Abstract

To evaluate current prevalence rates of 24 viruses and of the bacterium Mycoplasma pulmonis, the authors retrospectively surveyed serological data obtained from laboratory mice and rats housed in more than 100 western European institutions. Serum samples were submitted to the authors' institution for testing between January 2007 and June 2008. The prevalence of an infection was defined as the percentage of tested samples that yielded positive results for a specific agent. In mice, the most commonly detected infectious agents were murine norovirus (prevalence of 31.8%), mouse hepatitis virus (5.5%), mouse rotavirus (1.7%) and parvoviruses (1.0%). In rats, parvoviruses (12.1%) and M. pulmonis (3.6%) were the most prevalent infectious agents. Most rodent parvovirus infections could be attributed to mouse parvovirus in mice and to rat minute virus or to Kilham rat virus in rats. These data suggest the importance of up-to-date animal health monitoring programs and should stimulate the scientific community to further improve the microbiological quality of laboratory rodents.

Main

The microbiological status of experimental animals can critically influence the validity and reproducibility of research data1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Ensuring that animals are free of infectious agents that might interfere with research can reduce the number of animals required for study. This contributes substantially to animal welfare. An effective health monitoring program is crucial for the assessment of the health status of research subjects and for validation of infection control measures. Numerous publications provide guidance for the establishment of health monitoring programs that are tailored to rodents4,7,8,9,10,11,12. The Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations has published detailed recommendations that constitute common standards for health monitoring and reporting procedures in Europe10.

Current information on the prevalence of infectious agents must be made regularly available so that standard health monitoring recommendations can be kept up to date. For example, prevalence data can be used to develop a list of agents for which to test and to help determine the necessary frequency of testing in laboratory animal colonies. Information on the prevalence of infections may also contribute to a better understanding of their epidemiology.

Monitoring for viral agents and for several types of bacteria such as Mycoplasma pulmonis largely relies on the detection of specific antibodies that are produced during an infection. Many institutions have sent rodent serum samples to our laboratory for testing. Here we present a survey of data regarding the prevalence of antibodies against 24 viruses and M. pulmonis in sera of mice and rats from western European institutions. Data were collected from serological tests that were carried out in our laboratory during an 18-month period.

We emphasize that survey data were collected retrospectively from tests that were requested by the clients of BioDoc. Our clients selected the animals that were tested and indicated which infections to test for; therefore, the data do not represent a random population. Nevertheless, because data were taken from a large number of serum samples and institutions, we believe that these results should provide a good reflection of the current health status of laboratory mice and rats in western Europe.

Methods

Serum samples

We surveyed data from serum samples that were tested at BioDoc (Hannover, Germany) between January 2007 and June 2008. Samples were supplied by more than 100 different institutions, including universities, research centers, industry facilities, breeding companies and other diagnostic laboratories. The institutions were located in eight European countries: Austria, Denmark, Germany, Finland, France, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Most of the samples were submitted by German institutions. The number of samples that were tested for each infectious agent varied according to the clients' requests and ranged from 524 to 28,103 in mice and from 619 to 3,997 in rats. We defined the prevalence of a particular infection as the percentage of tested samples in which antibodies against the associated agent were detected.

Very little background information was provided with the serum samples. In most cases, the only details supplied were the name and address of the sender, the animal species and the agents to be tested for. Information concerning the colony, strain, age and gender of the animals from which the sera were derived could therefore not be evaluated.

Serological analyses

In general, the presence of agent-specific antibodies was determined using validated in-house immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) or hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assays as primary test methods. When necessary, in-house or commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were used as confirmatory test methods (Table 1). We carried out in-house assays according to published protocols13; commercial ELISAs (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were carried out according to the manufacturer's standard protocol.

Table 1.

Serological screening program

| Infectious agent | Animal species | Primary test | Confirmatory test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenoviruses | |||

| MAdV FL, MAdV K87 | Mouse, rat | IFA | ELISA |

| Cardioviruses | |||

| TMEV | Mouse | IFA | ELISA |

| TMEV, Theiler-like virusa | Rat | IFA | ELISA |

| Coronaviruses | |||

| Mouse hepatitis virus | Mouse | IFA | ELISA |

| Sialodacryoadenitis virus, rat coronavirus | Rat | IFA | ELISA |

| Ectromelia virus | Mouse | IFA | ELISA |

| Hantaviruses | Mouse, rat | IFA | ELISA |

| K virus | Mouse | HAI | ELISA |

| Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus | Mouse | IFA | ELISA |

| Mouse cytomegalovirus | Mouse | IFA | ELISA |

| Mouse polyomavirus | Mouse | IFA | None |

| Mouse rotavirus | Mouse | IFA | ELISA |

| Mouse thymic virus | Mouse | IFA | ELISA |

| Murine norovirus | Mouse | IFA | ELISA |

| Parvoviruses | |||

| Minute virus of mice, mouse parvovirus | Mouse | IFA | HAI, ELISAb |

| Kilham rat virus Toolan's H-1 virus, rat parvovirus, rat minute virus | Rat | IFA | HAI, ELISAb |

| Pneumonia virus of mice | Mouse, rat | IFA | ELISA |

| Reovirus type 3 | Mouse, rat | IFA | ELISA |

| Sendai virus | Mouse, rat | IFA | ELISA |

| Mycoplasma pulmonis | Mouse, rat | IFA | ELISA |

MAdV, mouse adenovirus; TMEV, Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus.

