Abstract

Background

Testing for carcino‐embryonic antigen (CEA) in the blood is a recommended part of follow‐up to detect recurrence of colorectal cancer following primary curative treatment. There is substantial clinical variation in the cut‐off level applied to trigger further investigation.

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic performance of different blood CEA levels in identifying people with colorectal cancer recurrence in order to inform clinical practice.

Search methods

We conducted all searches to January 29 2014. We applied no language limits to the searches, and translated non‐English manuscripts. We searched for relevant reviews in the MEDLINE, EMBASE, MEDION and DARE databases. We searched for primary studies (including conference abstracts) in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Science Citation Index & Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science. We identified ongoing studies by searching WHO ICTRP and the ASCO meeting library.

Selection criteria

We included cross‐sectional diagnostic test accuracy studies, cohort studies, and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of post‐resection colorectal cancer follow‐up that compared CEA to a reference standard. We included studies only if we could extract 2 x 2 accuracy data. We excluded case‐control studies, as the ratio of cases to controls is determined by the study design, making the data unsuitable for assessing test accuracy.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (BDN, IP) assessed the quality of all articles independently, discussing any disagreements. Where we could not reach consensus, a third author (BS) acted as moderator. We assessed methodological quality against QUADAS‐2 criteria. We extracted binary diagnostic accuracy data from all included studies as 2 x 2 tables. We conducted a bivariate meta‐analysis. We used the xtmelogit command in Stata to produce the pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity and we also produced hierarchical summary ROC plots.

Main results

In the 52 included studies, sensitivity ranged from 41% to 97% and specificity from 52% to 100%. In the seven studies reporting the impact of applying a threshold of 2.5 µg/L, pooled sensitivity was 82% (95% confidence interval (CI) 78% to 86%) and pooled specificity 80% (95% CI 59% to 92%). In the 23 studies reporting the impact of applying a threshold of 5 µg/L, pooled sensitivity was 71% (95% CI 64% to 76%) and pooled specificity 88% (95% CI 84% to 92%). In the seven studies reporting the impact of applying a threshold of 10 µg/L, pooled sensitivity was 68% (95% CI 53% to 79%) and pooled specificity 97% (95% CI 90% to 99%).

Authors' conclusions

CEA is insufficiently sensitive to be used alone, even with a low threshold. It is therefore essential to augment CEA monitoring with another diagnostic modality in order to avoid missed cases. Trying to improve sensitivity by adopting a low threshold is a poor strategy because of the high numbers of false alarms generated. We therefore recommend monitoring for colorectal cancer recurrence with more than one diagnostic modality but applying the highest CEA cut‐off assessed (10 µg/L).

Plain language summary

Detecting recurrent colorectal cancer by testing for blood carcino‐embryonic antigen (CEA).

Background

After surgery for cancer in the colon or rectum (colorectal cancer), most people are intensively followed up for at least five years to monitor for signs of the cancer returning. When this occurs, it usually causes a rise in a blood protein called CEA (carcino‐embryonic antigen). An increased level of CEA can be picked up by a blood test, which is normally done every three to six months after colorectal cancer surgery. Those people with raised CEA levels are further investigated by x‐ray imaging (usually a scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis). We conducted this review to help decide what level of blood CEA should lead to further investigation.

Key Results

This review shows that setting a low cut‐off point will increase the number of genuine cases of colorectal cancer recurrence that are detected (true positives), but a low cut‐off will also cause unnecessary alarm by incorrectly classifying too many cases that are not actually recurrences (false positives). In addition, this review shows that a rise in CEA does not occur in up to 20% of patients with a true recurrence (false negatives). The current evidence supports using the highest cut‐off point assessed (10 µg/L), but that adding another diagnostic modality (e.g. a single scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis at 12 to 18 months) is necessary in order to avoid the missed cases.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of results table: different cut‐offs.

| Review question: What is the accuracy of single‐measurement blood CEA as a triage test to prompt further investigation for colorectal cancer recurrence after curative resection? | ||||

| Population: adults with no detectable residual disease after curative surgery (with or without adjuvant therapy) | ||||

| Studies: cross‐sectional diagnostic test accuracy studies, cohort studies, and RCTs, reporting 2 x 2 data | ||||

| Index test: Blood carcino‐embryonic antigen (CEA) | ||||

| Reference standard: appropriate¹ imaging, histology, or routine clinical follow‐up | ||||

| Setting: primary or hospital care. | ||||

| Subgroup | Number (Studies) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

Interpretation Assuming a constant incidence of 2%² recurrence at each measurement point, testing 1000 people will have the following outcome depending on the CEA threshold applied |

| 2.5 µg/L | 1515 (7) | 82% (78 to 86) | 80% (59 to 92) | 16 cases of recurrence will be detected and 4 cases will be missed. 196 people will be referred unnecessarily for further testing |

| 5 µg/L | 4585 (23) | 71% (64 to 76) | 88% (84 to 92) | 14 cases of recurrence will be detected and 6 cases will be missed. 118 people will be referred unnecessarily for further testing |

| 10 µg/L | 2341 (7) | 68% (53 to 79) | 97% (90 to 99) | 14 cases of recurrence will be detected and 6 cases will be missed. 29 people will be referred unnecessarily for further testing |

1as defined in the Reference standards section of the Methods. 2three‐monthly prevalence is estimated as 2%, as the median prevalence amongst the included studies was 30% and a standard follow‐up schedule will include 14 to 15 CEA tests over five years.

Background

International guidelines recommend that blood carcino‐embryonic antigen (CEA) levels are measured to detect recurrent colorectal cancer (CRC) as part of an intensive follow‐up regimen (Duffy 2013b; Labianca 2010; Locker 2006; NCCN 2013; NICE 2011).

A previous Cochrane review (Jeffery 2007) of eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Kjeldsen 1997; Makela 1995; Ohlsson 1995; Pietra 1998; Rodriguez‐Moranta 2006b; Schoemaker 1998; Secco 2002; Wattchow 2006) evaluated the impact of follow‐up strategy on overall survival and the number of recurrences detected. The analysis included very scant data on CEA; data on overall survival were only available from one trial (odds ratio (OR) 0.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.26 to 1.29) and data on recurrence rate only from two (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.25).The follow‐up strategies implemented in each study were instead broadly classed as either intensive or minimal and the investigative modalities included in each strategy varied greatly between studies. Compared to minimal follow‐up, it was estimated that an intensive regimen could significantly reduce five‐year all‐cause mortality (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.91).

The validity of this conclusion has been questioned because the mechanism by which a mortality reduction of this magnitude could be achieved by treating asymptomatic recurrence is unclear. There is evidence from one trial that starting chemotherapy for recurrence at an asymptomatic rather than symptomatic stage increases length of survival by a median of five months (Glimelius 1992). There is also observational evidence that surgical resection of metastases when feasible is associated with over 40% survival at five years (Colibaseanu 2013; Gonzalez 2013; Kanas 2012), and one commentator has suggested that advances in chemotherapy, hepatic resection, and multidisciplinary CRC follow‐up mean that the clinical benefits of intensive follow‐up will be even greater today (Labianca 2010). It is certainly true that there are now a number of well‐tolerated effective chemotherapy regimens for recurrent CRC in older populations (Cunningham 2010; Locker 2006). However, the authors of the CEASL (CEA second‐look) trial argue that identifying and treating asymptomatic recurrence has the potential to increase overall mortality (Treasure 2014), and the FACS (Follow‐up After Colorectal Surgery) trial suggests that the effect of follow‐up on absolute mortality is much smaller than that suggested by the 2007 review (Primrose 2014).

Nevertheless, the FACS trial has re‐awakened interest in CEA follow‐up. It showed that measuring blood CEA three‐ to six‐monthly for five years, augmented by a single CT (computed tomography) scan at 12 to 18 months, leads to earlier diagnosis of recurrence and increases by about three‐fold the proportion of recurrences that can be treated with curative intent (Primrose 2014). As CEA monitoring does not involve x‐rays, it can be done in the community, and is potentially more cost‐effective than CT imaging. The FACS trial result has raised substantial interest in CEA as a first‐line follow‐up modality.

CEA is a glycoprotein involved in cell adhesion produced during foetal development. Production usually ceases at birth, but elevated levels can be detected in people with colorectal, breast, lung and pancreatic cancer, in smokers, and in people with benign conditions such as cirrhosis of the liver, jaundice, diabetes, pancreatitis, chronic renal failure, colitis, diverticulitis, irritable bowel syndrome, pleurisy and pneumonia (Newton 2011; Sturgeon 2009). Prior to first diagnosis, CEA levels may rise between four and eight months before the development of cancer‐related symptoms (Goldstein 2005). Approximately 90% of colorectal cancers produce CEA (Dallas 2012). Predicting those people who do not secrete CEA is a challenge, with conflicting reports regarding whether well‐ or poorly‐differentiated tumours are associated with increased secretion (Davidson 1989). During follow‐up, CEA appears to be most sensitive for detecting hepatic and retroperitoneal metastases, and is least sensitive for local recurrences and peritoneal or pulmonary disease (Scheer 2009; Tsikitis 2009). However, CEA needs to be seen as a triage test (where a rise should lead to further investigation rather than initiation of therapy), as it gives no information about the location and extent of recurrence (Duffy 2013b).

Although serial CEA measurements are taken during follow‐up, the decision to investigate further with imaging is usually based on a single elevated CEA measurement (although a repeat blood test is often done to confirm the raised level). An absolute threshold somewhere between 3 and 7 µg/L is typically used to trigger further investigation. In the FACS trial, the threshold used was based on the difference of the CEA level at a single time point from the postoperative baseline (Primrose 2014).

The most recent systematic review exploring the accuracy of CEA for diagnosing recurrent CRC includes a meta‐analysis of 20 studies (Tan 2009). These studies implemented a wide range of thresholds (3 to 15 µg/L) and measured CEA using a variety of test kits. The pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity were 64% (95% CI 61% to 67%) and 90% (95% CI 89% to 91%) respectively. The pooled area under the curve (AUC) was 0.79 (standard error = 0.054). A subgroup analysis of four studies that reported accuracy at a threshold of 3 µg/L gave an improved sensitivity of 73% (95% CI 69% to 77%) but at the expense of a reduced specificity of 68% (95% CI 65% to 72%). Based on a metaregression analysis, the authors suggest that a cut‐off of 2.2 µg/L provides the ideal balance between sensitivity and specificity, but this is based on extrapolation beyond the data analysed, as the lowest threshold applied in any included study was 3 µg/L. We were also unable to identify some of the data included in the analysis from the published studies.

