1a, Table 1). Our data also indicated that serum angiotensin II levels might be linked to the severity and lethality of bird flu infections in patients (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1. Elevated serum angiotensin II levels in H5N1-infected patients.

(a) Angiotensin II levels in the sera of healthy volunteers (Controls, n=10) and H5N1-infected patients (n=26) divided into three groups according to plasma sampling times relative to the disease onset. Angiotensin II serum levels were determined using ELISA; bars represent the median value. **P<0.01 (Mann-Whitney U test). (b) Kinetics of angiotensin II serum levels in three H5N1-infected patients (patients 4, 13, and 14). Angiotensin II levels were determined using ELISA at the indicated time points after the onset of flu symptoms.

Table 1.

Clinical information for 10 healthy volunteers and 26 influenza H5N1-infected patients enrolled in this study.

| 10 healthy volunteers | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 35 (25–52) years |

| Interquartile range | 28–43 years |

| 15–30 years | 3 subjects (30%) |

| 31–50 years | 5 subjects (50%) |

| >50 years | 2 subjects (20%) |

| Male | 4 subjects (40%) |

| Female | 6 subjects (60%) |

| 26 influenza H5N1 virus-infected patients | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (range) | 27.5 (2–62) years |

| Interquartile range | 16.5–34.25 years |

| 2–14 years | 5 subjects (19.2%) |

| 15–30 years | 11 subjects (42.3%) |

| 31–50 years | 8 subjects (30.8%) |

| >50 years | 2 subjects (7.7%) |

| Male | 12 subjects (46.2%) |

| Female | 14 subjects (53.8%) |

| Clinical outcome | |

| Survival | 6 subjects (23.1%) |

| Death | 20 subjects (76.9%) |

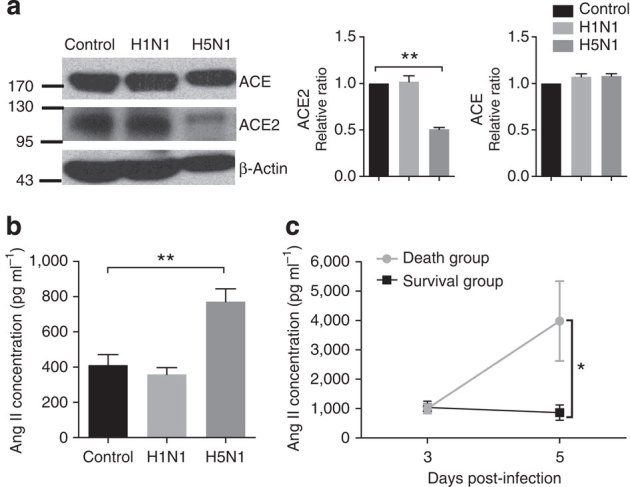

RAS is deregulated during H5N1 infection in a mouse model

To directly demonstrate that flu infections alter the RAS, we infected mice with live avian influenza A H5N1 virus. The infection of mice with the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus strain resulted in the rapid downregulation of ACE2 expression in the lungs 24 h after infection (n=3, Fig. 2a) and a concurrent increase of systemic angiotensin II levels in the serum 72 h after infection (n=5–6 per group, Fig. 2b). ACE expression was apparently not affected in the lungs of H5N1-infected mice (Fig. 2a). ACE2 expression in the lungs and the serum angiotensin II levels remained unchanged in mice challenged with the less pathogenic H1N1 virus (Fig. 2a,b). Furthermore, sera collected from infected mice on day 3 and day 5 showed that the changes in angiotensin II levels correlated with death (n=14) and survival (n=4) of H5N1-infected mice (Fig. 2c). Thus, similar to our human data, in our experimental mouse models the downregulation of ACE2 and elevation of serum angiotensin II level may also be correlated with the disease severity and lethality of bird flu infections.

Figure 2. Downregulated ACE2 expression and increased serum angiotensin II levels in mice infected with live H5N1 virus.