aOwing to cross-reactivity with TMEV (the GDVII virus strain), it was not possible to differentiate between infections with Theiler-like virus and with TMEV in rats.

bFor parvoviruses, HAI assays and ELISAs were used as secondary test methods to differentiate between virus serotypes.

Parvovirus infections in mice and rats were diagnosed using IFAs in which minute virus of mice or Kilham rat virus (respectively) were used as antigens. The IFA measures cross-reacting antibodies to various parvoviruses (by targeting highly conserved nonstructural viral proteins); therefore, if an IFA yielded a positive result, further testing was carried out to differentiate among serotypes. This was done by HAI assays (for minute virus of mice, Kilham rat virus, Toolan's H-1 virus and rat parvovirus) or by recombinant viral protein-2 ELISAs (for all known serotypes). These assays target viral capsid proteins that are serotype-specific.

Results

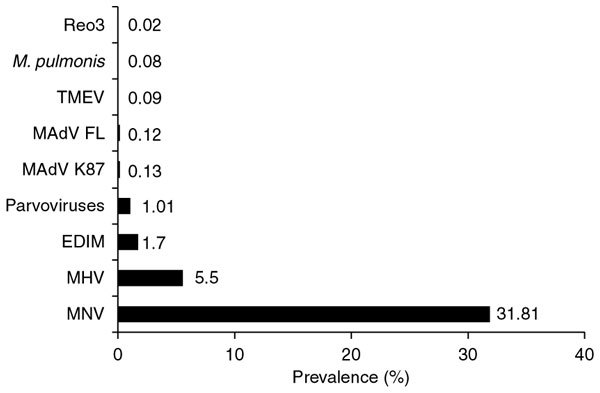

According to the serological data we obtained, the most prevalent infectious agents in mice were as follows (in descending order of prevalence; Fig. 1): murine norovirus (MNV; prevalence of 31.81%; 2,670 of 8,394 samples tested positive), mouse hepatitis virus (5.5%; 1,530 of 27,797 samples), mouse rotavirus (1.7%; 314 of 18,518 samples) and parvoviruses (1.01%; 285 of 28,103 samples). Antibodies against adenoviruses, Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus, M. pulmonis or reovirus type 3 were detected in fewer than 1% of serum samples. No other infectious agents were detected during the period of investigation. Regarding parvovirus infections in mice, 64.91% of infections (185 of 285 positive samples) could be attributed to mouse parvovirus, and 2.81% of infections (8 of 285 positive samples) could be attributed to minute virus of mice. For 32.28% of the positive samples (92 of 285), differentiation was not carried out, or results were ambiguous owing to positive findings for both minute virus of mice and mouse parvovirus.

Figure 1. Prevalence of agent-specific serum antibodies in mice.

EDIM, mouse rotavirus, MAdV, mouse adenovirus; MHV, mouse hepatitis virus; MNV, mouse norovirus; Reo3, reovirus type 3; TMEV, Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus.

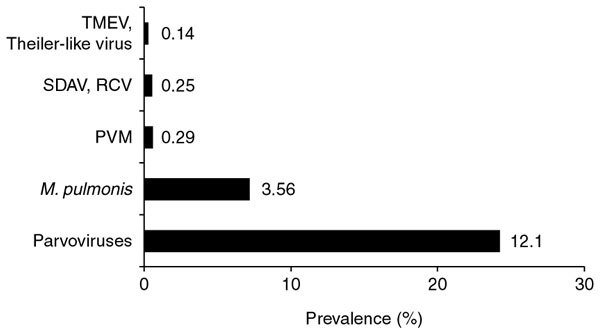

In rats, the most prevalent infectious agents were parvoviruses (prevalence of 12.1%; 482 of 3,997 tested samples) followed by M. pulmonis (prevalence of 3.56%; 105 of 2,949 samples; Fig. 2). Antibodies against pneumonia virus of mice, coronaviruses and cardioviruses were detected in fewer than 1% of serum samples. Antibodies against other agents were not found. Regarding parvovirus infections in rats, the majority of detected infections could be attributed to rat minute virus (54.15%; 261 of 482 positive samples), followed by Kilham rat virus (12.45%; 60 of 482 positive samples) and rat parvovirus (0.83%; 4 of 482 positive samples). Antibodies against Toolan's H-1 virus were not detected. For 32.57% of positive sera (157 of 482 positive samples), differentiation was not carried out, or results were ambiguous owing to positive findings for more than one parvovirus.