Target condition being diagnosed

Colorectal cancer is globally the third most common cancer, accounting for 9.8% of all detected cancers. In 2008, the age‐standardised incidence rate was 17.3 cases per 100,000 (30.1 in high‐income countries and 10.7 in low‐ or middle‐income countries) (Ferlay 2013).

Colorectal adenocarcinoma arises in the colonic mucosa and progressively invades through the layers of bowel wall into surrounding structures, leading to peritoneal, neural, lymphatic and haematological metastasis (Gore 1997). This process provides the basis of the internationally recognised TNM (tumour node metastasis) staging system (Sobin 2009) and the earlier Dukes classification (Dukes 1932). The first site of haematological metastasis is the liver via the portal vein, after which distant metastasis occurs most commonly in the lungs but also in the bones and brain (Guthrie 2002). Prognosis is closely related to stage, with higher‐grade metastatic tumours having a poorer prognosis (Maringe 2013). Approximately two‐thirds of patients will present with a primary CRC amenable to radical surgery (Jeffery 2007).

Following surgery, however, 30% to 50% of patients will develop recurrence (Labianca 2010), although the results of the FACS trials suggest that perhaps half these cases result from inadequate preliminary staging and might have been detectable through more rigorous investigation at the time of primary treatment (Primrose 2014). The most common site for recurrence is the liver, followed by the lungs, but it can also occur in the abdomen and pelvis (Cunningham 2010; Jeffery 2007).

As stated in the Background, the effectiveness of treatment of recurrence is a matter of hot debate (Godlee 2014; Treasure 2014). In the absence of trials of treatment versus no treatment, most estimates of impact are based on observational data. Patients undergoing secondary surgery with curative intent have a median survival time of 35.8 to 84.8 months. Chemotherapy has been estimated to prolong life by one to two years (Arriola 2006; Cunningham 2010; Tsikitis 2009). However, apart from the Nordic trial showing that the initiation of chemotherapy at an asymptomatic stage increases survival (Glimelius 1992), there is no evidence from trials to confirm that treatment of early‐diagnosed asymptomatic recurrence improves survival or other outcomes. There is a need therefore to determine the most accurate means of detecting early‐stage recurrence before the impact of treatment strategies can be further explored.

Index test(s)

CEA is a relatively simple and low‐cost biomarker that can be detected by a blood test. The analysis of CEA in clinical studies utilises the technique of immunoassay in a variety of forms and from a number of different manufacturers. Earlier methods were manual immunoassays, such as radio‐immunoassay, but most laboratories now use fully automated non‐isotopic methods. The reproducibility of these fully automated methods are generally superior to the older manual methods. Unfortunately, the details of the methods used in clinical studies and their analytical performance are often lacking (Wild 2013).

Data from external quality assessment schemes have repeatedly shown good precision for most methods at low CEA concentrations. In 2010, within‐laboratory precision over a 12‐month period at a concentration of 3 µg/L (equivalent to 54 U/L) was less than 9% on average for all major methods. A greater analytical challenge is the difference in method bias (Wild 2013). Despite the availability of an international reference preparation (IRP 73/601) since 1975 and its widespread use in commercial assays since the early 1990s, method bias may still be ± 20%, and the degree of this bias is often sample‐dependent (Bormer 1991; Laurence 1975). CEA has a complex molecular structure and the antibodies used in the immunoassays recognise different epitopes of the molecule, which is considered to be a major source of method bias (Bormer 1991). Consequently, the interpretation of data from clinical studies, especially the use of any particular threshold, needs to take account of the actual method used. Due to the good reproducibility but significant method‐dependent bias, it is advised that the same assay technique should be used throughout any follow‐up period (Duffy 2013b).

Clinical pathway

Following radical surgery (with or without adjuvant therapy), there is wide variation in the recommended intensive follow‐up regimen (Duffy 2013b; Labianca 2010; Locker 2006; NCCN 2013; NICE 2011).

The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend history, physical examination, and CEA determination every three to six months for the first three years, and every six to 12 months in years four and five. A colonoscopy is recommended at one year, then every three to five years looking for metachronous adenomas and cancers. A CT scan of the chest and contrast‐enhanced ultrasound scan (USS) or CT scan of the abdomen is recommended every six to 12 months for the first three years in patients considered to be at higher risk. Other laboratory and radiological examinations are not recommended unless patients have suspicious symptoms (Labianca 2010).

The American Society of Clincal Oncology (ASCO) recommends that CEA is performed every three months for the first three years in patients with stage II or III disease if the patient is a candidate for surgery or systemic therapy, and that raised CEA levels (> 5 µg/L, confirmed by a repeat test) warrant further evaluation for metastatic disease (Locker 2006). Unlike ASCO, ESMO does not specify a threshold nor limit testing to specific tumour stages. The European Group on Tumour Markers (EGTM) specify CEA measurement at baseline and then every two to three months for three years, then six‐monthly for five years in patients with stage II to III disease who would tolerate further surgery or systemic therapy. EGTM recommend that any increase in CEA (confirmed by a repeat test) should trigger further investigations (Duffy 2013b).

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommended follow‐up from four to six weeks following curative treatment, for all patients who could tolerate and accept the balance of risk and benefits of further treatment, including CEA measurement at least every six months in the first three years, two CT scans of the chest and abdomen in the first three years, and colonoscopy at one year and five years (NICE 2011).

Once recurrence is suspected on the basis of a raised CEA level, patients then undergo further diagnostic testing to confirm recurrence (Duffy 2013a). The modality used to provide a definitive diagnosis is usually either CT or USS, but could also be clinical assessment, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy and barium enema, CT colonography, positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET‐CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Prior test(s)

As detailed above, CEA is often the most frequently undertaken modality within an intensive follow‐up regimen. Prior testing in this context is irrelevant, because CEA is measured routinely within intensive follow‐up programmes.

Role of index test(s)

As a triage test to prompt further investigation for CRC recurrence.

Alternative test(s)

Circulating tumour cells and cytokeratins have been examined as possible biomarkers of CRC recurrence, but the studies are few and limited. Ca125 is regarded as an emerging biomarker for use in postoperative follow‐up, but as yet evidence is limited (Duffy 2013b; Newton 2011). CT imaging is the only other test that meta‐analysis suggests has potential to detect metastatic recurrence amenable to resection, but it is more expensive than measuring blood CEA. CT‐PET is used in some centres, but will only be preferred to standard CT for routine follow‐up if future evidence suggests much superior performance. Endoscopic imaging (colonoscopy) is routinely used as an adjunct to CEA or CT imaging or both in follow‐up care to detect metachronous polyps or cancer (and rarely intraluminal recurrence). Clinical and ultrasound examination lack sensitivity. MRI can realistically be applied only to the liver and lacks strong evidence of effectiveness in detecting recurrence.

Rationale

This diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) review aims to clarify the accuracy of blood CEA as a triage test for CRC recurrence. If found to be sufficiently accurate, CEA could be a cost‐effective means of reducing unnecessary, more expensive investigations.

Objectives

To determine the diagnostic performance of different blood CEA levels in identifying people with colorectal cancer recurrence in order to inform clinical practice.

Secondary objectives

To identify sources of between‐ and within‐study heterogeneity to inform future study designs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We include cross‐sectional diagnostic test accuracy studies, cohort studies, and RCTs that directly compared follow‐up after CRC resection using CEA to a reference standard. We included studies only if we could extract 2 x 2 accuracy data. We excluded case‐control studies, as the ratio of cases to controls is determined by the study design, making the data unsuitable for assessing test accuracy.

Participants

Participants were adults with no detectable residual disease after primary treatment with surgical resection (with or without adjuvant therapy) being followed‐up for recurrence.

Index tests

Blood carcino‐embryonic antigen (CEA).

Target conditions

Recurrence of colorectal cancer following curative resection, including locoregional recurrence and metastatic disease.

Reference standards

Imaging done per protocol or to investigate for suspected recurrence (usually CT, MRI or PET‐CT, but also endoscopy, CT colonography, ultrasound, and barium enema).

The histological confirmation of recurrence following surgery or tissue biopsy.

Routine clinical follow‐up used as a reference standard to confirm negative index test values where imaging is not indicated as part of the follow‐up schedule (standard protocols run for three to five years).

We had hoped to compare the results of using these different reference standards in a sensitivity analysis. However, the majority of studies (73%) reported a composite reference standard, including more than one of the three reference standards listed above, as part of a prespecified clinical pathway and so the specific reference standard applied varied between participants within the same study. Without individual patient data, identifying the exact investigative modality applied as the reference standard was not possible and so we did not conduct the planned sensitivity analysis.

We classified the chosen reference standard (or composite reference standard) used in each study as 'appropriate' (1 to 3 above), 'inappropriate' (a reference standard not included in 1 to 3 above), or 'not stated' for further subgroup analysis.

There were insufficient data available to classify deaths during follow‐up as 'death from CRC', 'death with CRC', 'death from other causes', or 'death unspecified', as detailed in the original protocol.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Our information specialist (NR, trained in Cochrane DTA methodology) designed our search strategy, and conducted all searches to January 29 2014. We applied no language limits to the searches, and translated non‐English manuscripts to assess suitability for inclusion.

We searched for relevant reviews in the MEDION database (www.mediondatabase.nl), using the search terms 'cea' OR 'carcinoembryonic' or 'carcino‐embryonic' and restricting to Malignancy OR Digestive. Using the same terms, we also searched MEDLINE (OvidsSP) [1946 to current, In‐process], and EMBASE (OvidSP) [1974 to current] using the Reviews Clinical Query, and the DARE database (the Cochrane Library, Wiley).

We searched for primary studies (including conference abstracts) in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cochrane Library, Wiley (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (OvidSP) [1946 to current, In‐process] (Appendix 2), EMBASE (OvidSP) [1974 to current] (Appendix 3), , and the Science Citation Index & Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (Web of Science, Thomson) [1945 to current] (Appendix 4).

