Abstract

Background

Anaemia is a frequent condition during pregnancy, particularly among women in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Traditionally, gestational anaemia has been prevented with daily iron supplements throughout pregnancy, but adherence to this regimen due to side effects, interrupted supply of the supplements, and concerns about safety among women with an adequate iron intake, have limited the use of this intervention. Intermittent (i.e. two or three times a week on non‐consecutive days) supplementation has been proposed as an alternative to daily supplementation.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of intermittent supplementation with iron alone or in combination with folic acid or other vitamins and minerals to pregnant women on neonatal and pregnancy outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (31 July 2015), the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (31 July 2015) and contacted relevant organisations for the identification of ongoing and unpublished studies (31 July 2015).

Selection criteria

Randomised or quasi‐randomised trials.

Data collection and analysis

We assessed the methodological quality of trials using standard Cochrane criteria. Two review authors independently assessed trial eligibility, extracted data and conducted checks for accuracy.

Main results

This review includes 27 trials from 15 countries, but only 21 trials (with 5490 women) contributed data to the review. All studies compared daily versus intermittent iron supplementation. The methodological quality of included studies was mixed and most had high levels of attrition.The overall assessment of the quality of the evidence for primary infant outcomes was low and for maternal outcomes very low.

Of the 21 trials contributing data, three studies provided intermittent iron alone, 14 intermittent iron + folic acid and four intermittent iron plus multiple vitamins and minerals in comparison with the same composition of supplements provided in a daily regimen.

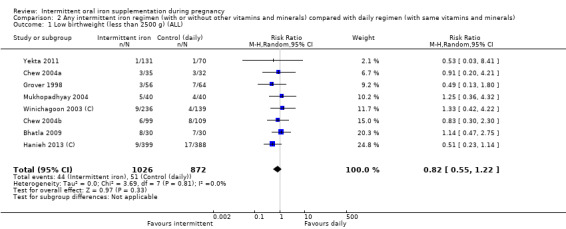

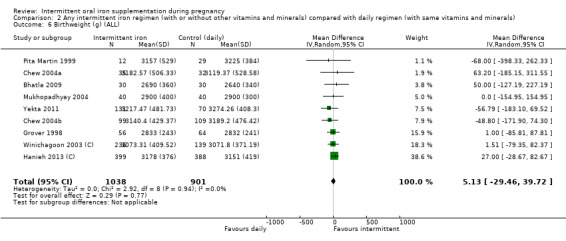

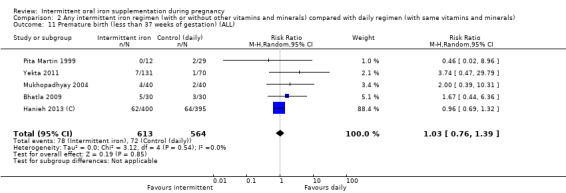

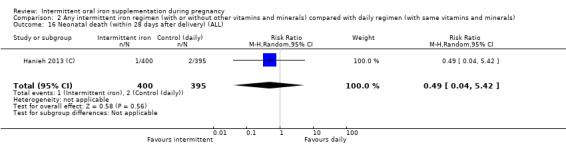

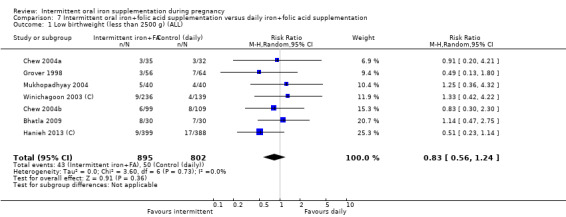

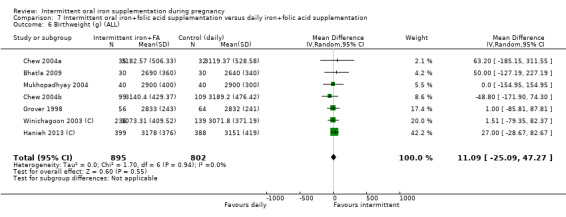

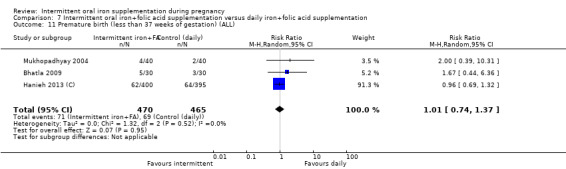

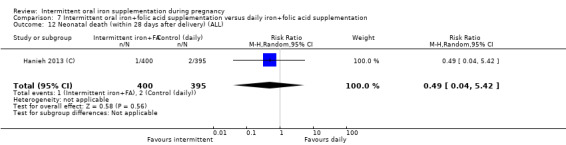

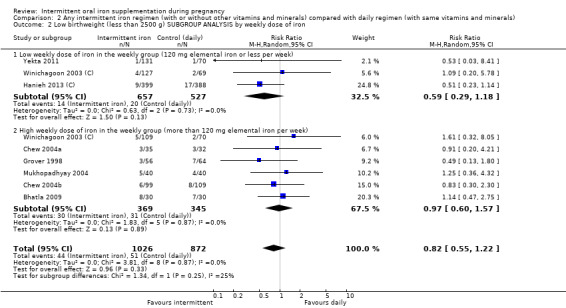

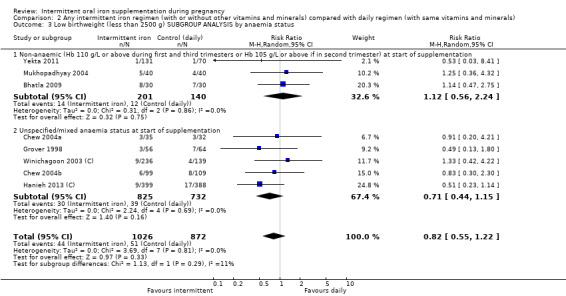

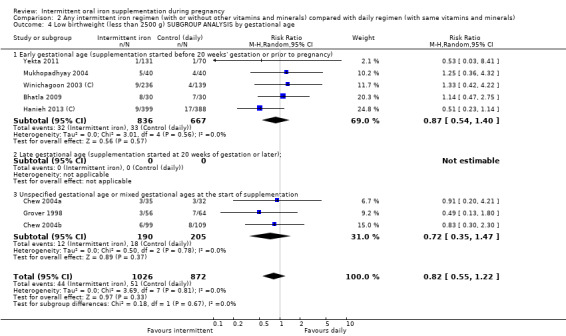

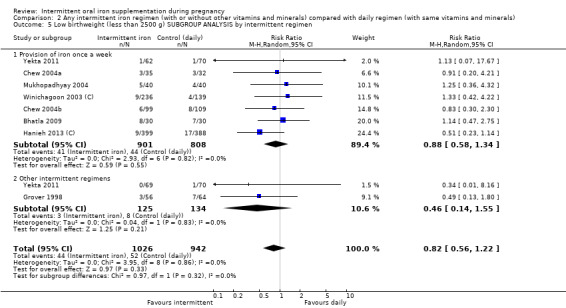

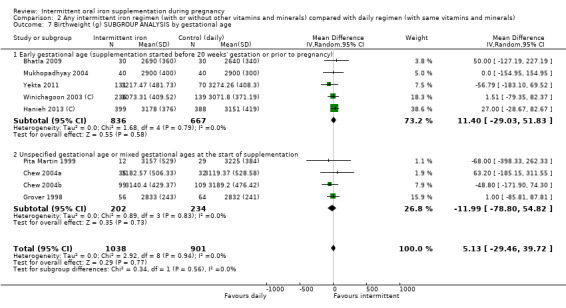

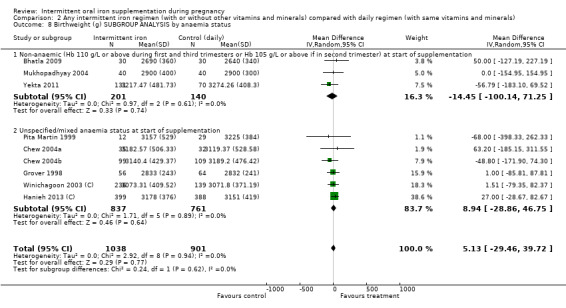

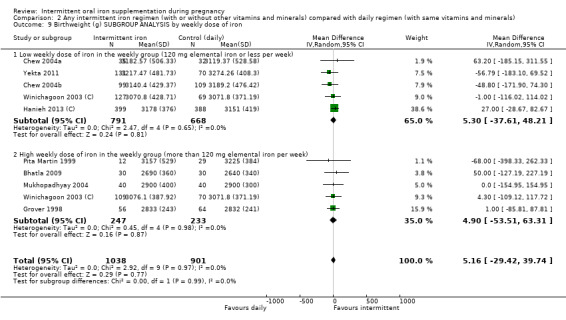

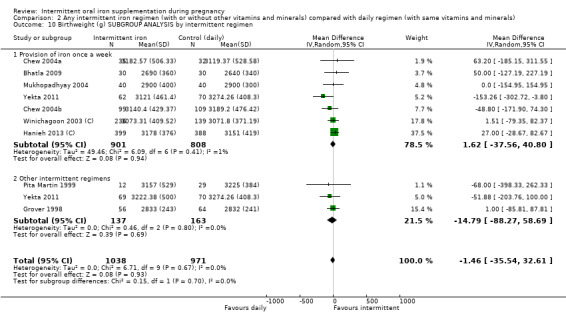

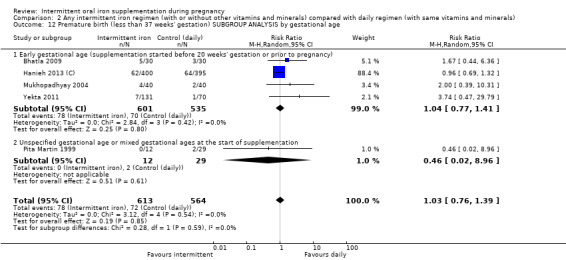

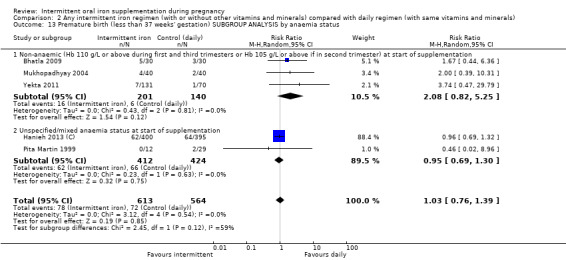

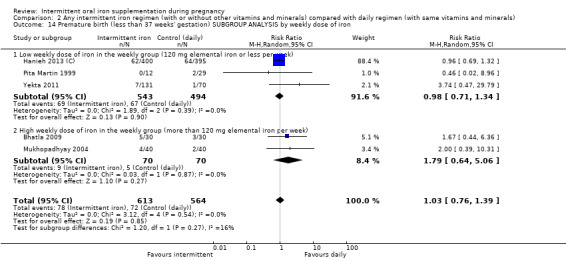

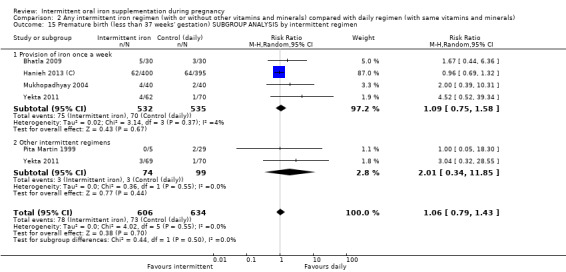

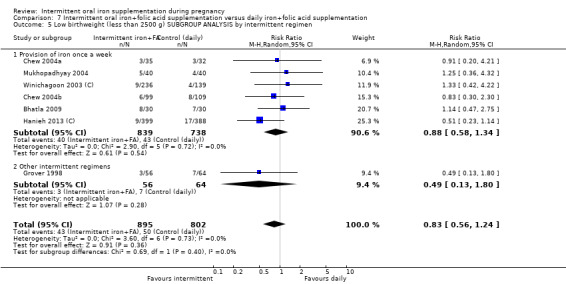

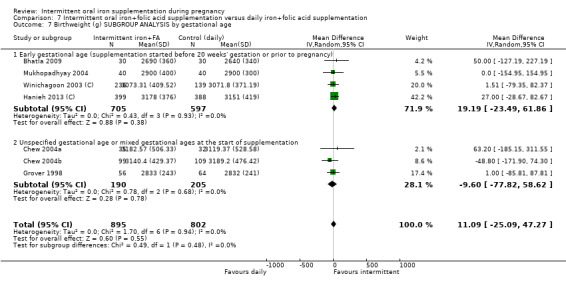

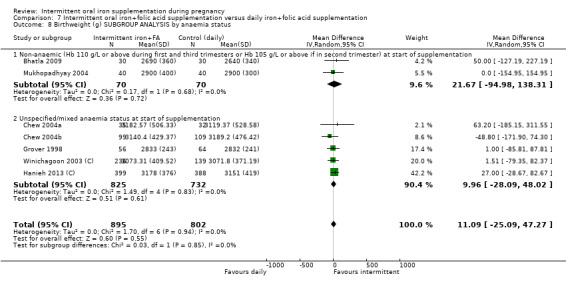

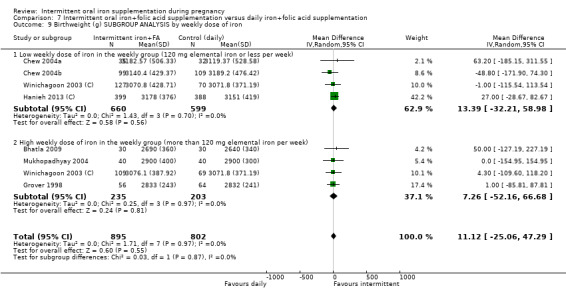

Overall, for women receiving any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with a daily regimen there was no clear evidence of differences between groups for any infant primary outcomes: low birthweight (average risk ratio (RR) 0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.55 to 1.22; participants = 1898; studies = eight; low quality evidence), infant birthweight (mean difference (MD) 5.13 g; 95% CI ‐29.46 to 39.72; participants = 1939; studies = nine; low quality evidence), premature birth (average RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.39; participants = 1177; studies = five; low quality evidence), or neonatal death (average RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.04 to 5.42; participants = 795; studies = one; very low quality). None of the studies reported congenital anomalies.

