Abstract

Human neurodegenerative diseases can be characterized as disorders of protein aggregation. As a key player in cellular autophagy and the ubiquitin proteasome system, p62 may represent an effective immunohistochemical target, as well as mechanistic operator, across neurodegenerative proteinopathies. In this study, 2 novel mouse-derived monoclonal antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 raised against residues 360–380 of human p62/sequestosome-1 were characterized via immunohistochemical application upon human tissues derived from cases of C9orf72-expansion spectrum diseases, Alzheimer disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, Lewy body disease, and multiple system atrophy. 5G3 and 2A5 reliably highlighted neuronal dipeptide repeat, tau, and α-synuclein inclusions in a distribution similar to a polyclonal antibody to p62, phospho-tau antibodies 7F2 and AT8, and phospho-α-synuclein antibody 81A. However, antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 consistently stained less neuropil structures, such as tau neuropil threads and Lewy neurites, while 2A5 marked fewer glial inclusions in progressive supranuclear palsy. Both 5G3 and 2A5 revealed incidental astrocytic tau immunoreactivity in cases of Alzheimer disease and Lewy body disease with resolution superior to 7F2. Through their unique ability to highlight specific types of pathological deposits in neurodegenerative brain tissue, these novel monoclonal p62 antibodies may provide utility in both research and diagnostic efforts.

Keywords: α-Synuclein, C9orf72, Immunohistochemistry, Neurodegenerative disease, Neuropathology, p62, Tau

INTRODUCTION

A recurrent concept in human neurodegenerative disease is the aggregation and apparent propagation of pathologic protein deposits across the neuraxis (1–3). Immunohistochemistry represents a powerful and widely available technique for the identification of protein targets in this context. Robust antibodies currently exist for the immunohistochemical detection of a variety of pathologic proteins corresponding to specific diseases; antibodies for hyperphosphorylated tau and Aβ peptide now commonly serve to stage Alzheimer disease neuropathologic change (ADNC), just as antibodies for α-synuclein (αS) are used to characterize Lewy body diseases (LBD) (4, 5). However, when the diagnosis is uncertain, and the presence of several proteins must be assessed, a “one antibody, one target” approach may rapidly translate into an extensive battery of immunohistochemical stains, ultimately proving to be cost- and resource-intensive. Additionally, some neurodegenerative diseases, such as those defined by repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation, show diagnostic inclusions for which specific antibodies are not widely available on a commercial basis (6).

As a component of the cellular machinery of autophagy, the intracellular protein p62/sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1) is involved in the formation of autophagosomes, and also serves as a receptor for the delivery of ubiquitinated protein cargos into lysosomal processing (7). In a similar fashion, p62 operates within the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS), shuttling polyubiquitinated protein products toward proteasomal degradation or into the formation of stable intracellular inclusions (8). Furthermore, as a signaling molecule, p62 serves to modulate ubiquitin-mediated cytokine signals such as NF-kB, TNF-α, and caspase-8, with implications on the regulation of cellular survival and apoptosis (9, 10). Alterations of normal cellular autophagy and UPS, and the subsequent accumulation of p62-associated proteins, have been associated with a wide spectrum of human disease, including the development of liver, lung, and pancreatic tumors (11–13), metabolic diseases of liver, bone, and insulin (14–16), progressive degenerative diseases of skeletal muscle (17), and most saliently, neurodegenerative disorders of protein aggregation (18–20).

Previous studies have described the immunohistochemical colocalization of p62 to a spectrum of different protein aggregates associated with inclusions seen in neurodegenerative diseases, including the 3R/4R paired helical filament tau of Alzheimer disease (AD), the 3R tau inclusions of Pick disease, the 4R tau aggregates of progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration, globular glial tauopathy (GGT), and argyrophilic grain disease, and the neuronal and glial αS inclusions of LBD and multiple system atrophy (MSA), among others (21–24). In C9orf72-repeat expansion disorders, which encompass a spectrum of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), p62 and ubiquitin represent essential tools in detecting the neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions unique to this disease group, which are composed of dipeptide-repeat (DPR) proteins secondary to repeat-associated translation (25). Examinations into the diagnostic applicability of p62 immunohistochemistry in the setting of neurodegenerative disease have been conducted utilizing various antibody formulations, including both rabbit polyclonal and mouse monoclonal forms, as well as both N-terminus and C-terminus epitopes, and have found p62 to represent a reliable surrogate marker for highlighting these disparate proteins and related inclusions. Given its essential role in pathways related to protein degradation and cellular survival, p62 represents not only an immunohistochemical target effective across different neurodegenerative proteinopathies, but also a valuable tool for further exploring the role of autophagy and UPS between neurodegenerative proteinopathies. Presently, we examine the staining profiles of 5G3 and 2A5, 2 novel mouse monoclonal antibodies raised against residues 360–380 of human p62/sequestosome-1, upon their application to a variety of human neurodegenerative diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All animal experimental procedures were performed as approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulatory policies. Mice were housed under stable conditions with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and access to food and water ad libitum. BALB/c mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, MA).

Antibodies

The rabbit polyclonal p62/sequestosome-1 antibody (Proteintech, Roselawn, IL; catalogue number: 18420-1-AP) was utilized for immunohistochemistry and Western blotting. The mouse monoclonal anti-actin C4 antibody (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA) was utilized for Western blotting. The mouse monoclonal anti-HA.11 antibody (Covance, Princeton, NJ) was used to detect HA-p62 in Western blot analysis. AT8 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; catalogue number: MN1020) is a mouse monoclonal antibody specific toward phosphorylation sites S202 and T205 in tau (26). 7F2 is a monoclonal antibody that reacts with tau phosphorylated at T205 (27). 81A is monoclonal antibody that reacts with αS phosphorylated at S129 (28), but that can also cross-react with phosphorylated neurofilaments (29). Rabbit monoclonal antibody EP1536Y against the pSer129 epitope of αS was obtained from Abcam, Cambridge, UK (catalogue number: ab51253). TDP-43 pS409/410 (Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan; catalogue number: CAC-TIP-PTD-P02) is a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed toward phosphoserine 409/410.

Generation of Monoclonal Antibodies

A peptide was synthesized (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) containing residues 360–380 of human p62/sequestosome-1 isoform 1 along with an added N-terminal cysteine (CESEGPSSLDPSQEGPTGLKEA) and subsequently conjugated to maleimide-activated mariculture keyhold limpet hemocyanin (mcKLH; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). The conjugated peptide was used to immunize female BALB/c mice over the course of 6 weeks after which the mice were sacrificed and the spleens harvested for hybridoma fusion as described previously (27). Positive clones were screened for reactivity to the synthetic peptide using an established ELISA procedure (27).