We identified ongoing studies by searching WHO ICTRP (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) using the following search terms: (Condition = (colorectal cancer OR colon cancer OR colorectal neoplas* OR colon neoplas* OR rectal cancer OR rectal neoplas*) AND Intervention = (cea OR Carcinoembryonic Antigen OR carcinoembryonic antibod*)), and by searching ClinicalTrials (clinicaltrials.gov) using the following search terms: (Condition = (colorectal cancer OR colon cancer OR colorectal neoplas* OR colon neoplas* OR rectal cancer OR rectal neoplas*) AND Intervention = (cea OR Carcinoembryonic Antigen OR carcinoembryonic antibod*)).

We conducted an additional search of the ASCO meeting library (meetinglibrary.asco.org/) for conference abstracts using the following search terms: (Title word search: “cea OR "carcinoembryonic antigen" OR "carcinoembryonic antigen").

Searching other resources

Following the search of bibliographic databases, we checked reference lists of retrieved reviews and all included studies. In addition, we performed a 'Related articles' search on PubMed on all included studies.

In the protocol, we stated we would contact the principal investigators of all included studies to identify further relevant literature, clarify methodological queries if they exist and to ask for any unpublished data relevant to this review. Unfortunately, due to time constraints and the large number of studies included in our review, we were not able to do this.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

To identify relevant studies, two review authors (BDN and IP) scanned all titles and excluded those studies clearly not relevant to the topic of CEA for the detection of CRC recurrence. Following this, the same two review authors (BDN, IP) independently assessed both the titles and abstracts of the selected studies and retrieved the full‐text articles for those deemed to be relevant and for those where a decision could not be made on the basis of the title and abstract alone.

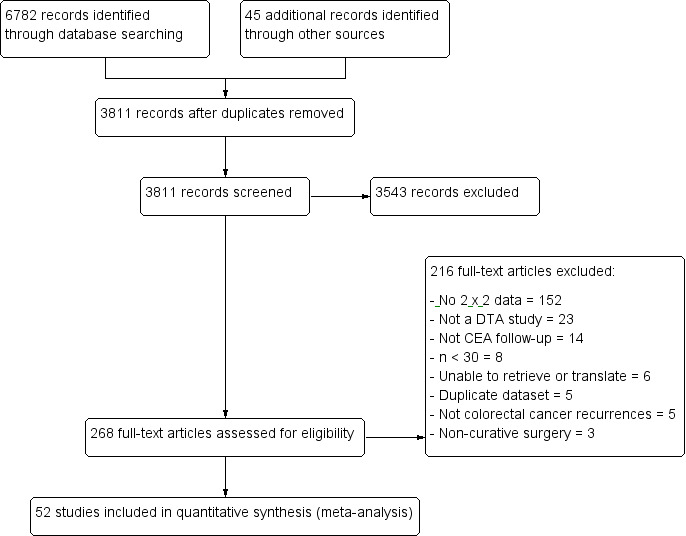

We assessed the remaining full‐text articles to see whether 2 x 2 accuracy data were available and, if so, we included the study in the review and implemented a full data extraction. Reasons for exclusions are detailed in Figure 1. A third review author (BS) resolved any disputes over which references should be included.

Data extraction and management

Full data extraction was guided by a background information sheet describing how each item should be interpreted. Two review authors piloted and refined this form, using three initial studies. A third review author resolved any disagreements over extracted data.

We extracted data into an Excel spreadsheet under the following headings: author, year, title, country, study design, setting, dates of data collection, population (n), inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, included participants (n), age, smoking status, site of primary tumour, stage/grade of primary tumour, investigations done to ensure no residual disease, chemotherapy/radiotherapy, follow‐up schedule, cases of recurrence (n), CEA timing, CEA technique, CEA threshold, reference standard, timing of CEA versus reference standard, true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), false negatives (FN), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), AUC, QUADAS‐2 items (including CEA laboratory technique, Appendix 5).

In the protocol we stated we would contact authors if data were not available, but due to time constraints we were not able to do this.

Assessment of methodological quality

Assessment of methodological quality

QUADAS‐2 is a generic set of criteria for assessing the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies. It consists of four key domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and the flow of patients through the study and timing of the index test in relation to the reference standard. Signalling questions are provided to guide judgement of the risk of bias across these four domains (Whiting 2011).

We modified QUADAS‐2 to exclude items not applicable to this review. A guide to the operational definitions for the modified QUADAS‐2 items can be found in Appendix 5.

We included additional questions regarding index test repetition (4.A.1) and CEA laboratory technique (2.A.2 to 2.A.4). We modified "Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard?" (Yes/No/Unclear) to instead read "4.A.2. Was the timing between index test(s) and reference standard ascertainable?" (Yes/Unclear). We also modified "Did all patients receive a reference standard?" to instead read "Did all included patients who had at least one CEA measurement receive a reference standard?". We removed "Was a case‐control design avoided?" from the original QUADAS‐2 template as we excluded all case‐control studies. We also removed "Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard?" as knowledge of the reference test result would not bias the interpretation of a positive or negative CEA result, as CEA is an objective test using a predetermined dichotomous threshold.

For the index test domain, items were weighted so that the use of a prespecified threshold and a consistent method for CEA measurement had more influence on the overall judgement than the items regarding estimation of method reproducibility and indication of method accuracy. We made this decision as the latter two items were very rarely reported.

For the reference standard domain, items were weighted so that correctly classifying recurrent CRC had more influence on the overall judgement than whether the reference standard was interpreted without the knowledge of the index test. We made this decision as there were no blinded studies included in the review.

For the flow and timing domain, the five items were weighted so that the inclusion of all patients in the final analysis had the most influence and everyone receiving a reference standard was second most influential. Repetition of the index test prior to the reference standard, ascertainable timing between the index test and reference standard, and to all patients receiving the same reference standard were weighted equally lower.

Signalling questions weighted as high priority determined the overall rating within each domain.

Two review authors (BDN, IP) assessed the quality of all articles independently, discussing any disagreements. Where they could not reach consensus, a third author (BS) acted as moderator. We used the results of the quality assessment for descriptive purposes to provide an evaluation of the overall quality of the included studies and to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

We used descriptive statistics to present summary data for each included study. The Characteristics of included studies tables detail patient sample, study design, CEA technique, follow‐up characteristics and the CEA threshold(s) at which accuracy was reported. We extracted binary diagnostic accuracy data from all included studies as 2 x 2 tables. We present the risk of bias results for each of the four domains of the QUADAS‐2 assessment graphically as described by Whiting 2011.

Inferential statistics were guided by Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy (Macaskill 2010).

We used Review Manager 5 to produce forest plots showing the variability of sensitivity and specificity across primary studies, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals for visual comparison. For studies reporting more than one threshold, we extracted 2 x 2 data for all thresholds. We plotted sensitivity and specificity estimates from each study in ROC space, using the inverse standard error of each estimate to adjust the size of each box to represent precision. For both of these graphs, we included sensitivity and specificity at the threshold closest to 5 µg/L (the most commonly reported threshold). We did not conduct a meta‐analysis across all of the included studies, as we had a sufficient number of studies to carry out meta‐analyses at specific thresholds (see next section), which is clinically more informative.

We used the bivariate model to perform meta‐analysis of sensitivity and specificity (Reitsma 2005). We conducted analyses using the xtmelogit command in Stata (Takwoingi 2013).

We estimated the absolute numbers of false alarms (false positives) and missed cases (false negatives) per 1000 patients tested for each three‐monthly testing interval by applying the pooled sensitivity and specificity derived from this review to: 1) the observed median reported prevalence of recurrence divided by 15 (national guidance is to conduct 14 to 15 CEA tests during follow‐up); 2) the incidence of recurrence data per follow‐up period reported by Sargent 2007 (as in reality the proportion developing recurrence between tests is not constant but falls over time).

Investigations of heterogeneity

Based on the results of the quality assessment, we determined the following most likely sources of heterogeneity: effect of CEA threshold, whether a single CEA measurement or serial measurements were evaluated, and the laboratory techniques employed.

For each subgroup analysis, we conducted bivariate meta‐analyses (Reitsma 2005), using the xtmelogit command in Stata to produce pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity. Summary ROC plots and forest plots are reported to provide a basic picture of between‐study variability in these accuracy estimates.

CEA Threshold

For tests producing a continuous outcome, the threshold at which a positive result is defined directly impacts on the accuracy of the test. The use of different thresholds between studies is therefore a key source of heterogeneity.

We investigated the effect of threshold by carrying out subgroup meta‐analyses for thresholds where sufficient data were available. As some studies reported 2 x 2 data for more than one threshold, this analysis allowed us to include all of the available data. We used Review Manager 5 to produce a forest plot showing the variability of sensitivity and specificity across primary studies at specific thresholds.

Although the original plan was to apply a meta‐analysis method incorporating more than one 2 x 2 table from a single study (Hamza 2009), this method requires data to be reported at consistent thresholds across all included studies, and this was not the case in our review.

Timing of CEA Measurement

Despite sequential CEA measurements being taken in the majority of studies, 2 x 2 data were not reported for each scheduled measurement in any of these studies.

Some studies provided 2 x 2 data for the CEA measurement taken closest to the time point at which recurrence was detected or, for patients who did not experience recurrence, their final follow‐up measurement. Others looked across all of the measurements available for each individual to assess whether any of the sequential measurements had crossed the threshold during the entire follow‐up period. This approach meant the time interval between a rise in CEA and confirmed recurrence was variable across individuals within the same study, but this interval was not reported in any study. Consequently, we classified a patient without confirmed recurrence during the follow‐up period and at least one measurement above the threshold as a false positive in the 2 x 2 table, and a patient with confirmed recurrence but without any CEA rise above the threshold as a false negative.

As this information was not consistently reported in all studies, we could not include this variable in the metaregression analysis. Instead, we explored whether this had a significant impact on accuracy by carrying out a subgroup analysis on those studies that did provide this information. This analysis was also limited to studies reporting accuracy at 5 µg/L (the most commonly reported threshold) to avoid any threshold effects.