(a) Western blots of total lung samples obtained 24 h after intratracheal instillation of vehicle control (allantoic fluid (AF)), live H1N1 viruses or live H5N1 viruses (106 TCID50 in both cases). Blots are representative of three different mice for each treatment (full blots are provided as Supplementary Fig. 7). Bar graphs present quantitative analyses of ACE and ACE2 protein levels, which are presented as the mean ACE- and ACE2-to-β-actin ratios±s.e.m. (n=3 mice per treatment). **P<0.01 (two-tailed t-test). (b) Angiotensin (Ang) II levels in the serum of vehicle control and virus-challenged mice 72 h after virus or vehicle instillation. Angiotensin II levels were determined using radioimmunoassays (data are shown as mean±s.e.m.; n=5-6 mice per group). **P<0.01 (two-tailed t-test). (c) Angiotensin II levels in sera on day 3 (72 h) or day 5 (120 hrs) after infection with live H5N1 virus (106 TCID50). Angiotensin II levels were determined using radioimmunoassays. Death group, n=14, Survival group, n=4, data are shown as mean±s.e.m., *P<0.05 (two-tailed t-test). Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

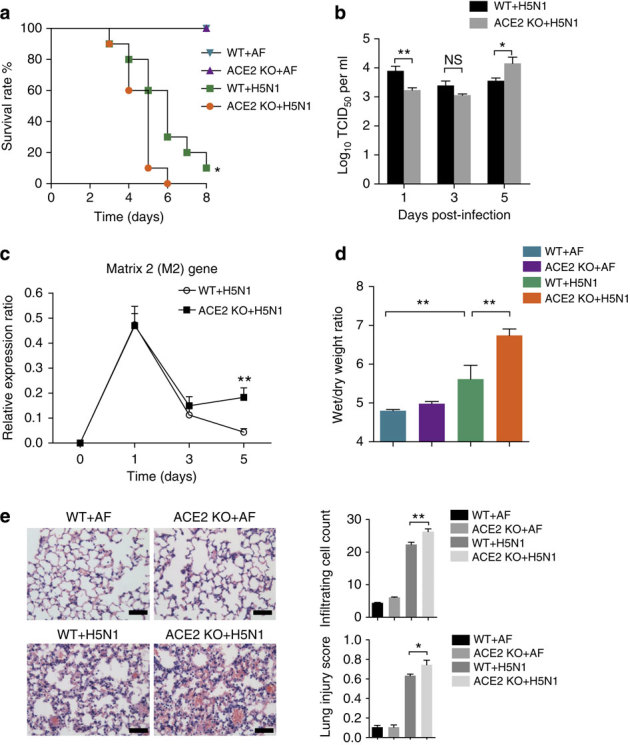

ACE2 deficiency exacerbates H5N1-induced lung injury

To determine whether ACE2 has a functional role in ALI induced by infections with live H5N1 avian flu viruses, we examined mice that are genetically deficient in ACE2 (ref. 25). H5N1 virus-infected ACE2-knockout mice (n=10) died significantly faster than the wild-type controls (n=10) (Fig. 3a). The H5N1 viral load detected in mice lung tissue of ACE2-knockout mice was significantly higher than that of wild-type mice lung 5 days after infection (n=3–5 per time point, Fig. 3b,c, Supplementary Fig. 1a). Moreover, the wet-to-dry lung tissue ratio, which is a measure of lung edema, was markedly higher in the ACE2-knockout mice 3 days after infection (n=4–6 per group, Fig. 3d), supporting the hypothesis that ACE2 has a protective role against H5N1 virus-induced acute lung failure. H5N1 challenge also resulted in increased inflammatory cell infiltration, and a more severe lung injury score (including increased alveolar wall thickness, formation of hyaline membranes and proteinaceous debris filling the airspaces), in the ACE2-knockout mice (n=3 per group, Fig. 3e). Thus, the genetic inactivation of ACE2 expression results in a lower survival rate and more severe ALI following respiratory H5N1 infections.

Figure 3. ACE2 deficiency increases the severity of H5N1-induced acute lung injury.