Western Blot Detection of p62 in Cultured Cells

HEK293T cells were passaged in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented to contain 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were grown to 30%–40% confluency, after which time cells were induced to express HA-p62 cloned into the pcDNA4/TO vector (30) using calcium phosphate transfection as previously described (31). Total cell lysate was harvested in sample buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 1 mM EDTA, 40 mM DTT, 0.005% Bromophenol Blue, 0.0025% Pyronin Yellow, 1% SDS, 10% sucrose) and boiled for 10 minutes prior to SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels, with 15 μg loaded on Western blot from cell lysate. Electrophoretic transfer onto 0.45-µm nitrocellulose membranes was performed, following by incubation with block solution (5% milk in TBS). 5G3 and 2A5 primary antibodies were diluted in block solution to a concentration of 1:1000, commercially available rabbit polyclonal p62/sequestosome-1 antibody was diluted to a primary concentration of 1:2000, and all antibodies were incubated at 4°C overnight. Following washes in TBS, membranes were incubated with goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (concentration: 1:3000) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA) diluted in block solution for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was assessed using Western Lightning-Plus ECL reagents (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) followed by chemiluminescence imaging (PXi, Syngene, Frederick, MD).

Immunohistochemical Staining of p62 in Transgenic Mice

Ethanol-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue from aged homozygous M83 αS mice (M83+/+) expressing A53T human αS (32), hemizygous M83 αS mice (M83+/–) intramuscularly injected with preformed αS fibrils (33), hemizygous M20 αS mice (M20+/–) expressing WT human αS intracerebrally injected with preformed αS fibrils (34), and aged hemizygous PS19 mice (PS19+/–) expressing P301S 1N/4R human tau (35) were utilized for immunohistochemical analysis. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on brain sections from 2 mice of each type of cohort with identical procedures as described for human tissue.

Double-labeling and immunofluorescent analysis to determine colocalization of p62 with tau and αS inclusions in aged PS19 and M83 mice, respectively, was performed as described previously (36). Rabbit polyclonal anti-sera 3026 raised against T44 human tau (primary concentration: 1:1000) (27) and rabbit monoclonal antibody EP1536Y against the pSer129 epitope of αS (primary concentration: 1:1000) were utilized to detect inclusions and labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (Invitrogen, secondary antibody concentration: 1:500). Monoclonal p62 antibodies were labeled with Alexa Fluor 594 secondary antibody (Invitrogen). The sections were coverslipped with Fluoromount-G (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL) and visualized using an Olympus BX51 microscope mounted with a DP71 Olympus digital camera to capture images.

Autopsy Case Material

Human brain tissue was obtained through the University of Florida Neuromedicine Human Brain and Tissue Bank according to protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board. Postmortem diagnoses of ADNC, LBD, MSA, and PSP were made according to current guidelines and criteria proposed by (respectively) the National Institute of Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (37), the Dementia with Lewy Bodies Consortium (38), the Neuropathology Working Group on MSA (39), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (40). Five AD cases were studied that demonstrated a high degree (A3, B3, C3) of ADNC, two of which had comorbid neocortical and amygdala-predominant variants of LBD (case ID’s: AD2 and AD3, respectively). Five LBD cases were studied that included 4 cases of “neocortical (diffuse)” LBD (case ID’s: LBD1, LBD2, LBD3, and LBD5) and one case of “limbic (transitional)” LBD (case ID: LBD4). Of these LBD cases, 4 demonstrated comorbid ADNC (case ID’s: LBD1, LBD2, LBD4, and LBD5), one demonstrated hippocampal sclerosis (LBD2), and one exhibited findings consistent with GGT (case ID: LBD3). Five MSA cases were studied that included the 2 major pathological subtypes: Striato-nigral degeneration (“MSA-P”—3 cases, ID’s: MSA2, MSA4, MSA5) and olivo-ponto-cerebellar atrophy (“MSA-C”—1 case, ID MSA3), with one case showing findings consistent with both subtypes (case ID: MSA1). Two MSA cases demonstrated comorbid ADNC (case ID’s: MSA2 and MSA3). Five cases of PSP were studied, 2 of which contained comorbidity with ADNC (case ID’s: PSP3 and PSP5), and 2 of which had the comorbidity of primary age-related tauopathy (“PART”; case ID: PSP1 and PSP4).

Tissues derived from C9orf72-repeat expansion ALS and FTLD spectrum diseases were obtained from the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. Cases examined included 3 cases of ALS (case ID’s: C9orf72-1, C9orf72-2, C9orf72-6), 1 case of FTLD (case ID’s: C9orf72-5), and 2 cases of FTLD-MND (case ID’s: C9orf72-3, C9orf72-4). One case of FTLD-MND (case ID: C9orf72-3) demonstrated copathologic hippocampal sclerosis (Table).

TABLE.

Patient Demographics of Cases Studied

| Sex | Age at Death | PMI | Primary Diagnosis | Copathology (If Present) | Brain Area Studied | Braak Stage | Thal Phase | CERAD Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | |||||||||

| AD1 | Male | 64 | 6 | ADNC, high | Amygdala, hippocampus | VI | 5 | 3 | |

| AD2 | Male | 80 | 21 | ADNC, high | LBD (neocortical) | Amygdala, hippocampus | VI | 4 | 3 |

| AD3 | Male | 64 | 3 | ADNC, high | LBD (amygdala-predominant) | Amygdala, hippocampus | V | 5 | 3 |

| AD4 | Male | 78 | 20 | ADNC, high | Amygdala, hippocampus | V | 4 | 3 | |

| AD5 | Male | 83 | 7 | ADNC, high | Amygdala, hippocampus | VI | 4 | 3 | |

| PSP | |||||||||

| PSP1 | Female | 72 | 8 | PSP | PART | Striatum | II | 0 | 0 |

| PSP2 | Female | 63 | 14 | PSP | Striatum | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| PSP3 | Male | 77 | 6 | PSP | ADNC, low | Striatum | II | 3 | 2 |

| PSP4 | Male | 78 | 23 | PSP | PART | Striatum | II | 0 | 0 |

| PSP5 | Male | 72 | 16 | PSP | ADNC, intermediate | Pons | III | 2 | 2 |

| LBD | |||||||||

| LBD1 | Male | 62 | 10 | LBD (neocortical) | ADNC, low | Amygdala, midbrain | II | 1 | 1 |

| LBD2 | Female | 88 | 2 | LBD (neocortical) | ADNC, intermediate HS | Amygdala, midbrain | III | 4 | 3 |

| LBD3 | Male | 80 | 4 | LBD (neocortical) | GGT | Amygdala, midbrain | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| LBD4 | Male | 80 | 10 | LBD (transitional) | ADNC, intermediate | Amygdala, midbrain | III | 3 | 2 |

| LBD5 | Male | 68 | 39 | LBD (neocortical) | ADNC, intermediate | Amygdala, midbrain | V | 3 | 3 |

| MSA | |||||||||

| MSA1 | Female | 66 | 22 | MSA -P and -C | Pons, cerebellum | I | 0 | 0 | |

| MSA2 | Female | 68 | 25 | MSA-P | ADNC, low | Pons, cerebellum | I | 3 | 2 |

| MSA3 | Male | 71 | 4 | MSA-C | ADNC, low | Pons, cerebellum | I | 3 | 1 |

| MSA4 | Male | 77 | 18 | MSA-P | Pons, cerebellum | II | 0 | 0 | |

| MSA5 | Female | 60 | 6 | MSA-P | Pons, cerebellum | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| C9orf72 | |||||||||

| C9orf72-1 | Male | 59 | 35 | ALS | Hippocampus, cerebellum | II–III | 1 | – | |

| C9orf72-2 | Female | 70 | 8 | ALS | Hippocampus, cerebellum | 0 | 3 | – | |

| C9orf72-3 | Male | 61 | 23 | FTLD-MND | HS | Hippocampus, cerebellum | III | 1 | – |

| C9orf72-4 | Female | 61 | 14 | FTLD-MND | Hippocampus, cerebellum | II | 2 | – | |

| C9orf72-5 | Female | 67 | 19 | FTLD-MDN | Hippocampus, cerebellum | III | 1 | – | |

| C9orf72-6 | Female | 62 | 38 | ALS | cerebellum | II | 0 | – |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; ADNC, Alzheimer disease neuropathologic change; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; LBD, Lewy body disease; MSA, multiple system atrophy; PART, primary age-related tauopathy; GGT, globular glial tauopathy; HS, hippocampal sclerosis; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; MND, motor neuron disease; PMI, postmortem interval.