Laboratory Technique

The intention was to carry out subgroup analyses on studies using the same laboratory technique in order to assess the effect of technique on accuracy. However, given that so few studies provided sufficient detail regarding the laboratory technique employed, this was not possible. We were interested in exploring whether the implementation of IRP 73/601 reduced between‐study variability in sensitivity and specificity. We therefore used the information provided in each study to assess whether laboratory methods predated the introduction of IRP (e.g. manual Radioimmunoassay (RIA) and Immunoradiometric assay (IRMA) methods) and whether the samples were analysed pre‐1992. We then carried out a subgroup analysis and compared the widths of the 95% confidence intervals for the pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity. We again limited this analysis to those studies reporting accuracy at 5 µg/L to avoid threshold effects.

Sensitivity analyses

To explore whether study quality biased the sensitivity and specificity of CEA, we planned a subgroup analysis to include those studies which had a low risk of bias across all four domains. We also carried out a metaregression analysis using the 'Metadas' macro in SAS, including all of the four domains as ordinal covariates (low risk, unclear, high risk).

Assessment of reporting bias

As described in the protocol and by Van Roon 2011, investigation of publication bias in DTA studies is known to be problematic, and so we have not included assessment of reporting bias in this review (Deeks 2005; Leeflang 2008; Song 2002).

Results

Results of the search

Figure 1 summarises the studies that we identified, screened and selected for this review. Our search resulted in 6782 hits, including 6571 primary studies, 128 reviews, 46 conference abstracts, and 37 registered trials. We identified 45 additional articles by checking the reference lists of retrieved reviews and by performing a 'Related articles' search in PubMed. We removed duplicates (n = 3016), leaving 3811 records for title and abstract screening. Of these, we requested 268 full‐text articles for review, of which we excluded 216 (see Figure 1 for reasons for exclusion). Fifty‐two studies met our inclusion criteria and are included in the final review.

1.

PRISMA flow diagram: results of the search for studies evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of blood CEA to detect recurrent colorectal cancer in patients following curative resection.

Included studies

Prevalence

Included studies were published between 1974 and 2014 and were conducted across 22 countries. All studies were conducted in secondary care, except one Norweigian prospective study (Johnson 1985) in which follow‐up was conducted in both primary and secondary care. In total, 9717 patients were included, and 2951 recurrences detected. The median number of participants in the studies was 139 (interquartile range (IQR): 72 to 247) and the proportion of recurrences detected ranged from 13.5% (Fezoulidis 1987) to 72.3% (Ochoa‐Figueroa 2012) (median: 29.5%, IQR: 24.3 to 36.3%).

Study Design

In 24 studies (46%) a prospective design was used, three of which were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (McCall 1994; Ohlsson 1995; Steele 1982). One study prospectively followed up a cohort of patients of whom some were identified retrospectively (Tate 1982), while another sampled retrospectively from a prospective cohort (Korner 2007). The remaining 26 studies (50%) used a retrospective design.

Clincal features of included patients

Location of recurrence

The location of recurrence was reported in 25 studies (48%) including local, locoregional, and distant recurrence. However, the description of CRC recurrence was heterogeneous and all studies lacked 2 x 2 tables for the diagnostic accuracy of CEA to detect recurrence at each location (Characteristics of included studies).

Staging of primary colorectal cancer

Apart from the two studies (4%) which included only patients with rectal cancer (Barillari 1992; Fezoulidis 1987), the majority of studies (n = 50, 96%) included patients with both colon and rectal cancer.

Thirty‐three studies (63%) used the Dukes staging to describe the primary CRC. A further 11 studies (21%) used the TNM grading system and one study (2%) used the Astler‐Coller staging. The staging was unclear or not reported in the remaining seven studies (13%) (Carlsson 1983; Kohler 1980; Koizumi 1992; Li Destri 1998; Mittal 2011; Ochoa‐Figueroa 2012; Wood 1980).

Of those using Dukes staging, seven included Dukes A ‐ D (Banaszkiewicz 2011; Carpelan‐Holmström 2004; Jubert 1978; Mach 1978; Mariani 1980; Seregni 1992; Yu 1992); 15 included Dukes A ‐ C (Barillari 1992; Deveney 1984; Farinon 1980; Fezoulidis 1987; Fucini 1987; Graffner 1985; Hine 1984; Irvine 2007; Kato 1980; Korner 2007; Luporini 1979; Mackay 1974; McCall 1994; Ohlsson 1995; Triboulet 1983); three used Dukes B ‐ C (Beart 1981; Steele 1982; Wang 1994); two used Dukes C (Hara 2008; Tobaruela 1997); one used Dukes A ‐ C plus palliative cases (Johnson 1985); one used Dukes A ‐ C plus unknown cases (Tate 1982); and four used Dukes A ‐ D plus unknown cases (Bjerkeset 1988; Engarås 2003; Miles 1995; Minton 1985).

Of the 11 studies using the TNM grading system: five included TNM I ‐ III (Kanellos 2006a; Ohtsuka 2008; Park 2009; Tang 2009; Yakabe 2010); four used TNM I ‐ IV (Carriquiry 1999; Nishida 1988; Peng 2013; Staib 2000); and one included TNM II ‐ III (Kim 2013). Only one study reported 2 x 2 tables by stage, reporting on TNM II and TNM III (Hara 2010).

The study that used Astler‐Coller staging included A ‐ C2 (Lucha 1997).

Smokers

Three studies explicitly excluded smokers (Kanellos 2006a; Mariani 1980; Staib 2000), four studies explicitly included some smokers (but there was no way of identifying these patients in the 2 x 2 tables), and the remaining studies did not report smoking status. In the two studies which gave precise figures for smoking prevalence, it was low at 2% smokers (Fucini 1987) and 9% heavy smokers (Mach 1978).

Investigations for residual disease

In 43 studies (83%) it was not clear which (if any) perioperative investigations were done to ensure there was no residual disease before entering follow‐up. In the nine studies that reported this information, three reported using a persistent postoperative elevation of CEA as evidence of residual disease (Hara 2008; Irvine 2007; Steele 1982); one used "signs" of malignancy at the first follow‐up examination (Tate 1982); one used preoperative colonoscopy to resect any lesions outside the section of bowel planned for resection (Banaszkiewicz 2011); one reported using the intraoperative detection of gross residual disease (Lucha 1997); one specified no gross residual disease and clear resection margins (Bjerkeset 1988); one used preoperative abdominal CT and interoperative palpation to exclude liver metastases (Kanellos 2006a); and one reported using preoperative barium enema (BE), chest x‐ray (CXR), liver function tests (LFTs) and CEA, and postoperative BE and colonoscopy to ensure there was no residual disease (Ohlsson 1995).

Treatment

In 14 studies (27%) some (but not all) patients received chemotherapy, and in no studies was a subgroup analysis performed comparing the diagnostic accuracy of CEA in those receiving chemotherapy compared to those who did not (Characteristics of included studies).

Reference standard

In 38 studies (73%) a composite reference standard was used, the composition of which varied greatly between studies (see Characteristics of included studies). In 12 of these, a predefined multimodal follow‐up schedule was used for each patient (although the composition of these varied across studies) (Banaszkiewicz 2011; Carlsson 1983; Fucini 1987; Hara 2008; Irvine 2007; Jubert 1978; Kanellos 2006a; McCall 1994; Ohlsson 1995; Park 2009; Peng 2013; Steele 1982). In 26 studies (50%) a predefined composite follow‐up schedule was used to trigger further investigations for suspected recurrence.

A single investigation was used in three studies (6%) (Mittal 2011; Ochoa‐Figueroa 2012; Staib 2000), of which one reported 2 x 2 tables separately for PET and for CT (Ochoa‐Figueroa 2012).

In the remaining 11 studies (21%), it was unclear what was used as a reference standard.

CEA measurement

The use of predefined follow‐up schedules resulted in multiple CEA measurements being available for analysis.

Eight studies (15%) reported the accuracy of the CEA measurement closest to the time at which recurrence was detected by the reference standard, whilst nine studies (17%) defined CEA as positive if any CEA measurement crossed the threshold at any time within the follow‐up period. In a subset of studies, the authors stated clearly that a single 'positive' measurement would be followed up by a repeat test to confirm the result.

For the remaining 35 studies (67%), it was impossible to unpick which CEA value had been used, due to limited reporting.

Reporting units

CEA studies have used both ng/mL and µg/L in their publications. Numerically these are the same value and for consistency we have used µg/L throughout the review.

Laboratory technique

Details regarding laboratory methods for CEA analysis were inconsistently reported across the included studies. Based on the available information relating to laboratory technique, we were able to able to group the studies as follows:

Twenty‐two studies (42%) analysed samples before the introduction of the international reference preparation (IRP) using manual RIA and IRMA methods;

Seven studies (13%) used an identifiable laboratory technique following introduction of IRP;

Eight studies (15%) used unfamiliar laboratory techniques after the introduction of IRP;

Fifteen studies (29%) did not report laboratory technique.

For the seven studies reporting an identifiable laboratory technique following IRP introduction, six distinct techniques were used: Autodelfia post‐year 2000 (Carpelan‐Holmström 2004; Engarås 2003); Abbott automated instrumentation (Korner 2007); Bayer Immuno 1 (Irvine 2007); Siemens ADVIA centaur (Kim 2013); Roche elecsys (Mittal 2011); and Diasorin/byk santec liaison (Staib 2000). Across these, four thresholds were reported: 3 µg/L (Staib 2000); 5 µg/L (Carpelan‐Holmström 2004; Kim 2013; Mittal 2011); 5.6 µg/L (Engarås 2003); and 10 µg/L (Irvine 2007; Korner 2007).

Forty‐three studies (83%) did not report an estimation of CEA method reproducibility nor an indication of method accuracy. Of the remaining nine studies, three (6%) reported both an estimation of reproducibility and an indication of method accuracy (Carpelan‐Holmström 2004; Engarås 2003; Steele 1982), four (8%) clearly reported only an estimation of reproducibility (Fucini 1987; Hine 1984; Mach 1978; Mackay 1974), and the remaining two (4%) reported only the indication of method accuracy (Irvine 2007; Miles 1995).

