Abstract

Tangles are deposits of hyperphosphorylated tau, which are found in multiple neurodegenerative disorders that are referred to as tauopathies, of which Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common. Tauopathies are clinically characterized by dementia and share in common cortical lesions composed of aggregates of the protein tau. In this study, we explored the therapeutic potential of tolfenamic acid (TA), in modifying disease processes in a transgenic animal model that carries the human tau gene (hTau). Behavioral tests demonstrated the efficacy of TA in improving spatial learning deficits and memory impairments in young and aged hTau mice. Western blot analysis of the hTau protein revealed reductions in total tau as well as in site-specific hyperphosphorylation of tau in response to TA administration. Immunohistochemical analysis for phosphorylated tau protein revealed reduced staining in the frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum in animals treated with TA. Thus, as shown in previous published studies from our lab, TA holds the potential as a disease-modifying agent for the treatment of tauopathies including AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, tolfenamic acid, hTau mouse model, tauopathy, microtubule-associated protein Tau (MAPT)

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia. One of the pathological features of AD are the tangle deposits composed of hyperphosphorylated tau, which are found in multiple neurodegenerative disorders referred to as tauopathies [1–3]. Mutations in the tau gene are present in frontotemporal dementia (FTD, ~5% of the cases) and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) where tau aggregates are the characteristic deposits causing neurofibrillary degeneration [4–7]. Both neurofibrillary degeneration and β-amyloidosis can exist independently [8]. Neurofibrillary degeneration in the absence of β-amyloid is seen in several tauopathies such as Guam parkinsonism dementia complex, dementia pugilistica, corticobasal degeneration, Pick’s disease, FTDP-17, and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP). These aforementioned tauopathies with neocortical lesions are clinically characterized by dementia [8]. Furthermore, neurofibrillary pathology and not β-amyloidosis correlates best with the presence of dementia in humans [9].

The microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) was first isolated and identified in 1975 as a protein necessary for microtubule assembly [10]. The normal function of tau is to regulate spacing between microtubules and to stabilize them [11]. Although the exact cause of its aggregation is un-known, it has been observed that hyperphosphorylation of tau reduces its binding to microtubules and is suspected to play a role in its aggregation [2]. When tau becomes hyperphosphorylated, it loses the ability to bind to microtubules, and eventually leads to the formation of insoluble neurofibrillary aggregates [12]. Moreover, hyperphosphorylated tau suppresses microtubule assembly suggesting that phosphorylation regulates the functions of tau [8, 13, 14].

At present, there are no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs that are known to modify tangles. Tolfenamic Acid (TA), commercially known as Clotam®, is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) currently used in Europe and other countries to treat symptoms of migraine headaches and is available in 200 mg tablet form [15]. TA has been used as a migraine medicine for decades in Europe; however, TA is not approved for any indication in the United States. Recently, we obtained designation by the European Medicine Agency and the US FDA to conduct human studies using TA as a potential treatment for FTD and PSP.

The present study was conducted to determine the ability of TA to modulate the overexpression of tau-related biomarkers and the severity of cognitive deficits and tauopathy in an animal model containing the promoter and coding sequences for the human tau gene (hTau). We evaluated the effect of TA on cognitive function, protein expression of total tau as well as site-specific tau phosphorylation and immunohistological localization. Our results indicate that TA has the ability to impact each of these measures, and we believe that TA offers great promise as a therapeutic intervention for AD and other tauopathies.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animal Model

The hTau transgenic mouse model used in this study, strain B6.Cg-Mapttm1(EGFP)Klt Tg(MAPT)8cPdav/J, was obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The animals are hemizygous for the hTau gene, expressing all six isoforms of human tau (3R and 4R). The transgene contains the coding sequence, intronic regions, and regulatory elements of the endogenous human promoter region. These mice are also homozygous knockouts of murine tau. Hyperphosphorylated tau is detected in these mice by 3-months of age. Visuospatial and learning deficits occur as early as 6 months of age as assessed by the Morris Water Maze (MWM) [16].

In order to establish the transgenic mouse colony, mice were bred and genotyped in-house at the University of Rhode Island (URI). The room temperature was maintained at 22 ±2°C with humidity levels of 55 ±5%, and with a 12:12 hour light-dark cycle (light on at 6:00 AM; light off at 6:00 pm). Food and water were available for mice ad-libitum. To ensure the validity of genotyping results, genotyping was performed by two separate methods via standard PCR followed by gel electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel [17]. The University of Rhode Island Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (URI IACUC) approved all protocols including the breeding, genotyping and experimental methods, and animals were under continuous supervision by a URI veterinarian for the duration of the study and during drug administration.

2.2. Assessment of Cognitive Deficit in the hTau Transgenic Mouse Model

To assess spatial learning and memory, animals were tested in the MWM. In this task, the mice had to locate the hidden platform by learning multiple spatial relationships between the platform and the distal extra-maze cues [18–20]. The maze apparatus consisted of a white pool (48” diameter, 30” height) filled with water to a depth of 14”. White, non-toxic paint (Crayola, New York City, NY, USA) was used to make the water opaque. The pool was virtually divided into four quadrants namely North West (NW), North East (NE), South West (SW), and South East (SE). Distinct visual cues were placed along the sides of the pool to guide the animals to the escape platform. A clear Plexiglas escape platform (10 cm2) was submerged in the NW quadrant, 0.5 cm below the surface of the water. Water temperature was maintained at 25 ±2°C during all procedures. On Day 15 of drug administration, we began behavioral tests and continued drug administration until the last day of the behavioral test. We began with a habituation trial that allowed the mice to swim freely for 60 sec to acclimate to the experiment. Mice received 3 daily training sessions for a total of 8 days with a 20 min inter-trial interval. The starting position was randomly assigned between three possible positions, while the platform position remained fixed for all the trials. Each animal was allowed to swim until they found the immersed, hidden platform or for a maximum duration of 60 sec. If a mouse failed to locate the platform, it was gently guided to the platform and made to rest on it for 30 sec. Mice were also left to sit on the platform for a maximum duration of 10 sec upon successful trial. Following the completion of 8 training day sessions, probe trials for up to 60 sec were performed on Days 24 and 34 of the study to assess long-term memory retention (Fig. 1A). Memory of the platform location would be an indication that the mice had developed a preference for the correct quadrant (the quadrant that contained the hidden platform during the previous training sessions). The swim paths and latencies were videotaped and analyzed with a computerized video-tracking system (Object-Scan, Clever Sys. Inc., Reston, VA, USA).