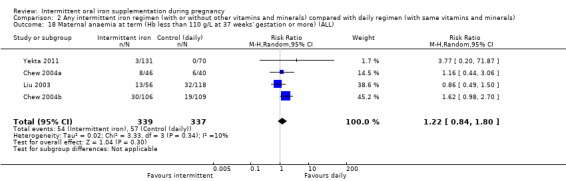

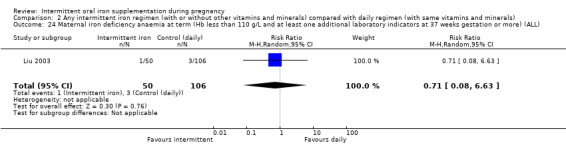

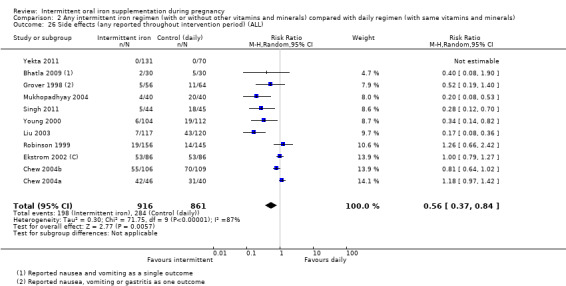

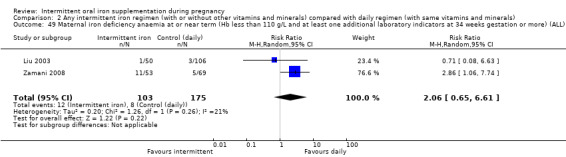

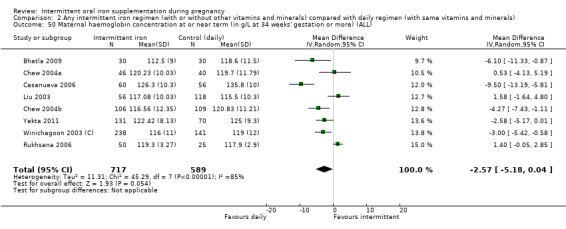

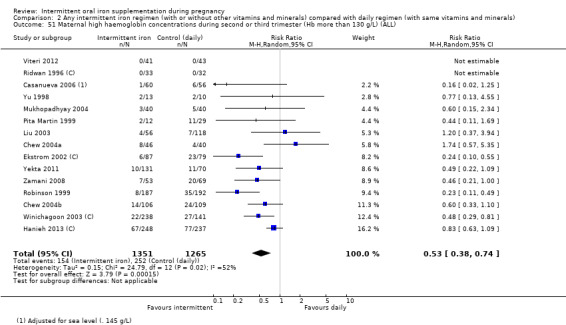

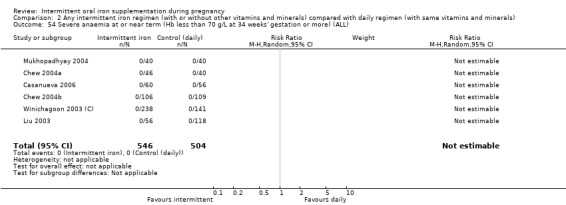

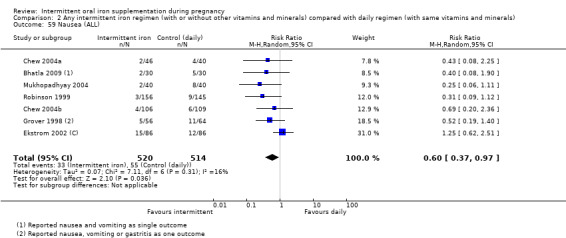

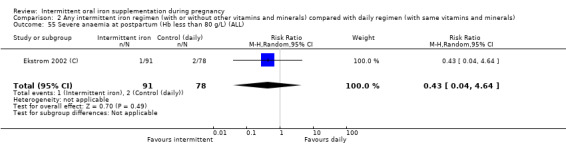

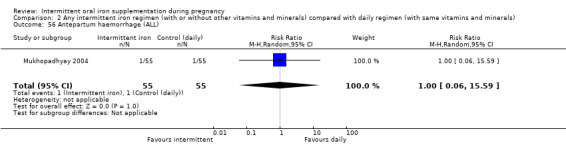

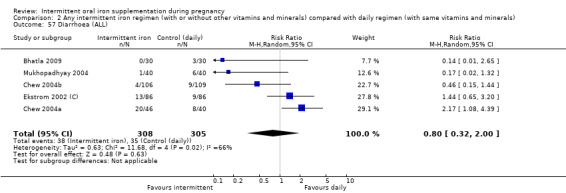

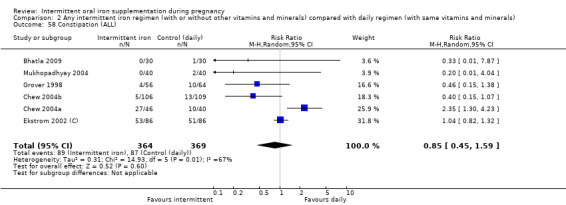

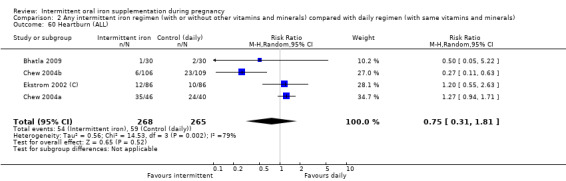

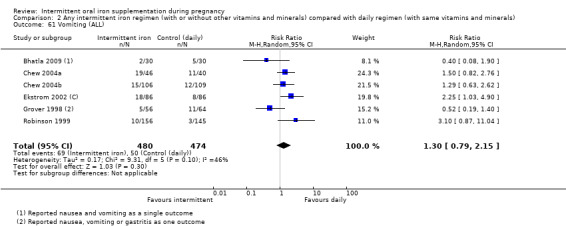

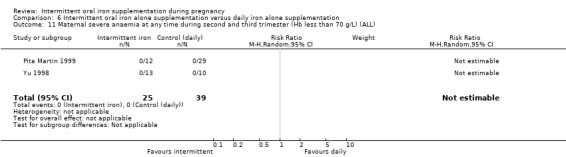

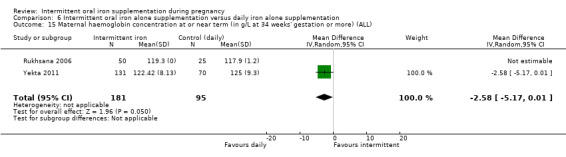

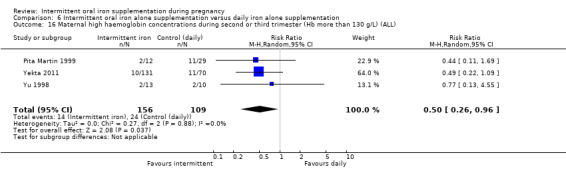

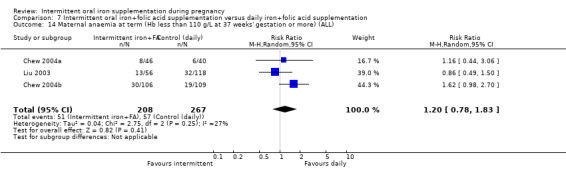

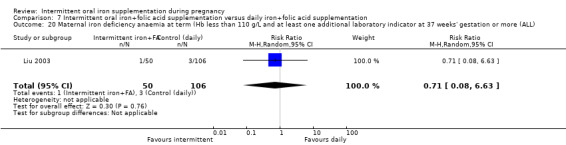

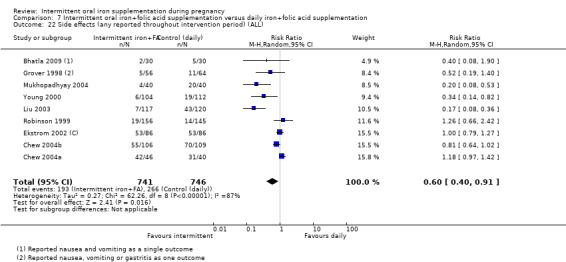

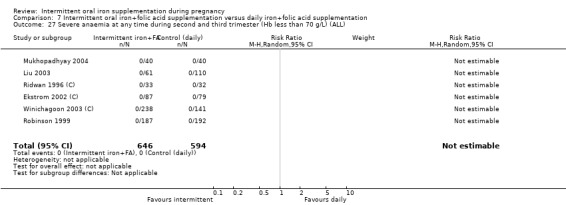

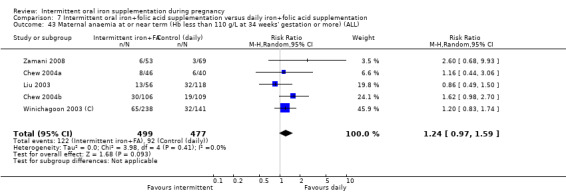

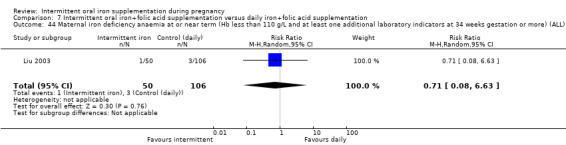

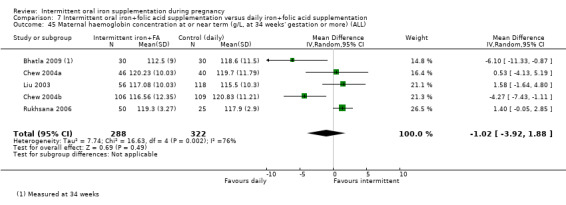

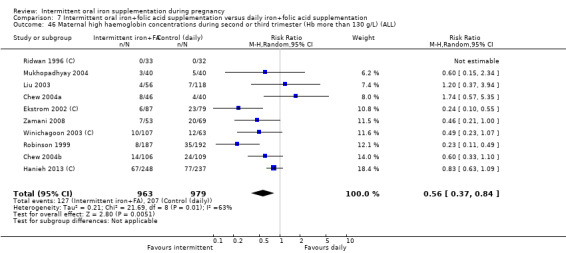

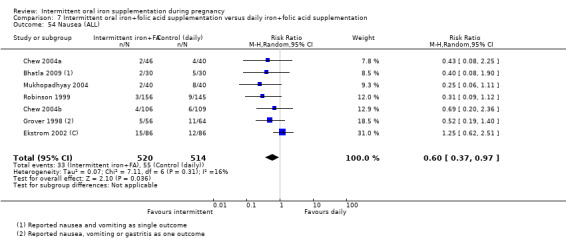

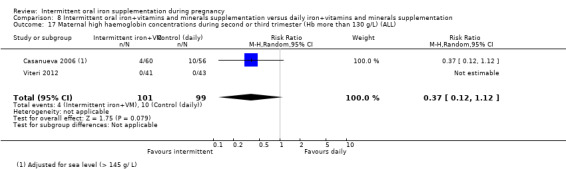

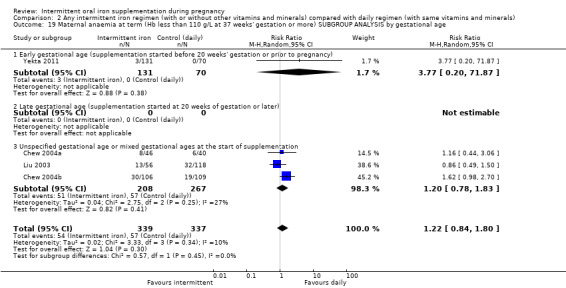

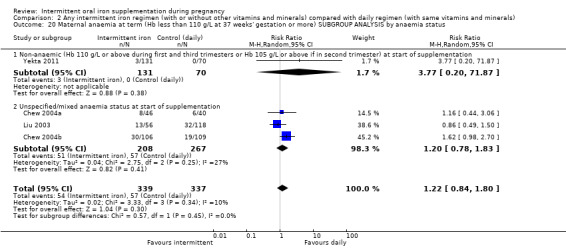

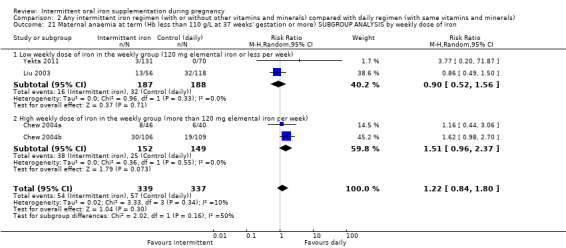

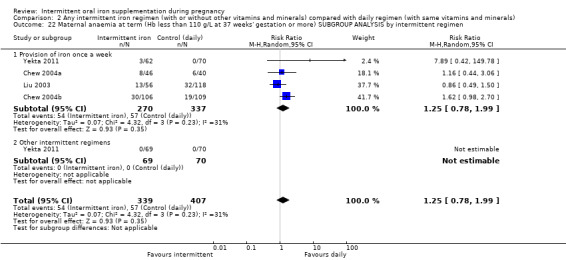

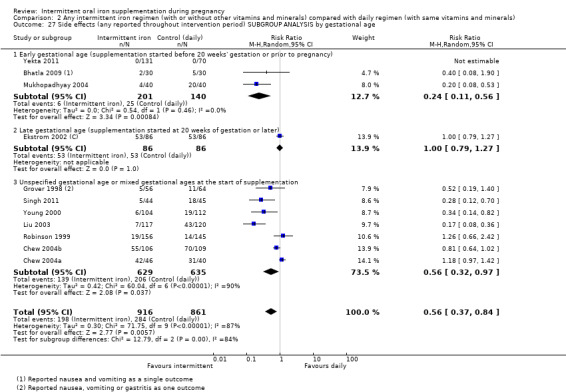

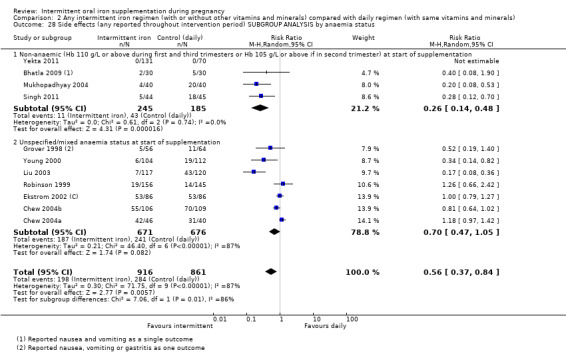

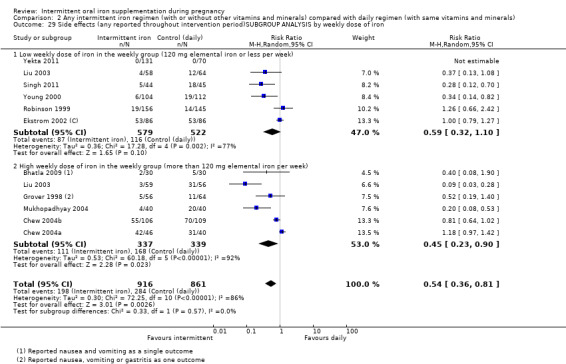

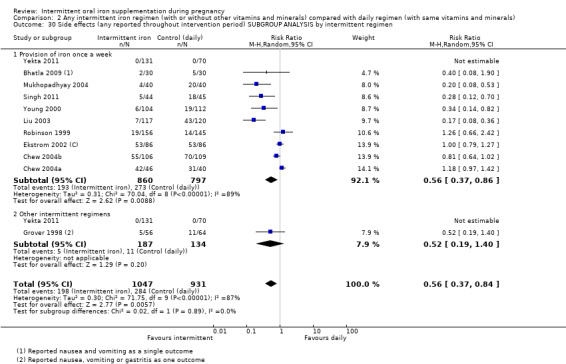

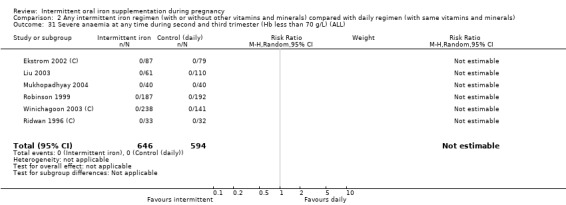

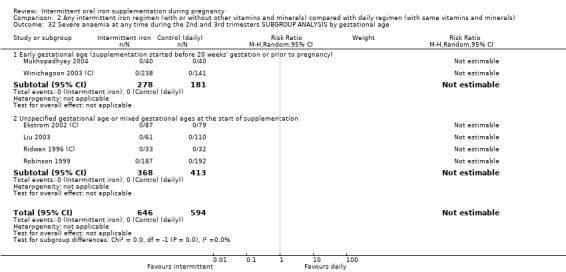

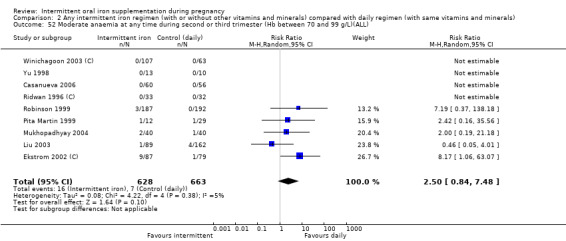

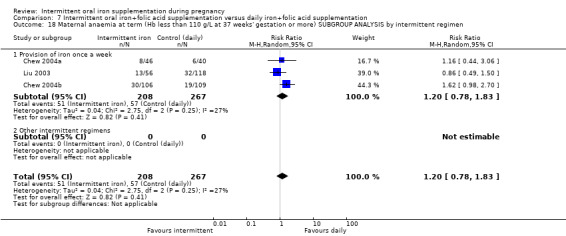

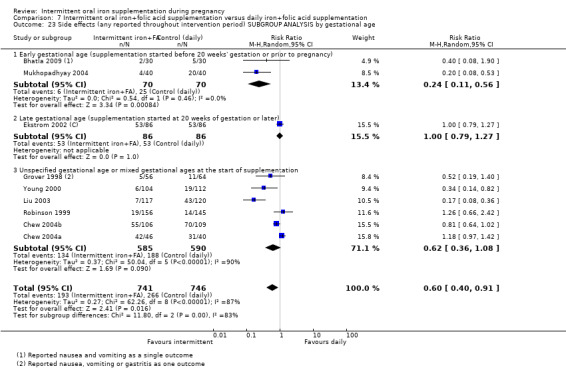

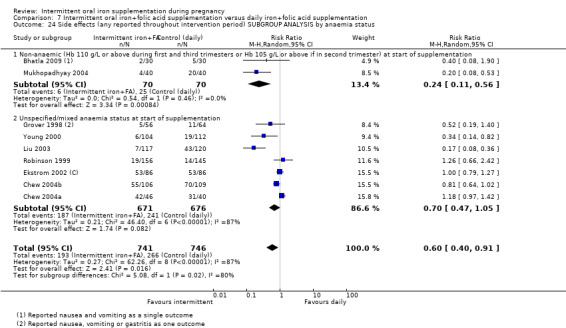

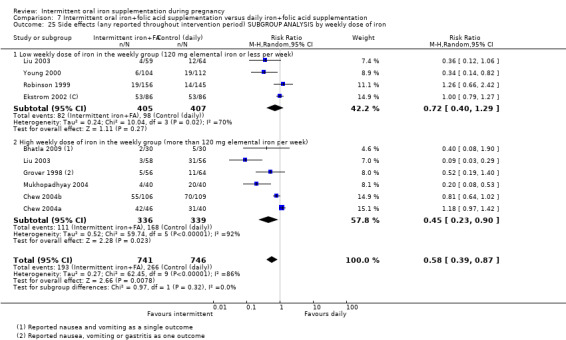

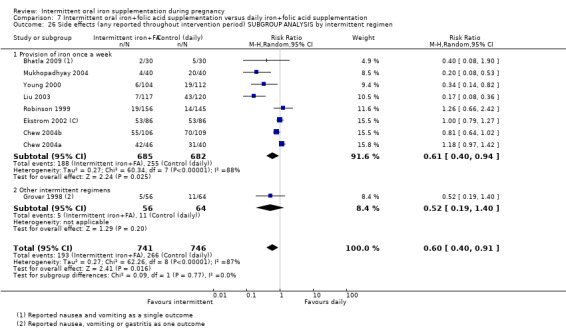

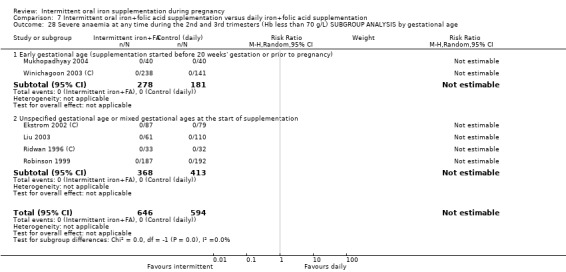

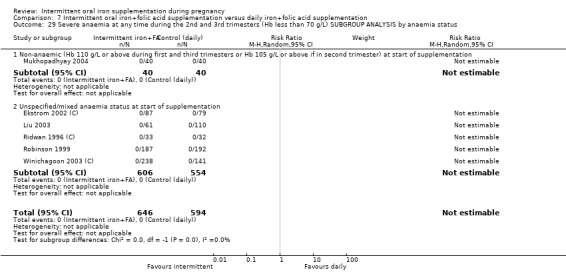

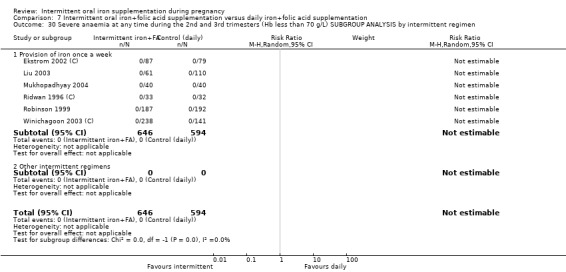

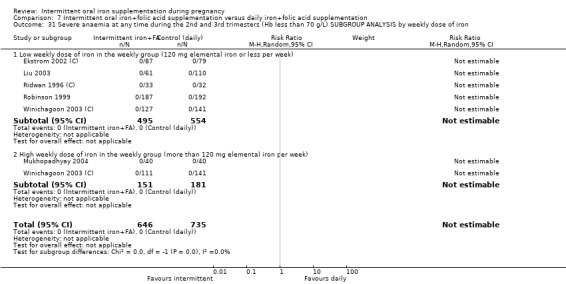

For maternal outcomes, there was no clear evidence of differences between groups for anaemia at term (average RR 1.22; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.80; participants = 676; studies = four; I² = 10%; very low quality). Women receiving intermittent supplementation had fewer side effects (average RR 0.56; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.84; participants = 