Excluded studies

Of the 216 excluded full‐text articles (Figure 1; Characteristics of excluded studies):

152 studies (70%) did not report complete 2 x 2 data, and 74 (34%) reported no 2 x 2 data at all: 59 (27%) only reported recurrences; 16 (7%) only reported CEA positive cases; and three (1%) only CEA negative);

23 studies (11%) did not conduct a single‐point diagnostic test accuracy study (14 (6%) used alternative analyses (trend, nomogram, slope, or median CEA); five were case‐control studies (2%); three (1%) were review articles; and one was an economic analysis);

14 studies (6%) did not report an analysis of serum CEA measurements taken as part of a follow‐up schedule (seven (5%) reported preoperative CEA measurements; six (3%) reported the prognostic value of one postoperative CEA measurement; and one used intraoperative portal vein sampling);

eight studies (4%) included fewer than 30 patients;

six studies were unavailable or needed translation (five studies (2%) were not retrieved after worldwide search by the British Library, and we were not able to translate the remaining study);

five studies (2%) did not clearly report colorectal cancer recurrence (three (1%) reported on only liver metastases; and two (1%) reported colorectal cancer recurrence together with other cancer types);

five studies (2%) reported datasets already included in the review;

three studies (1%) reported non‐curative surgery.

We have not included two large RCTs in the review: the FACS trial (as 2 x 2 data were not reported in the published paper (Primrose 2014)), and the CEASL trial, which was published following our search and did not report on negative CEA cases (Treasure 2014).

Methodological quality of included studies

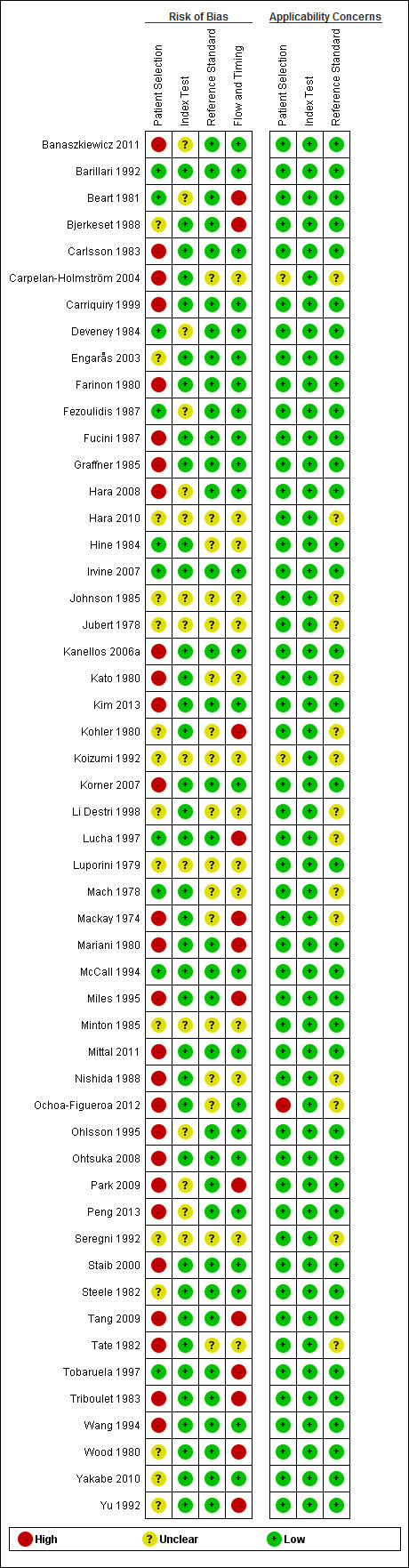

We assessed all 52 studies using the QUADAS‐2 framework. Figure 2 shows the summary of overall risk of bias and applicability concerns, and Figure 3 presents the risk of bias and applicability concerns as overall percentages.

2.

QUADAS‐2 risk of bias and applicability concerns summary including review authors' judgements about each domain for each included study

3.

QUADAS‐2 risk of bias and applicability concerns graph including review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies

Three studies (6%), including 516 participants of whom 177 experienced recurrence, were assessed as being at low risk of bias and low concern regarding applicability across all domains (Barillari 1992; Irvine 2007; McCall 1994). Across these studies, each reported a different threshold (3, 10, and 5 µg/L respectively) using CEA test kits from three different manufacturers (with poor description of method accuracy). Each study applied a different but "appropriate" follow‐up schedule to detect recurrence. Consequently, the planned subgroup analysis of high‐quality studies (low risk of bias in all four domains) was not feasible.

Risk of bias

We judged 34 studies (65%) to be at high risk of bias in at least one of the four domains (Figure 3).

For the patient selection domain, items were weighted so that the presence of inappropriate exclusions had more influence on the overall judgement than the presence of a consecutive or random sample. Of the 27 studies judged to be at high risk of bias for patient selection (52%), inappropriate exclusions were based on:

advanced age (Carlsson 1983; Graffner 1985; Korner 2007; Ohlsson 1995);

previous malignancy (Ohtsuka 2008);

poor prognosis for further surgery (Banaszkiewicz 2011; Ohlsson 1995);

preoperative CEA values (Carpelan‐Holmström 2004; Carriquiry 1999; Farinon 1980; Miles 1995; Tang 2009; Wang 1994);

temporary rises in CEA (Mackay 1974);

non‐rising CEA (Mittal 2011);

using a minimum follow‐up period (Carriquiry 1999; Kim 2013; Korner 2007; Mackay 1974);

'incomplete' follow‐up measurements (Carpelan‐Holmström 2004; Carriquiry 1999; Hara 2008; Kato 1980; Korner 2007; Nishida 1988);

factors related to other follow‐up tests (Fucini 1987; Peng 2013; Tang 2009; Triboulet 1983);

early signs of malignancy or death (Carlsson 1983; Tate 1982);

smoking status (Kanellos 2006a; Mariani 1980);

concomitant benign disease or recent surgery (Kanellos 2006a; Mariani 1980; Park 2009; Peng 2013; Staib 2000);

patients not presenting a “diagnostic problem” (Staib 2000).

There were no studies deemed to be at high risk of bias based on the judgements made about the index test.

There were no studies at high risk of bias based on the judgements made about the reference standard, and in 17 (33%) the risk was unclear.

Thirteen studies (25%) were deemed to be at high risk of bias based on flow and timing. In four studies, not all patients were included in the final analysis (Beart 1981; Bjerkeset 1988; Kohler 1980; Park 2009). In the remaining nine studies, a raised CEA value triggered the reference standard which could introduce work‐up bias and result in false negative CEA results being misclassified as true negative results (Lucha 1997; Mackay 1974; Mariani 1980; Miles 1995; Tang 2009; Tobaruela 1997; Triboulet 1983; Wood 1980; Yu 1992).

Applicability concerns

We judged 37 studies (71%) to be at low risk of applicability concerns in all three domains (Figure 3). We rated only one study (Ochoa‐Figueroa 2012) at high risk of applicability concerns in relation to patient selection, as it did not include all patients undergoing postoperative follow‐up, but only those referred with suspected recurrence to the Department of Nuclear Medicine for fluoro‐deoxy‐glucose (FDG) PET‐CT. There were no studies deemed to be at high risk for applicability based on the index test or reference standard.

Unclear risk

Of the 364 domains, we deemed 85 (23%) to be at unclear risk of bias or applicability. For the vast majority of these items poor reporting accounted for the unclear rating.

Findings

Diagnostic accuracy

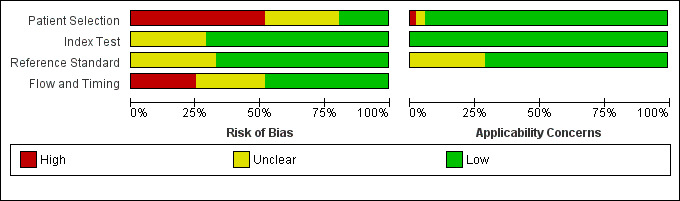

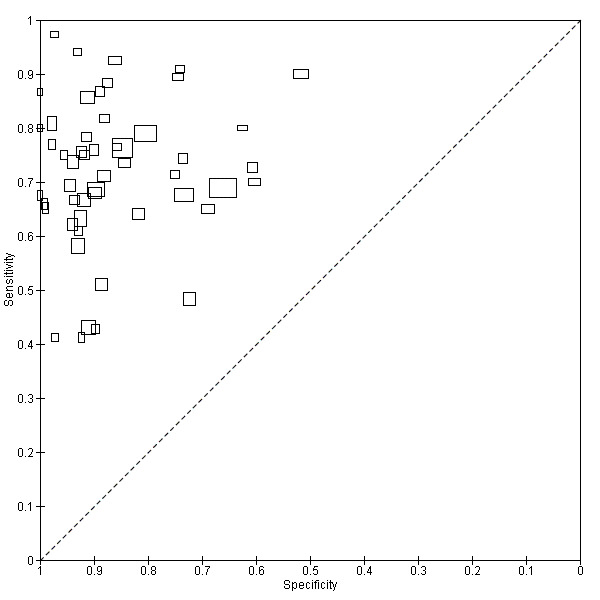

The forest plot in Figure 4 (Analysis 1) shows the range of sensitivity and specificity of CEA for the detection of recurrent colorectal cancer across all 52 included studies.

4.

Forest plot for all 52 included studies for the threshold reported closest to 5 µg/L

TP = true positive; FP = false positive; FN = false negative; TN = true negative

The blue square depicts the sensitivity and specificity for each study and the horizontal line represents the corresponding 95% confidence interval for these estimates.

For studies reporting accuracy at more than one threshold, 2 x 2 data at the threshold closest to 5 μg/L are included in the plot (5 μg/L was the most commonly reported threshold).

.Sensitivity ranged from 41% to 97% and specificity from 52% to 100%.