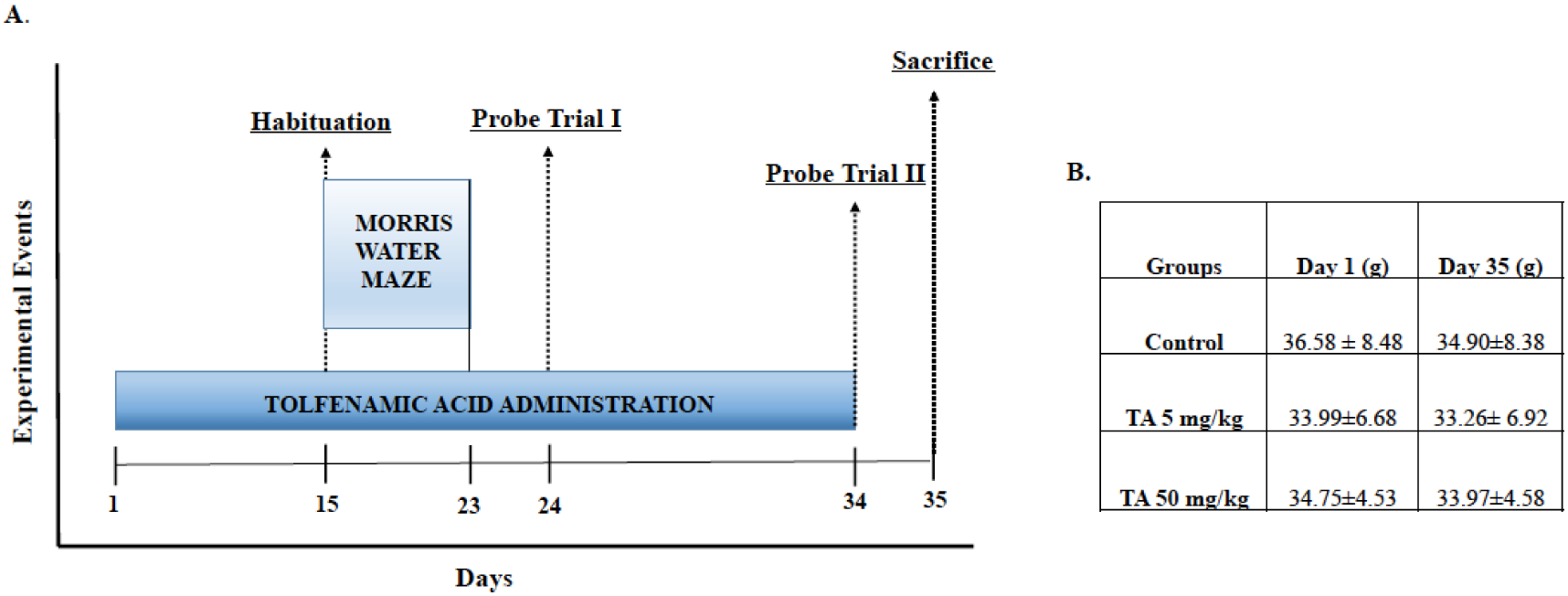

Fig. (1). A timeline of TA administration and behavioral assessment and body weight measurements.

(A) Mice were administered TA daily for 34 days. Behavioral testing in the Morris water maze began on the 15th day of dosing with daily training sessions that lasted until the 23rd day of the study. On the 24th day of dosing, we conducted the first session of probe trials and then we performed a second session of probe trials on the 34th day of dosing to assess for long-term memory retention. Animals were euthanized on the 35th day of the study and brain tissue was dissected, collected and stored in the −80°C freezer. (B) Average mice weight of each group with administration of either vehicle only or TA.

2.3. Animal Dosing and Tissue Collection

Our previous work has shown that the effectiveness of TA was similar in both female and male mice and thus to conserve the numbers of animals used, we have utilized different genders for various endpoints. Since the transgenic mice used in the present study are known to start accumulating tangles at 3 months of age, we used male transgenic mice aged between 3–4 months and older mice with advanced pathology (16–18 months) to examine the ability of TA to improve the memory and learning deficits of the mice.

Mice were divided into three groups with ten mice in each group. Administration of either TA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or corn oil vehicle via oral gavage was carried out for 34 days (Fig. 1A); Group 1: hTau; Control carrier administered with corn oil vehicle (C, Tau +/+), Group 2: hTau; Carrier mice administered with TA (5 mg/kg) dissolved in corn oil (TA 5mg, Tau +/+), and Group 3: hTau; Carrier mice administered with TA (50 mg/kg) dissolved in corn oil (TA 50 mg, Tau +/+). Since the optimal dose was determined from the younger mice and prior published work [21, 22], older mice aged 16–18 months were only dosed with 5 mg/kg TA. After the completion of the behavioral test on Day 35, the mice were euthanized in a CO2 chamber and brain tissues were extracted, dissected, and stored at −80°C until further use.

2.4. Immunohistochemical Analysis

Although tau pathology was expected to begin at 3 months of age, we wanted to ensure the presence of well-developed histochemical conditions at an older age. Female mice aged 13 months were used for the immunohistochemistry investigation in order to determine the ability of TA to alleviate tau pathology. The mice were divided into three respective groups as follows: Group 1: Control Carrier administered with corn oil vehicle (C, Tau +/+, n = 3), Group 2: Carrier mice administered TA in corn oil at a dose of TA 5 mg/kg (n = 3), or Group 3: Carrier mice administered with TA in corn oil at a dose of TA 50 mg/kg (n = 4).

The mice were euthanized after 34 days of TA treatment for immunohistochemical studies. They were deeply anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 0.1 ml/10 g of xylazine-ketamine mixture (100 mg/ml-10 mg/ml) and perfused transcardially with 100 ml of perfusion wash consisting of 0.8% sodium chloride, 0.8% sucrose, 0.4% dextrose, 0.034% anhydrous sodium cacodylate, and 0.023% calcium chloride. Mice were then perfused with 100 ml of perfusion fix that consisted of 4% paraformaldehyde, 4% sucrose, and 1.07% anhydrous sodium cacodylate (pH 7.2–7.4) and their brains were removed. The extracted brains were post-fixed in the perfusion fix solution overnight and then they were cryopreserved in 30% sucrose solution. Fixed brains were sent “blind” to NeuroScience Associates (Knoxville, TN, USA), where they were sectioned in the coronal plane and stained for p-tau Thr231 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, MA, USA) at a dilution of 1:2500.

2.5. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Brain tissues were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated on ice for 1 hr. The homogenates were centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and supernatants were collected and used for western blot analysis. Protein concentration was determined by Pierce bicinchoninic assay (BCA) kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The efficacy of the drug was evaluated by analyzing the protein levels in the frontal cortex and cerebellum. Although the cerebellum does not exhibit AD pathology, it is packed with cells and thus would give a much better signal to noise ratio to validate these findings using Western blot analysis. Furthermore, it will show that the drug can act on its target in the same manner everywhere in the brain.

