Summary:

CD4+CD56+ malignancy is a rare neoplasm with a typical clinical pattern, an aggressive course and high early relapse rate despite good initial response to chemotherapy. In this review, the impact of different therapeutic approaches on clinical outcome has been studied. We evaluated 91 published cases and our own six patients in terms of clinical features, immunophenotype/cytogenetics and treatment outcome. Treatment was divided into four groups: (A) chemotherapy less intensive than CHOP; (B) CHOP and CHOP-like regimens; (C) therapy for acute leukemia; (D) allogeneic/autologous stem cell transplantation. The median overall survival was only 13 months for all patients. Patients with skin-restricted disease showed no difference in the overall survival from patients with advanced disease (17 and 12 months, respectively). Age ⩾60 years was a negative prognostic factor. Age-adjusted analysis revealed improved survival after high-dose chemo/radiotherapy followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation when performed in first complete remission. This therapeutic approach should be recommended for eligible patients with CD4+CD56+ malignancy. For older patients the best treatment option is still unknown.

Keywords: CD4+CD56 malignancy, stem cell transplantation, chemotherapy

Main

CD4+CD56+ hematopoietic malignancies are now regarded as a distinct clinicopathologic entity. CD4, a glycoprotein expressed on helper T cells and a subset of monocytes and thymocytes, has been found in T cell leukemia/lymphoma and in acute myeloid leukemia. Among leukocytes, the neural cell adhesion molecule CD56 is expressed predominantly on natural killer (NK) cells and on a small subset of T cells (CD8+ cytotoxic/suppressor cells and a subgroup of χδ-T-cells). Its expression on leukemia and lymphoma cells characterizes a heterogeneous group of malignancies. Coexpression of both antigens is very rare. The classification of CD4+CD56+ lymphomas leads to a somewhat confusing terminology for this entity: blastic/blastoid NK-cell lymphoma/leukemia, cutaneous monomorphous CD4+ CD56+large cell lymphoma, agranular NK-cell lymphoma, etc. In the new WHO classification, CD4+CD56+neoplasms are probably included in the ill-defined category of blastic NK-cell lymphomas. CD4+CD56+malignancies must be distinguished from the nasal type of extranodal NK/T cell lymphomas and aggressive NK-cell leukemias that may be closely related entities occurring frequently in the Asian population (Table 1). While nasal-type NK/T cell lymphoma is characterized by preferential involvement of the nasopharynx with angiocentric and angioinvasive growth resulting in extensive coagulative necroses, aggressive NK-cell leukemia usually presents with constitutional symptoms, and leukemic course. Both tumors show CD2+CD3-CD56+ phenotype and are almost constantly associated with EBV. In contrast to CD4+CD56+ lymphoma, they often present in middle-aged females.1,2,3,4

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of CD4+CD56+ malignancy

| CD4+CD56+ | Aggressive NK-cell lymphoma/leukemia | Nasal and nasal-type NK-cell lymphoma | Blastic NK-cell lymphoma/leukemia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 67 years (median) | Young | Middle-aged | Middle-aged to elderly |

| Sex ratio | Males predominate | No sex predilection or slight male predominance | Males predominate | No sex predilection |

| Involved sites | Skin, BM, LN | BM, liver, spleen | Nose, nasopharynx, palate, skin, soft tissue, GI tract, testis | Skin, LN, BM, soft tissue |

| Morphology | Lymphoblastoid/pleomorphic monotonous medium-sized cells with fine chromatin | Medium-sized cells with round or irregular nuclei | Polymorphic, pleomorphic | Lymphoblastoid monotonous medium-sized cells with fine chromatin |

| Phenotype | CD2−/+, sCD3−, cCD3+/−, CD4+, CD56+, TdT+/−, TIA-1−, Granzyme B− | CD2+, sCD3−, cCD3−, CD4−, CD56+, TdT−, TIA-1+, Granzyme B+ | CD2+, sCD3−, cCD3+, CD4−/+, CD56+, TdT−, TIA-1+, Granzyme B+ | CD2−/+, sCD3−, cCD3+/−, CD4−/+, CD56+, TdT+/−, TIA-1−, Granzyme B− |

| Association with EBV | Extremely rare | Strong | Strong | None |

| TCR gene | Germline | Germline | Germline | Germline |

| Genetics | No specific single chromosomal aberrations, often 5q, 6q, 9, 12p, 13q, and 15q | No specific chromosomal aberrations, often del(6) | No specific chromosomal aberrations, often del(6), inv(6) | No specific chromosomal aberrations |

| Clinical course | Aggressive with relapse | Highly aggressive | Locally destructive to aggressive | Aggressive |

The question of tumor cell origin of the CD4+CD56+ neoplasm has been debated for a long time. Some authors proposed precursor NK-cell origin, whereas others suggested that CD4+CD56+ tumor cells derived from myelo-monocytic precursor cells. Petrella et al5 performed extensive flow cytometric analysis in 14 cases and found very high levels of CD123 expression suggesting that this disease derives from plasmacytoid monocytes. Furthermore, some authors have described reactive CD4+CD56+ cells within kidney allografts during tubular necrosis and rejection6 and within liver biopsies in patients with chronic active hepatitis B.7 They hypothesized that prolonged antigen stimulation may produce this unusual phenotype. Recently, Chaperot et al8 using flow cytometry and in vitro assays suggested that CD4+CD56+ malignancies arise from transformed cells of the lymphoid-related plasmacytoid dendritic cell subset.

Little is known about the etiology and pathogenesis of CD4+CD56+ neoplasms. EBV and human herpesvirus-6 are not detectable. Human T cell lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) was found in one case,9 while others10,11,12 failed to detect this virus. In general, (latent) viral infection does not seem to play an important role in the pathogenesis of this disease.

Clinically, CD4+CD56+ neoplasms usually involve the skin, spread rapidly to extracutaneous sites, and have a poor outcome. Therapeutic strategies vary widely from symptomatic treatment and local radiation therapy to allogeneic stem cell transplantation, but optimal treatment remains to be defined.