Immunohistochemical Staining of Neuropathologic Human Tissue

To morphologically assess the immunoreactive profile of antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 in neurodegenerative human tissue, these novel p62 antibodies were applied to selected brain regions of pathologically confirmed cases of AD (hippocampus and amygdala), LBD (midbrain and amygdala), MSA (pons and cerebellum), PSP (striatum and pons), and C9orf72-repeat expansion spectrum disorders (hippocampus and cerebellum). One case of C9orf72-repeat expansion disease (C9orf72-6) was utilized specifically to examine the effect of formic acid treatment on antigen retrieval efficacy, with only cerebellum of this case examined; this case was excluded from semiquantitative analysis. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized by xylene immersion, with subsequent sequential rehydration via graded ethanol solutions (100%, 90%, 70%). Sections underwent heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) via steam bath in a 0.05% Tween-20 solution for 60 minutes. A subset of tissues of each disease type were additionally subjected to a 20-minute immersion in 70% formic acid after HIER. Twenty-minute immersion in a solution of 1.5% hydrogen peroxide, 0.005% Triton-X-100, and phosphate-buffered saline was conducted to achieve quenching of endogenous tissue peroxidase activity, with subsequent water rinse. Sections were blocked with 2% FBS/0.1 M Tris (pH 7.6) and incubated overnight with primary antibody at 4°C. For pre-absorption blocking studies, the primary antibody was pre-incubated with the peptide that was used for immunization at 1 μg/mL for 3 hours in 2% FBS/0.1 M Tris (pH 7.6) at room temperature prior to applying the antibody to a section of amygdala of a case of AD (AD3). Following washes with 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.6), biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody or biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody diluted in 2% FBS/0.1 M Tris (pH 7.6) was applied to tissue for 1 hour (secondary antibody concentrations: 1:3000). Sections were then washed with 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.6) and incubated with streptavidin-conjugated HRP (VECTASTAIN ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) diluted in 2% FBS/0.1 M Tris, pH 7.6 for 1 hour. Sections were again washed with 0.1 M (pH 7.6) and then were exposed to 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB kit; KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) to initiate development. Reactions were halted by immersing sections in 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.6). Mayer’s hematoxylin served as a counterstain (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Sections were subsequently dehydrated via an ascending ethanol series (70%, 90%, 100%) and xylenes, and were cover-slipped using cytoseal (Thermo Scientific).

In all tissues, the immunoreactive profile of 5G3 (primary concentration: 1:1000) and 2A5 (primary concentration: 1:1000) were then compared with that of a commercially available rabbit polyclonal p62/sequestosome-1 antibody (primary concentration: 1:2000). A representative case of each disease type was selected, and in one area of each representative case, the immunoreactive profiles of 5G3, 2A5, and commercial polyclonal p62 were compared with that of phospho-tau (7F2 in AD and GGT with primary concentration: 1:10 000, AT8 in PSP with primary concentration: 1:1000), phospho-αS 81A (primary concentration: 1:3000), and TDP-43 pS409/410 (Cosmo Bio, catalogue number: CAC-TIP-PTD-P02, primary concentration: 1:1000). The abundance of immunoreactive inclusions as elucidated by each antibody was observed and semiquantitatively assessed (0 = none, 1 = few, 2 = moderate, 3 = frequent) by one observer utilizing an Olympus CX31 microscope (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) and confirmed by a second. Instances in which the semiquantitative pathologic burden was assessed as intermediate between categories was designated as such, for example, “1.5” for instances in which more than “few” inclusions were present but did not reach threshold for “moderate” as assessed by observers.

RESULTS

Western Blot Detection of p62 in Cultured Cells and Specificity of New p62 Monoclonal Antibodies

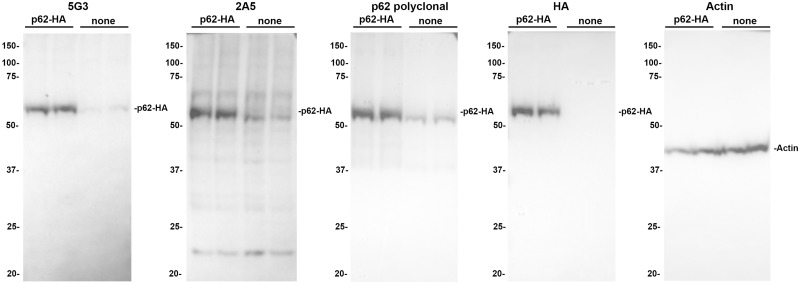

To facilitate the detection of p62, multiple monoclonal antibodies were produced against residues 360–380 of the p62 protein, which were subsequently screened through their ability to detect HA tagged p62 transiently expressed in cultured HEK293T cells (Fig. 1). Clones 5G3 and 2A5 were efficacious in detecting p62, as the intensity of the ∼62-kDa band corresponding to p62 was greatly increased in cells overexpressing the HA-tagged protein. The 2A5 clone satisfactorily detects p62, however minor nonspecific bands are present particularly at ∼22 kDa. Comparatively, the only band detected by the 5G3 clone was identical to that detected by the anti-HA antibody, demonstrating the specificity of the 5G3 clone for p62. Indeed, the specificity of the 5G3 clone is equal to or better than that of the commercial polyclonal antibody, indicating that this monoclonal antibody only detects its intended target.

FIGURE 1.

Western blot characterization of p62 monoclonal antibodies 5G3 and 2A5. HEK293T cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing HA-tagged p62 and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting as described in Material and Methods. The intensity of the ∼62-kDa band corresponding to p62 was greatly increased in cells expressing the HA-tagged protein, indicating competent target detection. The 5G3 clone demonstrated a protein banding pattern identical to that detected by the anti-HA antibody, indicating robust specificity for p62. The 2A5 clone detected nonspecific bands (most pronounced at ∼22 kDa) in addition to p62. A blot for actin is shown as a loading control. The mobility of molecular mass markers is shown on the left of each blot.