Wild-type (WT) and ACE2-knockout (ACE2 KO) mice were intratracheally instilled with vehicle control (allantoic fluid, AF) or live H5N1 virus (106 TCID50). (a) Kaplan-Meier survival curves were recorded. n=9–10 mice per group. *P<0.05 (log-rank test) when comparing the (ACE2 KO+H5N1) group with the (WT+H5N1) group. (b) Virus titers in wild-type or ACE2 KO mouse lung were assessed 1, 3 and 5 days after H5N1 infection, n=3–5 mice per time point (mean±s.e.m.). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (two-tailed t-test). (c) Relative mRNA expression levels of the influenza A matrix 2 (M2) gene in the lungs of wild type and ACE2 knockout mice at an indicated time were determined by real-time PCR, n=3–5 mice per time point (mean±s.e.m.). **P<0.01 (two-tailed t-test). (d) Wet to dry weight ratios of the lungs analyzed 3 days after intratracheal instillation of AF as a control or live H5N1 virus. n=4–6 mice per group (mean±s.e.m.). **P<0.01 (two-tailed t-test). (e) Representative images of the lung pathology of WT and ACE2 KO mice 3 days after intratracheal instillation of AF or live H5N1 virus. Scale bar=100 μm. The numbers of infiltrating cells per microscopic field (mean±s.e.m.; top panel) and lung injury scores (mean±s.e.m., bottom panel) are shown in the bar graphs. n=100 fields analyzed for three mice for each treatment. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (two-tailed t-test). Each experiment was repeated at least twice.

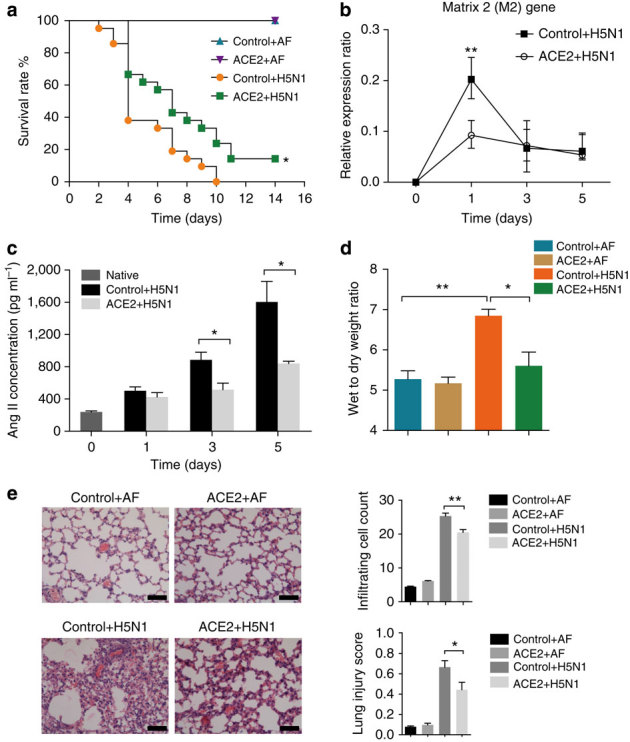

Recombinant hACE2 protects against H5N1 infection

Finally, we investigated whether recombinant human ACE2 can alleviate H5N1-induced pathologies. The administration of recombinant ACE2 protein (3 h prior to, 8 h and 3 days after infection, i.p. 100 μg kg−1) prolonged the overall survival time of mice infected with H5N1 virus (Fig. 4a) and decreased the viral replication in mice lungs after H5N1 viral infection (n=3–5 per time point, Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 1b). The weight loss of surviving hACE2 protein-treated mice was recovered (Supplementary Fig. 2). Treatment with recombinant hACE2 also markedly reduced the serum level of angiotensin II (n=3–4 per time point, Fig. 4c) and the development of edema 4 days after infection (n=3–4, Fig. 4d). The lung histopathology induced by H5N1 flu infection was also ameliorated (n=3, Fig. 4e). Moreover, hACE2 treatment improved the impaired lung functions of mice challenged with an inactivated H5N1 virus, as assessed via lung elastance (Supplementary Fig. 3). Of note, lung elastance is the reciprocal of lung compliance, a measure of the change in pressure per unit change in volume representing the stiffness of the lungs26. To assess whether administration of recombinant hACE2 is also effective after virus infection, we treated mice with recombinant hACE2 protein 1 h, 1 day and 2 days after H5N1 infection (i.p. 100 μg kg−1). Recombinant human ACE2 again ameliorated ALI induced in H5N1 infected mice (Supplementary Fig. 4). Further studies are required to assess the therapeutic efficacy of ACE2. Taken together, these data show that avian influenza A H5N1 virus infections cause severe acute lung failure, at least in part, by functionally altering the RAS via ACE2 expression and that H5N1-induced lung injury can be alleviated by the administration of recombinant human ACE2 protein.

Figure 4. Recombinant hACE2 reduces the severity of H5N1-induced acute lung injury.