Since Adachi et al10 reported the first CD4+CD56+ malignancy in 1994, 91 cases have been published (Table 2). This review summarizes the clinical and phenotypic features and treatment outcome for the malignancy including our own six patients.

Table 2.

Published cases of CD4+CD56+ malignancies

| Authors | Year | n | Chemotherapy | Irradiation | CR/PR | Median survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adachi et al10 | 1994 | 1 | CHOP | No | 0/1 | 24 |

| Hayashi et al9 | 1994 | 1 | CHOP | Yes | 1/0 | 53 |

| Brody et al13 | 1995 | 1 | COP | No | 0/0 | 6.5 |

| Nakamura et al14 | 1995 | |||||

| Kobashi et al15 | 1996 | 3 | CAMBO-VIP (1), THPOC (1), CHOP+BMT (1) | ND | 3/0 | 17+ |

| Savilo et al16 | 1995 | 1 | RT | Yes | 1/0 | 22+ |

| Dummer et al17 | 1996 | 1 | IFN-α | Yes+PUVA | 0/0 | 17+ |

| Emile et al18 | 1996 | 2 | n.d. | ND | n.d. | 4 |

| DiGiuseppe et al19 | 1997 | 4 | Prednisone (2), COP+mitoxantrone (1), unknown (1) | No | 2/1 | 8 |

| Savoia et al12 | 1997 | 4 | CHOP (1), ACOP-B (1), P-VEBEC (1) | Yes (1) | 3/0 | 8 |

| Drénou et al20 | 1997 | 1 | CHOP+MTX, cytarabine, etoposide, allogeneic BMT | TBI | 1/0 | 14+ |

| Uchiyama et al21 | 1998 | 1 | IL-2 | Yes | 1/0 | 20 |

| Bagot et al22 | 1998 | 1 | COP+C | No | 1/0 | 16 |

| Kameoka et al23 | 1998 | 2 | CHOP (1), CHOP-like (1) | No | 1/0 | 8 |

| Bastian et al24 | 1998 | 1 | No | Yes | 1/0 | 18+ |

| Ko et al25 | 1998 | 1 | CHOP | No | 1/0 | 32+ |

| Petrella et al11 | 1999 | 7 | COP (1), CP (1), CVBM (1), CCVP (2), DC (1), LDC (1) | No | 7/0 | 17 |

| Mukai et al26 | 1999 | 1 | Cis-VACD autoPBSCT | No | 1/0 | 40 |

| Mhawech et al27 | 2000 | 1 | CHOP | No | 0/1 | ND |

| Nagatani et al28 | 2000 | 4 | ACOMP-B (19, COP (1), etoposide, prednisone, IFN-α/γ | Yes (1) | 1/2 | 12.5 |

| Falcão et al29 | 2000 | 3 | ALL-regimen (1) CHOP (2) | No | 1/0 | 3 |

| Kojima et al30 | 2000 | 1 | Cis-VACD (1) | TBI | 2/0 | 32.5 |

| Ginarte et al31 | 2000 | 1 | Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, MTX; i.th. MTX, hydrocortisone, cytarabine | No | 1/0 | 14+ |

| Rakozy et al32 | 2001 | 2 | CHOP (1) | No | 1/0 | 17.5 |

| Yamada et al33 | 2001 | 2 | Steroids and chemotherapy (1), CHOP (1) | Electron beam therapy (1) | 1/1 | 31 |

| Kimura et al34 | 2001 | 1 | ALL-regimen | ND | 1/0 | 13+ |

| Honda et al35 | 2001 | 1 | CHOP+sobuzoxane | No | 0/1 | ND |

| Alvarez-Larran et al36 | 2001 | 1 | CHOP | No | 1/0 | 18 |

| Kato et al37 | 2001 | 1 | CHOP+HD Dexa CCE, +autologous PBSCT | No | 1/0 | 13 |

| Aoyama et al 38 | 2001 | 1 | Vincristine, prednisone | No | 1/0 | 6 |

| Feuillard et al39 | 2002 | 21 | Multiple | No | 2/17 | 12 |

| Khoury et al40 | 2002 | 6 | CHOP (2), hyper-CVAD (1)+MTX, cytarabine (2), POMP (1) | Yes (1) | 7.5 | |

| Chen et al41 | 2002 | 1 | None | Yes | 1/0 | ND |

| Chang et al42 | 2002 | 1 | CHOP | Yes | 1/0 | 5+ |

| Bayerl et al43 | 2002 | 3 | CHOP (1) CHOP, ifosfamide, etoposide (1), cytarabine, daunorubicin (1) | No | 2/0 | 21+ |

| Petrella et al5 | 2002 | 7 | NA (1), DC+RT (1), mini-CEOP (1), ACVBP (1),AVDB (1), CEP (1), HU (1) | No | 3/0 | 8 |

ACOMP-B: ACOP-B+methotrexate; ACOP-B: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, bleomycin; ACVBP: daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, bleomycin; prednisone, ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; AVDB: adriamycin, vincristine, daunorubicin, bleomycin; CAMBO-VIP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicine, methotrexate, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, ifosfamide, prednisone; CCE: carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide; CEP: cyclophosphamide, eldisine, prednisolone; CHEP: cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine, prednisone; CHOP: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone; Cis-VACD: cisplatin, vindesine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone; CMi: cytarabine, mitoxantrone; COP: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone; COP-C: COP+ chlorambucil; CP: chlorambucil, prednisone; CVBM: cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, mitoxantrone; DC: daunorubicin, cytarabine; HU: hydroxyurea; Hyper-CVAD: CHOP with hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide; IC: idarubicin, cytarabine; IFN-α: interferon-alpha; IFN-γ: interferon-gamma; IL-2: interleukin-2; i.th.: intrathecal; LAC: lomustine, adriamycin, cytarabine; LDC: DC+lomustine; Mini-CEOP: cyclophosphamide, etoposide, vincristine, prednisone; MTX: methotrexate; POMP: mercaptopurine, vincristine, prednisone; PUVA: psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy; P-VEBEC: prednisone, vinblastine, epirubicin; bleomycin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide; methotrexate, RT: radiotherapy; THPCOP: cyclophosphamide, THP-doxorubicin, vincristine prednisolone; ND: not determined; CR: complete remission; PR: partial remission.