For total tau, site-specific phosphorylation 40 μg of total protein was separated onto a 10–12% polyacrylamide gel at 100 V for 2 hours and then transferred to a polyvinylidiene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE-Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris buffer saline +0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) at room temperature for 1 hr. Immunoblotting was performed after overnight exposure to the following antibodies diluted at 1:1000 with gentle agitation on a shaker at 4°C: total tau (ab32057, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); Tau-46 (4019, Cell Signaling Technology, Denver, MA, USA); Thr181(12885, Cell signaling Technologies, MA, USA); Thr231 (710126, Thermo Scientific). On the following day, membranes were washed and exposed to IRDye 680l T Infrared Dye (LI-COR Biotechnology, NE, USA), goat anti-mouse/goat anti-rabbit diluted at 1:10,000 for 1 hr. The images were developed using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR). As a control for equal protein loading, membranes were stripped and re-probed with rabbit glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) antibody, diluted at 1:2500, and exposed to anti-rabbit IRDye 800LT Infrared Dye (LI-COR) diluted at 1:10,000 for 1 hr. The intensities of the Western blot bands were obtained using Odyssey V1.2 Software (LI-COR). After transferring to a PVDF membrane, the gel was stained with Bio-safe Coomassie blue stain (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) to assess the loading of the samples.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were represented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Assessment of performance in MWM daily training sessions was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison post-test, using GraphPad InStat 3 software (Graph Pad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical analysis of Western blot bands was determined by one-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak comparisons with Sigma Stat 3.5 software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Results with a p-value of < 0.05 or < 0.01 were considered statistically significant and were marked with asterisks accordingly.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Overt Toxicity

Mice were dosed with TA for 34 consecutive days (Fig. 1A). Mice were weighed on Day 1 and Day 35 of TA administration, and no changes in body weight were observed (Fig. 1B). Additionally, no overt gross morphological changes were seen in tissue sections of these animals. Treatment with TA did not result in any abnormal behavior compared to non-exposed mice. Furthermore, TA treatment did not affect swim speed and velocity of these animals (Fig. 2B and 3B).

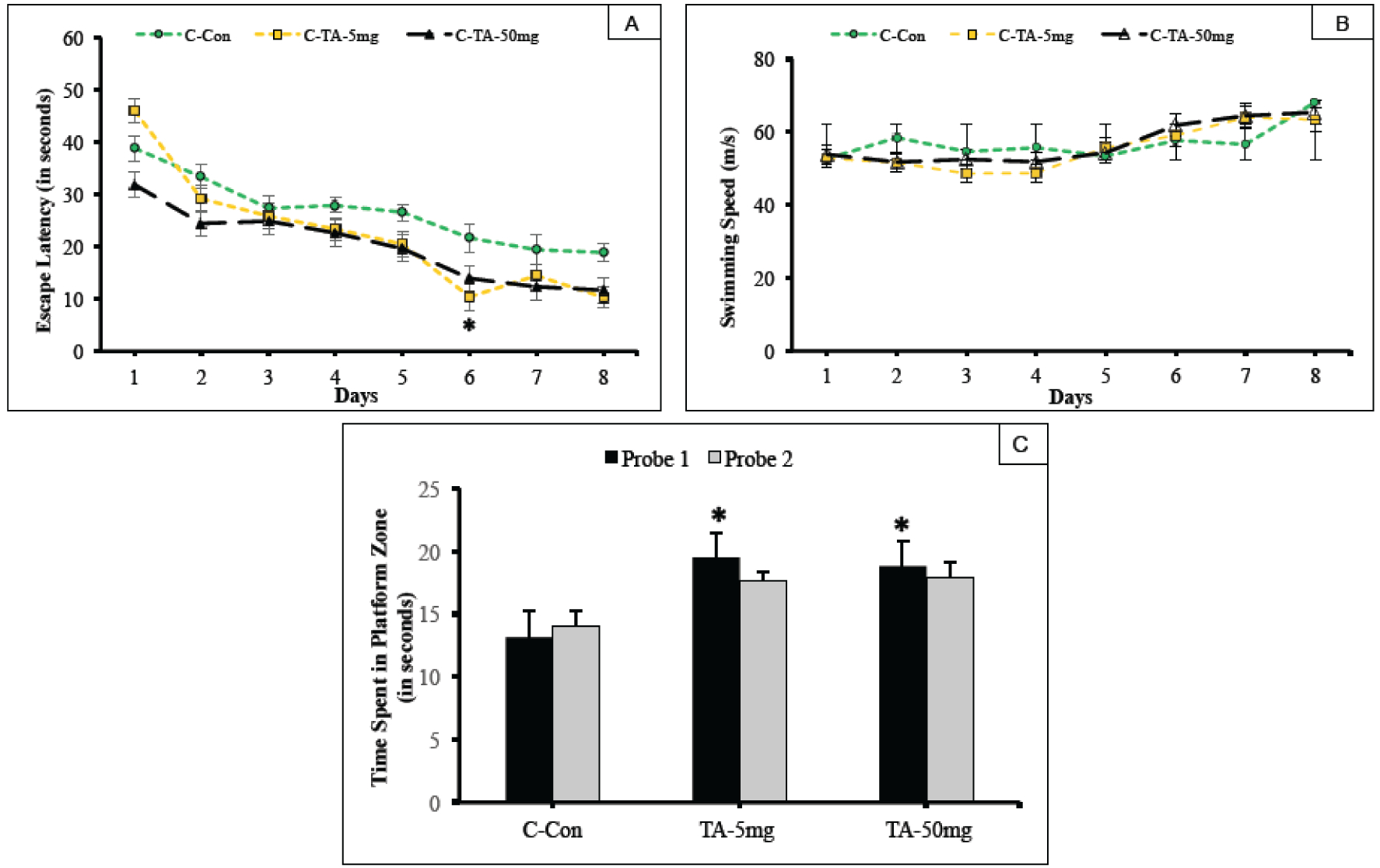

Fig. (2). Effect of TA on acquisition and memory retention in 3–4 month old hTau knock-in mice.

Training in the Morris water maze consisted of three trials per day for 8 days to locate a hidden platform. (A) Mean escape latencies for finding the platform during daily training sessions. (B) Average swimming speed of mice along the 8-day session. (C) Memory retention was assessed by a 60 sec probe trial conducted 24 hours (Probe trial 1) after the last day of acquisition testing, and again repeated for memory retention after 10 days (Probe trial 2). The trials measured the time spent in the platform zone of the correct quadrant. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p <0.05 as compared with carrier control (C, Tau +/+).