Performance of Novel p62 Antibodies in Detecting DPR Inclusions of C9orf72-Repeat Expansion Disease

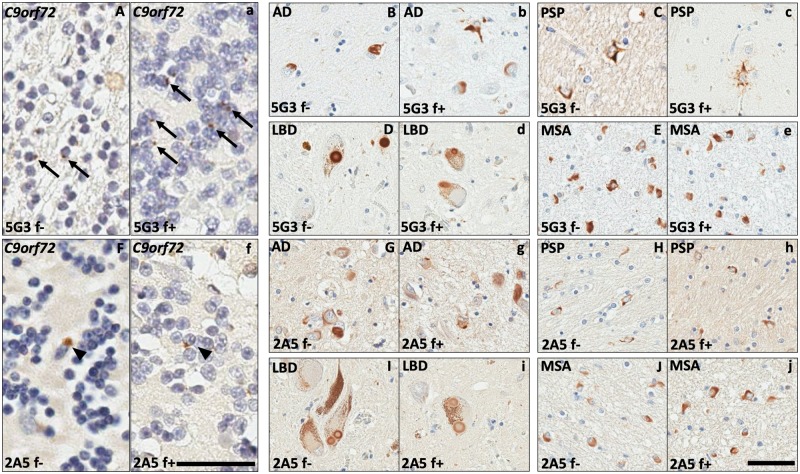

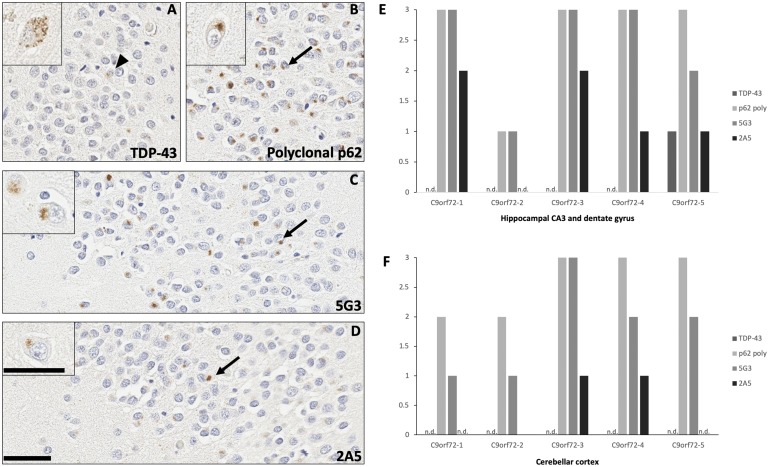

In human ALS, FTLD, and FTLD-MND tissues, 5G3 and 2A5 capably highlighted the stellate neuronal DPR inclusions classic of C9orf72-repeat expansion spectrum disorders. Inclusions were identified by these antibodies in neurons of the cerebellar molecular layer and granular cell layer (Fig. 2A, F), as well as hippocampal complex neurons of the dentate gyrus and areas CA3-CA4 (Fig. 3C, D). While 5G3 detected slightly fewer DPR inclusions than polyclonal p62, antibody 2A5 detected a markedly lesser number of inclusions as compared with its counterparts (Fig. 3E, F). TDP-43 immunostaining of these regions highlighted scattered neuronal inclusions in one case (C9orf72-5); however, TDP-43-immunoreactive inclusions were morphologically distinct from the stellate DPR inclusions revealed by 5G3, 2A5, and polyclonal p62 (Fig. 3A–D). Formic acid antigen retrieval yielded a modest increase in the number of inclusions detected by 5G3 within the cerebellar granular cell layer; however, no significant increase in inclusions detected by 2A5 was noted after formic acid treatment (Fig. 2A-a, B-b). Postmortem interval did not modulate immunoreactivity across tissues.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of immunoreactive inclusions identified across neurodegenerative diseases with and without formic acid-enhanced antigen retrieval. Antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 detected neuronal DPR inclusions in C9orf72-expansion spectrum diseases (A, F), neuronal NFTs in AD (B, G), tufted astrocytes in PSP (C, H), Lewy bodies in LBD (D, I), and GCIs in MSA (E, J). Incorporation of formic acid into antigen retrieval mildly increased the numbers of DPR inclusions detected by 5G3 in the cerebellar granular cell layer of C9orf72-expansion tissues (a; arrows). Formic acid treatment did not increase the number of C9orf72-expansion DPR NCIs detected by 2A5 (f; arrowheads). No significant increase in the number of inclusions, nor background neuropil structures, was appreciated for either antibody upon application of formic acid onto AD, PSP, LBD, and MSA tissues (b–e and g–j). Without formic acid treatment: “f–.” With formic acid treatment: “f+.” Left bar = 100 μm, corresponding to A, a, F, and f. Right bar = 60 μm, corresponding to B–E, b–e, G–J, and g–j.

FIGURE 3.

Immunohistochemical and semiquantitative evaluation of stellate dipeptide repeat (DPR) inclusions across C9orf72 repeat expansion cases. Stellate DPR inclusions were labeled by 5G3 and 2A5 in the neurons of the hippocampal dentate gyrus (C, D; arrows), as well as neurons of areas CA3-4 (C, D; insets). In one case of C9orf72-repeat expansion FTLD (C9orf72-5), TDP-43 immunoreactive inclusions were identified in rare neurons of hippocampal area CA4 and dentate gyrus (A; arrowhead), as well as granulovacuolar degeneration-like cytoplasmic pathology in neurons of area CA3 (A; inset), but these findings were morphologically dissimilar from the stellate DPR inclusions detected by 5G3, 2A5, and polyclonal p62 (B–D). Semiquantitative analysis of burden showing that 5G3 detected the stellate DPR inclusions of C9orf72 repeat expansion cases at mildly lesser numbers than polyclonal p62 (E, F). Antibody 2A5 detected a markedly lower number of DPR than its counterparts, particularly in the cerebellar granular layer (E, F). As expected, DPR were nonreactive for TDP-43 antibody. Background TDP-43 immunoreactive inclusions were noted in one case (C9orf72-5) in the neurons of the hippocampal endplate (E), which were morphologically dissimilar from those detected by p62 antibodies. Not detected: “n.d.” Bar = 50 μm; bar for high-magnification insets = 100 μm.