Clinical features

CD4+CD56+ neoplasms generally affect older patients with a median age of 67 years (range 6–89 years). Males are affected almost three times as often as females (m:f ratio: 2.7:1). The clinical manifestations of this disease show a characteristic pattern. The vast majority of patients initially presents with cutaneous lesions of nonspecific morphology and distribution. At diagnosis, in almost 80% of patients, the disease has already spread to extracutaneous sites, most frequently to bone marrow and lymph nodes (>50% each), followed by spleen and liver (11–20%). Other organs such as nasopharynx, tonsils, CNS, lacrimal glands, muscle, or gynecological tract are only sporadically affected.

According to the Ann Arbor classification, 24% of patients are diagnosed in stage I (with only a single skin lesion), 7% patients in stage II, 2% patients in stage III, and 66% patients in stage IV. In contrast to other lymphoid malignancies, B symptoms such as fever, night sweat, and weight loss are rare.

Immunophenotype and cytogenetics

Morphologically, the malignant cells consist of monomorphic medium-sized blasts with finely dispersed chromatin. These cells consistently express CD4 and CD56, while (surface) CD3 and B cell markers are absent. HLA-DR usually is found, whereas CD8 expression is normally negative. Further NK-cell (CD16, CD57) or myeloid (eg CD34) markers are absent. Pan-T cell markers as CD2, CD5, and CD7 are rarely expressed. Phenotypic data are summarized in Table 3. Expression of T cell markers other than CD4 (eg CD5, CD7, CD8) does not influence clinical course. T cell marker positive and negative patients (balanced according to age and gender) show identical overall survival curves (data not shown). Studies for EBV by immunohistochemistry (latent membrane protein) or in situ hybridization of EBV-encoded RNA (EBER probes) are negative except for two cases indicating no association with EBV infection.

Table 3.

Immunophenotype and EBV diagnostic of CD4+CD56+ malignancies

| Pat. | CD2 | CD3 | CD4 | CD5 | CD7 | CD8 | CD16 | CD56 | CD45 RO | HLA-DR | CD34 | CD68 | CD20 | EBV (LMP) | EBER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published cases | 24/87 28% | 0/91 0 | 90/91 100% | 3/83 4% | 33/81 40% | 1/85 1% | 2/71 3% | 91/91 100% | 4/40 10% | 73/78 94% | 1/60 2% | 23/45 51% | 0/70 0 | 3/18 18% | 0/38 0 |

| Own cases | 5/5 | 0/6 | 6/6 | 1/6 | 0/5 | 0/6 | 0/1 | 6/6 | 1/6 | 4/4 | 1/6 | 5/6 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 |

| a | − | − | + | − | − | − | ND | + | − | ND | − | − | − | − | − |

| b | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| c | − | − | + | − | − | − | ND | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| d | − | − | + | − | − | − | ND | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − |

| e | − | − | + | − | − | − | ND | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| f | ND | − | + | − | ND | − | ND | + | + | ND | − | + | ND | ND | ND |

Analysis of surface antigens and EBV-LMP was performed by immunohistochemistry. EBER (Epstein–Barr virus-encoded RNA) was analysed by in situ hybridization. ND=not determined.

The genetic alterations in CD4+CD56+ neoplasms are largely unknown and in many studies cytogenetic data are missing. However, some authors describe different chromosomal aberrations. In a recent study, Leroux et al44 using conventional cytogenetic and 24-color FISH analyses identified six chromosomal regions frequently affected in these neoplasms. In their series, reproducible loss of chromosomal material occurred on chromosomes 5q, 6q, 9, 12p, 13q, and 15q in 14 of 21 patients. They concluded that there was no single consistent chromosomal aberration, but that a combination or accumulation of certain genomic imbalances might be specific in CD4+CD56+ malignancy.44

Treatment outcome

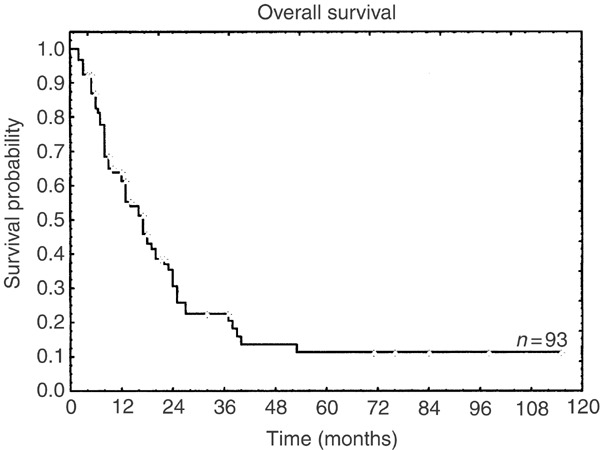

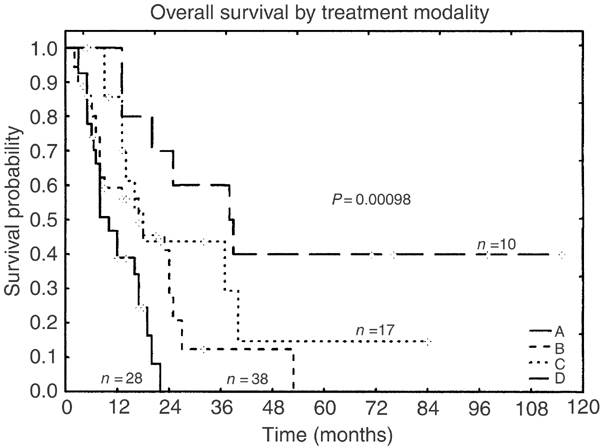

Since there is no consensus for optimal treatment in CD4+CD56+ neoplasms, therapeutic approaches for CD4+CD56+ malignancy vary widely from irradiation in localized stages to myeloablative therapy. Although the initial response rate to treatment is high with almost 70% complete remissions (CR) and 10% partial remissions (PR), only about 20% of patients show a sustained remission at the last follow-up (median observation 16 months). Most patients relapse and subsequently die of progressive disease. Patients with disease limited to the skin only show a slightly better median overall survival than patients with advanced disease (17 and 12 months, respectively), but the difference is not significant (log-rank test, data not shown). In general, outcome is poor with a median overall survival of 13 months reflecting the aggressive course of the disease (Figure 1). To investigate the impact of different therapies on outcome, treatment of published cases can be separated into four groups according to the intensity of the chemotherapy.