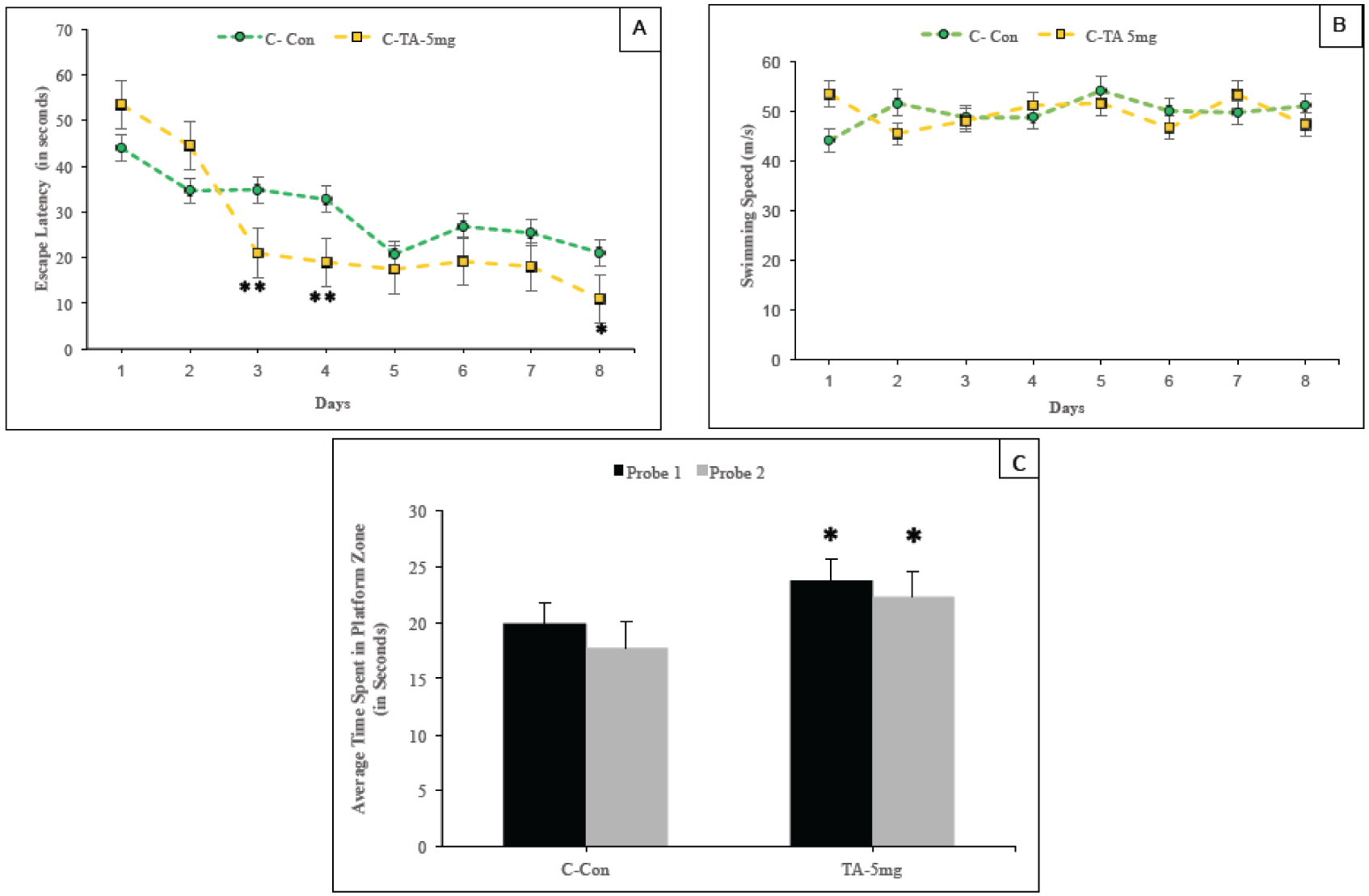

Fig. (3). Impact of TA on acquisition and memory retention in 16–18-month old hTau knock-in mice.

Training in the Morris water maze consisted of three trials per day for 8 days to locate a hidden platform. (A) Mean escape latencies for finding the platform during daily training sessions. (B) Average swimming speed of Control carrier (C, Tau+/+) and carrier mice administered with TA (TA 5mg, Tau+/+) along the 8-day session. (C) Memory retention was assessed by a 60-second probe trial 24 hours (Probe trial 1) after the last day of acquisition testing and again repeated for memory retention after 10 days (Probe trial 2). The trials measure the time spent in the platform zone of the correct quadrant. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean**.

3.2. Attenuation of Cognitive Impairment by the Administration of TA in Young and Aged hTau Mice

The present study evaluated memory in animals (aged 3–4 months) that received 5 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg TA or vehicle control. In the daily sessions which consisted of three trials per day for a total duration of eight days, the performance of animals in the 5 and 50 mg/kg TA treatment groups exhibited an improved trend over the training course of 8 days, as compared to the untreated control carrier group assessed by escape latencies. However, there were no significant differences between the C, TA 5mg and TA 50mg observed on all but one daily session (Day 6), which revealed significance (p<0.05) for mice administered with TA 5 mg/kg over C (Fig. 2A).

Probe trials assessed the time spent by the mice in the correct platform zone. On Day 24, Probe trial 1 followed one day after the completion of 8 consecutive training days. The trial showed a significant amount of time was spent in the correct platform zone by the hTau carrier mouse treated with 5 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg TA compared to C (p<0.05) (Fig. 2C). After a long delay of 10 days, a second probe trial was conducted on Day 34 of the study to assess the memory retention of the mice. hTau carrier mice receiving TA (5 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg) retained their cognitive function and their long-term memory of the platform’s location and performed better when compared to C; however, significance was not observed when compared to the Control group (Fig. 2C). These improvements can be attributed to enhanced cognitive function, since data depicted in Fig. 2B shows no impact of the treatment on swimming speed.

The ability of TA to improve learning and memory processes was also evaluated in aged hTau carrier mice. In the case of older mice (16–18 months), treatment with TA had an earlier impact during the training sessions as compared to the younger siblings. Analysis of the test session score revealed significant decrease in the latency on day 3, day 4 (p<0.01) and day 8 (p<0.05) in aged mice that received TA (TA 5mg) as compared to aged matched control group (Fig. 3A). Spatial memory retention was also assessed in the older mice using Probe trial 1 and 2. Again the mice carrying the hTau gene and receiving TA showed a significant improvement over similar untreated mice. Briefly a greater impact on memory performance was observed in aged hTau mice treated with TA. No impact on swimming velocity was seen in accordance with tau nor TA (Fig. 3B).