BALB/c mice were injected with recombinant hACE2 (i.p., 100 μg kg−1) or allantoic fluid (AF) as a vehicle control (+BSA i.p., 100 μg kg−1) 3 h prior to, as well as 8 h and 3 days after intratracheal instillation of AF or live H5N1 virus (106 TCID50). (a) Kaplan-Meier survival curves. n=21 for the Control+H5N1 and ACE2+H5N1 groups, n=5 for the Control+AF and ACE2+AF groups. *P<0.05 when comparing the Control+H5N1 group with the ACE2+H5N1 group (Log-rank test). (b) Relative mRNA expression levels of influenza A M2 in the lungs of mice at the indicated time points using real-time PCR (mean±s.e.m.). n=3–5 mice per time point. **P<0.01 (two-tailed t-test). (c) Angiotensin II levels in the serum of mice were determined using radioimmunoassays at the indicated time points (mean±s.e.m.). n=3-4 mice per time point. *P<0.05 (two-tailed t-test). (d) Wet to dry lung weight ratios of the mice were assessed 4 days after AF or H5N1 instillation in the presence or absence of recombinant hACE2 (mean±s.e.m.). n=4-5 mice per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (two-tailed t-test). (e) Representative lung histopathology of AF and H5N1-challenged BALB/c mice left untreated or treated with recombinant ACE2 (i.p., 100 μg kg−1). Scale bar=100 μm. The numbers of infiltrating cells per microscopic field (mean±s.e.m.; top panel) and lung injury scores (mean±s.e.m.; bottom panel) are shown for day 4 after infection in the bar graphs. n=100 fields analyzed for three mice for each treatment. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (two-tailed t-test). Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Discussion

Our data establish an important role for ACE2 and the RAS in H5N1 virus-induced lung injury and death. The discovery that the severe acute lung injuries in patients with acid aspiration, sepsis or SARS-CoV infection and in those infected with H5N1 viruses share a common molecular mechanism, namely the downregulation of ACE2 leading to RAS activation, suggests that this pathogenesis mechanism may also explain other causes of ALI/ARDS. Further studies should include measuring other potential biomarkers in H5N1-infected patients. Previous studies have reported the NS1 protein of influenza can induce disease pathology27,28; however, we could not detect significant changes in ACE2 mRNA or protein expression following overexpression of the H5N1 proteins PB1, PB2, PA, NP, HA, NA, M1, M2, NS1 and NS2 (Supplementary Fig. 5, full blots are provided as Supplementary Fig. 6). Thus, the mechanism by which H5N1 infections result in ACE2 downmodulation requires further elucidation.

Given that flu viruses have high mutation rates, the identification of ACE2 as a common regulator of lung injury may also be useful to alleviate ALI/ARDS owing to mutated, newly emerging flu viruses including avian origin influenza virus H7N9 and/or currently unknown lethal lung pathogens29,30,31,32,33,34. Importantly, our data identify ACE2 as a potential novel mode of action to alleviate the symptoms of acute lung pathologies in individuals infected with highly lethal avian influenza A H5N1 viruses.

Methods

Influenza viruses and cells

The influenza viruses used in this study were A/New Caledonia/20/1999(H1N1) and A/chicken/Jilin/9/2004(H5N1). Live virus experiments were performed in biosafety level 3 facilities following governmental and institutional guidelines. All animal experiments were conducted with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval from the Institute of Military Veterinary, Academy of Military Medical Sciences. The viruses were propagated via inoculation into 10- to 11-day-old SPF embryonated fowl eggs via the allantoic route. Hemagglutinating allantoic fluid was collected from the eggs, and the viruses were then directly used as live viruses or inactivated using formaldehyde (only lung elastance assays were performed with inactivated virus). MDCK cells and 293T cells were purchased from Peking Union Medical College Cell Culture Center and cultured in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U ml−1 penicillin, and 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin at 37 °C.

Viral titration

Virus titers were obtained from supernatants of mouse lung homogenates of ACE2 KO mice or wild type mice on day 1, 3 and 5 after influenza H5N1 virus infection as described before35. Briefly, samples were added to the first column of the 96-well plate incubated with MDCK cells, then diluted with 10-fold dilutions; infected cells were maintained in culture for 96 h. Virus titers were calculated with the Reed-Muench method and were expressed as TCID50 per milliliter of supernatant.