Local therapy or systemic therapy ‘less than CHOP’: Primarily older patients are treated with local therapy or systemic therapy ‘less than CHOP’. The median age in this group is 79 years. Chemotherapy regimens were heterogeneous, but mostly cyclophosphamide-based. Some patients only received local radiation (n=5), steroid therapy (n=1), or supportive care (n=1). Despite an overall high response rate of almost 80% (68% CR, 11% PR), this group showed a very poor outcome. Only two authors reported sustained CR (7%) after this therapy; one young patient with skin-restricted disease had radiotherapy; another, a 72-year-old man with widespread disease, was treated with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, vincristine and intrathecal prophylaxis.24,31 However, the observation time for the two patients was only 14 and 18 months, respectively. The median overall survival for all evaluable patients is only 9 months and Kaplan–Meier curves do not suggest curative potential for this therapeutic approach (Figure 2). Table 4 summarizes the clinical data for this treatment group (group A).

CHOP and CHOP-like regimens: CHOP/CHOP-like chemotherapy was used most frequently in CD4+CD56+ malignancies (group B). However, compared to less aggressive therapies (group A) this moderately intensive treatment did not result in better response rates or survival benefit. The overall response rate in almost 40 evaluable patients was about 70% (55% CR), but sustained CR was only observed in one patient within this treatment group (Table 5) with a short follow-up of only 4 months.39 Taken together, CHOP (-like) therapy, like less aggressive treatments, did not seem to provide curative potential.

Intensive acute leukemia protocols: Since CD4+CD56+ neoplasms usually show an aggressive course with frequent bone marrow involvement, intensive treatment according to acute leukemia seems an appropriate therapeutic approach (group C). Different protocols were investigated with a high CR rate of 94%. Sustained CR can be achieved with these regimens in about one-third of patients. Although median observation time for these responders was only 7.5 months, Falcão et al29 reported a young boy continuing in CR for seven years following therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Table 6 shows the data for this treatment group.

Myeloablative therapy: Experience with myeloablative therapy in CD4+CD56+ malignancy is limited to 10 patients (four autologous and six allogeneic transplants) that are summarized in Table 7. All patients in whom data on myeloablative therapy were evaluable underwent total body irradiation and all but one received high-dose cyclophosphamide (alone or in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents). The entire group (group D) had a median survival of 31.5 months. However, only two of the six patients receiving allogeneic transplant relapsed (median overall survival 38.5 months) compared to three relapses in the four patients with autologous transplant (median survival 16.5 months). Autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (APBSCT) with one exception did not lead to long-lasting disease-free survival. However, in the allogeneic setting, all but one patient remained disease-free, if the transplantation has been performed in first remission. However, this treatment is restricted to younger patients as reflected by the median age of 28.5 years in this group.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve of the overall survival for 93 evaluable published and own patients. In four patients follow-up data were missing.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of the overall survival for different therapies: A – chemotherapy less intensive than CHOP, including symptomatic therapy and local irradiation; B – CHOP and CHOP-like regimens; C – therapy for acute leukemia; D – autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Table 4.

Group A: patients treated with local therapy or systemic therapy ‘less than CHOP’

| Pat. | Age/sex | Cutaneous manifestations | Extracutaneous manifestations | Initial therapy | CR/PR | Survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 63/m | + | + | COP | No | 61/2 |

| 3 | 47/f | + | − | RT, PUVA, IFN-α | No | 17+ (AWD) |

| 4 | 81/f | + | + | Prednisone | PR | 10 |

| 5 | 82/m | + | + | COP+mitoxantrone | CR | 8 |

| 6 | 79/m | + | + | Prednisone | CR | 3 |

| 8 | 72/m | + | + | RT | No | 5 |

| 12 | 89/m | + | − | IL-2, RT | CR | 20 |

| 15 | 21/f | + | − | RT | CR | 18+ |

| 16 | 86/f | + | + | COP | CR | 5 |

| 18 | 67/f | + | − | COP-C | CR | 17 |

| 19 | 84/m | + | + | CP | CR | 5 |

| 20 | 65/f | + | + | COP-C | CR | 17 |

| 25 | 83/m | + | + | COP | No | 19 |

| 26 | 89/f | + | + | RT | PR | 5 |

| 27 | 82/m | + | + | Etoposide + prednisone +IFNα/γ | CR | 8 |

| 36 | 67/f | + | − | COP-C | CR | 16 |

| 49 | 76/m | − | + | Symptomatic | No | 3 |

| 51 | 81/f | + | + | COP | CR | 12 |

| 53 | 69/m | + | + | COP | CR | 12 |

| 58 | 79/m | + | − | Cyclophosphamide, etoposide, Prednisone | CR | 8 |

| 67 | 67/m | + | + | 6-Mercaptopurine, MTX, prednisone | PR | 12+ |

| 68 | 70/m | + | + | COP | CR | 7 |

| 70 | 79/m | + | + | Vincristine, prednisone | CR | 6 |

| 77 | 86/m | + | − | RT | CR | ND |

| 87 | 64/m | + | + | CEP | CR | 6+ (PD) |

| 88 | 88/f | + | − | HU | No | 8 |

| 89 | 72/m | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, MTX, vincristine + i.th. | CR | 14+ |

| 90 | 81/m | + | − | RT | CR | 22+ (AWD) |

| n=28 | Med. 79 | 27/28 96% | 19/28 68% | 19CR 68% | Med. OS 9 | |

| m:f 18:10 | 3PR 11% | CR at last follow-up 2/28 (7%) |

AWD: alive with disease; CEP: cyclophosphamide, eldisine, prednisolone; COP: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone; COP-C: COP+ chlorambucil; HU: hydroxyurea; IFN-α: interferon-alpha; IFN-γ: interferon-gamma; IL-2: interleukin-2; i.th: intrathecal; MTX: methotrexate; PUVA: psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy; RT: radiotherapy; CR: complete remission; PR: partial remission; ND: not determined.