1777; studies = 11; I² = 87%; very low quality) and were at lower risk of having high haemoglobin (Hb) concentrations (greater than 130 g/L) during the second or third trimester of pregnancy (average RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.74; participants = 2616; studies = 15; I² = 52%; (this was not a primary outcome)) compared with women receiving daily supplements. There were no significant differences in iron‐deficiency anaemia at term between women receiving intermittent or daily iron + folic acid supplementation (average RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.08 to 6.63; participants = 156; studies = one). There were no maternal deaths (six studies) or women with severe anaemia in pregnancy (six studies). None of the studies reported on iron deficiency at term or infections during pregnancy.

Most of the studies included in the review (14/21 contributing data) compared intermittent oral iron + folic acid supplementation compared with daily oral iron + folic acid supplementation (4653 women) and findings for this comparison broadly reflect findings for the main comparison (any intermittent versus any daily regimen).

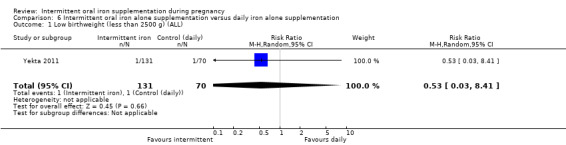

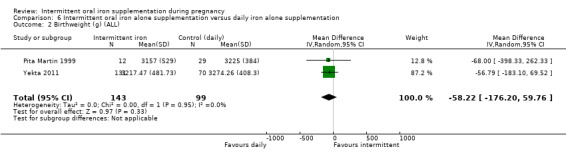

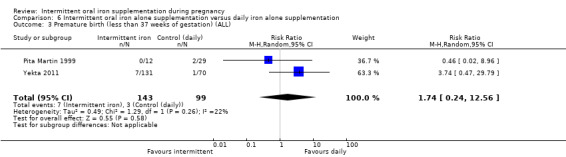

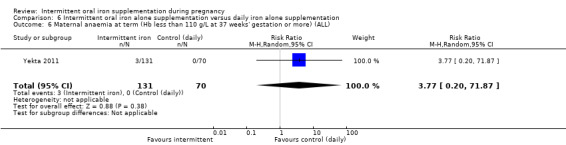

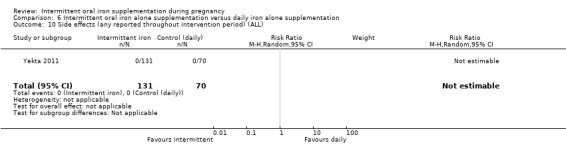

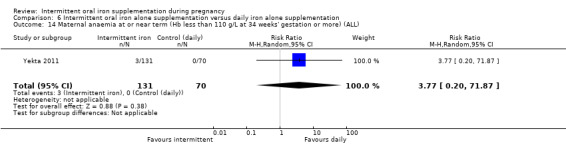

Three studies with 464 women examined supplementation with intermittent oral iron alone compared with daily oral iron alone. There were no clear differences between groups for mean birthweight, preterm birth, maternal anaemia or maternal side effects. Other primary outcomes were not reported.

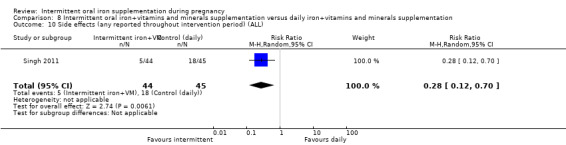

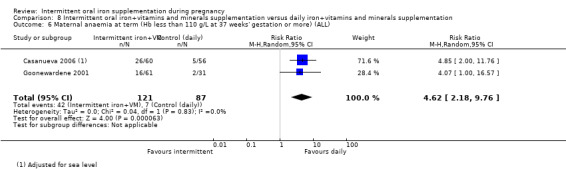

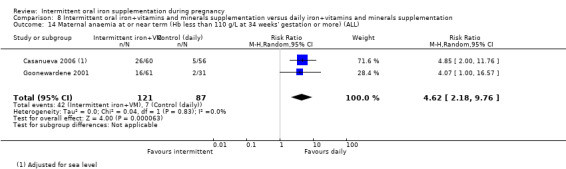

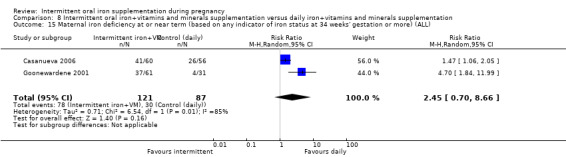

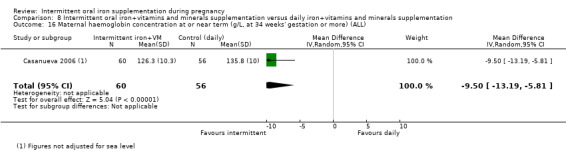

Four studies with a combined sample size of 412 women compared intermittent oral iron + vitamins and minerals supplementation with daily oral iron + vitamins and minerals supplementation. Results were not reported for any of the review's infant primary outcomes. One study reported fewer maternal side effects in the intermittent iron group, and two studies that more women were anaemic at term compared with those receiving daily supplementation.