Performance of Novel p62 Antibodies in Detecting Tau Inclusions

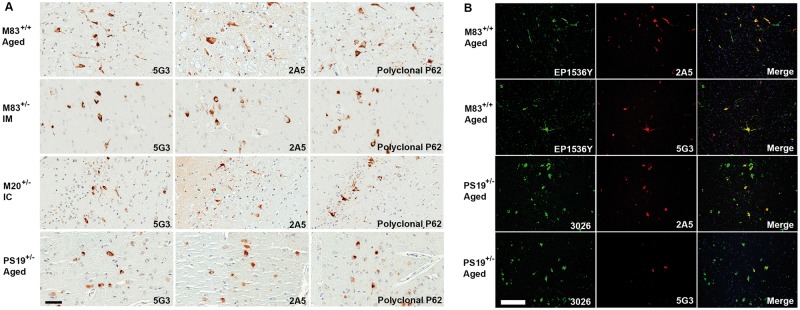

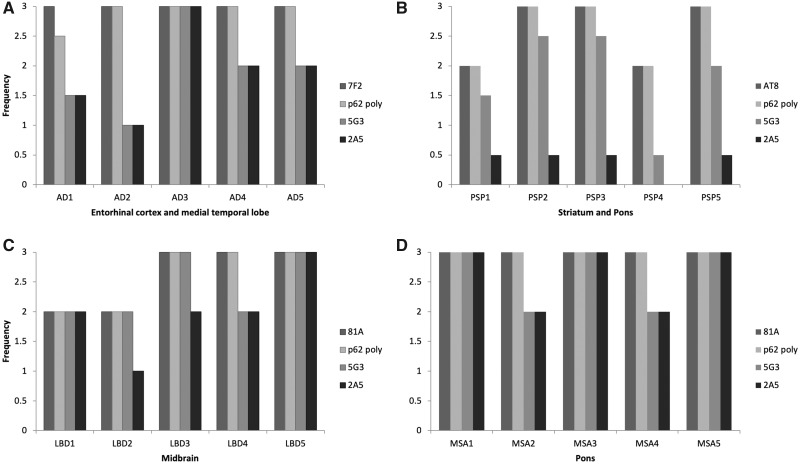

In the PS19+/– transgenic mouse model of tauopathy antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 demonstrated comparable sensitivity to rabbit polyclonal commercial p62 in immunohistochemically in detecting tau neuronal inclusions (Fig. 4A) with tau inclusion colocalization demonstrated by double-label immunofluorescence with tau-specific antibody (anti-sera 3026) (Fig. 4B). In human AD tissues, antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 consistently showed immunohistochemical reactivity for tau inclusions in the form of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) (Fig. 2B, G). By semiquantitative analysis, 5G3 and 2A5 exhibited a tendency to label a lesser number of NFTs as compared with polyclonal p62 and anti-phospho tau antibody 7F2 in sections of hippocampal complex, entorhinal cortex, and adjacent medial temporal lobe neocortex (Fig. 5A). Despite differences in NFT burden highlighted, no significant differences in the topographic distribution of inclusions were identified; in AD sections of medial temporal lobe cortex, NFTs were labeled with anti-phospho tau antibody 7F2, polyclonal p62, 5G3 and 2A5 with a predominant distribution along cortical layers III–VI. While 7F2 antibody robustly detected Aβ amyloid plaque-associated dystrophic neurites and neuropil threads, these were only infrequently detected by 5G3, and minimally-to-not detected by 2A5 (Fig. 2B, G). No significant increase in NFT detection was noted of 5G3 and 2A5 upon application of formic acid treatment (Fig. 2b, g).

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of 5G3 and 2A5 antibodies in mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases by immunohistochemistry and double-label immunofluorescence. Immunohistochemistry: Antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 demonstrated reactivity for tau and αS deposits nearly comparable to that of polyclonal p62 in various mouse models of tauopathies or synucleinopathies, respectively. Representative images of brain tissue from aging PS19+/– tau or M83+/+ αS transgenic mice as well as prion-like seeded M83+/– and M20+/– αS transgenic mice. IM are M83+/– mice that were intramuscularly inoculated with αS fibrillar seeds, while IC are M20+/– mice that received intracerebral αS fibrillar seeds to induce the progressive spread of αS inclusion pathology. All images from M83 or M20 mice were captured from brainstem, and all PS19 images were captured from midbrain. Immunofluorescence: Double-label immunofluorescence incorporating antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 showed the ability to detect discrete intraneuronal αS and tau inclusions in M83 and PS19+/– transgenic mouse tissues, with colocalization of signal with αS (antibody EP1536Y; EP) and tau (3026) specific antibodies, respectively. Both 5G3 and 2A5 were noted to detect less small-structure neuropil pathology as compared with αS- and tau-specific antibodies. Bar = 50 μm.

FIGURE 5.

Semiquantitative comparative analysis of inclusion pathology reactive to 5G3 and 2A5 compared with polyclonal p62 and antibodies specific for tau or αS. As compared with antiphospho tau antibody 7F2 and polyclonal p62 antibody, both 5G3 and 2A5 demonstrated a mildly lesser ability to highlight NFTs in the entorhinal cortex and medial temporal lobe of AD tissues (A). In PSP tissues, 2A5 consistently highlighted minimal numbers of tufted astrocytes; while 5G3 reliably highlighted tufted astrocytes, it consistently highlighted lesser numbers as compared with antiphospho tau antibody AT8 or polyclonal p62 antibody (B). In LBD midbrain tissues, 5G3 demonstrated nearly comparable ability in detecting LB inclusions as antiphospho αS antibody 81A and polyclonal p62 antibody; 2A5 also detected LB inclusions, but at mildly lesser numbers than its counterparts (C). In MSA pontine tissue, both 5G3 and 2A5 showed a nearly comparable ability to detect GCI inclusions as that of antiphospho αS antibody 81A and polyclonal p62 antibody (D).

In human PSP tissues, antibody 5G3 consistently showed reactivity for glial tau inclusions in the form of tufted astrocytes and oligodengroglial coiled bodies, as well as neuronal tau inclusions in the form of globose NFTs (Fig. 2C, H). 5G3 labeled these inclusions at a mildly lesser frequency than polyclonal p62 and anti-phospho tau antibody AT8, the former and latter of which demonstrated comparable sensitivity to each other. In contrast, antibody 2A5 highlighted comparatively few neuronal globose NFTs, scant numbers of oligodendroglial coiled bodies, and few tufted astrocytes (Fig. 5B). No significant alteration in the amount of PSP-related tau inclusions detected by 5G3 and 2A5 was appreciated upon application of formic acid to tissue (Fig. 2c, h).

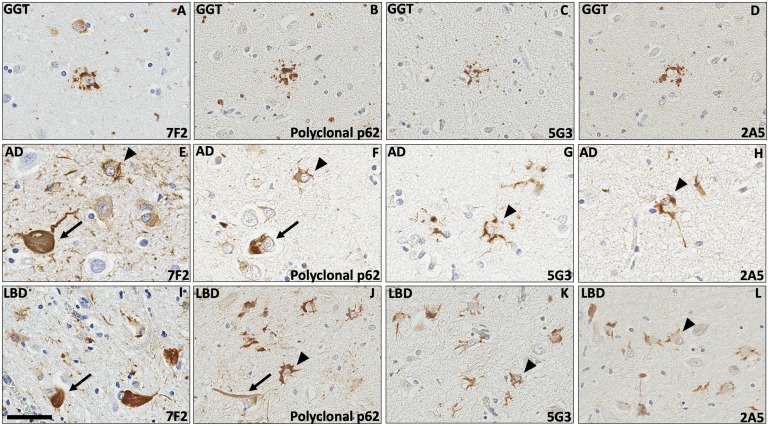

In LBD case 3, concomitant GGT inclusions were present in sections of amygdala and midbrain. Antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 showed reactivity for globular glial inclusions in the form of both globular astrocytic inclusions (GAIs) (Fig. 6A–D) and globular oligodendroglial inclusions (GOIs) (data not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Astrocytic pathology detected by 5G3 and 2A5 antibodies. In a case of LBD with comorbid globular glial tauopathy ([GGT]; LBD3), the GAIs detected by 7F2 and polyclonal p62 (A, B) were highlighted in a comparable fashion by 5G3 and 2A5 (C, D). In the amygdalae of one case of AD (AD1; E–H) and one case of LBD (LBD5; I–L), antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 revealed astrocytic stellate morphology and fine cytoplasmic staining concentrating around the periphery of cell soma and proximal processes (arrowheads). While polyclonal p62 (F, J) and antiphospho tau antibody 7F2 (E, I) also highlighted these astrocytes, 5G3 (G, K) and 2A5 (H, L) offered comparatively sharper resolution for the visualization of astrocytic changes, as these novel antibodies highlighted lesser numbers of neuronal NFTs (arrows) and minimal background neuropil structures. Bar = 60 μm.