Table 5.

Group B: patients treated with CHOP or CHOP-like regimens

| Pat. | Age/sex | Cutaneous manifestations | Extracutaneous manifestations | Initial therapy | CR/PR | Survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67/m | + | + | CHOP | PR | 24 |

| 9 | 78/m | + | + | ACOP-B | CR | 8 |

| 10 | 72/m | + | − | CHOP | CR | 17+(AWD) |

| 11 | 60/m | + | + | P-VEBEC | CR | 11 |

| 13 | 21/f | + | + | CHOP-14 | CR | 14+relapse |

| 14 | 81/m | + | + | CHOP-like | ND | 2 |

| 17 | 38/m | + | − | CVBM | CR | 27 |

| 24 | 71/m | + | + | ACOMP-B | PR | 17 |

| 28 | 18/m | − | + | CHOP | CR | 32+relapse |

| 31 | 18/m | + | + | CHOP | No | 2 |

| 32 | 68/m | + | + | CHOP-bleomycin | No | 3 |

| 33 | 57/m | + | + | CAMBO-VIP | CR | 32+relapse |

| 34 | 78/m | + | + | CHOP | CR | 9+relapse |

| 37 | 47/m | + | − | CHOP | ND | 5 |

| 40 | 67/m | + | + | Electron beam + CHOP | PR | 25 |

| 42 | 65/m | − | + | CHOP + sobuzoxane | PR | + |

| 44 | 55/m | + | + | Cis-VACD | CR | 25 |

| 47 | 53/m | − | + | CHOP+RT | CR | 53 |

| 48 | 45/f | − | + | CHOP | PR | + |

| 54 | 75/m | − | + | Etoposide, cytarabine, ifosfamide | CR | 6 |

| 55 | 72/m | + | + | CHEP | PR | 23 |

| 60 | 74/m | + | − | Etoposide, ifosfamide | CR | 17 |

| 63 | 75/f | + | + | Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, daunorubicin | No | 9 |

| 65 | 82/m | + | + | CHOP without prednisone | CR | 4+ |

| 71 | 56/m | + | + | Hyper-CVAD | CR | 24 |

| 72 | 61/m | + | + | Hyper-CVAD | ND | 6 |

| 73 | 73/m | + | + | Hyper-CVAD, MTX, cytarabine | CR | 24 |

| 74 | 52/m | + | + | Hyper-CVAD, MTX, cytarabine | CR | 3 |

| 75 | 85/f | + | + | CHOP + RT | No | 7 |

| 76 | 77/m | + | + | CHOP | No | 8 |

| 78 | 19/f | + | − | CHOP | CR | 5+ AWD |

| 79 | 71/m | + | + | CHOP | CR | 21+(SD) |

| 81 | 66/m | + | − | CHOP | No | 13 |

| 84 | 72/m | + | + | Mini-CEOP | No | 3 |

| 85 | 33/f | + | + | ACVBP | CR | 27 |

| 86 | 77/m | + | − | AVDB | No | 7 |

| 91 | 73/m | + | + | CHOP | CR | 18 |

| c | 74/f | + | + | Vincristine, prednisone, CHOP | CR | 8 |

| n=38 | Med. 67.5 | 34/38 89% | 31/38 82% | 21CR 55% | Med. OS 13 | |

| m:f 31:7 | 6PR 16% | CR at last follow-up 1/38 (3%) |

ACOMP-B: ACOP-B + methotrexate; ACOP-B: doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, bleomycin; ACVBP: daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, bleomycin; AVDB: adriamycin, vincristine, daunorubicin, bleomycin; CAMBO-VIP: Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicine, methotrexate, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, ifosfamide, prednisone; CHEP: cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine, prednisone; CHOP: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone; Cis-VACD: cisplatin, vindesine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone; CVBM: cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycinn, mitoxantrone; Hyper-CVAD: CHOP with hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide; Mini-CEOP: cyclophosphamide, etoposide, vincristine, prednisone; MTX: methotrexate; P-VEBEC: prednisone, vinblastine, epirubicin, bleomycin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide; RT: radiotherapy; CR: complete remission; PR: partial remission; ND: not determined.

Table 6.

Group C: patients treated with an intensive acute leukemia protocol

| Pat. | Age/sex | Cutaneous manifestations | Extracutaneous manifestations | Initial therapy | CR/PR | Survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 49/f | + | + | DC | CR | 9 |

| 22 | 37/m | + | − | LDC | CR | 32+ (AWD) |

| 30 | 8/m | + | + | Brazilian ALL-regimen (GTBLI-93) | CR | 84+ |

| 41 | 34/m | + | + | JALSG ALL87 regimen | CR | 13+ |

| 50 | 8/m | + | + | CMi | CR | 37 |

| 52 | 68/f | + | + | LAC | CR | 22 |

| 57 | 55/m | + | + | LAC | CR | 16 |

| 59 | 14/m | + | + | Vincristine, prednisone, daunorubicin, asparaginase | CR | 10+ |

| 61 | 74/f | + | + | Vincristine, 6-mercaptopurine,cyclophosphamide, cytarabine | CR | 5+ |

| 62 | 67/m | + | + | IC | CR | 5+ |

| 64 | 60/m | + | + | LAC | CR | 9 |

| 66 | 56/m | + | + | DC | CR | 13 |

| 82 | 8/m | + | + | CMi | CR | 33 |

| 83 | 62/m | + | − | DC+RT | No | 13 |

| a | 60/m | + | + | Vincristine, daunorubicin, prednisone, HAM | CR | 40 |

| b | 71/m | + | + | DA, ETI | CR | 18 |

| f | 67/f | + | − | DA | CR | 4+ (under therapy) |

| n=17 | Med. 56 m:f 13:4 | 14/14 | 14/17 82% | 16CR 94% | Med. OS 13 CR at last follow-up 6/17 (35%) |

ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AWD: alive with disease; CMi: cytarabine, mitoxantrone; DA: daunoblastin, cytarabine; DC: daunorubicin, cytarabine; ETI: etoposide, thioguanin, idarubicin; HAM: high-dose cytarabine, mitoxantrone; IC: idarubicine, cytarabine; JALSG: Japan Adult Leukemia Study Group; LAC: lomustine, adriamycin, cytarabine; LDC: DC+lomustine; RT: radiotherapy; CR: complete remission; PR: partial remission.