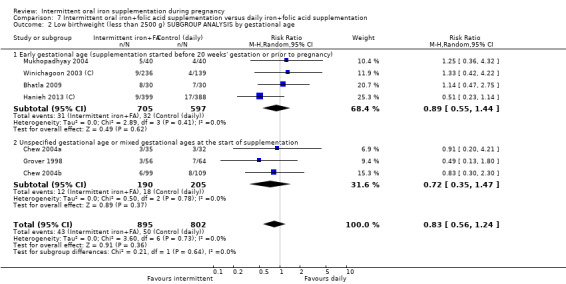

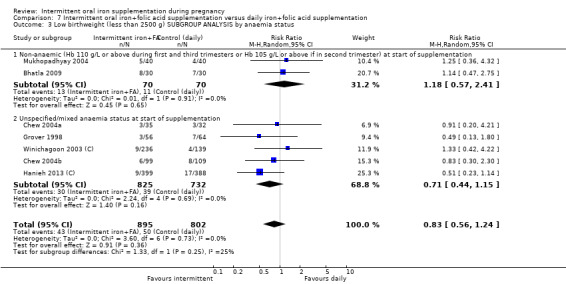

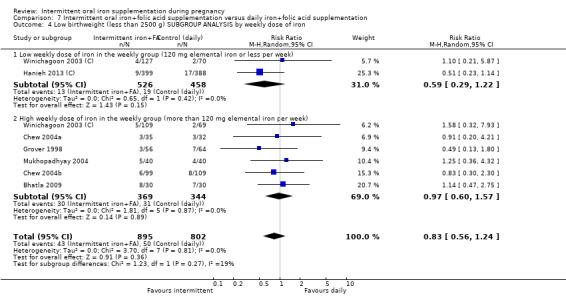

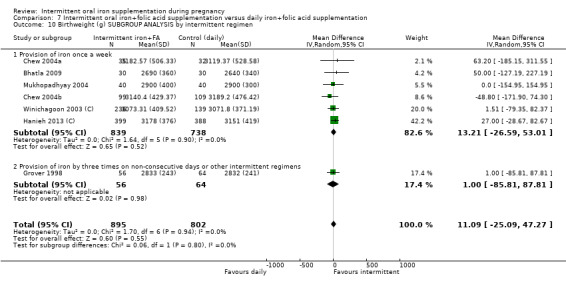

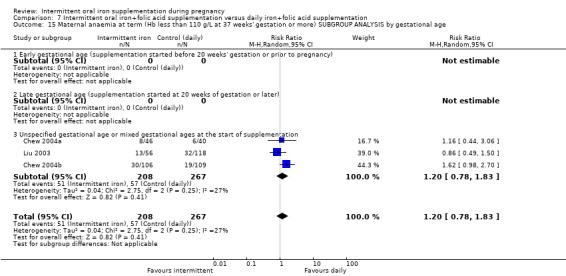

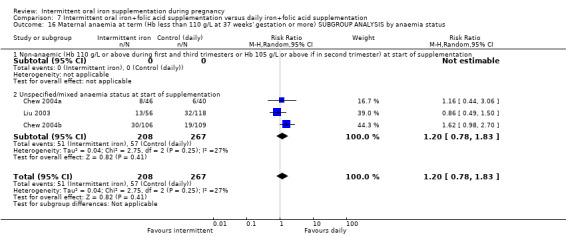

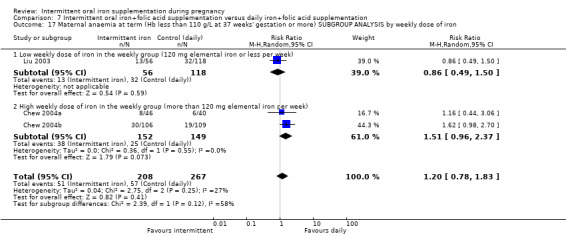

Where sufficient data were available for primary outcomes, we set up subgroups to look for possible differences between studies in terms of earlier or later supplementation; women's anaemia status at the start of supplementation; higher and lower weekly doses of iron; and the malarial status of the region in which the trials were conducted. There was no clear effect of these variables on results.

Authors' conclusions

This review is the most comprehensive summary of the evidence assessing the benefits and harms of intermittent iron supplementation in pregnant women on haematological and pregnancy outcomes. Findings suggest that intermittent regimens produced similar maternal and infant outcomes as daily supplementation but were associated with fewer side effects and reduced the risk of high levels of Hb in mid and late pregnancy, although the risk of mild anaemia near term was increased. While the quality of the evidence was assessed as low or very low, intermittent may be a feasible alternative to daily iron supplementation among those pregnant women who are not anaemic and have adequate antenatal care.

Plain language summary

Intermittent regimens of iron supplementation during pregnancy

Anaemia is a frequent condition during pregnancy, particularly among women from low‐ and middle‐income countries who have insufficient iron intake to meet increased iron needs. Traditionally, pregnancy anaemia has been prevented with the provision of daily iron supplements, however, it has recently been proposed that if women take supplements less often, such as once or twice weekly rather than daily, this might reduce side effects and increase acceptance and adherence to supplementation. In this review we assess the benefits and harms of intermittent (i.e. two or three times a week on non‐consecutive days) oral supplementation with iron or iron + folic acid or iron + vitamins and minerals for pregnant women.

We included 27 randomised controlled trials, but only 21 trials involving 5490 women, had information on the outcomes we evaluated. Three studies looked at intermittent iron alone versus daily iron alone, the other studies included in the review compared intermittent iron combined with folic acid or other vitamins and minerals compared with the same supplements provided daily. Looking at all the studies together (any intermittent regimen including iron versus a daily regimen), there was no clear evidence of differences between groups for most of the outcomes we examined including infant birthweight, premature birth, and perinatal death, or anaemia, haemoglobin concentration and iron deficiency in women at the end of pregnancy. However, women receiving intermittent rather than daily iron supplements were less likely to report side effects (such as constipation and nausea). In addition, intermittent supplementation appeared to decrease the number of women with high haemoglobin concentrations during mid and late pregnancy compared with daily regimens. High haemoglobin concentrations may be harmful as they may be associated with an increased risk of having a premature birth and low birthweight baby. There were no other clear differences between groups for other outcomes examined.

Summary of findings

Background

This review is an update of the published Cochrane review on intermittent oral iron supplementation which suggested that women receiving intermittent iron supplements have similar pregnancy and birth outcomes as those women receiving supplements daily but intermittent supplements are associated with fewer side effects (Peña‐Rosas 2012).

Description of the condition

It is estimated that 38.2% of pregnant women are anaemic worldwide (WHO 2015c), which translates to 32.4 million pregnant women. Half of the global anaemia prevalence is assumed to be due to iron deficiency in non‐malaria areas (Stevens 2013). Other conditions, such as folate, vitamin B12 and vitamin A deficiencies, chronic inflammation, parasitic infections, and inherited disorders can all cause anaemia (WHO 2001). Globally, the prevalence of anaemia has fallen by 12% between 1995 and 2011 (from 33% to 29% in non‐pregnant women and from 43% to 38% in pregnant women), indicating that progress is possible (WHO 2014a).

Anaemia is a condition in which the number of red blood cells or their oxygen‐carrying capacity is insufficient to meet physiological needs, which vary by age, sex, altitude, smoking, and pregnancy status (WHO 2011a). It is associated with impaired cognitive and motor development leading to loss of productivity from impaired work capacity, and also increased susceptibility to infection (Balarajan 2011).

Among all the populations, women are the most susceptible to iron deficiency because of their physiological vulnerability (Masukume 2015). Women of reproductive age are at higher risk of iron‐deficiency anaemia because of physiological processes such as frequent blood loss (due to menstruation), and their increased iron requirements due to pregnancy and breastfeeding. Along with these physiological changes, the presence of parasitic infections and an inadequate iron intake, typical of populations consuming diets that are limited in meat sources, and high in iron absorption inhibitors such as cereals (e.g. wheat, rice or maize), will result in an impairment of the production of red blood cells, resulting in iron‐deficiency anaemia (Suominen 1998). Anaemia during pregnancy is diagnosed if a woman's haemoglobin (Hb) concentration at sea level is lower than 110 g/L, although it is recognised that during the second trimester of pregnancy, Hb concentrations diminish by approximately 5 g/L (WHO 2011a). When anaemia is accompanied by an indicator of iron deficiency (e.g.low concentrations of serum transferrin receptor, or low ferritin concentrations), it is referred to as iron‐deficiency anaemia (Walsh 2011; WHO 2011a; WHO 2011b). However, the use of a ferritin cut‐off in various populations, particularly those living in settings where inflammation is common is being updated (Garcia‐Casal 2014). Ferritin concentration is usually measured, but it is not a sensible indicator during pregnancy (WHO 2011b). Iron deficiency alone is almost 2.5 times higher than iron‐deficiency anaemia and iron deficiency alone can lead to impairment of tissue development (Goonewardene 2012).

Pregnant women have augmented iron requirements because of rapid tissue growth, the expansion of red cell mass and increasing fetal needs. During the second half of the pregnancy there is a notable increase of iron requirements due to the expansion of the red blood cell mass and the transfer of increasing amounts of iron to both the growing fetus and the placental structure. The amount of iron needed during pregnancy depends on the iron stores before pregnancy, i.e. women may develop iron‐deficiency anaemia due to the fact that iron stores were not sufficient to meet increased needs (Bothwell 2000; Viteri 2005).

It is estimated that most pregnant women would need additional iron in their diets as well as sufficient iron stores (500 mg of iron or more) to prevent iron deficiency (Bothwell 2000; IOM 2001). Low Hb levels during pregnancy, indicative of moderate or severe anaemia, are associated with increased risk of low birthweight, maternal and child mortality, and infectious diseases (INACG 2002). Children born to anaemic mothers are more likely to be anaemic early in life and it has been reported that iron deficiency may irreversibly affect the cognitive performance and development and physical growth of infants (WHO 2001) even in the long term (Gleason 2007; Lozoff 2006; Lozoff 2007; Burke 2014). During pregnancy, the growing fetus is in a vulnerable state and is entirely dependent on the mother and the maternal environment for its nutritional requirements, and it has been suggested that the consequences of inappropriate nutrition in utero can extend into adulthood, a phenomenon known as fetal programming (Andersen 2006). Studies with rats have suggested that iron deficiency during the fetal period resulted in smaller offspring, with smaller kidneys, both in absolute and proportional terms, and an enlarged heart, all which may be associated with hypertension later in life (Andersen 2006; McArdle 2006). The plausibility of this theory, however, needs to be confirmed by epidemiological studies.

There appears to be a U‐shape optimal range for Hb levels during pregnancy, as high Hb concentrations (greater than 130 g/L at sea level) also increase the risk of non‐desirable pregnancy outcomes, including low birthweight and premature birth (Casanueva 2003b; Hytten 1964; Hytten 1971; Murphy 1986; Scholl 1997; Steer 2000). Although the mechanisms for this are far from being elucidated, a low plasma volume appears to precede late pregnancy hypertension, which in turn is associated with low birthweight small‐for‐gestational‐age babies (Gallery 1979; Goodlin 1981; Huisman 1986; Koller 1979; Silver 1998). However, these findings are still inconsistent (Gallery 1979; Hytten 1971; Hytten 1985; Koller 1979; Letsky 1991; Poulsen 1990), and it has been hypothesised that high Hb concentrations increase blood viscosity, with or without a change in the plasma volume, and reduce placental perfusion, leading possibly to placental/fetal hypoxia (Erslev 2001; LeVeen 1980).

Description of the intervention

Intermittent oral iron supplementation (i.e. one, two or three times a week on non‐consecutive days) is recommended as an alternative to daily iron supplementation during pregnancy in non‐anaemic pregnant women (WHO 2012). The rationale for intermittent iron administration is based on two lines of evidence: the first one is related to the concept that exposing intestinal cells to supplemental iron less frequently, (e.g. every week in synchrony with the human mucosal turnover that occurs every five to six days) may improve the efficiency of absorption since the mucosal cells are not "blocked" by large amounts of iron as may occur with daily iron intake (Anderson 2005; Frazer 2003a; Frazer 2003b). The second line is related to the fact that daily iron supplementation, by maintaining an iron‐rich environment in the gut lumen and in the intestinal mucosal cells, produces oxidative stress and is prone to increasing the severity and frequency of undesirable side effects (Srigiridhar 1998; Srigiridhar 2001; Viteri 1997; Viteri 1999a).The side effects are probably caused by the challenges of having to cope with a large non‐physiologic bolus dose of iron, which may also contribute to adverse interactions with infectious diseases including malaria. Ideally, less side effects would lead to a higher adherence to supplementation (Viteri 1995; Viteri 1999b), however, some authors have questioned this belief, indicating that the main reason for the poor compliance with programmes is the unavailability of iron supplements for the targeted women (Galloway 1994). The intervention could be an effective strategy in addressing the problem of forgetfulness and to improve supplementation compliance (Goonewardene 2012).

An important consideration when providing supplemental iron is the presence of malaria. Approximately 40% of the world population is exposed to the parasite and it is endemic in over 100 countries (WHO 2011d) and more than 85 million pregnancies occur in areas with some degree of Plasmodium falciparum transmission (Dellicor 2010). It is estimated that about 15 million pregnant women remain without access to preventive treatment for malaria (WHO 2014d). Of all the complications associated with this disease, anaemia is the most common and causes the highest number of malaria‐related deaths. This parasite causes anaemia by the haemolysis of red blood cells and the compounding suppression of erythropoiesis (Darnton‐Hill 2007). Malaria in pregnant woman and placental malaria increases the risk of maternal death, miscarriage, stillbirth and low birthweight with associated risk of neonatal death (WHO 2011d; WHO 2011e). Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) (i.e. administration of sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine during the second and third trimester of pregnancy) can reduce severe maternal anaemia (WHO 2014d) and is recommended in malaria‐endemic areas at each scheduled antenatal care (ANC) visit for protection against malaria. There is evidence that high doses of folic acid (i.e. 5000 μg or more) may interfere with the efficacy of sulfadoxine‐pyrimethamine as an antimalarial (Roll Back Malaria Partnership 2015).

Provision of iron in malaria‐endemic areas has been a long‐standing controversy due to concerns that iron therapy may exacerbate infections, in particular malaria (Oppenheimer 2001). Although the mechanisms by which additional iron can benefit the parasite are far from clear (Prentice 2007), the use of daily iron supplementation has been limited in programme settings, possibly due to a lack of compliance, concerns about the safety of the intervention among women with an adequate iron intake, and variable availability of the supplements at community level.

How the intervention might work

Screening for iron stores and anaemia in pregnant women usually start in early or mid pregnancy (approximately < 20 weeks of gestational age) (Bencaiova 2012), and provision of daily oral iron with folic acid supplements for pregnant women has been used extensively in prenatal care programmes in low‐ and middle‐income countries as an intervention to prevent and correct iron deficiency and anaemia during pregnancy (Beard 2000; Haider 2013; Villar 1997). Although iron supplementation with or without folic acid has been used in a variety of doses and regimens, current recommendations for pregnant women include the provision of a standard daily dose of 30 to 60 mg of elemental iron and 400 μg (0.4 mg) of folic acid starting as early as possible (WHO 2012a). If at six months of treatment, the ideal Hb concentrations cannot be achieved during pregnancy, either continued supplementation during the postpartum period or increased dosage to 120 mg iron daily during pregnancy should be given (WHO 2012a). Optimal concentrations of red cell folate concentrations have been also proposed with an minimum serum concentration 400 mg/mal or 906 nmol/L) in order to reduce the risk of neural tube defects on children (WHO 2015a).