Review of human neurodegenerative tissue additionally elucidated p62-reactive findings in 2 cases, AD1 and LBD5, which did not morphologically correspond to classic pathologies in AD or LBD, respectively. In both cases, these findings manifested as apparent astrocytic alterations. In AD1, polyclonal p62, 5G3, and 2A5 antibodies similarly highlighted stellate astrocytes in the amygdala with similar fine to globular cytoplasmic staining (Fig. 6F–H). In LBD5, the amygdala contained abundant astrocytes, of which polyclonal p62, 5G3, and 2A5 antibodies revealed a stellate morphology via fine cytoplasmic staining which concentrated in a globular fashion around the periphery of cell bodies and in proximal processes (Fig. 6J–L). The astrocytic findings of both AD1 and LBD5 demonstrated reactivity for 7F2 (Fig. 6E, I).

As a negative tissue control for antibody staining of tau inclusions, 5G3 and 2A5 were applied to sections of cerebellum in a case of AD, with polyclonal p62 and 7F2 serving as reference standards. Both 5G3 and 2A5 did not highlight inclusions, recapitulating the lack of tissue reactivity observed of polyclonal p62 and 7F2 (Supplementary DataFig. S1A–D). Across tissues, postmortem interval did not impact immunoreactivity for tau inclusions. Furthermore, pre-incubation of antibody 5G3 with the peptide corresponding to epitope 360–380 of p62 prior to immunohistochemical staining demonstrated complete blocking of immunoreactivity within tissue also demonstrating antibody specificity (Supplementary DataFig. S2A and B).

Performance of Novel p62 Antibodies in Detecting α-Synuclein Inclusions

In M83+/+ aged transgenic mice, antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 demonstrated a comparable sensitivity to polyclonal p62 for detecting αS neuronal deposits and neuropil neurites (Fig. 4A). In M83+/– αS transgenic mice CNS inclusions were induced via a prion-like mechanism following intramuscularly injected with preformed αS fibrils and neuroinvasion (33). While 5G3 and 2A5 demonstrated a similar sensitivity in detecting αS neuronal deposits and neuropil neurites, staining with polyclonal p62 antibody was observed to highlight a greater number of deposits in the same areas. In M20+/– αS transgenic mice where αS CNS deposits were induced by the direct brain injection of preformed αS fibrils (34), comparable sensitivity between antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 in detecting neuronal deposits and neuropil threads was observed, albeit at mildly lesser numbers than with polyclonal p62 antibody. Across all p62 antibodies, both aging and prion-like muscle-injected M83 αS mice demonstrated inclusions largely concentrated in brainstem and midbrain, with sparse few neuronal deposits identified in basal forebrain structures. In the brain-seeded M20+/– αS mice, the spread of αS inclusions demonstrated the greatest burden of deposits in midbrain, hippocampus, and more rostrally in the striatum and overlying cortex. Double-label immunofluorescence of mouse tissue confirmed colocalization of p62 signal with that of αS-specific antibody (EP1536Y) (Fig. 4B).

In human LBD tissue, antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 demonstrated consistent reactivity for αS inclusions in the form of intracellular and parenchymal Lewy bodies (LBs) (Fig. 2D, I). By semiquantitative analysis, 5G3 and 2A5 highlighted a mildly lesser number LB inclusions as compared with anti-phospho αS antibody 81A and commercial rabbit polyclonal p62 (Fig. 5C). 5G3 and 2A5 exhibited substantially lesser ability to detect Lewy neurites (LNs), with 5G3 highlighting them infrequently, and 2A5 minimally to not at all (Fig. 2D, I). No significant change in LB and LN deposits detected by 5G2 and 2A5 was noted after additional antigen retrieval with formic acid (Fig. 2d, i).

In human MSA tissues, antibodies 5G3 and 2A5 consistently showed reactivity for αS inclusions in the form of glial cytoplasmic inclusions ([GCIs]; “Papp-Lantos inclusions”; Fig. 2E, J). By semiquantitative analysis, 5G3 and 2A5 highlighted a comparable number of GCIs as compared with anti-phospho αS antibody 81A and commercial rabbit polyclonal p62, in both pons and cerebellum (Fig. 5D). No significant change in GCIs detected by 5G3 and 2A5 was noted upon pretreatment with formic acid (Fig. 2e, j).

In a case of LBD with copathologic ADNC (case LBD5), 5G3 and 2A5 were applied to a section of primary visual neocortex to assess their ability to detect inclusions in tissue bearing multiple neurodegenerative processes. Polyclonal p62 and 81A served as comparative standards. Both 5G3 and 2A5 were able to detect both LB and NFT inclusions. As detected by 5G3, 2A5, and polyclonal p62 antibodies, LB and NFT inclusions were frequently able to be discriminated from each other by morphologic means (Supplementary DataFig. S3B–D).

DISCUSSION

We describe the generation and characterization of 2 novel mouse monoclonal antibodies with specificity for residues 360–380 of human p62/SQSTM1, named 5G3 and 2A5. Other mouse-derived monoclonal antibodies targeting p62 that are currently commercially available show specificity for a variety of epitopes, ranging from large segments of the amino acid map (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO; clone 5H7E2 catalogue number: NBP2-23490, OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD; clone OTI6A7 catalogue number: TA502239, MBL International, Des Plaines, IL; clone 5F2 catalogue number: M162-3B), small segments near the N-terminus (Boster Bio, Pleasanton, CA; clone 3H11 catalogue number: M00300-1) and midsection of the peptide (BioLegend, San Diego, CA; clone 1B5.H9 catalogue number: 814802), to phosphorylated amino acid sites (MBL International; clone 5D5 catalogue number: M217-3). However, the current roster of commercially available antibodies does not include a clone with specificity for the epitope coded by residues 360–380. This epitope corresponds to a region located between 2 highly functional domains in the carboxy-terminal of the protein, keap-1 interacting region (KIR) and ubiquitin associated domain (UBA), the latter of which is implicated in the association of p62 with ubiquitinated products and autophagy at large (41). Application of these novel antibodies with specificity to this functionally relevant region yielded unique variations in specificity and sensitivity for inclusions across neurodegenerative proteinopathies.