Table 7.

Group D: patients treated with myeloablative protocols

| Pat. | Age/sex | Cut. manif. | Extracut. manif. | High-dose chemotherapy±TBI | Source of stem cells | BM/peripheral | Time of Tx | Survival (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | 29/m | − | + | HD cyclophosphamide+TBI | Allogeneic | BM | First CR | 76+ in CR |

| 35 | 24/f | + | + | HD cyclophosphamide melphalan+TBI* | Allogeneic | BM | First CR | 115+ in CR* |

| 38 | 35/m | + | − | ND | Allogeneic | BM | Second CR | 39 died of sepsis in PD |

| 56 | 6/f | − | + | Aracytidine, melphalane+TBI* | Allogeneic | BM | First CR | 98+ in CR |

| 69 | 28/m | + | − | HD cyclophosphamide+ TBI* | Allogeneic | BM | First CR | 38 AWD relapse at 12 months |

| 80 | 29/m | + | − | ND | Allogeneic | BM | Third CR | 25 died in CR due to ARDS |

| d | 23/m | + | + | Busulfan, thiotepa, fludarabine, ATG − TBI | Allogeneic | Peripheral | Second CR | 20 died in CR therapy-related |

| 23 | 25/m | + | + | HD cyclophosphamide, etoposide+TBI | Autologous | Peripheral | PR after First relapse | 71+ in CR* |

| 43 | 51/m | + | + | HD cyclophosphamide, carboplatin, etoposide, dexamethasone − TBI* | Autologous | Peripheral | First CR | 13 PD died of pneumonia |

| d | 23/m | + | + | HD cyclophosphamide+TBI | Autologous | Peripheral | First CR | 20 relapse see above |

| e | 32/m | + | + | HD cyclophosphamide+TBI | Autologus | Peripheral | First CR | 13 DOD |

| n=10 | Med. 28.5 m:f 8:2 | 8/10 80% | 7/10 70% | allo:auto 7:4** | BM/peripheral 6:5** | Med. OS 31.5 CR at last follow-up 5/10 (50%) |

*Personal communication.

**Patient d underwent both autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantion.

Cut. manif: cutaneous manifestations; extracut. manif.=extracutaneous manifestations; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; ATG: antithymocyte globulin; AWD: alive with disease; BM: bone marrow; DOD: died of disease; HD: high dose; TBI: total body irradiation; Tx: transplantation; CR: complete remission; PR: partial remission; PD: progressive disease; ND: not determined.

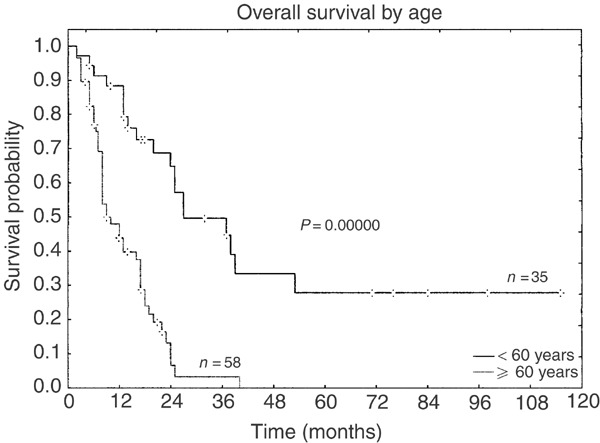

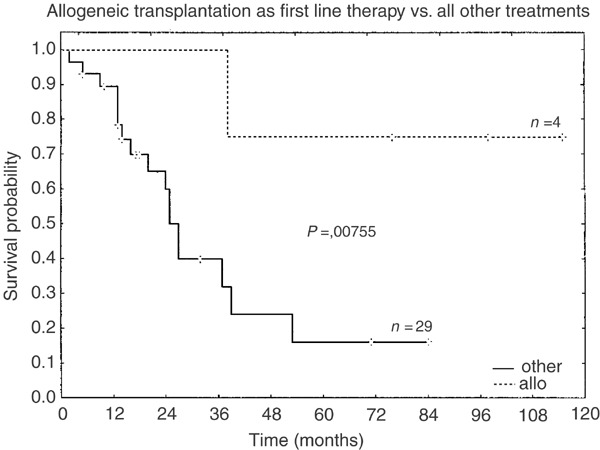

Taken together, overall response rate (CR and PR after initial therapy) is high regardless of therapy and does not show pronounced differences in the four groups. On the other hand, maintenance of CR is better, with more aggressive treatment (group A: 7%, group B: 3%, group C: 35%, and group D: 50%, respectively). Figure 2 shows Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the different treatment groups. The overall survival between groups C and D was significantly higher than in groups A and B. Group D alone was also significantly superior to groups A, B, and C. However, age ⩾60 years was a negative prognostic factor in CD4+CD56+ neoplasms that strongly influences outcome (Figure 3) and median age decreased when more intensified therapy was provided: 79 years (group A), 67.5 years (group B), 52 years (group C), and 28.5 years (group D), respectively. Elderly patients survived for a median of 9 months (range 2–40 months) compared to younger patients with a significantly longer median survival of 18 months (range 2–84 months; P<0.0001). Older age in less aggressive treatment groups might at least partly explain poor outcome. Therefore, we performed an age-adjusted evaluation that revealed significant superiority in the overall survival only for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in the first remission (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves of the overall survival according to age (including all treatment groups).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves of the overall survival for patients <60 years showing survival benefit for allogeneic transplantation.