Currently, the World Health Organization has made recommendations for intermittent iron supplementation intake in non pregnant women of reproductive age and pregnant women. For women in reproductive age, weekly supplementation with 60 mg of elemental iron plus 2800 μg (2.8 mg) of folic acid (WHO 2011c) in populations where the prevalence of anaemia is above 20%. In addition to increasing iron stores, this intervention represents an opportunity to improve folate status before pregnancy and in the very early stages of pregnancy, particularly for those women who may become pregnant or do not know they are already pregnant and are not covered by other programmes as many pregnancies are not planned (WHO 2011c). For non‐anaemic pregnant women, WHO recommends a weekly supplementation of 120 mg of elemental iron plus 2800 μg (2.8 mg) of folic acid when anaemia is lower than 20% in order to prevent anaemia and improve gestational outcomes (WHO 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

Anaemia in pregnancy is a major public health and economic problem (Pasricha 2013). Daily oral supplementation in pregnant women has been a long‐standing, cost‐effective recommended intervention both in the public health and clinical fields (WHO 2012a). However, adherence to daily iron and folic acid supplementation still faces challenges. Data from national surveys from 46 countries (2003 to 2009) indicate that about 52% to 75% of mothers receive any iron tablets during pregnancy, and the duration of supplementation is usually short (Lutter 2011).This may be due to poor distribution of pills, distressing side effects experienced by women or safety concerns related to the routine use of iron supplements in areas where anaemia is not of public health problem or by women who are not anaemic.

The findings of this review will update the previous version of intermittent oral iron supplementation during pregnancy (Peña‐Rosas 2012), which suggested that women receiving intermittent iron supplements have similar pregnancy and birth outcomes as those women receiving supplements daily. This review also suggested that women receiving daily supplements had increased risk of developing high levels of Hb in mid and late pregnancy but were less likely to present mild anaemia near term.

The present review will complement those from other Cochrane reviews assessing the effects and safety of daily iron and iron plus folic acid supplementation during pregnancy (Peña‐Rosas 2015). Other reviews assessing the effects of supplementing pregnant women with different vitamins and minerals include: the effectiveness of different iron therapies for pregnant women with a diagnosis of anaemia attributed to iron deficiency (Reveiz 2011), the effects of supplementation with vitamin A during pregnancy (van den Broek 2010), zinc supplementation in pregnancy (Ota 2015), vitamin C supplementation in pregnancy (Rumbold 2015). The effectiveness of oral folate supplementation alone during pregnancy on haematological and biochemical parameters and on pregnancy outcomes (Lassi 2013), the effects and safety of periconceptional folate supplementation for preventing congenital anomalies (De‐Regil 2010), the effects of multiple vitamin and mineral supplements during pregnancy (Haider 2012), the effects of point‐of‐use fortification with micronutrient powders for women in pregnancy (Suchdev 2011; Suchdev 2015), are evaluated in related reviews.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of intermittent oral supplementation with iron alone or in combination with folic acid or other vitamins and minerals to pregnant women on neonatal and pregnancy outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised trials with randomisation either at individual or cluster level. We did not include cross‐over trials or any observational study designs (for example, cohort or case‐control studies) in the meta‐analysis, but we have considered such evidence in the discussion where relevant.

Types of participants

Pregnant women of any gestational age and parity with confirmed pregnancy at the moment of randomisation. Studies specifically targeting women with diagnosed health problems, for example HIV or tuberculosis were excluded.

Types of interventions

Oral supplements of iron, or iron + folic acid, or iron + vitamins and minerals, given as a public health strategy on an intermittent basis and compared with a placebo or no supplementation, or compared with the same supplements provided daily. We excluded studies dealing specifically with iron therapies for anaemic women as a part of clinical practice.

Oral iron supplementation refers to the delivery of iron compounds directly to the oral cavity, either as a tablet (dispersible or not), capsule, or liquid. For the purpose of this review, intermittent supplementation is defined as the provision of iron supplements one, two or three times a week on non‐consecutive days.

We performed the following comparisons.

Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with no supplementation or placebo.

Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals).

Intermittent oral iron alone supplementation compared with no supplementation or placebo.

Intermittent oral iron + folic acid supplementation compared with no supplementation or placebo.

Intermittent oral iron + vitamins and minerals supplementation compared with no supplementation or placebo.

Intermittent oral iron alone supplementation compared with daily oral iron supplementation.

Intermittent oral iron + folic acid supplementation compared with daily oral iron + folic acid supplementation.

Intermittent oral iron + vitamins and minerals supplementation compared with daily oral iron + vitamins and minerals supplementation.

Interventions that combined iron supplementation with co‐interventions such as education or other approaches were included only if the other co‐interventions were the same in both the intervention and comparison groups. We excluded studies examining tube feeding, parenteral nutrition or supplementary food‐based interventions such as mass fortification of staple or complementary foods, point‐of‐use fortification with micronutrient powders, lipid‐based supplements or Foodlets tablets, or biofortification.

Types of outcome measures

Maternal, perinatal and postpartum clinical and laboratory outcomes and infant clinical and laboratory outcomes as described below.

Primary outcomes

Infant

Low birthweight (less than 2500 g).*

Birthweight (g).*

Premature birth (less than 37 weeks' gestation).*

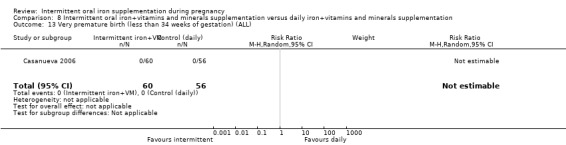

Neonatal death (within 28 days after delivery).*

Congenital anomalies, including neural tube defects (as defined by trialists).*

Maternal

Maternal anaemia at term (Hb less than 110 g/L at 37 weeks' gestation or more).*

Maternal iron deficiency at term (as defined by trialists, based on any indicator of iron status at 37 weeks' gestation or more).*

Maternal iron‐deficiency anaemia at term ((Hb less than 110 g/L and at least one additional laboratory indicator at 37 weeks' gestation or more).*

Maternal death (death while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy).*

Side effects (any reported throughout intervention period).*

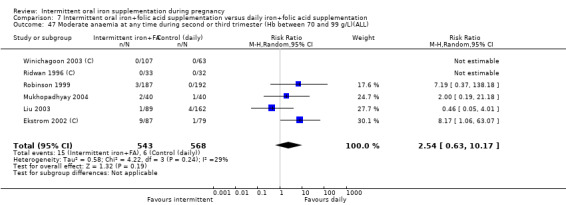

Severe anaemia at any time during second or third trimesters (Hb less than 70 g/L).*

Clinical malaria (as defined by trialists).*

Infection during pregnancy (including urinary tract infections and others as specified by trialists).*

* Outcomes that are included in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Secondary outcomes

Infant

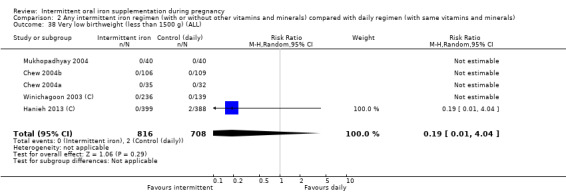

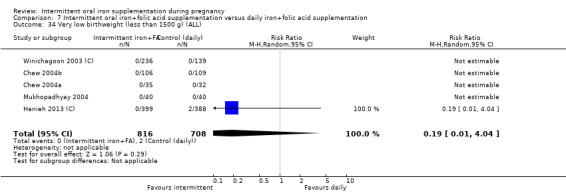

Very low birthweight (less than 1500 g).

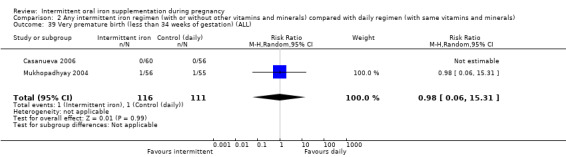

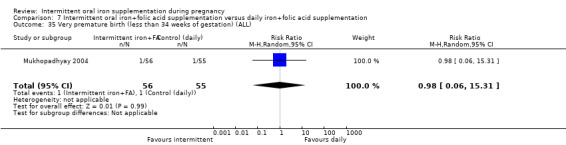

Very premature birth (less than 34 weeks' gestation).

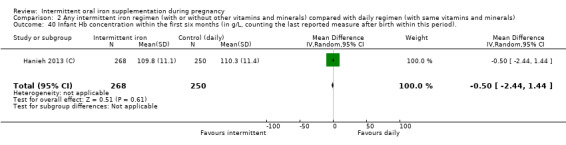

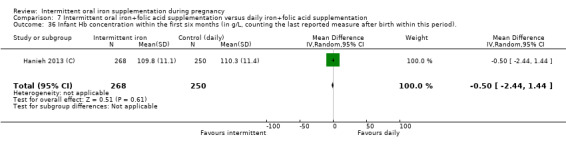

Hb concentration within the first six months (in g/L, counting the last reported measure after birth within this period).

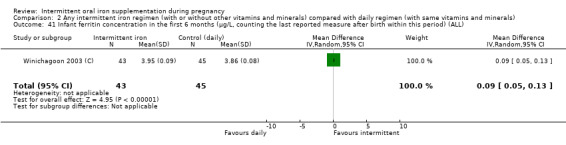

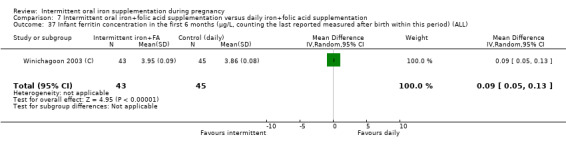

Ferritin concentration within the first six months (in μg/L, counting the last reported measure after birth within this period).

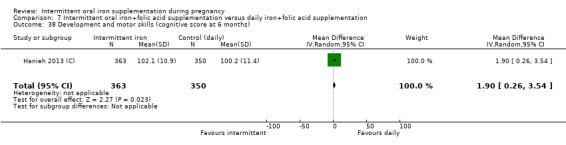

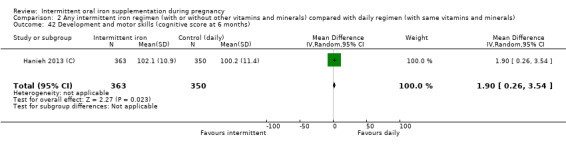

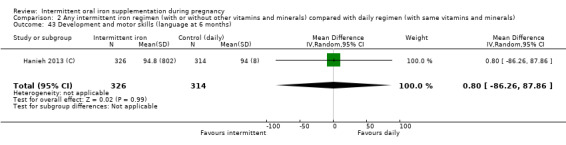

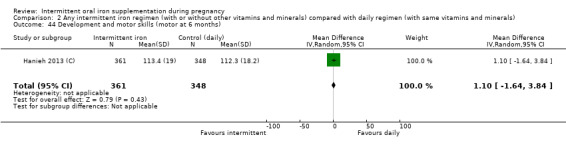

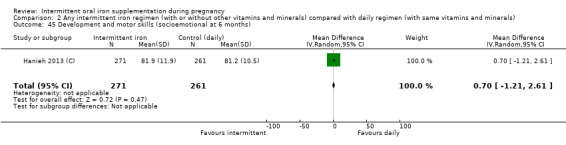

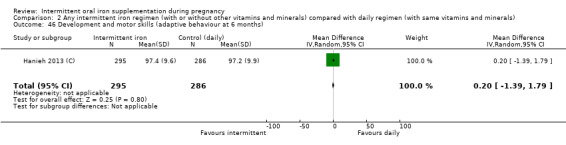

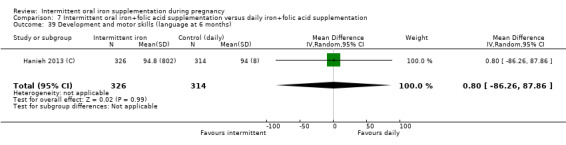

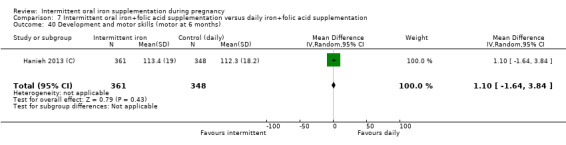

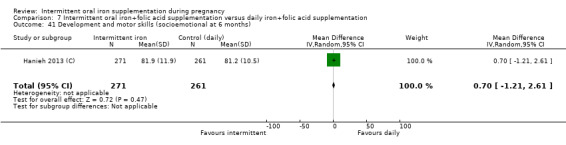

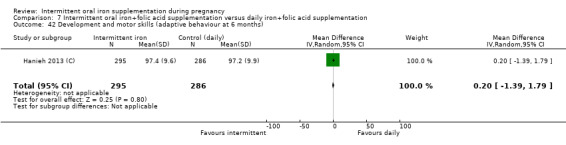

Development and motor skills (as defined by trialists).

Admission to special care unit.

Maternal

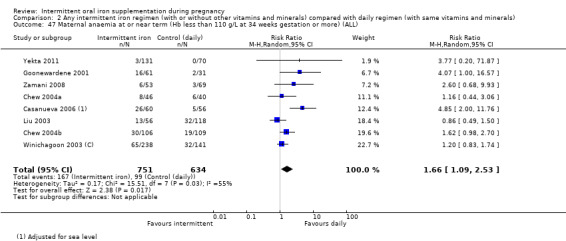

Maternal anaemia at or near term (Hb less than 110 g/L at 34 weeks' gestation or more).

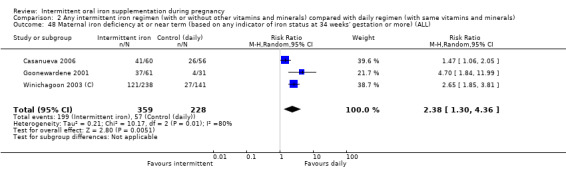

Maternal iron deficiency at or near term (as defined by trialists, based on any indicator of iron status at 34 weeks' gestation or more).

Maternal iron‐deficiency anaemia at or near term ((Hb less than 110 g/L and at least one additional laboratory indicator at 34 weeks' gestation or more).