Mouse infections

The animal experiments were conducted in the animal facility of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College, and the Institute of Military Veterinary Medicine, Academy of Military Medical Sciences, in accordance with governmental and institutional guidelines. Four-week-old male BALB/c mice were purchased from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, PUMC, Beijing. The ACE2-knockout mice have been previously described25 and were backcrossed onto a C57BL/6J background. C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Vital River, Beijing. All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility. Lung injury was induced via intratracheal instillation of allantoic fluid (AF) vehicle or virus (106 TCID50)14. In the rescue experiments, recombinant human ACE2 protein (100 μg kg−1, Apeiron Biologics) was injected intraperitoneally 3 h prior to, as well as 8 h and 3 day or 1 h, 1 day and 2 days after vehicle control or virus instillation.

Assessment of lung injury

Three or four days after the instillation of either the vehicle control or flu viruses, the mice were euthanized. The lungs were removed from the thoracic cavity and placed in a glass vial containing approximately 50 ml of fixative. Formalin-fixed mouse lungs were embedded in paraffin, coronally sectioned, and mounted on glass slides using standard techniques. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For each mouse, a slide containing one lung section was examined independently by three pathologists blinded to the treatments and genotypes. The numbers of inflammatory cells were counted in 100 microscopic fields, and lung injury scores were quantified36 inclusive of the alveolar wall thickness, hyaline membranes, and proteinaceous debris filling the airspaces, which gives an overall score of between 0 and 1. To determine serum angiotensin II levels, blood was collected into 1.5 ml tubes containing a mixture of peptidase inhibitors (0.30 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.32 M dimercaprol, and 0.34 M 8-hydroxyquinoline sulfate). For time-course experiments, 100 μl of blood were collected at each time point via tail puncture. Radioimmunoassays were used to measure angiotensin II in the serum37. For the assessment of pulmonary edema, the wet weight of the lungs was determined and then the lungs were dried in a 65 °C oven for 48 h to obtain the dry weight. Survival data were determined for each cohort and plotted as Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Lung elastance measurements

Mice were intratracheally treated with either the vehicle control or inactivated virus (10 μg g−1) after anesthesia. Lung elastance was measured via BUXCO Pulmonary Function Testing (PFT) every 30 min during spontaneous breathing periods for 4 h. For the rescue experiments, recombinant human ACE2 protein (100 μg kg−1) was intraperitoneally injected 20 min prior to instillation of the vehicle control or H5N1 virus infections.

Western blotting

For Western blotting, lung tissues were obtained 24 h after intratracheal instillation of the vehicle control or H1N1 and H5N1 viruses (106 TCID50). Tissues were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Triton X-100, 20 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, and protease inhibitors), the tissue lysates separated by SDS-PAGE, and the proteins transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were incubated with antibodies against ACE, ACE2, and β-actin, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies. The anti-ACE antibody (2E2, sc-23908, 1:1,000) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. The anti-ACE2 antibody (clone #460502, 1:300) was from R&D systems. The anti-β-actin antibody (clone AC-15, A5441, 1:10,000) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The anti-Flag-Tag mouse mAb (LK-ab002-100, 1:5,000) was from Multisciences for validation the plasmid transfection efficiency in 293T cell line. The anti-ACE2 antibody (K465, 1:500) was purchased from Bioworld. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies and Western Blotting Luminol Reagent were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibody binding was visualized using Kodak detection system and analyzed using Quantity One software.

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

For real-time quantitative PCR, lung tissues were obtained at the indicated time points after the intratracheal instillation of H5N1 viruses (106 TCID50) and 293T cells were grown in 12-well plates and samples analyzed 48 h after transfection with control plasmid or H5N1 virus protein-coding plasmids using X-treme GENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche) according to manufacturer’s instruction (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for a list of the viral protein-coding plasmids). The total RNA of lung tissues and cells were isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1.5 μg of total RNA with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). PCR amplification assays were performed with the LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche Applied Science, Cat.No.04707516001, USA) on a LightCycler 480 PCR System. PCR products were confirmed by sequencing. Lung tissue samples were normalized to β-actin levels, while 293T-cell samples were normalized to human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a reference. The specific primers used were as follows: M1 forward: 5′- CTCTCTATCATCCCGTCAG-3′; M1 reverse: 5′- GTCTTGTCTTTAGCCATTCC-3′; M2 forward: 5′- ATTGTGGATTCTTGATCGTC-3′; M2 reverse: 5′- TGACAAAATGACCATCGTC-3′; mice beta-actin forward: 5′- CTCTCCCTCACGCCATCC-3′; mice beta-actin reverse: 5′- CGCACGATTTCCCTCTCAG-3′; ACE2 forward: 5′- CAGTTGATTGAAGATGTGGAA-3′; ACE2 reverse: 5′- TGATATAGGAAGGATAGGCATT-3′; human GAPDH forward: 5′- CGGAGTAACGGATTTGGTC-3′; human GAPDH reverse: 5′- TGGGTGGAATCATATTGGAACAT-3′.