Conclusions

CD4+CD56+ neoplasms are a distinct entity with a characteristic CD4+CD56+CD3-phenotype, usually with rapid and aggressive course and poor outcome. Since skin-restricted disease shows no better outcome than primarily disseminated disease, CD4+CD56+ neoplasms must be considered as a primarily systemic disease. Despite initial good response to various (chemo-) therapies, median overall survival is only 13 months and therapeutic guidelines are not yet defined, mainly because of its rare occurrence.

Treatment that is more aggressive than the CHOP regimen (groups C and D) results in better response rates compared to less intensive therapies (groups A and B). While intensive therapy for acute leukemia (group C) only enhances the rate of sustained CR, myeloablative treatment (group D) also leads to a marked increase of median survival of 38.5 months. However, age ⩾60 years is a negative prognostic factor, which is consistent with findings in malignant lymphoma and myeloid malignancies. In an age-adjusted evaluation only allogeneic stem cell transplantation in first CR showed significant superiority in terms of the overall survival compared to all other treatments in patients <60 years. Since allogeneic stem cell therapy is limited to younger patients and most patients with CD4+CD56+ malignancy are in their seventh decade of life, the vast majority of patients are not eligible for this otherwise promising therapeutic option.

Our own experience confirms the above results (Table 8). Patients initially were treated either with CHOP or combination chemotherapy designed for acute leukemia. All patients died with a median survival of 15.5 months including one patient who underwent autologous PBSCT in the first remission. Another patient who relapsed after autologous PBSCT achieved a second CR following allogeneic peripheral stem cell transplantation, but died as a complication of treatment on day +52. To our knowledge, this is the first patient with CD4+CD56+ malignancy who received peripheral allogeneic stem cell transplantation and who underwent both autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation.

Table 8.

Clinical features of own cases

| Pat. | Age/sex | Cutaneous lesions | Extracutaneous manifestations | Genetics * | Initial treatment | Response | Site of relapse | Salvage therapy | Outcome (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 60/m | Thorax | BM, LN, nasopharynx | mos46,XY/45,XY, t(12;15) (p11;q11) | Vincristine, daunorubicin, prednisolone, HAM | CR | BM | ICE | 40 DOD |

| b | 71/m | Trunk | BM, leukemia, LN | 46, XY | DA, ETI | CR | Skin, BM | Cytarabine, CHOP, FC | 18 DOD |

| c | 74/w | Scalp, trunk, upper arms | BM, leukemia | mos46,XX/44,XX,-9 | CHOP | CR | BM, leukemia, spleen | Palliative | 8 DOD |

| d | 23/m | Diffuse | BM | 46, XY | CHOP, MTX (i.th.) autologous PBSCT | CR | Skin, BM, LN, CNS, spleen | ESHAR allo-TX | 20 in CR d+52 therapy related |

| e | 32/m | Face, lower legs | BM, leukemia LN, CNS | rev ish dim 5q21-q32rev ish dim 9 rev ish dim | CHOP, MTX (i.th.) autologous PBSCT | CR | Skin, BM, leukemia, LN, CNS, | T-ALL regimen | 13 DOD |

| 13q rev ish enh 14q32 | |||||||||

| f | 67/f | Mamma | No | ND | DA | CR | 4+under therapy |

*In all cases except case e, classical cytogenetics was performed. Case e was investigated by comparative genomic hybidization.

ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; ATG: antithymocyte globulin; BM: bone marrow; CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; CNS: central nervous system; DA: daunorubicin, cytarabine; DOD: died of disease; ESHAP: etoposide, methylprednisone, cytarabine, cisplatin; ETI: idarubicine, thioguanine, etoposide; FC: fludarabine, cyclophosphamide; HAM: high-dose cytarabine, mitoxantrone; ICE: idarubicin, cytarabine, etoposide; i.th: intrathecal; LN: lymph nodes; MTX: methotrexate; CR: complete remission.

In summary, allogeneic stem cell transplantation in the first CR should be recommended for younger patients with CD4+CD56+ neoplasms with curative intent. For patients not eligible for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, the best therapy still is unknown. Owing to a high early relapse rate, we would not recommend autologous PBSCT for these patients. Whether nonmyeloablative therapy followed by allogeneic transplantation or maintenance therapy will improve outcome remains to be evaluated.