Maternal Hb concentration at or near term (in g/L, at 34 weeks' gestation or more).

Maternal Hb concentration within one month postpartum in g/L.

Maternal high Hb concentrations at any time during second or third trimester (defined as Hb greater than 130 g/L).

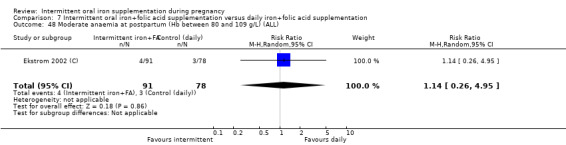

Moderate anaemia at postpartum (Hb between 80 and 109 g/L).

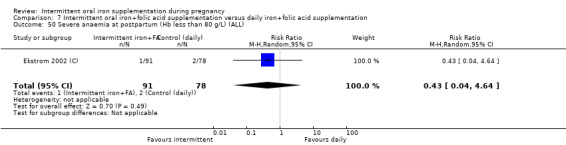

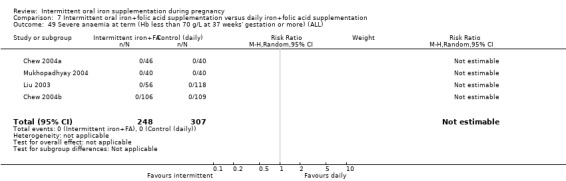

Severe anaemia at term (Hb less than 70 g/L at 37 weeks' gestation or more).

Severe anaemia at or near term (Hb less than 70 g/L at 34 weeks' gestation or more).

Severe anaemia postpartum (Hb less than 80 g/L).

Puerperal infection (as defined by trialists).

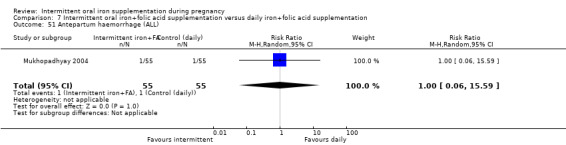

Antepartum haemorrhage (as defined by trialists).

Postpartum haemorrhage (intrapartum and postnatal, as defined by trialists).

Transfusion given (as defined by trialists).

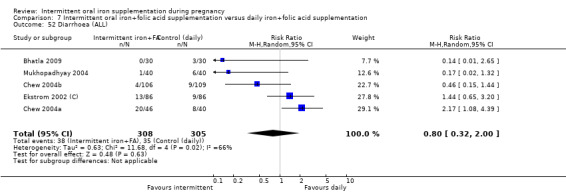

Diarrhoea (as defined by trialists).

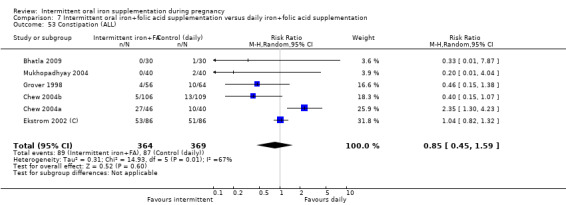

Constipation (as defined by trialists).

Nausea (as defined by trialists).

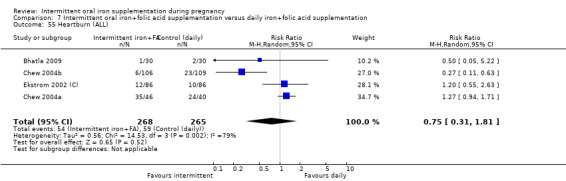

Heartburn (as defined by trialists).

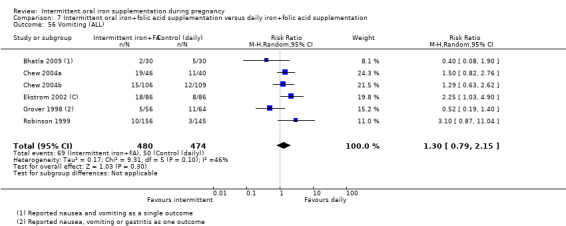

Vomiting (as defined by trialists).

Maternal well being/satisfaction (as defined by trialists).

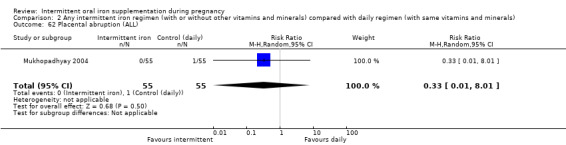

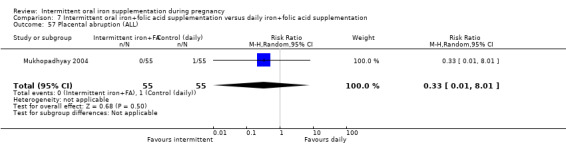

Placental abruption (as defined by trialists).

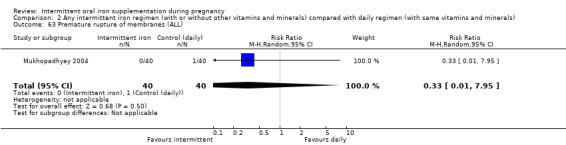

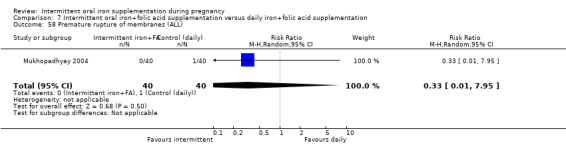

Premature rupture of membranes (as defined by trialists).

Pre‐eclampsia (as defined by trialists).

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (31 July 2015).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We also searched the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) for any ongoing or planned trials on (31 July 2015) using the search terms described in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

For assistance in identifying ongoing or unpublished studies, we also contacted the Departments of Reproductive Health and Research and Nutrition for Health and Development from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the nutrition sections of the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme (WFP), the Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Micronutrient Initiative (MI), the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), Hellen Keller International (HKI), and Sight and Life (31 July 2015).

We did not apply any date or language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seePeña‐Rosas 2012.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing the reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

In this update, two review authors (Heber Gomez Malave (HGM) and Monica Flores Urrutia (MFU)) independently assessed and selected the trials for inclusion in the review. Any disagreement on trial eligibility was resolved by discussion or Juan Pablo Peña‐Rosas (JPPR) served as arbiter.

It was not possible for us to assess the relevance of the trials in a blinded manner because we knew the authors' names, institution, journal of publication and results when we applied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to facilitate the process of data extraction and to request additional (unpublished) information from the authors of the original reports. We resolved any disagreements by discussion, and, if necessary, sought clarification from the authors of the original reports.

We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked them for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Review authors LMD, TD or JPPR independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Each trial was assessed by two review authors. We resolved any disagreement by discussion.

For this update, 2015, we have assessed blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) and blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias) separately, as specified in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

(1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We have described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence. We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We have described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes);

unclear.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance)

We have described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. For this type of intervention, where different regimens were compared, it would be theoretically possible to blind study participants and staff by providing both active and placebo tablets to women allocated to intermittent regimens and placebo tablets to women in no supplementation arms of trials.

Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes and we have noted where there was partial blinding.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We have described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We assessed losses to follow‐up and post‐randomisation exclusions systematically for each trial.

We have described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We have noted whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. We assessed methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

We considered follow‐up to be adequate (low risk of bias) if at least 80% of participants initially randomised in a trial were included in the analysis and any loss was balanced across groups, unclear if the percentage of initially randomised participants included in the analysis was unclear or not stated, and high risk of bias if less than 80% of those initially randomised were included in the analysis.

(5) Selective reporting bias

We have described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review had been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s prespecified outcomes had been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; or the study failed to include results of a key outcome that we would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

(6) Other sources of bias

We have noted for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low, high or unclear risk for other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We summarised the risk of bias at two levels: within studies (across domains) and across studies.

For the first, we made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. Attrition, lack of blinding and losses to follow‐up may be particular problems in studies looking at different regimens of iron supplementation and where women are followed up over time. We explored the impact of the level of bias by undertaking sensitivity analyses, seeSensitivity analysis below.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we present results as average risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

For continuous outcomes we present the results as mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs. There was no need to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials as these outcomes were measured with the same methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We included cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. Cluster‐randomised trials are labelled with a (C). We estimated the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) from trials' original data sets and reported the design effect (Higgins 2011). We estimated the ICCs for Hb from Ridwan 1996 (C) (ICC 0.05; average cluster size 23.1; design effect 2.1) and Winichagoon 2003 (C) (ICC 0.03; average cluster size 31.6; design effect 2.09). In the trial by Ekstrom 2002 (C), trial authors reported that they had adjusted the results by initial Hb measurements as well as by clustering effect within participants and thus we did not carry out any additional adjustment. For the Hanieh 2013 (C) trial, ICCs for all outcomes reported were provided by the authors, and we used these to calculate the cluster design effect for each outcome.

We considered that it was reasonable to combine the results from both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials as there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely.

Cross‐over trials

The study by (Viteri 2012) was included but only for the period of 20 to 28 weeks. Women in this study were changed to the other group and thus not useful for our study purposes. The characteristics of this study are described in the Characteristics of included studies.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, levels of attrition have been noted in the Characteristics of included studies tables. We explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by carrying out sensitivity analysis (these same trials were assessed as being at high risk of bias, seeSensitivity analysis below).

Where possible, we conducted an available case analysis and reinstated previously excluded cases, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial being the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined the forest plots from the analyses visually to assess any obvious heterogeneity in terms of the size or direction of treatment effect between studies. We used the I², and Tau² statistics and the P value of the Chi² test for heterogeneity to quantify heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. The I² statistic quantifies inconsistency and describes the percentage of the variability in effect estimate that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance). We considered that heterogeneity was substantial or high if the I² exceeded 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We generated funnel plots in RevMan 2014 for those few outcomes with 10 trials or more. We did not find a clear indication of asymmetry.

Where we suspected reporting bias (seeSelective reporting (reporting bias) above), we attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by a sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014).

Because of our experience in conducting other reviews in this area, we anticipated high heterogeneity among trials, and we pooled trial results using a random‐effects model and were cautious in our interpretation of the pooled results. In the text, for statistically significant results, we have given the values of I², Tau² and the P value of the Chi² test for heterogeneity, and have indicated that the random‐effects model gives the average treatment effect. For analyses where there are high levels of heterogeneity, we have provided an estimate of the 95% range of underlying intervention effects (prediction interval).

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using GRADE

For the assessment across studies, we used the GRADE approach to interpret findings as outlined in the GRADE handbook, and the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool allowed us to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) to create 'Summary of findings' tables set out in Table 1 and Table 2 (SoF). The primary outcomes for the main comparison have been listed with estimates of relative effects along with the number of participants and studies contributing data for those outcomes. These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall quality of evidence from studies included in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the outcomes we considered. For each individual outcome, the quality of the evidence was assessed independently by two review authors using the GRADE approach (Balshem 2010).

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals)‐infant outcomes.

| Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals)‐ infant outcomes | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Women receiving supplements during pregnancy

Settings: Community settings

Intervention: Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals) Comparison: Daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals) | Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) | |||||

| Low birthweight (less than 2500 g) | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.55 to 1.22) | 1898 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | ||

| 58 per 1000 | 48 per 1000 (32 to 71) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 131 per 1000 | 108 per 1000 (72 to 160) | |||||

| Birthweight (g) | The mean birthweight (g) in the intervention group was 5.13 g more (29.46 g less to 39.72 g more) | MD 5.13 (‐29.46 to 39.72) | 1939 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | ||

| Premature birth (less than 37 weeks of gestation) | Study population | RR 1.03 (0.76 to 1.39) | 1177 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1,2 | ||

| 128 per 1000 | 131 per 1000 (97 to 177) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 162 per 1000 | 167 per 1000 (123 to 225) | |||||

| Neonatal death (within 28 days after delivery) | Study population | RR 0.49 (0.04 to 5.42) | 795 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3,4 | ||

| 5 per 1000 | 2 per 1000 (0 to 27) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 5 per 1000 | 2 per 1000 (0 to 28) | |||||

| Congenital anomalies (including neural tube defects) | Study population | (0 studies) | Not reported | |||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Several studies contributing data had serious design limitations

2Wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect

3Single study with some design limitations contributing data

4Wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect, few events.

Summary of findings 2. Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals)‐maternal outcomes.

| Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals)‐ maternal outcomes | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Women receiving supplements in pregnancy

Settings: Community settings

Intervention: Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) Comparison: Daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Daily regimen (with same vitamins and minerals) | Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) | |||||

| Maternal anaemia at term (Hb less than 110 g/L at 37 weeks' gestation or more) | Study population | RR 1.22 (0.84 to 1.80) | 676 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1,2 | ||

| 169 per 1000 | 206 per 1000 (142 to 304) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 162 per 1000 | 198 per 1000 (136 to 292) | |||||

| Maternal iron deficiency at term (based on any indicator of iron status at 37 weeks' gestation or more) | Study population | (0 studies) | Not reported | |||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Maternal iron‐deficiency anaemia at term (Hb less than 110 g/L and at least 1 additional laboratory indicators at 37 weeks' gestation or more) | Study population | RR 0.71 (0.08 to 6.63) | 156 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3,4 | ||

| 28 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (2 to 188) | |||||

| Maternal death (death while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy) | Study population | RR 0 (0 to 0) | 00 (0 study) | Not reported | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Side effects (any reported throughout intervention period) | Study population | RR 0.56 (0.37 to 0.84) | 1777 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1,5 | ||

| 330 per 1000 | 185 per 1000 (122 to 277) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 400 per 1000 | 224 per 1000 (148 to 336) | |||||

| Severe anaemia at any time during second and third trimester (Hb less than 70 g/L) | Study population | 1240 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1,6 | No events | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Maternal clinical malaria or other infection in pregnancy | Study population | RR 0 (0 to 0) | 00 (0 study) | Not reported | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Studies contributing data had serious design limitations

2Wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect

3Single study contributing data had design limitations

4Wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect and few events

5High heterogeneity I² > 80%

6No events

For assessments of the overall quality of evidence for each outcome that included pooled data from included trials, we downgraded the evidence from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias. This assessment was limited only to the trials included in this review and, as we did not consider there was a serious risk of indirectness or publication bias, we did not downgrade in these domains.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analysis on the primary outcomes based on the following criteria.