H5N1 patients and the assessment of patient sera

Sera were collected from 26 H5N1-infected flu patients and 10 healthy volunteers. H5N1 infections were confirmed by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) according to the Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of human avian influenza ( http://www.gov.cn/zlzt/gzqlg/content_107633.htm) and the WHO case definitions for human infections with influenza A(H5N1) virus ( http://www.who.int/influenza/resources/documents/case_definition2006_08_29/en/). Information about patients and healthy volunteers used as controls are presented in Table 1. Sera were collected by the China CDC after informed consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the institutional review board of China CDC. Angiotensin II levels in the sera were determined using ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (RapidBio Lab).

Statistical analyses

Angiotensin II values in H5N1-infected patients are shown as scatter diagram, the bar represents the median value. The data were analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test. Mouse data are shown as the mean values±s.e.m. Measurements at single time points were analyzed using ANOVA and, if they demonstrated significance, further analyzed using a two-tailed t-test. Time courses were analyzed using a repeated measures (mixed model) ANOVA with Bonferroni post-t-tests. All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Zou, Z. et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from lethal avian influenza A H5N1 infections. Nat. Commun. 5:3594 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4594 (2014).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figures 1-7 (PDF 1673 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank the Chinese influenza surveillance network for providing access to their collection of patient sera. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81230002 and 81300057), Ministry of Health (201302017), Ministry of Education (Biotherapy of 2011), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2009CB522105), and 111 project (B08007). D.L. acknowledges the support of the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (07pj14096). J.M.P. is supported by IMBA and the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013) under ERC grant agreement number 233407.

Author Contributions

C.J. conceived the project. Z.Z., Y.Y., Q.L., and Y.S. contributed to the experiments in mice and the analysis of the human data. H.Z., J.Z., F.G and Y.Z. performed the Western blot analysis and histopathology. Z.H. contributed to mouse husbandry. F.H. and N.L. performed the statistics. Y.S., T.B., and R.G. provided H5N1 patient samples and measured the angiotensin II levels in patient sera. X.L., C.L., X.J., Z.L., and H.L. assisted with the biosafety level 3 experiments. D.L. provided key ideas. C.J., J.M.P., and N.J. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. C.J., Z.Z., Y.Y., J.M.P., and N.J. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

J.M.P. holds shares in Apeiron Biologics which together with GSK are developing recombinant human ACE2 for acute lung injury patients. The remaining authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

Footnotes

Zhen Zou, Yiwu Yan, Yuelong Shu and Rongbao Gao: These authors contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Ningyi Jin, Email: ningyik@126.com.