In the context of C9orf72-repeat expansion spectrum diseases, both 5G3 and 2A5 successfully detected stellate DPR inclusions within neurons of the cerebellar granular cell and molecular layer, as well as hippocampal areas CA3-CA4 and dentate gyrus. These stellate DPR inclusions were not detected by phospho-TDP-43, compatible with the immunophenotypic profile of the unique inclusions described of C9orf72-expansion disease (42, 43). While competent in detecting large cytoplasmic tau- and αS-based inclusions, both 5G3 and 2A5 demonstrated a limited ability to stain small structures in the neuropil, such as tau-reactive neuropil threads and LNs. These findings are in line with previous reports on the reactivity profile of other p62 antibody clones, which additionally also found p62 to be less reactive with other ubiquitin-bound neuropil deposits, such as Aβ amyloid peptide plaques and neuropil grains (44). The performance of 5G3 and 2A5 generally fared better with regard to neuronal intracytoplasmic inclusions, albeit demonstrating a modest reduction in the number of inclusions identified in comparison to tau and αS-specific antibodies. This trend was specifically observed of neuronal NFTs in ADNC, and neuronal LBs in LBD.

One of the greatest strengths of 5G3 and 2A5 proved to be the ability to identify glial inclusions across most proteinopathy types. Both 5G3 and 2A5 demonstrated a robust ability to detect GCIs in MSA, comparable to that of anti-αS antibody 81A. In a case of GGT, both 5G3 and 2A5 highlighted GAI and GOI with an efficacy similar to a tau-specific antibody. Additionally, given their reduced staining of background neuropil structures, these novel monoclonal antibodies allowed for the expeditious detection of tau-reactive astrocytes, a finding detected in the amygdalae of a case of ADNC and a case of LBD. This latter feature may prove useful in disease processes in which tau-reactive astrocytes—a subtle finding often easily overlooked through the lens of a tau-specific antibody amid a dense background of neuropil threads—represent a significant component, such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and aging-related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG) (45–47). It must be noted that cases of PSP represented an exception to this pattern, as both 5G3 and 2A5 demonstrated a limited ability to detect the 4R tau inclusions of tufted astrocytes and oligodendroglial coiled bodies, even after enhanced antigen retrieval via tissue pretreatment with formic acid.

The nuances of 5G3 and 2A5’s staining profiles highlight interesting questions regarding the functional contribution of p62 in protein aggregation disorders. Immunoreactivity for p62 ultimately signifies a secondary modification to proteins earmarked for autophagy or proteosomal processing. Examination of what aspects of neurodegenerative protein aggregation are marked for degradation—and what components are not—may provide insight into cellular responses and adaptations to neurodegenerative proteinopathy. Particularly noteworthy is the general lack of reactivity of p62 for neuropil accumulations, such as LNs, neuropil threads, and plaque-associated dystrophic neurites, even after tissue pretreatment with formic acid. This feature was observed in both immunohistochemical as well as double-label immunofluorescence application of p62 antibodies, across neurodegenerative disease types. A possible hypothesis is that while large, intracytoplasmic deposits are labeled and sequestered for attempted degradation, neuropil accumulations are less incorporated into the cellular processes of autophagy and proteosomal degradation. This nuance is particularly interesting given that previous studies have suggested that p62 is incorporated into tau NFTs early in the disease course of AD, with p62 reactivity identified in asymptomatic patients exhibiting Braak stage I tau inclusions (48). These findings present an interesting mechanistic possibility, given that dystrophic neurites constitute part of the neuritic plaque, a structure considered biologically relevant to AD (49–52). Insights into the role of autophagy and UPS within other contexts, such as PSP, GGT, MSA, CTE, and normal brain aging, can be gleaned in observing its immunohistochemical distribution as highlighted by p62 antibodies with different epitope specificities.

Our findings support the utility of 5G3 and 2A5 as diagnostic tools for C9orf72-related ALS and FTLD, and potentially other diseases characterized by RAN translation. The diagnosis of C9orf72 ALS/FTLD commonly relies on the application of surrogate markers like p62, as specific antibodies for the disease-defining DPR inclusions are not widely available on a commercial basis. Antibodies for p62 find a similar use in the diagnosis of other repeat-expansion disorders of RAN translation, which include Huntington disease, fragile X syndrome, myotonic dystrophy types 1 and 2 (DM1, DM2), and spinocerebellar ataxias 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 17, 31, and 36 (6, 53). In such diseases, p62 is used to detect the protein products of RAN translation; in Huntington disease, these present as neuronal inclusions and neuropil threads, while in spinocerebellar ataxias, protein products may present as intranuclear neuronal inclusions (54–56). Ubiquitin has also historically been used as tool for detecting such inclusions. Both p62 and ubiquitin represent components of cellular UPS, and as such, can be used in a similar capacity to highlight aberrant protein accumulation that have been labeled for degradation. However, ubiquitin antibodies consistently exhibit extensive reactivity within background tissue, and have been documented to show lower intensity labeling of diagnostic inclusions as compared with p62 (22). By virtue of its reduced immunoreactivity for nonspecific background structures, p62 provides a superior tool for the identification of inclusions for which specific antibodies are not currently widely available.

Conclusion

We introduce 2 novel mouse monoclonal antibodies for p62, 5G3 and 2A5, raised against residues 360–380 of human p62. These antibodies have demonstrated a unique ability to highlight specific types of deposits across neurodegenerative disease types. In addition to serving as tools for investigations into the role of p62 in protein aggregation disorders, these antibodies may find practical use as tools for diagnosing C9orf72-repeat expansion disorders, as well as potentially other repeat-expansion disorders for which protein-specific antibodies are not readily available.

Supplementary Material

These studies were supported by grants NS089622 and AG047266 from the National Institutes of Health. ZAS received support from F30AG063446. Tissue samples were supplied by the University of Florida Neuromedicine Human Brain Tissue Bank and the Mayo Clinic ADRC (P30 AG062677).