-

By gestational age at start of supplementation:

early (supplementation started before 20 weeks' gestation or prior to pregnancy);

late gestational age (supplementation started at 20 weeks of gestation or later);

unspecified gestational age or mixed gestational ages at the start of supplementation.

-

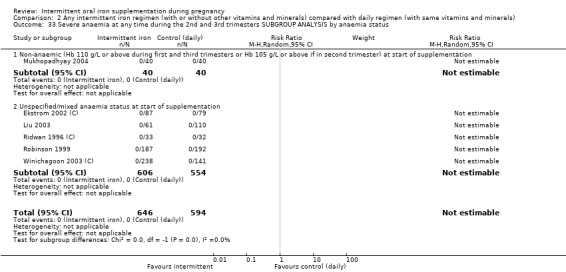

By anaemia status at baseline:

anaemic (Hb below 110 g/L during first and third trimesters or below 105 g/L in second trimester) at start of supplementation;

non‐anaemic (Hb 110 g/L or above during first and third trimesters or Hb 105 g/L or above if in second trimester) at start of supplementation;

unspecified/mixed anaemia status at start of supplementation.

-

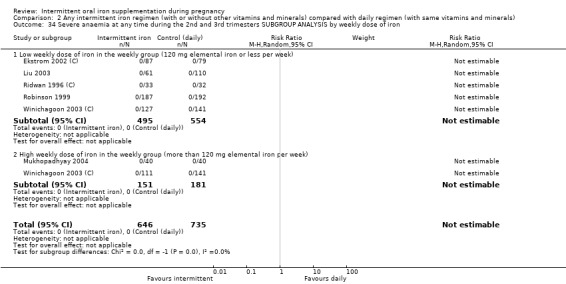

By weekly iron dose in the group receiving intermittent supplementation:

low weekly dose of iron in the intermittent group (120 mg elemental iron or less per week);

high weekly dose of iron in the intermittent group (more than 120 mg elemental iron per week).

-

By release speed of iron supplements:

slow release iron supplement (as indicated by trialists);

normal release iron supplement;

not specified/unreported/unknown.

-

By bioavailability of the iron compound relative to ferrous sulphate:

higher: NaFeEDTA (sodium iron ethylenediaminetetraacetate);

equivalent or lower: ferrous sulphate, ferrous fumarate, ferrous gluconate, other.

not specified/unreported/unknown.

-

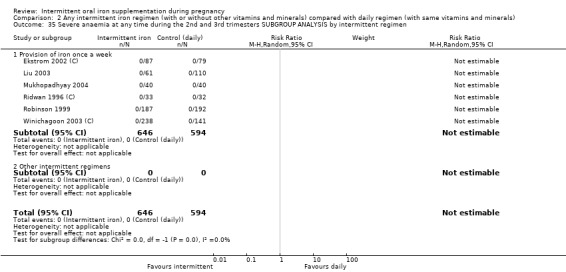

By intermittent iron supplementation regimen:

once a week;

other intermittent regimens.

-

By malaria endemicity of the area in which the trial was conducted:

malaria risk‐free area;

malaria risk area;

not specified/unreported/unknown.

We carried out formal subgroup analysis applying interaction texts as described in the Handbook (Higgins 2011) and have provided both subgroup and overall totals.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct a sensitivity analysis based on the quality of the studies. We considered a study to be of high quality if it was judged as having low risk of bias for both sequence generation and allocation concealment and in either blinding or loss to follow‐up. All of the trials contributing data to the review were considered at high or unclear risk of bias and none would have been retained in the analysis for sensitivity analysis. We will carry out planned sensitivity analysis by study quality if data from studies at low risk of bias are available for updates.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

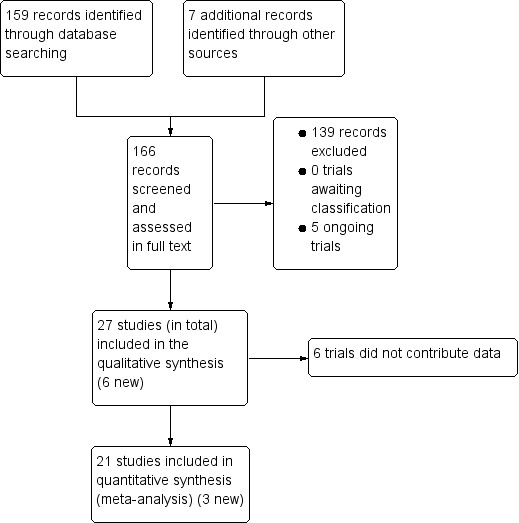

A single search was carried out for the last version of this review (Peña‐Rosas 2012) and a related review examining daily iron and iron plus folic acid supplementation in pregnancy (Peña‐Rosas 2015). An updated search was carried out looking for additional evidence. The study flow is depicted in Figure 1. We have included 27 trials (in total); six of them (Alaoddolehei 2013; Bouzari 2011; Goshtasebi 2012; Hashim 2012; Mumtaz 2000; Quintero 2004), which were otherwise eligible for inclusion, did not provide outcome data that we were able to use for the meta‐analysis. Of these, four studies comparing intermittent iron alone (Alaoddolehei 2013; Bouzari 2011; Hashim 2012; Quintero 2004), and two studies comparing intermittent iron + folic acid (Goshtasebi 2012; Mumtaz 2000), versus daily regimens were not included in the quantitative analysis. We excluded 139 studies. We identified five ongoing or unpublished trials (Agrawal 2012; Gies 2010; Goonewardene 2014; Kumar 2014; Sherbaf 2012). Details of all studies are provided in Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

1.

Study flow diagram for 2015 update

In addition to the published papers, abstracts and reports identified by the search, several trial authors provided additional, unpublished information for inclusion in the review (Casanueva 2006; Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Hanieh 2013 (C); Liu 2003; Pita Martin 1999; Quintero 2004; Ridwan 1996 (C); Robinson 1999; Yu 1998. For the (Winichagoon 2003 (C)) trial we have unpublished data only.

We have treated a trial in Guatemala, that included two sub studies, as two separate trials: one with supervised intake (Chew 2004b), and one with unsupervised intake (Chew 2004a). One trial in China (Liu 2003), involved three comparison groups: one receiving weekly doses of iron, one receiving daily doses of iron and a control group. Since the allocation of the control group was not randomised, we included this study in our comparisons of the effects of intermittent versus daily iron supplementation, but have not used the control group in any comparison. Similarly, a three‐arm trial by Pita Martin 1999 included a control group receiving no supplementation, but again participants in the control arm were not selected randomly, and we have not included data for this group in the review (Pita Martin 1999).

Included studies

Settings

The studies included in the review were carried out over the last two decades in countries across the globe: Argentina (Pita Martin 1999), Bangladesh (Ekstrom 2002 (C)), China (Liu 2003), Guatemala (Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a), India (Bhatla 2009; Grover 1998; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Singh 2011), Indonesia (Ridwan 1996 (C); Robinson 1999), Iran (Alaoddolehei 2013; Bouzari 2011; Goshtasebi 2012; Yekta 2011; Zamani 2008), Malawi (Young 2000), Malaysia (Hashim 2012), Mexico (Casanueva 2006; Quintero 2004; Viteri 2012), Pakistan (Mumtaz 2000; Rukhsana 2006), South Korea (Yu 1998), Sri Lanka (Goonewardene 2001),Thailand (Winichagoon 2003 (C)), and Vietnam (Hanieh 2013 (C)).

According to the WHO Global Malaria Report 2014 (WHO 2014d) and WHO international travel and health (WHO 2011d), all the included studies took place in countries with some malaria risks of diverse characteristics. All the study sites were located in countries that in 2014 had some malaria risk in parts of the country (Alaoddolehei 2013; Bouzari 2011; Casanueva 2006; Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a; Goshtasebi 2012; Hanieh 2013 (C); Hashim 2012; Liu 2003, Pita Martin 1999; Quintero 2004;Viteri 2012; Yekta 2011; Yu 1998; Zamani 2008), or in locations with malaria risk locations (Bhatla 2009; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Grover 1998; Goonewardene 2001; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Mumtaz 2000; Ridwan 1996 (C); Robinson 1999; Rukhsana 2006; Singh 2011; Winichagoon 2003 (C); Young 2000). Only one of the trials, carried out in Indonesia, specifically reported that it was conducted in a malaria‐endemic area (Robinson 1999).

In some of these countries/territories, malaria is present only in certain areas or up to a particular altitude. In many countries, malaria has a seasonal pattern (WHO 2014d; WHO 2011e). These details as well as information on the predominant malaria species, status of resistance to antimalarial drugs for each country where an included study was conducted were extracted for 2011 (WHO 2014d, (WHO 2011d; WHO 2011e) and provided in the notes section Characteristics of included studies section.

Participants

In all of the included studies, women known to have severe anaemia at recruitment were excluded, In the trials by Alaoddolehei 2013; Bhatla 2009; Bouzari 2011; Casanueva 2006; Goshtasebi 2012; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Singh 2011; Yekta 2011 and Zamani 2008, none of the women were anaemic; in the trial by Mumtaz 2000 women were anaemic at baseline while in the remaining trials, samples may have included some women with moderate or mild anaemia at baseline.

In nine of the studies, women were recruited and supplementation started before 20 weeks of gestation ( Bhatla 2009; Bouzari 2011; Goshtasebi 2012; Hanieh 2013 (C); Hashim 2012; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Winichagoon 2003 (C); Yekta 2011; Zamani 2008); in the remaining studies, gestational age at the start of supplementation was mixed or unclear.

Interventions

Intermittent regimens

Most of the intermittent regimens involved women taking supplements on one day each week (usually two tablets on the same day each week). Nine trials examined different types of intermittent regimens; in the trials by Goshtasebi 2012; Hanieh 2013 (C); Mumtaz 2000; Rukhsana 2006; Yekta 2011, one of the study arms received iron two times a week; in the trial by Grover 1998 women in the intermittent group took supplements on alternate days, and in that by Pita Martin 1999 and Alaoddolehei 2013 every three days. In the trials by Bouzari 2011 and Goonewardene 2001 one study arm received iron once weekly, another iron three times a week, and a third group received daily iron; and in the trial by Rukhsana 2006, one study arm received iron once weekly, another two times a week and a third group received daily iron.

Weekly dose of iron in the arm receiving intermittent supplements

The weekly dose of iron ranged between 80 mg elemental iron per week and 300 mg of iron. In one trial, the weekly dose was 80 mg elemental iron per week (Mumtaz 2000), while another provided 90 mg elemental iron per week (Zamani 2008). Five studies provided 100 mg elemental iron weekly in the intermittent regimen (Goonewardene 2001; Goshtasebi 2012;Grover 1998; Singh 2011; Yekta 2011); in 12 trials women received 120 mg elemental iron per week (Casanueva 2006; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Hanieh 2013 (C); Hashim 2012; Liu 2003; Pita Martin 1999; Ridwan 1996 (C); Robinson 1999; Rukhsana 2006; Quintero 2004; Viteri 2012; Young 2000); in one study the weekly iron dose was 160 mg elemental iron (Yu 1998); in two trials women received in total a weekly dose of 180 mg elemental iron (Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a); three trials provided 200 mg elemental iron (Bhatla 2009; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Singh 2011). Two studies tested two different intermittent doses of iron, once a week: 100 and 150 mg elemental iron per week in the study by Bouzari 2011, and 120 and 180 mg elemental iron per week in the study by Winichagoon 2003 (C).

The dose of iron in the daily supplementation comparison groups ranged from 40 mg elemental iron daily (Mumtaz 2000); 45 mg elemental iron daily (Zamani 2008); 50 mg elemental iron daily (Alaoddolehei 2013; Bouzari 2011; Goshtasebi 2012; Yekta 2011); 60 mg elemental iron daily (Casanueva 2006; Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Hanieh 2013 (C); Hashim 2012; Liu 2003; Pita Martin 1999; Ridwan 1996 (C); Rukhsana 2006; Robinson 1999; Viteri 2012; Winichagoon 2003 (C); Young 2000); 80 mg elemental iron daily (Yu 1998); 100 mg elemental iron daily (Bhatla 2009; Goonewardene 2001; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Quintero 2004; Singh 2011) to 120 mg elemental iron daily (Liu 2003).

Weekly dose of folic acid in the arm receiving intermittent supplements

For trials providing also folic acid intermittently as part of the intervention, the doses were: 400 μg (0.4 mg) folic acid per week (Casanueva 2006; Viteri 2012); 500 μg (0.5 mg) folic acid (Ekstrom 2002 (C); Liu 2003; Young 2000); 1000 μg (1 mg) folic acid per week (Alaoddolehei 2013; Bhatla 2009; Goshtasebi 2012; Mukhopadhyay 2004); 1500 μg (1.5 mg) folic acid a week (Grover 1998; Singh 2011); 2000 μg (2.0 mg) folic acid per week (Mumtaz 2000); 3000 μg (3 mg) folic acid per week (Hanieh 2013 (C)); and 3500 μg (3.5 mg) folic acid per week (Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a; Winichagoon 2003 (C)).

Type of iron compounds

All supplements used in trials were equivalent or lower, rather than high relative bioavailability iron compounds (ferrous sulphate and ferrous fumarate) and appeared to be standard, rather than slow‐release, preparations. Bioavailability of iron compounds is assessed in comparison (relative) to ferrous sulphate.

Laboratory method for ferritin concentration

Three laboratory methods were reported by the trials: enzyme‐linked‐immuno‐absorben‐assay (ELISA) (Casanueva 2006; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Mumtaz 2000; Pita Martin 1999; Ridwan 1996 (C); Alaoddolehei 2013; Singh 2011; Viteri 2012; Winichagoon 2003 (C)); radioimmunoassay (RIA) (Ekstrom 2002 (C); Goonewardene 2001; Goshtasebi 2012; Yekta 2011); and chemiluminescence‐immunoassay (CLIA) (Hanieh 2013 (C)). In the remaining trials, the ferritin was not measured or the laboratory method was not reported.

Supervision and co‐interventions

In most of the studies women took the supplements without supervision; in the Chew 2004b study women in both the intermittent and daily supplementation groups took supplements under supervision; in the Robinson 1999 trial women in the daily supplementation group were unsupervised, whereas the weekly group was supervised. Some studies included co‐interventions in addition to the nutritional supplement. For example, in the study by Bhatla 2009 the intervention included health education on diet and nutrition. Women in one study (Singh 2011), received deworming treatment at the start of the study. In most studies women received advice on when to take supplements (e.g. before meals).