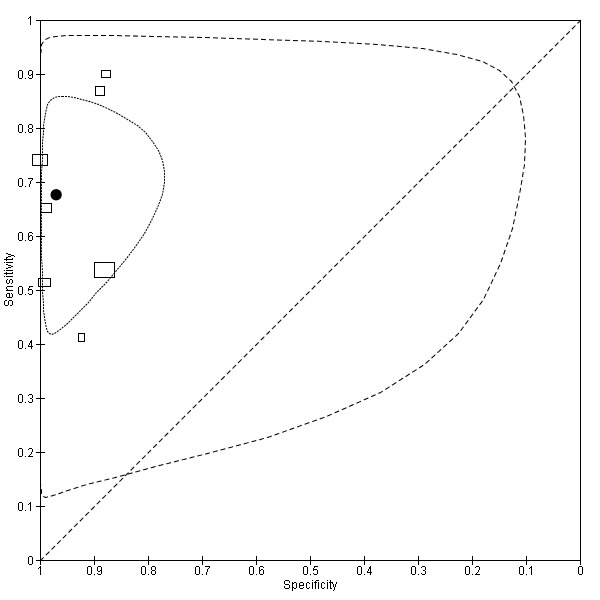

Figure 5 plots each of the 52 studies in ROC space. The size of each box is proportional to the inverse standard error for sensitivity and specificity for each study (a larger box indicates greater precision).

5.

Scatter plot of sensitivity versus specificity for all 52 studies, regardless of threshold.

Each box represents the 2 x 2 data extracted from each study, with the width of the boxes being proportional to the inverse standard error of the specificity and the height of the boxes proportional to the inverse standard error of the sensitivity.

Effect of CEA threshold on diagnostic accuracy

Forty‐one studies (79%) reported accuracy at just a single threshold. A wide range of thresholds were reported (2 to 40 µg/L). Four studies (8%) did not report which threshold they used (Graffner 1985; Johnson 1985; Ohlsson 1995; Seregni 1992).Seven studies (13%) reported 2 x 2 data for more than one threshold:

Banaszkiewicz 2011: 5 and 10 µg/L

Bjerkeset 1988: 3.5 and 5 µg/L

Carlsson 1983: 3 and 7.5 µg/L

Korner 2007: 4 and 10 µg/L

Mittal 2011: 3, 5, 10, 20, and 50 µg/L

Steele 1982: 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 µg/L

Wood 1980: 25 and 40 µg/L

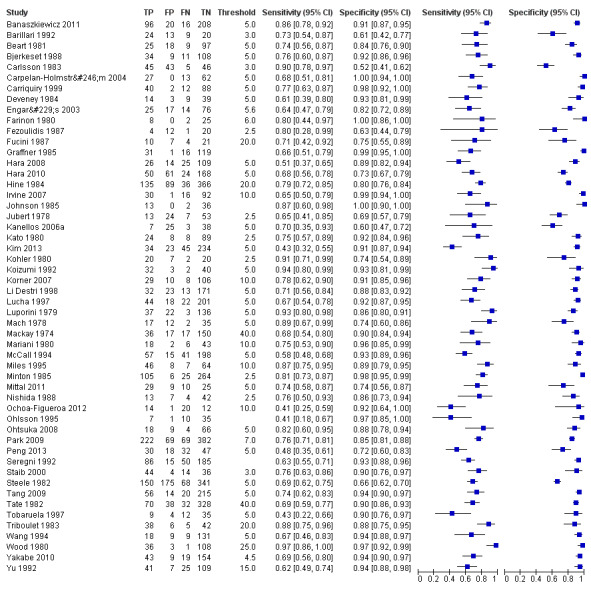

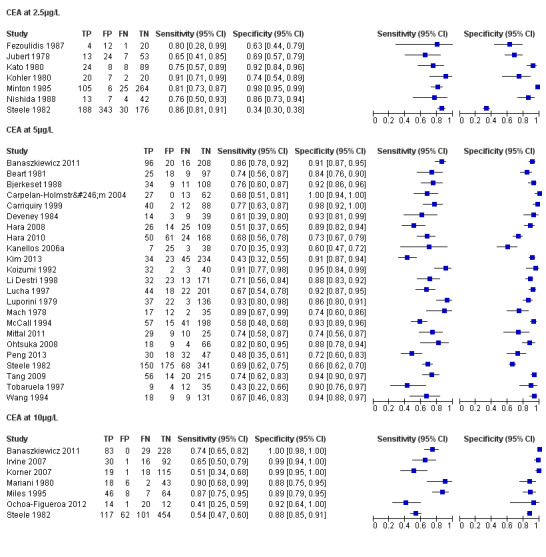

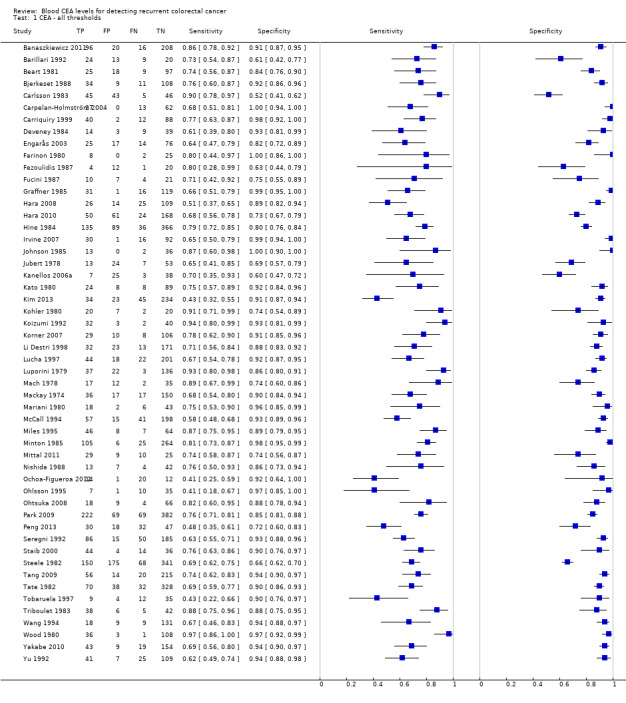

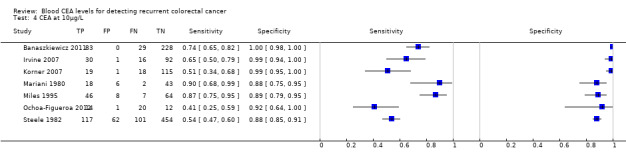

The forest plots in Figure 6 (Analysis 2) show the range of sensitivity and specificity for studies reporting the accuracy of CEA at cut‐off values of 2.5, 5 and 10 µg/L.

6.

Forest plot broken down by threshold: CEA at 2.5µg/L, CEA at 5µg/L, CEA at 10µg/L.

TP = true positive; FP = false positive; FN = false negative; TN = true negative

The blue square depicts the sensitivity and specificity for each study and the horizontal line represents the corresponding 95% confidence intervals for these estimates.

The summary ROC curves and the summary estimates including confidence ellipses for the threshold values of 2.5, 5, and 10 µg/L (Analyses 3, 4 and 5) can be found in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 respectively.

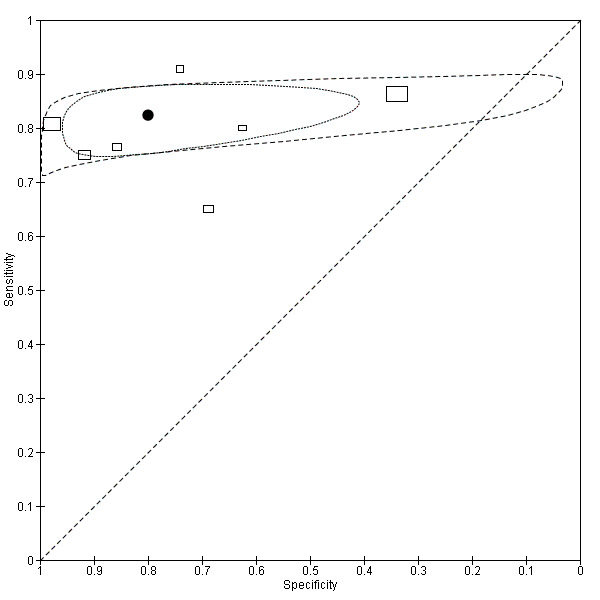

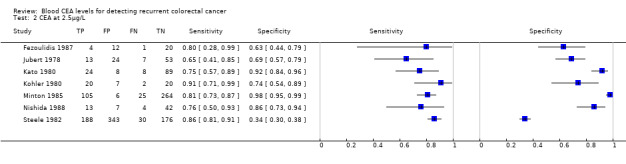

7.

Summary ROC plot of accuracy at a threshold of 2.5 µg/L.

Each box represents the 2 x 2 data extracted from each study. The width of the box is proportional to the number of patients who did not experience recurrence in each study, and the height is proportional to the number of patients that did develop recurrent CRC.

The filled circle is the pooled estimate for sensitivity and specificity and the line running through it is the summary ROC curve.

The smaller dotted ellipse represents the 95% credible region around the summary estimate; the larger dashed ellipse represents the 95% prediction region.

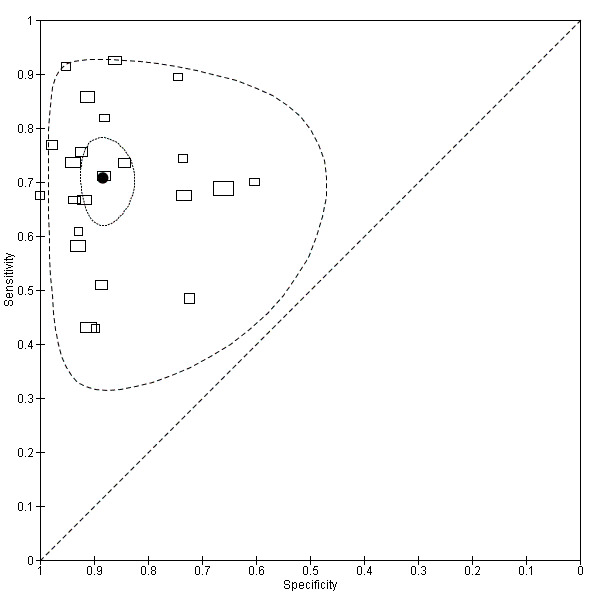

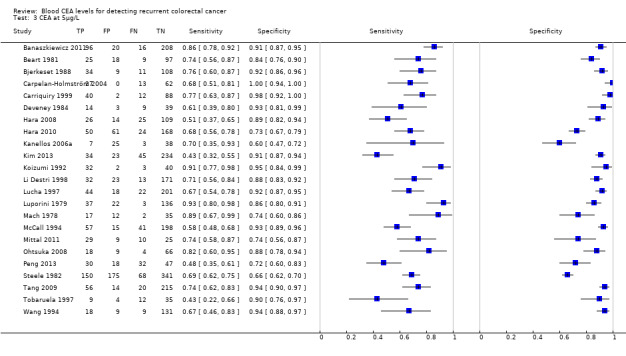

8.