3.3. Effect of TA on the Levels of Total Tau and Phospho-tau (p-tau)

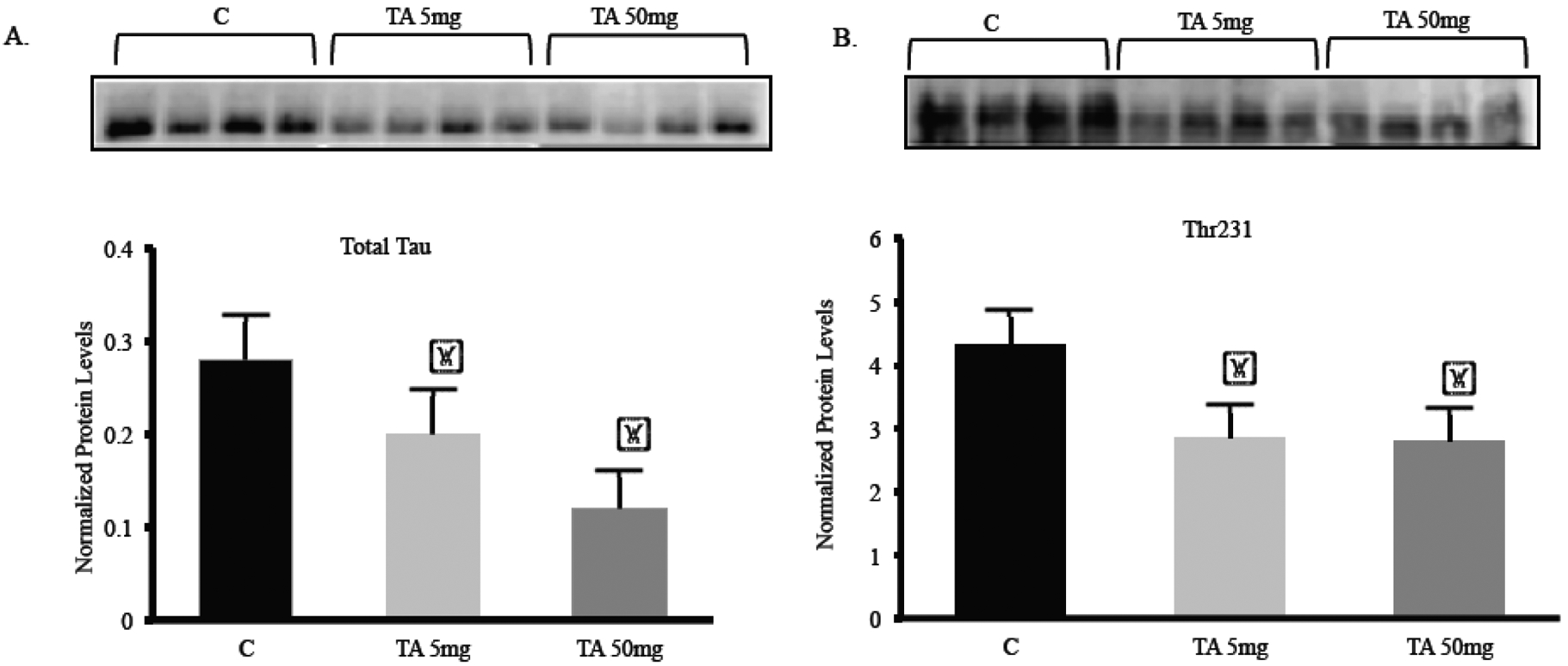

The protein levels of cortical total tau and site-specific hyperphosphorylated tau relative to GAPDH were profiled by Western blotting in hTau mice aged 3–4 months, following the treatments with vehicle, TA 5 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg for a duration of 34 days. These were the cohort of the young animals tested behaviorally above. One-way ANOVA analysis demonstrated that a significant difference in the total tau protein levels was present. Total tau levels were significantly (p<0.05) decreased in both the TA 5 mg and TA 50 mg treated groups compared to control group, (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the higher improvement of behavioral performance in aged mice, we also found a concomitant reduction in tau levels (Fig. 4A).

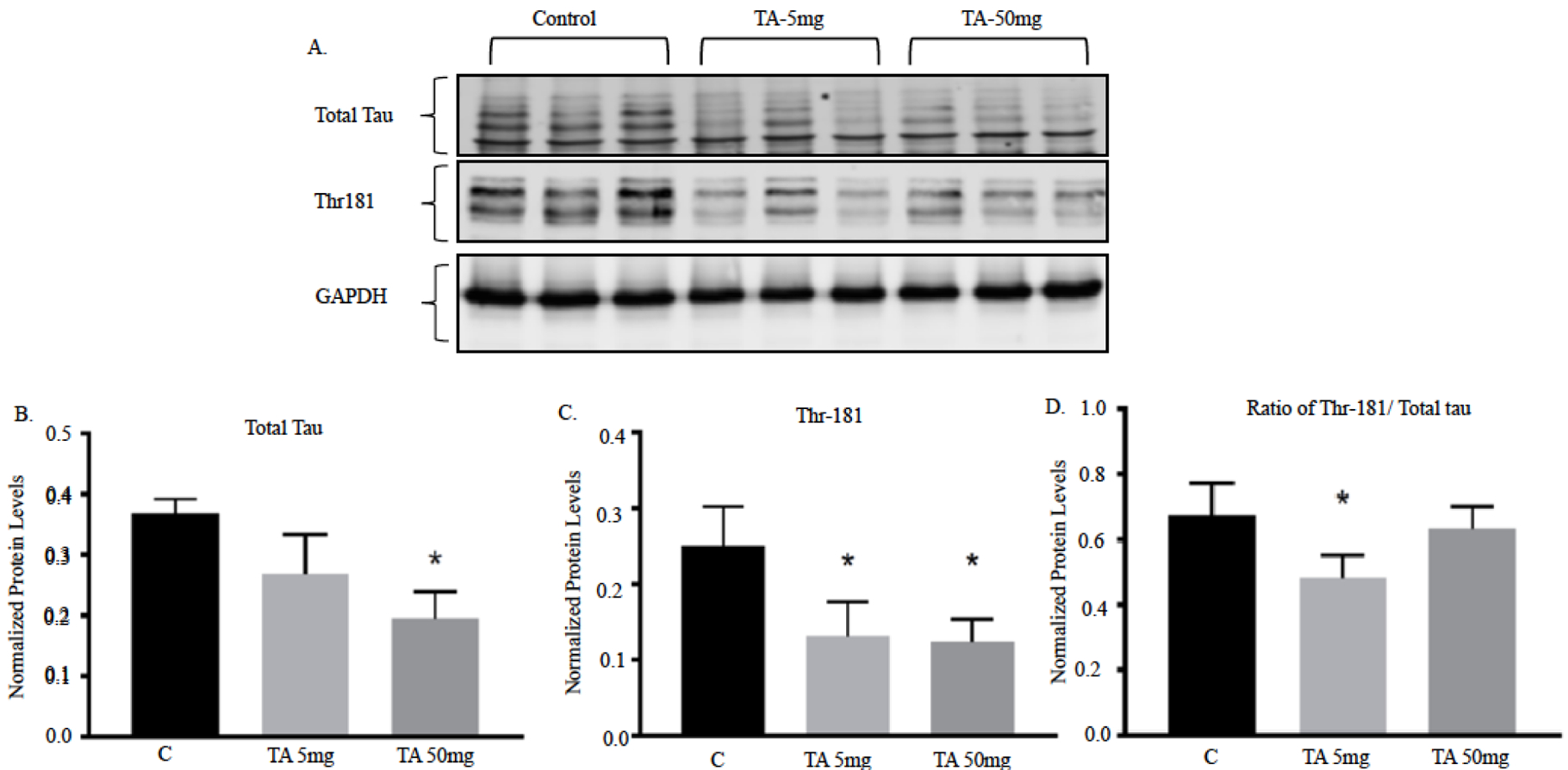

Fig. (4). Brain cortical total tau and site specific phosphorylation of tau after TA administration in hTau knock-in mice.