Figure 2. Prevalence of agent-specific serum antibodies in rats.

PVM, pneumonia virus of mice; RCV, rat coronavirus; SDAV, sialodacryoadenitis virus; TMEV, Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus.

Discussion

Serological assays are invaluable for detecting anti-bodies to all viruses and to a few types of bacteria (such as M. pulmonis) in laboratory animals11. Commonly used assays include IFAs, ELISAs, HAI assays, immunoblot assays and, more recently, multiplex fluorescent immunoassays14. The methods used must be selected carefully, as the methods may differ in sensitivity and specificity, and unexpected results should always be confirmed by a second method, by a second laboratory or by monitoring additional animals.

In the present survey, IFAs were generally used as a primary test method, and an HAI assay was used as a primary test method for detection of the K virus in mice. ELISAs were used for confirmatory testing, and ELISAs and HAI assays were used as secondary tests to distinguish between serotypes of parvoviruses (Table 1). IFAs are highly sensitive and are more likely than ELISAs and HAI assays to detect cross-reacting antibodies to closely related viruses. Thus, IFAs are useful for primary screening. This broader reactivity can be attributed to the use of virus-infected cells as antigen (containing both nonstructural and structural viral proteins). IFAs are subject to both specific and nonspecific reactivity; the morphology and location of fluorescence can be evaluated to differentiate between specific and nonspecific reactions. The main disadvantage of IFAs is that interpretation of their results is subjective and dependent on the experience of the observer.

Like IFAs, ELISAs are highly sensitive and are often used as a primary test. However, nonspecific cross-reactivity between irrelevant antibodies in the test sera and the antigen used can cause these assays to produce false positive results. This cross-reactivity can be reduced by using highly purified antigens prepared by recombinant technology. HAI assays are restricted to viruses that have hemagglutinins (proteins that bind red blood cells) on their surfaces. HAI tests lack sensitivity but are highly specific and can be used to differentiate between closely related viruses (such as rodent parvoviruses). As in the case of IFAs, interpretation of HAI test results is subjective.

Our serological survey suggests that many infections have been eliminated or have relatively low prevalence in laboratory rodents maintained in western Europe, whereas other infections are highly prevalent. In mice, the most prevalent infections we detected were those with MNV, mouse hepatitis virus, mouse rotavirus and parvoviruses. In rats, parvoviruses and M. pulmonis were most prevalent. Most rodent parvovirus infections could be attributed to mouse parvovirus in mice and to rat minute virus or to Kilham rat virus in rats. Several parvovirus infections in mice and rats could not be attributed to a single serotype by means of HAI assays or recombinant ELISAs; this might have resulted from a lack of specificity of these assays, from simultaneous infection with two (or more) parvoviruses or from infection with a yet unknown parvovirus. We note that the prevalence of rat parvoviruses, in particular that of rat minute virus, might be overestimated in this survey, because a large number of positive serum samples (n = 236) came from a single rat colony that was infected with the virus. On the other hand, we speculate that many serum samples submitted for testing were taken from colonies that were presumed to be 'clean', and that testing was aimed at confirming the seronegative status of these colonies. In our experience, monitoring for agents that are known to be endemic in a population is usually done infrequently or not at all. Therefore, the true prevalence rates of more commonly occurring agents (except rat parvoviruses) may be higher than those reported here.

Caution must also be exercised in the interpretation of serological results for M. pulmonis. Animals may be falsely seropositive owing to infection with other murine mycoplasmas (such as M. arthritidis) that cross-react with M. pulmonis antigenically15. Natural infections with other Mycoplasma species in mice and rats are rarely reported, however, and most samples that tested positive by IFA using M. pulmonis as an antigen yielded strong fluorescence signals in our analyses. We therefore consider that many (if not all) seropositive results can be attributed to infection with M. pulmonis.

An exact comparison with prevalence data from other recent studies16,17,18,19 in western Europe and North America is not possible, because the studies differ in their definitions of 'prevalence', which can indicate percentage of surveyed facilities in which a particular infection was detected, percentage of samplings (groups of serum samples taken from animals in a single population) in which at least one serum sample tested positive, or percentage of positive individual serum samples (as in this study). Nevertheless, all studies show similar findings with regard to the ranking of prevalence of viral infections. Currently, mouse hepatitis virus, parvoviruses (in particular, mouse parvovirus) and mouse rotavirus are among the most prevalent viral infections in mice, and parvoviruses, cardioviruses, pneumonia virus of mice and coronaviruses are most prevalent in rats. The occurrence of MNV in mice was not addressed in the above-mentioned surveys, as this agent has only recently been identified20. Our study indicates that the prevalence of MNV is greater than the prevalence of other viruses in mice. Notably, our finding of a prevalence rate of 31.8% is almost identical to that of a recent survey that found antibodies against MNV in 32.4% of more than 42,000 mouse sera tested21.