Summary ROC plot of accuracy at a threshold of 5 µg/L.

Each box represents the 2 x 2 data extracted from each study.

The width of the box is proportional to the number of patients who did not experience recurrence in each study, and the height is proportional to the number of patients that did develop recurrent CRC.

The filled circle is the pooled estimate for sensitivity and specificity and the line running through it is the summary ROC curve.

The smaller dotted ellipse represents the 95% credible region around the summary estimate; the larger dashed ellipse represents the 95% prediction region.

9.

Summary ROC plot of accuracy at a threshold of 10 µg/L.

Each box represents the 2 x 2 data extracted from each study.

The width of the box is proportional to the number of patients who did not experience recurrence in each study, and the height is proportional to the number of patients that did develop recurrent CRC.

The filled circle is the pooled estimate for sensitivity and specificity and the line running through it is the summary ROC curve.

The smaller dotted ellipse represents the 95% credible region around the summary estimate; the larger dashed ellipse represents the 95% prediction region.

In the seven studies reporting a threshold of 2.5 µg/L, the sensitivity ranged from 65% to 91% and specificity from 34% to 98%. The pooled sensitivity of these studies was 82% (95% CI 78% to 86%) and pooled specificity 80% (95% CI 59% to 92%). Assuming that the proportion of patients with recurrence in any single testing period is 2% (based on our observed prevalence of recurrence of 30% and national guidance to conduct 14 to 15 CEA tests during follow‐up), for every 1000 patients tested at a threshold of 2.5 µg/L, 16 cases of recurrence will be detected, four cases will be missed, and there will be 196 false alarms (people referred unnecessarily for further testing). More precise estimates of test performance using the incidence data reported by Sargent 2007 can be found in Table 2.

Summary of findings 2. Outcome of follow‐up testing using a CEA threshold of 2.5 µg/L.

| Month when CEA measured | per 1000 patients tested at a threshold of 2.5 µg/L | False alarm rate | ||||

| Estimated recurrences¹ | Referrals for raised CEA | Cases of recurrence detected | Cases of recurrence missed | False alarms (cases investigated when cancer not present) | ||

| Follow‐up years 1 and 2: 3‐monthly CEA testing | ||||||

| 3 | 19 | 212 | 16 | 3 | 196 | 92% |

| 6 | 19 | 212 | 16 | 3 | 196 | 92% |

| 9 | 39 | 224 | 32 | 7 | 192 | 86% |

| 12 | 39 | 224 | 32 | 7 | 192 | 86% |

| 15 | 37 | 223 | 30 | 7 | 193 | 87% |

| 18 | 37 | 223 | 30 | 7 | 193 | 87% |

| 21 | 31 | 219 | 25 | 6 | 194 | 89% |

| 24 | 31 | 219 | 25 | 6 | 194 | 89% |

| Follow‐up years 3, 4 and 5: 6‐monthly CEA testing | ||||||

| 30 | 46 | 229 | 38 | 8 | 191 | 83% |

| 36 | 36 | 223 | 30 | 6 | 193 | 87% |

| 42 | 27 | 217 | 22 | 5 | 195 | 90% |

| 48 | 25 | 216 | 21 | 4 | 195 | 90% |

| 54 | 17 | 211 | 14 | 3 | 197 | 93% |

| 60 | 14 | 208 | 11 | 3 | 197 | 95% |

1Estimates are based on data reported by Sargent 2007. Three‐monthly data were unavailable, and so constant rates were assumed during each six‐month period for the first two years. Estimates are rounded.

In the 23 studies which reported the impact of applying a threshold of 5 µg/L, sensitivity ranged from 43% to 93% and specificity from 60% to 100%. The pooled sensitivity of these studies was 71% (95% CI 64% to 76%) and pooled specificity 88% (95% CI 84% to 92%). For every 1000 patients tested at a threshold of 5 µg/L, 14 cases of recurrence will be detected, six cases will be missed, and there will be 118 false alarms. More precise estimates of test performance using the incidence data reported by Sargent 2007 can be found in Table 3

Summary of findings 3. Outcome of follow‐up testing using a CEA threshold of 5 µg/L.

| Month when CEA measured | per 1000 patients tested at a threshold of 5 µg/L | False alarm rate | ||||

| Estimated recurrences¹ | Referrals for raised CEA | Cases of recurrence detected | Cases of recurrence missed | False alarms (cases investigated when cancer not present) | ||

| Follow‐up years 1 and 2: 3‐monthly CEA testing | ||||||

| 3 | 19 | 131 | 13 | 6 | 118 | 90% |

| 6 | 19 | 131 | 13 | 6 | 118 | 90% |

| 9 | 39 | 143 | 28 | 11 | 115 | 80% |

| 12 | 39 | 143 | 28 | 11 | 115 | 80% |

| 15 | 37 | 142 | 26 | 11 | 116 | 82% |

| 18 | 37 | 142 | 26 | 11 | 116 | 82% |

| 21 | 31 | 138 | 22 | 9 | 116 | 84% |

| 24 | 31 | 138 | 22 | 9 | 116 | 84% |

| Follow‐up years 3, 4 and 5: 6‐ monthly CEA testing | ||||||

| 30 | 46 | 147 | 33 | 13 | 114 | 78% |

| 36 | 36 | 142 | 26 | 10 | 116 | 82% |

| 42 | 27 | 136 | 19 | 8 | 117 | 86% |

| 48 | 25 | 135 | 18 | 7 | 117 | 87% |

| 54 | 17 | 130 | 12 | 5 | 118 | 91% |

| 60 | 14 | 128 | 10 | 4 | 118 | 92% |

1Estimates are based on data reported by Sargent 2007. Three‐monthly data were unavailable, and so constant rates were assumed during each six‐month period for the first two years. Estimates are rounded.

In the seven studies reporting the impact of applying a threshold of 10 µg/L, sensitivity ranged from 41% to 87% and specificity from 88% to 100%. The pooled sensitivity of these studies was 68% (95% CI 53% to 79%) and pooled specificity 97% (95% CI 90% to 99%). For every 1000 patients tested at a threshold of 10 µg/L, 14 cases of recurrence will be detected, seven cases will be missed, and there will be 29 false alarms. More precise estimates of test performance using the incidence data reported by Sargent 2007 can be found in Table 4.

Summary of findings 4. Outcome of follow‐up testing using a CEA threshold of 10 µg/L.

| Month when CEA measured | per 1000 patients tested at a threshold of 10 µg/L | False alarm rate | ||||

| Estimated recurrences¹ | Referrals for raised CEA | Cases of recurrence detected | Cases of recurrence missed | False alarms (cases investigated when cancer not present) | ||

| Follow‐up years 1 and 2: 3‐ monthly CEA testing | ||||||

| 3 | 19 | 42 | 13 | 6 | 30 | 70% |

| 6 | 19 | 42 | 13 | 6 | 29 | 70% |

| 9 | 39 | 55 | 27 | 13 | 29 | 52% |

| 12 | 39 | 55 | 27 | 13 | 29 | 52% |

| 15 | 37 | 54 | 25 | 12 | 29 | 53% |

| 18 | 37 | 54 | 25 | 12 | 29 | 53% |

| 21 | 31 | 50 | 21 | 10 | 29 | 58% |

| 24 | 31 | 50 | 21 | 10 | 29 | 58% |

| Follow‐up years 3, 4 and 5: 6‐ monthly CEA testing | ||||||

| 30 | 46 | 60 | 31 | 15 | 29 | 48% |

| 36 | 36 | 53 | 24 | 12 | 29 | 54% |

| 42 | 27 | 48 | 19 | 9 | 29 | 61% |

| 48 | 25 | 46 | 17 | 8 | 29 | 63% |

| 54 | 17 | 41 | 11 | 6 | 30 | 72% |

| 60 | 14 | 39 | 10 | 5 | 30 | 75% |

1Estimates are based on data reported by Sargent 2007. Three‐monthly data were unavailable, and so constant rates were assumed during each six‐month period for the first two years. Estimates are rounded.

Effect of the timing of CEA measurement

As previously described, we used two approaches when choosing which CEA measurement to include in the 2 x 2 tables. The first was to evaluate the CEA measurement taken closest to the time point at which recurrence was detected; the second was to look across all measurements to assess whether any had crossed the threshold during the entire follow‐up period.

Including only those studies reporting accuracy at a threshold of 5 µg/L, we carried out a subgroup analysis for these two strategies.

We adopted the first strategy in eight studies, for which the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 69.0% (95% CI 57.3% to 78.7%) and 90.0% (95% CI 77.8% to 95.9%) respectively. We adopted the second strategy in nine studies, for which the pooled sensitivity and specificity were 64.5% (95% CI 55.2% to 72.9%) and 89.5% (95% CI 83.4% to 93.5%) respectively.

Effect of laboratory technique

We were unable to carry out a subgroup analysis based on specific laboratory techniques, as reporting was so limited that it is was difficult to identify groups of studies where we could be confident that they had all used consistent methods.

For those studies reporting accuracy at a threshold of 5 µg/L, we carried out a subgroup analysis comparing the variability in accuracy before and after the introduction of the international reference preparation (IRP 73/601) calibration. We excluded one study (Li Destri 1998) from this analysis, as there was insufficient information about the timing of the sample analysis and laboratory technique. There were 11 studies predating the introduction of the IRP, providing a pooled sensitivity of 73.6% (95% CI 63.2% to 81.8%) and a pooled specificity of 88.5% (95% CI 83.2% to 92.2%), and 11 studies used methods which incorporated the IRP, resulting in a pooled sensitivity of 67.9% (95% CI 58.6% to 75.9%) and a pooled specificity of 88.6% (95% CI 80.0% to 93.7%). These results indicate no significant reduction in variability, and this was confirmed when we added it as a covariate in the metaregression (P = 0.958).