Josef M. Penninger, Email: josef.penninger@imba.oeaw.ac.at

Chengyu Jiang, Email: jiang@pumc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Prosser DJ, et al. Wild bird migration across the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau: a transmission route for highly pathogenic H5N1. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e17622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Kerkhove MD, et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1): pathways of exposure at the animal-human interface, a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e14582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang B, et al. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of influenza virus receptors in trachea and lung tissues of humans, mice, chickens and ducks. Sci. China Life. Sci. 2012;55:612–617. doi: 10.1007/s11427-012-4341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chutinimitkul S, et al. H5N1 Oseltamivir-resistance detection by real-time PCR using two high sensitivity labeled TaqMan probes. J. Virol. Methods. 2007;139:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chmielewski R, Swayne DE. Avian influenza: public health and food safety concerns. Ann. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2011;2:37–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022510-133710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skeggs LT, Dorer FE, Levine M, Lentz KE, Kahn JR. The biochemistry of the renin-angiotensin system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1980;130:1–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9173-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corvol P, Williams TA, Soubrier F. Peptidyl dipeptidase A: angiotensin I-converting enzyme. Methods. Enzymol. 1995;248:283–305. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48020-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boehm M, Nabel EG. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2--a new cardiac regulator. New Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:1795–1797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr022472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imai Y, Kuba K, Ohto-Nakanishi T, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in disease pathogenesis. Circ. J. 2010;74:405–410. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-10-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sato T, et al. Apelin is a positive regulator of ACE2 in failing hearts. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:5203–5211. doi: 10.1172/JCI69608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwai M, Horiuchi M. Devil and angel in the renin-angiotensin system: ACE-angiotensin II-AT1 receptor axis vs. ACE2-angiotensin-(1-7)-Mas receptor axis. Hypertens. Res. 2009;32:533–536. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrario CM. ACE2: more of Ang-(1-7) or less Ang II? Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2011;20:1–6. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283406f57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuba K, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat. Med. 2005;11:875–879. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gambotto A, Barratt-Boyes SM, de Jong MD, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. Human infection with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus. Lancet. 2008;371:1464–1475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer TT, Ewig S, Rodloff AC, Muller EE. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and pneumonia: a comprehensive review of clinical data. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;43:748–756. doi: 10.1086/506430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 26 human cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in China. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Jiang C. Avian influenza H5N1: an update on molecular pathogenesis. Sci. China C. Life. Sci. 2009;52:459–463. doi: 10.1007/s11427-009-0059-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imai Y, et al. Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell. 2008;133:235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Y, et al. Inhibition of autophagy ameliorates acute lung injury caused by avian influenza A H5N1 infection. Sci. Signal. 2012;5:ra16. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao GF, Wu Y. Haunted with and hunting for viruses. Sci. China Life Sci. 2013;56:675–677. doi: 10.1007/s11427-013-4525-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang F, et al. Angiotensin II plasma levels are linked to disease severity and predict fatal outcomes in H7N9-infected patients. Nature Commun. 2014;5:3495. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Putnam K, Shoemaker R, Yiannikouris F, Cassis LA. The renin-angiotensin system: a target of and contributor to dyslipidemias, altered glucose homeostasis, and hypertension of the metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2012;302:H1219–H1230. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00796.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paul M, Poyan Mehr A, Kreutz R. Physiology of local renin-angiotensin systems. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86:747–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crackower MA, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is an essential regulator of heart function. Nature. 2002;417:822–828. doi: 10.1038/nature00786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gattinoni L, Chiumello D, Carlesso E, Valenza F. Bench-to-bedside review: chest wall elastance in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome patients. Crit. Care. 2004;8:350–355. doi: 10.1186/cc2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soubies SM, et al. Species-specific contribution of the four C-terminal amino acids of influenza A virus NS1 protein to virulence. J. Virol. 2010;84:6733–6747. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02427-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson D, Hossain MJ, Hickman D, Perez DR, Lamb RA. A new influenza virus virulence determinant: the NS1 protein four C-terminal residues modulate pathogenicity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:4381–4386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800482105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilleman MR. Realities and enigmas of human viral influenza: pathogenesis, epidemiology and control. Vaccine. 2002;20:3068–3087. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00254-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W, et al. Heterologous interactions between NS1 proteins from different influenza A virus subtypes/strains. Sci. China Life Sci. 2012;55:507–515. doi: 10.1007/s11427-012-4335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng J, Zhang Z, Zheng Z, Liu Y, Wang H. Methionine-101 from one strain of H5N1 NS1 protein determines its IFN-antagonizing ability and subcellular distribution pattern. Sci. China Life Sci. 2012;55:933–939. doi: 10.1007/s11427-012-4393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, et al. Environmental connections of novel avian-origin H7N9 influenza virus infection and virus adaptation to the human. Sci. China Life Sci. 2013;56:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s11427-013-4491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao HN, et al. Clinical findings in 111 cases of influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. New Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:2277–2285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Y, Gao GF. Lessons learnt from the human infections of avian-origin influenza A H7N9 virus: live free markets and human health. Sci. China Life Sci. 2013;56:493–494. doi: 10.1007/s11427-013-4496-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ottolini MG, et al. The cotton rat provides a useful small-animal model for the study of influenza virus pathogenesis. J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:2823–2830. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matute-Bello G, et al. An official American Thoracic Society workshop report: features and measurements of experimental acute lung injury in animals. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2011;44:725–738. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0210ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chappell MC, Millsted A, Diz DI, Brosnihan KB, Ferrario CM. Evidence for an intrinsic angiotensin system in the canine pancreas. J. Hypertens. 1991;9:751–759. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199108000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-7 (PDF 1673 kb)