References

- 1.Chan JK. Natural killer cell neoplasms. Anat Pathol. 1998;3:77–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe ES, Chan JKC, Su I-J. Report of the workshop on nasal and related extranodal angiocentric T/natural killer cell lymphomas: Definitions, differential diagnosis, and epidemiology. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:103–111. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199601000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology & Genetics. Tumours of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 2001. pp. 214–215. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rüdiger T, Weisenburger DD, Anderson JR. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (excluding anaplastic large-cell lymphoma): results from the non-Hodgkin's lymphoma classification project. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:140–149. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrella T, Comeau MR, Maynadié M. ‘Agranular CD4+ CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm’ (blastic NK-cell lymphoma) originates from a population of CD56+ precursor cells related to plasmocytoid monocytes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:852–862. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachetoni A, Lionetti P, Cinti P. Homing of CD4+CD56+ T lymphocytes into kidney allografts during tubular necrosis or rejection. Clin Transplant. 1995;9:433–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnaba V, Franco A, Paroli M. Selective expansion of cytotoxic T lymphocytes with a CD4+CD56+ surface phenotype and a helper type 1 profile of cytokine secretion in the liver of patients chronically infected with hepatitis B virus. J Immunol. 1994;152:3074–3087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaperot L, Bendriss N, Manches O. Identification of a leukemic counterpart of the plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood. 2001;97:3210–3217. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.10.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi K, Nakamura S, Koshikawa T. A case of neural cell adhesion molecule-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma associated with human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type 1 showing an unusual involvement of the gastrointestinal tract during the course of the disease. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:1251–1253. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adachi M, Maeda K, Takekawa M. High expression of CD56 (N-CAM) in a patient with cutaneous CD4-positive lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 1994;47:278–282. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830470406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrella T, Dalac S, Maynadié M. and the Groupe Français d’Etude des Lymphomes Cutanés (GFELC). CD4+ CD56+ cutaneous neoplasm: A distinct hematological entity? Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:137–146. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199902000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savoia P, Fierro MT, Novelli M. CD56-positive cutaneous lymphoma: a poorly recognized entity in the spectrum of primary cutaneous disease. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:966–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brody JP, Allen S, Schulman P. Acute agranular CD4-positive natural killer cell leukemia. Cancer. 1995;75:2474–2483. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950515)75:10<2474::AID-CNCR2820751013>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura S, Suchi T, Koshikawa T. Clinicopathologic study of CD56 (NCAM)-positive angiocentric lymphoma occurring in sites other than the upper and lower respiratory tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:284–296. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobashi Y, Nakamura S, Sasajima Y. Inconsistent association of Epstein–Barr virus with CD56 (NCAM)-positive angiocentric lymphoma occurring in sites other than the upper and lower respiratory tract. Histopathology. 1996;28:111–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.278324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savilo E, Meyer RM, Soamboosrup P. CD2+, CD3−, CD56/NCAM+ malignant lymphoma with TCRβ gene rearrangement: a case report. Am J Hematol. 1995;50:209–214. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dummer R, Potoczna N, Häffner AC. A primary cutaneous non-T, non-B CD4+, CD56+ lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:550–553. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1996.03890290084011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emile J-F, Boulland M-L, Haioun C. CD5− CD56+ T-cell receptor silent peripheral T-cell lymphomas are natural killer cell lymphomas. Blood. 1996;87:1466–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiGiuseppe JA, Louje DC, Williams JE. Blastic natural killer leukemia/lymphoma: A clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1223–1230. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199710000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drénou B, Lamy T, Amiot L. CD3−CD56+ Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas with an aggressive behaviour related to multidrug resistance. Blood. 1997;8:2966–2974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uchiyama N, Ito K, Kawai K. CD2−, CD4+, CD56+ agranular natural killer cell lymphoma of the skin. Am J Dermatol. 1998;20:513–517. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199810000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagot M, Bouloc A, Charue D. Do primary cutaneous non-T non-B CD4+CD56+ lymphomas belong to the myelo-monocytic lineage? (letter) J Invest Dermatol. 1998;11:1242–1244. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kameoka J, Ichinohasama R, Tanaka M. A cutaneous agranular CD2− CD4+ CD56+ ‘lymphoma’. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:478–488. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/110.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bastian BC, Ott G, Müller-Deubert S. Primary cutaneous natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:109–111. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko YH, Kim SH, Ree HJ. Blastic NK-cell lymphoma expressing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase with Homer-Wright type pseudorosettes formation. Histopathology. 1998;33:547–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukai HY, Kojima H, Suzukawa K. High-dose chemotherapy with peripheral blood stem cell rescue in blastoid Natural Killer cell lymphoma. Leukemia Lymphoma. 1999;32:583–588. doi: 10.3109/10428199909058417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mhawech P, Medeiros J, Bueso-Ramos C. Natural killer-cell lymphoma involving the gynecologic tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1510–1513. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-1510-NKCLIT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagatani T, Okazawa H, Kambara T. Cutaneous monomorphous CD4- and CD56-positive large-cell lymphoma. Dermatology. 2000;200:202–208. doi: 10.1159/000018383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falcão RP, Garcia AB, Marques MG. Blastic CD4 NK cell leukemia/lymphoma: a distinct clinical entity. Leuk Res. 2002;26:803–807. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(02)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kojima H, Mukai HY, Shinagawa A. Clinicopathological analyses of 5 Japanese patients with CD56+ primary cutaneous lymphomas. Int J Hematol. 2000;72:477–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginarte M, Abalde MT, Peteiro C. Blastoid NK cell leukemia/lymphoma with cutaneous involvement. Dermatology. 2000;201:268–271. doi: 10.1159/000018475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rakozy C, Mohamed AN, Vo TD. CD56+/CD4+ lymphomas and leukemias are morphologically, immunophenotypically, cytogenetically, and clinically diverse. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:168–176. doi: 10.1309/FMYW-UL3G-1D7J-ECQF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamada O, Ichikawa M, Okamoto T. Killer T-cell induction in patients with blastic natural killer cell lymphoma/leukaemia: implications for successful treatment and possible therapeutic strategies. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:153–160. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimura S, Kakazu N, Kuroda J. Agranular CD4+CD56+ blastic natural killer leukaemia/lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:228–231. doi: 10.1007/s002770000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Honda S, Ito Y, Otawa M. CD56- and CD4-positive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of probable T-cell origin. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2001;42:420–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Álvarez-Larrán A, Villamor N, Hernández-Boluda JC. Blastic natural killer cell leukemia/lymphoma presenting as overt leukaemia. Clin Lymphoma. 2001;2:178–182. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2001.n.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kato N, Yasukawa K, Kimura K. CD2−CD4+CD56+ hematodermic/hematolymphoid malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:231–238. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.110897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aoyama Y, Yamane T, Hino M. Blastic NK-cell lymphoma/leukemia with T-cell receptor γ rearrangement. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:752–754. doi: 10.1007/s00277-001-0380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feuillard J, Jacob M-C, Valensi F. Clinical and biological features of CD4+CD56+ malignancies. Blood. 2002;99:1556–1563. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.5.1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khoury JD, Medeiros LJ, Manning JT. CD56+ TdT+ Blastic natural killer cell tumor of the skin. A primitive systemic malignancy related to myelomonocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2002;94:2401–2408. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen N, Agosti S, Doll D. Blastic natural killer cell leukaemia/lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2002;116:241. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang SE, Choi HJ, Huh J. A case of primary cutaneous CD56+, TdT+, CD4+, blastic NK-cell lymphoma in a 19-year-old woman. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:72–75. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200202000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bayerl MG, Rakozy CK, Mohamed AN. Blastic natural killer cell lymphoma/leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;11:41–50. doi: 10.1309/UUXV-YRL8-GXP7-HR4H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leroux D, Mugneret F, Callanan M. on behalf of Groupe Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique. CD4, CD56+ DC2 acute leukaemia is characterized by recurrent clonal chromosomal changes affecting 6 major targets: a study of 21 cases by the Groupe Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique. Blood. 2002;99:4154–4159. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.11.4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]