Effect of patient selection on diagnostic accuracy

When restricting the analyses to the 11 studies deemed to be at low risk of bias in the patient selection domain of the QUADAS‐2 assessment, the sensitivity ranged from 43% to 93% and specificity from 61% to 99%.

We added the patient selection risk of bias item as an ordinal covariate (low risk = 6, unclear risk = 6 and high risk = 11) in the metaregression analysis for those studies reporting accuracy at 5 µg/L. The effect of this covariate was not significant (P = 0.771).

Effect of index test on diagnostic accuracy

There were no studies deemed to be at high risk of bias in the index test domain of the QUADAS‐2 assessment. When restricting the analyses to the 37 studies (71%) deemed to be at low risk of bias in the index test domain of the QUADAS‐2 assessment, the sensitivity ranged from 41% to 97% and specificity from 52% to 100%.

We added the index test risk of bias item as a covariate (low risk = 15, unclear risk = 8) in the metaregression analysis for those studies reporting accuracy at 5 µg/L. The effect of this covariate was not significant (P = 0.901).

Effect of the reference standard on diagnostic accuracy

There were also no studies deemed to be at high risk of bias in the reference standard domain of the QUADAS‐2 assessment. When restricting the analyses to the 35 studies (67%) deemed to be at low risk of bias in the reference standard domain of the QUADAS‐2 assessment, the sensitivity ranged from 41% to 97% and specificity from 52% to 100%.

We added the reference standard risk of bias item as a covariate (low risk = 17, unclear risk = 6) in the metaregression analysis for those studies reporting accuracy at 5 µg/L. The effect of this covariate was not significant (P = 0.292).

Effect of flow and timing on diagnostic accuracy

When restricting the analyses to the 25 studies (48%) deemed to be at low risk of bias in the flow and timing domain of the QUADAS‐2 assessment, the sensitivity ranged from 41% to 95% and specificity from 52% to 100%.

We added the flow and timing risk of bias item as an ordinal covariate (low risk = 12, unclear risk = 6 and high risk = 5) in the metaregression analysis for those studies reporting accuracy at 5 µg/L. The effect of this covariate was not significant (P = 0.664).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We include 52 studies in the meta‐analysis, covering 9717 patients (median sample size = 139, IQR: 72 ‐ 247). The median proportion of recurrences in each study was 29% (IQR: 24% ‐ 36%), agreeing with previously reported recurrence rates (Labianca 2010).

The diagnostic accuracy of CEA was reported at 15 different thresholds, ranging from 2 to 40 µg/L. Seven studies (13%) reported accuracy at a threshold of 2.5 µg/L, providing a pooled sensitivity of 82% (95% CI 78% to 86%) and a pooled specificity of 80% (95% CI 59% to 92%). The most commonly reported threshold was 5 µg/L (23 studies, 44%), providing a lower sensitivity of 71% (95% CI 64% to 76%) and an increased specificity of 88% (95% CI 84% to 92%). Seven studies (13%) reported accuracy at a threshold of 10 µg/L. Implementing such a high threshold reduced sensitivity to 68% (95% CI 53% to 79%), but provided high specificity of 97% (95% CI 90% to 99%).

Reporting quality was insufficient in important areas such as laboratory techniques. Insufficient detail about laboratory techniques and the frequent use of composite reference standards made it impossible to conduct desirable subgroup analyses. An individual‐patient data meta‐analysis would be required to fully explore the influence of factors such as preoperative CEA levels, chemotherapy, site of recurrence and smoking status, that are known to impact on CEA levels in follow‐up.

Our results compared with other reports

Tan 2009 carried out a meta‐analysis of 20 studies that reported the accuracy of CEA for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer recurrence using the Moses‐Littenberg Method (Moses 1993). Their pooled estimate for specificity at a threshold of 5 µg/L was the same as ours (88%). Our pooled estimate for sensitivity was higher (71% versus 63%), but this difference is not statistically significant.

The method used by Tan 2009 to identify 2.2 µg/L as the 'optimum' CEA threshold was based on linear extrapolation (the lowest threshold included in their study was 3 µg/L). We instead implement bivariate meta‐analyses (Reitsma 2005), as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy (Macaskill 2010). This method is statistically more rigorous than the method implemented in Tan 2009, and directly accounts for the within‐ and between‐study variability in sensitivity and specificity.

We question the Tan 2009 recommendation of 2.2 µg/L (which was based on achieving high sensitivity) not just on the basis of the low specificity (and high false alarm rate), but also because there appears to be a 'ceiling' effect in terms of sensitivity ‐ even at a threshold of 2.5 µg/L, around one in five cases of recurrence would be missed. The failure to exceed a sensitivity of about 80% even with a low threshold or poor specificity reflects the well‐documented fact that some recurrent cancers are not associated with a rise in blood CEA levels.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

Completeness

A key strength of this review is the comprehensiveness of our searches. We avoided the use of search filters and did not restrict our review to English‐language publications. Two review authors screened all abstracts independently, with a third independently settling any disagreement over inclusion. We retrieved and analysed all full‐text articles that we felt could be potentially relevant based on the title and abstract. We based additional searches on the citation of full‐text articles to reduce the risk of missing relevant studies. Foreign‐language articles were translated or assessed or both by colleagues of the authors proficient in the language in question.

It is not possible to estimate the impact of unpublished studies on our findings, as little is known about the mechanisms of publication bias for diagnostic accuracy studies (Allen 2013). Despite this, our included studies are likely to represent the vast majority of studies that provide evidence on this topic.

Two review authors then extracted data independently, and three authors independently performed QUADAS‐2 assessment of the included studies, with subsequent discussion to reach consensus on overall judgements of risk of bias and applicability. The meta‐analyses followed Cochrane DTA guidelines.

Variability

A major weakness of this review is that we considered many included studies to be at high risk of bias. There was also considerable between‐study variation in the reporting of: 1) stage of primary disease included; 2) approach to ensuring no residual disease; 3) reporting of smoking; 4) reporting of chemotherapy treatment; and 5) the location of recurrence. All of these factors could plausibly have some influence on CEA levels, but corresponding 2 x 2 tables were not presented for these subgroups, and so it was not possible to adjust for this variation in our analyses.

The QUADAS‐2 assessment of methodological quality highlighted the extent of the quality issues in the existing literature. Even the three studies that we assessed as having no risk of bias or applicability concerns were subject to considerable between‐study heterogeneity: they each reported accuracy at different CEA thresholds, implemented different CEA laboratory techniques, and used differing composite reference standards to detect recurrence. The varying thresholds made it unfeasible to provide pooled diagnostic accuracy estimates for these high‐quality studies.

Over half of the included studies (n = 27, 52%) were at high risk of selection bias, mainly due to inappropriate patient exclusions. We deemed a further 15 studies (29%) to be at unclear risk of bias for patient selection, due to poor reporting. This makes our accuracy estimates susceptible to selection bias, particularly if those excluded were at particularly high or low risk of recurrence. To investigate this further, we removed those studies at high and unclear risk of bias for patient selection in a sensitivity analysis. The pooled estimates were not significantly different from the overall pooled results (sensitivity = 73%, 95% CI 64% to 80%; specificity = 87%, 95% CI 79% to 92%).

The methods used to measure CEA were also poorly reported: three studies (6%) did not report the CEA threshold used to determine a positive result, 15 studies (29%) did not report which laboratory technique had been used, and 43 studies (83%) failed to report any indicator of method accuracy or an estimate of CEA reproducibility. It is well known that variability exists between laboratory methods and between laboratories, and without this information it is impossible to adjust for any bias that has been introduced by the differences in method. The IRP calibration (73/601, introduced in 1992) attempts to reduce between‐laboratory and between‐technique variability, so we performed a sensitivity analysis leaving only the studies that were conducted after its introduction. We did not find the pooled accuracy estimates to be significantly different from the overall analysis (sensitivity = 67.9%, 95% CI 58.6% to 75.9%; specificity = 88.6%, 95% CI 80.0% to 93.7%).

A possible source of bias in this review is likely to be the methods used to implement the reference standard. In nine studies, the reference standard was only carried out if a rise in CEA was detected, possibly causing false‐negative results to be misclassified as true‐negative results. Furthermore, most studies implemented a composite reference standard, but failed to consistently reported which investigation (within the composite) actually diagnosed recurrence. In half of the studies (n = 26, 50%), positive results for certain reference tests triggered the use of other reference tests. These concerns over partial and differential verification were considered in the flow and timing domain of QUADAS‐2, explaining why there were no studies deemed to be at high risk of bias in the reference standard domain.

The time between the CEA measurement and the reference test used in the 2 x 2 table was not reported in any of the studies. There is therefore a high chance of misclassification due to disease progression during the time between CEA and the reference test. Understanding this relationship is important in this setting as: a) a high‐grade recurrence will progress more quickly than low‐grade; b) this information is required to estimate lead time. Furthermore, no study reported 2 x 2 data for each three‐ to six‐month period of follow‐up, which would be desirable given that CRC recurrence is known to occur more commonly in the first two years of follow‐up, suggesting that a variable threshold may have greater accuracy (Sargent 2007).

Applicability of findings to the review question

All of the studies identified were carried out in hospital outpatient clinics, except one that followed up patients in both primary and secondary care. As the patient population is so well defined in this review (postoperative curative colorectal cancer resection), it is unlikely that the actual clinical setting in which follow‐up takes place would have any influence on the severity of disease seen or consequently on the accuracy of CEA.

Changing the setting of follow‐up could affect the accuracy of the CEA measurement if transporting blood samples taken in a community setting are stored suboptimally and there are long delays in blood reaching the laboratory. But monitoring CEA in primary care is already common practice in many countries and these potential problems have been successfully addressed. Implementation of the reference standard might also vary if patients being followed up in hospital are more likely to be referred for further investigation for reasons other than a rise in CEA. However, the Australian multicentre RCT investigating GP versus surgical follow‐up reported similar recurrence rates and times to detection, irrespective of place of follow‐up (Wattchow 2006).