The authors have no duality or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ross CA, Poirier MA.. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat Med 2004;10:S10–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Golde TE, Borchelt DR, Giasson BI, et al. Thinking laterally about neurodegenerative proteinopathies. J Clin Invest 2013;123:1847–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spires-Jones TL, Attems J, Thal DR.. Interactions of pathological proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol 2017;134:187–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, et al. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 2006;112:389–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beach TG, White CL, Hamilton RL, et al. Evaluation of α-synuclein immunohistochemical methods used by invited experts. Acta Neuropathol 2008;116:277–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Banez-Coronel M, Ranum LPW.. Repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation: Insights from pathology. Lab Invest 2019;99:929–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Komatsu M, Kageyama S, Ichimura Y.. Invited review p62/SQSTM1/A170: Physiology and pathology. Pharmacol Res 2012;66:457–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wooten MW, Hu X, Babu JR, et al. Signaling, polyubiquitination, trafficking, and inclusions: Sequestosome 1/p62’s role in neurodegenerative disease. J Biomed Biotechnol 2006;2006:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jin Z, Li Y, Pitti R, et al. Cullin3-based polyubiquitination and p62-dependent aggregation of caspase-8 mediate extrinsic apoptosis signaling. Cell 2009;137:721–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT, Wooten MW.. Signal integration and diversification through the p62 scaffold protein. Trends Biochem Sci 2007;32:95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takamura A, Komatsu M, Hara T, et al. Autophagy-deficient mice develop multiple liver tumors. Genes Dev 2011;25:795–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duran A, Linares JF, Galvez AS, et al. The signaling adaptor p62 is an important NF-κB mediator in tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2008;13:343–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ling J, Kang Y, Zhao R, et al. KrasG12D-induced IKK2/β/NF-κB activation by IL-1α and p62 feedforward loops is required for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012;21:105–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Denk H, Stumptner C, Zatloukal K.. Mallory bodies revisited. J Hepatol 2000;32:689–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Layfield R, Cavey JR, Najat D, et al. p62 mutations, ubiquitin recognition and Paget’s disease of bone. Biochem Soc Trans 2006;34:735–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodriguez A, Durán A, Selloum M, et al. Mature-onset obesity and insulin resistance in mice deficient in the signaling adapter p62. Cell Metab 2006;3:211–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nogalska A, Terracciano C, D’Agostino C, et al. p62/SQSTM1 is overexpressed and prominently accumulated in inclusions of sporadic inclusion-body myositis muscle fibers, and can help differentiating it from polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Acta Neuropathol 2009;118:407–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wong E, Maria Cuervo A.. Autophagy gone awry in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci 2010;13:805–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chu CT. Mechanisms of selective autophagy and mitophagy: Implications for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis 2019;122:23–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zatloukal K, Stumptner C, Fuchsbichler A, et al. p62 is a common component of cytoplasmic inclusions in protein aggregation diseases. Am J Pathol 2002;160:255–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuusisto E, Parkkinen L, Alafuzoff I.. Morphogenesis of Lewy bodies: Dissimilar incorporation of α-synuclein, ubiquitin, and p62. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2003;62:1241–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuusisto E, Kauppinen T, Alafuzoff I.. Use of p62/SQSTM1 antibodies for neuropathological diagnosis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2008;34:169–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arai T, Nonaka T, Hasegawa M, et al. Neuronal and glial inclusions in frontotemporal dementia with or without motor neuron disease are immunopositive for p62. Neurosci Lett 2003;342:41–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scott IS, Lowe JS.. The ubiquitin-binding protein p62 identifies argyrophilic grain pathology with greater sensitivity than conventional silver stains. Acta Neuropathol 2007;113:417–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mackenzie IRA, Frick P, Neumann M.. The neuropathology associated with repeat expansions in the C9ORF72 gene. Acta Neuropathol 2014;127:347–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goedert M, Jakes R, Vanmechelen E.. Monoclonal antibody AT8 recognises tau protein phosphorylated at both serine 202 and threonine 205. Neurosci Lett 1995;189:167–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Strang KH, Goodwin MS, Riffe C, et al. Generation and characterization of new monoclonal antibodies targeting the PHF1 and AT8 epitopes on human tau. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2017;5:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Waxman EA, Giasson BI.. Specificity and regulation of casein kinase-mediated phosphorylation of α-synuclein. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2008;67:402–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sacino AN, Brooks M, Thomas MA, et al. Amyloidogenic α-synuclein seeds do not invariably induce rapid, widespread pathology in mice. Acta Neuropathol 2014;127:645–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fan W, Tang Z, Chen D, et al. Keap1 facilitates p62-mediated ubiquitin aggregate clearance via autophagy. Autophagy 2010;6:614–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sorrentino ZA, Vijayaraghavan N, Gorion K-M, et al. Physiological C-terminal truncation of α-synuclein potentiates the prion-like formation of pathological inclusions. J Biol Chem 2018;293:18914–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Giasson BI, Duda JE, Quinn SM, et al. Neuronal α-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human α-synuclein. Neuron 2002;34:521–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sacino AN, Brooks M, Thomas MA, et al. Intramuscular injection of α-synuclein induces CNS α-synuclein pathology and a rapid-onset motor phenotype in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:10732–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sacino AN, Brooks M, McKinney AB, et al. Brain injection of α-synuclein induces multiple proteinopathies, gliosis, and a neuronal injury marker. J Neurosci 2014;34:12368–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yoshiyama Y, Higuchi M, Zhang B, et al. Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron 2007;53:337–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sorrentino ZA, Brooks MMT, Hudson V, et al. Intrastriatal injection of α-synuclein can lead to widespread synucleinopathy independent of neuroanatomic connectivity. Mol Neurodegener 2017;12:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National institute on aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2012;8:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 2017;89:88–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gilman S, Wenning GK, Low PA, et al. Second consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neurology 2008;71:670–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Litvan I, Hauw JJ, Bartko JJ, et al. Validity and reliability of the preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for progressive supranuclear palsy and related disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996;55:97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ichimura Y, Komatsu M.. Activation of p62/SQSTM1-Keap1-nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 pathway in cancer. Front Oncol 2018;8:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Al-Sarraj S, King A, Troakes C, et al. p62 positive, TDP-43 negative, neuronal cytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusions in the cerebellum and hippocampus define the pathology of C9orf72-linked FTLD and MND/ALS. Acta Neuropathol 2011;122:691–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mann DM, Rollinson S, Robinson A, et al. Dipeptide repeat proteins are present in the p62 positive inclusions in patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neurone disease associated with expansions in C9ORF72. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2013;1:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuusisto E, Salminen A, Alafuzoff I.. Ubiquitin-binding protein p62 is present in neuronal and glial inclusions in human tauopathies and synucleinopathies. Neuroreport 2001;12:2085–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mckee AC, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, et al. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol 2016;3:75–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hsu ET, Gangolli M, Su S, et al. Astrocytic degeneration in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol 2018;136:955–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kovacs GG, Ferrer I, Grinberg LT, et al. Aging-related tau astrogliopathy (ARTAG): Harmonized evaluation strategy. Acta Neuropathol 2016;131:87–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kuusisto E, Salminen A, Alafuzoff I.. Early accumulation of p62 in neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease: Possible role in tangle formation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2002;28:228–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Trojanowski JQ, Shin R-W, Schmidt ML, et al. Relationship between plaques, tangles, and dystrophic processes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 1995;16:335–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Masliah E, Terry RD, Mallory M, et al. Diffuse plaques do not accentuate synapse loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol 1990;137:1293–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, et al. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: Synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol 1991;30:572–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li T, Braunstein KE, Zhang J, et al. The neuritic plaque facilitates pathological conversion of tau in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Nat Commun 2016;7:12082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sacino AN, Prokop S, Walsh MA, et al. Fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome with co-occurrent progressive supranuclear palsy-like neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019;7:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vonsattel J-P, Myers RH, Stevens TJ, et al. Neuropathological classification of Huntington’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1985;44:559–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Waldvogel HJ, Kim EH, Thu DV, et al. New Perspectives on the neuropathology in Huntington’s disease in the human brain and its relation to symptom variation. J Huntingtons Dis 2012;1:143–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rüb U, Schöls L, Paulson H, et al. Clinical features, neurogenetics and neuropathology of the polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2, 3, 6 and 7. Prog Neurobiol 2013;104:38–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.