Mice aged 3–4 months were treated with vehicle control (C; corn oil), 5, or 50 mg/kg TA for 34 consecutive days. (A–B) Quantification of total tau and phospho-tau (Thr231) in the frontal cortex of young mice normalized against GAPDH. Each data point in the histogram is the mean ± SEM, n = 4. “*” indicates significantly lower than the control determined by one-way ANOVA (p = 0.032) and p < 0.05 according to Holm-Sidak post-test.

Hyperphosphorylation of tau results in loss of its ability to bind and stabilize microtubules, thus effect of TA treatment on the site-specific hyperphosphorylation was also scrutinized. p-tau Thr231 protein was quantified relative to GAPDH levels and the ratio of Thr231/GAPDH depicted a significant (p<0.05) reduction in the levels of Thr231 in both TA 5mg and TA 50 mg groups compared to control (Fig. 4B).

The effects of lowering total tau and hyperphosphorylation at site Thr181 were also analyzed with TA administration. Total tau and p-tau Thr181 protein levels were measured by Western blot and normalized to GAPDH levels in mice cerebellum tissue, aged 3–4 months (Fig. 5A). Quantification of the Western blot showed a decrease in total tau levels for mice dosed with TA (Fig. 5B). A significant decrease in total tau protein was seen in the TA 50 mg group when compared to control. p-tau Thr181 was significantly decreased in both TA 5 mg and TA 50 mg (Fig. 5C). Lastly, the ratio of Thr181/ total tau was measured (Fig. 5D). There was a decrease in the ratio of Thr181/ total tau for both the TA 5 mg and TA 50 mg groups when contrasted with the control mice. A significant lowering of Thr181/ total tau was seen in the TA 5 mg compared to the control group.

Fig. (5). Total protein and site specific phosphorylation of tau in the cerebellum of hTau knock-in mice after dosing with TA.

Young mice aged 3–4 months were administered with vehicle (corn oil), 5, or 50 mg/kg TA for 34 consecutive days. (A–B) Quantification of total tau and phospho-tau (Thr181) in the cerebellum of young mice normalized against GAPDH. Each data point in the histogram is the mean ± SEM, n = 3. “*” at what p value indicates reduction compared to control determined by students t-test.