Setting and health worker cadre

Most (98%) of the trials reported the type of healthcare facility where the trial was conducted, most frequently this was an antenatal clinic. Although the information about the health worker cadre that delivered the intervention was less explicit, in most of the cases it could be reasonably deduced from other details in the report. In three studies iron supplements were supplied by lay workers (Ekstrom 2002 (C); Hanieh 2013 (C); Mukhopadhyay 2004; Winichagoon 2003 (C)), in two trials by midwives (Ridwan 1996 (C);Young 2000), in one by traditional birth attendants (Robinson 1999), and in the rest of the cases by physicians, obstetricians or haematologists.

Comparisons

1. Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with no supplementation or placebo

No studies contributed data.

2. Any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) compared with any daily iron regimen (with same vitamins and minerals)

Twenty‐one studies contributed data and compared any intermittent iron regimen (with or without other vitamins and minerals) versus any daily regimen (with the same vitamins and minerals) (Bhatla 2009; Casanueva 2006; Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Goonewardene 2001; Grover 1998; Hanieh 2013 (C); Liu 2003; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Pita Martin 1999; Ridwan 1996 (C); Robinson 1999; Rukhsana 2006; Singh 2011; Viteri 2012; Winichagoon 2003 (C); Yekta 2011; Young 2000; Yu 1998; Zamani 2008).

3. Intermittent oral iron alone supplementation compared with no supplementation or placebo

One study examining the provision of intermittent iron alone included a control group receiving no supplementation (Pita Martin 1999). However, as the control group was not selected randomly we have not included these data in this comparison. No other studies compared intermittent iron alone with no supplementation or placebo.

4. Intermittent oral iron + folic acid supplementation compared with no supplementation or placebo, and, 5. Intermittent oral iron + vitamins and minerals supplementation compared with no supplementation or placebo

No studies compared intermittent iron + folic acid with or without other vitamins and minerals with the effects of no supplementation or placebo.

6. Intermittent oral iron alone supplementation compared with daily oral iron alone supplementation

Three studies contributed data to this comparison (Pita Martin 1999; Yekta 2011; Yu 1998).

7. Intermittent oral iron + folic acid supplementation compared with daily oral iron + folic acid supplementation

Fourteen trials reporting on the outcomes included in the review compared the effects of intermittent iron + folic acid supplementation with the effects of daily iron + folic acid supplementation (Bhatla 2009; Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Grover 1998; Hanieh 2013 (C); Liu 2003; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Ridwan 1996 (C); Robinson 1999; Rukhsana 2006; Winichagoon 2003 (C); Young 2000; Zamani 2008).

8. Intermittent oral iron + vitamins and minerals supplementation compared with daily oral iron + vitamins and minerals supplementation

Four studies contributed data to this comparison. Three (Casanueva 2006; Singh 2011; Viteri 2012) compared intermittent supplementation with iron + folic acid + vitamin B12 with the effects of daily supplementation with iron + folic acid + vitamin B12, while another study (Goonewardene 2001) compared the effects of daily, once weekly and three times weekly supplementation with a dose of iron + folic acid + vitamin B12, vitamin B6, vitamin B1, niacinamide and vitamin C.

See the table of Characteristics of included studies for a detailed description of the studies, including iron doses used. All included studies met the pre‐stated inclusion criteria.

Excluded studies

We excluded 139 studies. The main reason for excluding trials was that they did not compare intermittent versus daily regimens or no supplementation/placebo. Trials comparing daily iron supplementation (with or without folic acid and, or other vitamins and minerals) with placebo or no supplementation are included in a related review (Peña‐Rosas 2015). Descriptions of excluded studies along with the reasons for exclusion are set out in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

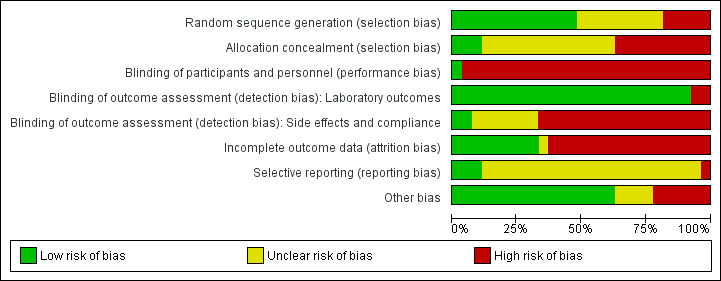

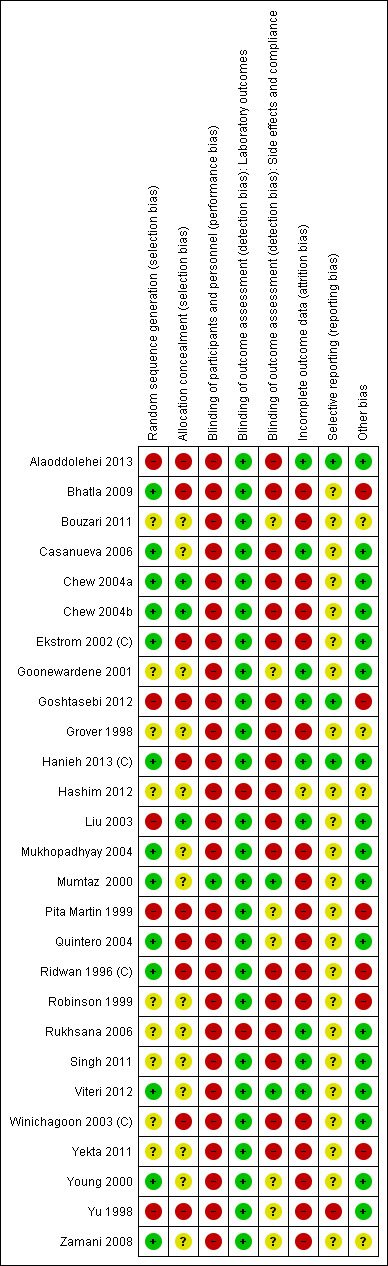

Risk of bias in included studies

For the cluster‐randomised trials we have used the same domains to assess risk of bias as those used where there was individual‐randomisation, however, we have noted in the 'Risk of bias' tables where there are additional possible sources of bias associated with cluster design (e.g. whether the data were adjusted to take account of cluster design effect).

Allocation

Sequence generation

Most of the included trials used computer‐generated random number sequences or random number tables to randomly allocate the intervention groups (Bhatla 2009; Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Hanieh 2013 (C); Mukhopadhyay 2004; Mumtaz 2000; Quintero 2004; Ridwan 1996 (C); Viteri 2012; Young 2000; Zamani 2008). Casanueva 2006 used a method involving drawing lots with a 50% probability of participants being allocated to intervention or control groups. Ten trials did not report, or did not state clearly, the randomisation method used (Bouzari 2011; Goonewardene 2001; Grover 1998; Hashim 2012; Liu 2003; Robinson 1999; Rukhsana 2006; Singh 2011; Winichagoon 2003 (C); Yekta 2011), although in Liu 2003 the non‐supplemented group was self‐selected and so we have assessed this as being at high risk. Four trials were quasi‐randomised using alternation or other non random sequences (Alaoddolehei 2013; Goshtasebi 2012; Pita Martin 1999; Yu 1998).

Allocation concealment

Three trials reported using sealed envelopes when allocating women to treatment groups (Chew 1996a; Chew 1996b; Liu 1996). In the study by Zamani 2008, it was reported that coded vials were used; it was not clear whether the person allocating women to treatment groups also distributed the supplements. If so, then group allocation could possibly be anticipated, as while women in both groups received a supply for a month, one group received eight tablets and the other 30; the vials were likely to have felt different to experienced staff. In 13 other trials there was no description of the methods used to conceal allocation or the description was brief or unclear (Bouzari 2011; Casanueva 2003a; Goonewardene 2001; Grover 1998; Hashim 2012; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Mumtaz 2000; Robinson 1998; Rukhsana 2006; Singh 2011; Viteri 2010; Yekta 2011; Young 2000). In the study by Hanieh 2013 (C), the supplements were in blister packs with codes A, B and C. However, the study was open for the daily supplementation group. Nine other trials were assessed as being at high risk of bias for this domain as they used quasi‐randomisation methods including alternate allocation or allocation by day of the week, so that those carrying out randomisation would be aware of allocation at the point of randomisation (Alaoddolehei 2013; Alizadeh 2010; Bhatla 2009; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Pita Martin 1999; Quintero 2004; Ridwan 1996 (C); Winichagoon 2003 (C); Yu 1998).

Blinding

Blinding of participants, staff and outcome assessors

Clearly, trialists comparing the effects of intermittent supplementation regimens with the effects of daily supplementation regimens would have had difficulty keeping participants blinded as to what treatment they were receiving as this would have required that participants on an intermittent regimen receive placebo for some days. The study conducted by Mumtaz 2000 was the only one that provided placebos during the days that women did not consume the iron supplements. In the rest of the included studies there was no attempt to blind participants by providing inactive supplements to women in the intermittent arms of trials. Similarly, staff providing care were unlikely to have been blinded to group allocation. In several studies it was stated that outcome assessment (at least for laboratory measurements) was carried out by technicians blinded to the study arms (Bhatla 2009; Hanieh 2013 (C); Liu 2003; Mukhopadhyay 2004; Pita Martin 1999; Robinson 1999; Viteri 2012; Yu 1998; Zamani 2008). At the same time, we considered that lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect laboratory outcomes as these are usually done elsewhere. This would be the case for all but two of the remaining studies (Alaoddolehei 2013; Bouzari 2011; Casanueva 2006; Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Goonewardene 2001; Goshtasebi 2012; Grover 1998; Mumtaz 2000; Quintero 2004; Ridwan 1996 (C); Singh 2011; Winichagoon 2003 (C); Yekta 2011; Young 2000). Two studies were assessed as high risk as they did not even mention the laboratory analysis (Hashim 2012; Rukhsana 2006).

While lack of blinding may not represent a serious source of bias for some outcomes (e.g. serum indicators of anaemia) other outcomes (reporting of side effects) may have been affected by knowledge of treatment group.

Incomplete outcome data

Loss of participants to follow‐up, missing data and lack of intention‐to‐treat analyses were serious problems with almost all of the included studies. Avoiding sample attrition in this type of study would not be simple; women who became anaemic were withdrawn from some trials so that they could receive treatment; and withdrawals for this reason may not have been balanced across study arms. In some studies women withdrew because they experienced side effects and there was no intention‐to‐treat analyses. High levels of sample attrition mean that studies are at serious risk of bias, and that results are more difficult to interpret.

In all studies, women were followed up over several months and so we anticipated some attrition and set a cut‐off of 20% as being a reasonable level of loss to follow‐up. In nine studies the attrition was less than 20% or nil and any loss was balanced across groups (Alaoddolehei 2013; Casanueva 2006; Goonewardene 2001; Goshtasebi 2012; Hanieh 2013 (C); Liu 2003; Rukhsana 2006; Singh 2011; Viteri 2012); these studies were assessed as being at low risk of attrition bias. In three studies (Bhatla 2009;Bouzari 2011; Yekta 2011) loss was not balanced across groups and post‐randomisation exclusions may have related to the interventions; for example, if women were unable to tolerate the iron supplements they were excluded. One study did not provide information about sample attrition (Hashim 2012). In all other studies attrition exceeded 20% (Chew 2004b; Chew 2004a; Ekstrom 2002 (C); Mukhopadhyay 2004; Mumtaz 2000; Quintero 2004; Ridwan 1996 (C); Robinson 1999; Winichagoon 2003 (C); Zamani 2008). In five studies a third or more of the women randomised were lost to follow‐up: in the study by Ekstrom 2002 (C) a third of the sample was not followed up, and losses were even greater in the trials by Grover 1998 (40%), Young 2000 (47%), Yu 1998 (47%) and Pita Martin 1999 (57%).

Selective reporting

We had access to trial registrations or protocols for three studies and these studies were assessed as being at low risk of outcome reporting bias (Alaoddolehei 2013; Goshtasebi 2012; Hanieh 2013 (C)). One study reported outcomes only for those women where compliance was known to be high and this study was therefore assessed as being at high risk of bias for this domain (Yu 1998). In the study by Zamani 2008, it was stated that data were collected on outcomes at delivery, which were not reported in the results. However, it is possible these data will be published in future papers. For the remaining studies we did not have access to study protocols and therefore, formally assessing reporting bias was not possible (all assessed as unclear). Insufficient studies contributed data to allow us to carry out exploration of possible publication bias.

Other potential sources of bias

In three studies there was some evidence of baseline imbalance between groups: in the Ridwan 1996 (C) and Yekta 2011 trials women in the weekly supplementation group had lower Hb levels at baseline, and in the Bhatla 2009 trial the daily group started supplements at earlier gestational ages. In the study by (Goshtasebi 2012), the authors reported that due to financial constraints the trial was open and baseline ferritin values were not evaluated for comparability among the groups; and the supervision of adherence was not done. In the trials by Pita Martin 1999 and Robinson 1999, there were changes in protocol during the trial. All of these studies were assessed as high risk of other bias.

In one study (Grover 1998), background data were only provided for those women completing the study, so it was not clear whether women who remained at follow‐up had the same characteristics as those that dropped out or were excluded. In other studies it was not clear from the methods whether studies were likely to be at risk of other sources of bias (Bouzari 2011; Hashim 2012; Zamani 2008).

The remaining studies were all assessed as low risk of bias for this domain. Groups appeared balanced at baseline and other sources of bias were not apparent.

Cluster‐randomised trials

Four trials used cluster‐randomisation (Ekstrom 2002 (C); Hanieh 2013 (C); Ridwan 1996 (C); Winichagoon 2003 (C)). In the trials by Ridwan 1996 (C); Hanieh 2013 (C) and Winichagoon 2003 (C), we were able to adjust the sample sizes to take account of the cluster design effect using data provided by the trial authors. Cluster design effect was estimated but not taken into account in the analysis of Ekstrom 2002 (C).

None of the studies included in this review were rated as high quality. Full details of 'Risk of bias' assessments are included in Characteristics of included studies tables. We have also included figures which summarise our 'Risk of bias' assessments (Figure 2; Figure 3), which we used to help us judge study quality in the Summary of Findings tables (seeTable 1; Table 2).

2.