The prevalence of infections demonstrates the importance of health monitoring programs in laboratory animal facilities and should stimulate the scientific community to further improve the microbiological quality of laboratory rodents. The increased use of transgenic animals (with varying immunocompetence) and the exchange of animals and biological materials among institutions create a risk of transferring infectious agents; this heightens the importance of screening incoming animals and biological materials for the presence of infectious agents. Prevalence data should be considered in current health monitoring programs. They are an indicator of the risk of infection and can be used to aid in developing lists of agents for which to test and to help determine the necessary frequency of testing in laboratory animal colonies. A cost-conscious and reasonable approach would be to monitor frequently (quarterly, for example) for the most prevalent (high-risk) agents, such as MNV, mouse hepatitis virus, parvoviruses and mouse rotavirus in mice, and less frequently (annually or semiannually, for example) for rare (lower-risk) agents, while also considering the effect that each of these agents would have on the ongoing research or research staff. Finally, the discovery of 'new' agents, such as MNV, highlights the need for regular review and updating of health monitoring programs.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bhatt PN, Jacoby RO, Morse HC, New A. Viral and Mycoplasmal Infections of Laboratory Rodents: Effects on Biomedical Research. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamm TE. Complications of Viral and Mycoplasmal Infections in Rodents to Toxicology Research and Testing. 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lussier G. Potential detrimental effects of rodent viral infections on long-term experiments. Vet. Res. Contrib. 1988;12:199–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00362802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Research Council, Committee on Infectious Diseases of Mice and Rats. Infectious Diseases of Mice and Rats (National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1991).

- 5.Nicklas W, et al. Implications of infectious agents on results of animal experiments. Lab. Anim. 1999;33(Suppl. 1):39–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker DG. Natural Pathogens of Laboratory Animals: Their Effects on Research. 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen AK. Handbook of Laboratory Animal Science, Second Edition: Essential Principles and Practices. 2003. pp. 233–279. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weisbroth SH, Peters R, Riley LK, Shek W. Microbiological assessment of laboratory rats and mice. ILAR J. 1998;39:272–290. doi: 10.1093/ilar.39.4.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunstyr I, Nicklas W. Handbook of Experimental Animals: The Laboratory Rat. 2000. pp. 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicklas W, et al. FELASA recommendations for the health monitoring of rodent and rabbit colonies in breeding and experimental units. Lab. Anim. 2002;36:20–42. doi: 10.1258/0023677021911740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mähler M, Nicklas W. Handbook of Experimental Animals: The Laboratory Mouse. 2004. pp. 449–462. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaertner DJ, Otto G, Batchelder M, et al. The Mouse in Biomedical Research: Normative Biology, Husbandry, and Models. 2007. p. 385. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraft V, Meyer B. Diagnosis of murine infections in relation to test methods employed. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1986;36:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu CC, Franklin C, Riley LK. Multiplex fluorescent immunoassay for the simultaneous detection of serum antibodies to multiple rodent pathogens. Lab. Anim. (NY) 2007;36:36–38. doi: 10.1038/laban0907-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minion FC, Brown MB, Cassell GH. Identification of cross-reactive antigens between Mycoplasma pulmonis and Mycoplasma arthritidis. Infect Immun. 1984;43:115–121. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.115-121.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zenner L, Regnault J-P. Ten-year long monitoring of laboratory mouse and rat colonies in French facilities: a retrospective study. Lab. Anim. 2000;34:76–83. doi: 10.1258/002367700780577957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livingston RS, Riley LK. Diagnostic testing of mouse and rat colonies for infectious agents. Lab. Anim. (NY) 2003;32:44–51. doi: 10.1038/laban0503-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.choondermark-van de Ven EM, Philipse-Bergmann IM, van der Logt JT. Prevalence of naturally occurring viral infections, Mycoplasma pulmonis and Clostridium piliforme in laboratory rodents in Western Europe screened from 2000 to 2003. Lab. Anim. 2006;40:137–143. doi: 10.1258/002367706776319114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carty AJ. Opportunistic infections of mice and rats: Jacoby and Lindsey revisited. ILAR J. 2008;49:272–276. doi: 10.1093/ilar.49.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karst SM, Wobus CE, Lay M, Davidson J, Virgin HW. STAT1-dependent innate immunity to a Norwalk-like virus. Science. 2003;299:1575–1578. doi: 10.1126/science.1077905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson KS. Murine norovirus, a recently discovered and highly prevalent viral agent of mice. Lab. Anim. (NY) 2008;37:314–320. doi: 10.1038/laban0708-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]