3.4. Reduction of Hyperphosphorylation (p-tau Thr231) Staining Intensity in Various Brain Regions

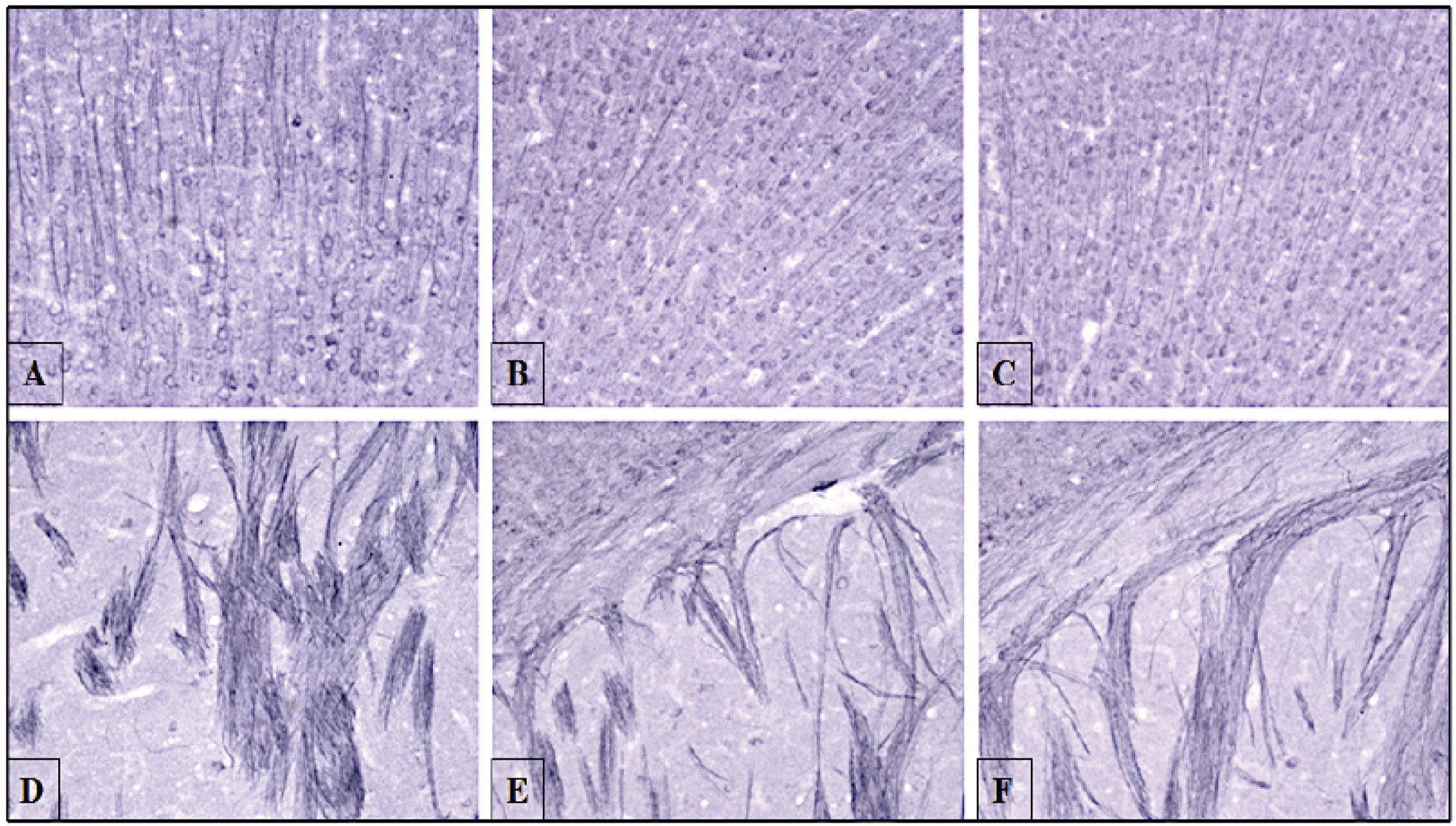

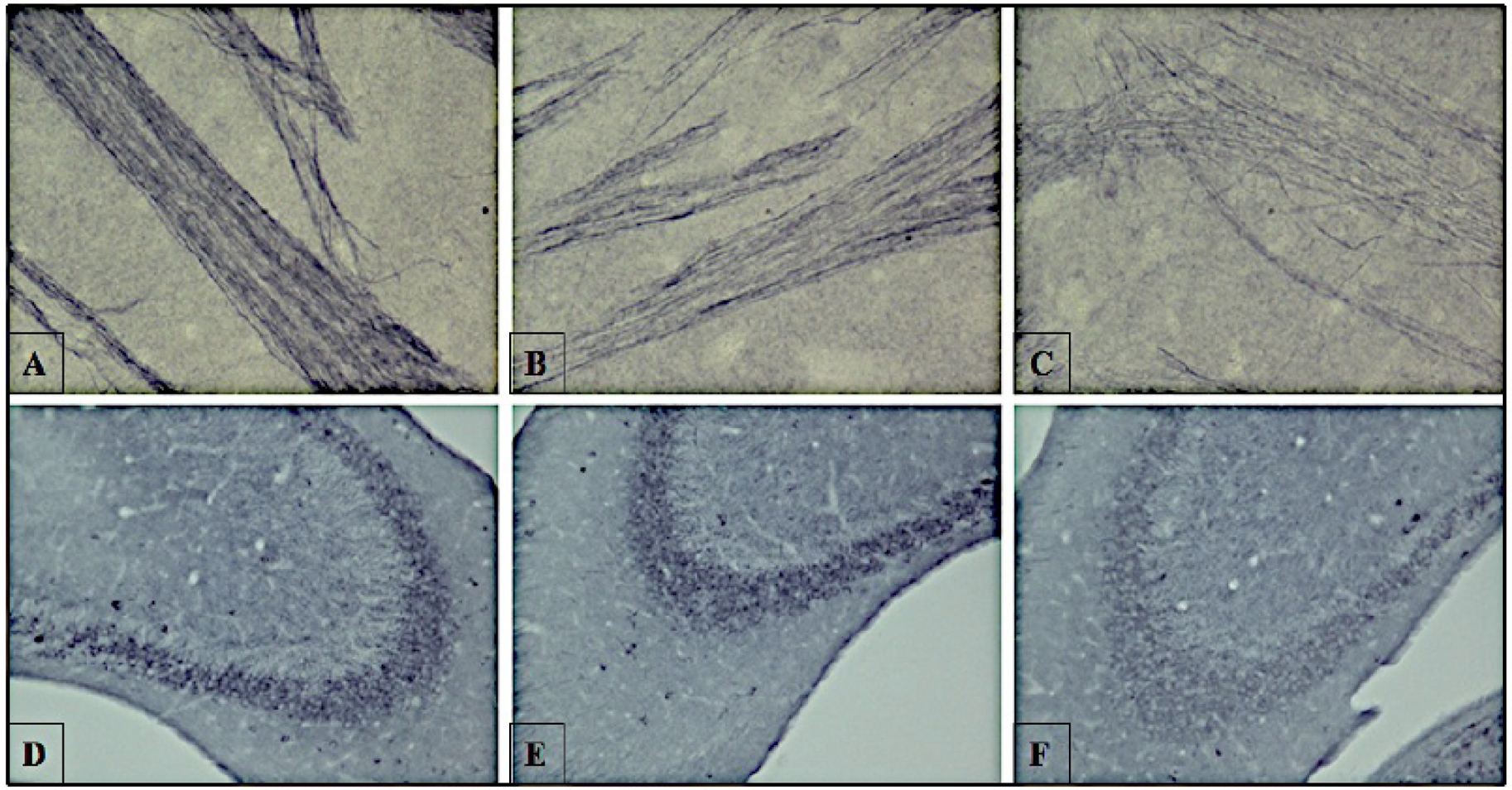

We also studied the distribution of hyperphosphorylated tau in the cortex, hippocampus, and striatum of 13-month-old, female hTau mice treated with vehicle, 5, or 50 mg/kg TA. Increased immunostaining of Thr231 in cell bodies, dendrites and proximal axons was observed in the carriers control group. A reduction in the immunostaining was observed in hT au mice, which were dosed with either 5 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg TA (Fig. 6), with the higher dose exhibiting greater reductions. Higher magnification images from the striatum and hippocampus show the fibrillary and intracellular nature of the tau images (Fig. 7).

Fig. (6). Immunohistochemistry staining of frontal cortex and striatum with Thr231 antibody in hTau mice aged 13 months.

Mice aged 13 months were dosed with vehicle (corn oil), 5 or 50 mg/kg TA for 34 days. Following perfusion, frontal cortex and striatum regions were stained with antibody against tau Thr231 phosphorylation. Cell bodies and dendrites in the frontal cortices were imaged for (A) vehicle (corn oil) (B) TA 5 mg/kg (C) TA 50 mg/kg. Images are shown at 20X magnification. The internal capsule of axonal tracts located in the striatum were imaged for (D) vehicle (corn oil) (E) TA 5 mg/kg (F) TA 50 mg/kg. Images are shown at 20x magnification.

Fig. (7). Striatal and hippocampal immunohistochemistry staining of phosphorylation site Thr231 in hTau mice aged 13 months.

Mice aged 13 months were dosed with vehicle only, 5, or 50 mg/kg TA for 34 days. Following perfusion, the internal capsule of axons in the striatum (A–C) and hippocampus regions (D–F) were stained with antibody against tau Thr231 phosphorylation. The internal capsule of axons in the striatum were imaged for (A) vehicle (corn oil) (B) TA 5 mg/kg (C) TA 50 mg/kg. Phosphorylated tau in the hippocampi were shown with TA dosing at (D) vehicle (corn oil) (E) TA 5 mg/kg (F) TA 50 mg/kg. Images are shown at 40x magnification.

4. DISCUSSION

Our published research has demonstrated that TA reduces AD-related biomarkers such as: amyloid precursor protein (APP) and β-secretase (BACE1) [21, 22]. TA also improves spatial learning in human APP knock-in mice [23, 24]. While we attributed these improvements in behavioral measures to the reduction in amyloid-β (Aβ) plaque burden, we further considered the potential impact of TA on tau-related biomarkers as well. Indeed, we found that the transgenic APP mice that received TA exhibited lower levels of murine total tau, p-tau Ser235, p-tau Thr181 and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) [25]. These data gave us reason to believe that TA has the potential to impact the overexpression of both Aβ and tau and prompted us to determine the contribution of each pathway to cognitive dysfunction.

Consistent with our earlier reports with APP transgenic mice [23, 24], short-term administration of TA was able to reverse the cognitive impairment present in hTau mice. It is important to recognize that TA affected cognitive measures and the expression of tau-related biomarkers at the lowest dose tested and following a very limited period of administration. As previously noted by Subaiea and colleagues [23, 24], most laboratory studies of potential AD therapies rely on treatment periods of 2 months or longer to demonstrate an effect on cognitive function. We were able to demonstrate significant improvement in cognitive measures following a treatment period of only 34 days. This impact on cognitive function was also selective as the drug treatment did not affect swim latencies or velocity, ruling out that the improved performance was not due to overall well-being or nonspecific actions of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID).

Recent reports have found that hyperphosphorylated tau and not Aβ is correlated with memory impairment [26]. Seminal studies by Oddo and coworkers, using transgenic mice models that express plaques and tangles, demonstrated that reducing the levels of soluble tau and Aβ improved cognitive function, while lowering soluble Aβ alone did not improve cognition [27]. In addition, accumulation of neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) is a later manifestation of tau pathology, and hyperphosphorylation of tau is mainly responsible for neurodegenerative damage [8, 26, 28].

Total tau and p-tau protein levels were reduced in both the low and high dose treatment group compared to the control group. This was observed when phosphorylation was measured in relation to a housekeeping gene or expressed as a ratio of total tau. It also occurred in both genders of young and aged mice and was corroborated independently by the reduced immunohistochemical intensity of p-tau in middle-aged mice (13 months), conducted by a contractor blind to the identity of the samples. In addition to the overt change in tau staining in mice dosed with TA, one could also see that TA also reduced the fibrillary nature of the staining, suggesting that this drug can interfere with tangle formation and tau deposition.

CONCLUSION

This study provides evidence that treatment of transgenic mice carrying the human tau gene with TA can have an impact on cognitive performance of the mice through reduction in the levels of tau, phospho-tau and are accompanied by a lowering of pathological features of tau deposition and hyperphosphorylation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and by the NIH grants ES13022, AG027246, 1R56ES01568670-01A1, and 1R01ES015867-01A2 awarded to NHZ. The research was made possible by the use of the RI-INBRE Research Core Facility, supported by the NIGMS/NIH Grant # P20GM103430.

Footnotes

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Publisher's Disclaimer: DISCLAIMER: The above article has been published in Epub (ahead of print) on the basis of the materials provided by the author. The Editorial Department reserves the right to make minor modifications for further improvement of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci 24: 1121–59 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Brunden KR, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Advances in tau-focused drug discovery for Alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 8(10): 783–93 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Santpere G, Nieto M, Puig B, Ferrer I. Abnormal Sp1 transcription factor expression in Alzheimer disease and tauopathies. Neurosci Lett 397(1–2): 30–4 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, et al. Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393(6686): 702–5 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hong M, Zhukareva V, Vogelsberg-Ragaglia V, Wszolek Z, Reed L, Miller BI, et al. Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct tau isoforms of hereditary FTDP-17. Science 282(5395): 1914–7 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gao L, Tucker KL, Andreadis A. Transcriptional regulation of the mouse microtubule-associated protein tau. Biochim Biophys Acta 1681(2–3): 175–81 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Goedert M, Spillantini MG. Pathogenesis of the tauopathies. J Mol Neurosci 45(3): 425–31 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX, Grundke-Iqbal I. Tau in Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res 7(8): 656–64 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 42(3 Pt 1): 631–9 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weingarten MD, Lockwood AH, Hwo SY, Kirschner MW. A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 72(5): 1858–62 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Al-Bassam J, Ozer RS, Safer D, Halpain S, Milligan RA. MAP2 and tau bind longitudinally along the outer ridges of microtubule protofilaments. J Cell Biol 157(7): 1187–96 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Beyreuther K, Masters CL. Alzheimer’s disease. Tangle disentanglement. Nature 383(6600): 476–7 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Drechsel DN, Hyman AA, Cobb MH, Kirschner MW. Modulation of the dynamic instability of tubulin assembly by the microtubule-associated protein tau. Mol Biol Cell 3(10): 1141–54 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cohen TJ, Guo JL, Hurtado DE, Kwong LK, Mills IP, Trojanowski JQ, et al. The acetylation of tau inhibits its function and promotes pathological tau aggregation. Nat Commun 2: 252 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Krymchantowski AV. The use of combination therapies in the acute management of migraine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2(3): 293–7 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Phillips M, Boman E, Osterman H, Willhite D, Laska M. Olfactory and visuospatial learning and memory performance in two strains of Alzheimer’s disease model mice-a longitudinal study. PLoS One 6(5): e19567 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dash M, Eid A, Subaiea G, Chang J, Deeb R, Masoud A, et al. Developmental exposure to lead (Pb) alters the expression of the human tau gene and its products in a transgenic animal model. Neurotoxicology 55: 154–9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gulinello M, Gertner M, Mendoza G, Schoenfeld BP, Oddo S, LaFerla F, et al. Validation of a 2-day water maze protocol in mice. Behav Brain Res 196(2): 220–7 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Laczo J, Vlcek K, Vyhnalek M, Vajnerova O, Ort M, Holmerova I, et al. Spatial navigation testing discriminates two types of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Behav Brain Res 202(2): 252–9 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Prot 1(2): 848–58 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Adwan L, Subaiea GM, Basha R, Zawia NH. Tolfenamic acid reduces tau and CDK5 levels: implications for dementia and tauopathies. J Neurochem 133(2): 266–72 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Adwan LI, Basha R, Abdelrahim M, Subaiea GM, Zawia NH. Tolfenamic acid interrupts the de novo synthesis of the beta-amyloid precursor protein and lowers amyloid beta via a transcriptional pathway. Curr Alzheimer Res 8(4): 385–92 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Subaiea GM, Adwan LI, Ahmed AH, Stevens KE, Zawia NH. Short-term treatment with tolfenamic acid improves cognitive functions in Alzheimer’s disease mice. Neurobiol Aging 34(10): 2421–30 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Subaiea GM, Ahmed AH, Adwan LI, Zawia NH. Reduction of amyloid-beta deposition and attenuation of memory deficits by tolfenamic acid. J Alzheimers Dis 43(2): 425–33 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Adwan L, Subaiea GM, Zawia NH. Tolfenamic acid downregulates BACE1 and protects against lead-induced upregulation of Alzheimer’s disease related biomarkers. Neuropharmacology 79: 596–602 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Medina M Recent developments in tau-based therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov 6(1): 20–30 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Oddo S, Vasilevko V, Caccamo A, Kitazawa M, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM. Reduction of soluble Abeta and tau, but not soluble Abeta alone, ameliorates cognitive decline in transgenic mice with plaques and tangles. J Biol Chem 281(51): 39413–23 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med. 8(6): 595–608 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]